Psychosocial Impact of Virtual Cancer Care through Technology: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Does telemedicine, compared to in-person care, negatively affect patient psychosocial health in adult cancer patients?

- Do the psychosocial effects of the interventions change according to the phase of care (active treatment vs. follow-up)?

- Are there differences in the size of the effects based on the type of cancer?

- What modes of intervention delivery work best?

2. Methods

2.1. Overview

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias (Quality) Assessment

2.6. Assessment of Reporting Biases

2.7. Data Synthesis

2.8. Subgroup Analysis and Investigation of Heterogeneity

3. Results

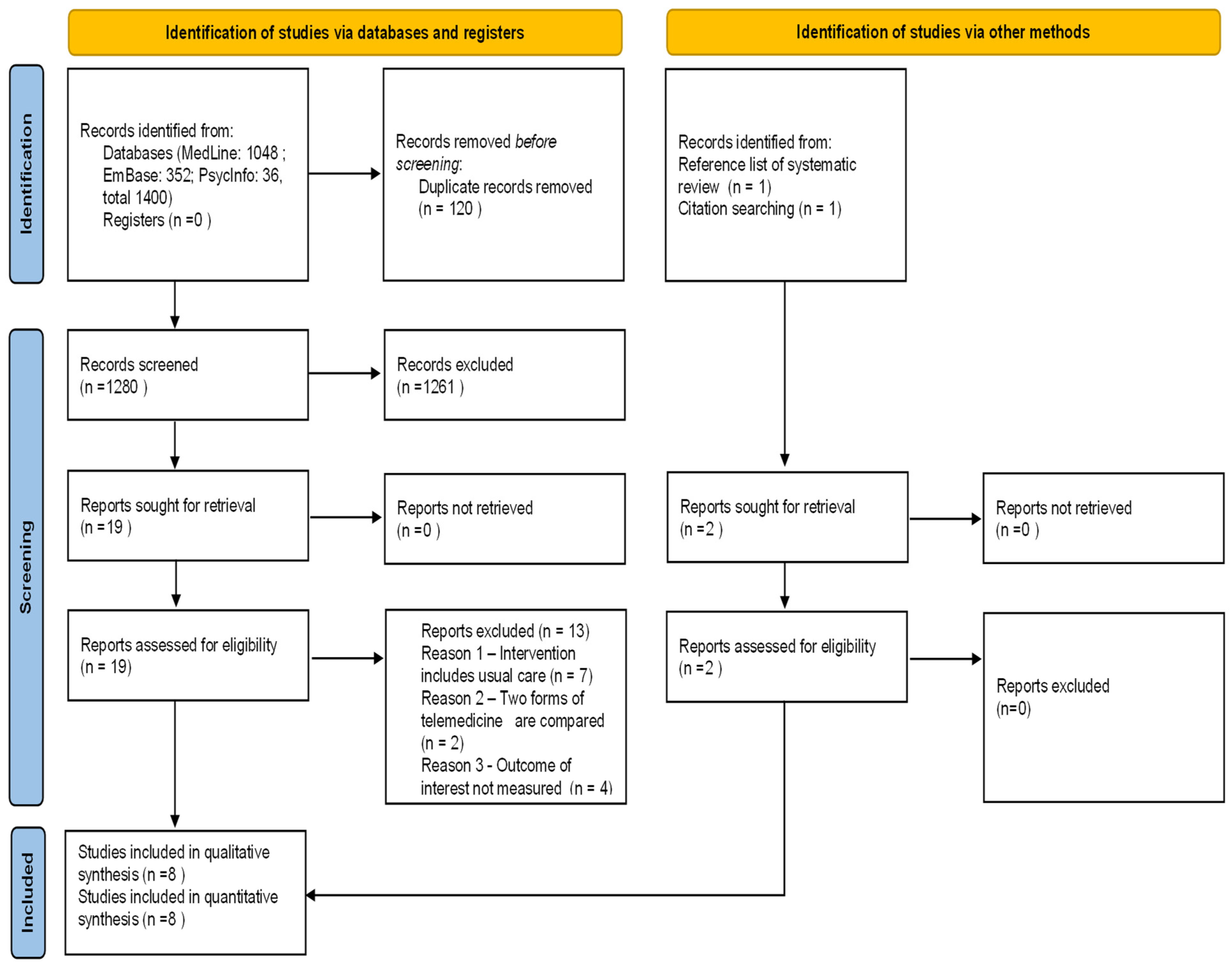

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

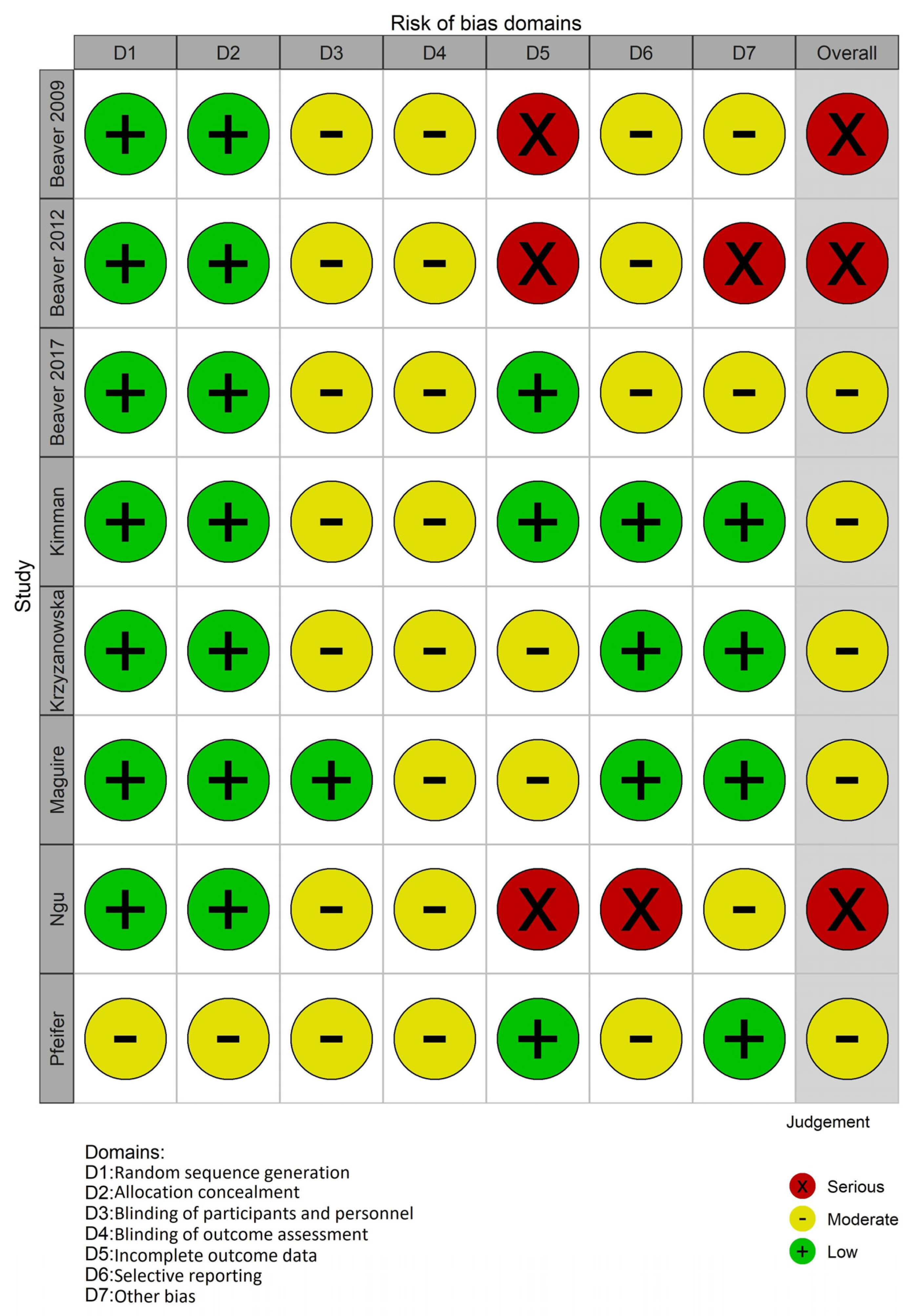

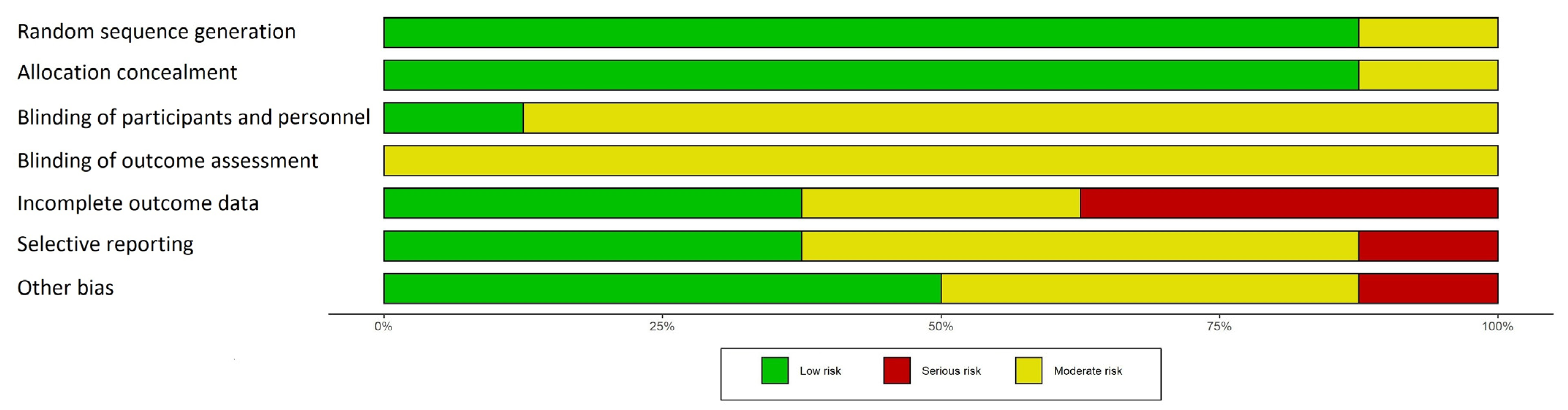

3.3. Risk of Bias in Studies

- Randomization process

- Allocation concealment

- Blinding of participants and personnel

- Blinding of outcome assessment

- Incomplete outcome data

- Selective reporting

- Other potential sources of bias

3.4. Effects of Interventions

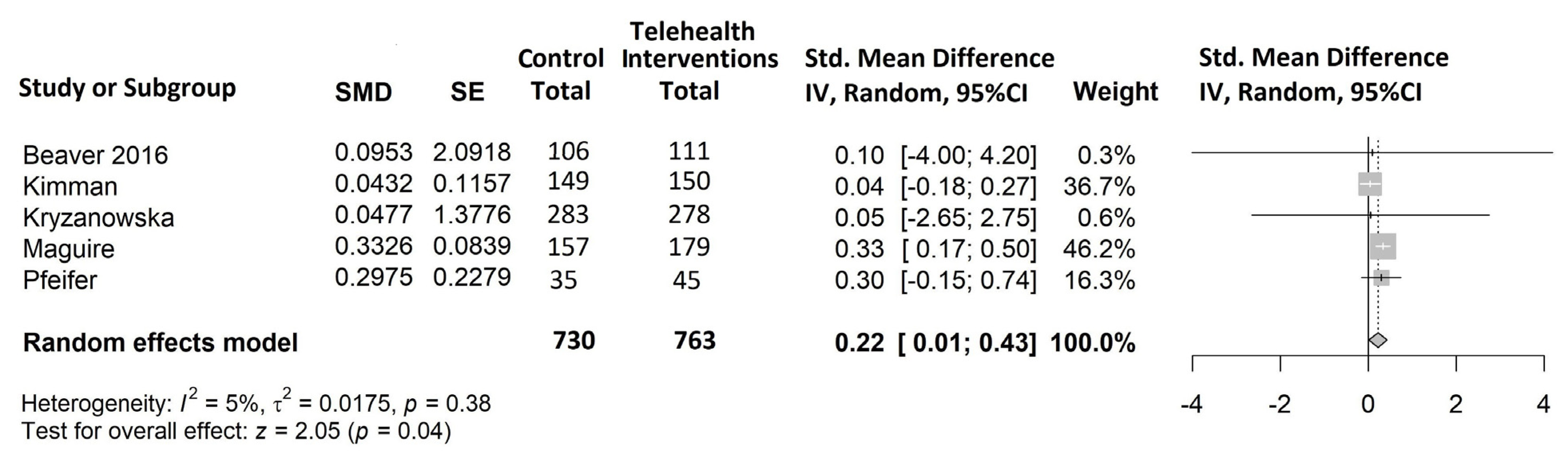

- Quality of Life (Figure 4)

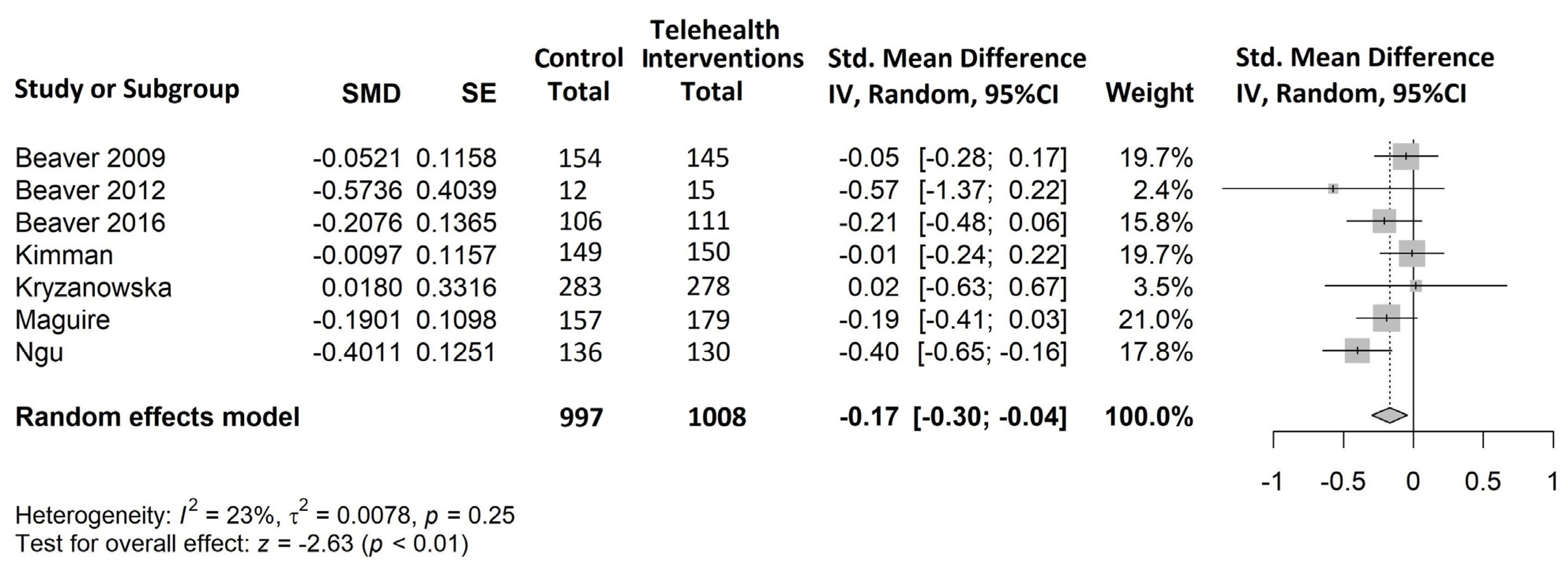

- Anxiety (Figure 5)

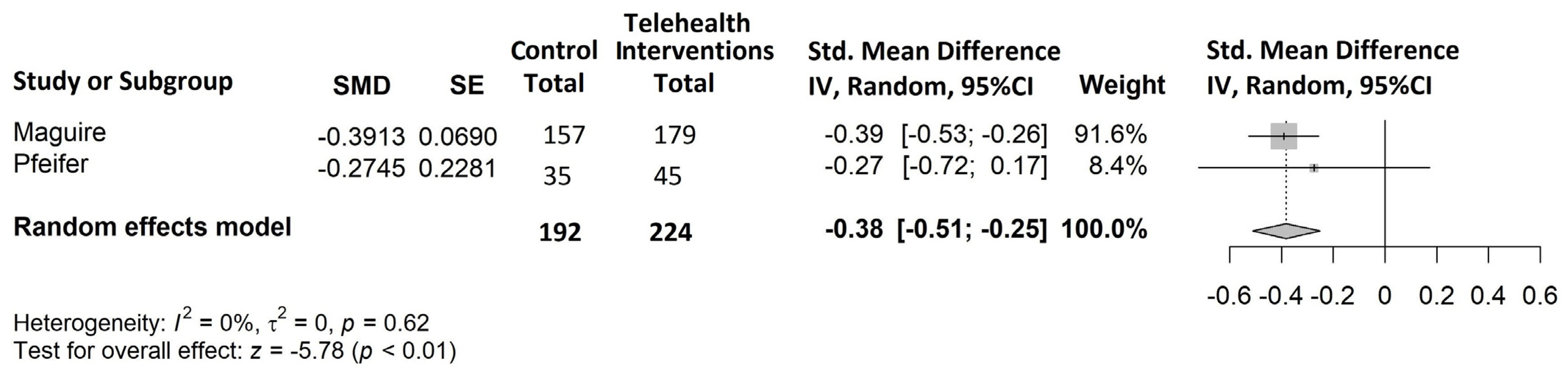

- Global distress (Figure 6)

- Depression

3.5. Subgroup Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Effectiveness of Telehealth Interventions

4.2. Subgroup Analysis

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Methods Followed for Risk of Bias Assessment

- Selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment).

- Performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel).

- Detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment).

- Attrition bias (incomplete outcome data).

- Reporting bias (selective reporting of outcomes).

- Other possible sources of bias (serious issues not captured within the other bias domains such as contamination or inconsistencies with timing of interventions/comparisons).

References

- Singh, S.; Fletcher, G.G.; Yao, X.; Sussman, J. Virtual Care in Patients with Cancer: A Systematic Review. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 3488–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, S.; Lee, T.H. In-Person Health Care as Option B. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinar, P.; Kubal, T.; Freifeld, A.; Mishra, A.; Shulman, L.; Bachman, J.; Fonseca, R.; Uronis, H.; Klemanski, D.; Slusser, K.; et al. Safety at the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic: How to Keep Our Oncology Patients and Healthcare Workers Safe. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2020, 18, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakitas, M.; Cheville, A.L.; Mulvey, T.M.; Peppercorn, J.; Watts, K.; Dionne-Odom, J.N. Telehealth Strategies to Support Patients and Families Across the Cancer Trajectory. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2021, 41, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, W.; Guan, W.; Chen, R.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Xu, K.; Li, C.; Ai, Q.; Lu, W.; Liang, H.; et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: A nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Ouyang, W.; Chua, M.L.K.; Xie, C. SARS-CoV-2 Transmission in Patients With Cancer at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 1108–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, A.S.; Schiaffino, M.K.; Nalawade, V.; Aziz, L.; Pacheco, F.V.; Nguyen, B.; Vu, P.; Patel, S.P.; Martinez, M.E.; Murphy, J.D. Disparities in telemedicine during COVID-19. Cancer Med. 2022, 11, 1192–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodin, D.; Lovas, M.; Berlin, A. The reality of virtual care: Implications for cancer care beyond the pandemic. Healthcare 2020, 8, 100480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.; Lucas, G.; Marcu, A.; Piano, M.; Grosvenor, W.; Mold, F.E.; Maguire, R.; Ream, E. Cancer Survivors’ Experience With Telehealth: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agochukwu, N.Q.; Skolarus, T.A.; Wittmann, D. Telemedicine and prostate cancer survivorship: A narrative review. mHealth 2018, 4, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, A.; Serhal, E. Digital Health Equity and COVID-19: The Innovation Curve Cannot Reinforce the Social Gradient of Health. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemp, E.; Trigg, J.; Beatty, L.; Christensen, C.; Dhillon, H.M.; Maeder, A.; Williams, P.A.H.; Koczwara, B. Health literacy, digital health literacy and the implementation of digital health technologies in cancer care: The need for a strategic approach. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2021, 32, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, S.; Hurwitz, H.M.; Mercer, M.B.; Hizlan, S.; Gali, K.; Yu, P.-C.; Franke, C.; Martinez, K.; Stanton, M.; Faiman, M.; et al. Patient Experience in Virtual Visits Hinges on Technology and the Patient-Clinician Relationship: A Large Survey Study With Open-ended Questions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e18488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, R.; Nanni, M.G.; Riba, M.B.; Sabato, S.; Grassi, L. The burden of psychosocial morbidity related to cancer: Patient and family issues. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2017, 29, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, M.; Gräfenstein, L.; Karnosky, J.; Schulz, C.; Koller, M. Psychosocial Burden and Quality of Life of Lung Cancer Patients: Results of the EORTC QLQ-C30/QLQ-LC29 Questionnaire and Hornheide Screening Instrument. Cancer Manag. Res. 2021, 13, 6191–6197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.-M.; Rafiemanesh, H.; Aghamohammadi, T.; Badakhsh, M.; Amirshahi, M.; Sari, M.; Behnamfar, N.; Roudini, K. Prevalence of anxiety among breast cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer 2020, 27, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.D.; Young, J.M.; Price, M.A.; Butow, P.N.; Solomon, M. What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2009, 17, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, R.; Hall, S.; Sinclair, J.E.; Bond, C.; Murchie, P. Using technology to deliver cancer follow-up: A systematic review. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-Y.; Guan, B.-S.; Li, Z.-K.; Li, X.-Y. Effect of telehealth intervention on breast cancer patients’ quality of life and psychological outcomes: A meta-analysis. J. Telemed. Telecare 2018, 24, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, J.L.; Rosen, A.; Wilson, F.A. The Effect of Telehealth Interventions on Quality of Life of Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Telemed. E-Health 2018, 24, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, J.L.; Rosen, A.B.; Wilson, F.A. The effect of telehealth interventions on quality of life of cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Inform. J. 2020, 26, 1060–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, L.; Liu, Z.; Lin, S.; Liu, Z.; Liu, H.; Mai, Z.; Liu, Z.; Chen, C.; Zhao, Q. The effects of telemedicine on the quality of life of patients with lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2020, 11, 2040622320961597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buneviciene, I.; Mekary, R.A.; Smith, T.R.; Onnela, J.-P.; Bunevicius, A. Can mHealth interventions improve quality of life of cancer patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2021, 157, 103123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Peng, X.; Hu, X. Effect of telehealth interventions on quality of life in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 122, 103970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, H.E.C.; Santos, G.N.M.; Leite, A.F.; Mesquita, C.R.M.; Figueiredo, P.T.D.S.; Stefani, C.M.; Melo, N.D.S. The feasibility of telehealth in the monitoring of head and neck cancer patients: A systematic review on remote technology, user adherence, user satisfaction, and quality of life. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 8391–8404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleman, A.; Vijenthira, A.; Berlin, A.; Prica, A.; Rodin, D. The Use of Virtual Care in Patients with Hematologic Malignancies: A Scoping Review. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 892–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, A.C.; Raeside, R.; Hyun, K.K.; Partridge, S.R.; Di Tanna, G.L.; Hafiz, N.; Tu, Q.; Tat-Ko, J.; Sum, S.C.M.; Sherman, K.A.; et al. Electronic Health Interventions for Patients With Breast Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 2257–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Dong, N.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S. Effect of telehealth interventions on anxiety and depression in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Telemed. Telecare 2022, 1357633X221122727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminiti, C.; Diodati, F.; Annunziata, M.A.; Di Giulio, P.; Isa, L.; Mosconi, P.; Nanni, M.G.; Patrini, A.; Piredda, M.; Santangelo, C.; et al. Psychosocial Care for Adult Cancer Patients: Guidelines of the Italian Medical Oncology Association. Cancers 2021, 13, 4878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PROSPERO. International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO). Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayyan. Intelligent Systematic Review. Available online: https://www.rayyan.ai/ (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Version 6.3 (Updated February 2022); Cochrane: London, UK, 2022; Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Sutton, A.J.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Terrin, N.; Jones, D.R.; Lau, J.; Carpenter, J.; Rücker, G.; Harbord, R.M.; Schmid, C.H.; et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis in the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Hillsdale, N.J., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Absolom, K.; Warrington, L.; Hudson, E.; Hewison, J.; Morris, C.; Holch, P.; Carter, R.; Gibson, A.; Holmes, M.; Clayton, B.; et al. Phase III Randomized Controlled Trial of eRAPID: eHealth Intervention During Chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 734–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouleftour, W.; Muron, T.; Guillot, A.; Tinquaut, F.; Rivoirard, R.; Jacquin, J.-P.; Saban-Roche, L.; Boussoualim, K.; Tavernier, E.; Augeul-Meunier, K.; et al. Effectiveness of a nurse-led telephone follow-up in the therapeutic management of patients receiving oral antineoplastic agents: A randomized, multicenter controlled trial (ETICCO study). Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 4257–4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjell, M.; Langius-Eklöf, A.; Nilsson, M.; Wengström, Y.; Sundberg, K. Reduced symptom burden with the support of an interactive app during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer—A randomized controlled trial. Breast 2020, 51, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hass, H.G.; Muthny, F.; Stepien, J.; Lerch, J.; von der Marwitz, C.; Schröck, R.; Berger, D.; Tripp, J. Effekte der telefonischen Nachsorge in der onkologischen Rehabilitation nach Brustkrebs–Ergebnisse einer randomisierten Studie. Die Rehabil. 2017, 56, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, P.D.; Schers, H.J.; Bronkhorst, E.M.; Vissers, K.C.P.; Hasselaar, J.G.J. The effect of weekly specialist palliative care teleconsultations in patients with advanced cancer–A randomized clinical trial. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traeger, L.; McDonnell, T.M.; McCarty, C.E.; Greer, J.A.; El-Jawahri, A.; Temel, J.S. Nursing intervention to enhance outpatient chemotherapy symptom management: Patient-reported outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Cancer 2015, 121, 3905–3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walle, T.; Erdal, E.; Mühlsteffen, L.; Singh, H.M.; Gnutzmann, E.; Grün, B.; Hofmann, H.; Ivanova, A.; Köhler, B.C.; Korell, F.; et al. Completion rate and impact on physician–patient relationship of video consultations in medical oncology: A randomised controlled open-label trial. ESMO Open 2020, 5, e000912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheelock, A.E.; Bock, M.A.; Martin, E.L.; Hwang, J.; Ernest, M.L.; Rugo, H.S.; Esserman, L.J.; Melisko, M.E. SIS.NET: A randomized controlled trial evaluating a web-based system for symptom management after treatment of breast cancer. Cancer 2015, 121, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yount, S.E.; Rothrock, N.; Bass, M.; Beaumont, J.L.; Pach, D.; Lad, T.; Patel, J.; Corona, M.; Weiland, R.; Del Ciello, K.; et al. A Randomized Trial of Weekly Symptom Telemonitoring in Advanced Lung Cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2014, 47, 973–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.-E.; Wong, F.K.Y.; You, L.-M.; Zheng, M.-C.; Li, Q.; Zhang, B.-Y.; Huang, M.-R.; Ye, X.-M.; Liang, M.-J.; Liu, J.-L. Effects of Enterostomal Nurse Telephone Follow-up on Postoperative Adjustment of Discharged Colostomy Patients. Cancer Nurs. 2013, 36, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yang, L.; Hua, Z. Effect of Remote Internet Follow-Up on Postradiotherapy Compliance Among Patients with Esophageal Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Study. Telemed. E-Health 2015, 21, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viers, B.R.; Lightner, D.J.; Rivera, M.E.; Tollefson, M.K.; Boorjian, S.A.; Karnes, R.J.; Thompson, R.H.; O’Neil, D.A.; Hamilton, R.L.; Gardner, M.R.; et al. Efficiency, Satisfaction, and Costs for Remote Video Visits Following Radical Prostatectomy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. Urol. 2015, 68, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooney, K.H.; Beck, S.L.; Wong, B.; Dunson, W.; Wujcik, D.; Whisenant, M.; Donaldson, G. Automated home monitoring and management of patient-reported symptoms during chemotherapy: Results of the symptom care at home RCT. Cancer Med. 2017, 6, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaver, K.; Tysver-Robinson, D.; Campbell, M.; Twomey, M.; Williamson, S.; Hindley, A.; Susnerwala, S.; Dunn, G.; Luker, K. Comparing hospital and telephone follow-up after treatment for breast cancer: Randomised equivalence trial. BMJ 2009, 338, a3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaver, K.; Campbell, M.; Williamson, S.; Procter, D.; Sheridan, J.; Heath, J.; Susnerwala, S. An exploratory randomized controlled trial comparing telephone and hospital follow-up after treatment for colorectal cancer. Color. Dis. 2012, 14, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimman, M.; Dirksen, C.; Voogd, A.; Falger, P.; Gijsen, B.; Thuring, M.; Lenssen, A.; van der Ent, F.; Verkeyn, J.; Haekens, C.; et al. Nurse-led telephone follow-up and an educational group programme after breast cancer treatment: Results of a 2 × 2 randomised controlled trial. Eur. J. Cancer 2011, 47, 1027–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyzanowska, M.K.; A Julian, J.; Gu, C.-S.; Powis, M.; Li, Q.; Enright, K.; Howell, D.; Earle, C.C.; Gandhi, S.; Rask, S.; et al. Remote, proactive, telephone based management of toxicity in outpatients during adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy for early stage breast cancer: Pragmatic, cluster randomised trial. BMJ 2021, 375, e066588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, R.; McCann, L.; Kotronoulas, G.; Kearney, N.; Ream, E.; Armes, J.; Patiraki, E.; Furlong, E.; Fox, P.; Gaiger, A.; et al. Real time remote symptom monitoring during chemotherapy for cancer: European multicentre randomised controlled trial (eSMART). BMJ 2021, 374, n1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, M.P.; Keeney, C.; Bumpous, J.; Schapmire, T.J.; Studts, J.L.; Myers, J.; Head, B. Impact of a telehealth intervention on quality of life and symptom distress in patients with head and neck cancer. J. Community Support. Oncol. 2015, 13, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaver, K.; Williamson, S.; Sutton, C.; Hollingworth, W.; Gardner, A.; Allton, B.; Abdel-Aty, M.; Blackwood, K.; Burns, S.; Curwen, D.; et al. Comparing hospital and telephone follow-up for patients treated for stage-I endometrial cancer (ENDCAT trial): A randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority trial. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017, 124, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngu, S.; Wei, N.; Li, J.; Chu, M.M.Y.; Tse, K.Y.; Ngan, H.Y.S.; Chan, K.K.L. Nurse-led follow-up in survivorship care of gynaecological malignancies—A randomised controlled trial. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2020, 29, e13325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.F.; Sussman, J.; Kent, D.M.; Hayward, R.A. Three simple rules to ensure reasonably credible subgroup analyses. BMJ 2015, 351, h5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminiti, C.; Iezzi, E.; Passalacqua, R. Effectiveness of the HuCare Quality Improvement Strategy on health-related quality of life in patients with cancer: Study protocol of a stepped-wedge cluster randomised controlled trial (HuCare2 study). BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; Yeung, J.C.; Bolger, J.C. The safety and acceptability of using telehealth for follow-up of patients following cancer surgery: A systematic review. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 49, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, R.; Crichton, M.; Crawford-Williams, F.; Agbejule, O.; Yu, K.; Hart, N.; Alves, F.D.A.; Ashbury, F.; Eng, L.; Fitch, M.; et al. The efficacy, challenges, and facilitators of telemedicine in post-treatment cancer survivorship care: An overview of systematic reviews. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 1552–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author | Year | Single-Center or Multicenter | Country | No. Patients Randomized and Analyzed in the Meta-Analysis | Age (Years) | Sex (% Female) | Cancer Types | Phase of Care | Intervention vs. Control | Intervention Delivery Method | Outcome of Interest and Instrument: Distress | Outcome of Interest and Instrument: Anxiety | Outcome of Interest and Instrument: Depression | Outcome of Interest and Instrument: Quality of Life |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beaver [50] | 2009 | Multicenter | United Kingdom | 374 randomized (145 intervention arm vs. 154 control arm) | Mean 64 SD 10.6 | 100% | Breast | Follow-up | Intervention arm: appointments by specialist nurses according to hospital policy, at intervals consistent with hospital follow-up. Control arm: traditional hospital follow-up (consultation, clinical examination, and mammography as per hospital policy). participants were reviewed every three months for two years, six monthly for two years, then annually for a further year. | Telephone | No | Primary: Spielberger state trait anxiety inventory (STAI) | No | No |

| Beaver [51] | 2012 | Single-center | United Kingdom | 65 randomized (32 intervention arm vs. 33 control arm); 50 analysed (15 intervention arm vs. 12 control arm | Intervention arm: Mean 73.6, SD 7.6; Control arm: Mean 72.4, SD 8.2 | 42% | Colorectal | Follow-up | Intervention arm: follow-up consultations by a colorectal nurse practitioner using a structured intervention at the same prescribed intervals as the control arm. Control arm: hospital consultations at 6-weeks posttreatment, then 6-monthly intervals for 2 years and annually for a further 3 years | Telephone | No | Primary: Spielberger state trait anxiety inventory (STAI) | No | No |

| Beaver [56] | 2016 | Multicenter | United Kingdom | 259 randomized (129 intervention arm vs. 130 control arm); 117 analysed (111 intervention arm vs. 106 control arm) | Intervention arm: Median 66, IQR 60–72.5; Control arm: Median 64, IQR 57.8–69 | 100% | Endometrial | Follow-up | Intervention arm: assessment by gynaecology oncology nurse specialists at intervals consistent with hospital policy at the study locations, mirroring the frequency of scheduled hospital appointments for the control arm. Control arm: hospital based follow-up in accordance with hospital policy at the study locations. This consisted of appointments every 3 or 4 months for the first 2 years post-treatment followed by appointments at decreasing intervals (6-monthly and annually), up to a period of 3–5 years. | Telephone | No | Primary: Spielberger state trait anxiety inventory (STAI) | No | Secondary: European Organization for Research and Treatment (EORTC) QLQ-C30 (version 3) and a specific module for endometrial cancer (QLQ-EN24) |

| Kimman [52] | 2011 | Multicenter | The Netherlands | 320 randomized (162 intervention arm vs. 158 control arm); 299 analysed (150 intervention arm vs. 149 control arm) | Intervention arm: Mean 55.5, SD 9.0; Control arm: Mean 56.2, SD 10.7 | 100% | Breast | Follow-up | Intervention arm: interviews by a breast care nurse or nurse practitioner at 3, 6, 9 and 18 months, + mammography and outpatient clinic visit at 12 months. Control arm: hospital follow-up as usual: outpatient clinic visits at the same time points as for the intervention arm, including a clinical visit and a mammography at 12 months. | Telephone | No | Secondary: Spielberger state trait anxiety inventory (STAI) | No | Primary: EORTC Core Quality of Life questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) |

| Krzyzanowska [53] | 2021 | Multicenter | Canada | 2158 randomized (944 intervention arm vs. 1214 control arm); 580 participant in patient reported outcomes cohort (278 intervention arm vs. 283 control arm) | Median age 55.7 | 100% | Breast | Active treatment | Intervention arm: nurse-led assessment of common toxicities with two structured follow-up calls during each cycle of chemotherapy using a standardized questionnaire. Control arm: standard of care according to the institution. Typically, standard care involved baseline patient education on chemotherapy and common side effects, and advice to call the cancer centre about symptoms or concerns related to the treatment between visits to the clinic. | Telephone | No | Secondary: generalised anxiety disorder 7 Scale (GAD-7) | Secondary: patient health questionnaire 9 Scale (PHQ-9) | Secondary: EuroQol EQ-5 Dimensions-3 Level (EQ-5D-3L) |

| Maguire [54] | 2021 | Multicenter | Austria, Greece, Norway, Republic of Ireland, UK | 840 randomised (422 intervention arm vs. 418 control arm); 829 analysed (179 intervention arm vs. 157 control arm) | Mean 52.4, SD 12.2 | 82% | Breast, Colorectal, Hodgkin’s disease, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | Active treatment | Intervention arm: real time, 24 h monitoring and management of chemotherapy toxicity. Patients completed a toxicity self-assessment questionnaire daily and whenever they felt unwell, for up to 6 cycles of chemotherapy. Alerts to clinicians were generated when necessary. Control arm: care as usual at the cancer centre. Participants were advised to contact clinicians through standard mechanisms. | Web site | Secondary: Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) Global Distress Index (GDI) | Secondary: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory—Revised (STAI-R) | No | Secondary: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General (FACT-G) |

| Ngu [57] | 2020 | Single-center | China | 385 randomised (191 intervention arm vs. 194 in control arm); 239 anaysed (130 intervention arm vs. 136 control arm) | Intervention arm: Median 50, range 27–84; Control arm: Median 50 range 21–83 | 100% | Endometrial or ovarian cancer | Follow-up | Intervention arm: interview by research nurses at a 3-monthly interval until 2 years after treatment completion, then 6-monthly for the next 3 years and then annually, + annual clinic follow-up with gynaecologists. Control arm: follow-up according to the local routine schedule, with gynaecological clinic visits for symptom review and clinical examination, performed with the same frequency as the telephone intervention (three months for the first 2 years, then 6-monthly for next 3 years and then annually). | Telephone | No | Secondary: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | No | Secondary: European Organization for Research and Treatment (EORTC) QLQ-C30 |

| Pfeifer [55] | 2015 | Single-center | United States | 80 randomized (45 intervention arm vs. 35 control arm) | Intervention arm: Mean 60.73, SD 10.2; Control arm: Mean 59.67, SD 11.8 | 14% | Head and neck | Active treatment | Intervention arm: the participants were instructed on how to reply to algorithm questions daily, and depending on responses they would receive specific information and recommendations as to when to contact clinicians. Unrelieved symptoms or those targeted as requiring immediate intervention resulted in the coordinator contacting the patient directly by phone and/or contacting clinicians to assure effective and immediate intervention. Control arm: routine care, defined as standard-of-care/assessment-only | Telehealth messaging device connected to telephone line in the patient’s home. | Primary: Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) Global Distress Index (GDI) | No | No | Primary: The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Head & Neck Scale (FACT-HN) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caminiti, C.; Annunziata, M.A.; Di Giulio, P.; Isa, L.; Mosconi, P.; Nanni, M.G.; Piredda, M.; Verusio, C.; Diodati, F.; Maglietta, G.; et al. Psychosocial Impact of Virtual Cancer Care through Technology: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Cancers 2023, 15, 2090. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15072090

Caminiti C, Annunziata MA, Di Giulio P, Isa L, Mosconi P, Nanni MG, Piredda M, Verusio C, Diodati F, Maglietta G, et al. Psychosocial Impact of Virtual Cancer Care through Technology: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Cancers. 2023; 15(7):2090. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15072090

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaminiti, Caterina, Maria Antonietta Annunziata, Paola Di Giulio, Luciano Isa, Paola Mosconi, Maria Giulia Nanni, Michela Piredda, Claudio Verusio, Francesca Diodati, Giuseppe Maglietta, and et al. 2023. "Psychosocial Impact of Virtual Cancer Care through Technology: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials" Cancers 15, no. 7: 2090. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15072090

APA StyleCaminiti, C., Annunziata, M. A., Di Giulio, P., Isa, L., Mosconi, P., Nanni, M. G., Piredda, M., Verusio, C., Diodati, F., Maglietta, G., & Passalacqua, R. (2023). Psychosocial Impact of Virtual Cancer Care through Technology: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Cancers, 15(7), 2090. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15072090