Evaluation of a Cell-Based Potency Assay for Detection of the Potency of TrenibotulinumtoxinE® (TrenibotE)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Accuracy

2.2. Intermediate Precision

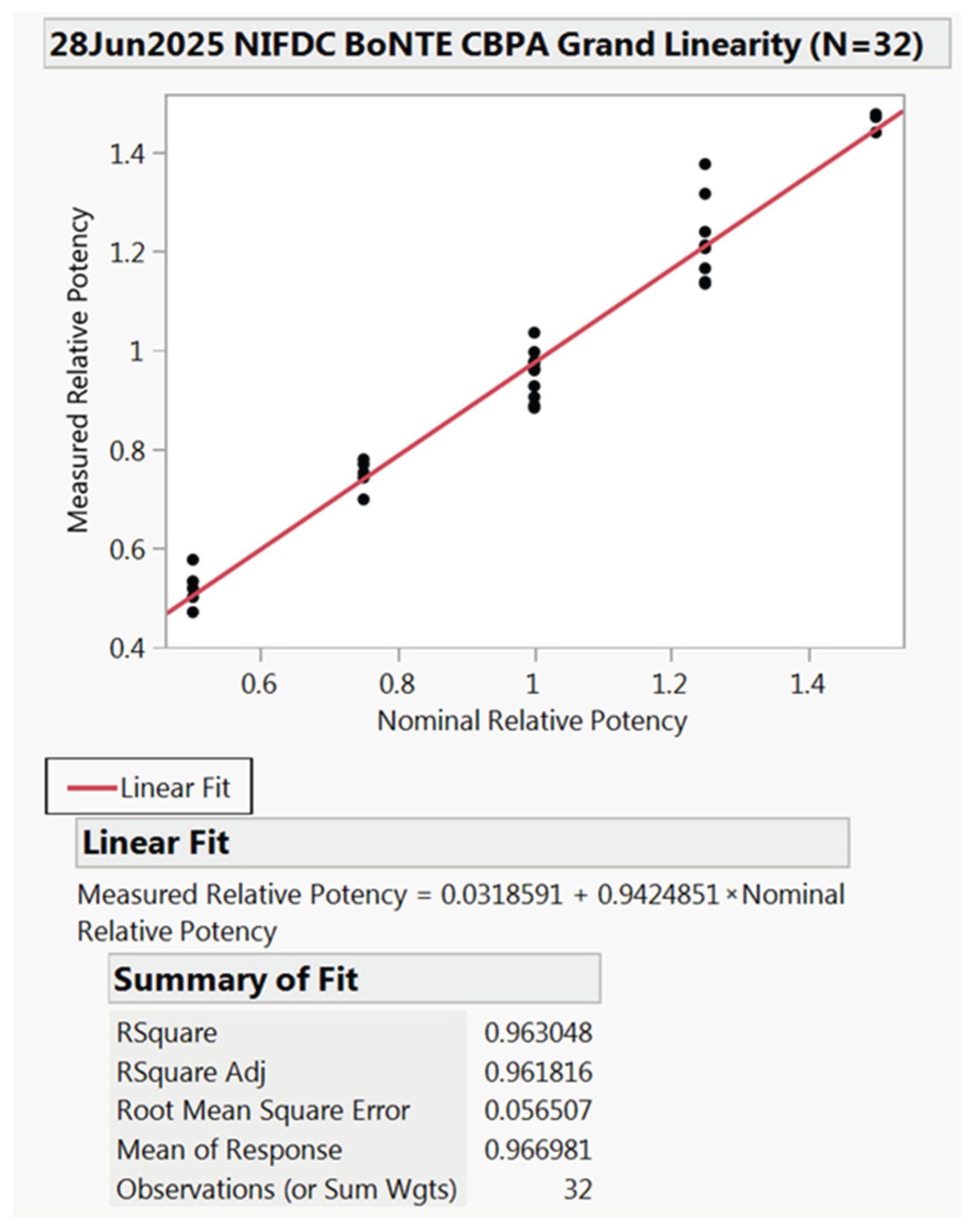

2.3. Linearity

2.4. Repeatability

2.5. Range

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Sample Preparations

5.2. The CBPA Methodology [16]

5.2.1. Cell Growth and Differentiation (Days 1–8)

5.2.2. Cell Treatment and Cleavage of SNAP25180 (Day 9)

5.2.3. Cells Lysis and Quantification of SNAP25180 (Day 10)

5.2.4. Data Analysis

5.3. Method Validation

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BoNT/A | Botulinum Toxin Type A |

| BoNT/E | Botulinum Toxin Type E |

| CBPA | Cell-Based Potency Assay |

| RS | Reference Standard |

| LD50 | Median lethal dose |

| 3-Rs | Reduction Replacement Refinement |

References

- Simpson, L.L. Identification of the characteristics that underlie botulinum toxin potency: Implications for designing novel drugs. Biochimie 2000, 82, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habermann, E.; Dreyer, F. Clostridial neurotoxins: Handling and action at the cellular and molecular level. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 1986, 129, 93–179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peck, M.W. Biology and genomic analysis of Clostridium botulinum. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 2009, 55, 183–265, 320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leclair, D.; Farber, J.M.; Doidge, B.; Blanchfield, B.; Suppa, S.; Pagotto, F.; Austin, J.W. Distribution of Clostridium botulinum type E strains in Nunavik, Northern Quebec, Canada. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.W.; Wang, C.H. An overview of type E botulism in China. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2008, 21, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Südhof, T.C. The molecular machinery of neurotransmitter release (Nobel lecture). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 12696–12717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, S.; Montecucco, C. The blockade of the neurotransmitter release apparatus by botulinum neurotoxins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 793–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tighe, A.P.; Schiavo, G. Botulinum neurotoxins: Mechanism of action. Toxicon 2013, 67, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.P.; Berris, C.E. Botulinum toxin: A treatment for facial asymmetry caused by facial nerve paralysis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1989, 84, 353–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, V.; Carre, D.; Bilbault, H.; Oster, S.; Limana, L.; Sebal, F.; Favre-Guilmard, C.; Kalinichev, M.; Leveque, C.; Boulifard, V.; et al. Intramuscular Botulinum Neurotoxin Serotypes E and A Elicit Distinct Effects on SNAP25 Protein Fragments, Muscular Histology, Spread and Neuronal Transport: An Integrated Histology-Based Study in the Rat. Toxins 2024, 16, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, L.; Vilain, C.; Volteau, M.; Picaut, P. Safety and pharmacodynamics of a novel recombinant botulinum toxin E (rBoNT-E): Results of a phase 1 study in healthy male subjects compared with abobotulinumtoxinA (Dysport®). J. Neurol. Sci. 2019, 407, 116516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutschenko, A.; Weisemann, J.; Kollewe, K.; Fiedler, T.; Alvermann, S.; Böselt, S.; Escher, C.; Garde, N.; Gingele, S.; Kaehler, S.B.; et al. Botulinum neurotoxin serotype D—A potential treatment alternative for BoNT/A and B non-responding patients. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2019, 130, 1066–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoelin, S.G.; Dhawan, S.S.; Vitarella, D.; Ahmad, W.; Hasan, F.; Abushakra, S. Safety and Efficacy of EB-001, a Novel Type E Botulinum Toxin, in Subjects with Glabellar Frown Lines: Results of a Phase 2, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Ascending-Dose Study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2018, 142, 847e–855e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, G.S.; Canty, D.; Southern, A.; Whelan, K.; Brideau-Andersen, A.D.; Broide, R.S. Preclinical Evaluation of Botulinum Toxin Type E (TrenibotulinumtoxinE) Using the Mouse Digit Abduction Score (DAS) Assay. Toxins 2025, 17, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasetti-Escargueil, C.; Popoff, M.R. Recent Developments in Botulinum Neurotoxins Detection. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Salas, E.; Wang, J.; Molina, Y.; Nelson, J.B.; Jacky, B.P.; Aoki, K.R. Botulinum neurotoxin serotype A specific cell-based potency assay to replace the mouse bioassay. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonfria, E.; Marks, E.; Foulkes, L.M.; Schofield, R.; Higazi, D.; Coward, S.; Kippen, A. Replacement of the Mouse LD(50) Assay for Determination of the Potency of AbobotulinumtoxinA with a Cell-Based Method in Both Powder and Liquid Formulations. Toxins 2023, 15, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, S.; Bicker, G.; Bigalke, H.; Bishop, C.; Blümel, J.; Dressler, D.; Fitzgerald, J.; Gessler, F.; Heuschen, H.; Kegel, B.; et al. The current scientific and legal status of alternative methods to the LD50 test for botulinum neurotoxin potency testing. The report and recommendations of a ZEBET Expert Meeting. Altern. Lab. Anim. 2010, 38, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, L.; Wang, S.; Ma, X. A Validation of the Equivalence of the Cell-Based Potency Assay Method with a Mouse LD50 Bioassay for the Potency Testing of OnabotulinumtoxinA. Toxins 2024, 16, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binz, T.; Blasi, J.; Yamasaki, S.; Baumeister, A.; Link, E.; Südhof, T.C.; Jahn, R.; Niemann, H. Proteolysis of SNAP-25 by types E and A botulinal neurotoxins. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 1617–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavo, G.; Santucci, A.; Dasgupta, B.R.; Mehta, P.P.; Jontes, J.; Benfenati, F.; Wilson, M.C.; Montecucco, C. Botulinum neurotoxins serotypes A and E cleave SNAP-25 at distinct COOH-terminal peptide bonds. FEBS Lett. 1993, 335, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merz Pharma GmbH; Marx, C.K.K. Alternative Test Method for Botulinum Neurotoxin Now Approved in Europe [Press Release]. Available online: https://www.merz.com//wp-content/uploads/2015/12/20151211PM-BfArM-Zulassung-alternative-Testmethode_EN_v.pdf (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Foran, P.G.; Mohammed, N.; Lisk, G.O.; Nagwaney, S.; Lawrence, G.W.; Johnson, E.; Smith, L.; Aoki, K.R.; Dolly, J.O. Evaluation of the therapeutic usefulness of botulinum neurotoxin B, C1, E, and F compared with the long lasting type A. Basis for distinct durations of inhibition of exocytosis in central neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 1363–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodruff, B.A.; Griffin, P.M.; McCroskey, L.M.; Smart, J.F.; Wainwright, R.B.; Bryant, R.G.; Hutwagner, L.C.; Hatheway, C.L. Clinical and laboratory comparison of botulism from toxin types A, B, and E in the United States, 1975–1988. J. Infect. Dis. 1992, 166, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eleopra, R.; Tugnoli, V.; Rossetto, O.; De Grandis, D.; Montecucco, C. Different time courses of recovery after poisoning with botulinum neurotoxin serotypes A and E in humans. Neurosci. Lett. 1998, 256, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torii, Y.; Goto, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Ishida, S.; Harakawa, T.; Sakamoto, T.; Kaji, R.; Kozaki, S.; Ginnaga, A. Quantitative determination of biological activity of botulinum toxins utilizing compound muscle action potentials (CMAP), and comparison of neuromuscular transmission blockage and muscle flaccidity among toxins. Toxicon 2010, 55, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, F.A.; Lisk, G.; Sesardic, D.; Dolly, J.O. Dynamics of motor nerve terminal remodeling unveiled using SNARE-cleaving botulinum toxins: The extent and duration are dictated by the sites of SNAP-25 truncation. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2003, 22, 454–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janz, R.; Südhof, T.C. SV2C is a synaptic vesicle protein with an unusually restricted localization: Anatomy of a synaptic vesicle protein family. Neuroscience 1999, 94, 1279–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholome, O.; Van den Ackerveken, P.; Sánchez Gil, J.; de la Brassinne Bonardeaux, O.; Leprince, P.; Franzen, R.; Rogister, B. Puzzling Out Synaptic Vesicle 2 Family Members Functions. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.M.; Janz, R.; Belizaire, R.; Frishman, L.J.; Sherry, D.M. Differential distribution and developmental expression of synaptic vesicle protein 2 isoforms in the mouse retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 2003, 460, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonfria, E.; Maignel, J.; Lezmi, S.; Martin, V.; Splevins, A.; Shubber, S.; Kalinichev, M.; Foster, K.; Picaut, P.; Krupp, J. The Expanding Therapeutic Utility of Botulinum Neurotoxins. Toxins 2018, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuyer, G.; Chaddock, J.A.; Foster, K.A.; Acharya, K.R. Engineered botulinum neurotoxins as new therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014, 54, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lee, P.G.; Krez, N.; Lam, K.H.; Liu, H.; Przykopanski, A.; Chen, P.; Yao, G.; Zhang, S.; Tremblay, J.M.; et al. Structural basis for botulinum neurotoxin E recognition of synaptic vesicle protein 2. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, N.; Rajagopal, S.; Stickings, P.; Sesardic, D. SiMa Cells for a Serotype Specific and Sensitive Cell-Based Neutralization Test for Botulinum Toxin A and E. Toxins 2017, 9, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamant, E.; Torgeman, A.; Epstein, E.; Mechaly, A.; David, A.B.; Levin, L.; Schwartz, A.; Dor, E.; Girshengorn, M.; Barnea, A.; et al. A cell-based alternative to the mouse potency assay for pharmaceutical type E botulinum antitoxins. ALTEX 2022, 39, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellett, S.; Tepp, W.H.; Johnson, E.A.; Sesardic, D. Assessment of ELISA as endpoint in neuronal cell-based assay for BoNT detection using hiPSC derived neurons. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 2017, 88, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nominal Relative Potency (%) | Measured Relative Potency | Accuracy (%) | Mean Accuracy (%) | % CV (Precision per Level) | Overall Accuracy | Overall Intermediate Precision (%CV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 (n = 5) a | 0.500 | 100 | 104 | 7.5 | 98 | 5.4 |

| 0.532 | 107 | |||||

| 0.518 | 104 | |||||

| 0.576 | 115 | |||||

| 0.470 | 94 | |||||

| 75 (n = 5) a | 0.769 | 103 | 100 | 4.3 | ||

| 0.698 | 93 | |||||

| 0.779 | 104 | |||||

| 0.752 | 100 | |||||

| 0.742 | 99 | |||||

| 100 (n = 5) a | 0.905 | 91 | 93 | 6.9 | ||

| 0.996 | 100 | |||||

| 0.927 | 93 | |||||

| 0.883 | 88 | |||||

| 1.035 | 104 | |||||

| 125 (n = 8) a | 1.134 | 91 | 98 | 6.9 | ||

| 1.165 | 93 | |||||

| 1.212 | 97 | |||||

| 1.376 | 110 | |||||

| 1.316 | 105 | |||||

| 1.138 | 91 | |||||

| 1.239 | 99 | |||||

| 1.206 | 96 | |||||

| 150 (n = 3) a | 1.471 | 98 | 98 | 1.2 | ||

| 1.440 | 96 | |||||

| 1.477 | 98 |

| Parameter | Relative Potency Level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50% | 75% | 100% | 125% | 150% | |

| Mean Relative Potency (%) | 51.9 | 74.8 | 94.8 | 122.3 | 146.3 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.039 | 0.031 | 0.047 | 0.086 | 0.020 |

| CV (%) | 7.57 | 4.20 | 6.96 | 6.99 | 1.369 |

| Acceptance Criteria | ≤13% | ≤13% | ≤8% | ≤13% | ≤13% |

| Overall CV (%) | 6.28 | ||||

| Potency Level | RS and TS | Measured Relative Potency | Recovery [%] | Mean Recovery (%) | Standard Deviation | CV% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% | 13858WP-01 | 0.996 | 100 | 97 | 0.023 | 2.38 |

| 0.973 | 97 | |||||

| 0.927 | 93 | |||||

| 0.963 | 96 | |||||

| 0.959 | 96 | |||||

| 0.977 | 98 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Xue, Y.; Yuan, L. Evaluation of a Cell-Based Potency Assay for Detection of the Potency of TrenibotulinumtoxinE® (TrenibotE). Toxins 2026, 18, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010019

Yang Y, Zhang H, Wang S, Xue Y, Yuan L. Evaluation of a Cell-Based Potency Assay for Detection of the Potency of TrenibotulinumtoxinE® (TrenibotE). Toxins. 2026; 18(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yingchao, Huajie Zhang, Shuo Wang, Yanhua Xue, and Liyong Yuan. 2026. "Evaluation of a Cell-Based Potency Assay for Detection of the Potency of TrenibotulinumtoxinE® (TrenibotE)" Toxins 18, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010019

APA StyleYang, Y., Zhang, H., Wang, S., Xue, Y., & Yuan, L. (2026). Evaluation of a Cell-Based Potency Assay for Detection of the Potency of TrenibotulinumtoxinE® (TrenibotE). Toxins, 18(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010019