Knowledge Deficit About How Chemotherapy Affects Long-Term Survival in Testicular Tumor Patients

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Collective

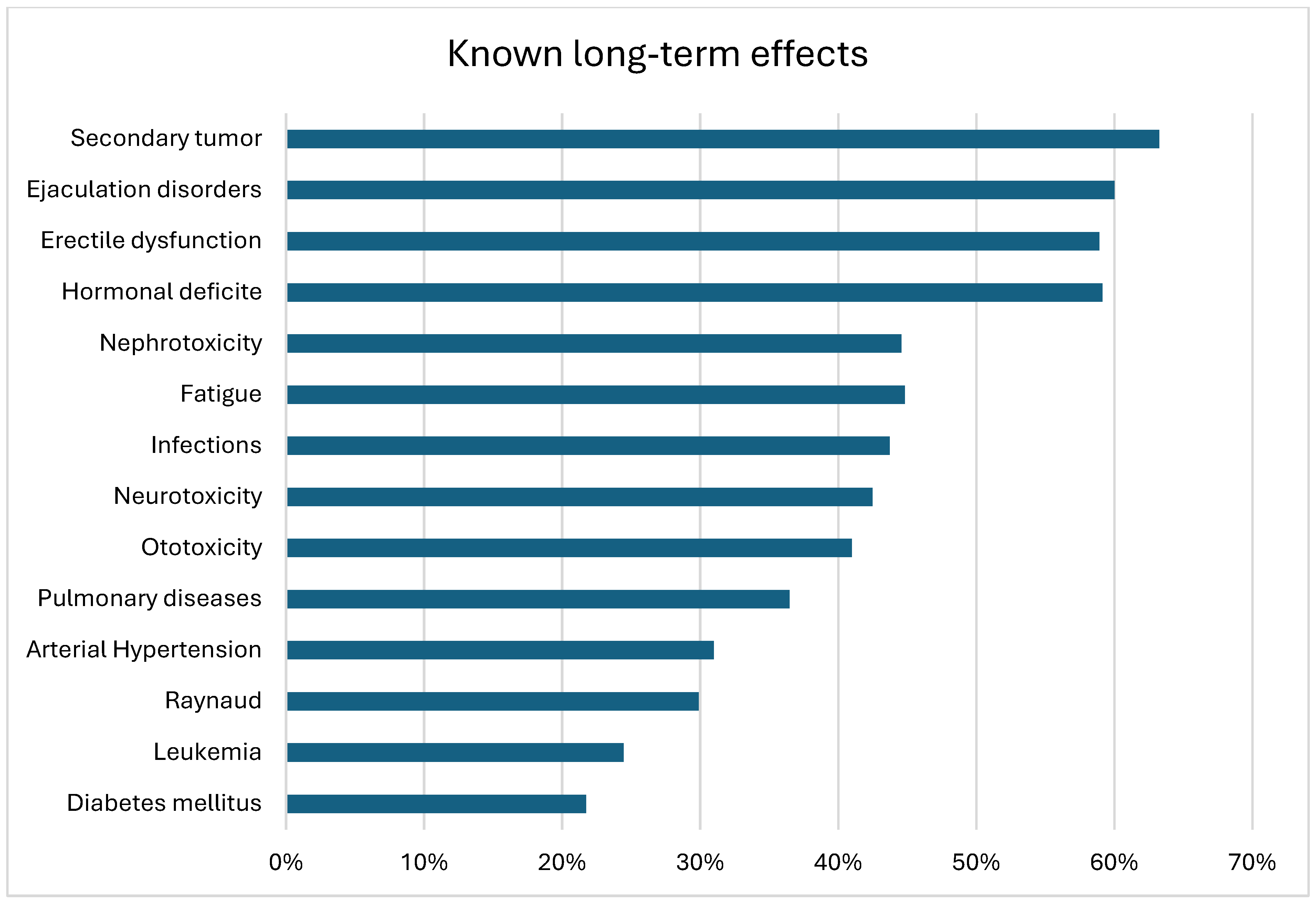

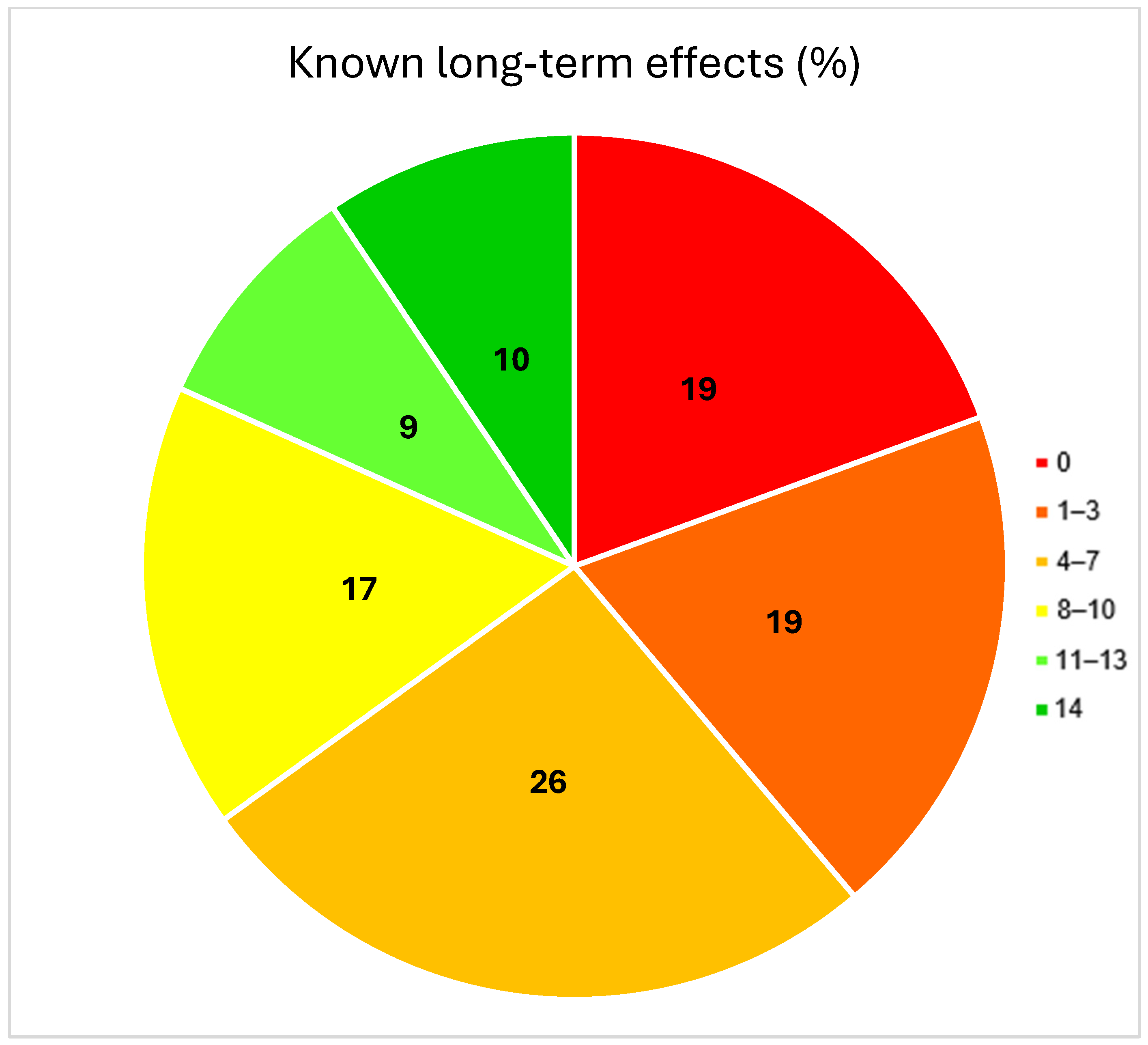

3.2. Patient Knowledge

3.3. Risk Factors for Lack of Knowledge About Long-Term Effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bertz, J.; Buttmann-Schweiger, N.; Kraywinkel, K. Epidemiologie bösartiger Hodentumoren in Deutschland. Der Onkol. 2017, 23, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazici, S.; Del Biondo, D.; Napodano, G.; Grillo, M.; Calace, F.P.; Prezioso, D.; Crocetto, F.; Barone, B. Risk Factors for Testicular Cancer: Environment, Genes and Infections-Is It All? Medicina 2023, 59, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einhorn, L.H. Curing metastatic testicular cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 4592–4595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krebs in Deutschland für 2019/2020, 14th ed.; Robert Koch-Institut (Hrsg) und Die Gesellschaft der Epidemiologischen Krebsregister in Deutschland e.V. (Hrsg): Berlin, Germany, 2023.

- Chovanec, M.; Abu Zaid, M.; Hanna, N.; El-Kouri, N.; Einhorn, L.; Albany, C. Long-term toxicity of cisplatin in germ-cell tumor survivors. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 2670–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, V.; Dinh, P.C., Jr.; Fung, C.; Monahan, P.O.; Althouse, S.K.; Norton, K.; Cary, C.; Einhorn, L.; Fossa, S.D.; Adra, N.; et al. Adverse Health Outcomes Among US Testicular Cancer Survivors After Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy vs. Surgical Management. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2020, 4, pkz079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakob, A.; Kollmannsberger, C.; Kanz, L.; Bokemeyer, C. Late toxicity after chemotherapy of malignant testicular tumors. Urol. A 1998, 37, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugnes, H.S.; Bosl, G.J.; Boer, H.; Gietema, J.A.; Brydoy, M.; Oldenburg, J.; Dahl, A.A.; Bremnes, R.M.; Fosså, S.D. Long-term and late effects of germ cell testicular cancer treatment and implications for follow-up. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 3752–3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliesch, S.; Schmidt, S.; Wilborn, D.; Aigner, C.; Albrecht, W.; Bedke, J.; Beintker, M.; Beyersdorff, D.; Bokemeyer, C.; Busch, J.; et al. Management of Germ Cell Tumours of the Testes in Adult Patients: German Clinical Practice Guideline, PART II—Recommendations for the Treatment of Advanced, Recurrent, and Refractory Disease and Extragonadal and Sex Cord/Stromal Tumours and for the Management of Follow-Up, Toxicity, Quality of Life, Palliative Care, and Supportive Therapy. Urol. Int. 2021, 105, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beyer, J.; Albers, P.; Altena, R.; Aparicio, J.; Bokemeyer, C.; Busch, J.; Cathomas, R.; Cavallin-Stahl, E.; Clarke, N.W.; Claßen, J.; et al. Maintaining success, reducing treatment burden, focusing on survivorship: Highlights from the third European consensus conference on diagnosis and treatment of germ-cell cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.S.; Ma, C.T.; Chan, C.H.; Luk, M.S.; Woo, H.K.; Lee, V.W.; Leung, A.W.K.; Lee, S.L.; Yeung, N.C.; Li, C.; et al. Awareness of diagnosis, treatment and risk of late effects in Chinese survivors of childhood cancer in Hong Kong. Health Expect. 2021, 24, 1473–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landier, W.; Chen, Y.; Namdar, G.; Francisco, L.; Wilson, K.; Herrera, C.; Armenian, S.; Wolfson, J.A.; Sun, C.L.; Wong, F.L.; et al. Impact of Tailored Education on Awareness of Personal Risk for Therapy-Related Complications Among Childhood Cancer Survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 3887–3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, I.A.; Klassen, A.F.; Barr, R.; Wang, R.; Dix, D.; Nelson, M.; Rosenberg-Yunger, Z.R.; Nathan, P.C. Factors associated with childhood cancer survivors’ knowledge about their diagnosis, treatment, and risk for late effects. J. Cancer Surviv. 2016, 10, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadan-Lottick, N.S.; Robison, L.L.; Gurney, J.G.; Neglia, J.P.; Yasui, Y.; Hayashi, R.; Hudson, M.; Greenberg, M.; Mertens, A.C. Childhood cancer survivors’ knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment: Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA 2002, 287, 1832–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksoy, C.; Ihrig, A.; Reimold, P.; Tosev, G.; Himmelsbach, R.; Jesser, J.; Babayigit, G.; Huber, J. Better Knowledge about Testicular Cancer Might Improve the Rate of Testicular (Self-)Examination: A Survey among 1025 Medical Students in Germany. Urol. Int. 2022, 106, 1056–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, R.I.H.; Leow, J.J.; Choo, Z.W.; Salada, R.; Yong, D.Z.P.; Chong, Y.L. Testicular self-examination for early detection of testicular cancer. World J. Urol. 2023, 41, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, N.; Raj, A.; Santhosh, A.P.; Kumar, S.; Haresh, K.P.; Singh, P.; Nayak, B.; Shamim, S.A.; Seth, A.; Ray, M.; et al. Quality of life assessment in testicular non-seminomatous germ cell tumour survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2024, 18, 1747–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzelbecker, J.; Kassmann, K.; Ernst, S.; Meyer-Mabileau, P.; Germanyuk, A.; Zangana, M.; Wagenpfeil, G.; Ohlmann, C.H.; Cohausz, M.; Stöckle, M.; et al. Long-term quality of life of testicular cancer survivors differs according to applied adjuvant treatment and tumour type. J. Cancer Surviv. 2024. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, T.; Robinson, D.; Shamash, J.; Moller, H.; Tranter, N.; Oliver, T. The long-term risks of adjuvant carboplatin treatment for stage I seminoma of the testis. Ann. Oncol. 2008, 19, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoogh, J.; Steineck, G.; Johansson, B.; Wilderang, U.; Stierner, U.; SWENOTECA. Psychological needs when diagnosed with testicular cancer: Findings from a population-based study with long-term follow-up. BJU Int. 2013, 111, 1287–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EAU Guidelines. Edn. Presented at the EAU Annual Congress Milan 2023; EAU Guidelines Office: Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2023.

- Weda, S.; Zweers, D.; Suelmann, B.B.M.; Meijer, R.P.; Vervoort, S. From Surviving Cancer to Getting on with Life: Adult Testicular Germ Cell Tumor Survivors’ Perspectives on Transition from Follow-Up Care to Long-Term Survivorship. Qual. Health Res. 2023, 33, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, A.H.; Howell, D.; Edwards, E.; Warde, P.; Matthew, A.; Jones, J.M. The experience of patients with early-stage testicular cancer during the transition from active treatment to follow-up surveillance. Urol. Oncol. 2016, 34, 168.e11–168.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvammen, O.; Myklebust, T.A.; Solberg, A.; Moller, B.; Klepp, O.H.; Fossa, S.D.; Tandstad, T. Long-term Relative Survival after Diagnosis of Testicular Germ Cell Tumor. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2016, 25, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, A.; Chovanec, M.; Oliva, V.; Sedliak, M.; Mego, M.; Ukropec, J.; Ukropcová, B. Chemotherapy-induced toxicity in patients with testicular germ cell tumors: The impact of physical fitness and regular exercise. Andrology 2021, 9, 1879–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All (n = 198) | Carboplatin (n = 70) | Complex Chemotherapy (n = 128) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at survey (years) | 44.6 ± 12.2 44 (22–81) | 48.8 ± 11.6 48 (30–73) | 42.3 ± 11.9 40 (22–81) | <0.001 | |

| Follow-up year (Years) | 5.3 ± 2.9 5 (1–12) | 5.7 ± 2.7 6 (1–10) | 5.0 ± 3.0 5 (1–12) | 0.1 | |

| Histology | Seminoma | 137 (69%) | 70 (100%) | 67 (52%) | <0.001 |

| Non-Seminoma | 61 (31%) | 0 (0%) | 61 (48%) | ||

| Clinical Stage | I | 120 (60%) | 69 (100%) | 51 (40%) | <0.001 |

| II | 49 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 49 (38%) | ||

| III | 29 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 29 (22%) | ||

| Prognosis group | Good | 60 (78%) | 0 (0%) | 60 (78%) | n.a. |

| Intermediate | 9 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (12%) | ||

| Poor | 8 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (10%) | ||

| Number of chemotherapy cycles | 1–2 | 103 (52%) | 70 (100%) | 33 (26%) | <0.001 |

| 3+ | 95 (48%) | 0 (0%) | 95 (74%) | ||

| Retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy | Yes | 36 (18%) | 2 (3%) | 34 (27%) | <0.001 |

| No | 162 (82%) | 68 (97%) | 94 (73%) | ||

| Educational level (n = 192) | Secondary school or no qualification | 105 (53%) | 36 (54%) | 69 (55%) | 0.8 |

| High school | 87 (47%) | 31 (46%) | 56 (45%) | ||

| Marital status (n = 197) | Single | 66 (34%) | 15 (22%) | 51 (40%) | 0.01 |

| In partnership | 131 (66%) | 54 (78%) | 77 (60%) | ||

| Household income (n = 181) | <1500 € | 23 (13%) | 6 (10%) | 17 (14%) | 0.2 |

| 1500–4000 € | 110 (60%) | 35 (55%) | 75 (64%) | ||

| >4000 € | 48 (27%) | 22 (35%) | 26 (22%) | ||

| Health insurance | Statutory | 178 (90%) | 58 (83%) | 120 (94%) | 0.02 |

| Private | 20 (10%) | 12 (17%) | 8 (6%) | ||

| All (n = 198) | Carboplatin (n = 70) | Complex Chemotherapy (n = 128) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy according to patient | Yes | 188 (95%) | 67 (96%) | 121 (95%) | 0.5 |

| No | 6 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 5 (4%) | ||

| I am not aware of | 4 (2%) | 2 (3%) | 2 (1%) | ||

| Knowledge about chemotherapy name (n = 188) | Name known | 85 (45%) | 24 (36%) | 61 (50%) | 0.2 |

| Inaccurate/incorrect information | 72 (38%) | 30 (45%) | 42 (35%) | ||

| Not specified | 31 (17%) | 13 (19%) | 18 (15%) | ||

| Knowledge of the tumor (n = 194) | Yes | 87 (45%) | 32 (48%) | 55 (43%) | 0.6 |

| No | 107 (55%) | 35 (52%) | 72 (57%) | ||

| Konwledge of tumor type | No/unclear information | 122 (62%) | 46 (66%) | 76 (59%) | 0.3 |

| testicular tumor | 10 (5%) | 5 (7%) | 5 (4%) | ||

| Seminoma/Non-Seminoma | 66 (33%) | 19 (27%) | 47 (37%) | ||

| Frequency of palpation of the testicle (n = 190) | Daily | 20 (10%) | 8 (12%) | 12 (10%) | 1.0 |

| Weekly | 84 (44%) | 29 (43%) | 55 (45%) | ||

| Monthly | 41 (22%) | 15 (22%) | 26 (21%) | ||

| Annually | 11 (6%) | 4 (6%) | 7 (6%) | ||

| Never | 34 (18%) | 12 (17%) | 22 (18%) | ||

| Knowledge about relevant CTx long-term effects | ≤30% | 119 (60%) | 56 (80%) | 63 (49%) | <0.001 |

| >30% | 79 (40%) | 14 (20%) | 65 (51%) | ||

| All (n = 198) | Lack of Knowledge (0–30%) (n = 119) | Knowledge (40–100%) (n = 79) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical stage | I | 120 (60%) | 83 (70%) | 37 (47%) | 0.005 |

| II | 49 (25%) | 23 (19%) | 26 (33%) | ||

| III | 29 (15%) | 13 (11%) | 16 (20%) | ||

| Prognosis group | Good | 60 (78%) | 28 (80%) | 32 (76%) | 0.9 |

| Intermediate | 9 (12%) | 4 (11%) | 5 (12%) | ||

| Poor | 8 (10%) | 3 (9%) | 5 (12%) | ||

| Histology | Seminoma | 137 (69%) | 90 (76%) | 47 (59%) | 0.02 |

| Non-Seminoma | 61 (31%) | 29 (24%) | 32 (41%) | ||

| Retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy | Yes | 36 (18%) | 15 (13%) | 21 (27%) | 0.01 |

| No | 162 (82%) | 104 (87%) | 58 (73%) | ||

| Type of chemotherapy | Carboplatin | 70 (35%) | 56 (47%) | 14 (18%) | <0.001 |

| Complex | 128 (65%) | 63 (53%) | 65 (82%) | ||

| Number of chemotherapy cycles | 1–2 | 103 (52%) | 73 (61%) | 30 (25%) | 0.001 |

| ≥3 | 95 (48%) | 46 (39%) | 49 (75%) | ||

| Marital status (n = 197) | Partnership | 131 (66%) | 81 (69%) | 50 (63%) | 0.4 |

| Single | 66 (34%) | 37 (31%) | 29 (37%) | ||

| Educational level (n = 192) | Secondary school or lower | 105 (53%) | 71 (62%) | 34 (44%) | 0.01 |

| High school | 87 (47%) | 43 (38%) | 44 (56%) | ||

| Age at interview | 44.5 ± 12.2 44 (22–81) | 46.9 ± 12.5 48 (22–81) | 41.2 ± 10.9 39 (22–71) | <0.001 | |

| Follow-up year after chemotherapy | 5.3 ± 2.9 5 (1–12) | 5.5 ± 2.8 6 (1–12) | 4.9 ± 3.1 5 (1–12) | 0.1 | |

| Household income (n = 181) | <1500 € | 23 (13%) | 17 (16%) | 6 (8%) | 0.3 |

| 1500–4000 € | 110 (60%) | 64 (59%) | 46 (63%) | ||

| >4000 € | 48 (27%) | 27 (25%) | 21 (29%) | ||

| Health insurance | Statutory | 178 (90%) | 109 (92%) | 69 (87%) | 0.3 |

| Private | 20 (10%) | 10 (8%) | 10 (13%) | ||

| Knowledge of chemotherapy name (n = 188) | Yes | 85 (45%) | 35 (32%) | 50 (63%) | <0.001 |

| No | 103 (55%) | 74 (68%) | 29 (37%) | ||

| Parameters | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p-Value | OR | p-Value | |

| Clinical Stage (Stage I) | 2.6 (1.5–4.7) | 0.001 | 1.7 (0.7–4.1) | 0.2 |

| Histology (seminoma) | 2.1 (1.1–3.9) | 0.02 | 0.9 (0.4–2.0) | 0.8 |

| Retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy (no) | 2.5 (1.2–5.2) | 0.01 | 1.5 (0.6–3.6) | 0.4 |

| Type of chemotherapy (Carboplatin) | 4.1 (2.1–8.2) | <0.001 | 3.2 (1.1–9.4) | 0.04 |

| Chemotherapy cycles (1–2 cycles) | 2.6 (1.4–4.7) | 0.001 | 0.8 (0.3–2.1) | 0.6 |

| Educational degree (secondary school or lower) | 2.1 (1.2–3.8) | 0.01 | 2.2 (1.2–4.3) | 0.02 |

| Age (>44 years) | 2.6 (1.4–4.6) | 0.002 | 1.8 (0.9–3.5) | 0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buerk, B.T.; Helke, C.; Richter, E.; Menzel, V.; Borkowetz, A.; Thomas, C.; Baunacke, M. Knowledge Deficit About How Chemotherapy Affects Long-Term Survival in Testicular Tumor Patients. Cancers 2025, 17, 565. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17040565

Buerk BT, Helke C, Richter E, Menzel V, Borkowetz A, Thomas C, Baunacke M. Knowledge Deficit About How Chemotherapy Affects Long-Term Survival in Testicular Tumor Patients. Cancers. 2025; 17(4):565. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17040565

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuerk, Bjoern Thorben, Charlotte Helke, Emilia Richter, Viktoria Menzel, Angelika Borkowetz, Christian Thomas, and Martin Baunacke. 2025. "Knowledge Deficit About How Chemotherapy Affects Long-Term Survival in Testicular Tumor Patients" Cancers 17, no. 4: 565. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17040565

APA StyleBuerk, B. T., Helke, C., Richter, E., Menzel, V., Borkowetz, A., Thomas, C., & Baunacke, M. (2025). Knowledge Deficit About How Chemotherapy Affects Long-Term Survival in Testicular Tumor Patients. Cancers, 17(4), 565. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17040565