Enhancing Patient Experience in Sarcoma Core Biopsies: The Role of Communication, Anxiety Management, and Pain Control

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Anatomical Regions:

- Axial Regions: Includes the head and neck, trunk, and visceral regions (further divided into intraperitoneal and retroperitoneal).

- Appendicular Regions: Encompasses the upper extremities and lower extremities.

- Tissue of Origin:

- Superficial Soft Tissue (SST): Tumors originating in tissues close to the skin or epifascial.

- Deep Soft Tissue (DST): Tumors originating in deeper tissues, such as muscles or below the superficial fascia.

- Bone: Tumors originating from or within bone structures.

2.1. Creating the IPA Questionnaire for Detailed PREM and PROM Evaluation

- Questions composing the questionnaire:

- Q1: Did you understand the reason and necessity for the procedure?

- 1 (not at all understood)—10 (fully understood)

- Q2: Was the procedure well explained by the physician who performed it?

- 1 (not at all explained)—10 (very well explained)

- Q3: How well did you understand what was done during the procedure?

- 1 (not at all understood)—10 (perfectly understood)

- Q4: How strong was your fear from the procedure?

- 1 (strongest fear ever experienced)—10 (no fear)

- Q5: Consider the entire procedure, did you feel comfortable with the team and the room set-up?

- 1 (not at all comfortable)—10 (very comfortable)

- Q6: How would you rate the entire organization process of the procedure?

- 1 (not at all good)—10 (very good)

- Q7: How badly did you feel the pain during the procedure?

- 1 (strongest pain ever experienced)—10 (no pain)

- Q8: Did the pain experienced during the procedure match your expectation?

- 1 (not at all matched)—10 (perfectly matched)

- Q9: How satisfied were you with the medication you received during the procedure?

- 1 (not at all satisfied)—10 (very satisfied)

- Q10: Was the pain well controlled during the first 24–48 h after the procedure?

- 1 (not at all controlled)—10 (very well controlled)

- Q11: Was the observation period after the procedure long enough until dismissal?

- 1 (it was not long enough, I felt stressed)—10 (it was long enough, I did not feel stressed at all)

- Q12: Was there any bleeding after the procedure?

- 1 (heavy bleeding)—10 (no bleeding)

- Q13: Did you experience other local problems after the procedure (hematoma, redness, infection, swelling, other)?

- 1 (many other problems)—10 (no problems)

2.2. Data Analyses

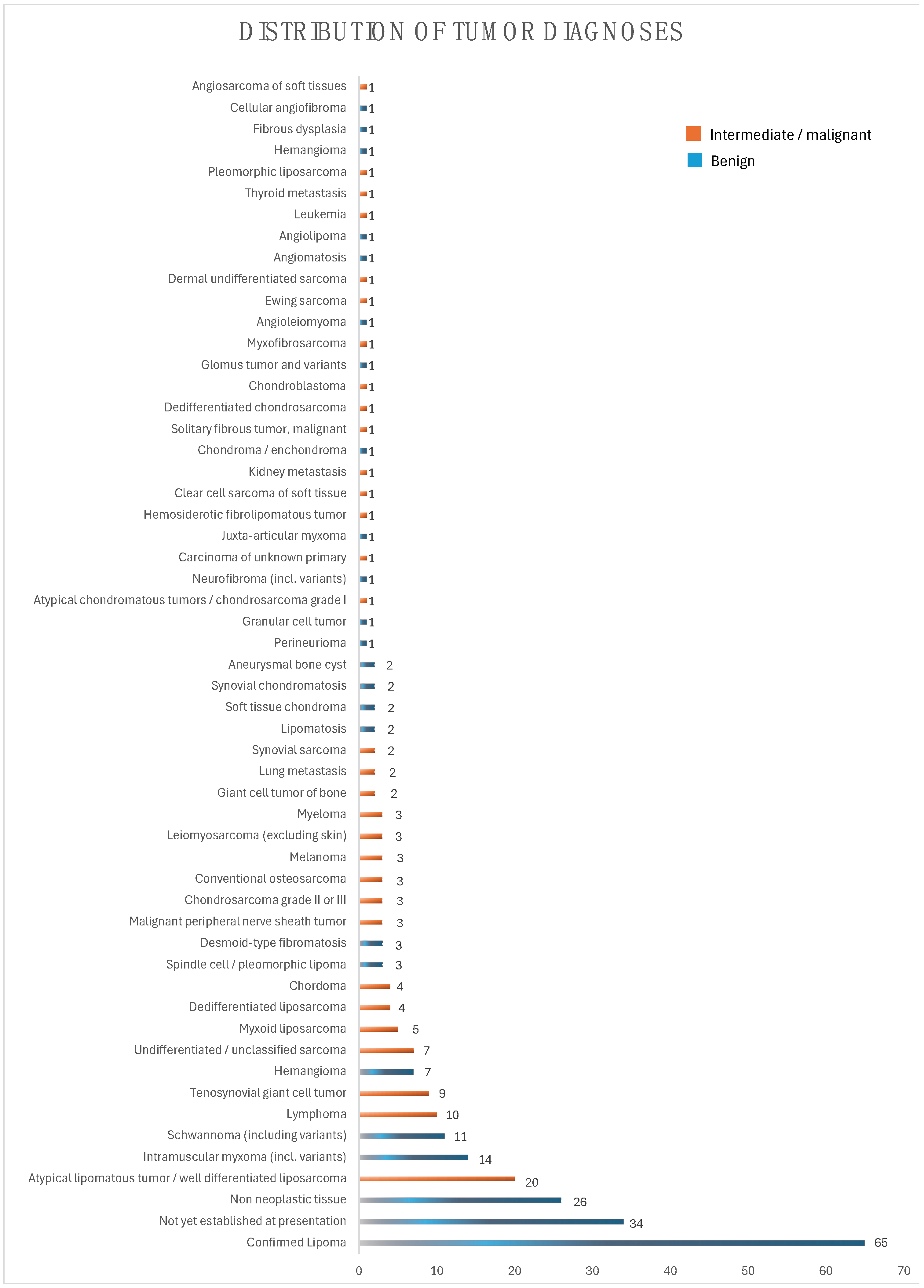

3. Results

3.1. Differences Depending on Gender, Anatomic Region of the Tumor, Origin of Lesion, and Biological Behavior of the Tumor

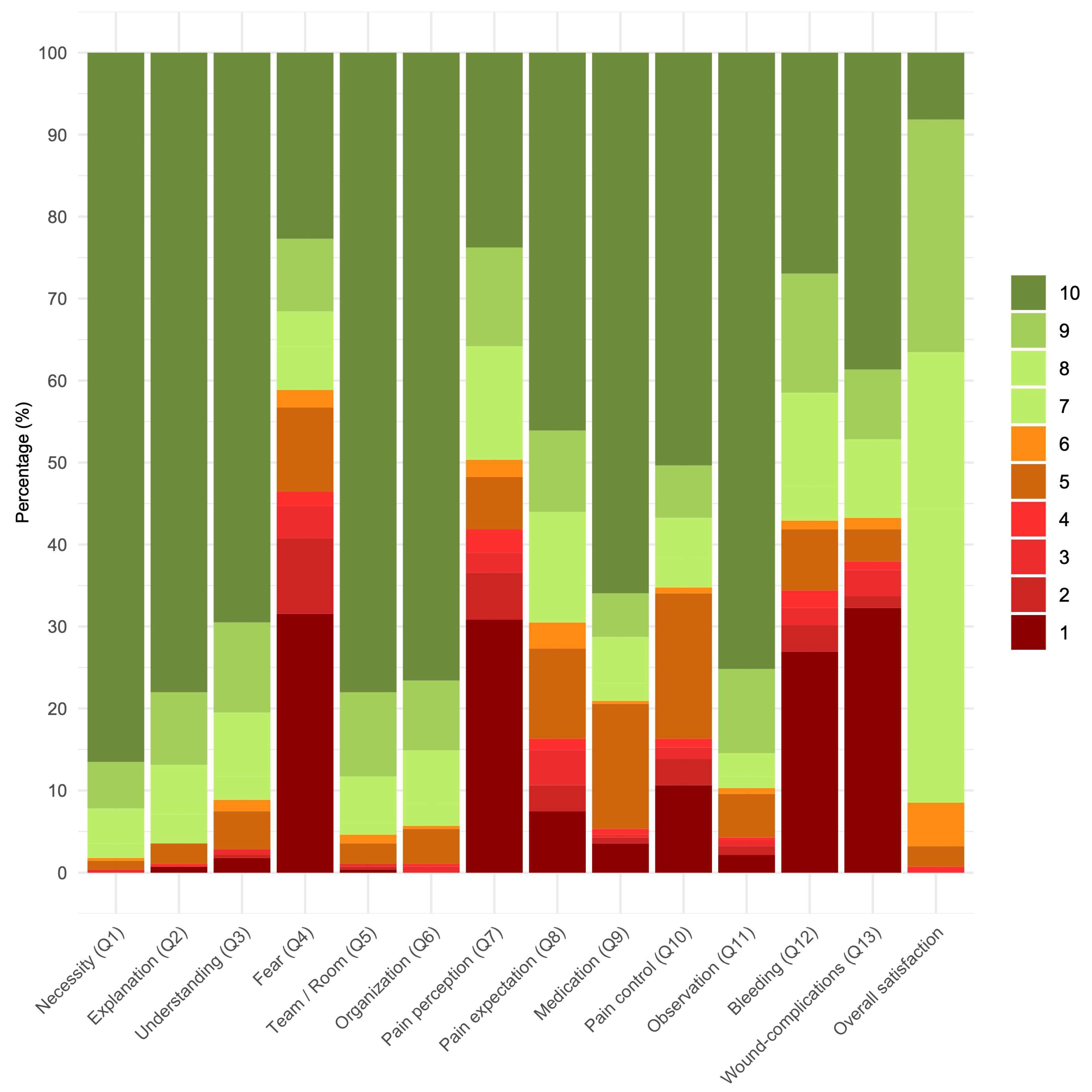

3.2. Overall Analyses of IPA PROMs and PREMs

3.3. Results According to IPA Categories

3.3.1. Procedure Perception

3.3.2. Overall Experience and Comfort

3.3.3. Pain and Medication Analysis

3.3.4. Post-Procedural Outcomes

3.4. Correlations Between PROMs

3.4.1. Correlation Between Physician Explanation and Various PROMs

3.4.2. Correlations Between Fear of the Biopsy and Pain

3.4.3. Correlations Between Expected Pain, Experienced Pain, and Pain Control

3.5. Comparison of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Between IPU-A and IPU-B

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Traina, F.; Errani, C.; Toscano, A.; Pungetti, C.; Fabbri, D.; Mazzotti, A.; Donati, D.; Faldini, C. Current concepts in the biopsy of musculoskeletal tumors: AAOS exhibit selection. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2015, 97, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didolkar, M.M.; Anderson, M.E.; Hochman, M.G.; Rissmiller, J.G.; Goldsmith, J.D.; Gebhardt, M.G.; Wu, J.S. Image guided core needle biopsy of musculoskeletal lesions: Are nondiagnostic results clinically useful? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res.® 2013, 471, 3601–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, D.; Zhao, M.; Hu, T.; Zhang, G. Diagnostic yield of percutaneous core needle biopsy in suspected soft tissue lesions of extremities. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 47, 2598–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosku, N.; Heesen, P.; Studer, G.; Bode, B.; Spataro, V.; Klass, N.D.; Kern, L.; Scaglioni, M.F.; Fuchs, B. Biopsy Ratio of Suspected to Confirmed Sarcoma Diagnosis. Cancers 2022, 14, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, T. Patient-Reported Outcomes and Experience: Measuring What We Want from PROMs and PREMs; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mosku, N.; Heesen, P.; Christen, S.; Scaglioni, M.F.; Bode, B.; Studer, G.; Fuchs, B. The Sarcoma-Specific Instrument to Longitudinally Assess Health-Related Outcomes of the Routine Care Cycle. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E.C.; Eftimovska, E.; Lind, C.; Hager, A.; Wasson, J.H.; Lindblad, S. Patient reported outcome measures in practice. BMJ 2015, 350, g7818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, L.; Foley, C.M.; Hagi-Diakou, P.; Lesty, P.J.; Sandstrom, M.L.; Ramsey, I.; Kumar, S. Patients’ experiences and perspectives of patient-reported outcome measures in clinical care: A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, J.; Doll, H.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Jenkinson, C.; Carr, A.J. The routine use of patient reported outcome measures in healthcare settings. BMJ 2010, 340, c186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimone, S.; Morozov, A.P.; Wilhelm, A.; Robrahn, I.; Whitcomb, T.D.; Lin, K.Y.; Maxwell, R.W. Understanding Patient Anxiety and Pain During Initial Image-guided Breast Biopsy. J. Breast Imaging 2020, 2, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soo, M.S.; Shelby, R.A.; Johnson, K.S. Optimizing the Patient Experience during Breast Biopsy. J. Breast Imaging 2019, 1, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Dai, Y.; Wang, L.; Pan, S.; Wang, W.; Yu, H. ‘Is it painful’? A qualitative study on experiences of patients before prostate needle biopsy. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, G.L.; Finnerup, N.B.; Colloca, L.; Amanzio, M.; Price, D.D.; Jensen, T.S.; Vase, L. The magnitude of nocebo effects in pain: A meta-analysis. Pain 2014, 155, 1426–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colloca, L. Nocebo effects can make you feel pain. Science 2017, 358, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, C.C.; Singh, I.; Thaper, R.; David, A.; Singh, S.; Mathew, A.; John, M.J. Procedural Pain and Serious Adverse Events with Bone Marrow Aspiration and Biopsy: Real World Experience from India. Blood 2020, 136, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjortholm, N.; Jaddini, E.; Hałaburda, K.; Snarski, E. Strategies of pain reduction during the bone marrow biopsy. Ann. Hematol. 2013, 92, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goudreau, S.; Grimm, L.J.; Srinivasan, A.; Net, J.; Yang, R.; Dialani, V.; Dodelzon, K. Bleeding Complications After Breast Core-needle Biopsy—An Approach to Managing Patients on Antithrombotic Therapy. J. Breast Imaging 2022, 4, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, S.G.; Matthias, M.S. Patient-Clinician Communication About Pain: A Conceptual Model and Narrative Review. Pain. Med. 2018, 19, 2154–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkiya, S.H. Quality communication can improve patient-centred health outcomes among older patients: A rapid review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanalis-Miller, T.; Nudelman, G.; Ben-Eliyahu, S.; Jacoby, R. The Effect of Pre-operative Psychological Interventions on Psychological, Physiological, and Immunological Indices in Oncology Patients: A Scoping Review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 839065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinatra, R. Causes and Consequences of Inadequate Management of Acute Pain. Pain. Med. 2010, 11, 1859–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.M.H.; Hartley, R.L.; Leung, A.A.; Ronksley, P.E.; Jette, N.; Casha, S.; Riva-Cambrin, J. Preoperative predictors of poor acute postoperative pain control: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soo, M.S.; Jarosz, J.A.; Wren, A.A.; Soo, A.E.; Mowery, Y.M.; Johnson, K.S.; Yoon, S.C.; Kim, C.; Hwang, E.S.; Keefe, F.J.; et al. Imaging-Guided Core-Needle Breast Biopsy: Impact of Meditation and Music Interventions on Patient Anxiety, Pain, and Fatigue. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2016, 13, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, M.; Chang, C. Local anesthetic infusion pump for pain management following total knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2017, 18, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Obergfell, T.T.A.F.; Nydegger, K.N.; Heesen, P.; Schelling, G.; Bode-Lesniewska, B.; Studer, G.; Fuchs, B. Improving Sarcoma Outcomes: Target Trial Emulation to Compare the Impact of Unplanned and Planned Resections on the Outcome. Cancers 2024, 16, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TEQ Group. EuroQol—A new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990, 16, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boparai, J.K.; Singh, S.; Kathuria, P. How to design and validate a questionnaire: A guide. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 13, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, N. Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ 2013, 346, f167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, E. Patient-reported outcomes-harnessing patients’ voices to improve clinical care. New Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyce, M.B.; Browne, J.P.; Greenhalgh, J. The experiences of professionals with using information from patient-reported outcome measures to improve the quality of healthcare: A systematic review of qualitative research. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2014, 23, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-X.; Chen, M.-L.; Xie, L.; Zhu, H.-B.; Liu, Y.-L.; Sun, R.-J.; Zhao, B.; Deng, X.-B.; Li, X.-T.; Sun, Y.-S. Procedure-related pain during CT-guided percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsies of lung lesions: A prospective study. Cancer Imaging 2023, 23, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollazzo, F.; Tendas, A.; Conte, E.; Bianchi, M.P.; Niscola, P.; Cupelli, L.; Mauroni, M.R.; Molinari, V.; D’Apolito, A.; Pilozzi, V.; et al. Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy-related pain management. Ann. Hematol. 2014, 93, 1061–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H. The Effects of Music on Pain: A Meta-Analysis. J. Music. Ther. 2016, 53, 430–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malloy, K.M.; Milling, L.S. The effectiveness of virtual reality distraction for pain reduction: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sternbach, R.A. Pain: A Psychophysiological Analysis; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Melzack, R.; Wall, P.D. The Challenge of Pain; Penguin: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Grachev, I.D.; Fredickson, B.E.; Apkarian, A.V. Dissociating anxiety from pain: Mapping the neuronal marker N-acetyl aspartate to perception distinguishes closely interrelated characteristics of chronic pain. Mol. Psychiatry 2001, 6, 256–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kain, Z.N.; Sevarino, F.; Alexander, G.M.; Pincus, S.; Mayes, L.C. Preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain in women undergoing hysterectomy. A repeated-measures design. J. Psychosom. Res. 2000, 49, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Hout, J.H.; Vlaeyen, J.W.; Houben, R.M.; Soeters, A.P.; Peters, M.L. The effects of failure feedback and pain-related fear on pain report, pain tolerance, and pain avoidance in chronic low back pain patients. Pain 2001, 92, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althubaiti, A. Information bias in health research: Definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2016, 9, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.; Bruner, G. Social Desirability Bias: A Neglected Aspect of Validity Testing. Psychol. Mark. 2000, 17, 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Values | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55.6 ± 17.6 * | |

| Male/Female (n (%)) | 147 (52)/135 (48) | |

| Integrated Practice Units (IPUs) (n (%)) 1 | ||

| IPU-A | 146 (52) | |

| IPU-B | 136 (48) | |

| Anatomic region (n (%)) 2 | ||

| Trunk | 85 (30) | |

| Head/Neck | 7 (2) | |

| Visceral retroperitoneal | 7 (2) | |

| Visceral intraperitoneal | 3 (1) | |

| Upper extremity | 39 (14) | |

| Lower extremity | 141 (50) | |

| Origin of lesion (n (%)) | ||

| DST 3 | 192 (68) | |

| SST 4 | 48 (17) | |

| Bone | 43 (15) | |

| Benign/malignant (n (%)) 5 | 181 (64)/101 (36) | |

| PREMs | PROMs | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure Perception | Overall Experience and Comfort | Pain and Medication Analysis | Post-Procedural Outcomes |

| Necessity (Q1) Explanation (Q2) Understanding (Q3) Fear (Q4) | Team/Room (Q5) Organization (Q6) | Pain perception (Q7) Pain expectation (Q8) Medication (Q9) Pain Control (Q10) | Observation (Q11) Bleeding (Q12) Wound complications (Q13) |

| PROM Domain | Median (IQR) | 0 (n(%)) | 1 (n(%)) | 2 (n(%)) | 3 (n(%)) | 4 (n(%)) | 5 (n(%)) | 6 (n(%)) | 7 (n(%)) | 8 (n(%)) | 9 (n(%)) | 10 (n(%)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 necessity | 10 (10–10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.4) | 5 (1.8) | 12 (4.3) | 16 (5.7) | 244 (86.5) |

| Q2 explanation | 10 (10–10) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 7 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 10 (3.5) | 17 (6.0) | 25 (8.9) | 220 (78.0) |

| Q3 understanding | 10 (9–10) | 0 (0) | 5 (1.8) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 13 (4.6) | 4 (1.4) | 8 (2.8) | 22 (7.8) | 31 (11.0) | 196 (69.5) |

| Q4 fear | 5 (1–9) | 0 (0) | 89 (31.6) | 26 (9.2) | 11 (3.9) | 5 (1.8) | 29 (10.3) | 6 (2.1) | 15 (5.3) | 12 (4.3) | 25 (8.9) | 64 (22.7) |

| Q5 team/room | 10 (10–10) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 7 (2.5) | 3 (1.1) | 4 (1.4) | 16 (5.7) | 29 (10.3) | 220 (78.0) |

| Q6 organization | 10 (10–10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | 12 (4.3) | 1 (0.4) | 8 (2.8) | 18 (6.4) | 24 (8.5) | 216 (76.6) |

| Q7 pain perception | 6 (1–9) | 0 (0) | 87 (30.8) | 16 (5.7) | 7 (2.5) | 8 (2.8) | 18 (6.4) | 6 (2.1) | 12 (4.3) | 27 (9.6) | 34 (12.1) | 67 (23.8) |

| Q8 pain expectation | 9 (5–10) | 0 (0) | 21 (7.4) | 9 (3.2) | 12 (4.3) | 4 (1.4) | 31 (11.0) | 9 (3.2) | 14 (5.0) | 24 (8.5) | 28 (9.9) | 130 (46.1) |

| Q9 medication | 10 (8–10) | 0 (0) | 10 (3.5) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | 43 (15.2) | 1 (0.4) | 6 (2.1) | 16 (5.7) | 15 (5.3) | 186 (66.0) |

| Q10 pain control | 10 (5–10) | 0 (0) | 30 (10.6) | 9 (3.2) | 4 (1.4) | 3 (1.1) | 50 (17.7) | 2 (0.7) | 10 (3.5) | 14 (5.0) | 18 (6.4) | 142 (50.4) |

| Q11 observation | 10 (10–10) | 0 (0) | 6 (2.1) | 3 (1.1) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | 15 (5.3) | 2 (0.7) | 4 (1.4) | 8 (2.8) | 29 (10.3) | 212 (75.2) |

| Q12 Bleeding | 8 (1–10) | 0 (0) | 76 (27.0) | 9 (3.2) | 6 (2.1) | 6 (2.1) | 21 (7.4) | 3 (1.1) | 12 (4.3) | 32 (11.3) | 41 (14.5) | 76 (27.0) |

| Q13 wound complications | 8 (1–10) | 0 (0) | 91 (32.3) | 4 (1.4) | 9 (3.2) | 3 (1.1) | 11 (3.9) | 4 (1.4) | 4 (1.4) | 23 (8.2) | 24 (8.5) | 109 (38.7) |

| Q14 overall satisfaction | 8 (7–9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.7) | 7 (2.5) | 16 (5.3) | 100 (35.5) | 54 (19.1) | 80 (28.4) | 23 (8.2) |

| IPA Domain | IPU-A | IPU-B | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q4 fear | 4.5 ± 3.7 * 3 (1–8.8) ** | 5.8 ± 3.7 6 (2–10) | 0.002 |

| Q7 pain perception | 4.8 ± 3.7 4 (1–9) | 6.4 ± 3.7 8 (1–10) | <0.001 |

| Q5 team/room | 9.4 ± 1.3 10 (9–10) | 9.6 ± 1.3 10 (10–10) | 0.047 |

| Q9 overall satisfaction | 7.7 ± 1.2 7 (7–9) | 8.1 ± 1.3 8 (7–9) | 0.003 |

| * mean ± SD, all such values ** median (IQR), all such values |

| Positive Correlations | Negative Correlations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PREMs/PROMs | rho-/p-Value | PREMs/PROMs | rho-/p-Value |

| explanation and understanding | 0.619/<0.0001 | explanation and fear | −0.117/0.052 |

| explanation and necessity | 0.288/<0.0001 | fear and pain control | −0.287/<0.0001 |

| fear and pain | 0.653/<0.0001 | pain perception and control | −0.257/<0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jaeger, R.; Mosku, N.; Paganini, D.; Schelling, G.; van Oudenaarde, K.; Falkowski, A.L.; Guggenberger, R.; Studer, G.; Bode-Lesniewska, B.; Heesen, P.; et al. Enhancing Patient Experience in Sarcoma Core Biopsies: The Role of Communication, Anxiety Management, and Pain Control. Cancers 2024, 16, 3901. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16233901

Jaeger R, Mosku N, Paganini D, Schelling G, van Oudenaarde K, Falkowski AL, Guggenberger R, Studer G, Bode-Lesniewska B, Heesen P, et al. Enhancing Patient Experience in Sarcoma Core Biopsies: The Role of Communication, Anxiety Management, and Pain Control. Cancers. 2024; 16(23):3901. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16233901

Chicago/Turabian StyleJaeger, Ruben, Nasian Mosku, Daniela Paganini, Georg Schelling, Kim van Oudenaarde, Anna L. Falkowski, Roman Guggenberger, Gabriela Studer, Beata Bode-Lesniewska, Philip Heesen, and et al. 2024. "Enhancing Patient Experience in Sarcoma Core Biopsies: The Role of Communication, Anxiety Management, and Pain Control" Cancers 16, no. 23: 3901. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16233901

APA StyleJaeger, R., Mosku, N., Paganini, D., Schelling, G., van Oudenaarde, K., Falkowski, A. L., Guggenberger, R., Studer, G., Bode-Lesniewska, B., Heesen, P., & Fuchs, B., on behalf of the SwissSarcomaNetwork. (2024). Enhancing Patient Experience in Sarcoma Core Biopsies: The Role of Communication, Anxiety Management, and Pain Control. Cancers, 16(23), 3901. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16233901