Clinicopathologic Features of Early Gastric Cancer after Helicobacter pylori Eradication in Japanese Patients: Comparative Study between Early (<10 Years) and Late (>10 Years) Onset

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

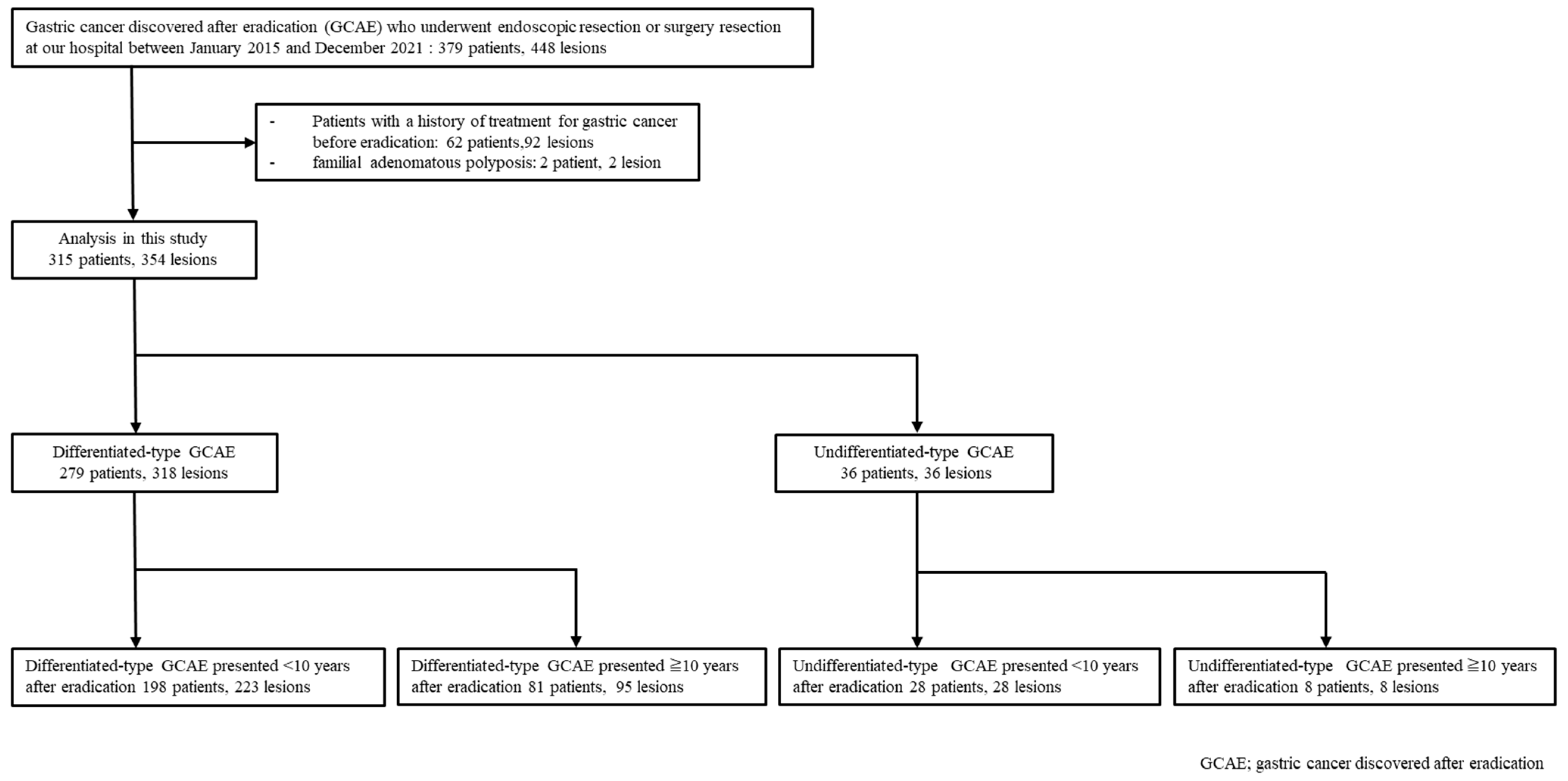

2.2. Patients

2.3. Data Collection and Definitions

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of the Patients and Lesions

3.2. Comparison of D-GCAE Presented within and >10 Years after Eradication

3.3. Comparison of UD-GCAE Presented within and over 10 Years after Eradication

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Parsonnet, J.; Friedman, G.D.; Vandersteen, D.P.; Chang, Y.; Vogelman, J.H.; Orentreich, N.; Sibley, R.K. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 325, 1127–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, A.; Stemmermann, G.N.; Chyou, P.H.; Kato, I.; Perez-Perez, G.I.; Blaser, M.J. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma among Japanese Americans in Hawaii. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 325, 1132–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamagata, H.; Kiyohara, Y.; Aoyagi, K.; Kato, I.; Iwamoto, H.; Nakayama, K.; Shimizu, H.; Tanizaki, Y.; Arima, H.; Shonihara, N.; et al. Impact of Helicobacter pylori infection on gastric cancer incidence in a general Japanese population: The Hisayama study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000, 160, 1962–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, N.; Okamoto, S.; Yamamoto, S.; Matsumura, N.; Yamaguchi, S.; Yamakido, M.; Taniyama, K.; Sasaki, N.; Schlemper, R.J. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooi, J.K.Y.; Lai, W.Y.; Ng, W.K.; Suen, M.M.Y.; Underwood, F.E.; Tanyingoh, D.; Malfertheiner, P.; Graham, D.Y.; Wong, V.W.S.; Wu, J.C.Y.; et al. Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plummer, M.; Franceschi, S.; Muñoz, N. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. IARC Sci. Publ. 2004, 157, 311–326. [Google Scholar]

- Uemura, N.; Mukai, T.; Okamoto, S.; Yamaguchi, S.; Mashiba, H.; Taniyama, K.; Sasaki, N.; Haruma, K.; Sumii, K.; Kajiyama, G. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on subsequent development of cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1997, 6, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukase, K.; Kato, M.; Kikuchi, S.; Inoue, K.; Uemura, N.; Okamoto, S.; Terao, S.; Amagai, K.; Hayashi, S.; Asaka, M.; et al. Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: An open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008, 372, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Take, S.; Mizuno, M.; Ishiki, K.; Nagahara, K.; Yoshida, T.; Yokota, K.; Oguma, K. Baseline gastric mucosal atrophy is a risk factor associated with the development of gastric cancer after Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in patients with peptic ulcer diseases. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 42 (Suppl. S17), 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, K.; Hirata, Y.; Yanai, A.; Shibata, W.; Ohmae, T.; Mitsuno, Y.; Maeda, S.; Watabe, H.; Yamaji, Y.; Okamoto, M.; et al. The effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on reducing the incidence of gastric cancer. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2008, 42, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabe, K.; Takahashi, M.; Oizumi, H.; Tsukuma, H.; Shibata, A.; Fukase, K.; Matsuda, T.; Takeda, H.; Kawata, S. Does Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy for peptic ulcer prevent gastric cancer? World J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 4290–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.Y.; Lee, Y.C.; Graham, D.Y. The eradication of Helicobacter pylori to prevent gastric cancer: A critical appraisal. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 13, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruma, K.; Kato, M.; Inoue, K.; Murakami, K.; Kamada, T. Kyoto Classification of Gastritis; Nihon Medical Center: Tokyo, Japan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer 2011, 14, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugano, K. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the incidence of gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer 2019, 22, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruma, K.; Suzuki, T.; Tsuda, T.; Yoshihara, M.; Sumii, K.; Kajiyama, G. Evaluation of tumor growth rate in patients with early gastric carcinoma of the elevated type. Gastrointest. Radiol. 1991, 16, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, M.; Asaka, M.; Ono, S.; Nakagawa, M.; Nakagawa, S.; Shimizu, Y.; Chuma, M.; Kawakami, H.; Komatsu, Y.; Hige, S.; et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori for primary gastric cancer and secondary gastric cancer after endoscopic mucosal resection. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 42 (Suppl. S17), 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maehata, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Fujisawa, K.; Esaki, M.; Moriyama, T.; Asano, K.; Fuyuno, Y.; Yamaguchi, K.; Egashira, I.; Kim, H.; et al. Long-term effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the development of metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2012, 75, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.E.; Jung, H.Y.; Kang, J.; Park, Y.S.; Baek, S.; Jung, J.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Kim, M.; Ahn, J.Y.; Choi, K.; et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on metachronous recurrence after endoscopic resection of gastric neoplasm. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 109, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Take, S.; Mizuno, M.; Ishiki, K.; Yoshida, T.; Ohara, N.; Yokota, K.; Oguma, K.; Okada, H.; Yamamoto, K. The long-term risk of gastric cancer after the successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 46, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Take, S.; Mizuno, M.; Ishiki, K.; Hamada, F.; Yoshida, T.; Yokota, K.; Okada, H.; Yamamoto, K. Seventeen-year effects of eradicating Helicobacter pylori on the prevention of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer; a prospective cohort study. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 50, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Take, S.; Mizuno, M.; Ishiki, K.; Kusumoto, C.; Imada, T.; Hamada, F.; Yoshida, T.; Yokota, K.; Mitsuhashi, T.; Okada, H. Risk of gastric cancer in the second decade of follow-up after Helicobacter pylori eradication. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 55, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodama, M.; Murakami, K.; Okimoto, T.; Sato, R.; Masahiro, U.; Abe, T.; Shiota, S.; Nakagawa, Y.; Mizukami, K.; Fujioka, T. Ten-year prospective follow-up of histological changes at 5 points on the gastric mucosa as recommended by the updated Sydney system after Helicobacter pylori eradication. J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 47, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, M.; Okimoto, T.; Mizukami, K.; Hirashita, Y.; Wada, Y.; Fukuda, M.; Matsunari, O.; Kazuhisa, O.; Ogawa, R.; Fukuda, K.; et al. Gastric mucosal changes, and sex differences therein, after Helicobacter pylori eradication: A long-term prospective follow-up study. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 36, 2210–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, B.C.; Lam, S.K.; Wong, W.M.; Chen, J.S.; Zheng, T.T.; Feng, R.E.; Lai, K.C.; Hu, W.H.; Yuen, S.T.; Leung, S.Y.; et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004, 291, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, J.W.; Hahm, K.B. Rejuvenation of atrophic gastritis in the elderly. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 25, 434–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adachi, Y.; Yasuda, K.; Inomata, M.; Sato, K.; Shiraishi, N.; Kitano, S. Pathology and prognosis of gastric carcinoma: Well versus poorly differentiated type. Cancer 2000, 89, 1418–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noda, S.; Soejima, K.; Inokuchi, K. Clinicopathological analysis of the intestinal type and diffuse type of gastric carcinoma. Jpn. J. Surg. 1980, 10, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, R.; Okada, H.; Kato, J.; Makidono, C.; Hori, S.; Kawahara, Y.; Miyoshi, M.; Yumoto, E.; Imagawa, A.; Toyokawa, T.; et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication reduced the incidence of gastric cancer, especially of the intestinal type. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 25, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodama, M.; Mizukami, K.; Hirashita, Y.; Okimoto, T.; Wada, Y.; Fukuda, M.; Ozaka, S.; Kudo, Y.; Ito, K.; Ogawa, R.; et al. Differences in clinical features and morphology between differentiated and undifferentiated gastric cancer after Helicobacter pylori eradication. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Fujisaki, J.; Namikawa, K.; Hoteya, S.; Sasaki, A.; Shibagaki, K.; Yao, K.; Abe, S.; Oda, I.; Ueyama, H.; et al. Multicenter study of invasive gastric cancer detected after 10 years of Helicobacter pylori eradication in Japan: Clinical, endoscopic, and histopathologic characteristics. DEN Open 2024, 4, e345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Zheng, X.D.; Wang, J.M.; Geng, W.B.; Wang, X. Undifferentiated-predominant mixed-type early gastric cancer is more aggressive than pure undifferentiated type: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e054473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishibashi, F.; Suzuki, S.; Nagai, M.; Mochida, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Morishita, T. A Close Follow-Up Strategy in the Short Period of Time after Helicobacter pylori Eradication Contributes to Earlier Detection of Gastric Cancer. Digestion 2023, 104, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Baseline Characteristics | Differentiated-Type GCAE | Undifferentiated-Type GCAE | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 279 Patients, 318 Lesions) | (n = 36 Patients, 36 Lesions) | ||

| Mean age, y. o. [range] | 71 (40–86) | 67 (39–87) | 70 (39–87) |

| Sex, male | 211 (76) | 19 (52) | 230 (73.0) |

| Mean tumor size, mm. [range] | 10 (2–90) | 15 (3–70) | 10 (2–90) |

| Smoking | 172 (62) | 16 (44) | 188 (60) |

| Gastric cancer family history, n (%) | 82 (29) | 13 (26) | 95 (30) |

| Mean eradication period | 5 (1–27) | 4 (1–30) | 5 (1–30) |

| Gastric mucosal atrophy | |||

| Mild | 20 (8) | 5 (14) | 25 (8) |

| Moderate | 111 (38) | 20 (56) | 131 (41) |

| Severe | 148 (54) | 11 (40) | 159 (51) |

| Location | |||

| Upper third | 38 (12) | 5 (14) | 43 (12) |

| Middle third | 147 (46) | 21 (58) | 168 (47) |

| Lower third | 133 (42) | 10 (28) | 143 (41) |

| Macroscopic type | |||

| Superficial elevated | 95 (30) | 4 (11) | 99 (28) |

| Superficial depressed | 223 (70) | 32 (89) | 255 (72) |

| Treatment | |||

| Endoscopic resection | 293 (92) | 19 (53) | 312 (88) |

| Surgical resection | 25 (8) | 17 (47) | 42 (12) |

| Invasion depth | |||

| Mucosa | 287 (90) | 24 (67) | 311 (88) |

| Submucosa | 31 (10) | 12 (33) | 43 (12) |

| Synchronous tumor | |||

| Positive | 32 (12) | 2 (6) | 34 (78) |

| Negative | 247 (88) | 34 (94) | 281 (22) |

| Variables | Eradication Period (Years) | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <10, 198 Patients 223 Lesions | ≥10, 81 Patients 95 Lesions | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Age (years) | 0.250 | 1.43 (0.81–2.52) | 0.208 | ||

| <70 | 94 (47) | 33 (40) | |||

| ≥70 | 104 (53) | 48 (60) | |||

| Sex | 0.796 | 1.18 (0.56–2.49) | 0.613 | ||

| Male | 149 (75) | 62 (77) | |||

| Female | 49 (25) | 19 (23) | |||

| Smoking | 114 (57) | 58 (71) | 0.033 | 2.17 (1.11–4.22) | 0.023 |

| Gastric cancer family history | 59 (29) | 23 (28) | 0.788 | 0.96 (0.58–1.61) | 0.862 |

| Gastric mucosal atrophy | 0.031 | 1.82 (1.04–3.18) | 0.036 | ||

| Mild/moderate | 85 (43) | 46 (57) | |||

| Severe | 113 (57) | 35 (43) | |||

| Tumor size (mm) | 0.414 | 0.82 (0.58–1.35) | 0.709 | ||

| ≤10 | 118 (52) | 55 (58) | |||

| >10 | 105 (48) | 40 (42) | |||

| Tumor location | 0.011 | 1.53 (0.87–2.69) | 0.135 | ||

| Upper/middle | 140 (63) | 45 (47) | |||

| Lower | 83 (37) | 50 (53) | |||

| Macroscopic type | 0.136 | 0.73 (0.42–1.23) | 0.759 | ||

| Superficial elevated | 61 (27) | 34 (36) | |||

| Superficial depressed | 162 (73) | 61 (64) | |||

| Treatment | 0.261 | 1.38 (0.42–4.54) | 0.590 | ||

| Endoscopic resection | 203 (91) | 90 (95) | |||

| Surgical resection | 20 (9) | 5 (5) | |||

| Invasion depth | 0.178 | 1.41 (0.44–4.47) | 0.557 | ||

| Mucosa | 198 (89) | 89 (94) | |||

| Submucosa | 25 (11) | 6 (6) | |||

| Synchronous tumor | 0.410 | 0.77 (0.42–1.38) | 0.588 | ||

| Positive | 21 (11) | 11 (15) | |||

| Negative | 177 (89) | 70 (85) | |||

| Variables | Eradication Period (Years) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| <10, 28 Patients, 28 Lesions ≥10, Eight Patients, Eight Lesions | |||

| Age (years) | 0.485 | ||

| <70 | 21 (75) | 5 (63) | |

| ≥70 | 7 (25) | 3 (37) | |

| Sex | 0.858 | ||

| Male | 15 (54) | 4 (50) | |

| Female | 13 (46) | 4 (50) | |

| Smoking | 13 (46) | 3 (37) | 0.654 |

| Gastric cancer family history | 9 (32) | 4 (50) | 0.360 |

| Gastric mucosal atrophy | 0.698 | ||

| Mild/Moderate | 19 (68) | 6 (75) | |

| Severe | 9 (32) | 2 (25) | |

| Tumor size (mm) | 0.120 | ||

| ≤10 | 9 (32) | 5 (63) | |

| >10 | 19 (68) | 3 (37) | |

| Tumor location | 0.274 | ||

| Upper/Middle | 19 (68) | 7 (88) | |

| Lower | 9 (32) | 1 (12) | |

| Macroscopic type | 0.887 | ||

| Superficial elevated | 3 (11) | 1 (13) | |

| Superficial depressed | 25 (89) | 7 (87) | |

| Histological type | <0.01 | ||

| Differentiated mixed type | 3 (11) | 5 (63) | |

| Pure undifferentiated-type | 25 (89) | 3 (37) | |

| Treatment | 0.326 | ||

| Endoscopic resection | 16 (57) | 3 (38) | |

| Surgical resection | 12 (43) | 5 (62) | |

| Invasion depth | 0.776 | ||

| Mucosa | 19 (68) | 5 (63) | |

| Submucosa | 9 (32) | 3 (37) | |

| Synchronous tumor | 0.376 | ||

| Positive | 1 (3) | 1 (12) | |

| Negative | 27 (97) | 7 (88) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Teshima, H.; Kotachi, T.; Kuwai, T.; Tsuboi, A.; Tanaka, H.; Yamashita, K.; Takigawa, H.; Kishida, Y.; Urabe, Y.; Oka, S. Clinicopathologic Features of Early Gastric Cancer after Helicobacter pylori Eradication in Japanese Patients: Comparative Study between Early (<10 Years) and Late (>10 Years) Onset. Cancers 2024, 16, 3154. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16183154

Teshima H, Kotachi T, Kuwai T, Tsuboi A, Tanaka H, Yamashita K, Takigawa H, Kishida Y, Urabe Y, Oka S. Clinicopathologic Features of Early Gastric Cancer after Helicobacter pylori Eradication in Japanese Patients: Comparative Study between Early (<10 Years) and Late (>10 Years) Onset. Cancers. 2024; 16(18):3154. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16183154

Chicago/Turabian StyleTeshima, Hajime, Takahiro Kotachi, Toshio Kuwai, Akiyoshi Tsuboi, Hidenori Tanaka, Ken Yamashita, Hidehiko Takigawa, Yoshihiro Kishida, Yuji Urabe, and Shiro Oka. 2024. "Clinicopathologic Features of Early Gastric Cancer after Helicobacter pylori Eradication in Japanese Patients: Comparative Study between Early (<10 Years) and Late (>10 Years) Onset" Cancers 16, no. 18: 3154. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16183154

APA StyleTeshima, H., Kotachi, T., Kuwai, T., Tsuboi, A., Tanaka, H., Yamashita, K., Takigawa, H., Kishida, Y., Urabe, Y., & Oka, S. (2024). Clinicopathologic Features of Early Gastric Cancer after Helicobacter pylori Eradication in Japanese Patients: Comparative Study between Early (<10 Years) and Late (>10 Years) Onset. Cancers, 16(18), 3154. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16183154