Impacts of Employment Status, Partnership, Cancer Type, and Surgical Treatment on Health-Related Quality of Life in Irradiated Head and Neck Cancer Survivors

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Variables and Measures

2.3. Statistical Analyses

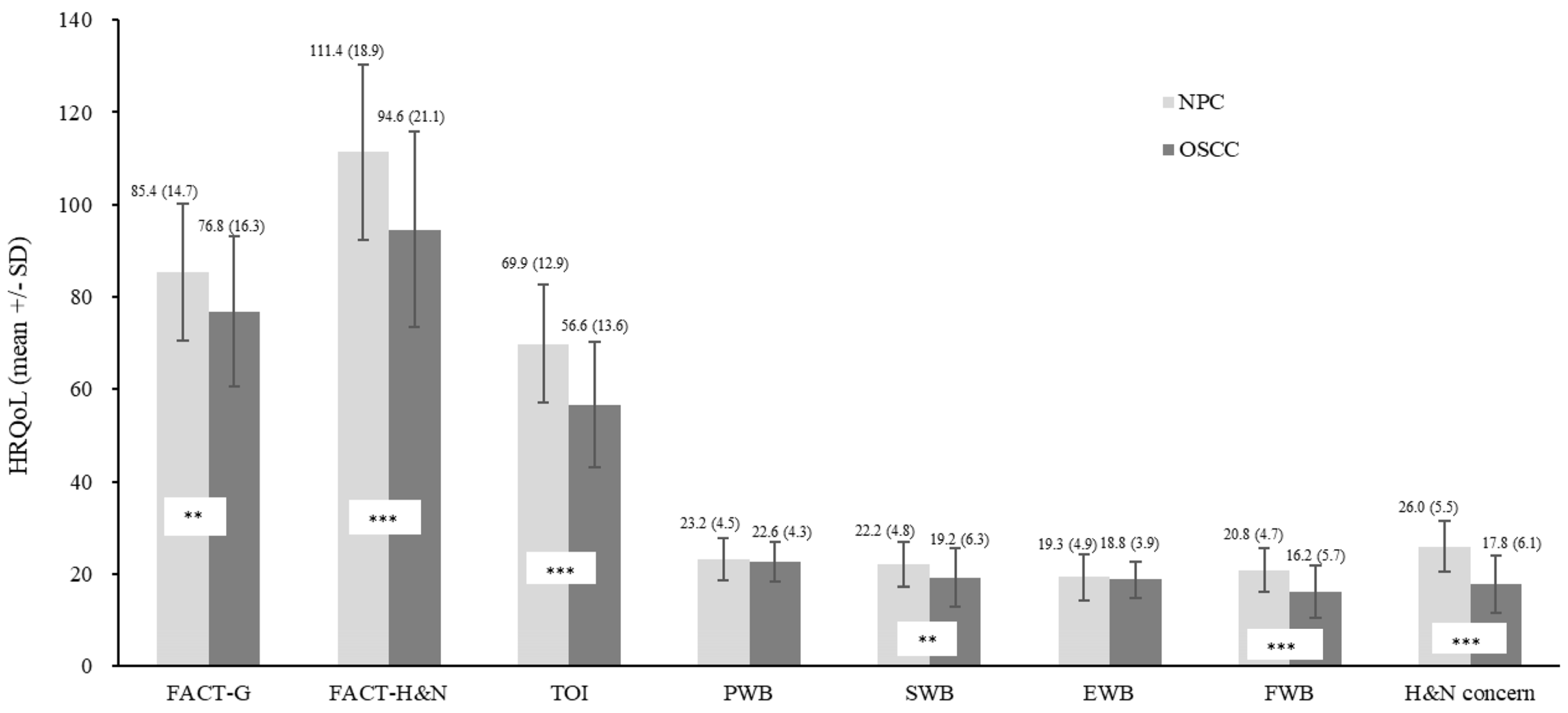

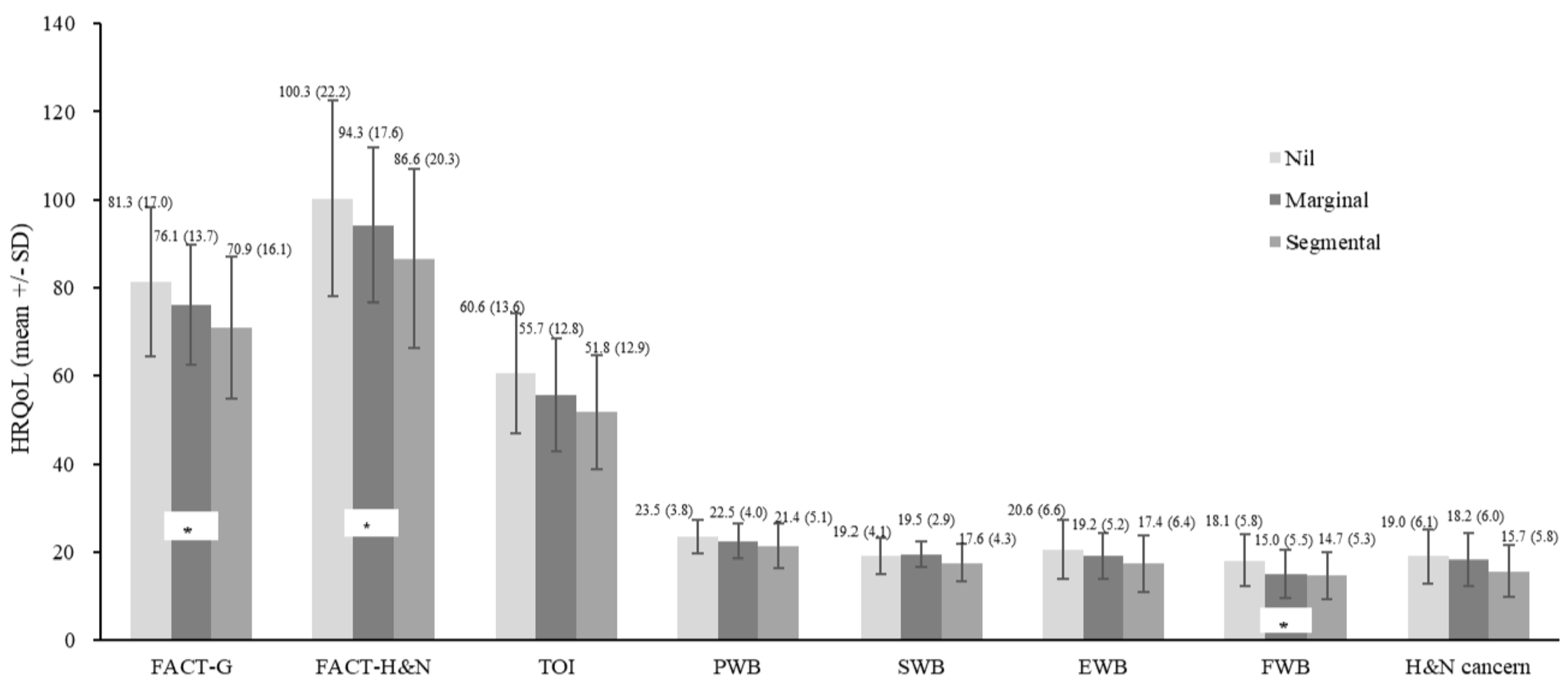

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Partnership in HRQoL

4.2. Surgery for Oral Cavity Cancer Patients

4.3. Employment Impact to HRQoL

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gomes, E.P.A.A.; Aranha, A.M.F.; Borges, A.H.; Volpato, L.E.R. Head and neck cancer patients’ quality of life: Analysis of three instruments. J. Dent. Shiraz Univ. Med. Sci. 2020, 21, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma; Mishra, G.; Parikh, V. Quality of Life in Head and Neck Cancer Patients. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2019, 71, 927–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, L.-J.; Hsu, L.-J.; Lo, W.-L.; Cheng, W.-C.; Shueng, P.-W.; Hsieh, C.-H. Health-related quality of life and utility in head and neck cancer survivors. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Smith, J.; Marwah, R.; Edkins, O. Return to work in patients with head and neck cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Head. Neck 2022, 44, 2904–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkilä, R.; Carpén, T.; Hansen, J.; Heikkinen, S.; Lynge, E.; Martinsen, J.I.; Selander, J.; Mehlum, I.S.; Torfadóttir, J.E.; Mäkitie, A.; et al. Socio-economic status and head and neck cancer incidence in the Nordic countries. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2024, 53, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorn, L.; Lommen, J.; Sproll, C.; Krüskemper, G.; Handschel, J.; Nitschke, J.; Prokein, B.; Gellrich, N.C.; Holtmann, H. Evaluation of patient specific care needs during treatment for head and neck cancer. Oral. Oncol. 2020, 110, 104898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh, Y.; Seagroatt, V.; Goldacre, M.; McCulloch, P. Impact of socio-economic deprivation on death rates after surgery for upper gastrointestinal tract cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2006, 95, 940–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligier, K.; Dejardin, O.; Launay, L.; Benoit, E.; Babin, E.; Bara, S.; Lapôtre-Ledoux, B.; Launoy, G.; Guizard, A.V. Health professionals and the early detection of head and neck cancers: A population-based study in a high incidence area. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.T.; Johnson-Obaseki, S.; Hwang, E.; Connell, C.; Corsten, M. The relationship between survival and socio-economic status for head and neck cancer in Canada. J. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2014, 43, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M.R.; Irish, J.C.; Devins, G.M.; Rodin, G.M.; Gullane, P.J. Psychosocial adjustment in head and neck cancer: The impact of disfigurement, gender and social support. Head. Neck 2003, 25, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rast, J.; Zebralla, V.; Dietz, A.; Wichmann, G.; Wiegand, S. Cancer-associated financial burden in German head and neck cancer patients. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1329242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- List, M.A.; Knackstedt, M.; Liu, L.; Kasabali, A.; Mansour, J.; Pang, J.; Asarkar, A.A.; Nathan, C.-A. Enhanced recovery after surgery, current, and future considerations in head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2023, 8, 1240–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, I.M.; Arenilla, M.J.; Alarcón, D.; Jaenes, J.C.; Trujillo, M. Psychological impact after treatment in patients with head and neck cancer. Med. Oral. Patol. Oral. Cir. Bucal 2023, 28, e467–e473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.T.-C.; Chang, C.-H.; Juang, Y.-Y.; Hsiao, J.-C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Huang, S.-F.; Huang, Y.-C.; Kuan, K.H.-Y.; Liao, C.-T.; Wang, H.M.; et al. Internal consistency of the traditional Chinese character version of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Head and Neck (FACT-H&N). Chang. Gung Med. J. 2008, 31, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pais-Ribeiro, J.L. Quality of life is a primary end-point in clinical settings. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 23, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdez, J.A.; Brennan, M.T. Impact of Oral Cancer on Quality of Life. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 62, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.-R.; Ying, H.-M.; Kong, F.-F.; Zhai, R.-P.; Hu, C.-S. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy was associated with a higher severe late toxicity rate in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients compared with radiotherapy alone: A meta-analysis based on randomized controlled trials. Radiat. Oncol. 2015, 10, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, L.; Corry, J.; Ringash, J.; Rischin, D. Quality of Life, Toxicity and Unmet Needs in Nasopharyngeal Cancer Survivors. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, M.; Arnovitz, E.; Frenkiel, S.; Hier, M.; Zeitouni, A.; Kost, K.; Mlynarek, A.; Black, M.; MacDonald, C.; Richardson, K.; et al. Psychosocial outcomes of human papillomavirus (HPV)- and non-HPV-related head and neck cancers: A longitudinal study. Psychooncology 2022, 31, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.R.; Yack, M.; Kikuchi, K.; Stevens, L.; Merchant, L.; Buys, C.; Gottschalk, L.; Frame, M.; Mussetter, J.; Younkin, S.; et al. Research-practice partnership: Supporting rural cancer survivors in Montana. Cancer Causes Control 2023, 34, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.L.; Nolan, T.S.; Chiu, Y.-W.; Ricks, L.; Camata, S.G.; Craft, B.; Meneses, K. A Partnership in Health-Related Social Media for Young Breast Cancer Survivors. Health Promot. Pract. 2020, 21, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, E.E.; LaMonte, S.J.; Erb, N.L.; Beckman, K.L.; Sadeghi, N.; Hutcheson, K.A.; Stubblefield, M.D.; Abbott, D.M.; Fisher, P.S.; Stein, K.D.; et al. American Cancer Society Head and Neck Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016, 66, 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, T.-M.; Lin, C.-R.; Chi, Y.-C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Chen, E.Y.-C.; Kang, C.-J.; Huang, S.-F.; Juang, Y.-Y.; Huang, C.-Y.; Chang, J.T.-C. Body image in head and neck cancer patients treated with radiotherapy: The impact of surgical procedures. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warshavsky, A.; Fliss, D.M.; Frenkel, G.; Kupershmidt, A.; Moav, N.; Rosen, R.; Sechter, M.; Shapira, U.; Abu-Ghanem, S.; Yehuda, M.; et al. Long-term health-related quality of life after mandibular resection and reconstruction. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 276, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Yoon, H. Health-Related Quality of Life among Cancer Survivors Depending on the Occupational Status. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.G.; Wu, L.M.; Austin, J.E.; Valdimarsdottir, H.; Basmajian, K.; Vu, A.; Rowley, S.D.; Isola, L.; Redd, W.H.; Rini, C. Economic survivorship stress is associated with poor health-related quality of life among distressed survivors of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Psychooncology 2013, 22, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekenga, C.C.; Kim, B.; Kwon, E.; Park, S. Multimorbidity and Employment Outcomes among Middle-Aged US Cancer Survivors. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2022, 64, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.-H.; Yun, Y.H.; Park, S.; Kim, Y.A.; Park, S.-Y.; Bae, D.-S.; Nam, J.H.; Park, C.T.; Cho, C.-H.; Lee, J.-M. The correlates of unemployment and its association with quality of life in cervical cancer survivors. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2013, 24, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawachi, I.; Berkman, L.F. Social ties and mental health. J. Urban Health 2001, 78, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N (%) | Cancer Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 150) | NPC (n = 60) | OSCC (n = 90) | ||

| Sociodemographic | ||||

| Age (years) | ≤50 | 69 (46.0) | 31 (51.7) | 38 (42.2) |

| >50 | 81 (54.0) | 29 (48.3) | 52 (57.8) | |

| Gender | Male | 128 (85.3) | 45 (75.0) | 83 (92.2) |

| Female | 22 (14.7) | 15 (25.0) | 7 (7.8) | |

| Partnership | No | 32 (21.3) | 15 (25.0) | 17 (18.9) |

| Yes | 118 (78.7) | 45 (75.0) | 73 (81.1) | |

| Employment status | No job | 38 (25.3) | 5 (13.8) | 33 (36.7) |

| Part-time job | 55 (36.7) | 24 (40.0) | 31 (34.4) | |

| Full-time job | 57 (38.0) | 31 (51.7) | 26 (28.9) | |

| Education | Primary | 27 (18.0) | 8 (13.3) | 19 (21.1) |

| Junior high | 43 (28.7) | 17 (28.3) | 26 (28.9) | |

| Senior high | 48 (32.0) | 16 (26.7) | 32 (35.6) | |

| University & above | 32 (21.3) | 19 (31.7) | 13 (14.4) | |

| Clinical condition | ||||

| Time after treatment | Within two years | 66 (44.0) | 21 (35.0) | 45 (50.0) |

| More than two years | 84 (56.0) | 39 (65.0) | 45 (50.0) | |

| Treatment # | RT | 44 (29.3) | 10 (16.7) | 34 (37.8) |

| CCRT | 106 (70.7) | 50 (83.3) | 56 (62.2) | |

| Surgery | No | 60 (40.0) | 60 (100) | 0 (0.0) |

| Yes | 90 (60.0) | 0 (0.0) | 90 (100) | |

| Surgical approach for OSCC | ||||

| Glossectomy | Other surgery * | 46 (51.1) | ||

| Partial | 25 (27.8) | |||

| Total | 19 (21.1) | |||

| Facial skin | Preserved | 48 (53.3) | ||

| Sacrificed | 42 (46.7) | |||

| Mouth angle | Preserved | 64 (71.1) | ||

| Sacrificed | 26 (28.9) | |||

| Mandibulectomy | Nil | 39 (43.3) | ||

| Marginal | 24 (26.7) | |||

| Segmental | 27 (30.0) | |||

| Maxillectomy | Nil | 66 (73.3) | ||

| Inferior | 24 (26.7) | |||

| Variable | t/f/z/χ2 | FACT-G | FACT-H&N | PWB | EWB | SWB | FWB | H&N | TOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | |||||||||

| Age (years) | All (t) | 0.11 | 0.46 | −0.50 | −1.53 | 0.44 | 1.37 | 1.19 | 0.96 |

| NPC (t) | 0.57 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 0.14 | −0.04 | 1.08 | 1.15 | 1.11 | |

| OSCC (t) | −0.67 | −0.53 | −1.31 | −2.48 * | 0.22 | 0.49 | −0.03 | −0.22 | |

| Gender | All (t) | 0.47 | 1.06 | −0.05 | −1.29 | 1.48 | 1.23 | 2.23 * | 1.53 |

| NPC (z) | −0.49 | −038 | −0.79 | −0.97 | −0.50 | −0.66 | −0.68 | 0.00 | |

| OSCC (z) | −0.80 | −0.66 | −0.31 | −0.14 | −1.32 | −1.05 | −0.75 | −0.65 | |

| Partnership | All (t) | −1.44 | −1.23 | −1.24 | 0.83 | −2.51 * | −0.78 | −0.48 | −0.91 |

| NPC (z) | −0.09 | 0.00 | −0.79 | −1.16 | −1.10 | −0.58 | −0.10 | −0.12 | |

| OSCC (z) | −2.06 * | −1.94 | −1.28 | −0.78 | −2.61 ** | −1.38 | −1.64 | −1.76 | |

| Employment status | All (f) | 9.22 *** | 12.13 *** | 4.56 * | 0.61 | 6.71 ** | 14.16 *** | 13.58 *** | 15.54 *** |

| NPC (χ2) | 3.31 | 2.24 | 5.24 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 3.55 | 0.11 | 2.32 | |

| OSCC (f) | 4.24 * | 5.75 ** | 2.12 | 0.11 | 4.21 * | 5.98 ** | 7.66 ** | 7.64 ** | |

| Education | All (f) | 1.99 | 3.15 * | 1.19 | 1.66 | 0.74 | 2.49 | 5.18 ** | 4.05 ** |

| NPC (χ2) | 1.60 | 3.09 | 4.51 | 3.38 | 0.96 | 1.42 | 5.47 | 4.99 | |

| OSCC (χ2) | 1.69 | 2.06 | 0.51 | 1.24 | 1.13 | 1.89 | 4.37 | 2.19 | |

| Clinical condition | |||||||||

| Cancer type | All (t) | 3.29 ** | 4.97 *** | 0.79 | 0.73 | 3.27 ** | 5.10 *** | 8.34 *** | 5.99 *** |

| Time after | All (t) | −1.28 | −1.81 | −1.05 | −0.46 | −1.26 | −1.15 | −2.67 ** | −2.04 * |

| Irradiation | NPC (z) | −0.69 | −0.79 | −0.89 | −0.48 | −0.56 | −0.36 | −1.26 | −1.12 |

| OSCC (t) | −1.02 | −1.25 | −0.66 | −1.18 | −1.01 | −0.49 | −1.59 | −1.13 | |

| Treatment: | All (t) | −2.91 ** | −2.76 ** | −1.92 | −2.51 * | −2.09 * | −2.44 * | −1.81 | −2.48 * |

| RT vs CCRT | NPC (z) | −0.76 | −0.63 | −0.81 | −0.44 | −0.42 | −1.13 | −0.24 | −0.77 |

| OSCC (t) | −1.95 | −1.49 | −1.84 | −2.47 * | −1.46 | −0.87 | 0.02 | −0.94 | |

| Surgery # | All (t) | 3.29 ** | 4.97 *** | 0.79 | 0.73 | 3.27 ** | 5.10 *** | 8.34 *** | 5.99 *** |

| Surgical approach for OSCC | |||||||||

| Glossectomy (χ2) | 2.11 | 1.11 | 0.89 | 0.60 | 4.00 | 2.01 | 0.05 | 0.64 | |

| Facial skin (t) | 1.88 | 1.69 | 0.47 | 0.79 | 2.26 * | 2.02 * | 0.80 | 1.36 | |

| Mouth angle (z) | −1.18 | −1.10 | −0.03 | −0.38 | −1.98 * | −1.82 | −0.55 | −0.79 | |

| Mandibulectomy (f) | 3.4 5* | 3.56 * | 2.02 | 1.84 | 2.28 | 3.80 * | 2.44 | 3.65 * | |

| Maxillectomy (t) | 0.97 | 1.19 | 0.34 | −0.62 | 0.87 | 2.01 * | 1.52 | 1.64 | |

| Multiple Linear Regression Model a for All Patients (n = 150) | ||||

| Reduced model | ||||

| 95% CI | ||||

| Estimate | p | Lower | Upper | |

| Intercept | 97.09 | <0.001 | 88.37 | 105.80 |

| Cancer type: | ||||

| OSCC (ref: NPC) | −11.55 | 0.001 | −18.39 | −4.71 |

| Employment status: | ||||

| Part-time job (ref: no job) | 11.13 | 0.009 | 2.80 | 19.46 |

| Full-time job (ref: no job) | 14.41 | 0.001 | 5.87 | 22.95 |

| Multiple linear regression model b for patients with OSCC (n = 90) | ||||

| Reduced model | ||||

| 95% CI | ||||

| Estimate | p | Lower | Upper | |

| Intercept | 80.84 | <0.001 | 70.59 | 91.09 |

| Partnership: | ||||

| Partnership (ref: no partner) | 13.14 | 0.017 | 2.41 | 23.86 |

| Employment status: | ||||

| Full-time job (ref: no job) | 12.70 | 0.018 | 2.23 | 23.18 |

| Surgical treatment: | ||||

| Segmental (ref: no mandibulectomy) | −11.31 | 0.017 | −20.55 | −2.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, C.-R.; Hung, T.-M.; Shen, E.Y.-L.; Cheng, A.-J.; Chang, P.-H.; Huang, S.-F.; Kang, C.-J.; Fang, T.-J.; Lee, L.-A.; Chang, C.-H.; et al. Impacts of Employment Status, Partnership, Cancer Type, and Surgical Treatment on Health-Related Quality of Life in Irradiated Head and Neck Cancer Survivors. Cancers 2024, 16, 3366. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16193366

Lin C-R, Hung T-M, Shen EY-L, Cheng A-J, Chang P-H, Huang S-F, Kang C-J, Fang T-J, Lee L-A, Chang C-H, et al. Impacts of Employment Status, Partnership, Cancer Type, and Surgical Treatment on Health-Related Quality of Life in Irradiated Head and Neck Cancer Survivors. Cancers. 2024; 16(19):3366. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16193366

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Ching-Rong, Tsung-Min Hung, Eric Yi-Liang Shen, Ann-Joy Cheng, Po-Hung Chang, Shiang-Fu Huang, Chung-Jan Kang, Tuan-Jen Fang, Li-Ang Lee, Chih-Hung Chang, and et al. 2024. "Impacts of Employment Status, Partnership, Cancer Type, and Surgical Treatment on Health-Related Quality of Life in Irradiated Head and Neck Cancer Survivors" Cancers 16, no. 19: 3366. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16193366

APA StyleLin, C.-R., Hung, T.-M., Shen, E. Y.-L., Cheng, A.-J., Chang, P.-H., Huang, S.-F., Kang, C.-J., Fang, T.-J., Lee, L.-A., Chang, C.-H., & Chang, J. T.-C. (2024). Impacts of Employment Status, Partnership, Cancer Type, and Surgical Treatment on Health-Related Quality of Life in Irradiated Head and Neck Cancer Survivors. Cancers, 16(19), 3366. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16193366