Breast Cancer in Men and Quality of Life: A Systematic Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

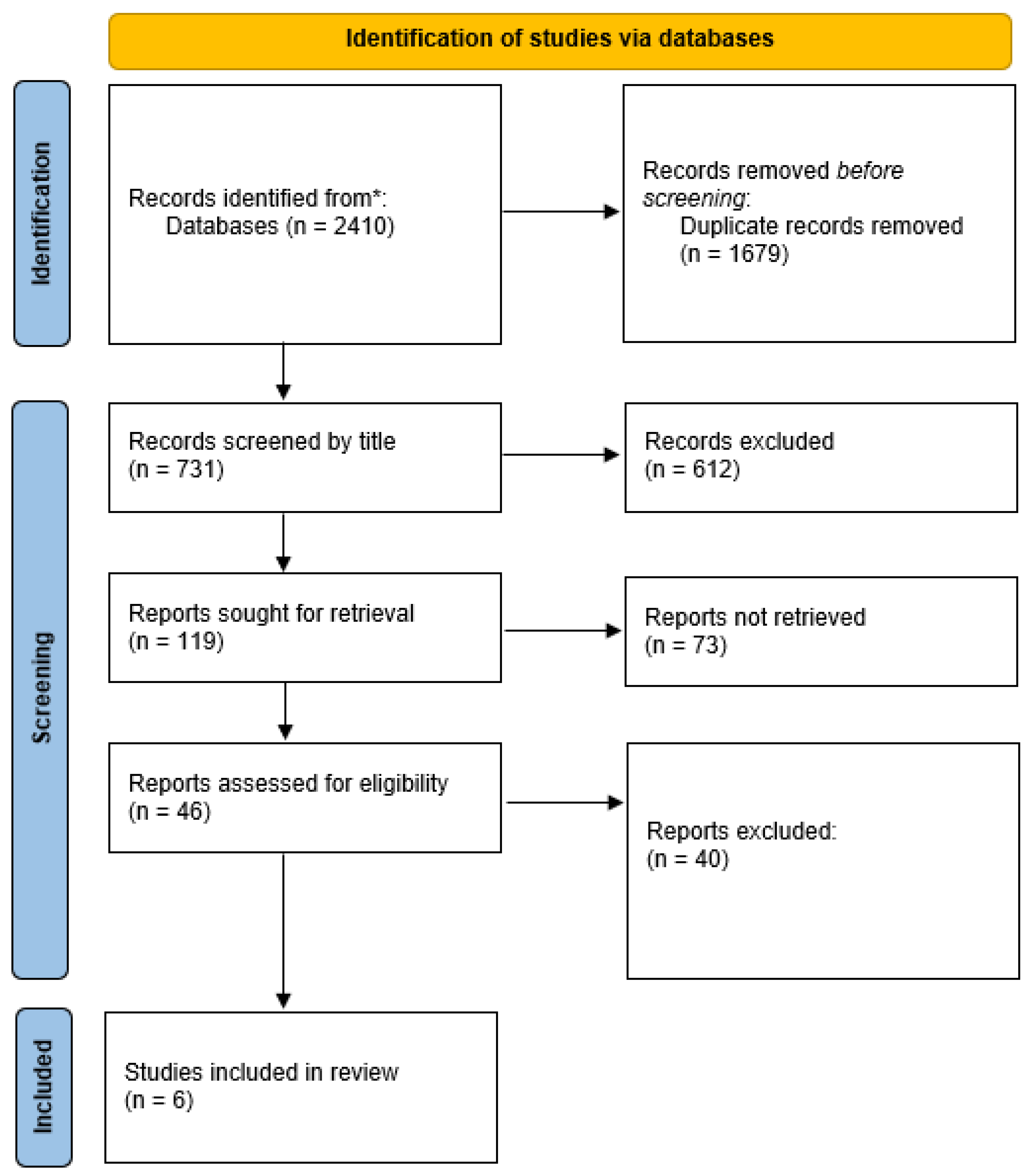

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria for Studies

2.3. Data Extraction (Selection and Coding)

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haraldstad, K.; Wahl, A.; Andenæs, R.; Andersen, J.R.; Andersen, M.H.; Beisland, E.; Borge, C.R.; Engebretsen, E.; Eisemann, M.; Halvorsrud, L.; et al. A systematic review of quality of life research in medicine and health sciences. Qual. Life Res. 2019, 28, 2641–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomé, B.; Dykes, A.; Hallberg, I. Quality of life in old people with and without cancer. Qual. Life Res. 2004, 13, 1067–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, N.E. ISOQOL Dictionary of Quality of Life and Health Outcomes Measurement; International Society for Quality of Life Research: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Efficace, F.; Bottomley, A.; Coens, C.; Van Steen, K.; Conroy, T.; Schöffski, P.; Schmolle, H.; Van Cutsem, E.; Köhne, C.H. Does a patient’s self-reported health-related quality of life predict survival beyond key biomedical data in advanced colorectal cancer? Eur. J. Cancer 2006, 42, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotay, C.C.; Kawamoto, C.T.; Bottomley, A.; Efficace, F. The prognostic significance of patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 1355–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, C.; Paul, S.; Dunn, L.; Dhruva, A.; Merriman, J.; Miaskowski, C. Gender differences in predictors of quality of life at the initiation of radiation therapy. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2015, 42, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dibble, S.L.; Padilla, G.V.; Dodd, M.J.; Miaskowski, C. Gender differences in the dimensions of quality of life. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 1998, 25, 577–583. [Google Scholar]

- Cherepanov, D.; Palta, M.; Fryback, D.G.; Robert, S.A. Gender differences in health-related quality-of-life are partly explained by sociodemographic and socioeconomic variation between adult men and women in the US: Evidence from four US nationally representative data sets. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, A.; Singer, S.; Brähler, E. European reference values for the quality of life questionnaire EORTC QLQ-C30: Results of a German investigation and a summarizing analysis of six European general population normative studies. Acta Oncol. 2014, 53, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juul, T.; Petersen, M.A.; Holzner, B.; Laurberg, S.; Christensen, P.; Grønvold, M. Danish population-based reference data for the EORTC QLQ-C30: Associations with gender, age and morbidity. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 2183–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielck, A.; Vogelmann, M.; Leidl, R. Health-related quality of life and socioeconomic status: Inequalities among adults with a chronic disease. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2014, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, C.D.; Reeves, M.J.; Zhao, X.; Pan, W.; Prvu-Bettger, J.; Zimmer, L.; Olson, D.; Peterson, E. Sex differences in quality of life after ischemic stroke. Neurology 2014, 82, 922–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, J.; Dogan, I.; Schulz, J.B.; Reetz, K. Evidence for gender differences in cognition, emotion and quality of life in Parkinson’s disease? Aging Dis. 2014, 5, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjermstad, M.J.; Fayers, P.M.; Bjordal, K.; Kaasa, S. Using reference data on quality of life—The importance of adjusting for age and gender, exemplified by the EORTC QLQ-C30 (+3). Eur. J. Cancer 1998, 34, 1381–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.G.; Hwang, J.Y.; Uhmn, S.; Go, M.J.; Oh, B.; Lee, J.Y.; Park, J.W. Male-specific genetic effect on hypertension and metabolic disorders. Hum. Genet. 2014, 133, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopman, W.M.; Coo, H.; Pavlov, A.; Day, A.G.; Edgar, C.M.; McBride, E.V.; Brunet, D.G. Multiple sclerosis: Change in health-related quality of life over two years. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2009, 36, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Krouse, R.S.; Herrinton, L.J.; Grant, M.; Wendel, C.S.; Green, S.B.; Mohler, M.J.; Baldwin, C.M.; McMullen, C.K.; Rawl, S.M.; Matayoshi, E.; et al. Health-related quality of life among long-term rectal cancer survivors with an ostomy: Manifestations by sex. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 4664–4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisspers, K.; Ställberg, B.; Janson, C.; Johansson, G.; Svärdsudd, K. Sex-differences in quality of life and asthma control in Swedish asthma patients. J. Asthma 2013, 50, 1090–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osann, K.; Hsieh, S.; Nelson, E.L.; Monk, B.J.; Chase, D.; Cella, D.; Wenzel, L. Factors associated with poor quality of life among cervical cancer survivors: Implications for clinical care and clinical trials. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 135, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashos, C.L.; Flowers, C.R.; Kay, N.E.; Weiss, M.; Lamanna, N.; Farber, C.; Lerner, S.; Sharman, J.; Grinblatt, D.; Flinn, I.W.; et al. Association of health-related quality of life with gender in patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 2853–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pud, D. Gender differences in predicting quality of life in cancer patients with pain. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2011, 15, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Khanlou, N. An analysis of Canadian psychiatric mental health nursing through the junctures of history, gender, nursing education, and quality of work life in Ontario, Manitoba, Alberta, and Saskatchewan. ISRN Nurs. 2013, 2013, 184024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, C.; Burman, D.; Swami, N.; Krzyzanowska, M.K.; Leighl, N.; Moore, M.; Rodin, G.; Tannock, I. Determinants of quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2011, 19, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midding, E.; Halbach, S.M.; Kowalski, C.; Weber, R.; Würstlein, R.; Ernstmann, N. Men with a “woman’s disease”: Stigmatization of male breast cancer patients—A mixed methods analysis. Am. J. Mens Health 2018, 12, 2194–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddy, K.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Giordano, S.; Goldfarb, S.; Kereakoglow, S.; Winer, E.; Partridge, A. Quality of life and symptoms in male breast cancer survivors. Breast 2013, 22, 197–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konduri, S.; Singh, M.; Bobustuc, G.; Rovin, R.; Kassam, A. Epidemiology of male breast cancer. Breast 2020, 54, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iredale, R.; Brain, K.; Williams, B.; France, E.; Gray, J. The experiences of men with breast cancer in the United Kingdom. Eur. J. Cancer 2006, 42, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greif, J.M.; Pezzi, C.M.; Klimberg, V.S.; Bailey, L.; Zuraek, M. Gender differences in breast cancer: Analysis of 13,000 breast cancers in men from the National Cancer Data Base. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 19, 3199–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautrup, M.D.; Thorup, S.S.; Jensen, V.; Bokmand, S.; Haugaard, K.; Hoejris, I.; Jylling, A.-M.B.; Joernsgaard, H.; Lelkaitis, G.; Oldenburg, M.H.; et al. Male breast cancer: A nation-wide population-based comparison with female breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2018, 57, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Johnson, K.J.; Ma, C.X. Male breast cancer: An updated surveillance, epidemiology, and end results data analysis. Clin. Breast Cancer 2018, 18, e997–e1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, M. Breast cancer in men: The importance of teaching and raising awareness. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2010, 14, 31–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Smith, H. Breast cancer or chest cancer? The impact of living with a ‘woman’s disease’. J. Aesthetic Nurs. 2016, 5, 240–241. [Google Scholar]

- Guarinoni, M.; Motta, P. The experience of men with breast cancer: A metasynthesis. J. Public Health 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari-Hesari, P.; Montazeri, A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: Review of reviews from 2008 to 2018. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardin, S.; Mora, E.; Varughese, F.M.; D’Avanzo, F.; Vachanaram, A.R.; Rossi, V.; Saggia, C.; Rubinelli, S.; Gennari, A. Breast cancer survivorship, quality of life, and late toxicities. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidary, Z.; Ghaemi, M.; Hossein Rashidi, B.; Kohandel Gargari, O.; Montazeri, A. Quality of life in breast cancer patients: A systematic review of the qualitative studies. Cancer Control 2023, 30, 10732748231168318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanei Gheshlagh, R.; Mohammadnejad, E.; Dalvand, S.; Dehkordi, A.H. Health-related quality of life in patients with breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Dis. 2022, 41, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, C.; Bai, D.; Gao, J.; Hou, C.; Chen, T.; Zhang, L.; Luo, H. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients in Asia: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 954179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrykowski, M.A. Physical and mental health status and health behaviors in male breast cancer survivors: A national, population-based, case-control study. Psychooncology 2012, 21, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, C.; Steffen, P.; Ernstmann, N.; Wuerstlein, R.; Harbeck, N.; Pfaff, H. Health-related quality of life in male breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012, 133, 753–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouhi, M.E.; Rahou, B.H.; Mesfioui, A.; Benider, A. Quality of life and epidemiological profile of male breast cancer treated at the university hospital of Casablanca, Morocco. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2022, 41, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, J.; Herrick, B.; Attai, D.J.; Leone, J.P. Treatments for breast cancer in men: Late effects and impact on quality of life. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2023, 201, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, C.; van Leeuwen-Stok, E.; Cardoso, F.; Linderholm, B.; Poncet, C.; Wolff, A.; Ruddy, K. Quality of Life in Male Breast Cancer: Prospective Study of the International Male Breast Cancer Program (EORTC10085/TBCRC029/BIG2-07/NABCG). Oncologist 2023, 28, e877–e883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeisi Dehkordi, S.; Kennedy, S.K.F.; Peera, M.; Wong, H.C.Y.; Lee, S.F.; Alkhaifi, M.; Carmona Gonzalez, C.A. Examining stigma in experiences of male breast cancer patients and its impact as a barrier to care: A narrative review. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2024, 13, 1291–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiteni, F.; Ray, I.L.; Ousmen, A.; Isambert, N.; Anota, A.; Bonnetain, F. Health-related quality of life as an endpoint in oncology phase I trials: A systematic review. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemmaraju, N.; Munsell, M.F.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Giordano, S.H. Retrospective review of male breast cancer patients: Analysis of tamoxifen-related side-effects. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 1471–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter-Zakarian, A.; Agelidis, A.; Jaloudi, M. Male Breast Cancer: Evaluating the Current Landscape of Diagnosis and Treatment. Breast Cancer 2025, 17, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Author | Journal | Title | Country | Purpose | Study Type | Population | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Andrykowski MA [41] | Psychooncology | Physical and mental health status and health behaviors in male breast cancer survivors: a national, population-based, case-control study | USA | To examine current physical and mental health status and health behaviors in male breast cancer survivors | CASE-CONTROL | 66 MBC 198 male with no history of cancer | The diagnosis and treatment of male breast cancer may be associated with clinically important and long-term deficits in physical and mental health status, deficits which may exceed those evidenced by long-term female breast cancer survivors |

| 2012 | Kowalski C et al. [42] | Breast Cancer Res Treat | Health-related quality of life in male breast cancer patients | Germany | The aim of the study was to compare the quality of healthcare provided in the individual breast centers as perceived by the patients. A secondary objective was to describe the HRQOL of the patients. | Descriptive | 84 MBC WBC and male without cancer | Male breast cancer patients may need early interventions that specifically target role functioning, which is severely impaired compared to the male reference population. |

| 2013 | Ruddy KJ et al. [26] | Breast | Quality of life and symptoms in male breast cancer survivors. | USA | To learn more about symptoms, quality of life, distress, and fertility and genetic issues in male breast cancer survivors. | Survey | 42 MBC | With mean EPIC Sexual and Hormonal scores of 44.5 and 81.3, patients reported a considerable symptom burden. The mean FACT-B score of 111.1 also pointed to an impaired overall quality of life. While care for men with breast cancer often mirrors that for women, men’s unique experiences with the disease and their specific concerns during survivorship remain. |

| 2022 | Fouhi ME et al. [43] | Pan Afr Med J | Quality of life and epidemiological profile of male breast cancer treated at the university hospital of Casablanca, Morocco | Morocco | To investigate health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and epidemiological profile of Moroccan male breast cancer patients at the university hospital of Casablanca Ibn Rochd | Descriptive | 21 MBC | Regarding QOL in this population, it appears to be better than expected and QOL generally improves after treatment. As for prevention, public education should be oriented toward men at higher risk in order to reduce the time between onset of symptoms and consultation. |

| 2023 | Avila J et al. [44] | Breast Cancer Res Treat | Treatments for breast cancer in men: late effects and impact on quality of life. | USA | To survey this particular group of patients about their experience with BC. | Survey | 127 MBC | The study provides critical information on several side effects and late effects that are experienced by male patients with breast cancer. Further research is necessary to mitigate the impact of these effects and improve quality of life in men. |

| 2023 | Schröder CP et al. [45] | Oncologist | Quality of Life in Male Breast Cancer: Prospective Study of the International Male Breast Cancer Program | International | To assess quality of life (QOL) and symptom burden, which have been woefully understudied in male BC. | Survey | 363 MBC WBC | This large prospective registry substudy demonstrates that overall QOL is good in men who were recently diagnosed with breast cancer, but some still suffer appetite loss, fatigue, and insomnia. Sexual functioning may also be an issue. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guarinoni, M.G.; Motta, P.C. Breast Cancer in Men and Quality of Life: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 3096. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193096

Guarinoni MG, Motta PC. Breast Cancer in Men and Quality of Life: A Systematic Review. Cancers. 2025; 17(19):3096. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193096

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuarinoni, Milena Giovanna, and Paolo Carlo Motta. 2025. "Breast Cancer in Men and Quality of Life: A Systematic Review" Cancers 17, no. 19: 3096. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193096

APA StyleGuarinoni, M. G., & Motta, P. C. (2025). Breast Cancer in Men and Quality of Life: A Systematic Review. Cancers, 17(19), 3096. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17193096