Experimental Research Progress on Gas–Liquid Flow and Heat Transfer Characteristics in Micro Pulsating Heat Pipes

Abstract

1. Introduction

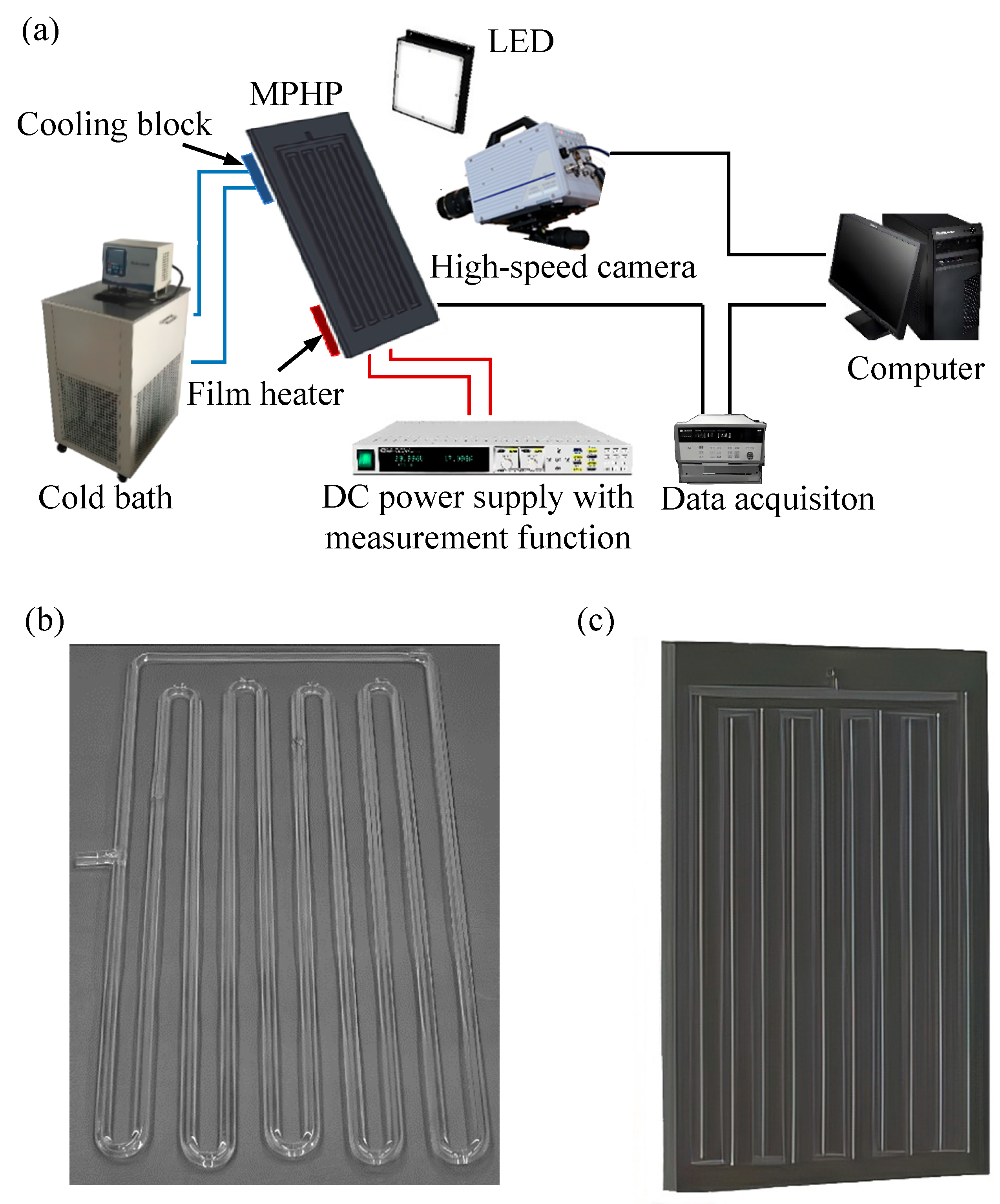

2. Experimental Research Methods

3. Experimental Study on Flow Characteristics of the MPHP

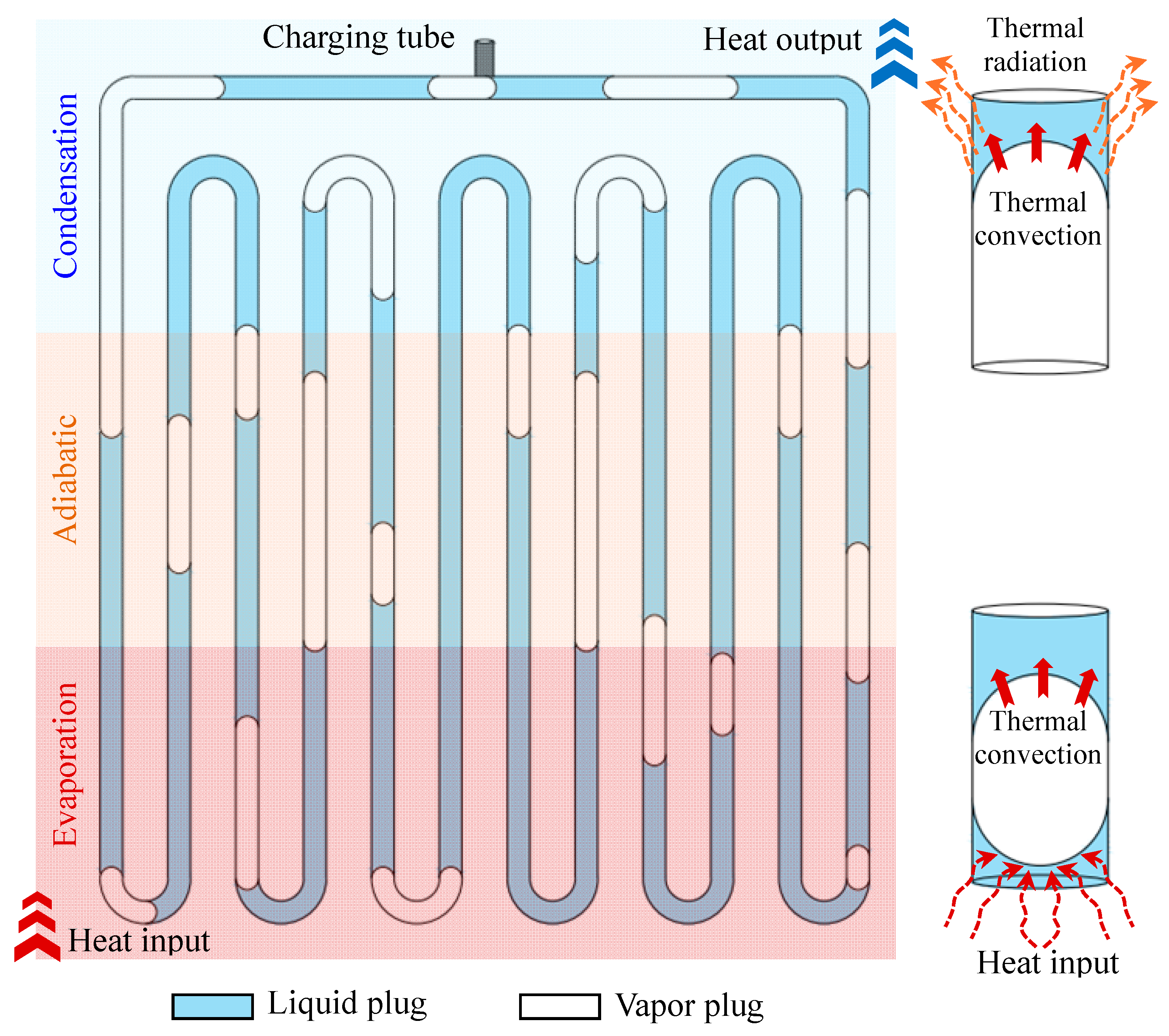

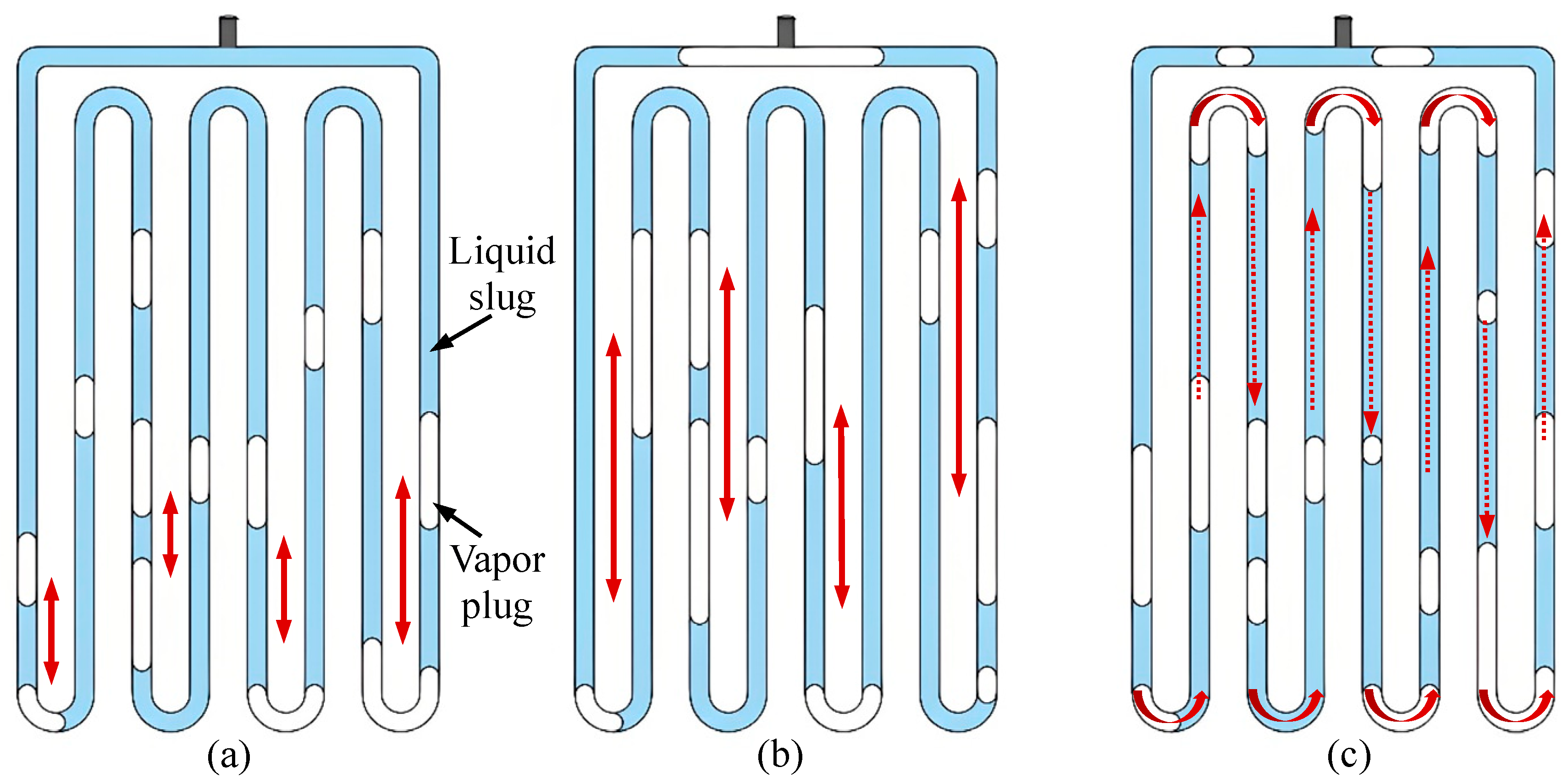

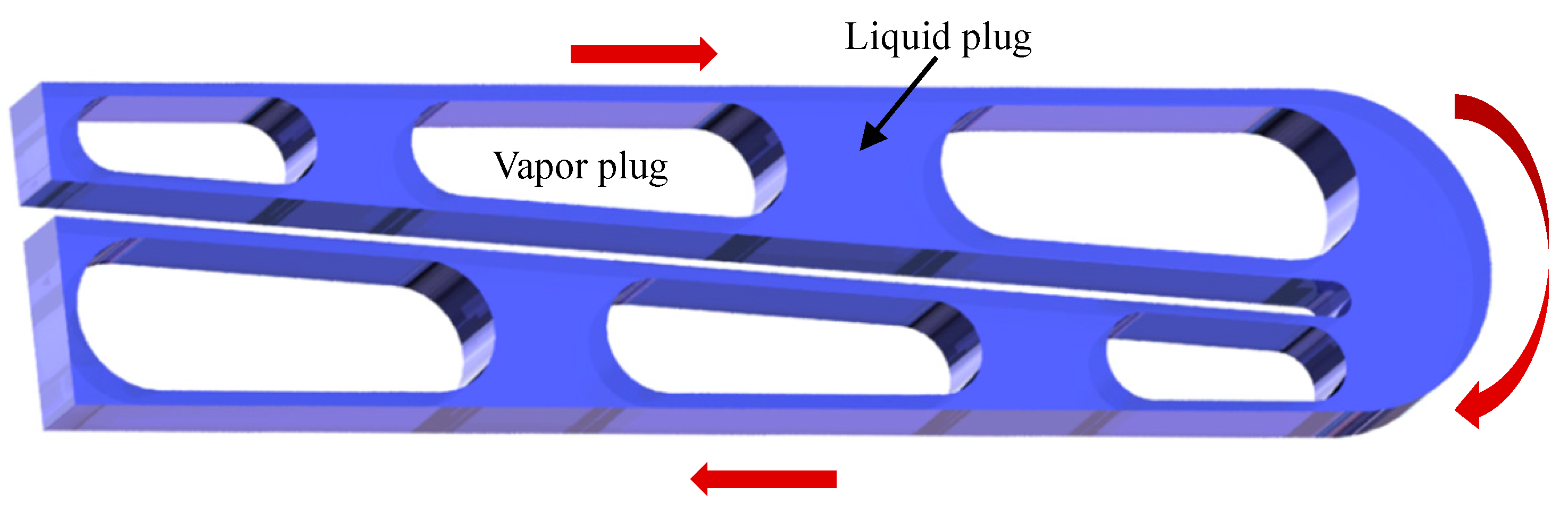

3.1. Flow Motion Patterns of Working Fluid in the MPHP

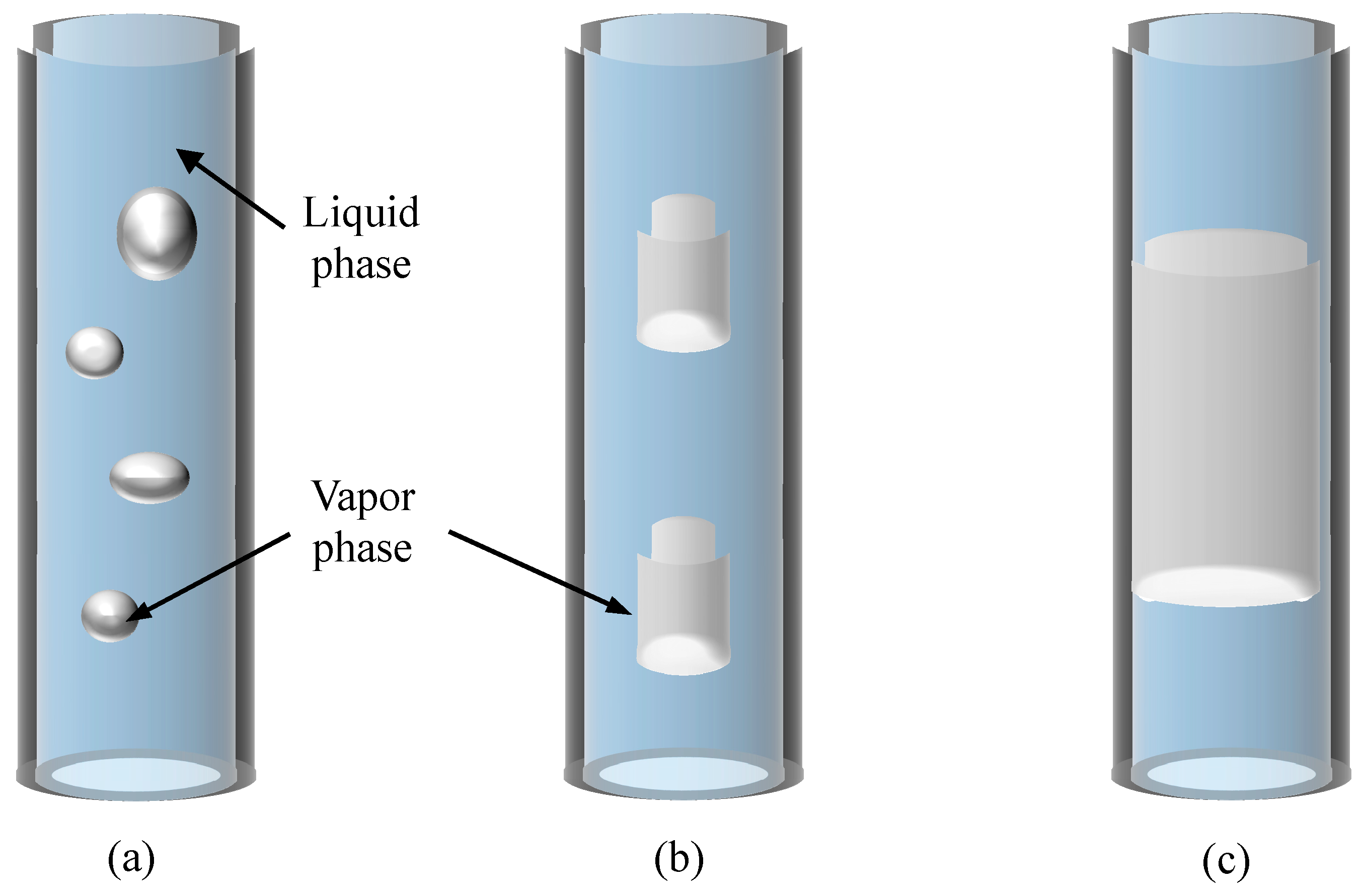

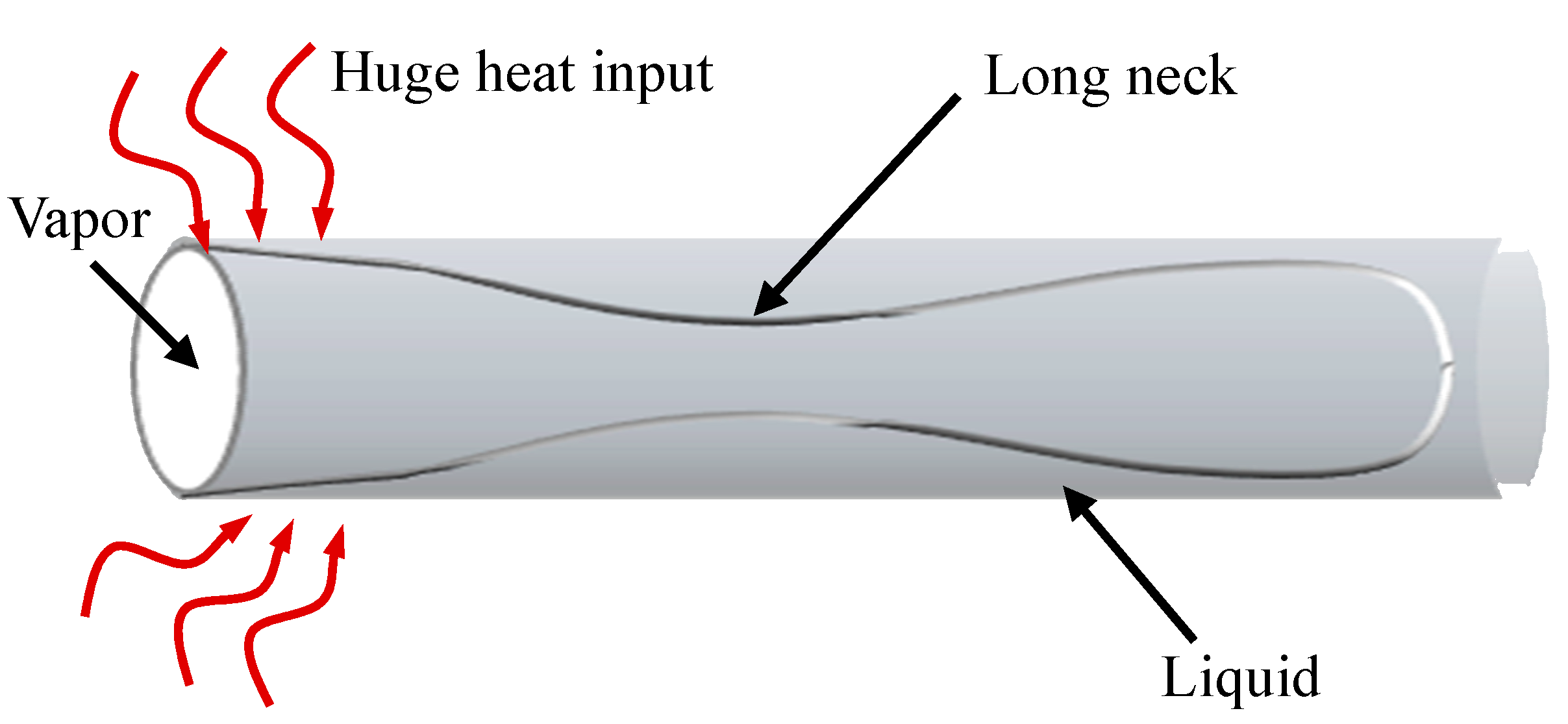

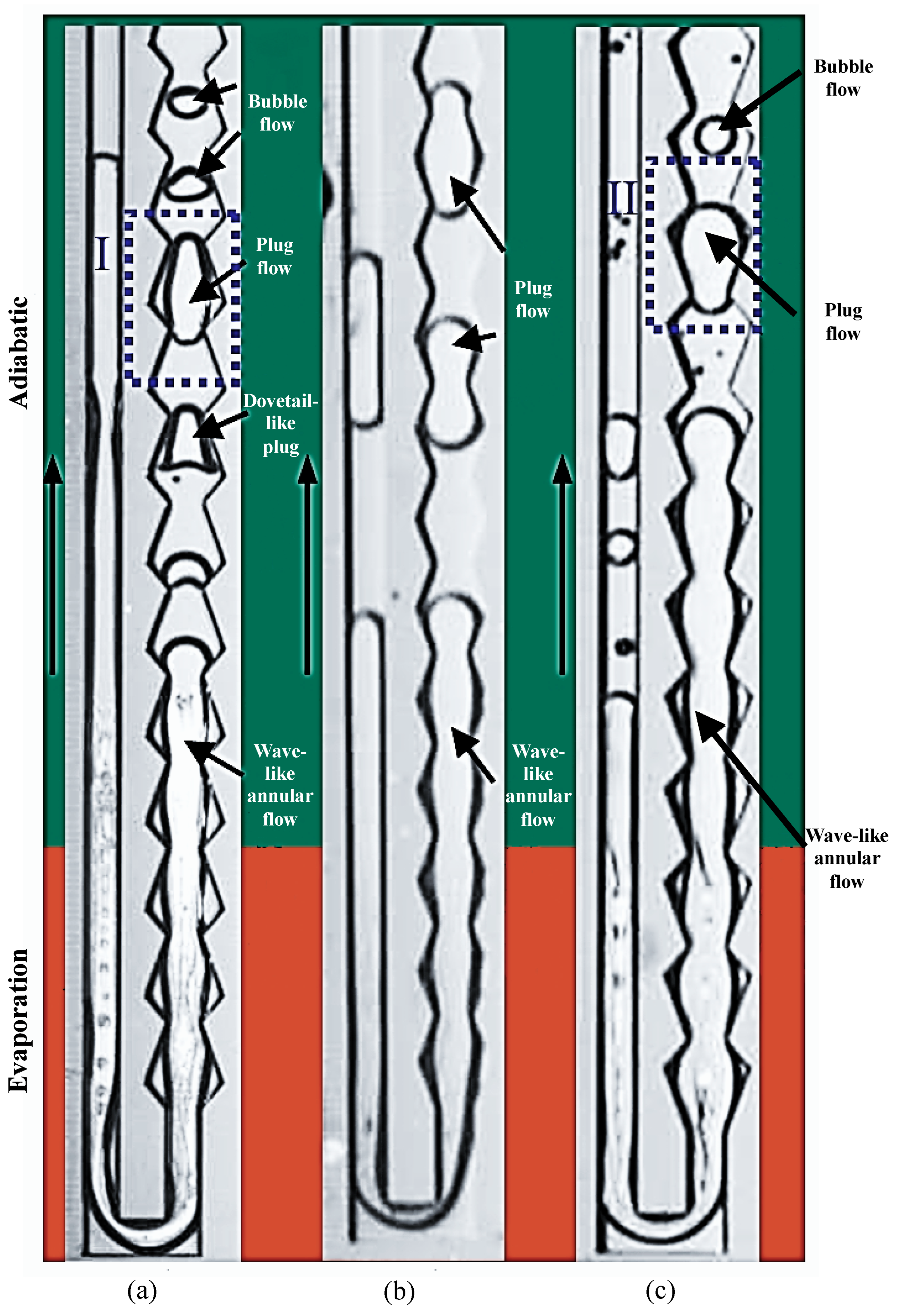

3.2. Flow Patterns and Their Evolution in MPHPs

4. Experimental Study on Heat Transfer Performance of the MPHP

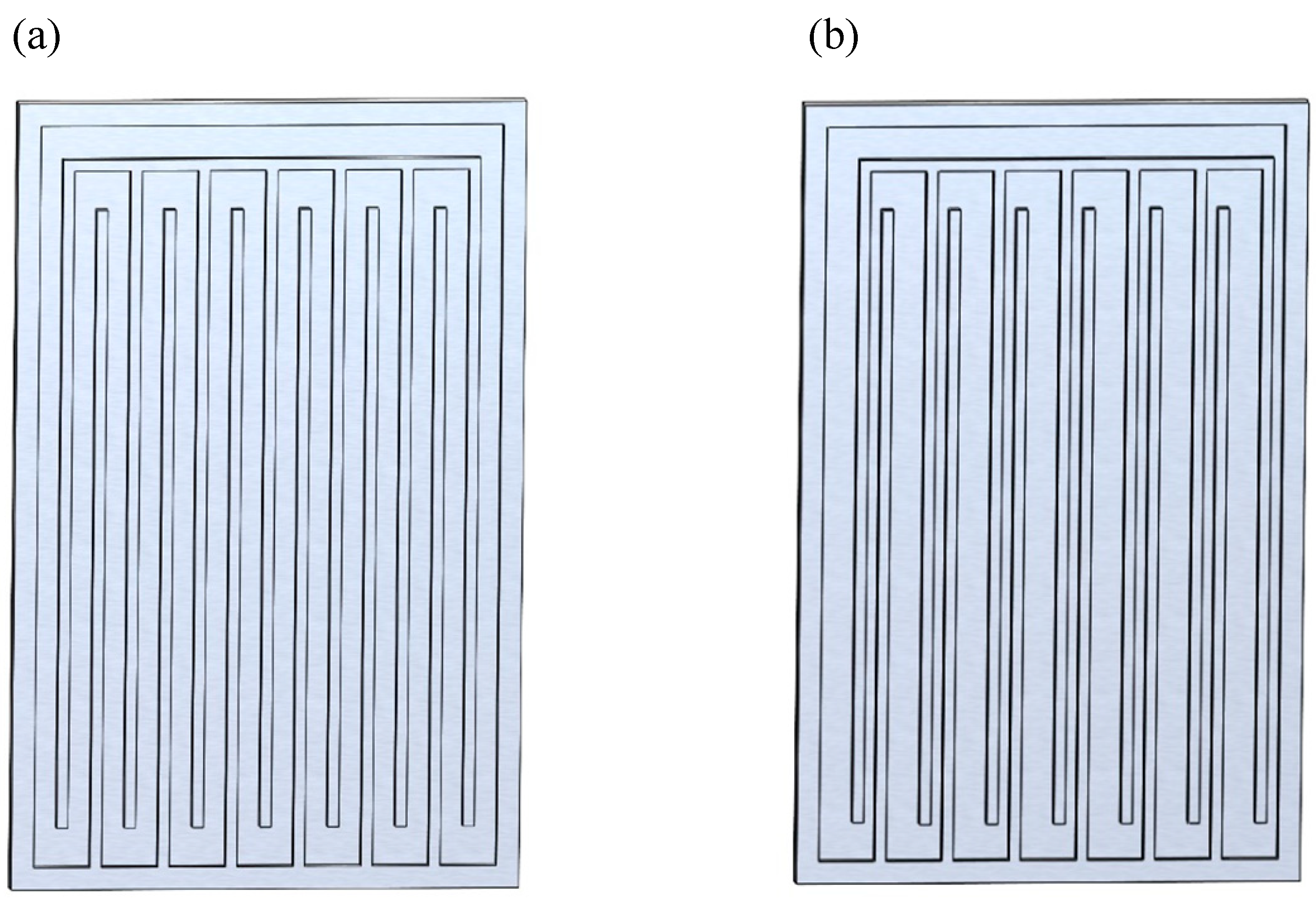

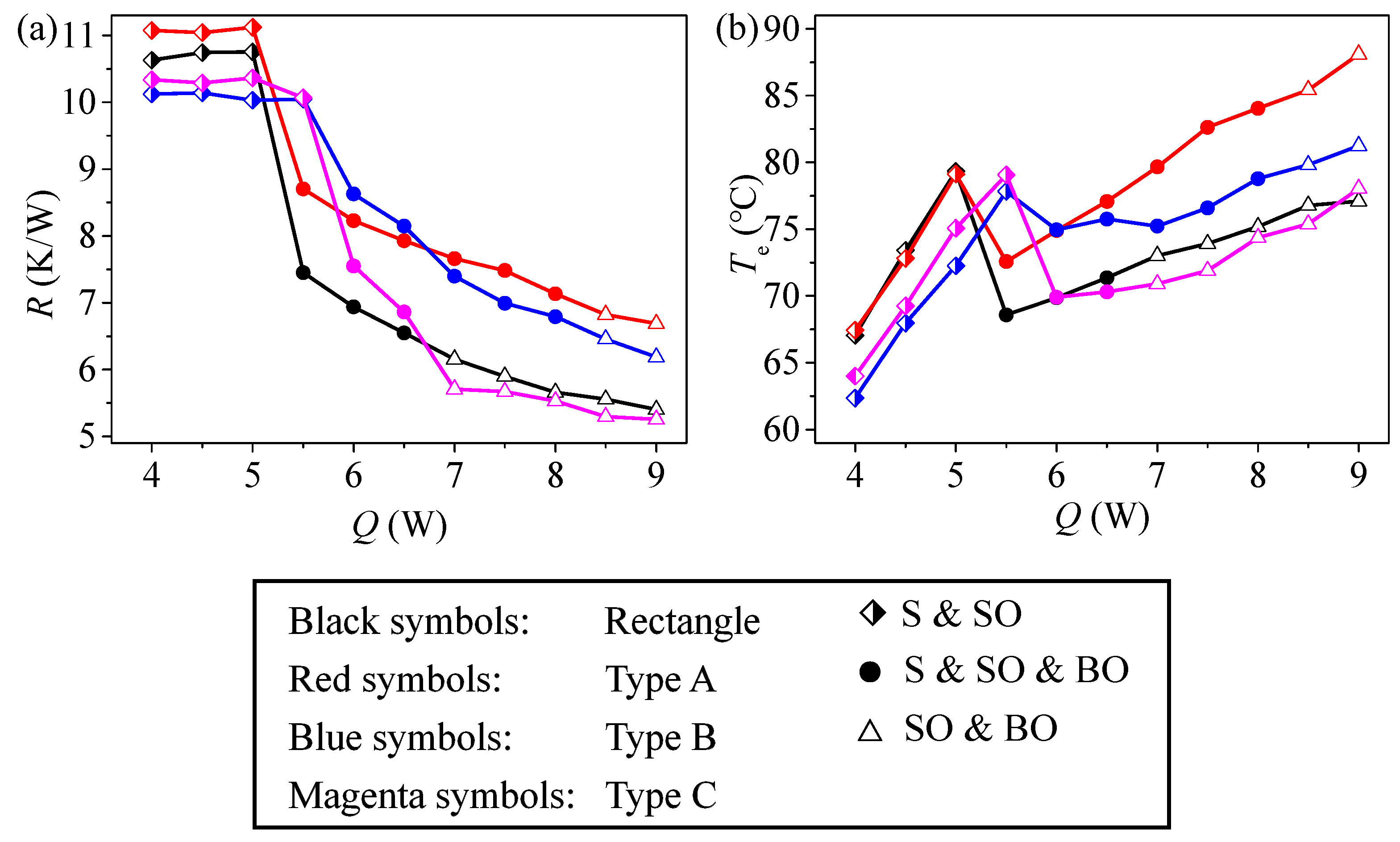

4.1. Influence of Channel Structure Parameters

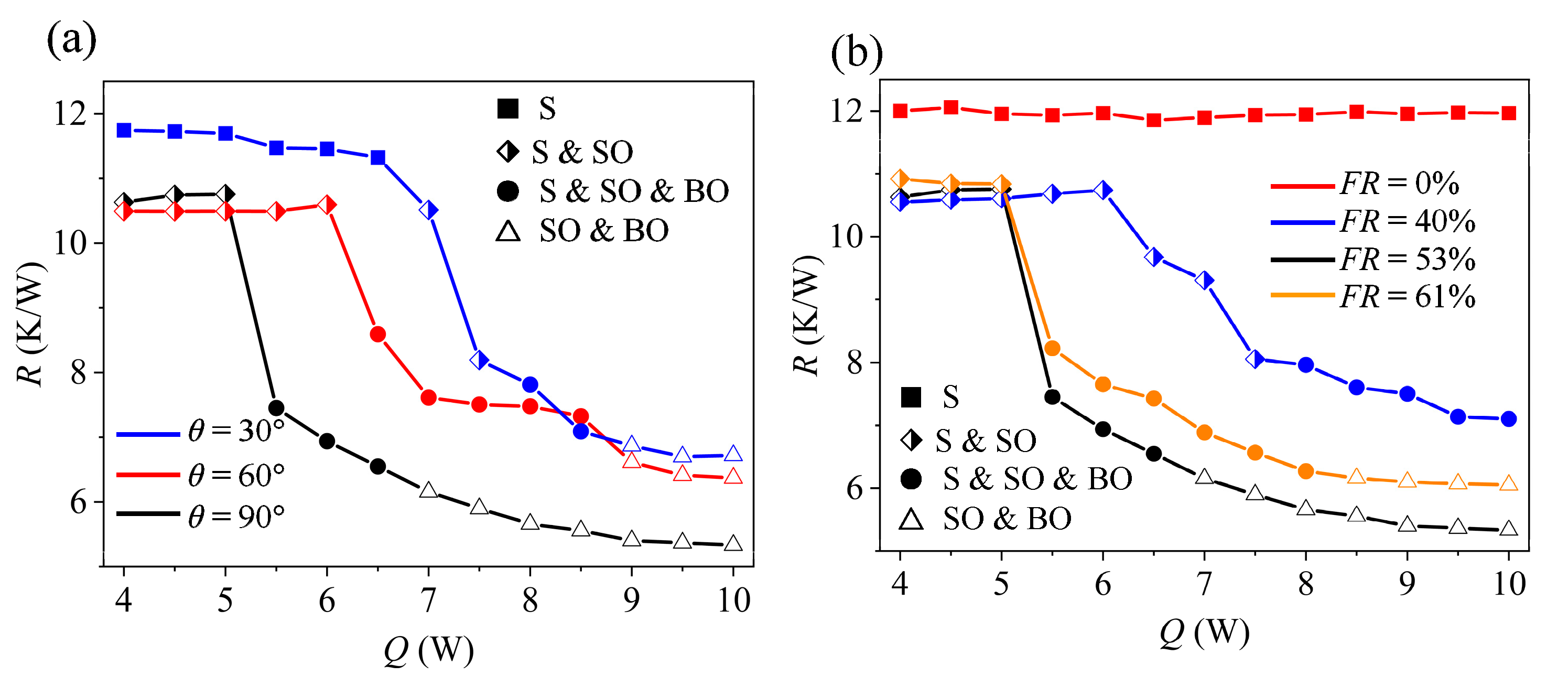

4.2. Effect of Inclination Angle (Gravity)

4.3. Effect of Fill Ratio

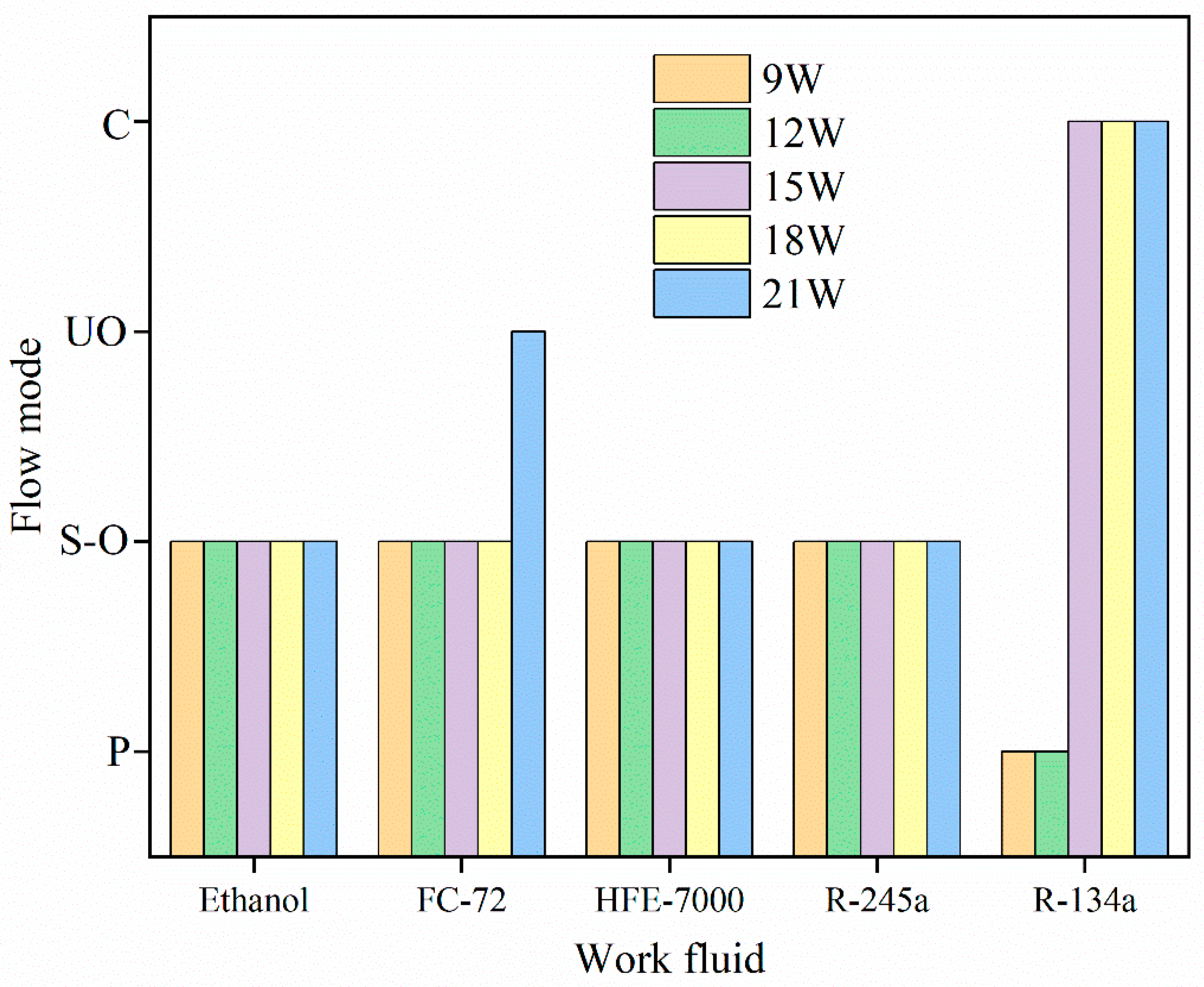

4.4. The Influence of the Working Fluid

4.5. Other Influencing Factors

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- High-speed camera technology is the most widely used visualization technique, but it requires either a metal-based/silicon-based plate-type MPHP or a specifically manufactured tubular MPHP made of transparent glass material.

- (2)

- The flow pattern inside the tube changes as the input power rises, starting as a bubble flow and progressing to a plug flow and annular flow. Additionally, the motion pattern of the working fluid inside the tube progressively changes from SO to LO to C.

- (3)

- The C may stop under the impact of variables, including filling ratio, working fluid parameters, and hydraulic diameter, resulting in sporadic S occurrences inside the pipe. The motion mode influences the flow pattern inside the pipe, and injection flow is visible in areas like the condensation zone.

- (4)

- Channel structure, inclination angle, working fluid physical characteristics, and fill ratio are some of the variables that affect the MPHP’s heat transfer performance. In particular, the MPHP with asymmetric channel configurations (such as alternating diameters) shows better heat transfer performance and less thermal resistance than symmetric channel structures. High (dP/dT)sat values, low viscosity, low latent heat, and low surface tension working fluids can efficiently promote C inside the tubes, improving the MPHP’s heat transfer efficiency. Furthermore, when placed vertically and running at a moderate fill ratio (40–70%), the MPHP demonstrates greater heat transmission characteristics.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MPHP | Micro pulsating heat pipe |

| SSPHP | Small-scale pulsating heat pipe |

| PHP | Pulsating heat pipe |

| FPPHP | Flat plate pulsating heat pipe |

| SO | Small oscillation |

| LO | Large oscillation |

| C | Circulation |

| S-O | Stable oscillation |

| BO | Bulk oscillation |

| S | Stop-over |

| P | Pulsing flow |

| UO | Unstable oscillating flow |

| LAOP | Large-amplitude oscillation phase |

| SAOP | Small-amplitude oscillation phase |

| CDC-FPMPHP | Flat-plate micro pulsating heat pipe with asymmetric converging-diverging channels |

| UC-FPMPHP | Flat-plate micro pulsating heat pipe with uniform rectangular channels |

| MPA | Micro-post array |

| FR | Fill ratio |

References

- He, Z.Q.; Yan, Y.F.; Zhang, Z.E. Thermal management and temperature uniformity enhancement of electronic devices by micro heat sinks: A review. Energy 2021, 216, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.S.; Wang, T.Y.; Gao, H.K.; Li, Y.; Dong, H.L.; Hu, W.P. Organic polarized light-emitting transistors. Adv. Mater 2023, 35, 2301955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, J.H.; Li, X.C.; Liang, T.; Rao, T.Y.; Zheng, Z.Y.; Yao, Y.M.; Xu, J.B.; Sun, R.; Li, L.J. Thermally conductive and self-healable liquid metal elastomer composites based on poly(ionic liquid)s. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2025, 194, 108922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, B.; Deka, H.; Sharma, P.; Barik, D.; Medhi, B.J.; Bora, B.J.; Paramasivam, P.; Agbulut, Ü. Maximizing efficiency: Exploring the crucial role of ducts in air-cooled lithium-ion battery thermal management. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2025, 150, 3121–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharaibeh, A.R.; Rangarajan, S.; Soud, Q.S.; Al-Zubi, O.; Manaserh, Y.; Sammakia, B. Thermal challenges in heterogeneous packaging: Experimental and machine learning approaches to liquid cooling. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 260, 125081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Lu, Y.W.; Kandlikar, S.G. Effects of nanowire height on pool boiling performance of water on silicon chips. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2011, 50, 2084–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plawsky, J.L.; Fedorov, A.G.; Garimella, S.V.; Ma, H.B.; Maroo, S.C.; Chen, L.; Nam, Y. Nano- and microstructures for thin-film evaporation-a review. Nanoscale Microscale Thermophys. Eng. 2014, 18, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Q.; Liu, W.D.; Lyu, W.; Yin, L.C.; Yue, Y.C.; Gao, H.; Li, M.; Shi, X.L.; Liu, Q.F.; Wang, N.; et al. Alignment of edge dislocations—The reason lying behind composition inhomogeneity induced low thermal conductivity. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 9775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.P.; Zhang, T.S.; Gao, Q.; Lv, J.W.; Chen, H.B.; Huang, H.Z. Thermal management enhancement of electronic chips based on novel technologies. Energy 2025, 316, 134575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.R.; Cao, Q.; Qin, B.C.; Zhao, L.D. Progress and challenges for thermoelectric cooling: From materials and devices to manifold applications. Mater. Lab. 2024, 3, 230032. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, J.; Wu, H.Y.; Wang, Q. Experimental investigation of silicon-based micro-pulsating heat pipe for cooling electronics. Nanoscale Microscale Thermophys. Eng. 2012, 16, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, N.; Miyazaki, Y.; Yasuda, S.; Ogawa, H. Thermal performance and flexibility evaluation of metallic micro oscillating heat pipe for thermal strap. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 197, 117342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.J.; Kawaji, M.; Futamata, R. Microgravity performance of micro pulsating heat pipes. Microgravity Sci. Technol. 2005, 16, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Z.; Liu, W.S. An engineering roadmap for the thermoelectric interface materials. J. Mater. 2024, 10, 748–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.P.; Hu, Y.X.; Zheng, S.B.; Wu, T.T.; Liu, K.Z.; Zhu, M.H.; Huang, J. Recent advances in visualization of pulsating heat pipes: A review. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 221, 119867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.H.; Su, L.M.; Jiang, J.; Deng, W.Y.; Zhao, D. A review of working fluids and flow state effects on thermal performance of micro-channel oscillating heat pipe for aerospace heat dissipation. Aerospace 2023, 10, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Wang, G.D.; Quan, X.J. Recent work on boiling and condensation in microchannels. J. Heat Transf. 2009, 131, 043211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandlikar, S.G. History, advances, and challenges in liquid flow and flow boiling heat transfer in microchannels: A Critical Review. J. Heat Transf. 2012, 134, 034001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattani, L.; Vocale, P.; Bozzoli, F.; Malavasi, M.; Pagliarini, L.; Iwata, N. Global and local performances of a tubular micro-pulsating heat pipe: Experimental investigation. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 58, 2009–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, N.; Bozzoli, F.; Pagliarini, L.; Cattani, L.; Vocale, P.; Malavasi, M.; Rainieri, S. Characterization of thermal behavior of a micro pulsating heat pipe by local heat transfer investigation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 196, 123203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemadri, V.A.; Gupta, A.; Khandekar, S. Thermal radiators with embedded pulsating heat pipes: Infra-red thermography and simulations. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2011, 31, 1332–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.B.; Kim, H.; Sung, J. Investigation of thermal enhancement factor in micro pulsating heat exchanger using LIF visualization technique. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 159, 120121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S.; Kim, S.J. Experimental investigation on the thermodynamic state of vapor plugs in pulsating heat pipes. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 134, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Li, Y. Experimental research on heat transfer of pulsating heat pipe. J. Therm. Sci. 2008, 17, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, X.D.; Shen, C.Q.; Chen, Y.P. Experimental study on vapor-liquid two-phase flow and heat transfer characteristics in micro pulsating heat pipe. J. Eng. Thermophys 2018, 39, 1285–1290. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, D.S.; Lee, J.S.; Ahn, J.H.; Kim, D.W.; Kim, Y.C. Flow patterns and heat transfer characteristics of flat plate pulsating heat pipes with various asymmetric and aspect ratios of the channels. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 114, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.D.; Xu, L.Y.; Wang, C.; Han, X.T. Experimental study on thermo-hydrodynamic characteristics in a micro oscillating heat pipe. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2019, 109, 109871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. Study of Thermally-Driven Vapor-Liquid Two-Phase Flow and Heat Transfer Mechanisms in Micro Pulsating Heat Pipe. Ph.D. Thesis, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, W.; Ma, T.Z. Experimental investigation on flow and heat transfer of pulsating heat pipe. J. Eng. Thermophys. 2002, 23, 596–598. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, J.; Wu, H.; Cheng, P. Start-up, heat transfer and flow characteristics of silicon-based micro pulsating heat pipes. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2012, 55, 6109–6120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, S.J. Experimental investigation on working fluid selection in a micro pulsating heat pipe. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 205, 112462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Qu, J.; Yuan, J.P.; Wang, Q. Operational characteristics of an MEMS-based micro oscillating heat pipe. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 124, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Wu, H.Y. Flow visualization of silicon-based micro pulsating heat pipes. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2010, 53, 984–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Wu, H.Y. Thermal performance of micro pulsating heat pipe. CIESC J. 2011, 62, 3046–3052. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Qu, J.; Yuan, J.P.; Wang, H. Start-up characteristics of MEMS-based micro oscillating heat pipe with and without bubble nucleation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 122, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Qu, J.; Yuan, J.P. Heat transfer performance comparison of silicon-based micro oscillating heat pipes with and without expanding channels. CIESC J. 2017, 68, 1803–1810. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.B.; Song, H.W.; Sung, J. Flow behavior of rapid thermal oscillation inside an asymmetric micro pulsating heat exchanger. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 120, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Hsu, W.L.; Magnini, M.; Mason, L.R.; Ho, Y.L.; Matar, O.K.; Daiguji, H. Single-bubble dynamics in nanopores: Transition between homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation. Phys. Rev. Res. 2020, 2, 043400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, A.; Kim, S.J. Understanding of the thermo-hydrodynamic coupling in a micro pulsating heat pipe. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 127, 1004–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Wu, H.Y.; Tang, H.M. Flow visualization of micro/mini pulsating heat pipes. J. Aerosp. Power 2009, 24, 766–771. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.X.; Li, J.M. Numerical simulation of gas-liquid interface evolution for flow and condensation in square microchannel. CIESC J. 2018, 69, 2851–2859. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, X.J.; Cheng, P.; Wu, H.Y. Transition from annular flow to plug/slug flow in condensation of steam in microchannels. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2008, 51, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, H.; Han, X.T.; Liu, X.D. Thermo-hydrodynamic characteristics of a novel flat-plate micro pulsating heat pipe with asymmetric converging-diverging channels. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 152, 107282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.J. Experimental investigations of heat transfer mechanisms of a pulsating heat pipe. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 181, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Kim, S.J. Effect of channel geometry on the operating limit of micro pulsating heat pipes. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2017, 107, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Kim, S.J. Effect of reentrant cavities on the thermal performance of a pulsating heat pipe. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 133, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Kim, S.J. Effects of the micro-post array on the maximum allowable input power for a micro pulsating heat pipe. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 193, 122898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, S.; Kumar, R.; Kumar Das, A. Evaluation of thermo-fluidic performance of micro pulsating heat pipe with and without evaporator side surface structures. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 249, 123470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, G.H.; Kim, S.J. Experimental investigation on the thermal performance of a micro pulsating heat pipe with a dual-diameter channel. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2015, 89, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.S.; Cheng, Y.C.; Liu, M.C.; Shyu, J.C. Micro pulsating heat pipes with alternate microchannel widths. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2015, 83, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Kim, S.J. Effect of a channel layout on the thermal performance of a flat plate micro pulsating heat pipe under the local heating condition. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 137, 1232–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.P.; Bai, R.X.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Han, X.T.; Liu, X.D. Investigation of thermo-hydrodynamic characteristics in micro-oscillating heat pipe by alternatively-arranged ratchet microchannels. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 222, 125134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, S.J. Experimental investigation on the effect of the condenser length on the thermal performance of a micro pulsating heat pipe. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 130, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Joo, Y.; Kim, S.J. Effects of the number of turns and the inclination angle on the operating limit of micro pulsating heat pipes. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 124, 1172–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S.; Kim, S.J. Comparison of the thermal performances and flow characteristics between closed-loop and closed-end micro pulsating heat pipes. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2016, 95, 890–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, X.; Zheng, H.; Xu, X.; Chen, G. Review of the development of pulsating heat pipe for heat dissipation. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2016, 59, 692–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, E.R.; Reddy, G.V.G. Effect of filling ratio on thermal performance of closed loop pulsating heat pipe. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 22229–22236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faghri, A. Review and advances in heat pipe science and technology. J. Heat Transf. 2012, 134, 123001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandekar, S.; Silwal, V.; Bhatnagar, A.; Sharma, P. Global effectiveness of pulsating heat pipe heat exchangers: Modeling and experiments. Heat Pipe Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2010, 1, 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, T.; Li, X.; Wang, S. Heat transfer enhancement of micro oscillating heat pipes with self-rewetting fluid. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2014, 70, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahani, K.; Mohammadi, M.; Shafii, M.B.; Shiee, Z. Promising technology for electronic cooling: Nanofluidic micro pulsating heat pipes. J. Electron. Packag. 2013, 135, 021005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Cho, H.; Jung, S.Y. Improvements in performance and durability through surface modification of aluminum micro-pulsating heat pipe using water as working fluid. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 214, 124445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, A.; Kim, S.J. Experimental and theoretical studies on oscillation frequencies of liquid slugs in micro pulsating heat pipes. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 181, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, A.; Kim, S.J. Characteristics of oscillating flow in a micro pulsating heat pipe: Fundamental-mode oscillation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2017, 109, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamijima, C.; Yoshimoto, Y.; Abe, Y.; Takagi, S.; Kinefuchi, I. Relating the thermal properties of a micro pulsating heat pipe to the internal flow characteristics via experiments, image recognition of flow patterns and heat transfer simulations. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 163, 120415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; Tian, H.; Xu, W.; Guo, H.; Wang, C.; Gu, J.; Cao, Y. Experimental Research Progress on Gas–Liquid Flow and Heat Transfer Characteristics in Micro Pulsating Heat Pipes. Micromachines 2026, 17, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010037

Chen J, Tian H, Xu W, Guo H, Wang C, Gu J, Cao Y. Experimental Research Progress on Gas–Liquid Flow and Heat Transfer Characteristics in Micro Pulsating Heat Pipes. Micromachines. 2026; 17(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Jun, Hao Tian, Wanli Xu, Huangdong Guo, Chao Wang, Jincheng Gu, and Yichao Cao. 2026. "Experimental Research Progress on Gas–Liquid Flow and Heat Transfer Characteristics in Micro Pulsating Heat Pipes" Micromachines 17, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010037

APA StyleChen, J., Tian, H., Xu, W., Guo, H., Wang, C., Gu, J., & Cao, Y. (2026). Experimental Research Progress on Gas–Liquid Flow and Heat Transfer Characteristics in Micro Pulsating Heat Pipes. Micromachines, 17(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010037