Synergistic Strategies for KMT2A-Rearranged Leukemias: Beyond Menin Inhibitor

Simple Summary

Abstract

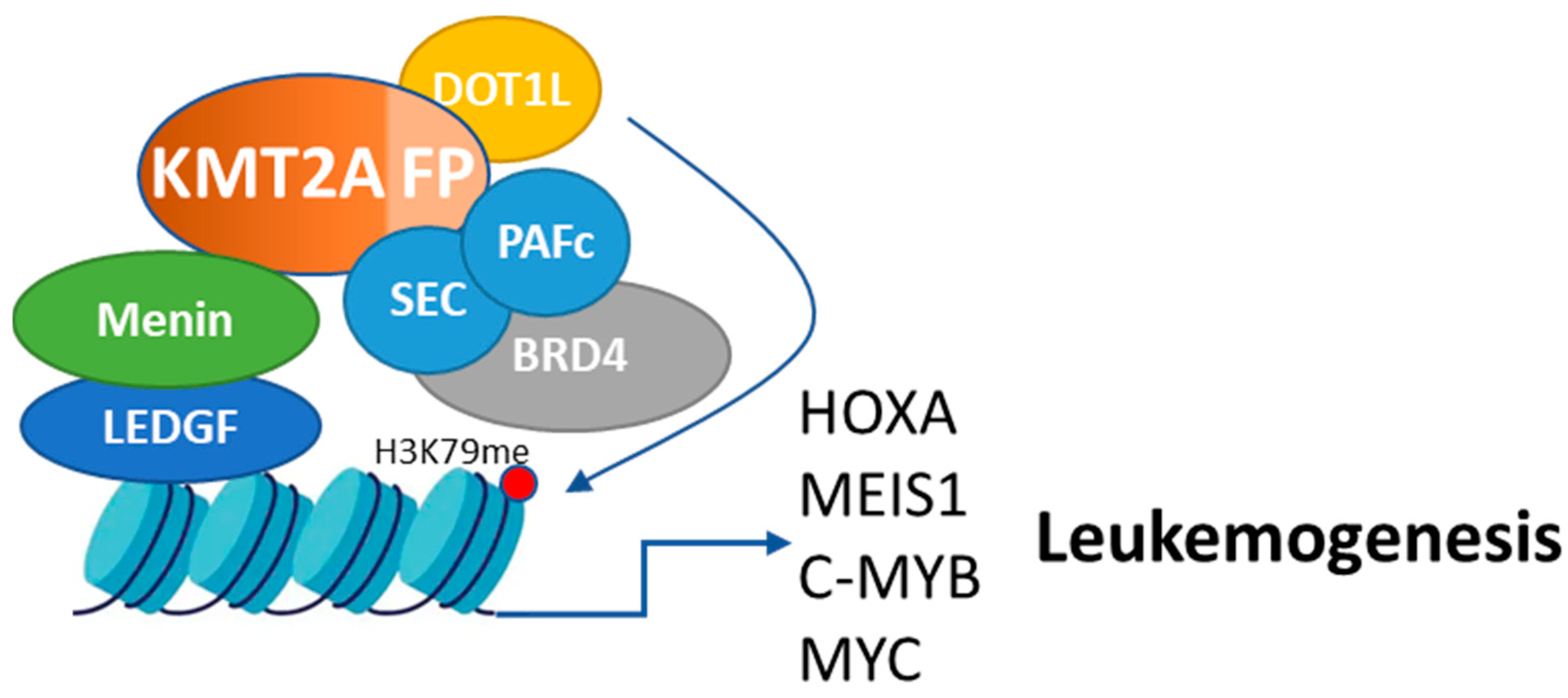

1. Introduction

2. Mechanism of Action and Efficacy of Menin Inhibitors

3. Clinical Development of Menin Inhibitors

- Revumenib (SNDX-5613): The AUGMENT-101 trial (NCT04065399) evaluated revumenib in a phase I/II study involving patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) acute leukemia harboring KMT2A rearrangements or NPM1 mutations. The interim analysis demonstrated clinical activity, with 24% of KMT2Ar AML patients achieving complete remission (CR) or CR with partial hematologic recovery (CRh) [22]. Menin mutations as a resistance mechanism were also noted, emphasizing the need for continued monitoring and combination strategies [22,23].

- Ziftomenib (KO-539): The KOMET-001 trial (NCT04067336) investigated ziftomenib in patients with R/R AML. Early reports indicated a higher response rate in NPM1-mutated AML compared with KMT2Ar AML, with CR rates of 35% and 5.6%, respectively [24,25]. This differential response suggests a possible shift in the trial’s focus toward NPM1-mutated AML patients in subsequent phases.

- DSP-5336: The ongoing phase I/II trial (NCT04988555) explores DSP-5336 in adult patients with R/R AML and ALL, specifically targeting those with KMT2Ar and NPM1 mutations. Early data indicate significant variance in efficacy, with the CR and CRh rate reaching 44% in the NPM1mt group, compared to only 8% in the KMT2Ar cohort [26]. These findings highlight a potentially greater benefit of DSP-5336 in patients with NPM1 mutations, guiding further investigation and clinical application in this subgroup.

- Bleximenib: The ongoing phase I/II trial (NCT04811560) is evaluating bleximenib (formerly known as JNJ-75276617), a menin–KMT2A inhibitor, in patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) acute leukemia with KMT2A or NPM1 alterations. As of April 2023, 58 patients were treated, with an overall response rate (ORR) of 50% at the highest dose level (90 mg BID), including complete remissions [27]. Common treatment-related adverse events included differentiation syndrome and cytopenias. Preliminary biomarker data showed reductions in menin–KMT2A target genes, including MEIS1, HOXA9, and FLT3, as well as the induction of genes associated with differentiation, such as ITGAM and MNDA. Dose escalation continues to determine the recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D).

- DS-1594: In the phase I/II trial (NCT04752163), DS-1594 is being studied both as a monotherapy and in combination with azacytidine and venetoclax or mini-HCVD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, dexamethasone). Preclinical data suggested efficacy, but clinical results are awaited.

- BMF-219: The COVALENT-101 trial (NCT05153330) is a phase I study investigating BMF-219, a covalent menin inhibitor, in patients with AML, ALL, multiple myeloma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Initial findings reported complete remission in two out of five AML patients, with no dose-limiting toxicities observed.

Combination Trials of Menin Inhibitors in AML

4. Resistance Mechanisms to Menin Inhibitors

4.1. Genetic Resistance Mechanisms

4.2. Epigenetic and Alternative Resistance Mechanisms

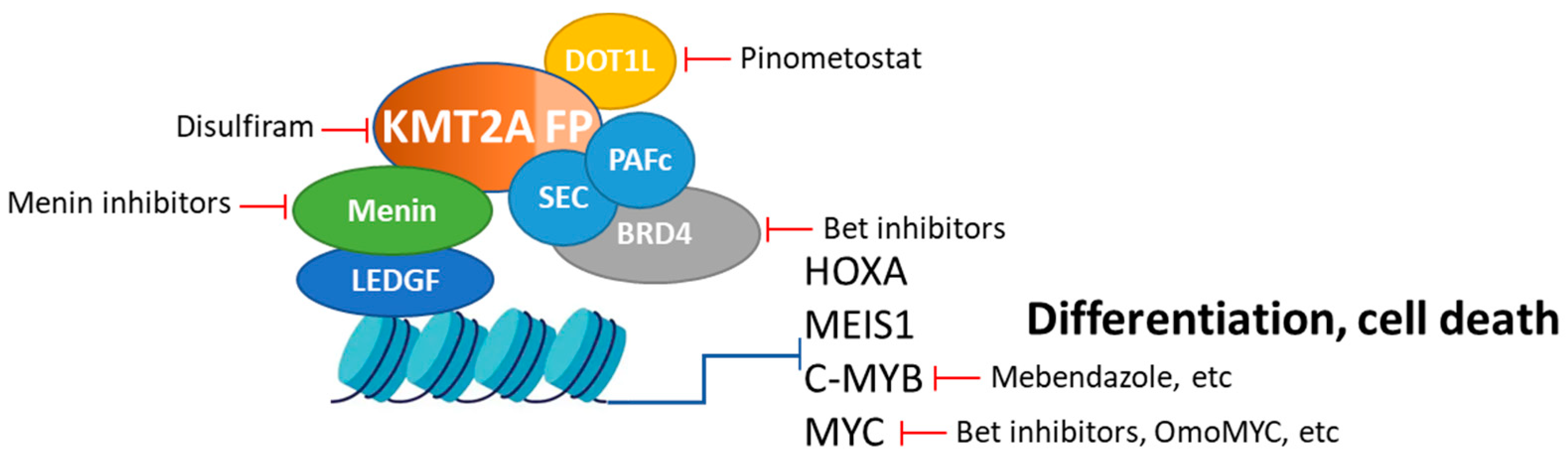

5. Alternative and Synergistic Therapeutic Strategies

5.1. Targeting DOT1L: Role, Strategies of Inhibition, and Potential Synergy with Menin Inhibitors

5.1.1. The Role of DOT1L in KMT2Ar Leukemias

5.1.2. Strategies for Inhibiting DOT1L

5.1.3. Potential Synergy with Menin Inhibitors

5.2. Targeting BRD4: Role, Strategies of Inhibition, and Potential Synergy with Menin Inhibitors

5.2.1. The Role of BRD4 in KMT2Ar Leukemias

5.2.2. Strategies for Inhibiting BRD4

5.2.3. Potential Synergy with Menin Inhibitors

5.3. Direct Targeting of KMT2A-Fusion Proteins: Role, Strategies of Inhibition, and Potential Synergy with Menin Inhibitors

5.3.1. The Role of KMT2A-Fusion Proteins in Leukemogenesis

5.3.2. Strategies for Direct Inhibition of KMT2A-Fusion Proteins

5.3.3. Potential Synergy with Menin Inhibitors

5.4. MYC Inhibition: Role, Strategies of Inhibition, and Potential Synergy with Menin Inhibitors

5.4.1. The Role of MYC in KMT2Ar Leukemias

5.4.2. Strategies for Direct Inhibition MYC

5.4.3. Potential Synergy with Menin Inhibitors

5.5. Targeting c-MYB: Role, Strategies of Inhibition, and Potential Synergy with Menin Inhibitors

5.5.1. The Role of c-MYB in KMT2Ar Leukemias

5.5.2. Strategies for Inhibiting c-MYB

5.5.3. Potential Synergy with Menin Inhibitors

5.6. Targeting Chromatin Remodeling: Role, Strategies of Inhibition, and Potential Synergy with Menin Inhibitors

5.6.1. The Role of Chromatin Remodeling Complexes in Leukemogenesis

5.6.2. Strategies for Inhibiting Chromatin Remodeling Complexes

5.6.3. Potential Synergy with Menin Inhibitors

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van Weelderen, R.E.; Klein, K.; Harrison, C.J.; Jiang, Y.; Abrahamsson, J.; Arad-Cohen, N.; Bart-Delabesse, E.; Buldini, B.; De Moerloose, B.; Dworzak, M.N.; et al. Measurable Residual Disease and Fusion Partner Independently Predict Survival and Relapse Risk in Childhood KMT2A-Rearranged Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Study by the International Berlin-Frankfurt-Munster Study Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 2963–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issa, G.C.; Zarka, J.; Sasaki, K.; Qiao, W.; Pak, D.; Ning, J.; Short, N.J.; Haddad, F.; Tang, Z.; Patel, K.P.; et al. Predictors of outcomes in adults with acute myeloid leukemia and KMT2A rearrangements. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollard, J.A.; Guest, E.; Alonzo, T.A.; Gerbing, R.B.; Loken, M.R.; Brodersen, L.E.; Kolb, E.A.; Aplenc, R.; Meshinchi, S.; Raimondi, S.C.; et al. Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin Improves Event-Free Survival and Reduces Relapse in Pediatric KMT2A-Rearranged AML: Results from the Phase III Children’s Oncology Group Trial AAML0531. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 3149–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, S.A.; Staunton, J.E.; Silverman, L.B.; Pieters, R.; den Boer, M.L.; Minden, M.D.; Sallan, S.E.; Lander, E.S.; Golub, T.R.; Korsmeyer, S.J. MLL translocations specify a distinct gene expression profile that distinguishes a unique leukemia. Nat. Genet. 2002, 30, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winters, A.C.; Bernt, K.M. MLL-Rearranged Leukemias-An Update on Science and Clinical Approaches. Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pui, C.H.; Chessells, J.M.; Camitta, B.; Baruchel, A.; Biondi, A.; Boyett, J.M.; Carroll, A.; Eden, O.B.; Evans, W.E.; Gadner, H.; et al. Clinical heterogeneity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia with 11q23 rearrangements. Leukemia 2003, 17, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pui, C.H.; Gaynon, P.S.; Boyett, J.M.; Chessells, J.M.; Baruchel, A.; Kamps, W.; Silverman, L.B.; Biondi, A.; Harms, D.O.; Vilmer, E.; et al. Outcome of treatment in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia with rearrangements of the 11q23 chromosomal region. Lancet 2002, 359, 1909–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saultz, J.N.; Garzon, R. Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Concise Review. J. Clin. Med. 2016, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.; Larghero, P.; Almeida Lopes, B.; Burmeister, T.; Groger, D.; Sutton, R.; Venn, N.C.; Cazzaniga, G.; Corral Abascal, L.; Tsaur, G.; et al. The KMT2A recombinome of acute leukemias in 2023. Leukemia 2023, 37, 988–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkin, D.; He, S.; Miao, H.; Kempinska, K.; Pollock, J.; Chase, J.; Purohit, T.; Malik, B.; Zhao, T.; Wang, J.; et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of the Menin-MLL interaction blocks progression of MLL leukemia in vivo. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klossowski, S.; Miao, H.; Kempinska, K.; Wu, T.; Purohit, T.; Kim, E.; Linhares, B.M.; Chen, D.; Jih, G.; Perkey, E.; et al. Menin inhibitor MI-3454 induces remission in MLL1-rearranged and NPM1-mutated models of leukemia. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 981–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krivtsov, A.V.; Evans, K.; Gadrey, J.Y.; Eschle, B.K.; Hatton, C.; Uckelmann, H.J.; Ross, K.N.; Perner, F.; Olsen, S.N.; Pritchard, T.; et al. A Menin-MLL Inhibitor Induces Specific Chromatin Changes and Eradicates Disease in Models of MLL-Rearranged Leukemia. Cancer Cell 2019, 36, 660–673 e611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoyama, A.; Somervaille, T.C.; Smith, K.S.; Rozenblatt-Rosen, O.; Meyerson, M.; Cleary, M.L. The menin tumor suppressor protein is an essential oncogenic cofactor for MLL-associated leukemogenesis. Cell 2005, 123, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohner, H.; Wei, A.H.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Craddock, C.; DiNardo, C.D.; Dombret, H.; Ebert, B.L.; Fenaux, P.; Godley, L.A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood 2022, 140, 1345–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issa, G.C.; Bidikian, A.; Venugopal, S.; Konopleva, M.; DiNardo, C.D.; Kadia, T.M.; Borthakur, G.; Jabbour, E.; Pemmaraju, N.; Yilmaz, M.; et al. Clinical outcomes associated with NPM1 mutations in patients with relapsed or refractory AML. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travaglini, S.; Gurnari, C.; Ottone, T.; Voso, M.T. Advances in the pathogenesis of FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia and targeted treatments. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2024, 36, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, A.; Zarychta, J.; Lejman, M.; Latoch, E.; Zawitkowska, J. Clinical Implications of Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Mutations and Targeted Treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukemia with Mutant Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Inhibitors-Recent Advances, Challenges and Future Prospects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahswar, R.; Ganser, A. Relapse and resistance in acute myeloid leukemia post venetoclax: Improving second lines therapy and combinations. Expert. Rev. Hematol. 2024, 17, 723–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, A.; Cleary, M.L. Menin critically links MLL proteins with LEDGF on cancer-associated target genes. Cancer Cell 2008, 14, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Q.D.; Fan, D.; Han, Q.; Liu, Y.; Miao, H.; Wang, X.; Li, Q.; Chen, D.; Gore, H.; Himadewi, P.; et al. Mutant NPM1 Hijacks Transcriptional Hubs to Maintain Pathogenic Gene Programs in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2023, 13, 724–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uckelmann, H.J.; Haarer, E.L.; Takeda, R.; Wong, E.M.; Hatton, C.; Marinaccio, C.; Perner, F.; Rajput, M.; Antonissen, N.J.C.; Wen, Y.; et al. Mutant NPM1 Directly Regulates Oncogenic Transcription in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2023, 13, 746–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issa, G.C.; Aldoss, I.; Thirman, M.J.; DiPersio, J.; Arellano, M.; Blachly, J.S.; Mannis, G.N.; Perl, A.; Dickens, D.S.; McMahon, C.M.; et al. Menin Inhibition with Revumenib for KMT2A-Rearranged Relapsed or Refractory Acute Leukemia (AUGMENT-101). J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, JCO2400826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perner, F.; Stein, E.M.; Wenge, D.V.; Singh, S.; Kim, J.; Apazidis, A.; Rahnamoun, H.; Anand, D.; Marinaccio, C.; Hatton, C.; et al. MEN1 mutations mediate clinical resistance to menin inhibition. Nature 2023, 615, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erba, H.; Wang, E.; Issa, G.; Altman, J.; Montesinos, P.; DeBotton, S.; Walter, R.; Pettit, K.; Strickland, S.; Patnaik, M.; et al. Activity, Tolerability, and Resistance Profile of the Menin Inhibitor Ziftomenib in Adults with Relapsed/Refractory NPM1-Mutated AML. Cl. Lymph. Myelom Leuk. 2023, 23, S304–S305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erba, H.P.; Fathi, A.T.; Issa, G.C.; Altman, J.K.; Montesinos, P.; Patnaik, M.M.; Foran, J.M.; De Botton, S.; Baer, M.R.; Schiller, G.J.; et al. Update on a Phase 1/2 First-in-Human Study of the Menin-KMT2A (MLL) Inhibitor Ziftomenib (KO-539) in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2022, 140 (Suppl. S1), 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daver, N.; Erba, H.P.; Watts, J.M.; Yuda, J.; Wang, E.S.; Brandwein, J.; Shima, T.; Palmisiano, N.; Borate, U.; Miyazaki, Y.; et al. First-in-Human Phase 1/2 Study of the Menin- MLL Inhibitor DSP-5336 in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Acute Leukemia: Updared Results from Dose Escalation. HemaSphere 2024, 8, 72–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, E.; Searle, E.; Abdul-Hay, M.; Abedin, S.; Aldoss, I.; Piérola, A.A.; Alonso-Dominguez, J.M.; Chevallier, P.; Cost, C.; Daskalakis, N.; et al. A First-in-Human Phase 1 Study of the Menin-KMT2A (MLL1) Inhibitor JNJ-75276617 in Adult Patients with Relapsed/Refractory Acute Leukemia Harboring KMT2A or NPM1 Alterations. Blood 2023, 142, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, A.; Wang, E.; Issa, G.; Erba, H.; Altman, J.; Balasubramanian, S.; Strickland, S.; Roboz, G.; Schiller, G.; McMahon, C.; et al. Ziftomenib Combined with Intensive Induction (7 + 3) in Newly Diagnosed NPM1-m or KMT2A-r Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Interim Phase 1a Results from KOMET-007. Available online: https://ash.confex.com/ash/2024/webprogram/Paper198218.html (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Recher, C.; O’Nions, J.; Aldoss, I.; Alfonso Pierola, A.; Allred, A.; Alonso-Dominguez, J.; Barreyro, L.; Bories, P.; Curtis, M.; Daskalakis, N.; et al. Phase 1b Study of Menin-KMT2A Inhibitor Bleximenib in Combination with Intensive Chemotherapy in Newly Diagnosed Acute Myeloid Leukemia with KMT2Ar or NPM1 Alterations. Available online: https://ash.confex.com/ash/2024/webprogram/Paper207072.html (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Salzer, E.; Stutterheim, J.; Cuglievan, B.; Tomkinson, B.; Leoni, M.; Van Tinteren, H.; Huitema, A.; Willemse, M.; Nichols, G.; Bautista, F.; et al. APAL2020K/ITCC-101: A Phase I Trial of the Menin Inhibitor Ziftomenib in Combination with Chemotherapy in Children with Relapsed/Refractory KMT2A-Rearranged, NUP98-Rearranged, or NPM1-Mutant Acute Leukemias. Available online: https://ash.confex.com/ash/2024/webprogram/Paper204583.html (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Issa, G.; Cuglievan, B.; Daver, N.; DiNardo, C.; Farhat, A.; Short, N.; McCall, D.; Pike, A.; Tan, S.; Kammerer, B.; et al. Phase I/II Study of the All-Oral Combination of Revumenib (SNDX-5613) with Decitabine/Cedazuridine (ASTX727) and Venetoclax (SAVE) in R/R AML. Available online: https://ash.confex.com/ash/2024/webprogram/Paper204375.html (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Fathi, A.; Issa, G.; Wang, E.; Erba, H.; Altman, J.; Balasubramanian, S.; Roboz, G.; Schiller, G.; McMahon, C.; Palmisiano, N.; et al. Ziftomenib Combined with Venetoclax/Azacitidine in Relapsed/Refractory NPM1-m or KMT2A-r Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Interim Phase 1a Results from KOMET-007. Available online: https://ash.confex.com/ash/2024/webprogram/Paper199170.html (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Daver, N.; Lee, K.; Choi, Y.; Montesinos, P.; Jonas, B.; Arellano, M.; Borate, U.; Watts, J.; Koller, P.; Jung, C.; et al. Phase 1 Safety and Efficacy of Tuspetinib Plus Venetoclax Combination Therapy in Study Participants with Relapsed or Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML). Available online: https://ash.confex.com/ash/2023/webprogram/Paper182296.html (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Hyrenius-Wittsten, A.; Pilheden, M.; Sturesson, H.; Hansson, J.; Walsh, M.P.; Song, G.; Kazi, J.U.; Liu, J.; Ramakrishan, R.; Garcia-Ruiz, C.; et al. De novo activating mutations drive clonal evolution and enhance clonal fitness in KMT2A-rearranged leukemia. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Feliciano, Y.M.; Sanchez-Rivera, F.J.; Perner, F.; Barrows, D.W.; Kastenhuber, E.R.; Ho, Y.J.; Carroll, T.; Xiong, Y.; Anand, D.; Soshnev, A.A.; et al. A Molecular Switch between Mammalian MLL Complexes Dictates Response to Menin-MLL Inhibition. Cancer Discov. 2023, 13, 146–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, D.H.; Duran, M.; Otto, D.J.; Kirkey, D.; Yi, J.S.; Meshinchi, S.; Sarthy, J.F.; Ahmad, K.; Henikoff, S. KMT2A oncoproteins induce epigenetic resistance to targeted therapies. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perner, F.; Rahnamoun, H.; Wenge, D.V.; Xiong, Y.; Apazidis, A.; Anand, D.; Hatton, C.; Wen, Y.; Gu, S.; Liu, X.S.; et al. Non-Genetic Resistance to Menin Inhibtion in AML is Reversible by Pertubation of KAT6A. HemaSphere 2023, 7, e6233123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, M.; Bechwar, J.; Voigtlander, D.; Fischer, M.; Schnetzke, U.; Hochhaus, A.; Scholl, S. Synergistic Effects of the RARalpha Agonist Tamibarotene and the Menin Inhibitor Revumenib in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells with KMT2A Rearrangement or NPM1 Mutation. Cancers 2024, 16, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.Y.; Zhang, L.X.; Aryal, S.; Moreira, S.; Veasey, V.; Hope, K.J.; Lu, R. Decoding the Epigenetic Drivers of Menin-MLL Inhibitor Resistance in KMT2A-Rearranged Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2023, 142, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, L.; Aryal, S.; Veasey, V.; Tajik, A.; Restelli, C.; Moreira, S.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Hope, K.; et al. Epigenetic Regulation of Non-canonical Menin Targets Modulates Menin Inhibitor Response in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2024, 144, 2018–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavallee, V.P.; Baccelli, I.; Krosl, J.; Wilhelm, B.; Barabe, F.; Gendron, P.; Boucher, G.; Lemieux, S.; Marinier, A.; Meloche, S.; et al. The transcriptomic landscape and directed chemical interrogation of MLL-rearranged acute myeloid leukemias. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, E.M.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Rizzieri, D.A.; Tibes, R.; Berdeja, J.G.; Savona, M.R.; Jongen-Lavrenic, M.; Altman, J.K.; Thomson, B.; Blakemore, S.J.; et al. The DOT1L inhibitor pinometostat reduces H3K79 methylation and has modest clinical activity in adult acute leukemia. Blood 2018, 131, 2661–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafflon, C.; Craig, V.J.; Mereau, H.; Grasel, J.; Schacher Engstler, B.; Hoffman, G.; Nigsch, F.; Gaulis, S.; Barys, L.; Ito, M.; et al. Complementary activities of DOT1L and Menin inhibitors in MLL-rearranged leukemia. Leukemia 2017, 31, 1269–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriaanse, F.R.S.; Schneider, P.; Arentsen-Peters, S.; Fonseca, A.; Stutterheim, J.; Pieters, R.; Zwaan, C.M.; Stam, R.W. Distinct Responses to Menin Inhibition and Synergy with DOT1L Inhibition in KMT2A-Rearranged Acute Lymphoblastic and Myeloid Leukemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiskus, W.; Mill, C.P.; Birdwell, C.; Davis, J.A.; Das, K.; Boettcher, S.; Kadia, T.M.; DiNardo, C.D.; Takahashi, K.; Loghavi, S.; et al. Targeting of epigenetic co-dependencies enhances anti-AML efficacy of Menin inhibitor in AML with MLL1-r or mutant NPM1. Blood Cancer J. 2023, 13, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Vakoc, C.R. The mechanisms behind the therapeutic activity of BET bromodomain inhibition. Mol. Cell 2014, 54, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.Y.; Chiang, C.M. The double bromodomain-containing chromatin adaptor Brd4 and transcriptional regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 13141–13145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, M.A.; Prinjha, R.K.; Dittmann, A.; Giotopoulos, G.; Bantscheff, M.; Chan, W.I.; Robson, S.C.; Chung, C.W.; Hopf, C.; Savitski, M.M.; et al. Inhibition of BET recruitment to chromatin as an effective treatment for MLL-fusion leukaemia. Nature 2011, 478, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roe, J.S.; Mercan, F.; Rivera, K.; Pappin, D.J.; Vakoc, C.R. BET Bromodomain Inhibition Suppresses the Function of Hematopoietic Transcription Factors in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Mol. Cell 2015, 58, 1028–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsa, M.; Xiao, L.; Ronca, E.; Bongers, A.; Spurling, D.; Karsa, A.; Cantilena, S.; Mariana, A.; Failes, T.W.; Arndt, G.M.; et al. FDA-approved disulfiram as a novel treatment for aggressive leukemia. J. Mol. Med. 2024, 102, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantilena, S.; Gasparoli, L.; Pal, D.; Heidenreich, O.; Klusmann, J.H.; Martens, J.H.A.; Faille, A.; Warren, A.J.; Karsa, M.; Pandher, R.; et al. Direct targeted therapy for MLL-fusion-driven high-risk acute leukaemias. Clin. Transl. Med. 2022, 12, e933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, U.; Lo-Coco, F. Targeting of leukemia-initiating cells in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Stem Cell Investig. 2015, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Chen, S.J.; Tong, J.H.; Wang, Z.G.; Chen, G.Q.; Chen, Z. Treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with ATRA and As2O3: A model of molecular target-based cancer therapy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2002, 1, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rerolle, D.; Wu, H.C.; de The, H. Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia, Retinoic Acid, and Arsenic: A Tale of Dualities. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2024, 14, a041582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castell, A.; Yan, Q.; Fawkner, K.; Hydbring, P.; Zhang, F.; Verschut, V.; Franco, M.; Zakaria, S.M.; Bazzar, W.; Goodwin, J.; et al. A selective high affinity MYC-binding compound inhibits MYC:MAX interaction and MYC-dependent tumor cell proliferation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Wang, P.; Yang, L.; Wu, Z.; Li, S.; Xu, Y.; Wu, B.; Ma, A.; Gan, X.; Xu, R. Novel synthetic tosyl chloride-berbamine regresses lethal MYC-positive leukemia by targeting CaMKIIgamma/Myc axis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 117, 109134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garralda, E.; Beaulieu, M.E.; Moreno, V.; Casacuberta-Serra, S.; Martinez-Martin, S.; Foradada, L.; Alonso, G.; Masso-Valles, D.; Lopez-Estevez, S.; Jauset, T.; et al. MYC targeting by OMO-103 in solid tumors: A phase 1 trial. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walf-Vorderwulbecke, V.; Pearce, K.; Brooks, T.; Hubank, M.; van den Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M.; Zwaan, C.M.; Adams, S.; Edwards, D.; Bartram, J.; Samarasinghe, S.; et al. Targeting acute myeloid leukemia by drug-induced c-MYB degradation. Leukemia 2018, 32, 882–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, T.J.; Klempnauer, K.H. Natural Products with Antitumor Potential Targeting the MYB-C/EBPbeta-p300 Transcription Module. Molecules 2022, 27, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takao, S.; Forbes, L.; Uni, M.; Cheng, S.; Pineda, J.M.B.; Tarumoto, Y.; Cifani, P.; Minuesa, G.; Chen, C.; Kharas, M.G.; et al. Convergent organization of aberrant MYB complex controls oncogenic gene expression in acute myeloid leukemia. eLife 2021, 10, e65905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiskus, W.; Piel, J.; Collins, M.; Hentemann, M.; Cuglievan, B.; Mill, C.P.; Birdwell, C.E.; Das, K.; Davis, J.A.; Hou, H.; et al. BRG1/BRM inhibitor targets AML stem cells and exerts superior preclinical efficacy combined with BET or menin inhibitor. Blood 2024, 143, 2059–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Ding, Y.; Huang, W.; Guo, N.; Ren, Q.; Wang, N.; Ma, X. Synergistic effects of the KDM4C inhibitor SD70 and the menin inhibitor MI-503 against MLL::AF9-driven acute myeloid leukaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2024, 205, 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cantilena, S.; AlAmeri, M.; Che, N.; Williams, O.; de Boer, J. Synergistic Strategies for KMT2A-Rearranged Leukemias: Beyond Menin Inhibitor. Cancers 2024, 16, 4017. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16234017

Cantilena S, AlAmeri M, Che N, Williams O, de Boer J. Synergistic Strategies for KMT2A-Rearranged Leukemias: Beyond Menin Inhibitor. Cancers. 2024; 16(23):4017. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16234017

Chicago/Turabian StyleCantilena, Sandra, Mohamed AlAmeri, Noelia Che, Owen Williams, and Jasper de Boer. 2024. "Synergistic Strategies for KMT2A-Rearranged Leukemias: Beyond Menin Inhibitor" Cancers 16, no. 23: 4017. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16234017

APA StyleCantilena, S., AlAmeri, M., Che, N., Williams, O., & de Boer, J. (2024). Synergistic Strategies for KMT2A-Rearranged Leukemias: Beyond Menin Inhibitor. Cancers, 16(23), 4017. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16234017