Tele-Monitoring of Cancer Patients’ Rhythms during Daily Life Identifies Actionable Determinants of Circadian and Sleep Disruption

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

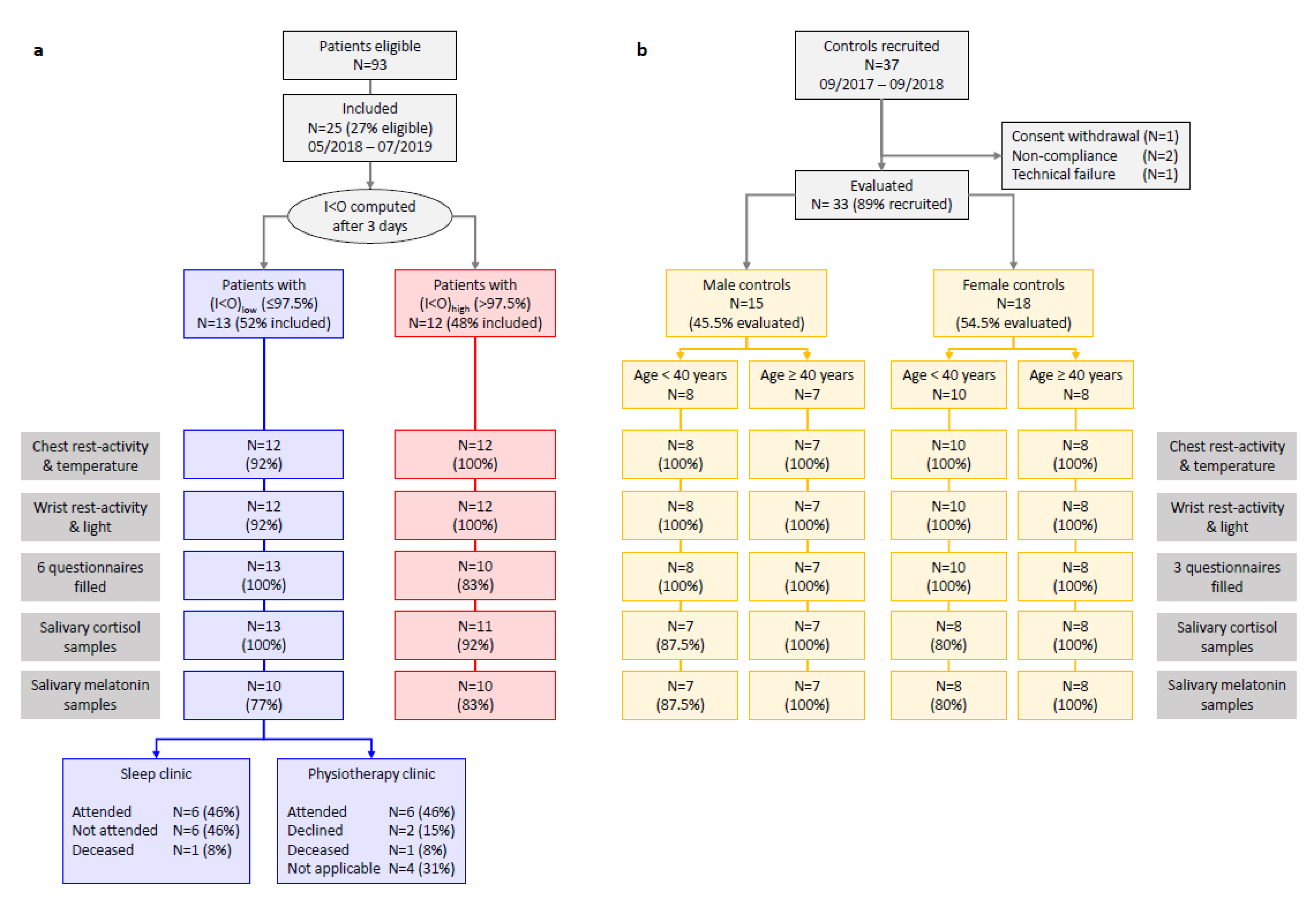

2.1. Study Flow, Participants’ Characteristics, Compliance, and Data Quality

2.1.1. Cancer Patients

2.1.2. Controls

2.1.3. Compliance

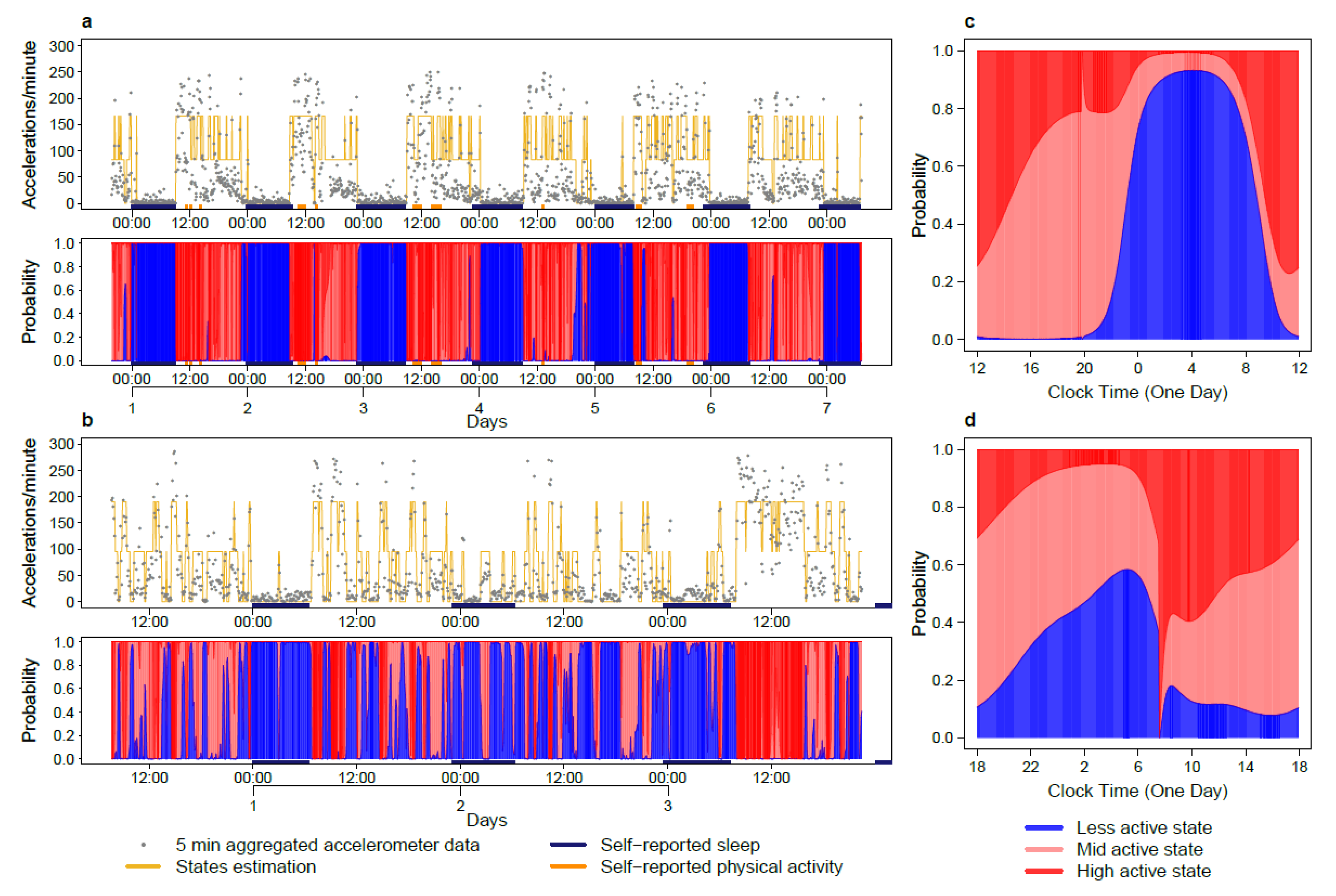

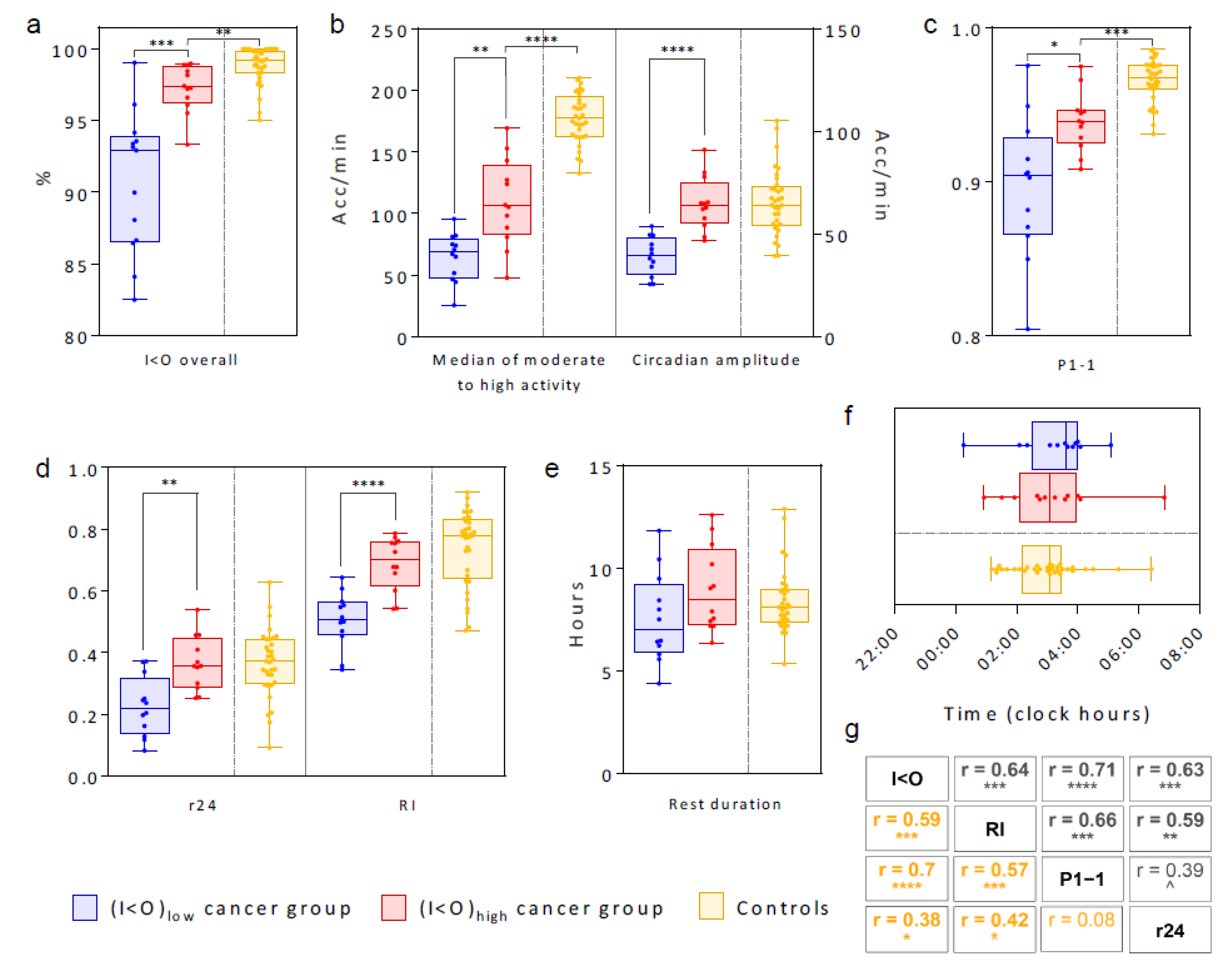

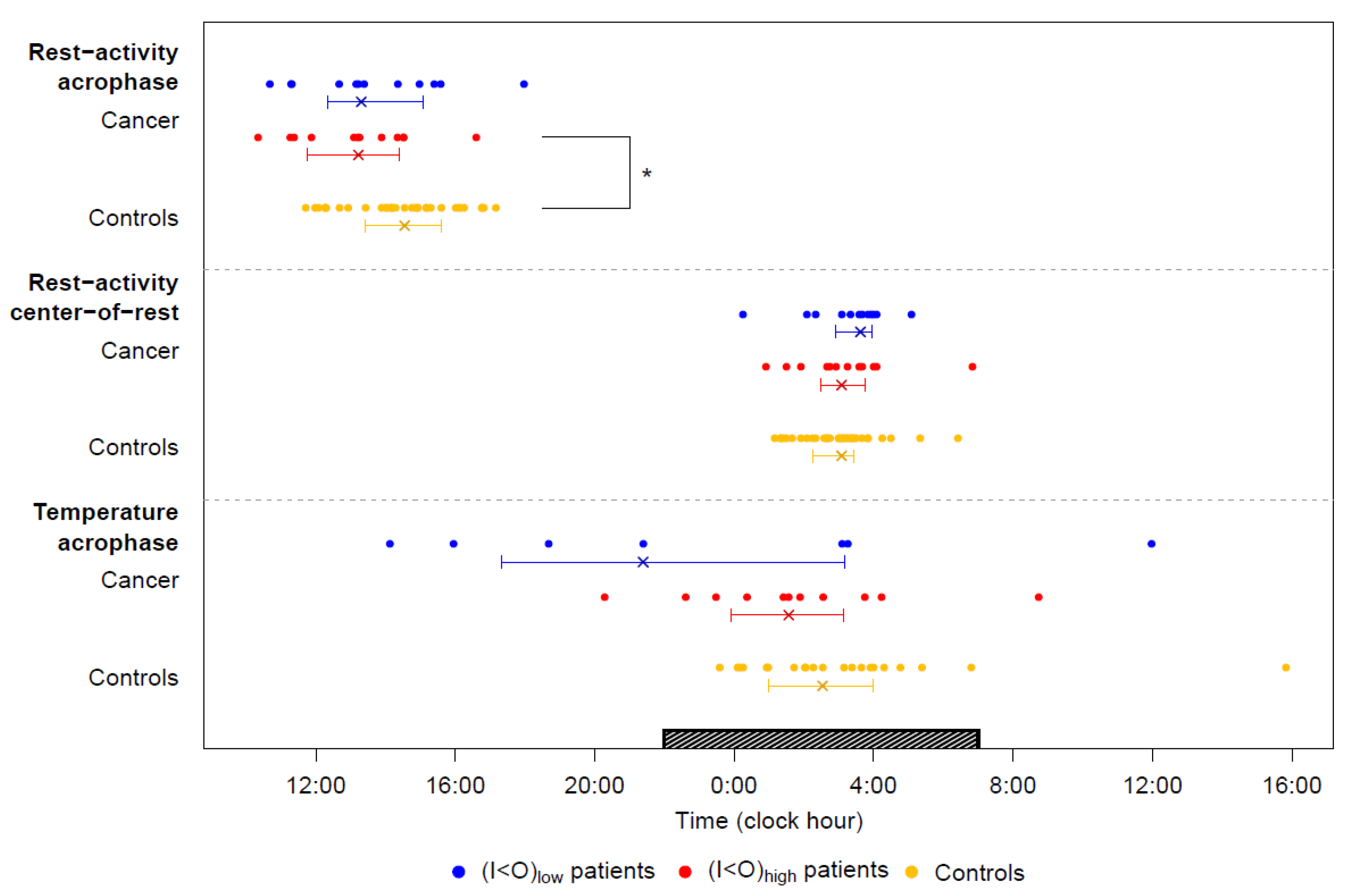

2.2. Tele-Transmitted Rest-Activity Patterns

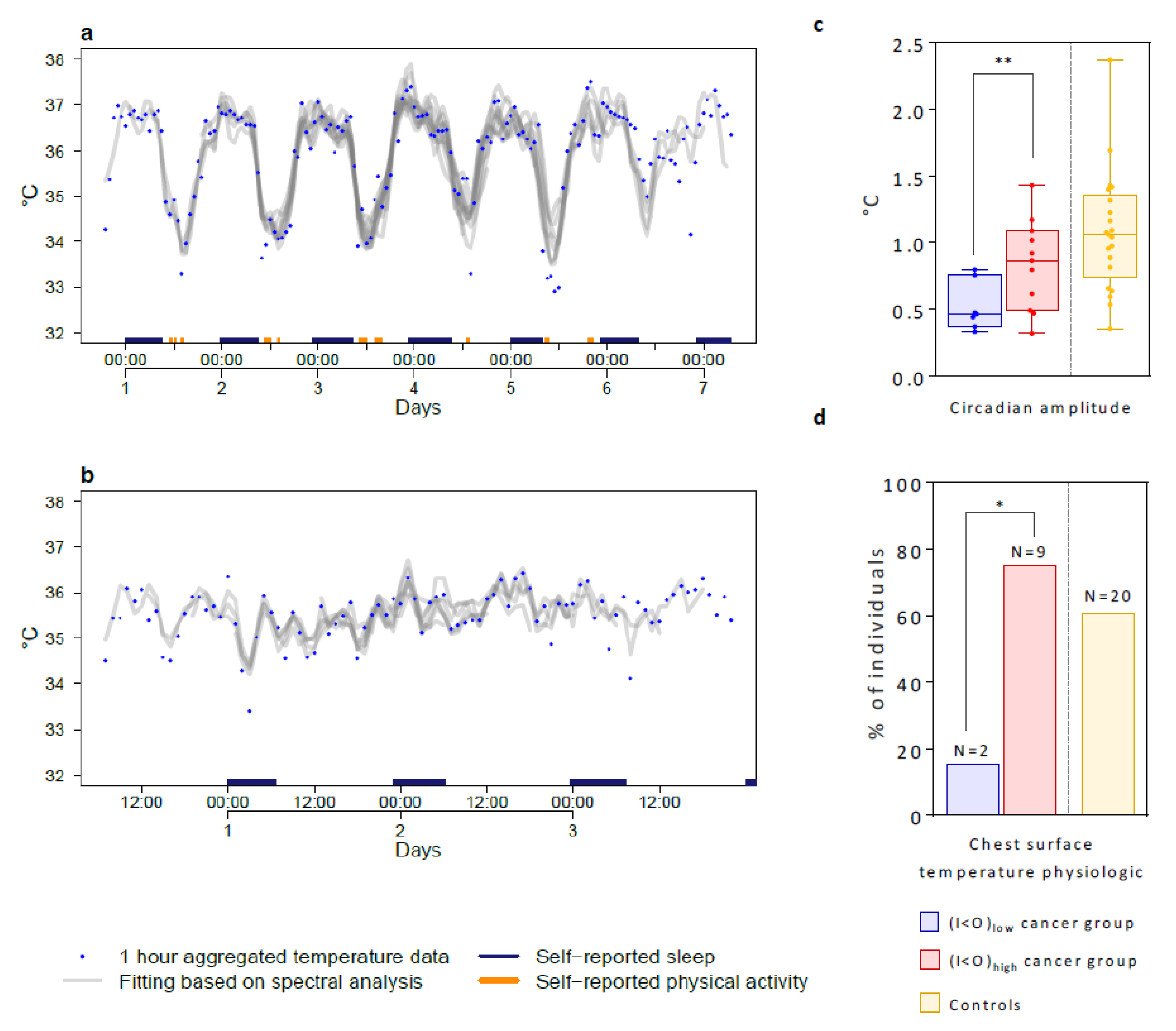

2.3. Tele-Transmitted Chest Surface Temperature Patterns

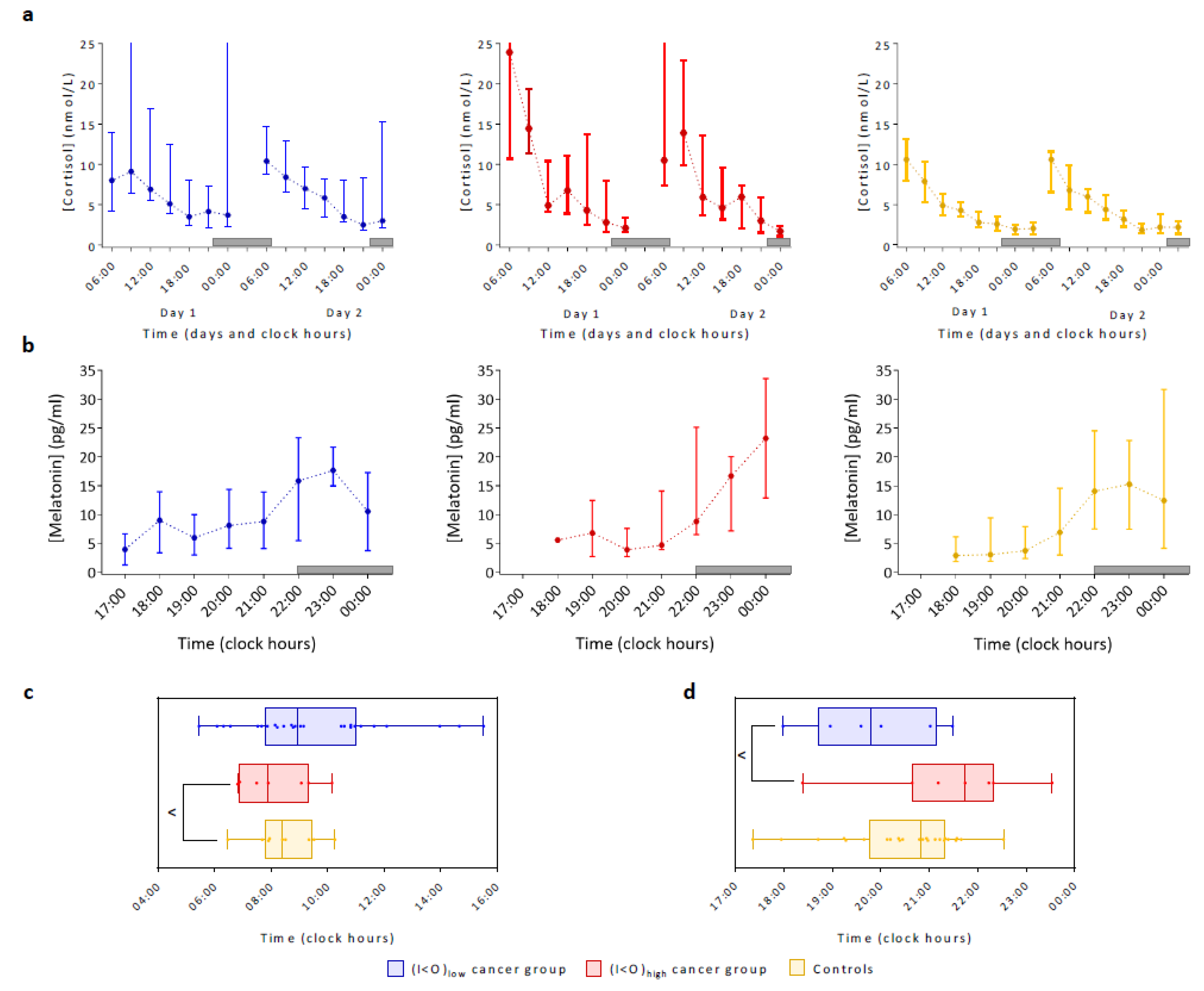

2.4. Lifestyle, Cortisol and Dim Light Melatonin Patterns

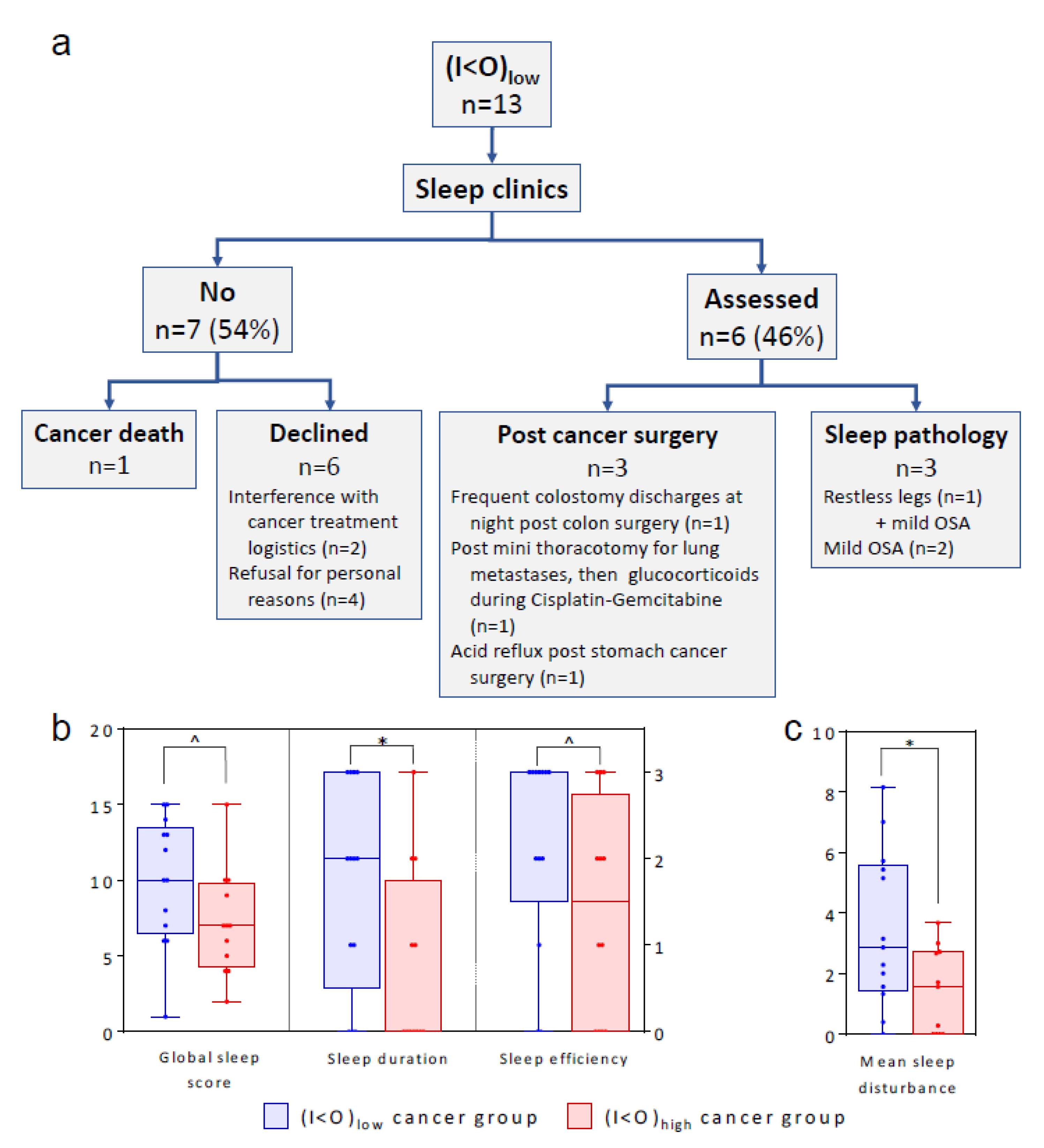

2.5. Sleep

2.6. Physical Activity

2.7. Relevance of Age, Sex and Cancer on Circadian Parameters

2.8. Regression Analysis to Identify Main Actionable Determinants of (I < O)

- The day-to-day variability in sleep duration estimated with hidden Markov modelling (HMM) (r = −0.53, p = 0.009);

- The self-reported exercise (r = 0.48, p = 0.02), the rest-activity circadian amplitude (r = 0.73, p < 0.0001), the median activity out-of-bed (r = 0.68, p = 0.0003), and the level of activity (r = 0.56, p = 0.005);

- The day-to-day variability in the self-reported retiring time (r = 0.49, p = 0.02);

- The physiologic chest temperature rhythm (24-h dominant period and nocturnal acrophase between 22:01 and 07:00, p = 0.03);

- The chronotype score (r = −0.43, p = 0.04).

- The HMM-estimated sleep duration variability (r = −0.53, p = 0.002);

- The rest-activity circadian amplitude (r = 0.36, p = 0.04);but in addition age (r = −0.48, p = 0.006).

3. Discussion

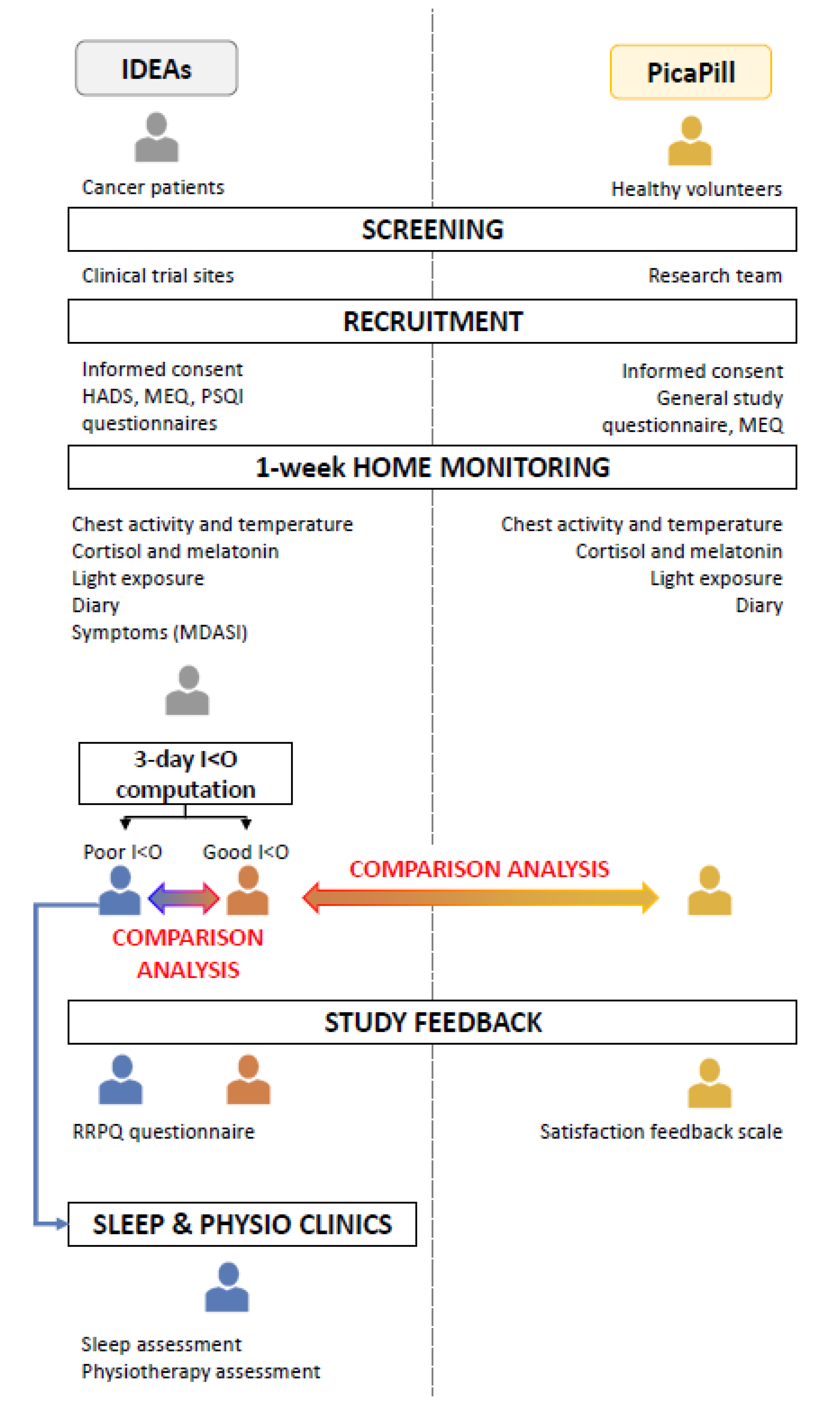

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Designs and Participants

4.2. Data Collection and Management

4.3. Statistical Methods

4.3.1. Circadian Parameters

- The mid values of the MA and HA states which indicate daily activity levels;

- The rhythm index (RI), with values ranging between 1, corresponding to best average quality and regularity of the IA state, and 0, corresponding to poor quality and absence of a consistent rest state in the pattern;

- The average center-of-rest time of the IA state;

- P1-1, the estimated probability of staying in the IA state (state 1); when having previously been in this state. P1-1 is positively correlated with I < O, while the probability [1-(P1-1)] serves as an estimate of rest interruption.

4.3.2. Spectral Analysis and Cosinor Modelling

4.3.3. DLMO Computation

4.3.4. Analysis of RACR Domain

4.4. Study Approval

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Grasselli, G.; Zangrillo, A.; Zanella, A.; Antonelli, M.; Cabrini, L.; Castelli, A.; Cereda, D.; Coluccello, A.; Foti, G.; Fumagalli, R.; et al. Baseline Characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the lombardy region, Italy. JAMA 2020, 323, 1574–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onder, G.; Rezza, G.; Brusaferro, S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA 2020, 323, 1775–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadashzadeh, S. The role of patient-centered medical home recognition in addressing public health priorities. Health Care Manag. 2019, 38, 124–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.; Tao, L.; Ford, E.W.; Beydoun, M.A.; Eid, S.M. The patient-centered oncology care on health care utilization and cost: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederroth, C.R.; Albrecht, U.; Bass, J.; Brown, S.A.; Dyhrfjeld-Johnsen, J.; Gachon, F.; Green, C.B.; Hastings, M.H.; Helfrich-Forster, C.; Hogenesch, J.B.; et al. Medicine in the fourth dimension. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innominato, P.F.; Roche, V.P.; Palesh, O.G.; Ulusakarya, A.; Spiegel, D.; Levi, F.A. The circadian timing system in clinical oncology. Ann. Med. 2014, 46, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, M.H.; Reddy, A.B.; Maywood, E.S. A clockwork web: Circadian timing in brain and periphery, in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003, 4, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallmann, R.; Okyar, A.; Levi, F. Dosing-time makes the poison: Circadian regulation and pharmacotherapy. Trends Mol. Med. 2016, 22, 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roenneberg, T.; Merrow, M. The circadian clock and human health. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, R432–R443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innominato, P.F.; Focan, C.; Gorlia, T.; Moreau, T.; Garufi, C.; Waterhouse, J.; Giacchetti, S.; Coudert, B.; Iacobelli, S.; Genet, D.; et al. Circadian rhythm in rest and activity: A biological correlate of quality of life and a predictor of survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 4700–4707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innominato, P.F.; Komarzynski, S.; Palesh, O.G.; Dallmann, R.; Bjarnason, G.A.; Giacchetti, S.; Ulusakarya, A.; Bouchahda, M.; Haydar, M.; Ballesta, A.; et al. Circadian rest-activity rhythm as an objective biomarker of patient-reported outcomes in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 4396–4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levi, F.; Dugue, P.A.; Innominato, P.; Karaboue, A.; Dispersyn, G.; Parganiha, A.; Giacchetti, S.; Moreau, T.; Focan, C.; Waterhouse, J.; et al. Wrist actimetry circadian rhythm as a robust predictor of colorectal cancer patients survival. Chronobiol. Int. 2014, 31, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mormont, M.C.; Waterhouse, J.; Bleuzen, P.; Giacchetti, S.; Jami, A.; Bogdan, A.; Lellouch, J.; Misset, J.L.; Touitou, Y.; Levi, F. Marked 24-h rest/activity rhythms are associated with better quality of life, better response, and longer survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer and good performance status. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000, 6, 3038–3045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sephton, S.E.; Sapolsky, R.M.; Kraemer, H.C.; Spiegel, D. Diurnal cortisol rhythm as a predictor of breast cancer survival. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2000, 92, 994–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innominato, P.; Komarzynski, S.; Karaboue, A.; Ulusakarya, A.; Bouchahda, M.; Haydar, M.; Bossevot-Desmaris, R.; Mocquery, M.; Plessis, V.; Levi, F. Home-based e-health platform for multidimensional telemonitoring of symptoms, body weight, sleep, and circadian activity: Relevance for chronomodulated administration of irinotecan, fluorouracil-leucovorin, and oxaliplatin at home-results from a pilot study. JCO Clin. Cancer Inf. 2018, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innominato, P.F.; Komarzynski, S.; Mohammad-Djafari, A.; Arbaud, A.; Ulusakarya, A.; Bouchahda, M.; Haydar, M.; Bossevot-Desmaris, R.; Plessis, V.; Mocquery, M.; et al. Clinical relevance of the first domomedicine platform securing multidrug chronotherapy delivery in metastatic cancer patients at home: The inCASA European project. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natale, V.; Innominato, P.F.; Boreggiani, M.; Tonetti, L.; Filardi, M.; Parganiha, A.; Fabbri, M.; Martoni, M.; Levi, F. The difference between in bed and out of bed activity as a behavioral marker of cancer patients: A comparative actigraphic study. Chronobiol. Int. 2015, 32, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minors, D.; Akerstedt, T.; Atkinson, G.; Dahlitz, M.; Folkard, S.; Levi, F.; Mormont, C.; Parkes, D.; Waterhouse, J. The difference between activity when in bed and out of bed. I. healthy subjects and selected patients. Chronobiol. Int. 1996, 13, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innominato, P.F.; Mormont, M.C.; Rich, T.A.; Waterhouse, J.; Levi, F.A.; Bjarnason, G.A. Circadian disruption, fatigue, and anorexia clustering in advanced cancer patients: Implications for innovative therapeutic approaches. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2009, 8, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mormont, M.C.; Waterhouse, J. Contribution of the rest-activity circadian rhythm to quality of life in cancer patients. Chronobiol. Int. 2002, 19, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.P.; Lin, C.C. Correlation between rest-activity rhythm and survival in cancer patients experiencing pain. Chronobiol. Int. 2014, 31, 926–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innominato, P.F.; Giacchetti, S.; Bjarnason, G.A.; Focan, C.; Garufi, C.; Coudert, B.; Iacobelli, S.; Tampellini, M.; Durando, X.; Mormont, M.C.; et al. Prediction of overall survival through circadian rest-activity monitoring during chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 131, 2684–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komarzynski, S.; Huang, Q.; Innominato, P.F.; Maurice, M.; Arbaud, A.; Beau, J.; Bouchahda, M.; Ulusakarya, A.; Beaumatin, N.; Breda, G.; et al. Relevance of a mobile internet platform for capturing inter- and intrasubject variabilities in circadian coordination during daily routine: Pilot study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, M.J.; Finkenstadt, B.; Roche, V.; Levi, F.; Gould, P.D.; Foreman, J.; Halliday, K.; Hall, A.; Rand, D.A. Inference on periodicity of circadian time series. Biostatistics 2013, 14, 792–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Cohen, D.; Komarzynski, S.; Li, X.M.; Innominato, P.; Levi, F.; Finkenstadt, B. Hidden markov models for monitoring circadian rhythmicity in telemetric activity data. J. R. Soc. Interface 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborn, J.; Ajakaiye, A.; Cooksley, T.; Subbe, C.P. Do mHealth applications improve clinical outcomes of patients with cancer? A critical appraisal of the peer-reviewed literature. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 1469–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathbone, A.L.; Clarry, L.; Prescott, J. Assessing the efficacy of mobile health apps using the basic principles of cognitive behavioral therapy: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, E.; Dueck, A.C.; Rogak, L.J.; Minasian, L.M.; Kelly, W.K.; O′Mara, A.M.; Denicoff, A.M.; Seisler, D.; Atherton, P.J.; Paskett, E.; et al. Feasibility assessment of patient reporting of symptomatic adverse events in multicenter cancer clinical trials. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benze, G.; Nauck, F.; Alt-Epping, B.; Gianni, G.; Bauknecht, T.; Ettl, J.; Munte, A.; Kretzschmar, L.; Gaertner, J. PROutine: A feasibility study assessing surveillance of electronic patient reported outcomes and adherence via smartphone app in advanced cancer. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2019, 8, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, D.L.; Blonquist, T.M.; Nayak, M.M.; Grenon, N.; Momani, T.G.; McCleary, N.J. Self-care support for patients with gastrointestinal cancer: iCancerHealth. Appl. Clin. Inf. 2018, 9, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, H.J.; Wyatt, J.K.; Park, M.; Fogg, L.F. Home circadian phase assessments with measures of compliance yield accurate dim light melatonin onsets. Sleep 2015, 38, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, E.; Kupfer, D.J.; Thase, M.E.; Mallinger, A.G.; Swartz, H.A.; Fagiolini, A.M.; Grochocinski, V.; Houck, P.; Scott, J.; Thompson, W.; et al. Two-year outcomes for interpersonal and social rhythm therapy in individuals with bipolar I disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiat. 2005, 62, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, V.D.; Panda, S. Fasting, Circadian Rhythms, and Time-Restricted Feeding in Healthy Lifespan. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 1048–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, P.M. Modified-release hydrocortisone: Is it time to change clinical practice? J. Endocr. Soc. 2019, 3, 1150–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.M.; Kern, P.A.; Bush, H.M.; McQuerry, K.J.; Black, W.S.; Clasey, J.L.; Pendergast, J.S. Circadian rhythm phase shifts caused by timed exercise vary with chronotype. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e134270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, R.V.; Boyd, K.M.; Webb, D.J. The revision of the declaration of helsinki: Past, present and future. Br. J. Clin. Pharm. 2004, 57, 695–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarzynski, S.; Bolborea, M.; Huang, Q.; Finkenstadt, B.; Levi, F. Predictability of individual circadian phase during daily routine for medical applications of circadian clocks. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e130423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, J.A.; Ostberg, O. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int. J. Chronobiol. 1976, 4, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kassam-Adams, N.; Newman, E. The reactions to research participation questionnaires for children and for parents (RRPQ-C and RRPQ-P). Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2002, 24, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F., 3rd; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleeland, C.S.; Mendoza, T.R.; Wang, X.S.; Chou, C.; Harle, M.T.; Morrissey, M.; Engstrom, M.C. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: The M.D. anderson symptom inventory. Cancer 2000, 89, 1634–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruehland, W.R.; Rochford, P.D.; O′Donoghue, F.J.; Pierce, R.J.; Singh, P.; Thornton, A.T. The new AASM criteria for scoring hypopneas: Impact on the apnea hypopnea index. Sleep 2009, 32, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornelissen, G. Cosinor-based rhythmometry. Biol. Med. Model. 2014, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoubir, A.M.; Iskander, D.R. Bootstrap Techniques for Signal Processing; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

| Number of Participants | Cancer Patients 25 | (I < O)low Cancer Group 13 | (I < O)high Cancer Group 12 | Controls 33 | p-Values 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (I < O)low vs. (I < O)high (Cancer) | (I < O)high (Cancer) vs. Controls | |||||

| Sex | ||||||

| M | 21 (84.0) | 11 (84.6) | 10 (83.3) | 15 (45.5) | 1 | 0.04 * |

| F | 4 (16.0) | 2 (15.4) | 2 (16.7) | 18 (54.5) | ||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| Median | 66 | 66 | 70 | 35 | 0.568 | <0.0001 **** |

| Range | 40–82 | 40–80 | 42–82 | 21–78 | ||

| BMI | ||||||

| Median | 27.5 | 27.5 | 26.9 | 24.4 | 0.511 | 0.216 |

| Range | 19.8–38.8 | 22.4–38.8 | 19.8–33.7 | 18.9–42.0 | ||

| (I < O)72h (%) | ||||||

| Median | 97.4 | 90.4 | 98.7 | NA | 0.0017 ** | NA |

| Range | 67.6–100 | 67.6–97.4 | 97.7–100 | NA | ||

| Work status | ||||||

| Employed or self-employed | 8 (32.0) | 5 (38.5) | 3 (25.0) | 15 (45.5) | 0.673 | 0.002 ** |

| Student | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 11 (33.3) | ||

| Retired or not working | 17 (68.0) | 8 (61.5) | 9 (75.0) | 7 (21.2) | ||

| Chronotype | ||||||

| Definite morning | 3 (12) | 1 (8) | 2 (17) | 5 (15.2) | 0.408 | 0.594 |

| Moderate morning | 12 (48) | 8 (62) | 4 (33) | 10 (30.3) | ||

| Intermediate | 9 (36) | 4 (31) | 5 (42) | 15 (45.5) | ||

| Moderate evening | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (9.1) | ||

| Not available | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | ||

| Ongoing medical condition (other than cancer) | ||||||

| None | 8 (32.0) | 3 (23.1) | 5 (41.7) | 25 (75.8) | 0.362 | 0.003 ** |

| 1–2 | 8 (32.0) | 6 (46.2) | 2 (16.7) | 7 (21.2) | ||

| ≥ 3 | 9 (36.0) | 4 (30.8) | 5 (41.7) | 1 (3.0) | ||

| Concurrent medications (apart from cancer treatments) | ||||||

| 0 | 3 (12.0) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (16.7) | 25 (75.8) | 0.866 | < 0.0001 **** |

| 1–2 | 12 (48.0) | 7 (53.8) | 5 (41.7) | 8 (24.2) | ||

| ≥ 3 | 10 (40.0) | 5 (38.5) | 5 (41.7) | 0 (0) | ||

| Site of primary tumor | ||||||

| Colorectal | 14 (56.0) | 5 (38.5) | 9 (75.0) | NA | 0.111 | NA |

| Other | 11 (44.0) | 8 (61.5) | 3 (25.0) | NA | ||

| Cancer status | ||||||

| No residual tumor | 2 (8.0) | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0) | NA | 0.561 | NA |

| Locally advanced cancer | 6 (24.0) | 3 (23.1) | 3 (25.0) | NA | ||

| Metastatic disease | 17 (68.0) | 8 (61.5) | 9 (75.0) | NA | ||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||

| 0 | 8 (32.0) | 5 | 3 | NA | 0.861 | NA |

| 1–2 | 13 (52.0) | 6 | 7 | NA | ||

| ≥ 3 | 4 (16.0) | 2 | 2 | NA | ||

| Main metastatic sites | ||||||

| Liver | 9 (36.0) | 3 (23.1) | 6 (50.0) | NA | 0.721 | NA |

| Lymph nodes | 9 (36.0) | 5 (38.5) | 4 (33.3) | NA | ||

| Lungs | 8 (32.0) | 5 (38.5) | 3 (25.0) | NA | ||

| Other | 5 (20.0) | 2 (15.4) | 3 (25.0) | NA | ||

| Prior cancer treatments | ||||||

| Surgery | 13 (52.0) | 6 (46.1) | 7 (58.3) | NA | 0.508 | NA |

| Radiotherapy | 8 (32.0) | 2 (15.4) | 6 (50.0) | NA | ||

| Chemotherapy | 20 (80.0) | 10 (76.9) | 10 (83.3) | NA | ||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lévi, F.; Komarzynski, S.; Huang, Q.; Young, T.; Ang, Y.; Fuller, C.; Bolborea, M.; Brettschneider, J.; Fursse, J.; Finkenstädt, B.; et al. Tele-Monitoring of Cancer Patients’ Rhythms during Daily Life Identifies Actionable Determinants of Circadian and Sleep Disruption. Cancers 2020, 12, 1938. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12071938

Lévi F, Komarzynski S, Huang Q, Young T, Ang Y, Fuller C, Bolborea M, Brettschneider J, Fursse J, Finkenstädt B, et al. Tele-Monitoring of Cancer Patients’ Rhythms during Daily Life Identifies Actionable Determinants of Circadian and Sleep Disruption. Cancers. 2020; 12(7):1938. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12071938

Chicago/Turabian StyleLévi, Francis, Sandra Komarzynski, Qi Huang, Teresa Young, Yeng Ang, Claire Fuller, Matei Bolborea, Julia Brettschneider, Joanna Fursse, Bärbel Finkenstädt, and et al. 2020. "Tele-Monitoring of Cancer Patients’ Rhythms during Daily Life Identifies Actionable Determinants of Circadian and Sleep Disruption" Cancers 12, no. 7: 1938. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12071938

APA StyleLévi, F., Komarzynski, S., Huang, Q., Young, T., Ang, Y., Fuller, C., Bolborea, M., Brettschneider, J., Fursse, J., Finkenstädt, B., White, D. P., & Innominato, P. (2020). Tele-Monitoring of Cancer Patients’ Rhythms during Daily Life Identifies Actionable Determinants of Circadian and Sleep Disruption. Cancers, 12(7), 1938. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12071938