The Role of Cytokines in the Different Stages of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

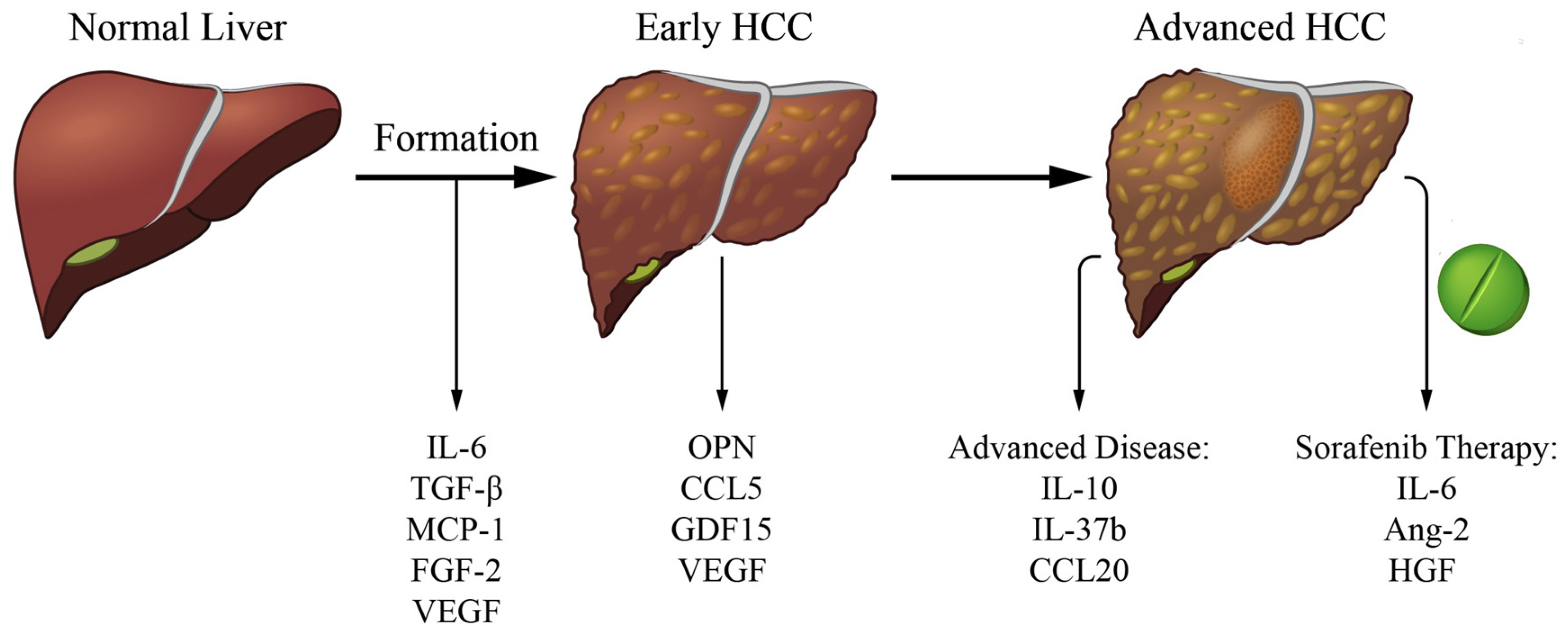

2. Cytokines Related to HCC Formation

2.1. Interleukin-6 (IL-6)

2.2. Transforming Growth Factor Beta (TGF-β)

2.3. Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein 1 (MCP-1)

2.4. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF)

2.5. Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 (FGF-2)

3. Cytokines Linked to Early Detection

3.1. Osteopontin (OPN)

3.2. CC Chemokine Ligand 5 (CCL5)

3.3. Growth Differentiation Factor 15 (GDF15)

3.4. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF)

4. Cytokines Related to Advanced HCC

4.1. Interleukin-10 (IL-10)

4.2. Interleukin-37b (IL-37b)

4.3. CC Chemokine Ligand 20 (CCL20)

5. Cytokines Related to HCC Systemic Therapy Response

5.1. Interleukin-6 (IL-6)

5.2. Angiopoietin-2 (ANG-2)

5.3. Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF)

5.4. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF)

6. Cytokines Associated with Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Burden of Disease Liver Cancer Collaboration; Akinyemiju, T.; Abera, S.; Ahmed, M.; Alam, N.; Alemayohu, M.A.; Allen, C.; Al-Raddadi, R.; Alvis-Guzman, N.; Amoako, Y.; et al. The Burden of Primary Liver Cancer and Underlying Etiologies From 1990 to 2015 at the Global, Regional, and National Level. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 1683–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Naghavi, M.; Allen, C.; Barber, R.M.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Carter, A.; Casey, D.C.; Charlson, F.J.; Chen, A.Z.; Coates, M.M.; et al. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1459–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singal, A.G.; Lampertico, P.; Nahon, P. Epidemiology and surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma: New trends. J. Hepatol. 2020, 72, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El–Serag, H.B.; Rudolph, K.L. Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Epidemiology and Molecular Carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 2557–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegen, A.; Koidl, S.; Weindel, K.; Marmé, D.; Augustin, H.G.; Fiedler, U. Expression of Angiopoietin-2 in Endothelial Cells Is Controlled by Positive and Negative Regulatory Promoter Elements. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, 1803–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Turner, M.D.; Nedjai, B.; Hurst, T.; Pennington, D.J. Cytokines and chemokines: At the crossroads of cell signalling and inflammatory disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Bioenerg. 2014, 1843, 2563–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Budhu, A.; Wang, X.W. The role of cytokines in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006, 80, 1197–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarova-Rusher, O.V.; Medina-Echeverz, J.; Duffy, A.G.; Greten, T.F. The yin and yang of evasion and immune activation in HCC. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 1420–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zeng, S.; Shen, H. From bench to bed: The tumor immune microenvironment and current immunotherapeutic strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cabillic, F.; Corlu, A. Regulation of Transdifferentiation and Retrodifferentiation by Inflammatory Cytokines in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marisi, G.; Cucchetti, A.; Ulivi, P.; Canale, M.; Cabibbo, G.; Solaini, L.; Foschi, F.G.; De Matteis, S.; Ercolani, G.; Valgiusti, M.; et al. Ten years of sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma: Are there any predictive and/or prognostic markers? World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 4152–4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, S.; Kelly, D.; O’Kane, G.M. Non-Immunotherapy Options for the First-Line Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Exploring the Evolving Role of Sorafenib and Lenvatinib in Advanced Disease. Curr. Oncol. 2020, 27, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Dai, Z.; Zhou, J. Biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma: Progression in early diagnosis, prognosis, and personalized therapy. Biomark. Res. 2013, 1, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Parikh, N.D.; Mehta, A.S.; Singal, A.G.; Block, T.; Marrero, J.A.; Lok, A.S. Biomarkers for the Early Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2020, 29, 2495–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rose-John, S.; Winthrop, K.; Calabrese, L. The role of IL-6 in host defence against infections: Immunobiology and clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2017, 13, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taub, R. Liver regeneration: From myth to mechanism. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 5, 836–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, N.; Dwarakanath, B.S.; Das, A.; Bhatt, A.N. Role of interleukin-6 in cancer progression and therapeutic resistance. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 11553–11572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.-X.; Ling, Y.; Wang, H.-Y. Role of nonresolving inflammation in hepatocellular carcinoma development and progression. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2018, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shakiba, E.; Ramezani, M.; Sadeghi, M. Evaluation of serum interleukin-6 levels in hepatocellular carcinoma patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2018, 4, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, J.-T.; Lai, H.-C.; Tsai, S.-M.; Lin, P.-C.; Chuang, P.-H.; Yu, C.-J.; Cheng, K.-S.; Su, W.-P.; Hsu, P.-N.; Peng, C.-Y.; et al. Rather than interleukin-27, interleukin-6 expresses positive correlation with liver severity in naïve hepatitis B infection patients. Liver Int. 2012, 32, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, J.-T.; Feng, C.-L.; Yu, C.-J.; Tsai, S.-M.; Hsu, P.-N.; Chen, Y.-L.; Wu, Y.-Y. IL-6, through p-STAT3 rather than p-STAT1, activates hepatocarcinogenesis and affects survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients: A cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lai, S.-C.; Su, Y.-T.; Chi, C.-C.; Kuo, Y.-C.; Lee, K.-F.; Wu, Y.-C.; Lan, P.-C.; Yang, M.-H.; Chang, T.-S.; Huang, Y.-H. DNMT3b/OCT4 expression confers sorafenib resistance and poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma through IL-6/STAT3 regulation. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hatting, M.; Spannbauer, M.; Peng, J.; Al Masaoudi, M.; Sellge, G.; Nevzorova, Y.A.; Gassler, N.; Liedtke, C.; Cubero, F.J.; Trautwein, C. Lack of gp130 expression in hepatocytes attenuates tumor progression in the DEN model. Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yu, L.-X.; Yan, H.-X.; Liu, Q.; Yang, W.; Wu, H.-P.; Dong, W.; Tang, L.; Lin, Y.; He, Y.-Q.; Zou, S.-S.; et al. Endotoxin accumulation prevents carcinogen-induced apoptosis and promotes liver tumorigenesis in rodents. Hepatology 2010, 52, 1322–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albillos, A.; de la Hera, A.; González, M.; Moya, J.; Calleja, J.; Monserrat, J.; Ruiz-Del-Arbol, L.; Alvarez-Mon, M. Increased lipopolysaccharide binding protein in cirrhotic patients with marked immune and hemodynamic derangement. Hepatology 2003, 37, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naugler, W.E.; Sakurai, T.; Kim, S.; Maeda, S.; Kim, K.; Elsharkawy, A.M.; Karin, M. Gender Disparity in Liver Cancer Due to Sex Differences in MyD88-Dependent IL-6 Production. Science 2007, 317, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lanton, T.; Shriki, A.; Nechemia-Arbely, Y.; Abramovitch, R.; Levkovitch, O.; Adar, R.; Rosenberg, N.; Paldor, M.; Goldenberg, D.; Sonnenblick, A.; et al. Interleukin 6-dependent genomic instability heralds accelerated carcinogenesis following liver regeneration on a background of chronic hepatitis. Hepatology 2017, 65, 1600–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Yan, Z.; Yang, H.; Sun, W.; Yao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, R. IL-6 promotes PD-L1 expression in monocytes and macrophages by decreasing protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type O expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Dhar, D.; Nakagawa, H.; Font-Burgada, J.; Ogata, H.; Jiang, Y.; Shalapour, S.; Seki, E.; Yost, S.; Jepsen, K.; et al. Identification of Liver Cancer Progenitors Whose Malignant Progression Depends on Autocrine IL-6 Signaling. Cell 2013, 155, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Massague, J. TGFβ in Cancer. Cell 2008, 134, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Furuta, K.; Misao, S.; Takahashi, K.; Tagaya, T.; Fukuzawa, Y.; Ishikawa, T.; Yoshioka, K.; Kakumu, S. Gene mutation of transforming growth factor beta1 type II receptor in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 1999, 81, 851–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, L.; Hill, C.S. Alterations in components of the TGF-β superfamily signaling pathways in human cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006, 17, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakicier, M.C.; Irmak, M.B.; Romano, A.; Kew, M.; Ozturk, M. Smad2 and Smad4 gene mutations in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene 1999, 18, 4879–4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gomis, R.; Alarcón, C.; Nadal, C.; Van Poznak, C.; Massagué, J. C/EBPβ at the core of the TGFβ cytostatic response and its evasion in metastatic breast cancer cells. Cancer Cell 2006, 10, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seoane, J.; Le, H.-V.; Shen, L.; Anderson, S.A.; Massague, J. Integration of Smad and Forkhead Pathways in the Control of Neuroepithelial and Glioblastoma Cell Proliferation. Cell 2004, 117, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roncalli, M.; Bianchi, P.; Bruni, B.; Laghi, L.; Destro, A.; Di Gioia, S.; Gennari, L.; Tommasini, M.; Malesci, A.; Coggi, G. Methylation framework of cell cycle gene inhibitors in cirrhosis and associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2002, 36, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Liu, J.-Y.; Li, B.; Sun, Z.-L.; Sun, Z.-F. Association of low p16INK4a and p15INK4b mRNAs expression with their CpG islands methylation with human hepatocellular carcinogenesis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 10, 1276–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukai, K.; Yokosuka, O.; Imazeki, F.; Tada, M.; Mikata, R.; Miyazaki, M.; Ochiai, T.; Saisho, H. Methylation status of p14ARF, p15INK4b, and p16INK4a genes in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2005, 25, 1209–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tai, G. Role of C-Jun N-terminal Kinase in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Development. Target. Oncol. 2016, 11, 723–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Murata, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Zaki, K.M. TGF-β/Smad signaling during hepatic fibro-carcinogenesis (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 45, 1363–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yamashita, M.; Fatyol, K.; Jin, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.E. TRAF6 Mediates Smad-Independent Activation of JNK and p38 by TGF-β. Mol. Cell 2008, 31, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nagata, H.; Hatano, E.; Tada, M.; Murata, M.; Kitamura, K.; Asechi, H.; Narita, M.; Yanagida, A.; Tamaki, N.; Yagi, S.; et al. Inhibition of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase switches Smad3 signaling from oncogenesis to tumor- suppression in rat hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2009, 49, 1944–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, M.; Matsuzaki, K.; Yoshida, K.; Sekimoto, G.; Tahashi, Y.; Mori, S.; Uemura, Y.; Sakaida, N.; Fujisawa, J.; Seki, T.; et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein shifts human hepatic transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling from tumor suppression to oncogenesis in early chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 2008, 49, 1203–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, K.; Murata, M.; Yoshida, K.; Sekimoto, G.; Uemura, Y.; Sakaida, N.; Kaibori, M.; Kamiyama, Y.; Nishizawa, M.; Fujisawa, J.; et al. Chronic inflammation associated with hepatitis C virus infection perturbs hepatic transforming growth factor β signaling, promoting cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2007, 46, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Ding, J.; Chen, C.; Sun, W.; Ning, B.-F.; Wen, W.; Huang, L.; Han, T.; Yang, W.; Wang, C.; et al. Hepatic transforming growth factor beta gives rise to tumor-initiating cells and promotes liver cancer development. Hepatology 2012, 56, 2255–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagyaraj, E.; Ahuja, N.; Kumar, S.; Tiwari, D.; Gupta, S.; Nanduri, R.; Gupta, P. TGF-β induced chemoresistance in liver cancer is modulated by xenobiotic nuclear receptor PXR. Cell Cycle 2019, 18, 3589–3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlmark, K.R.; Weiskirchen, R.; Zimmermann, H.W.; Gassler, N.; Ginhoux, F.; Weber, C.; Merad, M.; Luedde, T.; Trautwein, C.; Tacke, F. Hepatic recruitment of the inflammatory Gr1+monocyte subset upon liver injury promotes hepatic fibrosis. Hepatology 2009, 50, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapanadze, T.; Gamrekelashvili, J.; Ma, C.; Chan, C.; Zhao, F.; Hewitt, S.; Zender, L.; Kapoor, V.; Felsher, D.W.; Manns, M.P.; et al. Regulation of accumulation and function of myeloid derived suppressor cells in different murine models of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2013, 59, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baeck, C.; Wehr, A.; Karlmark, K.R.; Heymann, F.; Vucur, M.; Gassler, N.; Huss, S.; Klussmann, S.; Eulberg, D.; Luedde, T.; et al. Pharmacological inhibition of the chemokine CCL2 (MCP-1) diminishes liver macrophage infiltration and steatohepatitis in chronic hepatic injury. Gut 2011, 61, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacke, F. Targeting hepatic macrophages to treat liver diseases. J. Hepatol. 2017, 66, 1300–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, J.W. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yao, W.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, P.; Li, B.; Li, J.; Chu, R.; Song, H.; Xie, D.; Jiang, X.; et al. Targeting of tumour-infiltrating macrophages via CCL2/CCR2 signalling as a therapeutic strategy against hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut 2015, 66, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, Y.-T.; Wang, M.-C.; Zhou, J.; Peng, H.-H.; Lee, D.-Y.; Chiu, J.-J. Endothelial progenitors promote hepatocarcinoma intrahepatic metastasis through monocyte chemotactic protein-1 induction of microRNA-21. Gut 2014, 64, 1132–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D.; Folkman, J. Patterns and Emerging Mechanisms of the Angiogenic Switch during Tumorigenesis. Cell 1996, 86, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoeben, A.; Landuyt, B.; Highley, M.S.; Wildiers, H.; Van Oosterom, A.T.; De Bruijn, E.A. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Angiogenesis. Pharmacol. Rev. 2004, 56, 549–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.; Semela, D.; Bruix, J.; Colle, I.; Pinzani, M.; Bosch, J. Angiogenesis in liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2009, 50, 604–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.N.; Kim, Y.-B.; Yang, K.M.; Park, C. Increased Expression of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Angiogenesis in the Early Stage of Multistep Hepatocarcinogenesis. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2000, 124, 1061–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, M.; Nishikawa, T.; Nakajima, T.; Okada, Y.; Yamaguchi, K.; Mitsuyoshi, H.; Yasui, K.; Minami, M.; Iwai, M.; Kagawa, K.; et al. Oxidative stress is closely associated with tumor angiogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 46, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satake, S.; Kuzuya, M.; Miura, H.; Asai, T.; Ramos, M.A.; Muraguchi, M.; Ohmoto, Y.; Iguchi, A. Up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor in response to glucose deprivation. Biol. Cell 1998, 90, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuzuki, Y.; Fukumura, D.; Oosthuyse, B.; Koike, C.; Carmeliet, P.; Jain, R.K. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) modulation by targeting hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha → hypoxia response element → VEGF cascade differentially regulates vascular response and growth rate in tumors. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 6248–6252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vizio, B.; Bosco, O.; David, E.; Caviglia, G.P.; Abate, M.L.; Schiavello, M.; Pucci, A.; Smedile, A.; Paraluppi, G.; Romagnoli, R.; et al. Cooperative Role of Thrombopoietin and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-A in the Progression of Liver Cirrhosis to Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocca, C.; Novo, E.; Miglietta, A.; Parola, M. Angiogenesis and Fibrogenesis in Chronic Liver Diseases. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 1, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Burgess, W.H.; Maciag, T. The Heparin-Binding (Fibroblast) Growth Factor Family of Proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1989, 58, 575–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asada, N.; Tanaka, Y.; Hayashido, Y.; Toratani, S.; Kan, M.; Kitamoto, M.; Nakanishi, T.; Kajiyama, G.; Chayama, K.; Okamoto, T. Expression of fibroblast growth factor receptor genes in human hepatoma-derived cell lines. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2003, 39, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Park, H.; Chhim, S.; Ding, Y.; Jiang, W.; Queen, C.; Kim, K.J. A Novel Monoclonal Antibody to Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 Effectively Inhibits Growth of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Xenografts. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2012, 11, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wyder, L.; Vitaliti, A.; Schneider, H.; Hebbard, L.W.; Moritz, D.R.; Wittmer, M.; Ajmo, M.; Klemenz, R. Increased expression of H/T-cadherin in tumor-penetrating blood vessels. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 4682–4688. [Google Scholar]

- Adachi, Y.; Takeuchi, T.; Sonobe, H.; Ohtsuki, Y. An adiponectin receptor, T-cadherin, was selectively expressed in intratumoral capillary endothelial cells in hepatocellular carcinoma: Possible cross talk between T-cadherin and FGF-2 pathways. Virchows Archiv 2005, 448, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim-No, K.; Tanimizu, M.; Hyodo, I.; Kurimoto, F.; Yamashita, T. Plasma level of basic fibroblast growth factor increases with progression of chronic liver disease. J. Gastroenterol. 1997, 32, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, R.T.-P.; Ng, I.O.-L.; Lau, C.; Yu, W.-C.; Fan, S.-T.; Wong, J. Correlation of serum basic fibroblast growth factor levels with clinicopathologic features and postoperative recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. 2001, 182, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzartzeva, K.; Obi, J.; Rich, N.E.; Parikh, N.D.; Marrero, J.A.; Yopp, A.; Waljee, A.K.; Singal, A.G. Surveillance Imaging and Alpha Fetoprotein for Early Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With Cirrhosis: A Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 1706–1718.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, L.F.; Berse, B.; Van De Water, L.; Papadopoulos-Sergiou, A.; Perruzzi, C.A.; Manseau, E.J.; Dvorak, H.F.; Senger, D.R. Expression and distribution of osteopontin in human tissues: Widespread association with luminal epithelial surfaces. Mol. Biol. Cell 1992, 3, 1169–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liaw, L.; Birk, D.E.; Ballas, C.B.; Whitsitt, J.S.; Davidson, J.M.; Hogan, B.L. Altered wound healing in mice lacking a functional osteopontin gene (spp1). J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 101, 1468–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Brien, E.R.; Garvin, M.R.; Stewart, D.K.; Hinohara, T.; Simpson, J.B.; Schwartz, S.M.; Giachelli, C.M. Osteopontin is synthesized by macrophage, smooth muscle, and endothelial cells in primary and restenotic human coronary atherosclerotic plaques. Arter. Thromb. A J. Vasc. Biol. 1994, 14, 1648–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhao, H.; Chen, Q.; Alam, A.; Cui, J.; Suen, K.C.; Soo, A.P.; Eguchi, S.; Gu, J.; Ma, D. The role of osteopontin in the progression of solid organ tumour. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.; Plymoth, A.; Ge, S.; Feng, Z.; Rosen, H.R.; Sangrajrang, S.; Hainaut, P.; Marrero, J.A.; Beretta, L. Identification of osteopontin as a novel marker for early hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2011, 55, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, L.; Rong, W.; Xiao, T.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Wu, F.; Qi, J.; Zhao, X.; et al. Secretory/releasing proteome-based identification of plasma biomarkers in HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. China Life Sci. 2013, 56, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ge, T.; Shen, Q.; Wang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, Z.; Chu, W.; Lv, X.; Zhao, F.; Zhao, W.; Fan, J.; et al. Diagnostic values of alpha-fetoprotein, dickkopf-1, and osteopontin for hepatocellular carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2015, 32, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vongsuvanh, R.; Van Der Poorten, D.; Iseli, T.; Strasser, S.I.; Mccaughan, G.; George, J. Midkine Increases Diagnostic Yield in AFP Negative and NASH-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Zheng, J.; Wu, F.; Kang, B.; Liang, J.; Heskia, F.; Zhang, X.; Shan, Y. OPN is a promising serological biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 3596–3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimparlee, N.; Chuaypen, N.; Khlaiphuengsin, A.; Pinjaroen, N.; Payungporn, S.; Poovorawan, Y.; Tangkijvanich, P. Diagnostic and Prognostic Roles of Serum Osteopontin and Osteopontin Promoter Polymorphisms in Hepatitis B-related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 16, 7211–7217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, A.N.; Plymoth, A.; Santos-Silva, D.; Ortiz-Cuaran, S.; Camey, S.; Guilloreau, P.; Sangrajrang, S.; Khuhaprema, T.; Mendy, M.; Lesi, O.A.; et al. Osteopontin and latent-TGF β binding-protein 2 as potential diagnostic markers for HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 136, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duarte-Salles, T.; Misra, S.; Stepien, M.; Plymoth, A.; Muller, D.; Overvad, K.; Olsen, A.; Tjonneland, A.; Baglietto, L.; Severi, G.; et al. Circulating Osteopontin and Prediction of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Development in a Large European Population. Cancer Prev. Res. 2016, 9, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crawford, A.; Angelosanto, J.M.; Nadwodny, K.L.; Blackburn, S.D.; Wherry, E.J. A Role for the Chemokine RANTES in Regulating CD8 T Cell Responses during Chronic Viral Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrubia, S.B.-M.J.R.; Benito-Martínez, S.; Calvino, M.; Sanz-De-Villalobos, E.; Parra-Cid, T. Role of chemokines and their receptors in viral persistence and liver damage during chronic hepatitis C virus infection. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 7149–7159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, C.; Wang, F.; Kong, X. Functional roles of CCL5/RANTES in liver disease. Liver Res. 2020, 4, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.R.; Lahdou, I.; Oweira, H.; Daniel, V.; Terness, P.; Schmidt, J.M.; Weiss, K.-H.; Longerich, T.; Schemmer, P.; Opelz, G.; et al. Serum levels of chemokines CCL4 and CCL5 in cirrhotic patients indicate the presence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 113, 756–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wischhusen, J.; Melero, I.; Fridman, W.H. Growth/Differentiation Factor-15 (GDF-15): From Biomarker to Novel Targetable Immune Checkpoint. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chi, X.; Gong, Q.; Gao, L.; Niu, Y.; Chi, X.; Cheng, M.; Si, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhong, J.; et al. Association of Serum Level of Growth Differentiation Factor 15 with Liver Cirrhosis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaseb, A.O.; Hanbali, A.; Cotant, M.; Hassan, M.M.; Wollner, I.; Philip, P.A. Vascular endothelial growth factor in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 2009, 115, 4895–4906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukozu, T.; Nagai, H.; Matsui, D.; Kanekawa, T.; Sumino, Y. Serum VEGF as a tumor marker in patients with HCV-related liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Anticancer Res 2013, 33, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, S.S.; Zekri, A.-R.; Bahnassy, A.A.; Alam El-Din, H.M.; Morsy, H.M.; Shaarawy, S.; Moharram, N.Z. Serum levels of β-catenin as a potential marker for genotype 4/hepatitis C-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2011, 26, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debes, J.D.; van Tilborg, M.; Groothuismink, Z.M.; Hansen, B.E.; Wiesch, J.S.Z.; von Felden, J.; de Knegt, R.J.; Boonstra, A. Levels of Cytokines in Serum Associate With Development of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With HCV Infection Treated With Direct-Acting Antivirals. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 515–517.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrero, J.A.; Fontana, R.J.; Barrat, A.; Askari, F.K.; Conjeevaram, H.S.; Su, G.; Lok, A.S.-F. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: Comparison of 7 staging systems in an American cohort. Hepatology 2005, 41, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer EASL–EORTC Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2012, 56, 908–943. [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marrero, J.A.; Kulik, L.M.; Sirlin, C.B.; Zhu, A.X.; Finn, R.S.; Abecassis, M.M.; Roberts, L.R.; Heimbach, J.K. Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018, 68, 723–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iyer, S.S.; Cheng, G. Role of Interleukin 10 Transcriptional Regulation in Inflammation and Autoimmune Disease. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 32, 23–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ouyang, W.; O’Garra, A. IL-10 Family Cytokines IL-10 and IL-22: From Basic Science to Clinical Translation. Immunity 2019, 50, 871–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, K.W.; Malefyt, R.D.W.; Coffman, R.L.; O’Garra, A. INTERLEUKIN-10AND THEINTERLEUKIN-10 RECEPTOR. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2001, 19, 683–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chau, G.-Y.; Wu, C.-W.; Lui, W.-Y.; Chang, T.-J.; Kao, H.-L.; Wu, L.-H.; King, K.-L.; Loong, C.-C.; Hsia, C.-Y.; Chi, C.-W. Serum Interleukin-10 But Not Interleukin-6 Is Related to Clinical Outcome in Patients With Resectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Ann. Surg. 2000, 231, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, E. Possible contribution of circulating interleukin-10 (IL-10) to anti-tumor immunity and prognosis in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol. Res. 2003, 27, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, S.L.; Mo, F.K.F.; Wong, C.S.C.; Chan, C.M.L.; Leung, L.K.S.; Hui, E.P.; Ma, B.B.; Chan, A.T.C.; Mok, T.S.K.; Yeo, W. A study of circulating interleukin 10 in prognostication of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 2011, 118, 3984–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Li, Y.; Guo, C.; Wang, L.; Chu, H.; Zhu, F.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, W.; et al. IL-37 isoform D downregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines expression in a Smad3-dependent manner. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, K.J.; Houston, A.; Brint, E. IL-1 Family Members in Cancer; Two Sides to Every Story. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, T.-T.; Zhu, D.; Mou, T.; Guo, Z.; Pu, J.-L.; Chen, Q.-S.; Wei, X.-F.; Wu, Z.-J. IL-37 induces autophagy in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Mol. Immunol. 2017, 87, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, X.-Y.; Zheng, D.-F.; Shen, A.; Gu, H.-T.; Wei, X.-F.; Mou, T.; Zhang, J.-B.; Liu, R. IL-37b suppresses epithelial mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting IL-6/STAT3 signaling. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2018, 17, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Tang, C.; Shen, A.; Luo, H.; Wei, X.; Zheng, D.; Sun, C.; Li, Z.; Zhu, D.; Li, T.; et al. IL-37 suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma growth by converting pSmad3 signaling from JNK/pSmad3L/c-Myc oncogenic signaling to pSmad3C/P21 tumor-suppressive signaling. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 85079–85096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Luo, C.; Shu, Y.; Luo, J.; Liu, D.; Huang, D.-S.; Han, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, Y.-C.; Zou, J.-M.; Qin, J.; et al. Intracellular IL-37b interacts with Smad3 to suppress multiple signaling pathways and the metastatic phenotype of tumor cells. Oncogene 2017, 36, 2889–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadomoto, S.; Izumi, K.; Mizokami, A. The CCL20-CCR6 Axis in Cancer Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutyser, E.; Struyf, S.; Van Damme, J. The CC chemokine CCL20 and its receptor CCR6. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003, 14, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Li, H.; Liu, H.; Ma, X.; Yang, S.; Wang, Z. DEPDC1 drives hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation, invasion and angiogenesis by regulating the CCL20/CCR6 signaling pathway. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 42, 1075–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rubie, C.; Frick, V.O.; Wagner, M.; Rau, B.; Weber, C.; Kruse, B.; Kempf, K.; Tilton, B.; Konig, J.; Schilling, M. Enhanced Expression and Clinical Significance of CC-Chemokine MIP-3alpha in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Scand. J. Immunol. 2006, 63, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubie, C.; Frick, V.O.; Wagner, M.; Weber, C.; Kruse, B.; Kempf, K.; König, J.; Rau, B.; Schilling, M. Chemokine expression in hepatocellular carcinoma versus colorectal liver metastases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 12, 6627–6633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-J.; Lin, S.-Z.; Zhou, L.; Xie, H.-Y.; Zhou, W.-H.; Taki-Eldin, A.; Zheng, S.-S. Selective Recruitment of Regulatory T Cell through CCR6-CCL20 in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Fosters Tumor Progression and Predicts Poor Prognosis. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llovet, J.M.; Zucman-Rossi, J.; Pikarsky, E.; Sangro, B.; Schwartz, M.; Sherman, M.; Gores, G. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2016, 2, 16018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Ikeda, M.; Galle, P.R.; Ducreux, M.; Kim, T.-Y.; Kudo, M.; Breder, V.; Merle, P.; Kaseb, A.O.; et al. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1894–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, C.; Klempner, S.; Ali, S.M.; Madison, R.; Ross, J.S.; Severson, E.A.; Fabrizio, D.; Goodman, A.; Kurzrock, R.; Suh, J.; et al. Prevalence of established and emerging biomarkers of immune checkpoint inhibitor response in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 4018–4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rizzo, A. The evolving landscape of systemic treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and biliary tract cancer. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2021, 27, 100360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teufel, M.; Seidel, H.; Köchert, K.; Meinhardt, G.; Finn, R.S.; Llovet, J.M.; Bruix, J. Biomarkers Associated With Response to Regorafenib in Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1731–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ono, A.; Aikata, H.; Yamauchi, M.; Kodama, K.; Ohishi, W.; Kishi, T.; Ohya, K.; Teraoka, Y.; Osawa, M.; Fujino, H.; et al. Circulating cytokines and angiogenic factors based signature associated with the relative dose intensity during treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma receiving lenvatinib. Ther. Adv. Med Oncol. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.-Y.; Lin, H.; Li, Y.-S.; Lee, Y.-H.; Chen, H.-M.; Cheng, A.-L.; Hsu, C.-H. High plasma interleukin-6 levels associated with poor prognosis of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 47, 949–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llovet, J.M.; Peña, C.E.; Lathia, C.D.; Shan, M.; Meinhardt, G.; Bruix, J. Plasma Biomarkers as Predictors of Outcome in Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 2290–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miyahara, K.; Nouso, K.; Morimoto, Y.; Takeuchi, Y.; Hagihara, H.; Kuwaki, K.; Onishi, H.; Ikeda, F.; Miyake, Y.; Nakamura, S.; et al. Pro-angiogenic cytokines for prediction of outcomes in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 2072–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, T.-H.; Shao, Y.-Y.; Chan, S.-Y.; Huang, C.-Y.; Hsu, C.-H.; Cheng, A.-L. High Serum Transforming Growth Factor-β1 Levels Predict Outcome in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients Treated with Sorafenib. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 3678–3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adachi, T.; Nouso, K.; Miyahara, K.; Oyama, A.; Wada, N.; Dohi, C.; Takeuchi, Y.; Yasunaka, T.; Onishi, H.; Ikeda, F.; et al. Monitoring serum proangiogenic cytokines from hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with sorafenib. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 34, 1081–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.; Chen, G.; Han, Z.; Cheng, H.; Qiao, L.; Li, Y. IL-6/STAT3 Signaling Contributes to Sorafenib Resistance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Through Targeting Cancer Stem Cells. OncoTargets Ther. 2020, ume 13, 9721–9730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, H.G.; Koh, G.Y.; Thurston, G.; Alitalo, K. Control of vascular morphogenesis and homeostasis through the angiopoietin–Tie system. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiedler, U.; Reiss, Y.; Scharpfenecker, M.; Grunow, V.; Koidl, S.; Thurston, G.; Gale, N.W.; Witzenrath, M.; Rosseau, S.; Suttorp, N.; et al. Angiopoietin-2 sensitizes endothelial cells to TNF-α and has a crucial role in the induction of inflammation. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, N.W.; Thurston, G.; Hackett, S.F.; Renard, R.; Wang, Q.; McClain, J.; Martin, C.; Witte, C.; Witte, M.H.; Jackson, D.; et al. Angiopoietin-2 Is Required for Postnatal Angiogenesis and Lymphatic Patterning, and Only the Latter Role Is Rescued by Angiopoietin-1. Dev. Cell 2002, 3, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, S.; Columbano, A. Met as a therapeutic target in HCC: Facts and hopes. J. Hepatol. 2014, 60, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuchiya, K.; Asahina, Y.; Matsuda, S.; Muraoka, M.; Nakata, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Tamaki, N.; Yasui, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Hosokawa, T.; et al. Changes in plasma vascular endothelial growth factor at 8 weeks after sorafenib administration as predictors of survival for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 2013, 120, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hui, E. Immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Cell Biol. 2019, 218, 740–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, T.K.; Herbst, R.S.; Chen, L. Defining and Understanding Adaptive Resistance in Cancer Immunotherapy. Trends Immunol. 2018, 39, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taube, J.M.; Klein, A.; Brahmer, J.R.; Xu, H.; Pan, X.; Kim, J.H.; Chen, L.; Pardoll, D.M.; Topalian, S.L.; Anders, R.A. Association of PD-1, PD-1 Ligands, and Other Features of the Tumor Immune Microenvironment with Response to Anti–PD-1 Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 5064–5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Munker, S.; De Toni, E.N. Use of checkpoint inhibitors in liver transplant recipients. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2018, 6, 970–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, Y.; Yang, J.; Xu, D.; Gao, X.-M.; Zhang, Z.; Hsu, J.L.; Li, C.-W.; Lim, S.-O.; Sheng, Y.-Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Disruption of tumour-associated macrophage trafficking by the osteopontin-induced colony-stimulating factor-1 signalling sensitises hepatocellular carcinoma to anti-PD-L1 blockade. Gut 2019, 68, 1653–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, R.; Prithviraj, P.; Anaka, M.; Bridle, K.R.; Crawford, D.H.G.; Dhungel, B.; Steel, J.; Jayachandran, A. Monitoring Immune Checkpoint Regulators as Predictive Biomarkers in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Chen, H.; Yang, K.; Zhang, G.; Mao, B.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J. Peripheral cytokine levels as predictive biomarkers of benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer therapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 129, 110457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feun, L.G.; Li, Y.; Wu, C.; Wangpaichitr, M.; Jones, P.D.; Richman, S.P.; Madrazo, B.; Kwon, D.; Garcia-Buitrago, M.; Martin, P.; et al. Phase 2 study of pembrolizumab and circulating biomarkers to predict anticancer response in advanced, unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 2019, 125, 3603–3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| THERAPY | N PATIENTS | TYPE OF STUDY | EVALUATED CYTOKINE/S—BIOMARKERS | OUTCOMES | REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SORAFENIB | 128 | Retrospective | IL-6 | OS, PFS and TTP | Shao et al., 2017 [121] |

| SORAFENIB | 299 | Randomized–controlled | ANG-2, EGF, bFGF, VEGF, sVEGFR-2, sVEGFR-3, HGF, and s-c-KIT, IGF-2 | OS, TTP | Llovet et al., 2012 [122] |

| SORAFENIB | 120 | Retrospective | ANG-2, FST, G-CSF, HGF, Leptin, PDGF-BB, PECAM-1, and VEGF | OS, PFS | Miyahara et al., 2013 [123] |

| SORAFENIB | 91 | Retrospective | TGF-β | OS, PFS | Lin et al., 2015 [124] |

| SORAFENIB | 80 | Prospective | FST, G-CSF, HGF, Leptin, PDGF-BB, PECAM-1, ANG-2, VEGF | OS, PFS | T. Adachi et al., 2019 [125] |

| LENVATINIB | 41 | Retrospective | aFGF, bFGF, FGF-23, VEGF-R3, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, EGF, Fas, FasL, IL-1R2, PDGF-BB, TSP-2, Ang-1, ANG-2, Tie-2, CXCL8, HGF, Neuropilin-1, c-MET, HGF, IFN-β | OS, PFS, PD | Ono et al., 2020 [120] |

| REGORAFENIB | 332 | Randomized–controlled | 294 biomarkers (DiscoveryMAP) | OS, TTP | Teufel et al., 2019 [119] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rico Montanari, N.; Anugwom, C.M.; Boonstra, A.; Debes, J.D. The Role of Cytokines in the Different Stages of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 4876. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13194876

Rico Montanari N, Anugwom CM, Boonstra A, Debes JD. The Role of Cytokines in the Different Stages of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers. 2021; 13(19):4876. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13194876

Chicago/Turabian StyleRico Montanari, Noe, Chimaobi M. Anugwom, Andre Boonstra, and Jose D. Debes. 2021. "The Role of Cytokines in the Different Stages of Hepatocellular Carcinoma" Cancers 13, no. 19: 4876. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13194876

APA StyleRico Montanari, N., Anugwom, C. M., Boonstra, A., & Debes, J. D. (2021). The Role of Cytokines in the Different Stages of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers, 13(19), 4876. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13194876