Experimental Study on Acoustic Emission Signals Under Different Processing States of Laser-Assisted Machining of SiC Ceramics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Materials and Equipment

3. Research Fundamentals and Experimental Methods

3.1. Sources of AE Signals

3.2. Analysis of Characterization Methods for Softening Degree and Signal Feature Extraction

3.3. Experimental Scheme Design

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Machined Surface Morphology and Processing State

4.2. AE Signal Processing and Analysis

4.2.1. Signal Denoising

4.2.2. Frequency Spectrum Analysis

4.2.3. Energy Spectrum Analysis

4.2.4. Softening Degree Characterization and Processing State Identification

5. Conclusions

- Single-factor experiments on laser power were conducted to analyze the machined surface morphology of SiC ceramics using 3D digital microscopy and SEM. Results indicate that three distinct processing states correspond to specific laser power ranges: brittle state (0–185 W), plastic state (185–225 W), and thermal damage state (>225 W). The critical transition points between brittle and ductile behavior occur at 185 W, while the transition from plastic to thermal damage occurs at 225 W.

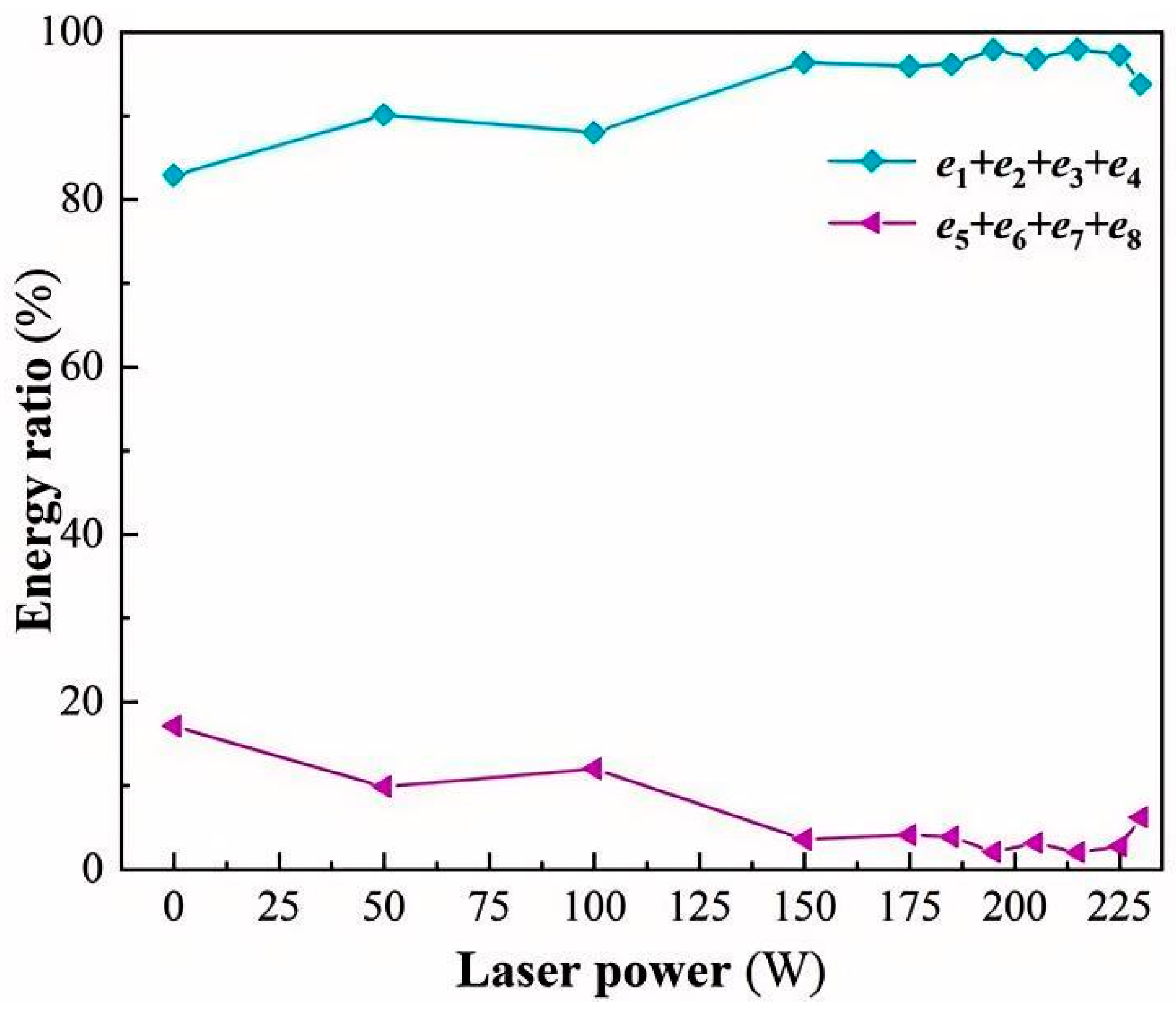

- Based on single-factor laser power experiments, the collected AE signals were denoised using the sym8 wavelet basis function, followed by frequency spectrum and energy spectrum analysis. The frequency spectrum analysis reveals that as the laser power increases, the frequency corresponding to the maximum amplitude initially decreases significantly, then stabilizes, and finally exhibits a slight increase. This trend corresponds respectively to the brittle, plastic, and thermal damage processing states. A similar pattern is observed for the amplitude at the characteristic frequency of 515 kHz in the high-frequency domain. The energy spectrum analysis indicates that the energy ratio of the low-frequency band (0–500 kHz) first rises gradually, remains stable, and then decreases slightly with increasing laser power, again corresponding to the brittle, plastic, and thermal damage states.

- This paper proposes a characterization method for softening degree, and the plastic processing state of the materials can be identified by the softening degree. The softening degree is defined as the sum of the energy ratios of the characteristic frequency band 2 (125–250 kHz) and frequency band 4 (375–500 kHz) in the low-frequency band. When the softening degree is not less than 84.89%, the cutting process is in a plastic state; when the softening degree is less than 84.89%, the cutting process is in a non-plastic state.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, D.R.; Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Yu, Y.; Shen, C.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Z. Laser drilling in silicon carbide and silicon carbide matrix composites. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 170, 110166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Y.; Lin, W. Temperature field simulation and optimization of processing parameters for laser-assisted machining of 3Y-TZP ceramics. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 175, 110878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Zhou, X.; Song, J. Experimental investigation on cutting force and machining parameters optimization in in-situ laser-assisted machining of glass–ceramic. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 169, 110109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, K.; Yan, G.; Luo, X.; Gilchrist, M.D.; Fang, F. Advances in laser assisted machining of hard and brittle materials. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 58, 677–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; He, T.; Wen, D.; Li, T.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Ding, Y.; Tang, X.; Yang, Z. Improving zirconia ceramics grinding surface integrity through innovative laser bionic surface texturing. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 32081–32097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Du, S.; Shang, Y.; Yan, C.; Chang, J.; Xu, T. Assessment and optimization of grinding process on zirconia ceramic using response surface method. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2024, 33, 7154–7163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Li, X.; Mu, D.; Lawn, B.R. Science and art of ductile grinding of brittle solids. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2021, 161, 103675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q.; Han, J.; Khan, A.M.; Ma, R.; He, B.; Kong, L.; Li, Q.; Ding, K.; Ahmad, W.; Lei, W. Experimental investigation on large-aspect-ratio zirconia ceramic microchannels by waterjet-assisted laser processing. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 111, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, J.; Fang, Q.; Chen, J.; Xie, C.; Liu, Y.; Wen, P. Investigation of subsurface damage considering the abrasive particle rotation in brittle material grinding. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 90, 2461–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zeng, J.; Xie, X.; Chen, C.; Huang, Y. Laser machining of silicon carbide: Current status, applications and challenges. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 191, 113376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ke, J.; Yin, T.; Yip, W.S.; Zhang, J.; To, S.; Xu, J. Cutting mechanism of reaction-bonded silicon carbide in laser-assisted ultra-precision machining. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2024, 203, 104219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.F.; Zhang, H.Z.; Wang, Y.; Xie, C. Simulation and experimental study on temperature fields for laser assisted machining of silicon nitride. Key Eng. Mater. 2010, 419–420, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Song, H.; Yang, Z.; Ren, G.; Xiao, J.; Chen, X.; Xu, J. Thermal field modeling and experimental analysis in laser-assisted machining of fused silica. Silicon 2021, 13, 3163–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Zhou, X.; Chen, S.; Jiang, S.; Gao, K.; He, X. Measurement of Thermal Properties and Numerical Simulation of Temperature Distribution in Laser-assisted Machining of Glass-ceramic. Silicon 2022, 14, 12155–12164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, F.; Luo, X.; Chang, W.; Cai, Y.; Zhong, W.; Ding, F. Material removal mechanism of laser-assisted grinding of RB-SiC ceramics and process optimization. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 39, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, V.; Ayanleye, S.; Kazemirad, S.; Sassani, F.; Adamopoulos, S. Acoustic emission monitoring of wood materials and timber structures: A critical review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 350, 128877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Obaidi, S.M.A.; Leong, M.S.; Hamzah, R.I.R.; Abdelrhman, A.M. A review of acoustic emission technique for machinery condition monitoring: Defects detection & diagnostic. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 229–231, 1476–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnþórsson, R. Hit detection and determination in AE bursts. In Acoustic Emission—Research and Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S.; Komvopoulos, K. Correlation between acoustic emission and wear of multi-layer ceramic coated carbide tools. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng.-Trans. Asme 1997, 119, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, M.; Kanthababu, M.; Rajurkar, K.P. Investigations on the effects of tool wear on chip formation mechanism and chip morphology using acoustic emission signal in the microendmilling of aluminum alloy. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 77, 1499–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangjitsitcharoen, S.; Lohasiriwat, H. Intelligent monitoring and prediction of tool wear in CNC turning by utilizing wavelet transform. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 99, 2219–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Y.S.; Arif, A.F.M.; Veldhuis, S.C. Application of the wavelet transform to acoustic emission signals for built-up edge monitoring in stainless steel machining. Measurement 2020, 154, 107478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.B.; Ammula, S.C. Real-time acoustic emission monitoring for surface damage in hard machining. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2005, 45, 1622–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindra, D.; Virkar, S.; Patten, J. Ductile mode micro laser assisted machining of silicon carbide (SiC). In Properties and Applications of Silicon Carbide; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2011; Volume 23, pp. 506–535. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, C.; Zhao, Y.; Meng, J.; Dai, D.; Liu, Q.; Liu, G.; Zhou, H.; Song, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X. Experimental study of the thermal effects and processing in CW laser-assisted turning of SiC ceramics. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 125, 4467–4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Li, Z.; Zhao, C.; Yu, H.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, H.; Dai, D. Experimental study of plastic cutting in laser-assisted machining of SiC ceramics. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 169, 110098. [Google Scholar]

| Items | SiC |

|---|---|

| Elastic modulus (GPa) | 290 |

| Vickers hardness (kgf·mm−2) | 2100 |

| Compressive strength (MPa) | 3000 |

| Fracture toughness (MPa·m1/2) | 4 |

| Thermal expansion coeff. × 10−6/℃ | 4.5 |

| Thermal conductivity (W/mK) | 80 |

| Melting point (K) | 3100 |

| Specific heat capacity (J/kgK) | 1100 |

| Density (g/cm3) | 3.15 |

| Signal Types | Sources |

|---|---|

| Continuous AE signals (low-frequency) | Formation process (shear process) of chips |

| Rubbing between the cutting tool and chips or the workpiece | |

| Wear of the cutting tool | |

| Transient AE signals (high-frequency) | Thermal cracks due to thermal stresses caused by laser preheating |

| Collisions and breakages of chips | |

| Formation and removal of built-up edges | |

| Damage to the cutting tool (breakage, chipping, flaking, etc.) | |

| Entanglement of chips onto the workpiece or cutting tool | |

| Vibrations of the cutting tool |

| No. | Process Parameter | Value Range |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Laser power (W) | 0, 50, 100, 150, 175, 185, 195, 205, 215, 225 |

| 2 | Rotational speed (r/min) | 1620 |

| 3 | Feed speed (mm/min) | 3 |

| 4 | Cutting depth (mm) | 0.15 |

| Items | haar | coif2 | db6 | sym6 | sym8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNR | 16.236 | 20.883 | 20.969 | 20.977 | 21.033 |

| MSE | 0.051 | 0.0174 | 0.01708 | 0.01706 | 0.0168 |

| RMSES | 0.225 | 0.132 | 0.1307 | 0.1306 | 0.1298 |

| No. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laser power | 0 | 50 | 100 | 150 | 175 | 185 | 195 | 205 | 215 | 225 | 230 |

| Maximum amplitude (×10−2) | 12.25 | 5.50 | 10.47 | 2.75 | 3.26 | 5.1 | 4.02 | 5.12 | 3.95 | 3.12 | 4.11 |

| Frequency (kHz) | 513.8 | 214.4 | 168.7 | 128.4 | 218.1 | 180.5 | 195.1 | 205.4 | 180.8 | 368.4 | 208.6 |

| No. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laser power | 0 | 50 | 100 | 150 | 175 | 185 | 195 | 205 | 215 | 225 | 230 |

| Frequency (kHz) | 513.8 | 514.7 | 512.2 | 515.5 | 516.4 | 514.1 | 514.9 | 514.9 | 515.7 | 515.1 | 514.8 |

| Amplitude (×10−2) | 12.25 | 0.76 | 2.80 | 0.89 | 1.47 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.26 |

| No. | Laser Power | Frequency Band Energy Ratio (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e1 | e2 | e3 | e4 | e5 | e6 | e7 | e8 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 1.74 | 50.51 | 13.21 | 17.43 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 13.08 | 2.30 |

| 2 | 50 | 4.96 | 52.19 | 7.13 | 25.85 | 1.26 | 1.34 | 5.01 | 2.26 |

| 3 | 100 | 2.35 | 61.24 | 6.77 | 17.64 | 1.17 | 1.52 | 6.17 | 3.16 |

| 4 | 150 | 16.16 | 60.43 | 4.26 | 15.54 | 0.15 | 0.26 | 2.49 | 0.70 |

| 5 | 175 | 8.16 | 60.93 | 4.60 | 22.20 | 0.19 | 0.34 | 2.57 | 1.00 |

| 6 | 185 | 3.89 | 61.85 | 7.36 | 23.04 | 0.34 | 0.56 | 1.47 | 1.50 |

| 7 | 195 | 4.04 | 66.72 | 4.35 | 22.81 | 0.07 | 0.22 | 1.01 | 0.77 |

| 8 | 205 | 2.03 | 68.85 | 2.77 | 23.16 | 0.23 | 0.52 | 1.23 | 1.20 |

| 9 | 215 | 4.44 | 56.67 | 7.17 | 29.68 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 1.22 | 0.69 |

| 10 | 225 | 2.82 | 44.05 | 9.16 | 41.24 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 1.05 | 1.31 |

| 11 | 230 | 4.61 | 48.36 | 9.63 | 31.17 | 1.09 | 1.06 | 2.21 | 1.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cao, C.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, X.; Cui, X. Experimental Study on Acoustic Emission Signals Under Different Processing States of Laser-Assisted Machining of SiC Ceramics. Micromachines 2026, 17, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010042

Cao C, Zhao Y, Hu X, Cui X. Experimental Study on Acoustic Emission Signals Under Different Processing States of Laser-Assisted Machining of SiC Ceramics. Micromachines. 2026; 17(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Chen, Yugang Zhao, Xiukun Hu, and Xiao Cui. 2026. "Experimental Study on Acoustic Emission Signals Under Different Processing States of Laser-Assisted Machining of SiC Ceramics" Micromachines 17, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010042

APA StyleCao, C., Zhao, Y., Hu, X., & Cui, X. (2026). Experimental Study on Acoustic Emission Signals Under Different Processing States of Laser-Assisted Machining of SiC Ceramics. Micromachines, 17(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010042