Risk-Reducing Mastectomy and Reconstruction Following Prophylactic Breast Irradiation: Hope Sustained

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Levy-Lahad, E.; Friedman, E. Cancer risks among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Br. J. Cancer 2007, 96, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, E.; Foulkes, W.; Goodwin, P.; Meschino, W.; Blondal, J.; Paterson, C.; Ozcelik, H.; Goss, P.; Allingham-Hawkins, D.; Hamel, N.; et al. Prevalence and penetrance of BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations in unselected Ashkenazi Jewish women with breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1999, 91, 1241–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhani, S.R.; Jacquemier, J.; Sloane, J.P.; Gusterson, B.A.; Anderson, T.J.; van de Vijver, M.J.; Farid, L.M.; Venter, D.; Antoniou, A.; Storfer-Isser, A.; et al. Multifactorial analysis of differences between sporadic breast cancers and cancers involving BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1998, 90, 1138–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuchenbaecker, K.B.; Hopper, J.L.; Barnes, D.R.; Phillips, K.A.; Mooij, T.M.; Roos-Blom, M.J.; Jervis, S.; van Leeuwen, F.E.; Milne, R.L.; Andrieu, N.; et al. Risks of Breast, Ovarian, and Contralateral Breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. JAMA 2017, 317, 2402–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evron, E.; Ben-David, A.M.; Goldberg, H.; Fried, G.; Kaufman, B.; Catane, R.; Pfeffer, M.R.; Geffen, D.B.; Chernobelsky, P.; Karni, T.; et al. Prophylactic irradiation to the contralateral breast for BRCA mutation carriers with early-stage breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2019, 30, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortmans, P.M.P.; Kaidar-Person, O. Contralateral breast irradiation in BRCA carriers: The conundrum of prophylactic versus early treatment. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2019, 30, 348–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narod, S.A. Is bilateral radiation an option for BRCA mutation carriers with unilateral breast cancer? Ann. Transl. Med. 2019, 7, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, A.Y.; Hu, Z.I.; Mehrara, B.J.; Wilkins, E.G. Radiotherapy in the setting of breast reconstruction: Types, techniques, and timing. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, e742–e753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaidar-Person, O.; Offersen, B.V.; Boersma, L.J.; de Ruysscher, D.; Tramm, T.; Kühn, T.; Gentilini, O.; Mátrai, Z.; Poortmans, P. A multidisciplinary view of mastectomy and breast reconstruction: Understanding the challenges. Breast (Edinb. Scotl.) 2021, 56, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, S.L.; Baker, J.L., Jr. Classification of capsular contracture after prosthetic breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr. Surg. 1995, 96, 1119–1123, discussion 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebbeck, T.R.; Friebel, T.; Lynch, H.T.; Neuhausen, S.L.; van ‘t Veer, L.; Garber, J.E.; Evans, G.R.; Narod, S.A.; Isaacs, C.; Matloff, E.; et al. Bilateral prophylactic mastectomy reduces breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: The PROSE Study Group. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, L.C.; Sellers, T.A.; Schaid, D.J.; Frank, T.S.; Soderberg, C.L.; Sitta, D.L.; Frost, M.H.; Grant, C.S.; Donohue, J.H.; Woods, J.E.; et al. Efficacy of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutation carriers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2001, 93, 1633–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers-Heijboer, H.; van Geel, B.; van Putten, W.L.; Henzen-Logmans, S.C.; Seynaeve, C.; Menke-Pluymers, M.B.; Bartels, C.C.; Verhoog, L.C.; van den Ouweland, A.M.; Niermeijer, M.F.; et al. Breast cancer after prophylactic bilateral mastectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brose, M.S.; Rebbeck, T.R.; Calzone, K.A.; Stopfer, J.E.; Nathanson, K.L.; Weber, B.L. Cancer risk estimates for BRCA1 mutation carriers identified in a risk evaluation program. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2002, 94, 1365–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, L.J.; Haffty, B.G. Radiotherapy in the treatment of hereditary breast cancer. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2011, 21, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heemskerk-Gerritsen, B.A.M.; Jager, A.; Koppert, L.B.; Obdeijn, A.I.; Collée, M.; Meijers-Heijboer, H.E.J.; Jenner, D.J.; Oldenburg, H.S.A.; van Engelen, K.; de Vries, J.; et al. Survival after bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy in healthy BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 177, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tung, N.M.; Boughey, J.C.; Pierce, L.J.; Robson, M.E.; Bedrosian, I.; Dietz, J.R.; Dragun, A.; Gelpi, J.B.; Hofstatter, E.W.; Isaacs, C.J.; et al. Management of Hereditary Breast Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society for Radiation Oncology, and Society of Surgical Oncology Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 2080–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, K.; Eisen, A.; Senter, L.; Armel, S.; Bordeleau, L.; Meschino, W.S.; Pal, T.; Lynch, H.T.; Tung, N.M.; Kwong, A.; et al. International trends in the uptake of cancer risk reduction strategies in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 121, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, L.J.; Levin, A.M.; Rebbeck, T.R.; Ben-David, M.A.; Friedman, E.; Solin, L.J.; Harris, E.E.; Gaffney, D.K.; Haffty, B.G.; Dawson, L.A.; et al. Ten-year multi-institutional results of breast-conserving surgery and radiotherapy in BRCA1/2-associated stage I/II breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 2437–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, L.J.; Strawderman, M.; Narod, S.A.; Oliviotto, I.; Eisen, A.; Dawson, L.; Gaffney, D.; Solin, L.J.; Nixon, A.; Garber, J.; et al. Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving treatment in women with breast cancer and germline BRCA1/2 mutations. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 18, 3360–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Broek, A.J.; Schmidt, M.K.; van ‘t Veer, L.J.; Oldenburg, H.S.A.; Rutgers, E.J.; Russell, N.S.; Smit, V.; Voogd, A.C.; Koppert, L.B.; Siesling, S.; et al. Prognostic Impact of Breast-Conserving Therapy Versus Mastectomy of BRCA1/2 Mutation Carriers Compared With Noncarriers in a Consecutive Series of Young Breast Cancer Patients. Ann. Surg. 2019, 270, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broek, A.J.; van ‘t Veer, L.J.; Hooning, M.J.; Cornelissen, S.; Broeks, A.; Rutgers, E.J.; Smit, V.T.; Cornelisse, C.J.; van Beek, M.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.L.; et al. Impact of Age at Primary Breast Cancer on Contralateral Breast Cancer Risk in BRCA1/2 Mutation Carriers. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Robson, M.; Gilewski, T.; Haas, B.; Levin, D.; Borgen, P.; Rajan, P.; Hirschaut, Y.; Pressman, P.; Rosen, P.P.; Lesser, M.L.; et al. BRCA-associated breast cancer in young women. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 1998, 16, 1642–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparano, J.A.; Gray, R.J.; Ravdin, P.M.; Makower, D.F.; Pritchard, K.I.; Albain, K.S.; Hayes, D.F.; Geyer, C.E., Jr.; Dees, E.C.; Goetz, M.P.; et al. Clinical and Genomic Risk to Guide the Use of Adjuvant Therapy for Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 2395–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, J.G.; Berglund, A.; Schell, M.J.; Mihaylov, I.; Fulp, W.J.; Yue, B.; Welsh, E.; Caudell, J.J.; Ahmed, K.; Strom, T.S.; et al. A genome-based model for adjusting radiotherapy dose (GARD): A retrospective, cohort-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschrich, S.A.; Fulp, W.J.; Pawitan, Y.; Foekens, J.A.; Smid, M.; Martens, J.W.; Echevarria, M.; Kamath, V.; Lee, J.H.; Harris, E.E.; et al. Validation of a radiosensitivity molecular signature in breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 5134–5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corn, B.W.; Feldman, D.B.; Wexler, I. The science of hope. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, e452–e459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Ferguson, A.; Corn, P.D.; Varadhan, R.; Ariely, D.; Stearns, V.; Smith, B.D.; Smith, T.J.; Corn, B.W. Developing Workshops to Enhance Hope Among Patients With Metastatic Breast Cancer and Oncologists: A Pilot Study. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021, Op2000744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | Year of Birth | Irradiation Therapy (AGE) | Reconstruction Reason, Type | Satisfaction Patients 1-10 | Baker Score | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

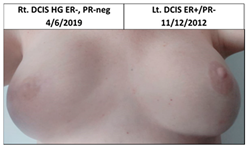

| 1B | 1972 | Bilateral 2013 (41) | 2019 CLT DCIS SSM Silicon | Rt-10/10 Lt. 7/10 | Rt-1 Lt-1 |  |

| 2B | 1964 | Bilateral 2015 (51) | 2020 CLT Ca. NSSM Silicon | Rt-10/10 Lt-10/10 | Rt-1 Lt-1 |  |

| 3B | 1947 | Bilateral 2010 (63) | 2015 Local Rec. SSM Silicon | Rt-7/10 Lt-7/10 | Rt-2 Lt-3 | Lt: IDC Gr.III, T1N0,TN 29/7/2009 Lt Rec: IDC Gr.III, T1N0,TN 6/11/2014 |

| Pt. declined to have her picture published | ||||||

| 4B * | 1972 | Bilateral 2010 (38) | 2017 CLT Ca. SSM Silicon | Rt-4/10 Lt-3/10 | Rt-4 Lt-4 |  |

| # | Year of Birth | Irradiation Therapy (AGE) | Reconstruction Reason, Type | Satisfaction Patients 1-10 | Baker Score | Photos |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1C | 1966 | Lt. breast 2010 (44) | 2012 Risk Reduc. SSM Silicon | Rt-8/10 Lt-8/10 | Rt-1 Lt-1 |  |

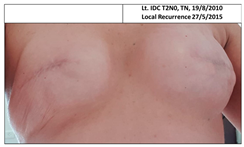

| 2C | 1965 | Lt. breast 2010 (45) | 2015 Local Rec. SSM Silicon | Rt-7/10 Lt-9/10 | Rt-4 Lt-2 |  |

| 3C | 1965 | Rt. Breast 2011 (46) | 2012 Risk Reduc. SSM Silicon | Rt-8/10 Lt-8/10 | Rt-2 Lt-1 |  |

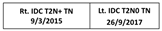

| 4C | 1970 | Lt. breast 2011 (41) | Lt- 2011 Rt- 2013 NSSM Silicon Bil. 2017- tear of implant | Rt-3/10 Lt-6/10 | Rt-3 Lt-2 |  |

| 5C | 1974 | Lt. breast 2014 (40) | 2015 Risk Reduc. SSM Silicon | Rt-10/10 Lt-10/10 | Rt-1 Lt-2 |  |

| 6C | 1973 | Rt. Breast 2016 (43) | 2018 CLT Ca. SSM Silicon | Rt-5/10 Lt-6/10 | Rt-4 Lt-3 |  |

| Pt. declined to have her picture published | ||||||

| 7C | 1978 | Lt. Breast 2017 (39) | 2019 Risk Reduc. NSSM Silicon | Rt-9/10 Lt-9/10 | Rt-2 Lt-2 |  |

| Reconstruction After Irradiation | Breast Cancer | Time from Irradiation to Reconstruction | Patient Satisf. 1–10 | Baker Score | Reconstruction No Irradiation | Breast Cancer | Patient Satisf. 1–10 | Baker Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1B Lt | 2012 | 6y 5mo | 7 | 1 | ||||

| 2B RT | 2014 | 5y | 10 | 1 | ||||

| 2B Lt | 2020 | 5y | 10 | 1 | ||||

| 3B Rt | No | 4y 9mo | 7 | 2 | ||||

| 3B Lt | 2009, 2014 | 4y 9mo | 7 | 3 | ||||

| 4B Rt | 2016 | 7y 5mo | 4 | 4 | ||||

| 4B Lt | 2009 | 7y 5mo | 3 | 4 | ||||

| 1C Lt | 2009 | 1y 7mo | 8 | 1 | 1C Rt | No | 8 | 1 |

| 2C Lt | 2010, 2015 | 5y 1mo | 9 | 2 | 2C Rt | No | 7 | 4 |

| 3C Rt | 2010 | 7mo | 8 | 2 | 3C Lt | No | 8 | 1 |

| 4C Rt | 2013 | 3 | 3 | |||||

| 5C Lt | 2013 | 12mo | 10 | 2 | 5C Rt | No | 10 | 1 |

| 6C Rt | 2015 | 2y 3mo | 5 | 4 | 6C Lt | 2017 | 6 | 3 |

| 7C Lt | 2016 | 1y 7mo | 9 | 2 | 7C Rt | No | 9 | 2 |

| Average | 7.64 | 2.14 | Average | 7.29 | 2.14 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ben David, M.A.; Evron, E.; Rasco, A.F.; Shai, A.; Corn, B.W. Risk-Reducing Mastectomy and Reconstruction Following Prophylactic Breast Irradiation: Hope Sustained. Cancers 2021, 13, 2694. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13112694

Ben David MA, Evron E, Rasco AF, Shai A, Corn BW. Risk-Reducing Mastectomy and Reconstruction Following Prophylactic Breast Irradiation: Hope Sustained. Cancers. 2021; 13(11):2694. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13112694

Chicago/Turabian StyleBen David, Merav A., Ella Evron, Adi F. Rasco, Ayelet Shai, and Benjamin W. Corn. 2021. "Risk-Reducing Mastectomy and Reconstruction Following Prophylactic Breast Irradiation: Hope Sustained" Cancers 13, no. 11: 2694. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13112694

APA StyleBen David, M. A., Evron, E., Rasco, A. F., Shai, A., & Corn, B. W. (2021). Risk-Reducing Mastectomy and Reconstruction Following Prophylactic Breast Irradiation: Hope Sustained. Cancers, 13(11), 2694. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13112694