Immunological Considerations of Polysorbate as an Excipient in Botulinum Neurotoxin Type A Formulations: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

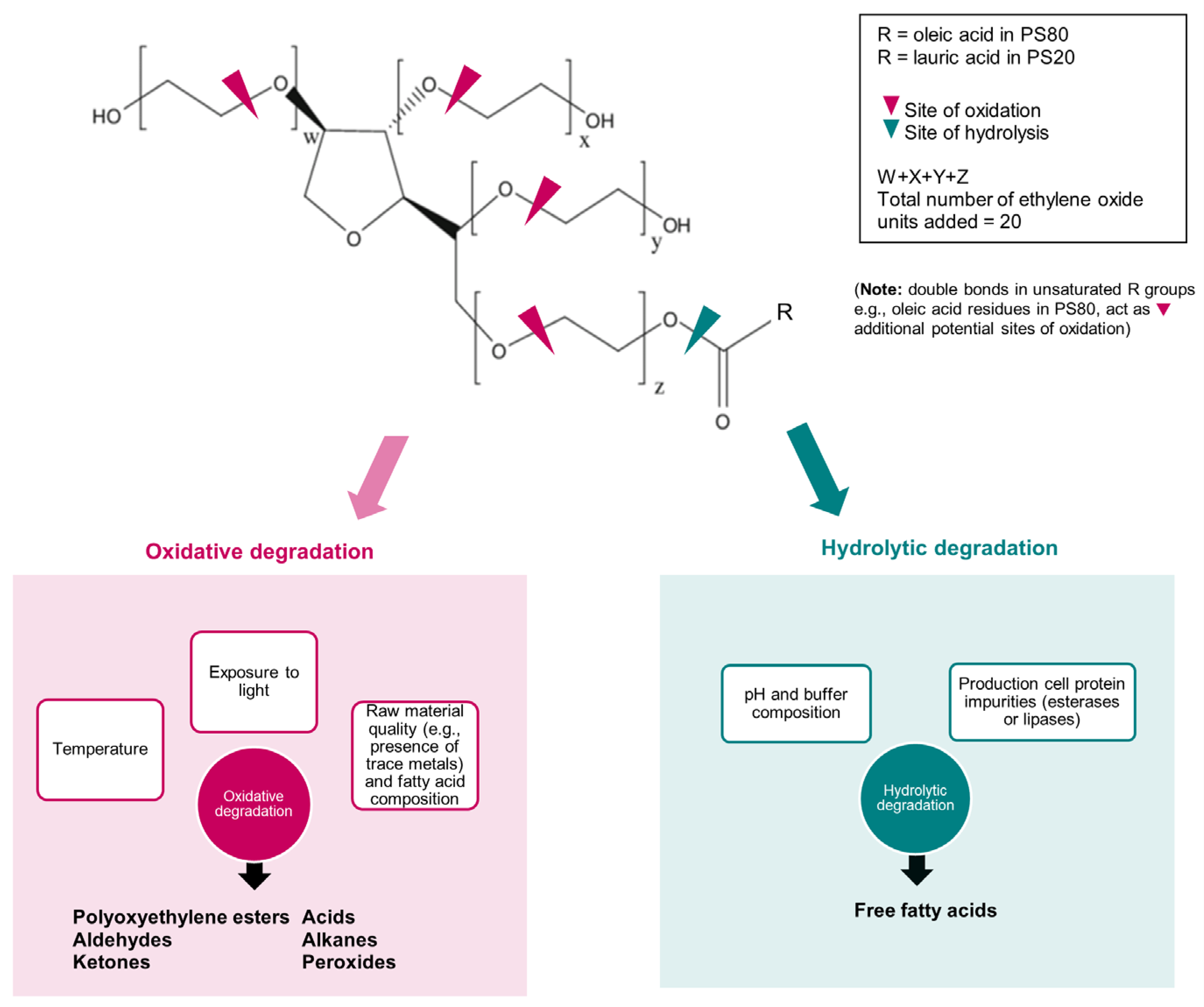

2. Chemical Nature and Degradation of Polysorbates

3. Mechanistic Insights and Clinical Implications

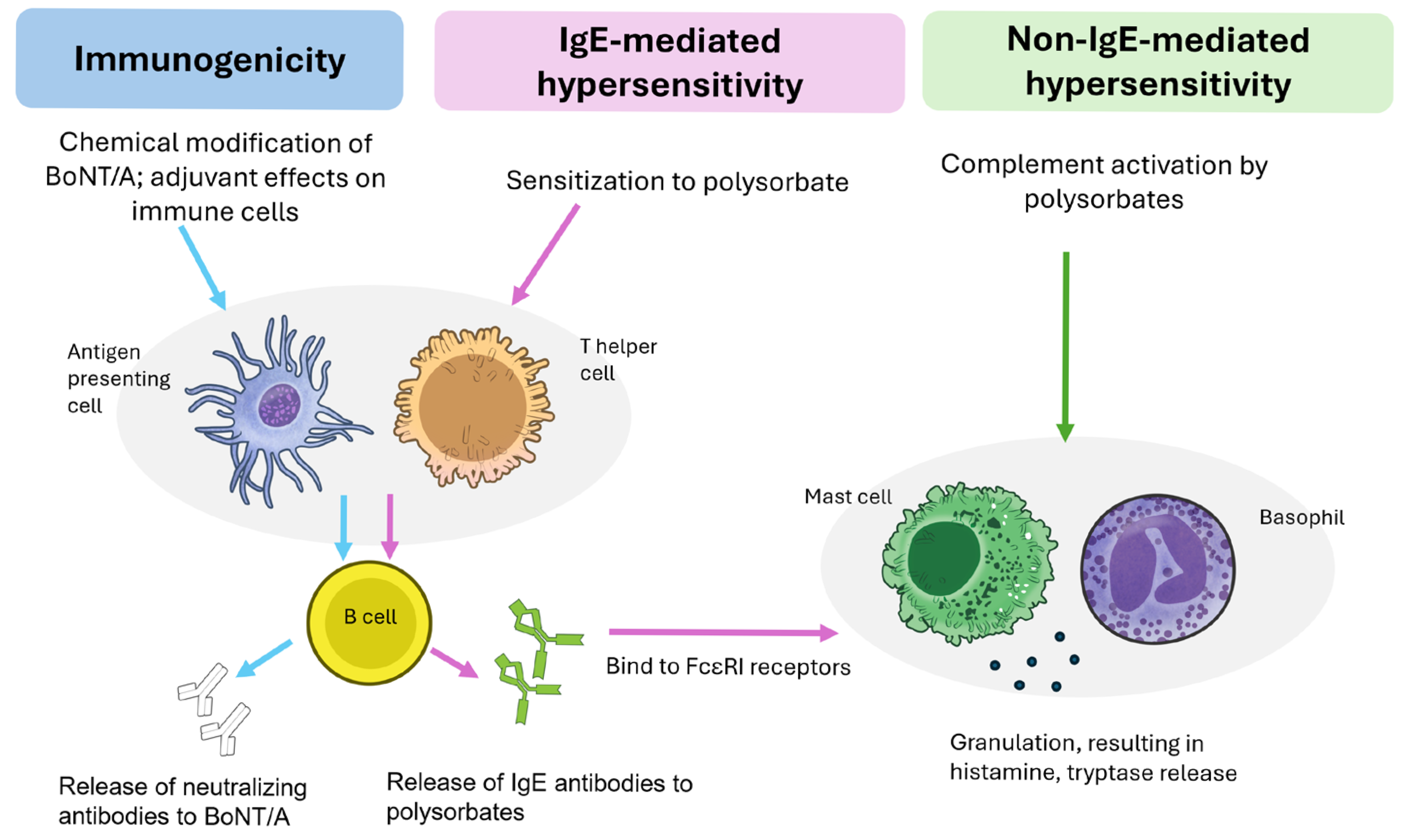

3.1. Risk of Developing Neutralizing Antibodies and Secondary Nonresponse

3.2. Hypersensitivity Reactions

3.2.1. Non-IgE Mediated Reactions

3.2.2. IgE Mediated Reactions

3.3. Current Clinical Experience with Polysorbate-Containing BoNT/A Formulations

4. Risk Mitigation

4.1. Manufacturers

4.2. Clinicians

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BoNT/A | Botulinum neurotoxin type A |

| CARPA | Complement Activation-Related Pseudoallergy |

| CHO | Chinese Hamster Ovary |

| CRISPR | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| HSA | Human serum albumin |

| IgE | Immunoglobulin E |

| NAb | Neutralizing antibody |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| PS20 | Polysorbate 20 |

| PS80 | Polysorbate 80 |

| RT | Room temperature |

| RTU | Ready-to-use |

References

- Sattler, S.; Gollomp, S.; Curry, A. A Narrative Literature Review of the Established Safety of Human Serum Albumin Use as a Stabilizer in Aesthetic Botulinum Toxin Formulations Compared to Alternatives. Toxins 2023, 15, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Kwak, S.; Park, M.-S.; Rhee, C.-H.; Yang, G.-H.; Lee, J.; Son, W.-C.; Kang, W. Safety Verification for Polysorbate 20, Pharmaceutical Excipient for Intramuscular Administration, in Sprague-Dawley Rats and New Zealand White Rabbits. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, M.T.; Mahler, H.-C.; Yadav, S.; Bindra, D.; Corvari, V.; Fesinmeyer, R.M.; Gupta, K.; Harmon, A.M.; Hinds, K.D.; Koulov, A.; et al. Considerations for the Use of Polysorbates in Biopharmaceuticals. Pharm. Res. 2018, 35, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartzberg, L.S.; Navari, R.M. Safety of Polysorbate 80 in the Oncology Setting. Adv. Ther. 2018, 35, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W.W.S.; Albrecht, P.; Calderon, P.E.; Corduff, N.; Loh, D.; Martin, M.U.; Park, J.-Y.; Suseno, L.S.; Tseng, F.-W.; Vachiramon, V.; et al. Emerging Trends in Botulinum Neurotoxin A Resistance: An International Multidisciplinary Review and Consensus. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2022, 10, e4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, C.; Perrin, H.; Combadiere, B. Tailored Immunity by Skin Antigen-Presenting Cells. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2015, 11, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.; Buske, J.; Mäder, K.; Garidel, P.; Diederichs, T. Oxidation of Polysorbates—An Underestimated Degradation Pathway? Int. J. Pharm. X 2023, 6, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Liu, Z.; Hou, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Du, W.; Wang, W.; Qin, Y.; Liu, Z. Complement Activation Associated with Polysorbate 80 in Beagle Dogs. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2013, 15, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coors, E.A.; Seybold, H.; Merk, H.F.; Mahler, V. Polysorbate 80 in Medical Products and Nonimmunologic Anaphylactoid Reactions. Ann. Allergy. Asthma. Immunol. 2005, 95, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuchner, K.; Yi, L.; Chery, C.; Nikels, F.; Junge, F.; Crotts, G.; Rinaldi, G.; Starkey, J.A.; Bechtold-Peters, K.; Shuman, M.; et al. Industry Perspective on the Use and Characterization of Polysorbates for Biopharmaceutical Products Part 2: Survey Report on Control Strategy Preparing for the Future. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 111, 2955–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozuch, B.; Weber, J.; Buske, J.; Mäder, K.; Garidel, P.; Diederichs, T. Comparative Stability Study of Polysorbate 20 and Polysorbate 80 Related to Oxidative Degradation. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kranz, W.; Wuchner, K.; Corradini, E.; Berger, M.; Hawe, A. Factors Influencing Polysorbate’s Sensitivity Against Enzymatic Hydrolysis and Oxidative Degradation. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 108, 2022–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.K.; Mahler, H.C.; Hartman, C.; Stark, C.A. Are Injection Site Reactions in Monoclonal Antibody Therapies Caused by Polysorbate Excipient Degradants? J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 107, 2735–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggio, E.T. Reducing or Eliminating Polysorbate Induced Anaphylaxis and Unwanted Immunogenicity in Biotherapeutics. J. Excip. Food Chem. 2017, 8, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Sun, H.; Yang, H.; Yang, R.; Zhu, X.; Guo, S.; Huang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, C.; Tu, J.; et al. Dessecting the toxicological profile of polysorbate 80 (PS80): Comparative analysis of constituent variability and biological impact using a zebrafish model. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 198, 106796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöneich, C. Primary Processes of Free Radical Formation in Pharmaceutical Formulations of Therapeutic Proteins. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saggu, M.; Demeule, B.; Jiang, L.; Kammerer, D.; Nayak, P.K.; Tai, M.; Xiao, N.; Tomlinson, A. Extended Characterization and Impact of Visible Fatty Acid Particles—A Case Study with a mAb Product. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 110, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Shen, G.; Chai, R.; Gamache, P.H.; Jin, Y. A Review of Polysorbate Quantification and Its Degradation Analysis by Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Charged Aerosol Detection. J. Chromatogr. A 2025, 1742, 465651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebaihia, M.; Peck, M.W.; Minton, N.P.; Thomson, N.R.; Holden, M.T.G.; Mitchell, W.J.; Carter, A.T.; Bentley, S.D.; Mason, D.R.; Crossman, L.; et al. Genome Sequence of a Proteolytic (Group I) Clostridium Botulinum Strain Hall A and Comparative Analysis of the Clostridial Genomes. Genome Res. 2007, 17, 1082–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perz, V.; Baumschlager, A.; Bleymaier, K.; Zitzenbacher, S.; Hromic, A.; Steinkellner, G.; Pairitsch, A.; Łyskowski, A.; Gruber, K.; Sinkel, C.; et al. Hydrolysis of Synthetic Polyesters by Clostridium Botulinum Esterases. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2016, 113, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, S.; Hamilton, M.; Sanches, E.; Starovatova, P.; Gubanova, E.; Reshetnikova, R. Neutralizing antibodies to botulinum neurotoxin type A in aesthetic medicine: Five case reports. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 7, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.U.; Frevert, J.; Tay, C.M. Complexing Protein-Free Botulinum Neurotoxin A Formulations: Implications of Excipients for Immunogenicity. Toxins 2024, 16, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.J. Protein Oxidation and Peroxidation. Biochem. J. 2016, 473, 805–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, C.A.; Pérez De La Lastra, J.M.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. The Chemistry of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Revisited: Outlining Their Role in Biological Macromolecules (DNA, Lipids and Proteins) and Induced Pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allison, M.E.D.; Fearon, D.T. Enhanced Immunogenicity of Aldehyde-Bearing Antigens: A Possible Link between Innate and Adaptive Immunity. Eur. J. Immunol. 2000, 30, 2881–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarkhed, M.; O’Dell, C.; Hsieh, M.-C.; Zhang, J.; Goldstein, J.; Srivastava, A. Effect of Polysorbate 80 Concentration on Thermal and Photostability of a Monoclonal Antibody. AAPS PharmSciTech 2013, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Matthew Fesinmeyer, R.; Pierini, C.J.; Siska, C.C.; Litowski, J.R.; Brych, S.; Wen, Z.-Q.; Kleemann, G.R. Free Fatty Acid Particles in Protein Formulations, Part 1: Microspectroscopic Identification. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 104, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; He, J.; Smith, K.J. Fatty Acids Can Induce the Formation of Proteinaceous Particles in Monoclonal Antibody Formulations. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 111, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundahl, M.L.E.; Fogli, S.; Colavita, P.E.; Scanlan, E.M. Aggregation of Protein Therapeutics Enhances Their Immunogenicity: Causes and Mitigation Strategies. RSC Chem. Biol. 2021, 2, 1004–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemen, R.; Arlt, K.; Von Woedtke, T.; Bekeschus, S. Gas Plasma Protein Oxidation Increases Immunogenicity and Human Antigen-Presenting Cell Maturation and Activation. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campion, C.L. Investigating the Effect of Oxidation on Immunogenicity of Protein Therapeutics. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, 2018. Available online: https://research.manchester.ac.uk/en/studentTheses/investigating-the-effect-of-oxidation-on-the-immunogenicity-of-pr (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Al-Thamir, S.N.; Al-Saadi, M.A.K.; Jebur, I.O. Investigation the Immunoadjuvant Activity for Polysorbate 80. Asian J. Pharm. Nurs. Med. Sci. 2013, 1, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Del Giudice, G.; Rappuoli, R.; Didierlaurent, A.M. Correlates of Adjuvanticity: A Review on Adjuvants in Licensed Vaccines. Semin. Immunol. 2018, 39, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggio, E.T. Polysorbates, Immunogenicity, and the Totality of the Evidence. BioProcess Int. 2012, 10, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, K.R.; Evens, A.M.; Bennett, C.L.; Luminari, S. Clinical Characteristics of Erythropoietin-Associated Pure Red Cell Aplasia. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 2005, 18, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalobos, A.P.; Gunturi, S.R.; Heavner, G.A. Interaction of Polysorbate 80 with Erythropoietin: A Case Study in Protein–Surfactant Interactions. Pharm. Res. 2005, 22, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boven, K.; Stryker, S.; Knight, J.; Thomas, A.; Van Regenmortel, M.; Kemeny, D.; Power, D.; Rossert, J.; Casadevall, N. The Increased Incidence of Pure Red Cell Aplasia with Eprex Formulation in Uncoated Rubber Stopper Syringes. Kidney Int. 2005, 67, 2346–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlotte, H. Wrinkles Worries: Decoding Allergy Reactions to Botulinum Neurotoxin. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2025, 24, e70116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.C.; Pascal, A.B.; Halepas, S.; Koch, A. What Are the Most Commonly Reported Complications with Cosmetic Botulinum Toxin Type A Treatments? J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 78, e1–e1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, V.; Anatriello, A.; Cantone, A.; Nicoletti, M.M.; Argenziano, G.; Scavone, C.; Pieretti, G. The Use of Botulinum Toxin Type A and the Occurrence of Anaphylaxis: A Descriptive Analysis of Data from the European Spontaneous Reporting System. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2025, 49, 2032–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiu, I.; Geuna, M.; Heffler, E.; Rolla, G. Hypersensitivity Reaction to Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Due to Polysorbate 80. BMJ Case Rep. 2012, 2012, bcr0220125797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiszhár, Z.; Czúcz, J.; Révész, C.; Rosivall, L.; Szebeni, J.; Rozsnyay, Z. Complement Activation by Polyethoxylated Pharmaceutical Surfactants: Cremophor-EL, Tween-80 and Tween-20. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 45, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szebeni, J. Complement Activation-Related Pseudoallergy: A New Class of Drug-Induced Acute Immune Toxicity. Toxicology 2005, 216, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogozina, O.; Ruiz-Fernández, C.; Martín-López, S.; Akatbach-Bousaid, I.; González-Muñoz, M.; Ramírez, E. Organ-Specific Immune-Mediated Reactions to Polyethylene Glycol and Polysorbate Excipients: Three Case Reports. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 14, 1293294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, C.A.; Liu, Y.; Relling, M.V.; Krantz, M.S.; Pratt, A.L.; Abreo, A.; Hemler, J.A.; Phillips, E.J. Immediate Hypersensitivity to Polyethylene Glycols and Polysorbates: More Common Than We Have Recognized. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7, 1533–1540.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calogiuri, G.; Foti, C.; Nettis, E.; Di Leo, E.; Macchia, L.; Vacca, A. Polyethylene Glycols and Polysorbates: Two Still Neglected Ingredients Causing True IgE-Mediated Reactions. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7, 2509–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ieven, T.; Coorevits, L.; Vandebotermet, M.; Tuyls, S.; Vanneste, H.; Santy, L.; Wets, D.; Proost, P.; Frans, G.; Devolder, D.; et al. Endotyping of IgE-Mediated Polyethylene Glycol and/or Polysorbate 80 Allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2023, 11, 3146–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruusgaard-Mouritsen, M.A.; Johansen, J.D.; Garvey, L.H. Clinical Manifestations and Impact on Daily Life of Allergy to Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) in Ten Patients. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2021, 51, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neun, B.W.; Dobrovolskaia, M.A. Detection of Pre-Existing Antibodies to Polyethylene Glycol and PEGylated Liposomes in Human Serum. In Characterization of Nanoparticles Intended for Drug Delivery. Methods Mol. Bio 2024, 2789, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganson, N.J.; Povsic, T.J.; Sullenger, B.A.; Alexander, J.H.; Zelenkofske, S.L.; Sailstad, J.M.; Rusconi, C.P.; Hershfield, M.S. Pre-Existing Anti–Polyethylene Glycol Antibody Linked to First-Exposure Allergic Reactions to Pegnivacogin, a PEGylated RNA Aptamer. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 137, 1610–1613.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. Prescribing Information DAXXIFY/DaxibotulinumtoxinA-Lanm. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/761127s000lbl.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Electronic Medicines Compendium. Package Leaflet: Relfydess 100 Units/mL, Solution for Injection; Datapharm Ltd.: London, UK, 2025; Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/files/pil.100710.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Electronic Medicines Compendium. Package Leaflet: Alluzience 200 Speywood Units/mL, Solution for the Injection; Datapharm Ltd.: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/files/pil.13798.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Ascher, B.; Kestemont, P.; Boineau, D.; Bodokh, I.; Stein, A.; Heckmann, M.; Dendorfer, M.; Pavicic, T.; Volteau, M.; Tse, A.; et al. Liquid Formulation of AbobotulinumtoxinA Exhibits a Favourable Efficacy and Safety Profile in Moderate to Severe Glabellar Lines: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo- and Active Comparator-Controlled Trial. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2018, 38, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medytox. Botulinum Toxin Type A Product (Coretox®). Available online: https://www.medytox.com/page/coretox_en?site_id=en (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Medytox. Botulinum Toxin Type A Product (Innotox®). Available online: https://www.medytox.com/page/innotox_en?site_id=en (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Carruthers, A.; Carruthers, J.; Dover, J.S.; Alam, M.; Ibrahim, O. Procedures in Cosmetic Dermatology: Botulinum Toxin—E-Book; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers, J.D.; Fagien, S.; Joseph, J.H.; Humphrey, S.D.; Biesman, B.S.; Gallagher, C.J.; Liu, Y.; Rubio, R.G. DaxibotulinumtoxinA for Injection for the Treatment of Glabellar Lines: Results from Each of Two Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Studies (SAKURA 1 and SAKURA 2). Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2020, 145, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comella, C.L.; Jankovic, J.; Hauser, R.A.; Patel, A.T.; Banach, M.D.; Ehler, E.; Vitarella, D.; Rubio, R.G.; Gross, T.M.; on behalf of the ASPEN-1 Study Group; et al. Efficacy and Safety of DaxibotulinumtoxinA for Injection in Cervical Dystonia: ASPEN-1 Phase 3 Randomized Controlled Trial. Neurology 2024, 102, e208091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Multidiscipline Review: NDA 761127; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. 2011. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2022/761127Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- McAllister, P.; Patel, A.T.; Banach, M.; Ellenbogen, A.; Slawek, J.; Paus, S.; Jinnah, H.A.; Evidente, V.; Gross, T.M.; Kazerooni, R.; et al. Long-Term Safety and Efficacy of Repeat Treatments with DAXIBOTULINUMTOXINA in Cervical Dystonia: Results from the ASPEN -Open-Label Study. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2025, 12, 1764–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swissmedic, Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products. Swiss Public Assessment Report: Relfydess; Swissmedic: Bern, Switzerland, 2025. Available online: https://www.swissmedic.ch/dam/swissmedic/en/dokumente/zulassung/swisspar/69620-relfydess-01-swisspar-20250417.pdf.download.pdf/SwissPAR_Relfydess.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Kestemont, P.; Hilton, S.; Andriopoulos, B.; Prygova, I.; Thompson, C.; Volteau, M.; Ascher, B. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Liquid AbobotulinumtoxinA Formulation for Moderate-to-Severe Glabellar Lines: A Phase III, Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled and Open-Label Study. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2022, 42, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swedish Medical Products Agency. Public Assessment Report: Alluzience; Swedish MPA: Uppsala, Sweden, 2022. Available online: https://www.lakemedelsverket.se/sv/sok-lakemedelsfakta/lakemedel/20191122000079/alluzience-200-speywood-enheter-ml-injektionsvatska-losning (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Coleman, W.; Bertucci, V.; Humphrey, S.; Kaufman-Janette, J.; Keaney, T.; Pariser, D.; Solish, N.; Wirta, D.; Weiss, R.A. NivobotulinumtoxinA in the Treatment of Glabellar Lines with or Without Concurrent Treatment of Lateral Canthal Lines in Two Phase 3 Clinical Trials. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2025, 45, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, J.; DuBois, J.C.; Friedmann, D.P.; LaTowsky, B.; Palm, M.D.; Rivers, J.K.; Weinkle, S.H.; Duggan, S.; Enfield, K.; Donofrio, L.M. NivobotulinumToxinA in the Treatment of Lateral Canthal Lines Alone and with Concurrent Treatment of Glabellar Lines. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/dermatologicsurgery/fulltext/9900/nivobotulinumtoxina_in_the_treatment_of_lateral.1383.aspx (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Lee, J.; Chun, M.H.; Ko, Y.J.; Lee, S.-U.; Kim, D.Y.; Paik, N.-J.; Kwon, B.S.; Park, Y.G. Efficacy and Safety of MT10107 (Coretox) in Poststroke Upper Limb Spasticity Treatment: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Active Drug-Controlled, Multicenter, Phase III Clinical Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 1485–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Questions and Answers: Biological Medicinal Products—Polysorbate Testing in Finished Product Specification. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/research-and-development/scientific-guidelines/biological-guidelines/questions-answers-biological-medicinal-products#polysorbate-testing-in-finished-product-specification-32p5-32665 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Agilent Technologies. AdvanceBio Surfactant Profiling: A Robust LC/MS Workflow for Polysorbate Analysis; White Paper 5994-8110EN; Agilent Technologies: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.agilent.com/cs/library/whitepaper/public/wp-advancebio-surfactant-profiling-5994-8110en-agilent.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Aryal, B.; Lehtimaki, M.; Rao, A. Polysorbate 20 Degradation in Biotherapeutic Formulations and Its Impact on Protein Quality. In Proceedings of the FDA Science Forum, Online, 13–14 June 2023; Available online: https://www.fda.gov/science-research/fda-science-forum/polysorbate-20-degradation-biotherapeutic-formulations-and-its-impact-protein-quality (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Information for the Package Leaflet Regarding Polysorbates Used as Excipients in Medicinal Products for Human Use. EMA/CHMP/190743/2016. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/information-package-leaflet-regarding-polysorbates-used-excipients-medicinal-products-human-use_en.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Wuchner, K.; Yi, L.; Chery, C.; Nikels, F.; Junge, F.; Crotts, G.; Rinaldi, G.; Starkey, J.A.; Bechtold-Peters, K.; Shuman, M.; et al. Industry Perspective on the Use and Characterization of Polysorbates for Biopharmaceutical Products Part 1: Survey Report on Current State and Common Practices for Handling and Control of Polysorbates. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 111, 1280–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalrathnam, G.; Sharma, A.N.; Dodd, S.W.; Huang, L. Impact of Stainless Steel Exposure on the Oxidation of Polysorbate 80 in Histidine Placebo and Active Monoclonal Antibody Formulation. PDA J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 2018, 72, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovner, D.; Yuk, I.H.; Shen, A.; Li, H.; Graf, T.; Gupta, S.; Liu, W.; Tomlinson, A. Characterization of Recombinantly-Expressed Hydrolytic Enzymes from Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells: Identification of Host Cell Proteins That Degrade Polysorbate. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 112, 1351–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegues, M.A.; Szczepanek, K.; Sheikh, F.; Thacker, S.G.; Aryal, B.; Ghorab, M.K.; Wolfgang, S.; Donnelly, R.P.; Verthelyi, D.; Rao, V.A. Effect of Fatty Acid Composition in Polysorbate 80 on the Stability of Therapeutic Protein Formulations. Pharm. Res. 2021, 38, 1961–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.; Giovannini, R. Stability of Biologics and the Quest for Polysorbate Alternatives. Trends Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 546–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Chandra, D.; Letarte, S.; Adam, G.C.; Welch, J.; Yang, R.-S.; Rivera, S.; Bodea, S.; Dow, A.; Chi, A.; et al. Profiling Active Enzymes for Polysorbate Degradation in Biotherapeutics by Activity-Based Protein Profiling. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 8161–8169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiß, L.; Zeh, N.; Maier, M.; Lakatos, D.; Otte, K.; Fischer, S. Without a Trace: Multiple Knockout of CHO Host Cell Hydrolases to Prevent Polysorbate Degradation in Biologics. Trends Biotechnol. 2025, 43, 1982–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhargava, A.C.; Mains, K.; Siu, A.; Gu, J.; Zarzar, J.; Yi, L.; Yuk, I.H. High-Throughput, Fluorescence-Based Esterase Activity Assay for Assessing Polysorbate Degradation Risk during Biopharmaceutical Development. Pharm. Res. 2021, 38, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.Y.; Kim, B.J.; Lee, Y.W.; Kim, W.; Yoon, Y.N.; Kim, J.S. Efficacy and Safety of CKDB-501A in Treating Moderate-To-Severe Glabellar Lines: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Active-Controlled, Multi-Center Phase III Trial. J. Cosmet. Dermatol 2025, 24, e70305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CKD Bio. Botulinum Toxin Type A (Tyemvers®). Available online: https://www.ckdbio.com/en/home (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Soeda, K.; Fukuda, M.; Takahashi, M.; Imai, H.; Arai, K.; Saitoh, S.; Kishore, R.S.K.; Oltra, N.S.; Duboeuf, J.; Hashimoto, D.; et al. Impact of Poloxamer 188 Material Attributes on Proteinaceous Visible Particle Formation in Liquid Monoclonal Antibody Formulations. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 111, 2191–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollenbach, L.; Buske, J.; Mäder, K.; Garidel, P. Poloxamer 188 as Surfactant in Biological Formulations—An Alternative for Polysorbate 20/80? Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 620, 121706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Markham, A.; Thomas, S.J.; Wang, N.; Huang, L.; Clemens, M.; Rajagopalan, N. Solution Stability of Poloxamer 188 Under Stress Conditions. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 108, 1264–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.L.; Wilkes, M.M.; Navickis, R.J. Safety of Human Albumin: Serious Adverse Events Reported Worldwide in 1998-2000. Surv Anesthesiol. 2004, 48, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Immunogenicity |

IgE-Mediated

Hypersensitivity |

Non-IgE Mediated

Hypersensitivity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical presentations | Loss of efficacy over time (secondary nonresponse) | Hypersensitivity symptoms such as itching, swelling, urticaria | |

| Time to onset | Activation of antigen-presenting cell complex within hours and adaptive immune system over days/weeks. Clinical manifestation of secondary nonresponse may occur months or years later. | Immediate (seconds to a few hours) upon exposure | |

| Detection methods |

|

|

|

|

| ||

| Product Name | Generic Name or Code Name | Initial Approval (Year) | Form | Polysorbate Excipient Content | Storage Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAXXIFY® [51] | DaxibotulinumtoxinA | United States (2022) | Lyophilized powder | PS20 (0.1 mg per 50 U or 100 U vial) | At RT, protected from light. |

| Relfydess® [52] | RelabotulinumtoxinA | Europe (2022) | Liquid, ready-to-use | PS80 (1.6 mg per 150 U vial, or 1.1 mg/mL) | At 2 °C to 8 °C. Unopened vial may be brought to RT at 25 °C while protected from light. Stability for unopened vials has been demonstrated up to 24 h at RT. |

| Alluzience® [53,54] | AbobotulinumtoxinA RTU | Europe (2021) | Liquid, ready-to-use | PS80 (0.1 mg per 1 mL, 500 U vial) | At 2 °C to 8 °C. May be held at up to maximum of 25 °C for a single period of 12 h when unopened and protected from light. |

| Coretox® [2,55] | MT10107 | South Korea (2016) | Lyophilized powder | PS20 (1.0 mg per 100 U vial) | At 2 °C to 8 °C in hermetic container. |

| Innotox® [56,57] | NivobotulinumtoxinA | South Korea (2013) | Liquid, ready-to-use | PS20 (0.094 mg per 50 U or 100 U vial) | At 2 °C to 8 °C in hermetic container. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martin, M.U.; Frevert, J.; Park, J.-Y.; Cui, H.; Curry, A.; Loh, W.Q. Immunological Considerations of Polysorbate as an Excipient in Botulinum Neurotoxin Type A Formulations: A Narrative Review. Toxins 2025, 17, 598. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120598

Martin MU, Frevert J, Park J-Y, Cui H, Curry A, Loh WQ. Immunological Considerations of Polysorbate as an Excipient in Botulinum Neurotoxin Type A Formulations: A Narrative Review. Toxins. 2025; 17(12):598. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120598

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartin, Michael Uwe, Jürgen Frevert, Je-Young Park, Haiyan Cui, Andy Curry, and Wei Qi Loh. 2025. "Immunological Considerations of Polysorbate as an Excipient in Botulinum Neurotoxin Type A Formulations: A Narrative Review" Toxins 17, no. 12: 598. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120598

APA StyleMartin, M. U., Frevert, J., Park, J.-Y., Cui, H., Curry, A., & Loh, W. Q. (2025). Immunological Considerations of Polysorbate as an Excipient in Botulinum Neurotoxin Type A Formulations: A Narrative Review. Toxins, 17(12), 598. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120598