Snake Venom Disintegrins and Cell Migration

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Integrins and Cell Migration

3. Angiogenesis

4. Disintegrins from Snake Venoms

5. Effects of Disintegrins on Leukocyte Migration

6. Effects of Disintegrins on Endothelial Cell Migration and Angiogenesis

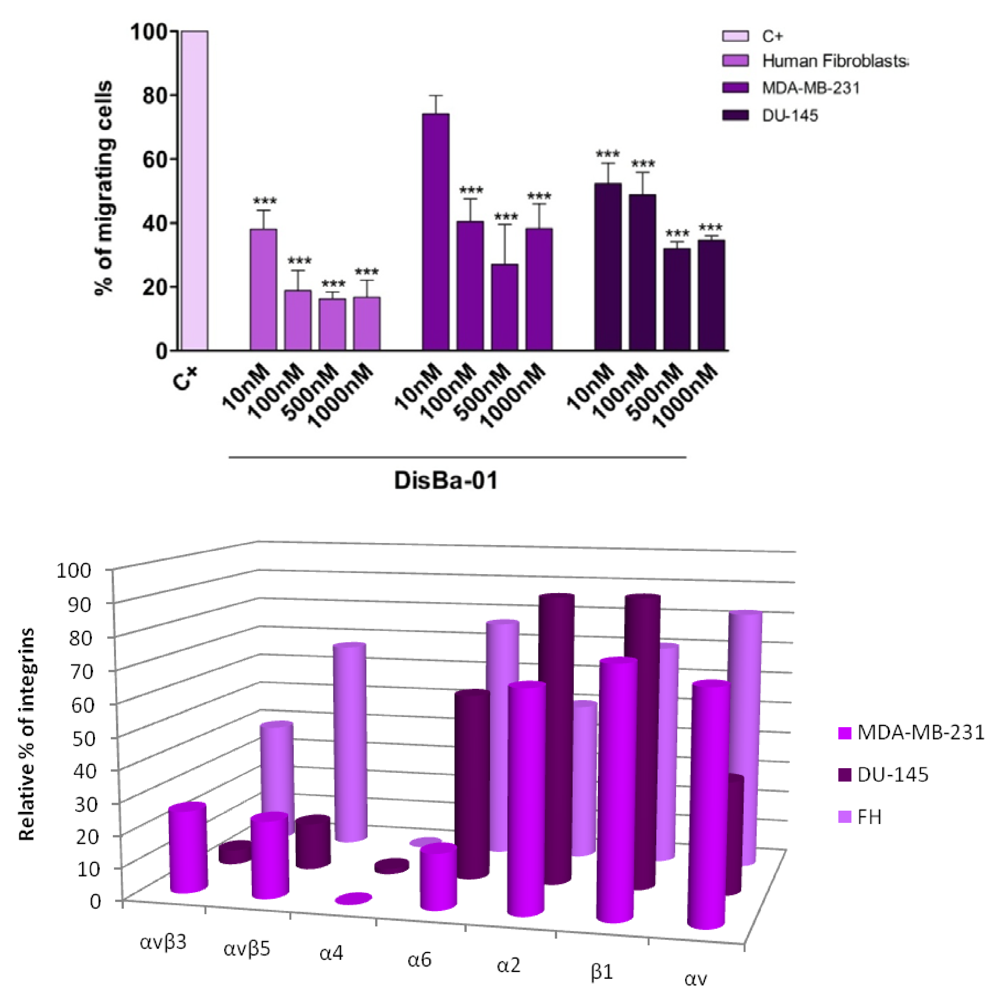

7. Effects of Disintegrins on Tumor Cell Migration

| Disintegrin | Structure | Adhesive motif | Preferred integrin | Cognate ligand | Relevant inhibitory activity (conc.*) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legend: Vn, vitronectin; Fn, fibronectin; Fg, fibrinogen; TN, tenascin; ICAM-1, intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1; VCAM, vascular cell adhesion molecule. * Effective inhibitory concentration; ** in vivo assays. | ||||||

| salmosin 2 | monomeric medium | RGD | αvβ3 | Vn | angiogenesis ** (5 μg) | [65] |

| saxatilin | monomeric medium | RGD | αvβ3 | Vn | angiogenesis (100 nM) | [54] |

| jarastatin | monomeric medium | RGD | αvβ3, α5β1, αMβ2 | Vn, Fn, ICAM-1 | melanoma lung metastasis ** (1 μM) | [66] |

| flavoridin | monomeric medium | RGD | α5β1 | Fn | melanoma lung metastasis ** (1 μM) | [66] |

| kistrin | monomeric medium | RGD | αvβ3 | Vn | melanoma lung metastasis **( 1 μM) | [66] |

| colombistatin | monomeric medium | RGD | nd | Fn | tumor cell migration (IC50 = 1.8 μM) | [67] |

| trigramin | monomeric medium | RGD | αvβ3 | Vn | bone metastasis **(100 μg/ml) | [68] |

| DisBa-01 | monomeric medium | RGD | αvβ3 | Vn | melanoma metastasis **(2 mg/Kg) | [33] |

| eristostatin | monomeric short | RGD | αIIbβ3 | Fg | melanoma metastasis (25 μg) | [69] |

| echistatin | monomeric short | RGD | αvβ3 | Vn | osteoclast migration (10 nM) | [70] |

| triflavin | monomeric short | RGD | αvβ3 | Vn | angiogenesis **(0.1–0.4 μM) | [48] |

| contortrostatin | Homodimeric | RGD | α5β1, αvβ5 | Fn | tumor angiogenesis **(60 μg/day) | [71] |

| alternagin-C | monomeric D/C | ECD | α2β1 | collagen I | angiogenesis **(1 μM) | [63] |

| leberagin-C | monomeric D/C | ECD | αvβ3, α5β1, αvβ6 | Vn, Fn | melanoma cell adhesion (100 nM) | [72] |

| acurhagin-C | monomeric D/C | ECD | αvβ3 | Vn | angiogenesis **(0.4 μM) | [61] |

| VLO5 | heterodimeric | VGD, MLD | α9β1 | TN, VCAM | glioblastoma growth (100 μg/ml) | [73] |

| obtustatin | monomeric short | KTS | α1β1 | collagen IV | angiogenesis **(0.4 μg/μl) | [74] |

| viperistatin | monomeric short | KTS | α1β1 | collagen IV | melanoma cell transmigration (1–4 μM) | [75] |

| lebestatin | monomeric short | KTS | α1β1 | collagen IV | angiogenesis **(0.1–0.5 μg/embryo) | [59] |

8. ADAMs and Cell Migration

9. Concluding Remarks

Acknowledgements

References

- Barkan, D.; Green, J.E.; Chambers, A.F. Extracellular matrix: A gatekeeper in the transition from dormancy to metastatic growth. Eur. J. Canc. 2010, 46, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Fokas, E.; Engenhart-Cabillic, R.; Daniilidis, K.; Rose, F.; An, H.X. Metastasis: The seed and soil theory gains identity. Canc. Metastasis Rev. 2007, 26, 705–715. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, J.A.; Pollard, J.W. Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat. Rev. Canc. 2009, 9, 239–252. [Google Scholar]

- Desgrosellier, J.S.; Cheresh, D.A. Integrins in cancer: Biological implications and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. 2010, 10, 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Miranti, C.K.; Brugge, J.S. Sensing the environment: A historical perspective on integrin signal transduction. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002, 4, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, F.; Heisenberg, C.P. Trafficking and cell migration. Traffic 2009, 10, 811–818. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, T.R.; Peeper, D.S. Metastasis mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1796, 293–308. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, J.D.; Cheresh, D.A. Role of integrins in cell invasion and migration. Nat. Rev. Canc. 2002, 2, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Rathinam, R.; Alahari, S.K. Important role of integrins in the cancer biology. Canc. Metastasis Rev. 2010, 29, 223–237. [Google Scholar]

- Sahai, E. Mechanisms of cancer cell invasion. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2005, 15, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, S.A.; Lomax-Browne, H.J.; Carter, T.M.; Kinch, C.E.; Hall, D.M. Molecular interactions in cancer cell metastasis. Acta Histochem. 2010, 112, 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, J. Angiogenesis: An organizing principle for drug discovery? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007, 6, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.T.; Huang, C.J.; Wu, M.T.; Yang, S.F.; Su, Y.C.; Chai, C.Y. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha is associated with risk of aggressive behavior and tumor angiogenesis in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 35, 207–213. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, M.J.; Claesson-Welsh, L. FGF and VEGF function in angiogenesis: Signalling pathways, biological responses and therapeutic inhibition. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2001, 22, 201–207. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, A.S.; Lee, J.; Ferrara, N. Targeting the tumour vasculature: Insights from physiological angiogenesis. Nat. Rev. Canc. 2010, 10, 505–514. [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly, M.S.; Boehm, T.; Shing, Y.; Fukai, N.; Vasios, G.; Lane, W.S.; Flynn, E.; Birkhead, J.R.; Olsen, B.R.; Folkman, J. Endostatin: An endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cell 1997, 88, 277–285. [Google Scholar]

- Zetter, B.R. Angiogenesis and tumor metastasis. Annu. Rev. Med. 1998, 49, 407–424. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Z.; Kumar, R.; Yang, X.; Fidler, I.J. Macrophage-derived metalloelastase is responsible for the generation of angiostatin in Lewis lung carcinoma. Cell 1997, 88, 801–810. [Google Scholar]

- Francavilla, C.; Maddaluno, L.; Cavallaro, U. The functional role of cell adhesion molecules in tumor angiogenesis. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2009, 19, 298–309. [Google Scholar]

- Turkbey, B.; Kobayashi, H.; Ogawa, M.; Bernardo, M.; Choyke, P.L. Imaging of tumor angiogenesis: Functional or targeted? Am. J. Roentgenol. 2009, 193, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.W.; Serrano, S.M. Insights into and speculations about snake venom metalloproteinase (SVMP) synthesis, folding and disulfide bond formation and their contribution to venom complexity. FEBS. J. 2008, 275, 3016–3030. [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnason, J.B.; Fox, J.W. Snake venom metalloendopeptidases: Reprolysins. Meth. Enzymol. 1995, 248, 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J.W.; Serrano, S.M. Structural considerations of the snake venom metalloproteinases, key members of the M12 reprolysin family of metalloproteinases. Toxicon 2005, 45, 969–985. [Google Scholar]

- Calvete, J.J.; Domont, G.B.; Padron, G. Meeting report MPSA 2007. J. Proteomics 2008, 71, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, O.H.; Selistre-de-Araujo, H.S. Snake venom metalloproteases—Structure and function of catalytic and disintegrin domains. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2006, 142, 328–346. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, H.H.; Goh, K.S.; Davamani, F.; Wu, P.L.; Huang, Y.W.; Jeyakanthan, J.; Wu, W.G.; Chen, C.J. Structures of two elapid snake venom metalloproteases with distinct activities highlight the disulfide patterns in the D domain of ADAMalysin family proteins. J. Struct. Biol. 2010, 169, 294–303. [Google Scholar]

- Takeda, S.; Igarashi, T.; Mori, H.; Araki, S. Crystal structures of VAP1 reveal ADAMs' MDC domain architecture and its unique C-shaped scaffold. Embo. J. 2006, 25, 2388–2396. [Google Scholar]

- Tanjoni, I.; Evangelista, K.; Della-Casa, M.S.; Butera, D.; Magalhaes, G.S.; Baldo, C.; Clissa, P.B.; Fernandes, I.; Eble, J.; Moura-da-Silva, A.M. Different regions of the class P-III snake venom metalloproteinase jararhagin are involved in binding to alpha2beta1 integrin and collagen. Toxicon 2010, 55, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar]

- Menezes, M.C.; Paes Leme, A.F.; Melo, R.L.; Silva, C.A.; Della Casa, M.; Bruni, F.M.; Lima, C.; Lopes-Ferreira, M.; Camargo, A.C.; Fox, J.W.; Serrano, S.M. Activation of leukocyte rolling by the cysteine-rich domain and the hyper-variable region of HF3, a snake venom hemorrhagic metalloproteinase. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 3915–3921. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, S.M.; Kim, J.; Wang, D.; Dragulev, B.; Shannon, J.D.; Mann, H.H.; Veit, G.; Wagener, R.; Koch, M.; Fox, J.W. The cysteine-rich domain of snake venom metalloproteinases is a ligand for von Willebrand factor A domains: Role in substrate targeting. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 39746–39756. [Google Scholar]

- Normand, P. Personal Communication. 2010. Peter Mac Callum Cancer Center, Melbourne, VIC. [Google Scholar]

- Minea, R.; Swenson, S.; Costa, F.; Chen, T.C.; Markland, F.S. Development of a novel recombinant disintegrin, contortrostatin, as an effective anti-tumor and anti-angiogenic agent. Pathophysiol. Haemost. Thromb. 2005, 34, 177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, O.H.; Kauskot, A.; Cominetti, M.R.; Bechyne, I.; Salla Pontes, C.L.; Chareyre, F.; Manent, J.; Vassy, R.; Giovannini, M.; Legrand, C.; Selistre-de-Araujo, H.S.; Crepin, M.; Bonnefoy, A. A novel alpha(v)beta (3)-blocking disintegrin containing the RGD motive, DisBa-01, inhibits bFGF-induced angiogenesis and melanoma metastasis. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2008, 25, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ley, K.; Laudanna, C.; Cybulsky, M.I.; Nourshargh, S. Getting to the site of inflammation: The leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 678–689. [Google Scholar]

- Lindbom, L.; Werr, J. Integrin-dependent neutrophil migration in extravascular tissue. Semin. Immunol. 2002, 14, 115–121. [Google Scholar]

- Saldanha-Gama, R.F.; Moraes, J.A.; Mariano-Oliveira, A.; Coelho, A.L.; Walsh, E.M.; Marcinkiewicz, C.; Barja-Fidalgo, C. alpha(9)beta(1) integrin engagement inhibits neutrophil spontaneous apoptosis: Involvement of Bcl-2 family members. Biochim. Biophys Acta 2010, 1803, 848–857. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M.A.; Solomkin, J.S. Integrin-mediated signaling in human neutrophil functioning. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1999, 65, 725–736. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, A.L.; de Freitas, M.S.; Oliveira-Carvalho, A.L.; Moura-Neto, V.; Zingali, R.B.; Barja-Fidalgo, C. Effects of jarastatin, a novel snake venom disintegrin, on neutrophil migration and actin cytoskeleton dynamics. Exp. Cell Res. 1999, 251, 379–387. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, A.L.; de Freitas, M.S.; Mariano-Oliveira, A.; Rapozo, D.C.; Pinto, L.F.; Niewiarowski, S.; Zingali, R.B.; Marcinkiewicz, C.; Barja-Fidalgo, C. RGD- and MLD-disintegrins, jarastatin and EC3, activate integrin-mediated signaling modulating the human neutrophils chemotaxis, apoptosis and IL-8 gene expression. Exp. Cell Res. 2004, 292, 371–384. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, A.L.; de Freitas, M.S.; Mariano-Oliveira, A.; Oliveira-Carvalho, A.L.; Zingali, R.B.; Barja-Fidalgo, C. Interaction of disintegrins with human neutrophils induces cytoskeleton reorganization, focal adhesion kinase activation, and extracellular-regulated kinase-2 nuclear translocation, interfering with the chemotactic function. FASEB. J. 2001, 15, 1643–1645. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.B.; Theakston, R.D.; Coelho, A.L.; Barja-Fidalgo, C.; Calvete, J.J.; Marcinkiewicz, C. Characterization of a monomeric disintegrin, ocellatusin, present in the venom of the Nigerian carpet viper, Echis ocellatus. FEBS Lett. 2002, 512, 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Barja-Fidalgo, C.; Coelho, A.L.; Saldanha-Gama, R.; Helal-Neto, E.; Mariano-Oliveira, A.; Freitas, M.S. Disintegrins: Integrin selective ligands which activate integrin-coupled signaling and modulate leukocyte functions. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2005, 38, 1513–1520. [Google Scholar]

- Calvete, J.J.; Moreno-Murciano, M.P.; Theakston, R.D.; Kisiel, D.G.; Marcinkiewicz, C. Snake venom disintegrins: Novel dimeric disintegrins and structural diversification by disulphide bond engineering. Biochem. J. 2003, 372, 725–734. [Google Scholar]

- Neto, E.H.; Coelho, A.L.; Sampaio, A.L.; Henriques, M.G.; Marcinkiewicz, C.; de Freitas, M.S.; Barja-Fidalgo, C. Activation of human T lymphocytes via integrin signaling induced by RGD-disintegrins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1773, 176–184. [Google Scholar]

- Mariano-Oliveira, A.; Coelho, A.L.; Terruggi, C.H.; Selistre-de-Araujo, H.S.; Barja-Fidalgo, C.; de Freitas, M.S. Alternagin-C, a nonRGD-disintegrin, induces neutrophil migration via integrin signaling. Eur. J. Biochem. 2003, 270, 4799–4808. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, D.H.; Iemma, M.R.; Ferreira, L.L.; Faria, J.P.; Oliva, M.L.; Zingali, R.B.; Niewiarowski, S.; Selistre-de-Araujo, H.S. The disintegrin-like domain of the snake venom metalloprotease alternagin inhibits alpha2beta1 integrin-mediated cell adhesion. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000, 384, 341–350. [Google Scholar]

- Clissa, P.B.; Lopes-Ferreira, M.; Della-Casa, M.S.; Farsky, S.H.; Moura-da-Silva, A.M. Importance of jararhagin disintegrin-like and cysteine-rich domains in the early events of local inflammatory response. Toxicon 2006, 47, 591–596. [Google Scholar]

- Sheu, J.R.; Yen, M.H.; Kan, Y.C.; Hung, W.C.; Chang, P.T.; Luk, H.N. Inhibition of angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo: comparison of the relative activities of triflavin, an Arg-Gly-Asp-containing peptide and anti-alpha(v)beta3 integrin monoclonal antibody. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1997, 1336, 445–454. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, C.H.; Peng, H.C.; Yang, R.S.; Huang, T.F. Rhodostomin, a snake venom disintegrin, inhibits angiogenesis elicited by basic fibroblast growth factor and suppresses tumor growth by a selective alpha(v)beta(3) blockade of endothelial cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001, 59, 1333–1342. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.; Nakada, M.T.; Arnold, C.; Shieh, K.Y.; Markland, F.S., Jr. Contortrostatin, a dimeric disintegrin from Agkistrodon contortrix contortrix, inhibits angiogenesis. Angiogenesis 1999, 3, 259–269. [Google Scholar]

- Markland, F.S.; Shieh, K.; Zhou, Q.; Golubkov, V.; Sherwin, R.P.; Richters, V.; Sposto, R.A. Novel snake venom disintegrin that inhibits human ovarian cancer dissemination and angiogenesis in an orthotopic nude mouse model. Haemostasis 2001, 31, 183–191. [Google Scholar]

- Swenson, S.; Costa, F.; Ernst, W.; Fujii, G.; Markland, F.S. Contortrostatin, a snake venom disintegrin with anti-angiogenic and anti-tumor activity. Pathophysiol. Haemost. Thromb 2005, 34, 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Minea, R.O.; Helchowski, C.M.; Zidovetzki, S.J.; Costa, F.K.; Swenson, S.D.; Markland, F.S., Jr. Vicrostatin—An anti-invasive multi-integrin targeting chimeric disintegrin with tumor anti-angiogenic and pro-apoptotic activities. PLoS One 2010, 5, 10929. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, Y.J.; Kim, D.S.; Jeon, O.H.; Kim, D.S. Saxatilin suppresses tumor-induced angiogenesis by regulating VEGF expression in NCI-H460 human lung cancer cells. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007, 40, 439–443. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, Y.D.; Cho, K.S.; Sun, S.A.; Sung, H.J.; Kwak, K.W.; Hong, S.Y.; Kim, D.S.; Chung, K.H. Suppressive effect and mechanism of saxatilin, a disintegrin from Korean snake (Gloydius saxatilis), in vascular smooth muscle cells. Toxicon 2008, 52, 474–480. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.; Paquette-Straub, C.; Sage, E.H.; Funk, S.E.; Patel, V.; Galileo, D.; McLane, M.A. Inhibition of melanoma cell motility by the snake venom disintegrin eristostatin. Toxicon 2007, 49, 899–908. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Murciano, M.P.; Monleon, D.; Calvete, J.J.; Celda, B.; Marcinkiewicz, C. Amino acid sequence and homology modeling of obtustatin, a novel non-RGD-containing short disintegrin isolated from the venom of Vipera lebetina obtusa. Protein Sci. 2003, 12, 366–371. [Google Scholar]

- Kisiel, D.G.; Calvete, J.J.; Katzhendler, J.; Fertala, A.; Lazarovici, P.; Marcinkiewicz, C. Structural determinants of the selectivity of KTS-disintegrins for the alpha1beta1 integrin. FEBS Lett. 2004, 577, 478–482. [Google Scholar]

- Olfa, K.Z.; Jose, L.; Salma, D.; Amine, B.; Najet, S.A.; Nicolas, A.; Maxime, L.; Raoudha, Z.; Kamel, M.; Jacques, M.; Jean-Marc, S.; Mohamed el, A.; Naziha, M. Lebestatin, a disintegrin from Macrovipera venom, inhibits integrin-mediated cell adhesion, migration and angiogenesis. Lab. Invest. 2005, 85, 1507–1516. [Google Scholar]

- Calvete, J.J.; Fox, J.W.; Agelan, A.; Niewiarowski, S.; Marcinkiewicz, C. The presence of the WGD motif in CC8 heterodimeric disintegrin increases its inhibitory effect on alphaII(b)beta3, alpha(v)beta3, and alpha5beta1 integrins. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 2014–2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.J. Acurhagin-C, an ECD disintegrin, inhibits integrin alphavbeta3-mediated human endothelial cell functions by inducing apoptosis via caspase-3 activation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 160, 1338–1351. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cominetti, M.R.; Terruggi, C.H.; Ramos, O.H.; Fox, J.W.; Mariano-Oliveira, A.; De Freitas, M.S.; Figueiredo, C.C.; Morandi, V.; Selistre-de-Araujo, H.S. Alternagin-C, a disintegrin-like protein, induces vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF) expression and endothelial cell proliferation in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 18247–18255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ramos, O.H.; Terruggi, C.H.; Ribeiro, J.U.; Cominetti, M.R.; Figueiredo, C.C.; Berard, M.; Crepin, M.; Morandi, V.; Selistre-de-Araujo, H.S. Modulation of in vitro and in vivo angiogenesis by alternagin-C, a disintegrin-like protein from Bothrops alternatus snake venom and by a peptide derived from its sequence. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007, 461, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, V.L.; Schmidt, E.E.; Koop, S.; MacDonald, I.C.; Grattan, M.; Khokha, R.; McLane, M.A.; Niewiarowski, S.; Chambers, A.F.; Groom, A.C. Effects of the disintegrin eristostatin on individual steps of hematogenous metastasis. Exp. Cell Res. 1995, 219, 571–578. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, I.C.; Chung, K.H.; Lee, S.J.; Yun, Y.; Moon, H.M.; Kim, D.S. Purification and molecular cloning of a platelet aggregation inhibitor from the snake (Agkistrodon halys brevicaudus) venom. Thromb. Res. 1998, 91, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva, I.B.; Coelho, R.M.; Barcellos, G.G.; Saldanha-Gama, R.; Wermelinger, L.S.; Marcinkiewicz, C.; Benedeta Zingali, R.; Barja-Fidalgo, C. Effect of RGD-disintegrins on melanoma cell growth and metastasis: Involvement of the actin cytoskeleton, FAK and c-Fos. Toxicon 2007, 50, 1053–1063. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, E.E.; Rodriguez-Acosta, A.; Palomar, R.; Lucena, S.E.; Bashir, S.; Soto, J.G.; Perez, J.C. Colombistatin: A disintegrin isolated from the venom of the South American snake (Bothrops colombiensis) that effectively inhibits platelet aggregation and SK-Mel-28 cell adhesion. Arch. Toxicol. 2009, 83, 271–279. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.S.; Tang, C.H.; Chuang, W.J.; Huang, T.H.; Peng, H.C.; Huang, T.F.; Fu, W.M. Inhibition of tumor formation by snake venom disintegrin. Toxicon 2005, 45, 661–669. [Google Scholar]

- Danen, E.H.; Marcinkiewicz, C.; Cornelissen, I.M.; van Kraats, A.A.; Pachter, J.A.; Ruiter, D.J.; Niewiarowski, S.; van Muijen, G.N. The disintegrin eristostatin interferes with integrin alpha 4 beta 1 function and with experimental metastasis of human melanoma cells. Exp. Cell Res. 1998, 238, 188–196. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, I.; Tanaka, H.; Rodan, G.A.; Duong, L.T. Echistatin inhibits the migration of murine prefusion osteoclasts and the formation of multinucleated osteoclast-like cells. Endocrinology 1998, 139, 5182–5193. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Lin, E.; Wang, Q.; Swenson, S.; Jadvar, H.; Groshen, S.; Ye, W.; Markland, F.S.; Pinski, J. The disintegrin contortrostatin in combination with docetaxel is a potent inhibitor of prostate cancer in vitro and in vivo. Prostate 2010, 70, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Limam, I.; Bazaa, A.; Srairi-Abid, N.; Taboubi, S.; Jebali, J.; Zouari-Kessentini, R.; Kallech-Ziri, O.; Mejdoub, H.; Hammami, A.; El Ayeb, M.; Luis, J.; Marrakchi, N. Leberagin-C, A disintegrin-like/cysteine-rich protein from Macrovipera lebetina transmediterranea venom, inhibits alphavbeta3 integrin-mediated cell adhesion. Matrix Biol. 2010, 29, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Brown, M.C.; Staniszewska, I.; Lazarovici, P.; Tuszynski, G.P.; Del Valle, L.; Marcinkiewicz, C. Regulatory effect of nerve growth factor in alpha9beta1 integrin-dependent progression of glioblastoma. Neuro. Oncol. 2008, 10, 968–980. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Brown, M.C.; Staniszewska, I.; Del Valle, L.; Tuszynski, G.P.; Marcinkiewicz, C. Angiostatic activity of obtustatin as alpha1beta1 integrin inhibitor in experimental melanoma growth. Int. J. Canc. 2008, 123, 2195–2203. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Staniszewska, I.; Walsh, E.M.; Rothman, V.L.; Gaathon, A.; Tuszynski, G.P.; Calvete, J.J.; Lazarovici, P.; Marcinkiewicz, C. Effect of VP12 and viperistatin on inhibition of collagen-receptor-dependent melanoma metastasis. Canc. Biol. Ther. 2009, 8, 1507–1516. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Serrano, S.M.; Wang, D.; Shannon, J.D.; Pinto, A.F.; Polanowska-Grabowska, R.K.; Fox, J.W. Interaction of the cysteine-rich domain of snake venom metalloproteinases with the A1 domain of von Willebrand factor promotes site-specific proteolysis of von Willebrand factor and inhibition of von Willebrand factor-mediated platelet aggregation. FEBS. J. 2007, 274, 3611–3621. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Moser, M.; Bauer, M.; Schmid, S.; Ruppert, R.; Schmidt, S.; Sixt, M.; Wang, H.V.; Sperandio, M.; Fassler, R. Kindlin-3 is required for beta2 integrin-mediated leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells. Nat. Med. 2009, 15, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Mochizuki, S.; Okada, Y. ADAMs in cancer cell proliferation and progression. Canc. Sci. 2007, 98, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Arribas, J.; Bech-Serra, J.J.; Santiago-Josefat, B. ADAMs, cell migration and cancer. Canc. Metastasis Rev. 2006, 25, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Seals, D.F.; Courtneidge, S.A. The ADAMs family of metalloproteases: multidomain proteins with multiple functions. Genes Dev. 2003, 17, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Jia, L.G.; Shimokawa, K.; Bjarnason, J.B.; Fox, J.W. Snake venom metalloproteinases: structure, function and relationship to the ADAMs family of proteins. Toxicon 1996, 34, 1269–1276. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Stone, A.L.; Kroeger, M.; Sang, Q.X. Structure-function analysis of the ADAM family of disintegrin-like and metalloproteinase-containing proteins (review). J. Protein Chem. 1999, 18, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Zigrino, P.; Steiger, J.; Fox, J.W.; Loffek, S.; Schild, A.; Nischt, R.; Mauch, C. Role of ADAM-9 disintegrin-cysteine-rich domains in human keratinocyte migration. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 30785–30793. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Mauch, C.; Zamek, J.; Abety, A.N.; Grimberg, G.; Fox, J.W.; Zigrino, P. Accelerated wound repair in ADAM-9 knockout animals. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2010, 130, 2120–2130. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Chen, Q.; Meng, L.H.; Zhu, C.H.; Lin, L.P.; Lu, H.; Ding, J. ADAM15 suppresses cell motility by driving integrin alpha5beta1 cell surface expression via Erk inactivation. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008, 40, 2164–2173. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Trochon-Joseph, V.; Martel-Renoir, D.; Mir, L.M.; Thomaidis, A.; Opolon, P.; Connault, E.; Li, H.; Grenet, C.; Fauvel-Lafeve, F.; Soria, J.; Legrand, C.; Soria, C.; Perricaudet, M.; Lu, H. Evidence of antiangiogenic and antimetastatic activities of the recombinant disintegrin domain of metargidin. Canc. Res. 2004, 64, 2062–2069. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Cominetti, M.R.; Martin, A.C.; Ribeiro, J.U.; Djaafri, I.; Fauvel-Lafeve, F.; Crepin, M.; Selistre-de-Araujo, H.S. Inhibition of platelets and tumor cell adhesion by the disintegrin domain of human ADAM9 to collagen I under dynamic flow conditions. Biochimie 2009, 91, 1045–1052. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Selistre-de-Araujo, H.S. 2010; Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, SP, Brazil. Unpublished work.

- Xu, Q.; Liu, X.; Cai, Y.; Yu, Y.; Chen, W. RNAi-mediated ADAM9 gene silencing inhibits metastasis of adenoid cystic carcinoma cells. Tumour Biol. 2010, 31, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Alfandari, D.; Cousin, H.; Gaultier, A.; Smith, K.; White, J.M.; Darribere, T.; DeSimone, D.W. Xenopus ADAM 13 is a metalloprotease required for cranial neural crest-cell migration. Curr. Biol. 2001, 11, 918–930. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Maretzky, T.; Reiss, K.; Ludwig, A.; Buchholz, J.; Scholz, F.; Proksch, E.; de Strooper, B.; Hartmann, D.; Saftig, P. ADAM10 mediates E-cadherin shedding and regulates epithelial cell-cell adhesion, migration, and beta-catenin translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 9182–9187. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Wild-Bode, C.; Fellerer, K.; Kugler, J.; Haass, C.; Capell, A. A basolateral sorting signal directs ADAM10 to adherens junctions and is required for its function in cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 23824–23829. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Guarino, M. Src signaling in cancer invasion. J. Cell Physiol. 2010, 223, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Ilina, O.; Friedl, P. Mechanisms of collective cell migration at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2009, 122, 3203–3208. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Friedl, P.; Noble, P.B.; Walton, P.A.; Laird, D.W.; Chauvin, P.J.; Tabah, R.J.; Black, M.; Zanker, K.S. Migration of coordinated cell clusters in mesenchymal and epithelial cancer explants in vitro. Canc. Res. 1995, 55, 4557–4560. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Christiansen, J.J.; Rajasekaran, A.K. Reassessing epithelial to mesenchymal transition as a prerequisite for carcinoma invasion and metastasis. Canc. Res. 2006, 66, 8319–8126. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

© 2010 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Selistre-de-Araujo, H.S.; Pontes, C.L.S.; Montenegro, C.F.; Martin, A.C.B.M. Snake Venom Disintegrins and Cell Migration. Toxins 2010, 2, 2606-2621. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins2112606

Selistre-de-Araujo HS, Pontes CLS, Montenegro CF, Martin ACBM. Snake Venom Disintegrins and Cell Migration. Toxins. 2010; 2(11):2606-2621. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins2112606

Chicago/Turabian StyleSelistre-de-Araujo, Heloisa S., Carmen L. S. Pontes, Cyntia F. Montenegro, and Ana Carolina B. M. Martin. 2010. "Snake Venom Disintegrins and Cell Migration" Toxins 2, no. 11: 2606-2621. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins2112606

APA StyleSelistre-de-Araujo, H. S., Pontes, C. L. S., Montenegro, C. F., & Martin, A. C. B. M. (2010). Snake Venom Disintegrins and Cell Migration. Toxins, 2(11), 2606-2621. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins2112606