Circulating Polymorphonuclear Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (PMN-MDSCs) Have a Biological Role in Patients with Primary Myelofibrosis

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Samples and Flow Cytometry Analysis of MDSCs

2.3. Detection of Proteins in Plasma

2.4. Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry on Spleen Sections

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Circulating PMN-MDSCs in Patients with PMF and CTRLs

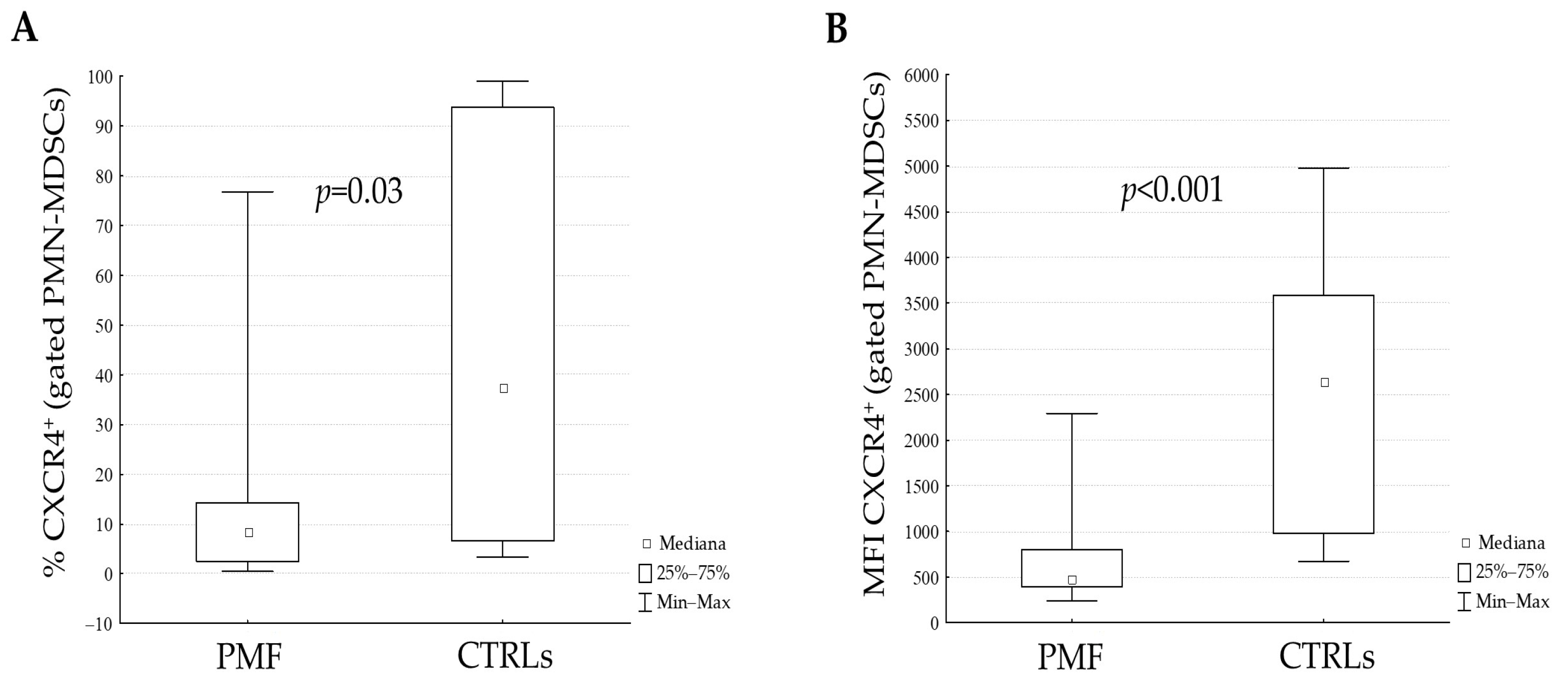

3.2. Plasma Levels of Proteins and Analysis of CXCR4 Receptor on PMN-MDSCs

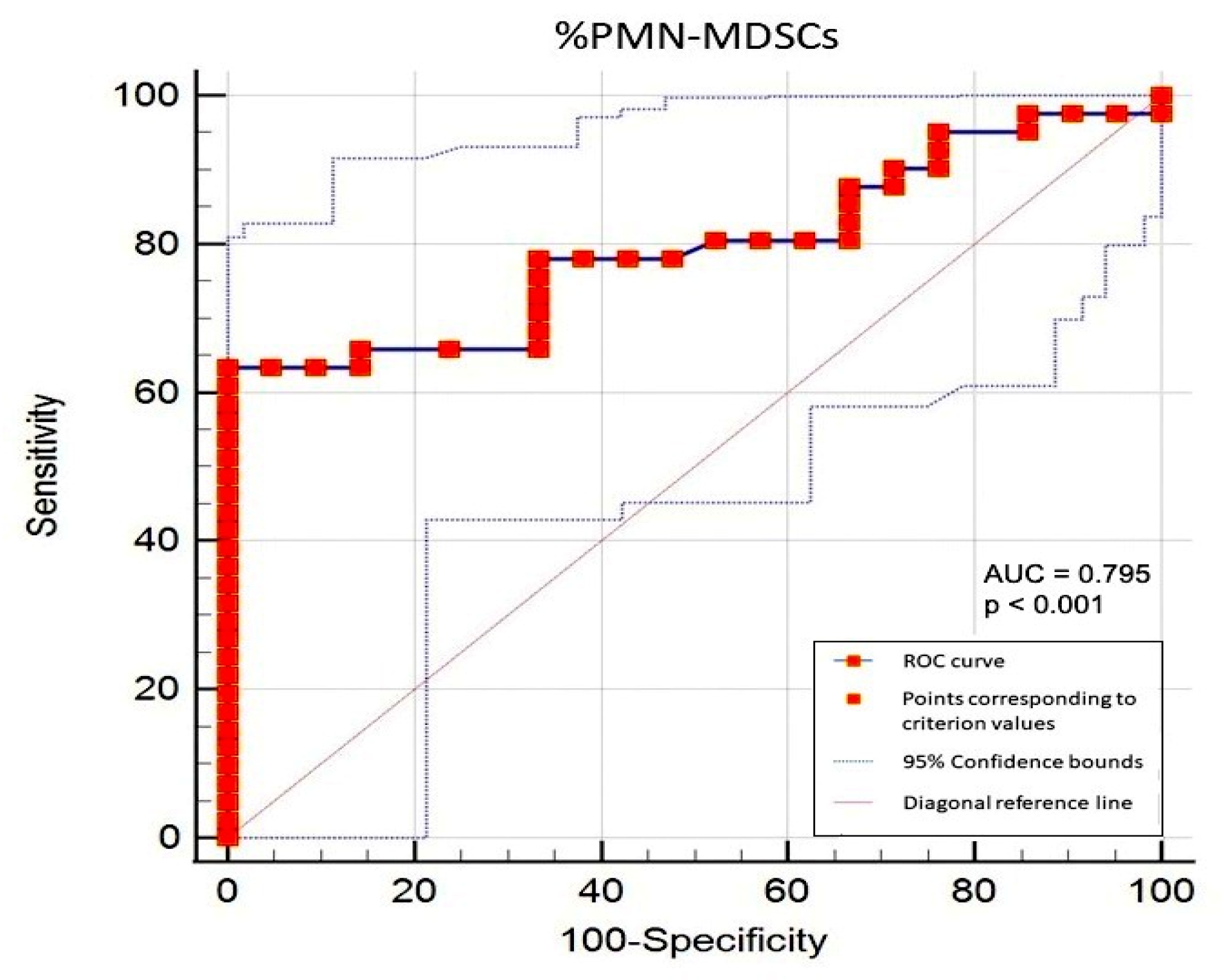

3.3. Correlations between Circulating PMN-MDSCs and Clinical/Biological Parameters in PMF Patients and Determination of the Cut-Off Value

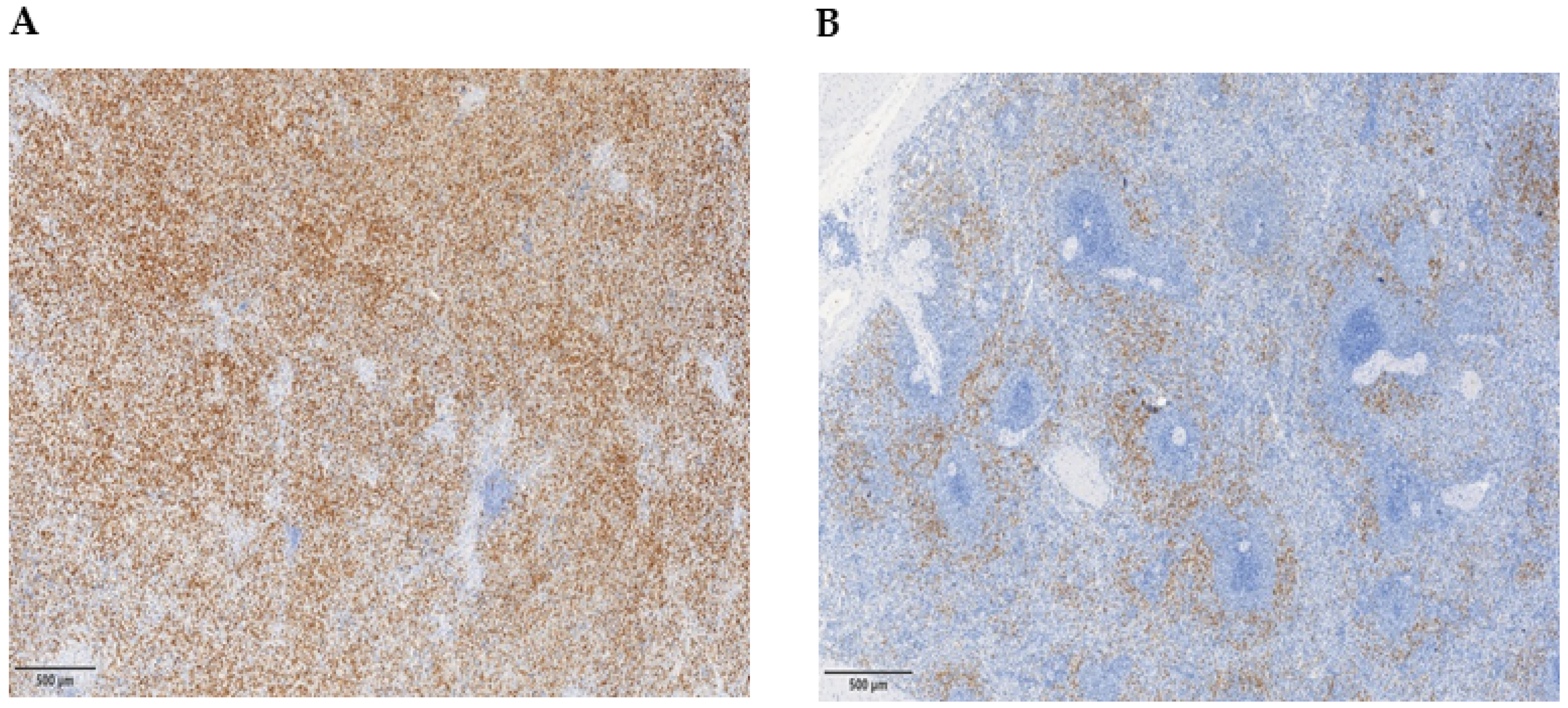

3.4. Myeloid Suppressor Cells in the Spleen of PMF Patients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gangat, N.; Tefferi, A. Myelofibrosis biology and contemporary management. Br. J. Haematol. 2020, 191, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tefferi, A. Primary myelofibrosis: 2023 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am. J. Hematol. 2023, 98, 801–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koschmieder, S.; Chatain, N. Role of inflammation in the biology of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood Rev. 2020, 42, 100711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbui, T.; Carobbio, A.; Finazzi, G.; Guglielmelli, P.; Salmoiraghi, S.; Rosti, V.; Rambaldi, A.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Barosi, G. Elevated C-reactive protein is associated with shortened leukemia-free survival in patients with myelofibrosis. Leukemia 2013, 27, 2084–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabrilovich, D.I.; Nagaraj, S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consonni, F.M.; Porta, C.; Marino, A.; Pandolfo, C.; Mola, S.; Bleve, A.; Sica, A. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells: Ductile Targets in Disease. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veglia, F.; Sanseviero, E.; Gabrilovich, D.I. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the era of increasing myeloid cell diversity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, X.; Wu, S.; Cui, D.; Xu, Z. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: Key immunosuppressive regulators and therapeutic targets in hematological malignancies. Biomark. Res. 2023, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veglia, F.; Perego, M.; Gabrilovich, D. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells coming of age. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.F.; Song, S.Y.; Wang, T.J.; Ji, W.J.; Li, S.W.; Liu, N.; Yan, C.X. Prognostic role of pretreatment circulating MDSCs in patients with solid malignancies: A meta-analysis of 40 studies. Oncoimmunology 2018, 7, e1494113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Patel, S.; Tcyganov, E.; Gabrilovich, D.I. The Nature of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2016, 37, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groth, C.; Weber, R.; Lasser, S.; Özbay, F.G.; Kurzay, A.; Petrova, V.; Altevogt, P.; Utikal, J.; Umansky, V. Tumor promoting capacity of polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells and their neutralization. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 149, 1628–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.C.; Kundra, A.; Andrei, M.; Baptiste, S.; Chen, C.; Wong, C.; Sindhu, H. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasm. Leuk. Res. 2016, 43, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapor, S.; Momčilović, S.; Mojsilović, S.; Radojković, M.; Apostolović, M.; Filipović, B.; Gotić, M.; Čokić, V.; Santibanez, J.F. Increase in Frequency of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in the Bone Marrow of Myeloproliferative Neoplasm: Potential Implications in Myelofibrosis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2023, 1408, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonometti, A.; Borsani, O.; Rumi, E.; Ferretti, V.V.; Dioli, C.; Lucato, E.; Paulli, M.; Boveri, E. Arginase-1+ bone marrow myeloid cells are reduced in myeloproliferative neoplasms and correlate with clinical phenotype, fibrosis, and molecular driver. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 7815–7822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronte, V.; Brandau, S.; Chen, S.H.; Colombo, M.P.; Frey, A.B.; Greten, T.F.; Mandruzzato, S.; Murray, P.J.; Ochoa, A.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S.; et al. Recommendations for myeloid-derived suppressor cell nomenclature and characterization standards. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.; Thiele, J.; Borowitz, M.J.; Le Beau, M.M.; Bloomfield, C.D.; Cazzola, M.; Vardiman, J.W. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood 2016, 127, 462–463, Erratum in Blood 2016, 127, 2391–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschoor, C.P.; Johnstone, J.; Millar, J.; Dorrington, M.G.; Habibagahi, M.; Lelic, A.; Loeb, M.; Bramson, J.L.; Bowdish, D.M. Blood CD33(+)HLA-DR(-) myeloid-derived suppressor cells are increased with age and a history of cancer. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2013, 93, 633–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condamine, T.; Dominguez, G.A.; Youn, J.I.; Kossenkov, A.V.; Mony, S.; Alicea-Torres, K.; Tcyganov, E.; Hashimoto, A.; Nefedova, Y.; Lin, C.; et al. Lectin-type oxidized LDL receptor-1 distinguishes population of human polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer patients. Sci. Immunol. 2016, 1, aaf8943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medinger, M.; Skoda, R.; Gratwohl, A.; Theocharides, A.; Buser, A.; Heim, D.; Dirnhofer, S.; Tichelli, A.; Tzankov, A. Angiogenesis and vascular endothelial growth factor-/receptor expression in myeloproliferative neoplasms: Correlation with clinical parameters and JAK2-V617F mutational status. Br. J. Haematol. 2009, 146, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, N.J.; Schisterman, E.F. The inconsistency of “optimal” cutpoints obtained using two criteria based on the receiver operating characteristic curve. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 163, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barosi, G.; Rosti, V.; Catarsi, P.; Villani, L.; Abbà, C.; Carolei, A.; Magrini, U.; Gale, R.P.; Massa, M.; Campanelli, R. Reduced CXCR4-expression on CD34-positive blood cells predicts outcomes of persons with primary myelofibrosis. Leukemia 2021, 35, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, L.J.H.; Petersen, J.E.V.; Eugen-Olsen, J. Soluble Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor (suPAR) as a Biomarker of Systemic Chronic Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 780641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; DeBusk, L.M.; Fukuda, K.; Fingleton, B.; Green-Jarvis, B.; Shyr, Y.; Matrisian, L.M.; Carbone, D.P.; Lin, P.C. Expansion of myeloid immune suppressor Gr+CD11b+ cells in tumor-bearing host directly promotes tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell 2004, 6, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murdoch, C.; Muthana, M.; Coffelt, S.B.; Lewis, C.E. The role of myeloid cells in the promotion of tumour angiogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 618–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabrilovich, D.I. The Dawn of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells: Identification of Arginase I as the Mechanism of Immune Suppression. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 3953–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergenfelz, C.; Leandersson, K. The Generation and Identity of Human Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youn, J.I.; Collazo, M.; Shalova, I.N.; Biswas, S.K.; Gabrilovich, D.I. Characterization of the nature of granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2012, 91, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, H.K.; Donskov, F.; Marcussen, N.; Nordsmark, M.; Lundbeck, F.; von der Maase, H. Presence of intratumoral neutrophils is an independent prognostic factor in localized renal cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 4709–4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, T.O.; Schmidt, H.; Møller, H.J.; Donskov, F.; Høyer, M.; Sjoegren, P.; Christensen, I.J.; Steiniche, T. Intratumoral neutrophils and plasmacytoid dendritic cells indicate poor prognosis and are associated with pSTAT3 expression in AJCC stage I/II melanoma. Cancer 2012, 118, 2476–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, H.L.; Chen, J.W.; Li, M.; Xiao, Y.B.; Fu, J.; Zeng, Y.X.; Cai, M.Y.; Xie, D. Increased intratumoral neutrophil in colorectal carcinomas correlates closely with malignant phenotype and predicts patients’ adverse prognosis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.W.; Qiu, S.J.; Fan, J.; Zhou, J.; Gao, Q.; Xiao, Y.S.; Xu, Y.F. Intratumoral neutrophils: A poor prognostic factor for hepatocellular carcinoma following resection. J. Hepatol. 2011, 54, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trellakis, S.; Bruderek, K.; Dumitru, C.A.; Gholaman, H.; Gu, X.; Bankfalvi, A.; Scherag, A.; Hütte, J.; Dominas, N.; Lehnerdt, G.F.; et al. Polymorphonuclear granulocytes in human head and neck cancer: Enhanced inflammatory activity, modulation by cancer cells and expansion in advanced disease. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 129, 2183–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, L.; Montes-Servín, E.; Hernandez-Martinez, J.M.; Orozco-Morales, M.; Michel-Tello, D.; Morales-Flores, R.A.; Flores-Estrada, D.; Arrieta, O. Levels of peripheral blood polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells and selected cytokines are potentially prognostic of disease progression for patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2018, 67, 1393–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahr, A.A.; Salama, M.E.; Carreau, N.; Tremblay, D.; Verstovsek, S.; Mesa, R.; Hoffman, R.; Mascarenhas, J. Bone marrow fibrosis in myelofibrosis: Pathogenesis, prognosis and targeted strategies. Haematologica 2016, 101, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obermajer, N.; Muthuswamy, R.; Odunsi, K.; Edwards, R.P.; Kalinski, P. PGE(2)-induced CXCL12 production and CXCR4 expression controls the accumulation of human MDSCs in ovarian cancer environment. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 7463–7470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Lai, L.; Chen, Q.; Song, Y.; Xu, S.; Ma, F.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Yu, H.; Cao, X.; et al. MicroRNA-494 is required for the accumulation and functions of tumor-expanded myeloid-derived suppressor cells via targeting of PTEN. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 5500–5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Ge, J.; Guo, Y.; Wang, B.; Huang, Y.; Yang, T.; et al. SDF-1/CXCR4 axis facilitates myeloid-derived suppressor cells accumulation in osteosarcoma microenvironment and blunts the response to anti-PD-1 therapy. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 75, 105818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Clavijo, P.E.; Robbins, Y.; Patel, P.; Friedman, J.; Greene, S.; Das, R.; Silvin, C.; Van Waes, C.; Horn, L.A.; et al. Inhibiting myeloid-derived suppressor cell trafficking enhances T cell immunotherapy. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e126853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Cheng, J.; Fu, B.; Liu, W.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, Y. Hepatic carcinoma-associated fibroblasts enhance immune suppression by facilitating the generation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncogene 2017, 36, 1090–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittang, A.O.; Kordasti, S.; Sand, K.E.; Costantini, B.; Kramer, A.M.; Perezabellan, P.; Seidl, T.; Rye, K.P.; Hagen, K.M.; Kulasekararaj, A.; et al. Expansion of myeloid derived suppressor cells correlates with number of T regulatory cells and disease progression in myelodysplastic syndrome. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1062208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canè, S.; Bronte, V. Detection and functional evaluation of arginase-1 isolated from human PMNs and murine MDSC. Methods Enzymol. 2020, 632, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, P.C.; Ochoa, A.C. Arginine regulation by myeloid derived suppressor cells and tolerance in cancer: Mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Immunol. Rev. 2008, 222, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Primary Myelofibrosis (PMF) (PMF) | Controls (CTRLs) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 41 | 21 |

| Age (years), median (range) | 54 (36–83) | 58 (28–90) |

| Out of therapy, number (percent) | 15 (36.5%) | 21 (100%) |

| In therapy, number | ||

| 17 | 0 |

| 9 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 |

| Survival *, number (percent) | 37 (90.2%) | na |

| PMF clinical–hematological characteristics | ||

| Hemoglobin (g/L), median (range) | 124 (80–157) | |

| White-blood cell count (×109/L), median (range) | 8 (2–39.6) | |

| Platelet count (×109/L), median (range) | 430 (38–1400) | |

| LDH # (mU/mL), median (range) | 299 (127–1322) | |

| Blasts @, number of PMF (percent) | ||

| 32 (91.5%) | |

| 1 (2.8%) | |

| 2 (5.7%) | |

| CD34+ absolute number/µL, median (range) | 7.6 (0.6–2855) | |

| PMF biological and molecular characteristics | ||

| Bone marrow (BM) fibrosis, number (percent) | ||

| 24 (58.5%) | |

| 17 (41.5%) | |

| Spleen size (cm), median (range) | 120 (90–437) | |

| JAK2V617F mutation, number (percent) | 27 (65.8%) | |

| CALR mutation, number (percent) | 14 (34.2%) | |

| PMF | CTRLs | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCL2 | 123.6 (17.6–282) | 159 (73.9–212) | NS |

| CXCL5 | 163 (15.4–1073) | 173 (37.4–1076 | NS |

| FGF2 | 4.2 (<0.5 to 10.9) | <0.5 (<0.5 to 9.2) | 0.002 |

| IL-1β | <5.9 (<5.9 to 35.1) | <5.9 (<0.5 to 9.3) | NS |

| IL-6 | 1.3 (<0.4 to 29.3) | <0.4 (<0.4 to 1.3) | <0.001 |

| IL-8 | 4.5 (<1.3 to 34.4) | 1.9 (<1.3 to 6.7) | NS |

| TNF-α | 6.5 (<2.4 to 31.5) | <2.4 (<2.4 to 3.4) | <0.001 |

| VEGF | 26.2 (3.9–140) | 5.8 (4.3–22.3) | <0.001 |

| SDF-1α | 2155 (1313–3325) | 1730 (1145–2606) | 0.02 |

| n | R | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % CD34+ | 41 | 0.403 | 0.01 |

| CD34 absolute number/µL | 38 | 0.566 | <0.001 |

| WBC count (×109/L) | 39 | 0.410 | 0.01 |

| LDH (mU/mL) | 29 | 0.463 | 0.01 |

| Hb level (g/L) | 39 | −0.419 | <0.01 |

| Plt count (×109/L) | 39 | −0.353 | 0.03 |

| % CXCR4+ (on gated CD34+) | 41 | −0.485 | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Campanelli, R.; Carolei, A.; Catarsi, P.; Abbà, C.; Boveri, E.; Paulli, M.; Gentile, R.; Morosini, M.; Albertini, R.; Mantovani, S.; et al. Circulating Polymorphonuclear Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (PMN-MDSCs) Have a Biological Role in Patients with Primary Myelofibrosis. Cancers 2024, 16, 2556. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16142556

Campanelli R, Carolei A, Catarsi P, Abbà C, Boveri E, Paulli M, Gentile R, Morosini M, Albertini R, Mantovani S, et al. Circulating Polymorphonuclear Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (PMN-MDSCs) Have a Biological Role in Patients with Primary Myelofibrosis. Cancers. 2024; 16(14):2556. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16142556

Chicago/Turabian StyleCampanelli, Rita, Adriana Carolei, Paolo Catarsi, Carlotta Abbà, Emanuela Boveri, Marco Paulli, Raffaele Gentile, Monica Morosini, Riccardo Albertini, Stefania Mantovani, and et al. 2024. "Circulating Polymorphonuclear Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (PMN-MDSCs) Have a Biological Role in Patients with Primary Myelofibrosis" Cancers 16, no. 14: 2556. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16142556

APA StyleCampanelli, R., Carolei, A., Catarsi, P., Abbà, C., Boveri, E., Paulli, M., Gentile, R., Morosini, M., Albertini, R., Mantovani, S., Massa, M., Barosi, G., & Rosti, V. (2024). Circulating Polymorphonuclear Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (PMN-MDSCs) Have a Biological Role in Patients with Primary Myelofibrosis. Cancers, 16(14), 2556. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16142556