Simple Summary

Wound complications are a frequent and significant challenge in vulvar cancer surgery. However, reported rates of wound complications in the literature vary widely, and the underlying risk factors remain insufficiently understood. This study shows that larger tumors, tumors involving the urethra, or located near the urethra or the perineum are at higher risk of especially wound breakdowns. Primary skin closure can be challenging due to tension and anatomical disruption, often requiring reconstructive surgery to restore form and function. Although reconstruction is associated with higher wound complication rates and longer hospital stays—likely due to the complexity of these selected cases—it can improve quality of life for selected patients. Reconstructive surgery is best reserved for large tumors, urethral involvement, or tumors located near the urethra or on the perineum. In contrast, small tumors suitable for primary closure may not benefit from reconstructive surgery. Multidisciplinary planning is essential to indicate the use of reconstructive surgery.

Abstract

Objective: Vulvar cancer surgery is associated with high postoperative wound complication rates. Reconstructive surgery (RS) in vulvar cancer is generally reserved for surgery of extensive tumors or local recurrences. The primary aim of the study is to determine the incidence and risk factors for wound complications after vulvar cancer surgery. As a secondary aim, we compare the effects of primary closure (PC) versus reconstructive surgery on wound complications. Methods: In a retrospective cohort study in four gynecologic oncology centers in the Netherlands, patients undergoing surgical treatment (2018–2022) for vulvar cancer were included. Wound complications after PC and RS and risk factors associated with complications were analyzed by using logistic regression adjusting for confounds. Results: We included 394 women, 318 with PC and 76 with RS. The incidence of wound complications was 46.7%, with 42.4% of wound breakdowns comprising the majority of complications. The use of RS was associated with an increased risk of wound complications. Larger tumor size, proximity to the urethra, resection of the urethra during surgery, and perineal tumor location were additional risk factors for wound complications. However, after multivariate analyses, RS remained the only significant risk factor (OR 1.2; 95% CI 1.1–1.2). Conclusions: Risk factors for wound complications after vulvar cancer surgery include larger tumor size, proximity to the urethra, resection of the urethra during surgery, and perineal tumor location. RS is also associated with an increased risk of wound complications, probably related to case selection.

1. Introduction

Vulvar cancers are relatively uncommon, with a higher and increasing incidence in Europe and North America. Worldwide, up to 42,240 women were diagnosed with vulvar cancer in 2020 [1,2]. In the Netherlands, 456 new cases of vulvar cancer were reported in 2023 [3]. The vast majority of vulvar cancers are squamous cell carcinoma (VSCC) (70–90%), and the minority are basal cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and melanoma. Vulvar cancer usually presents as a persistent vulvar lesion, ulceration, itching, or pain [4]. Over the last few years, there has been a striking increase in incidence, mainly in women aged <60 years [5]. VSCC has a 5-year survival rate of 75%, which varies significantly by stage, from 84% in FIGO stage I to 35% in FIGO stage IV [6].

VSCC development distinguishes two pathophysiological pathways; the human papillomavirus positive pathway (HPV+), which accounts for approximately 20% of all vulvar cancers, and HPV-negative tumors, which account for the remaining 80% [7]. HPV-positive tumors have the most favorable outcomes in terms of overall survival, relative survival (RS), and recurrence-free period (RFD) [8]. The HPV-negative pathway is caused by dysplastic changes in the vulvar epithelium associated with lichen sclerosis (LS) [9]. Differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN) is the main precursor for HPV-negative VSCC [10]. Recently, within the HPV-negative pathway, a distinct vulvar cancer cohort is identified by subclassification upon mutations in the p53 gene [8]. The HPV-negative/p53 mutant cohort, accounting for 15% of VSCC, has the worst survival and tends to recur more often compared to the HPV-negative/p53 wild-type VSCC cohort, accounting for 66% of vulvar cancers in this study [8].

Despite different pathophysiological pathways of VSCC the treatment of vulvar cancer at present is similar and consists of a surgical resection in the majority of patients or chemo- and/or radiotherapy in case of more advanced stages [10]. Vulvar surgery aims to radically remove the vulvar cancer lesion with clear margins and minimize the effect on the surrounding tissue and functional anatomical critical structures [11,12,13]. In surgical treatment for early stage VSCC a wide local tumor resection (WLE) is in general combined with either groin surgery by sentinel node (SN) procedure or inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy (IFL) [7,8,9,10].

Vulvar surgery is often experienced as mutilating by anatomical distortion and has a severe negative impact on functional, psychological, and sexual functioning [14]. Surgical complications are common in vulvar cancer surgery and increase with the extent and level of radicality of surgery [15]. Wound complication rates are reported in a wide range of 9% to 58% of patients following vulvectomy [16,17,18]. Risk factors for these wound complications are less well-known and are associated with tumor diameter and combination with groin surgery [15]. Radiotherapy is known to impair wound healing, necessitating careful consideration of this factor when planning (reconstructive) surgery [19].

Depending on the size and location of the tumor, primary skin closure may cause severe tension and difficulty in preserving anatomy and function, necessitating reconstructive surgery with skin transposition to restore the external genitalia post-surgery. Reconstructive surgery may therefore aid in improved quality of life [20]. Different reconstructive techniques in the vulvar area are described as the lotus petal flap, VY-plasty, gracilis or anterolateral thigh (ALT) flap [21]. Research shows that reconstructions with flaps yield more favorable results for perineal tumors than primary closure [22,23,24,25]. A reconstructive technique for vulvar cancer can either be performed by the gynecological oncologist and/or a consulting reconstructive surgeon [3,26].

In this study, we aim to determine the incidence and risk factors for wound complications after vulvar cancer surgery. As a secondary aim, we compare the effects of primary closure versus reconstructive surgery on wound complications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

This retrospective multi-center cohort study was conducted in four tertiary referral centers for vulvar cancer in the Netherlands: Catharina Hospital Eindhoven, Amsterdam University Medical Centers (location AMC), Maastricht University Medical Center, and Radboud University Medical Center Nijmegen. Eligibility criteria were all women diagnosed with a (suspected) primary or recurrent vulvar carcinoma surgically treated in the Catharina Hospital Eindhoven between 2018 and 2021 or in one of the other three between 2018 and 2019. Further inclusion criteria were a minimum age of 18 and surgery planned as treatment in a curative setting. A total of nineteen patients with differentiated Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia (dVIN) have been included because they were suspected of having vulvar cancer preoperatively. Exclusion criteria were previous radiation therapy on the vulva or patients lost to follow-up in the first 6 weeks of follow-up.

2.2. Data Handling and Collection

This study was exempted from formal ethical assessment, as stated by the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO). The study followed the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Institutional approval for this study was obtained from each of the participating centers. Patients’ privacy was protected using anonymized data and maintaining confidentiality throughout the study. Data collection and management were performed using a secure electronic data capture system (Castor eCRF) hosted on a dedicated server. All data were entered directly into the eCRF, and access was restricted to authorized personnel. Collected data included patient and tumor characteristics, operation details, and postoperative variables.

2.3. Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure is the incidence and risk factors for wound complications after vulvar cancer surgery. As a secondary aim, we compare the effects of PC versus RS on wound complications. Wound complications were scored as either one or not multiple (e.g., only breakdown or infection). Variables that were taken into account as possible risk factors included patient characteristics such as age during the procedure, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, comorbidities, and the use of corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, or anticoagulants. Tumor-related factors considered were localization of the tumor, tumor diameter, whether the tumor was primary or recurrent, and proximity to the urethra, clitoris, or midline. Surgical factors included the type of surgical therapy, the closure method of the vulva (e.g., primary closure vs. reconstruction), the use of pre-operative antibiotics, the suture technique and material used, the use of clitoridectomy, and whether resection of the urethra was performed. Postoperative factors, such as the total duration of drainage after surgery, number of days until mobilization, and the sitting schedule during hospitalization, were also taken into account.

2.4. Complication Definitions

Wound complications were categorized as follows: vulvar wound complications occurring during hospitalization or within six weeks postoperatively, including wound breakdown, wound infection, and severe hematoma. Since the literature lacks a definition of wound complications after vulvar surgery, a meeting with four gynecologic oncologists and two reconstructive surgeons was performed. It was determined that if a wound breakdown was mentioned in the medical record, it was documented as such. Wound breakdown was further categorized into three classes. Breakdown of less than 25% of the resection was defined as mild wound breakdown. Breakdown between 25% and 50% was considered moderate. Breakdown exceeding 50% was classified as severe. Wound infections were defined as skin infections requiring antibiotics or surgical debridement. If clinical photographs were available, they were used for the assessment; however, in cases where photographs were not present, we relied on written documentation in the medical records.

2.5. Definition of Tumor-Free Margin

Tumor-free margins were defined as margins in which the pathology report indicated that a surgical margin was tumor-free.

2.6. Data Analysis

Normality was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Continuous variables were summarized using either means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), depending on the distributional characteristics of the data. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and numbers. Analyses and comparisons were performed between primary and reconstructive closure. Numeric data were analyzed using the Student t-test or Mann–Whitney test depending on normality. Categorical data were analyzed using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s Exact test in the case of small numbers. Risk factors for vulvar wound complications were assessed using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. In the univariate logistic regression, we evaluated potential risk factors individually to identify those with a significant association (p < 0.10) with wound complications. This more lenient threshold was applied to avoid the premature exclusion of potentially relevant variables or confounds. Significant factors identified in the univariate analysis were subsequently included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. This allows for assessing the independent effects of these factors on wound complications while adjusting for other variables. Subgroup analyses were performed for different tumor sizes; <2 cm, 2–4 cm and >4 cm. The data was analyzed using SPSS version 29 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences).

3. Results

This study included 394 women surgically treated for vulvar carcinoma during the study period. Overall, patients had a mean age of 69 years, and 20.1% of all patients smoked. Histology of vulvar cancer diagnosis is squamous cell carcinomas in 91.1%, 3.0% melanoma, 4.8% dVIN, and 1.0% adenocarcinoma. Of the included patients, 324 (82.2%) had a primary tumor, and 70 (17.8%) had a recurrent tumor. The mean tumor size was 2.7 cm, and 64.0% of the tumors were located within 1 cm of the midline, with 31.7% of the tumors located anterior (clitoral) and 9.9% of the tumors located posterior (perineal). In 39.3% of the patients, a clitorectomy was required, and in 20.1%, part of the urethra was removed during surgery (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics.

3.1. Wound Complications After Vulvar Cancer Surgery

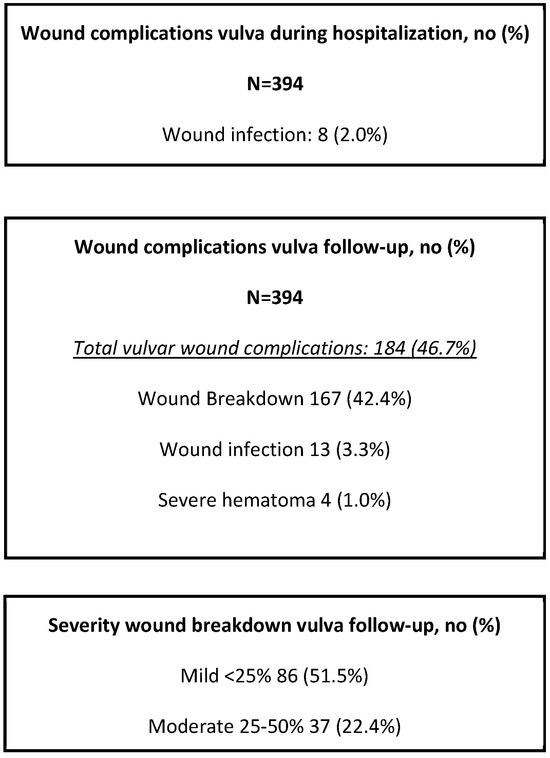

During follow-up, vulvar wound complications were reported in 184 patients (46.7%). Three patients developed wound infections (3.3%), and 167 developed wound breakdowns (42.4%). Of the wound breakdown, 86 of these were mild (51.5%), 37 were moderate (22.4%), and 44 were severe (26.7%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Wound complications after original vulvar surgery during hospitalization and follow-up.

Risk Factors for Wound Complications

A comparison of baseline characteristics and tumor characteristics between the groups with and without wound complications is presented in Table 2. Factors associated with an increased likelihood of wound complications include larger tumor size, with a mean diameter of 3.0 cm in the group with wound complications compared to a mean tumor diameter of 2.4 cm in the group without wound complications (p = 0.001). Furthermore, proximity to the urethra (p = 0.035), resection of the urethra during surgery (p = 0.041), and a perineal tumor location (p = 0.003) are associated with an increased risk of wound complications (Table 2). However, in our multivariate analyses, no significant odds ratios were found (Table 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of patient and tumor characteristics: wound complications vs. no complications.

Table 3.

Univariate logistic regression and multivariate logistic regression analysis for wound complications in patients with vulvar cancer.

3.2. Reconstructive Surgery in Vulvar Cancer Surgery

Reconstructive surgery included various procedures, such as VY-plasty (n = 60), Lotus Petal flaps (n = 12), Gracilis or ALT flaps (n = 2), and posterior vaginal wall plasty (n = 2). Table 4 includes an overview listing all the characteristics that were compared between the reconstructive surgery and the primary closure group. The group of patients operated on with a reconstructive method (n = 76) significantly included more recurrent tumors: 26.3%, compared to 15.7% in the primary closure group (n = 318) (p = 0.030). Reconstructive surgery was most often used in patients with tumors bigger than 4 cm (p < 0.001), tumors located within 1 cm of the midline (p = 0.013), within 1 cm of the anus (p < 0.001) and 1 cm of the urethra (p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Comparison of primary closure and reconstructive surgery.

3.2.1. Impact of Reconstructive Surgery on Wound Complications

The group that had reconstructive surgery (n = 76) had significantly more complications than primary closure: 55 (72.4%) vs. 129 (40.6%) (n = 318) (p < 0.001) (Table 4). However, the indications for reconstructive surgery included tumors larger than 4cm, perineal-located tumors, and recurrent lesions, which may contribute to the increased complication rate. Wound breakdowns are reported to be significantly less frequent in patients after primary closure, 34.6% (n = 110), compared to after reconstructive surgery, 69.7% (n = 53). Remarkably, the group of patients undergoing reconstructive surgery had significantly fewer wound breakdowns in the category of severe wound breakdowns (those that exceed 50%): 21.8% compared to 28.6% for the primary closure group (p = 0.03). The multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that the group with reconstructive surgery had an increased risk of wound complications OR 1.1 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.1–1.2) compared to the primary closure group (Table 4).

3.2.2. Wound Breakdown Categorized by Size Classification

The incidence of wound breakdowns in smaller tumors (<2 cm) was 39.8%. The reconstructive surgery group showed more wound breakdowns than the primary closure group (63.2% versus 36.7%) (p = 0.027). In 35.3% of reconstructive cases < 2 cm, the tumor was a recurrent tumor. Having previously undergone excision of the primary tumor, the availability of local tissue for closure is significantly reduced at the affected site. For the tumor size group between 2 and 4 cm, wound breakdown incidence was 50.0%. Breakdowns were comparable for primary closure and reconstructive surgery: 47.4% versus 66.7% (p = 0.129). The total incidence of wound breakdowns for more extensive tumors (>4 cm) was 54.3%. In the categorized analyses, a tumor size greater than 4.0 cm in diameter was identified as a risk factor in the univariate analysis (OR 1.9; 95% CI 1.1–3.1) (Table 3). The reconstructive surgery group experienced more wound breakdowns (79.5% versus 36.4%) (p ≤ 0.001). (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of reconstructive and primary closure per tumor size complications.

3.2.3. Impact of Reconstructive Surgery on Resection Margins

In the reconstructive surgery group, 76.3% of patients achieved free tumor margins, with 85.8% achieving comparable results (p = 0.042) in the primary closure group. In the different tumor size groups, the percentage of achieved tumor-free margins decreased gradually with the extension of tumor sizes irrespective of primary or reconstructive closure (Table 6).

Table 6.

Comparison of reconstructive and primary closure per tumor size—free margins.

3.3. Hospitalization and Follow-Up Variables After Vulvar Cancer Surgery

Patients of the reconstructive method group were significantly longer hospitalized with a median of 5 (IQR 3–7) days versus a median of 2 days (IQR 1–4) (p < 0.001; Table 7). Their catheter stayed in longer as well (4 days versus 1 day (p < 0.001)). Re-hospitalization occurred in 52 patients (13.2%); with similar numbers in the reconstructive and the primary group (11 patients (14.5%) versus 41 patients (12.9%)) (p = 0.833). However, patients in the reconstructive closure group were re-hospitalized longer; 8 days (3–22) versus 3 days (1–6) (p = 0.055).

Table 7.

Hospitalization variables and wound complications after primary vulvar surgery.

4. Discussion

In this retrospective multicenter study with a large cohort of 394 patients with vulvar cancer, we report a total of 46.7% of wound complications after surgery for vulvar cancer. Large tumor size, proximity to the urethral, urethra resection, and perineal tumor location were identified as potential contributors to wound complications. In multivariate analysis, reconstructive surgery is associated with a higher risk of wound breakdown. Albeit, this may reflect selection bias, as reconstructive surgery is often preemptively chosen for cases involving larger tumors > 4 cm, perineal-located tumors, and recurrent lesions, which inherently carry higher risks of wound breakdown. Notably, in reconstructive surgery, the wound breakdown tends to be less severe.

The wide variation in reported rates of wound complications in vulvar surgery (9–58%) suggests that there is still some uncertainty regarding their prevalence. According to several articles, tumor size appears to be an essential risk factor for wound complications [15,16,17]. Boyles et al. reported a 42.7% incidence of wound complications in vulvar resections for non-malignant cases, with 39.6% experiencing wound breakdowns and 6.5% developing infections. Risk factors identified for wound complications were larger tumors (OR 1.03; 95% CI 1.01–1.05) and perineal located tumors (OR 2.25; 95% CI 1.38–3.66), which aligns with our findings.

We evaluated several variables as potential risk factors, e.g., smoking, type of suture technique or suture material, mobilization protocols, use of urinary catheter, and others (Appendix A Table A1). The risk factors we identified were larger tumor diameter > 4 cm (OR 1.9; 95% CI 1.1–3.1), <1 cm distance to the anus (OR 3.1; 95% CI 1.7–5.7), resection of the urethra (OR 1.7; 95% CI 1.0–2.8), and perineal location of the tumor (OR 3.2; 95% CI 1.5–6.8). However, after adjusting for confounds, we had no significant risk factors besides RS (OR 1.1; 95% CI 1.1–1.2). Our data indicate that there is no difference in the timing of catheter removal. These risk factors mark important clinical parameters physicians should consider in preparation for vulvar surgery and patient counseling.

The use of reconstructive surgery in vulvar cancer surgery may be beneficial in surgical outcomes for patients with vulvar carcinomas. Panici et al. demonstrated significantly improved outcomes after reconstructive surgery in tumors > 4 cm, with an 11% incidence of wound breakdowns following VY-flaps compared to 40% wound breakdowns with primary closure [27]. In our study, however, we only found wound breakdowns to be less severe after reconstructive surgery. Previous research shows that reconstructive surgery improves clinical outcomes by restoring the anatomy and function of the external genitalia. Reconstructive surgery may therefore aid in improved quality of life [22,23].

Reconstructive surgery is now most often indicated and used in tumors with a larger diameter. In our data set, the median tumor diameter in patients in the reconstructive surgery group is 4.0 cm (range 4.0–5.0 cm) compared to 2.0 cm (range 2.0–2.5 cm) in the primary closure group. Aviki et al. [28] reported similar numbers with an average size of 3.73 cm vs. 2.03 cm, and reconstructive surgery was used more in recurrent cancers or after previous radiotherapy without impact on wound complications. Only previous radiotherapy was associated with wound complications (OR 17) in this study. In our study cohort, previous radiotherapy was an exclusion criterion based on these study data, and we still report high numbers of wound healing disorders. In other studies, however, as published by Weikel et al. [29], no effects in wound healing after radiotherapy were reported as reconstructive surgery was used.

In the Netherlands, reconstructive surgery for vulvar cancer follows local protocols, as the Dutch guidelines provide no specific recommendations for when to use reconstructive surgery [30]. The European Society of Gynaecological Oncology advises including reconstructive skills in multidisciplinary teams. At the same time, the British Gynaecological Cancer Society recommends it for posterior and larger lateral lesions to aid closure and preserve vaginal function [31,32]. Some reports provide algorithms for vulvar reconstruction techniques but need more recommendations on their indications [33]. Multidisciplinary collaboration is vital for providing high-quality care. Considering our data, reconstruction should be considered in larger tumor size, proximity to the urethra, resection of the urethra during surgery, and perineal tumor location. The safety margin recommendations in vulvar cancer vary from margins > 3 mm to those > 8 mm [34,35]. Reconstructive surgery has been reported to facilitate higher complete resection rates [36]. However, our results show that most patients had tumor-free margins, with a significant difference favoring the primary closure group over the reconstructive group.

Limitations of our study are the retrospective nature of the study, the lack of definitions of wound complications used, and the difference in physical follow-up visits in different centers. The lack of standardized wound assessment forms across centers makes for variability in physical follow-up visits, potentially influencing the reported complication rates. The absence of universal definitions for wound complications has been recognized as a recurring challenge, as highlighted in the literature [37]. We have chosen to use the cut-off points according to the percentage of the wound affected. However, in many cases, it proved difficult to place the retrospective data in one of these categories. Muallem et al. previously chose to evaluate wound complications using the Clavien Dindo system. It is a scale that only sometimes reflects the differences and nuances, which is why we have not opted for this classification [38].

In our dataset a selection bias to consult a reconstructive surgeon is present since the gynecologist selects patients where closure on primary intent is impossible based on previous experience. This is important in interpreting the results that show that the use of reconstructive surgery increases the risk of wound complications. The reconstructive surgeons in general are consulted in case of larger tumors, perineal located tumors, and recurrent lesions. These factors are independent of the surgical technique but can influence wound complications. We believe that selection bias does not negatively impact the generalizability of our results. Selection bias is also present in clinical practice, and as such, it provides a good reflection of real-world clinical scenarios.

Despite these limitations, our results provide valuable insights into the high prevalence of wound complications, reflecting current clinical practice in four gynecologic oncology centers in the Netherlands.

Further research is needed to identify effective strategies for the prevention of wound complications. There is some preventive evidence for vacuum-assisted therapy with Prevena/PICO plasters [39]. However, in the urogenital area, application is complex, and evidence in this anatomical area is lacking. To improve outcomes of vulvar cancer surgery, future studies should focus on healthcare evaluation to prospectively evaluate the current practice and the impact of (reconstructive) surgical treatment on health-related patient quality of life, including daily functioning, sexual functioning, and body image.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, larger tumor size, tumor proximity to the urethra, resection of the urethra during surgery, and a perineal tumor location are associated with an increased risk of wound complications after vulvar cancer surgery. RS is associated with high wound complication rates in vulvar cancer and is associated with more extended hospitalization, though this is related to case selection. Based on these data, RS should not be advised in small tumors where primary closure is possible. The indications of reconstructive surgery in vulvar cancer based on these data should be large tumors, when the urethra has to be resected during surgery, or when the tumor is located in proximity to the urethra or perineum. Multidisciplinary collaboration in vulvar cancer surgery is essential to indicate the use of reconstructive surgery.

Author Contributions

J.J.E.D.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing original draft, Validation, Editing, E.E.J.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing original draft, Validation, S.H.: Review, Editing, Statistical Advice, A.v.W.: Review and Editing, D.v.L.: Data curation, D.B.: Review and Editing, B.F.M.S. Review and Editing, R.L.M.B. Review and Editing, P.J.D.V.v.S.: Review and Editing, J.A.d.H.: Review and Editing, A.J.W.M.A.: Review and Editing, E.L.W.G.v.H.: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Review, Editing, E.M.G.v.E.: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Review, Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was exempted from formal ethical assessment, as stated by the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO). The study followed the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Univariate logistic regression analysis for wound complications in patients with vulvar cancer.

Table A1.

Univariate logistic regression analysis for wound complications in patients with vulvar cancer.

| Univariate Logistic Regression | Multivariate Logistic Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR, 95% CI | p-Value | OR, 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Suture technique vulva | 1.065 (0.682–1.661) | 0.783 | 0.495 (0.122–2.007) | 0.325 |

| Suture type vulva | 2.089 (1.040–4.194) | 0.038 | 0.613 (0.104–3.613) | 0.588 |

| Total duration drains | 0.967 (0.909–1.029) | 0.285 | 1.009 (0.942–1.081) | 0.794 |

| Days till mobilization | 0.999 (0.996–1.002) | 0.556 | 0.984 (0.934–1.037) | 0.553 |

| Sitting schedule during hospitalization | 0.279 (0.126–0.614) | 0.002 | 1.730 (0.330–9.067) | 0.517 |

| Reconstructive surgery | 1.183 (1.104–1.267) | <0.001 | 1.299 (1.087–1.551) | 0.004 |

Data are presented as ODDS RATIO, and 95% CI intervals. Every variable was used in the multivariate. Significance < 0.05.

References

- Capria, A.; Tahir, N.; Fatehi, M. Vulva Cancer. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558950/ (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Integraal Kankercentrum Nederland (IKNL). Vulvacarcinoom, Landelijke Richtlijn. 2018. Available online: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/gerelateerde_documenten/f/5532/IKNL%20richtlijn%20Vulvacarcinoom%20(15-01-2018).pdf (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Netherlands Cancer Registry. Available online: https://nkr-cijfers.iknl.nl/viewer/incidentie-per-jaar?language=nl_NL&viewerId=3b55d752-ce1a-4809-89d9-8421febdb1f4 (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Olawaiye, A.B.; Cuello, M.A.; Rogers, L.J. Cancer of the vulva: 2021 update. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 155, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuurman, M.; van den Einden, L.; Massuger, L.; Kiemeney, L.; van der Aa, M.; de Hullu, J. Trends in incidence and survival of Dutch women with vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer 2013, 49, 3872–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellman, K.; Holmberg, E.; Bjurberg, M.; Borgfeldt, C.; Dahm-Kähler, P.; Rådestad, A.F.; Hjerpe, E.; Högberg, T.; Marcickiewicz, J.; Rosenberg, P.; et al. Primary treatment and relative survival by stage and age in vulvar squamous cell carcinoma: A population-based SweGCG study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 159, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinten, F.; Molijn, A.; Eckhardt, L.; Massuger, L.; Quint, W.; Bult, P.; Bulten, J.; Melchers, W.; de Hullu, J. Vulvar cancer: Two pathways with different localization and prognosis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 149, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortekaas, K.E.; Bastiaannet, E.; van Doorn, H.C.; de Vos van Steenwijk, P.J.; Ewing-Graham, P.C.; Creutzberg, C.L.; Akdeniz, K.; Nooij, L.S.; van der Burg, S.H.; Bosse, T.; et al. Vulvar cancer subclassification by HPV and p53 status results in three clinically distinct subtypes. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 159, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, A.T.; Marinoff, S.C.; Christopher, K.; Srodon, M. Prevalence of vulvar lichen sclerosus in a general gynecology practice. J. Reprod. Med. 2005, 50, 477–480. [Google Scholar]

- Gien, L.T.; Slomovitz, B.; Van der Zee, A.; Oonk, M. Phase II activity trial of high-dose radiation and chemosensitization in patients with macrometastatic lymph node spread after sentinel node biopsy in vulvar cancer: GROningen INternational Study on Sentinel nodes in Vulvar cancer III (GROINSS-V III/NRG-GY024). Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2023, 33, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woelber, L.; Griebel, L.-F.; Eulenburg, C.; Sehouli, J.; Jueckstock, J.; Hilpert, F.; de Gregorio, N.; Hasenburg, A.; Ignatov, A.; Hillemanns, P.; et al. Role of tumour-free margin distance for loco-regional control in vulvar cancer—A subset analysis of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynäkologische Onkologie CaRE-1 multicenter study. Eur. J. Cancer 2016, 69, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooij, L.S.; van der Slot, M.A.; Dekkers, O.M.; Stijnen, T.; Gaarenstroom, K.N.; Creutzberg, C.L.; Smit, V.T.H.B.M.; Bosse, T.; Van Poelgeest, M.I.E. Tumour-free margins in vulvar squamous cell carcinoma: Does distance really matter? Eur. J. Cancer 2016, 65, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimond, E.; Delorme, C.; Ouldamer, L.; Carcopino, X.; Bendifallah, S.; Touboul, C.; Daraï, E.; Ballester, M.; Graesslin, O.; FRANCOGYN Research Group. Surgical treatment of vulvar cancer: Impact of tumor-free margin distance on recurrence and survival. A multicentre cohort analysis from the francogyn study group. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 45, 2109–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malandrone, F.; Bevilacqua, F.; Merola, M.; Gallio, N.; Ostacoli, L.; Carletto, S.; Benedetto, C. The impact of vulvar cancer on psychosocial and sexual functioning: A literature review. Cancers 2021, 14, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacalbasa, N.; Balescu, I.; Vilcu, M.; Dima, S.; Brezean, I. Risk factors for postoperative complications after vulvar surgery. Vivo 2019, 34, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senn, B.; Mueller, M.D.; Cignacco, E.L.; Eicher, M. Period prevalence and risk factors for postoperative short-term wound complications in vulvar cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2010, 20, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaarenstroom, K.N.; Kenter, G.G.; Trimbos, J.B.; Agous, I.; Amant, F.; Peters, A.W.; Vergote, I. Postoperative complications after vulvectomy and inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy using separate groin incisions. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2003, 13, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitas, G.; Proppe, L.; Baum, S.; Kruggel, M.; Rody, A.; Tsolakidis, D.; Zouzoulas, D.; Laganà, A.S.; Guenther, V.; Freytag, D.; et al. A risk factor analysis of complications after surgery for vulvar cancer. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 304, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devalia, H.L.; Mansfield, L. Radiotherapy and wound healing. Int. Wound J. 2008, 5, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höckel, M.; Dornhöfer, N. Vulvovaginal reconstruction for neoplastic disease. Lancet Oncol. 2008, 9, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Donato, V.; Bracchi, C.; Cigna, E.; Domenici, L.; Musella, A.; Giannini, A.; Lecce, F.; Marchetti, C.; Panici, P.B. Vulvo-vaginal reconstruction after radical excision for treatment of vulvar cancer: Evaluation of feasibility and morbidity of different surgical techniques. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 26, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiocchi, G.; Rocha, R.M. Vulvar cancer surgery. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 26, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellinga, J.; Rots, M.; Werker, P.M.N.; Stenekes, M.W. Lotus petal flap and vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap in vulvoperineal reconstruction: A systematic review of differences in complications. J. Plast. Surg. Hand Surg. 2020, 55, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confalonieri, P.L.; Gilardi, R.; Rovati, L.C.; Ceccherelli, A.; Lee, J.H.; Magni, S.; Del Bene, M.; Buda, A. Comparison of V-Y advancement flap versus lotus petal flap for plastic reconstruction after surgery in case of vulvar malignancies. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2017, 79, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrelias, T.; Berkane, Y.; Rousson, E.; Uygun, K.; Meunier, B.; Kartheuser, A.; Watier, E.; Duisit, J.; Bertheuil, N. Gluteal propeller perforator flaps: A paradigm shift in abdominoperineal amputation reconstruction. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrão, P.G.; Guimarães, Y.M.; Godoy, L.R.; Possati-Resende, J.C.; Bovo, A.C.; Andrade, C.E.M.C.; Longatto-Filho, A.; dos Reis, R. Management of early-stage vulvar cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panici, P.B.; Di Donato, V.; Bracchi, C.; Marchetti, C.; Tomao, F.; Palaia, I.; Perniola, G.; Muzii, L. Modified gluteal fold advancement V-Y flap for vulvar reconstruction after surgery for vulvar malignancies. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 132, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviki, E.M.; Esselen, K.M.; Barcia, S.M.; Nucci, M.R.; Horowitz, N.S.; Feltmate, C.M.; Berkowitz, R.S.; Orgill, D.G.; Viswanathan, A.N.; Muto, M.G. Does plastic surgical consultation improve the outcome of patients undergoing radical vulvectomy for squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva? Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 137, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weikel, W.; Hofmann, M.; Steiner, E.; Knapstein, P.; Koelbl, H. Reconstructive surgery following resection of primary vulvar cancers. Gynecol. Oncol. 2005, 99, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NVOG. Richtlijnen Database Vulvacarcinoom. 2 May 2011. Available online: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/vulvacarcinoom/algemeen.html (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO). Vulvar Cancer Guidelines. 2023. Available online: https://guidelines.esgo.org/vulvar-cancer/guidelines/recommendations/ (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Morrison, J.; Baldwin, P.; Buckley, L.; Cogswell, L.; Edey, K.; Faruqi, A.; Ganesan, R.; Hall, M.; Hillaby, K.; Reed, N.; et al. British Gynaecological Cancer Society (BGCS) vulval cancer guidelines: Recommendations for practice. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 252, 502–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentileschi, S.; Servillo, M.; Garganese, G.; Fragomeni, S.; De Bonis, F.; Scambia, G.; Salgarello, M. Surgical therapy of vulvar cancer: How to choose the correct reconstruction? J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 27, e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, E.L.; Jackson, M.; Hacker, N.F. The prognostic role of the surgical margins in squamous vulvar cancer: A retrospective Australian study. Cancers 2020, 12, 3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootenhuis, N.T.; Pouwer, A.; de Bock, G.; Hollema, H.; Bulten, J.; van der Zee, A.; de Hullu, J.; Oonk, M. Margin status revisited in vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019, 154, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muallem, M.Z.; Sehouli, J.; Miranda, A.; Plett, H.; Sayasneh, A.; Diab, Y.; Muallem, J.; Hatoum, I. Reconstructive surgery versus primary closure following vulvar cancer excision: A wide single-center experience. Cancers 2022, 14, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strasberg, S.M.; Linehan, D.C.; Hawkins, W.G. The Accordion Severity Grading System of Surgical Complications. Ann. Surg. 2009, 250, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, P.D.; Chalasani, V.; Woo, H.H. Use of Clavien-Dindo classification in reporting and grading complications after urological surgical procedures: Analysis of 2010 to 2012. J. Urol. 2013, 190, 1271–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedi, M.; King, D.M.; DeVries, J.; Hackbarth, D.A.; Neilson, J.C. Does vacuum-assisted closure reduce the risk of wound complications in patients with lower extremity sarcomas treated with preoperative radiation? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2019, 477, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).