Good Clinical Practices for the Management of Cervical Dystonia with BoNT-A: A Delphi-Based Approach from the Italian Expert Group

Abstract

1. Introduction

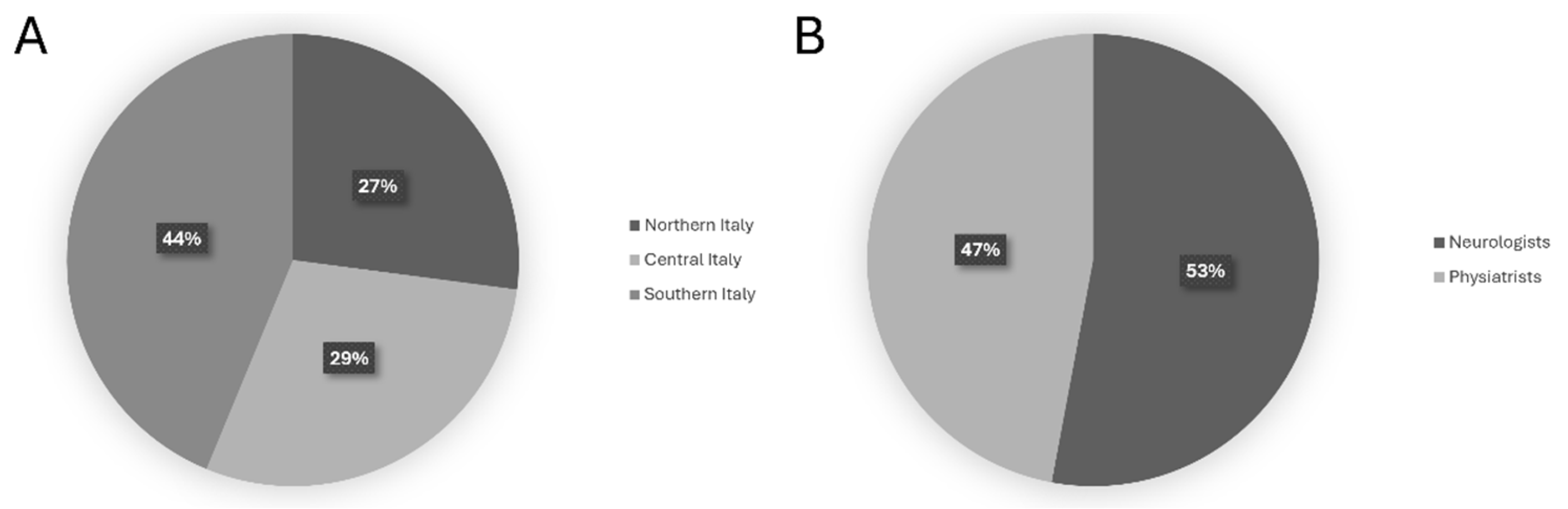

2. Results

| Domain: Conditions for Clinical Evaluation of the Patient | Consensus (%) |

| 1. It is necessary to evaluate patients while sitting at rest with their eyes open. | 96.2% |

| 2. It is necessary to evaluate patients while sitting at rest with their eyes closed. | 90.4% |

| 3. It is necessary to evaluate patients while seated at rest in the Mingazzini I position, with their eyes open. | 80.8% |

| 4. It is necessary to evaluate patients while seated at rest in the Mingazzini I position, with their eyes closed. | 80.8% |

| 5. It is necessary to evaluate the voluntary movement of the head across different planes while the patient is seated. | 98.0% |

| 6. It is necessary to evaluate the voluntary movement of the head across different planes while the patient is standing. | 96.2% |

| 7. It is necessary to evaluate the patient standing with the eyes open. | 92.3% |

| 8. It is necessary to evaluate the patient standing with the eyes closed. | 84.6% |

| 9. It is necessary to evaluate the patient while walking. | 100% |

| 10. It is necessary to evaluate the prevalent pattern of cervical dystonia. | 98.1% |

| 11. It is necessary to evaluate the severity of cervical dystonia. | 100% |

| Domain: Additional Evaluation Parameters Beyond the Predominant Pattern for Injection Target Selection | |

| 12. The tonic (postural) component of dystonia must be considered when choosing treatment targets. | 100% |

| 13. The phasic (mobile) component of dystonia must be considered when choosing treatment targets. | 98.1% |

| 14. Tremor must be considered when choosing treatment targets. | 98.1% |

| 15. Shoulder positioning must be considered when choosing treatment targets. | 100% |

| 16. Muscle trophism is an element to consider when choosing possible dosage targets. | 98.1% |

| 17. Pain is an element to consider when choosing targets. | 86.5% |

| Domain: Additional evaluation parameters to the severity of cervical dystonia for dosage selection | |

| 18. The tonic (postural) component of dystonia must be considered when choosing treatment dosages. | 92.3% |

| 19. The phasic (mobile) component of dystonia must be considered when choosing treatment dosages. | 90.3% |

| 20. Tremor must be considered when choosing treatment dosages. | 86.5% |

| 21. Shoulder positioning must be considered when choosing treatment dosages. | 82.7% |

| 22. Muscle trophism is an element to consider when choosing possible dosages. | 92.3% |

| 23. Pain is an element to consider when choosing treatment dosages. | 86.5% |

| 24. Dysphagia must be considered when choosing treatment dosages. | 90.4% |

| 25. Muscle trophism is an element to consider when choosing dosage. | 94.2% |

| Domain: Treatment with BoNT-A | |

| 26. At first inoculation, it is recommended to treat only the prevailing dystonic pattern. | 96.2% |

| 27. To optimize treatment, it is recommended to use instrumental guidance. | 96.1% |

| 28. To improve the localization of injection targets, it is preferable to use ultrasound guidance. | 92.3% |

| 29. To improve the identification of active targets, it is preferable to use EMG guidance. | 94.2% |

| 30. To optimize treatment in complex cases, it is recommended to use dual guidance. | 92.3% |

| 31. To optimize treatment in complex cases, it is recommended to perform a poly-EMG to identify the dystonic muscles to be treated. | 90.4% |

| 32. When facing an anterocollis/antecaput, it is necessary to perform dynamic cervical X-ray (e.g., with patients performing head flexion and extension) to identify involvement of deep muscles (long head–neck, e.g., longus collis, longus capitiis). | 42.3% |

| 33. When choosing the treatment, it is necessary to consider the patient’s expectations and adequately define the expected goals of the treatment with the patient and caregiver. | 98.1% |

| 34. In cases of head tremor, treatment of muscle groups bilaterally is necessary. | 84.6% |

| 35. Before starting treatment, it is appropriate to film the patient and the presence of abnormal postures. | 94.2% |

| Domain: Follow-up | |

| 36. When assessing post-treatment follow-up, it is recommended to use the Toronto Western Torticollis Rating Scale (TWTRS). | 90.4% |

| 37. When evaluating post-treatment follow-up, it is recommended to use the Tsui scale. | 84.7% |

| 38. When evaluating post-treatment follow-up, it is necessary to film the patient. | 90.4% |

| 39. It is necessary to perform at least four cycles of treatment before defining clinical nonresponse. | 88.4% |

| 40. In the poorly responsive or nonresponsive dystonic patient, a poly-EMG should be performed to identify the dystonic muscles to be treated. | 92.3% |

| 41. A dedicated follow-up for pain, regardless of the clinical changes in dystonic postures. | 71.2% |

| 42. In case of partial or no response, it is necessary to reevaluate the patient clinically and instrumentally (poly-EMG). | 94.3% |

| 43. In case of partial or no response, a neurophysiological test (Extensor Digitorum Brevis) should be performed to quantify and verify the response to the toxin (induced neuromuscular blockade). | 69.3% |

| 44. In evaluating the response to treatment, it is advisable to assess the psychological state of the patient. | 94.2% |

| 45. When evaluating treatment response, it is necessary to consider the patient’s expectations/adequately define the expected goals with the patient and caregiver. | 100% |

| Domain: Timing | |

| 46. After the first treatment, it is necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment between 4 and 6 weeks after inoculation. | 92.3% |

| 47. In post-treatment follow-up, it is recommended to wait at least 3 months before repeating inoculations with toxin. | 98.1% |

| 48. In post-treatment follow-up, in selected cases where clinical efficacy is very short, it is preferable to repeat the treatment after 2 months following the recurrence of symptoms. | 63.5% |

| 49. After each injection cycle, adverse events should be considered in order to optimize the choice of muscles to treat and the doses to be used. | 100% |

| Domain: Additional post-inoculation treatments | |

| 50. It is advisable to combine physiotherapy with toxin treatment. | 90.2% |

| 51. It is advisable to combine self-rehabilitation with toxin treatment. | 84.7% |

| 52. It is advisable to combine psychological treatment with toxin treatment in patients with emotional distress. | 90.3% |

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CD | Cervical Dystonia |

| BoNT-A | Botulinum Neurotoxin type A |

| DBS | Deep Brain Stimulation |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| R1 | Round 1 |

| R2 | Round 2 |

| TENS | Electrical Nerve Stimulation |

References

- Grutz, K.; Klein, C. Dystonia updates: Definition, nomenclature, clinical classification, and etiology. J. Neural Transm. 2021, 128, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinnah, H.A.; Berardelli, A.; Comella, C.; Defazio, G.; Delong, M.R.; Factor, S.; Galpern, W.R.; Hallett, M.; Ludlow, C.L.; Perlmutter, J.S.; et al. The focal dystonias: Current views and challenges for future research. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 926–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, B.D.; Groth, C.L.; Shelton, E.; Sillau, S.H.; Sutton, B.; Legget, K.T.; Tregellas, J.R. Hemodynamic responses are abnormal in isolated cervical dystonia. J. Neurosci. Res. 2020, 98, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erro, R.; Picillo, M.; Pellecchia, M.T.; Barone, P. Improving the efficacy of botulinum toxin for cervical dystonia: A scoping review. Toxins 2023, 15, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beylergil, S.B.; Mukunda, K.N.; Elkasaby, M.; Perlmutter, J.S.; Factor, S.; Bäumer, T.; Feurestein, J.; Shelton, E.; Bellows, S.; Jankovic, J.; et al. Tremor in cervical dystonia. Dystonia 2024, 3, 11309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukouni, V.; Martino, D.; Arabia, G.; Quinn, N.P.; Bhatia, K.P. The entity of young onset primary cervical dystonia. Mov. Disord. 2007, 22, 843–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defazio, G.; Belvisi, D.; Comella, C.; Hallett, M.; Jinnah, H.A.; Cimino, P.; Latorre, A.; Mascia, M.M.; Rocchi, L.; Gigante, A.F.; et al. Validation of a guideline to reduce variability in diagnosing cervical dystonia. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 2606–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinazzi, M.; Squintani, G.M.; Bhatia, K.P.; Segatti, A.; Donato, F.; Valeriani, M.; Erro, R. Pain in cervical dystonia: Evidence of abnormal inhibitory control. Park. Relat. Disord. 2019, 65, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, K.; Prilop, L.; Schön, G.; Gelderblom, M.; Misselhorn, J.; Gerloff, C.; Zittel, S. Cerebellar modulation of sensorimotor associative plasticity is impaired in cervical dystonia. Mov. Disord. 2023, 38, 2084–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetterberg, L.; Urell, C.; Anens, E. Exploring factors related to physical activity in cervical dystonia. BMC Neurol. 2015, 15, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, A.; Di Giovanni, M.; Lalli, S. Dystonia: Diagnosis and management. Eur. J. Neurol. 2019, 26, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudente, C.N.; Zetterberg, L.; Bring, A.; Bradnam, L.; Kimberley, T.J. Systematic Review of Rehabilitation in Focal Dystonias: Classification and Recommendations. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2018, 5, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evidente, V.G.; Pappert, E.J. Botulinum toxin therapy for cervical dystonia: The science of dosing. Tremor Other Hyperkinet. Mov. 2014, 4, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochim, A.; Meindl, T.; Mantel, T.; Zwirner, S.; Zech, M.; Castrop, F.; Haslinger, B. Treatment of cervical dystonia with abo- and onabotulinumtoxinA: Long-term safety and efficacy in daily clinical practice. J. Neurol. 2019, 266, 1879–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosales, R.L.; Cuffe, L.; Regnault, B.; Trosch, R.M. Pain in cervical dystonia: Mechanisms, assessment and treatment. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2021, 21, 1125–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Jeong, H.; Chung, Y.-A.; Kang, I.; Kim, S.; Song, I.-U.; Huh, R. Changes of regional cerebral blood flow after deep brain stimulation in cervical dystonia. EJNMMI Res. 2022, 12, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, A.; Bhatia, K.P.; Cardoso, F.; Comella, C.; Defazio, G.; Fung, V.S.; Hallett, M.; Jankovic, J.; Jinnah, H.A.; Kaji, R.; et al. Isolated cervical dystonia: Diagnosis and classification. Mov. Disord. 2023, 38, 1367–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassaye, S.G.; De Hertogh, W.; Crosiers, D.; Gudina, E.K.; De Pauw, J. The effectiveness of physiotherapy for patients with isolated cervical dystonia: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol. 2024, 24, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Ebersbach, G.; Wissel, J.; Brenneis, C.; Badry, L.; Poewe, W. Disturbances of dynamic balance in phasic cervical dystonia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1999, 67, 807–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pablo-Fernandez, E.; Warner, T.T. Dystonia. Br. Med. Bull. 2017, 123, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, P.D.; Manack Adams, A.; Davis, T.; Bradley, K.; Schwartz, M.; Brin, M.F.; Patel, A.T. Neck pain and cervical dystonia: Treatment outcomes from CD PROBE (Cervical Dystonia Patient Registry for Observation of OnabotulinumtoxinA Efficacy). Pain Pract. 2016, 16, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centen, L.M.; van Egmond, M.E.; Tijssen, M.A.J. New developments in diagnostics and treatment of adult-onset focal dystonia. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2023, 36, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyślerowicz, M.; Kiedrzyńska, W.; Adamkiewicz, B.; Jost, W.H.; Sławek, J. Cervical dystonia: Improving the effectiveness of botulinum toxin therapy. Neurol. Neurochir. Pol. 2020, 54, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreisler, A.; Mortain, L.; Watel, K.; Mutez, E.; Defebvre, L.; Duhamel, A. Doses of botulinum toxin in cervical dystonia: Does ultrasound guidance change injection practices? Toxins 2024, 16, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comella, C.; Ferreira, J.J.; Pain, E.; Azoulai, M.; Om, S. Patient perspectives on the therapeutic profile of botulinum neurotoxin type A in cervical dystonia. J. Neurol. 2021, 268, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cisneros, E.; Lee, H.Y.; Vu, J.P.; Chen, Q.; Benadof, C.N.; Whitehill, J.; Rouzbehani, R.; Sy, D.T.; Huang, J.S.; et al. Hold that pose: Capturing cervical dystonia’s head deviation severity from video. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2022, 9, 684–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaya, H.; Colakoglu, Z.; Acarer, A.; Ozkurt, A. A new method for the evaluation of cervical dystonia. Turk. J. Neurol. 2025, 31, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, M.J.; Canning, C.G.; Mahant, N.; Morris, J.; Latimer, J.; Fung, V.S. The Toronto Western Spasmodic Torticollis Rating Scale: Reliability in neurologists and physiotherapists. Park. Relat. Disord. 2012, 18, 635–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espay, A.J.; Trosch, R.; Suarez, G.; Johnson, J.; Marchese, D.; Comella, C. Minimal clinically important change in the Toronto Western Spasmodic Torticollis Rating Scale. Park. Relat. Disord. 2018, 52, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, W.H.; Hefter, H.; Stenner, A.; Reichel, G. Rating scales for cervical dystonia: A critical evaluation of tools for outcome assessment of botulinum toxin therapy. J. Neural Transm. 2013, 120, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.J.; Bhidayasiri, R.; Colosimo, C.; Marti, M.J.; Zakine, B.; Maisonobe, P. Survey of practices employed by neurologists for the definition and management of secondary nonresponse to botulinum toxin in cervical dystonia. Funct. Neurol. 2012, 27, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marion, M.H.; Humberstone, M.; Grunewald, R.; Wimalaratna, S. British Neurotoxin Network recommendations for managing cervical dystonia in patients with a poor response to botulinum toxin. Pract. Neurol. 2016, 16, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erro, R.; Bhatia, K.P.; Esposito, M.; Cordivari, C. The role of polymyography in the treatment of cervical dystonia. J. Neurol. 2016, 263, 1663–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowling, H.; O’Keeffe, F.; Eccles, F.J.R. Stigma, coping strategies, distress and wellbeing in individuals with cervical dystonia: A cross-sectional study. Psychol. Health Med. 2024, 29, 1313–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagna, A.; Saibene, E.; Ramella, M. How do I rehabilitate patients with cervical dystonia remotely? Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2021, 8, 820–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacksch, C.; Loens, S.; Mueller, J.; Tadic, V.; Bäumer, T.; Zeuner, K.E. Impact of physiotherapy in the treatment of pain in cervical dystonia. Tremor Other Hyperkinet. Mov. 2024, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linstone, H.A.; Turoff, M. The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 1975; Available online: https://www.foresight.pl/assets/downloads/publications/Turoff_Linstone.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Murphy, M.K.; Black, N.A.; Lamping, D.L.; McKee, C.M.; Sanderson, C.F.; Askham, J.; Marteau, T. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol. Assess. 1998, 2, 1–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasa, P.; Jain, R.; Juneja, D. Delphi methodology in healthcare research: How to decide its appropriateness. World J. Methodol. 2021, 11, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E. We agree, don’t we? The Delphi method for health environments research. HERD 2020, 13, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkey, N.C. The Delphi Method: An Experimental Study of Group Opinion; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

| Amended Statements | Consensus (%) |

|---|---|

| 41.1 In post-inoculation, it is necessary to assess the pain symptom response independently of the dystonic motor response. | 80.0% |

| 43.1 To assess immune resistance to botulinum toxin, after repeated treatments with appropriate doses and targets with partial or no clinical response, it is recommended to perform neurophysiological testing (e.g., EDB Test). | 92.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Eleopra, R.; Esposito, M.; Bentivoglio, A.R.; Altavista, M.C.; Erro, R.; Caglioni, P.M.; Castagna, A. Good Clinical Practices for the Management of Cervical Dystonia with BoNT-A: A Delphi-Based Approach from the Italian Expert Group. Toxins 2026, 18, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18020079

Eleopra R, Esposito M, Bentivoglio AR, Altavista MC, Erro R, Caglioni PM, Castagna A. Good Clinical Practices for the Management of Cervical Dystonia with BoNT-A: A Delphi-Based Approach from the Italian Expert Group. Toxins. 2026; 18(2):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18020079

Chicago/Turabian StyleEleopra, Roberto, Marcello Esposito, Anna Rita Bentivoglio, Maria Concetta Altavista, Roberto Erro, Patrizia Maria Caglioni, and Anna Castagna. 2026. "Good Clinical Practices for the Management of Cervical Dystonia with BoNT-A: A Delphi-Based Approach from the Italian Expert Group" Toxins 18, no. 2: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18020079

APA StyleEleopra, R., Esposito, M., Bentivoglio, A. R., Altavista, M. C., Erro, R., Caglioni, P. M., & Castagna, A. (2026). Good Clinical Practices for the Management of Cervical Dystonia with BoNT-A: A Delphi-Based Approach from the Italian Expert Group. Toxins, 18(2), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18020079