Mycotoxin-Induced Oxidative Stress and Its Impact on Human Folliculogenesis: Examining the Link to Reproductive Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

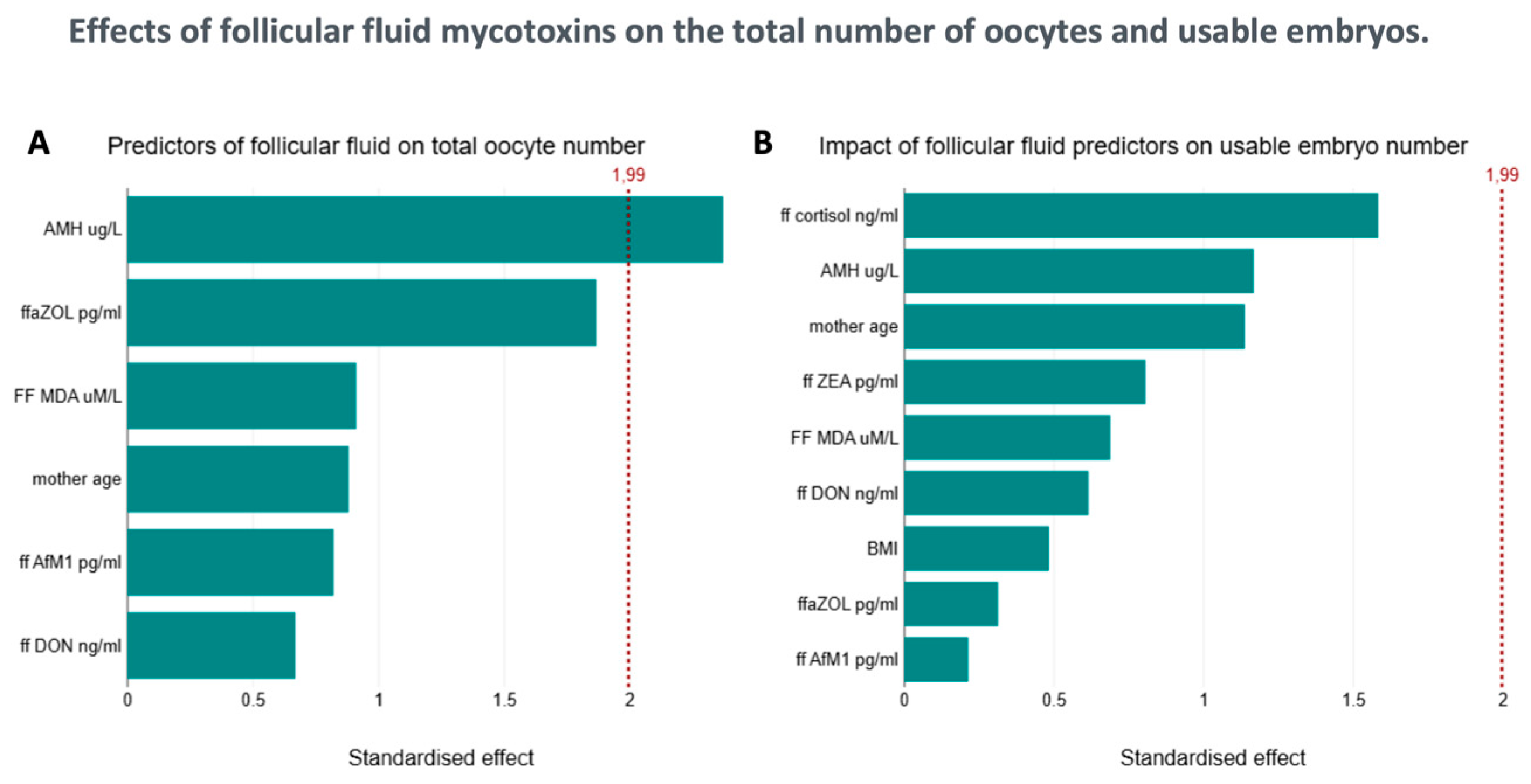

2.1. Biophysical Parameters and Mycotoxin Levels in the Context of Follicle Number

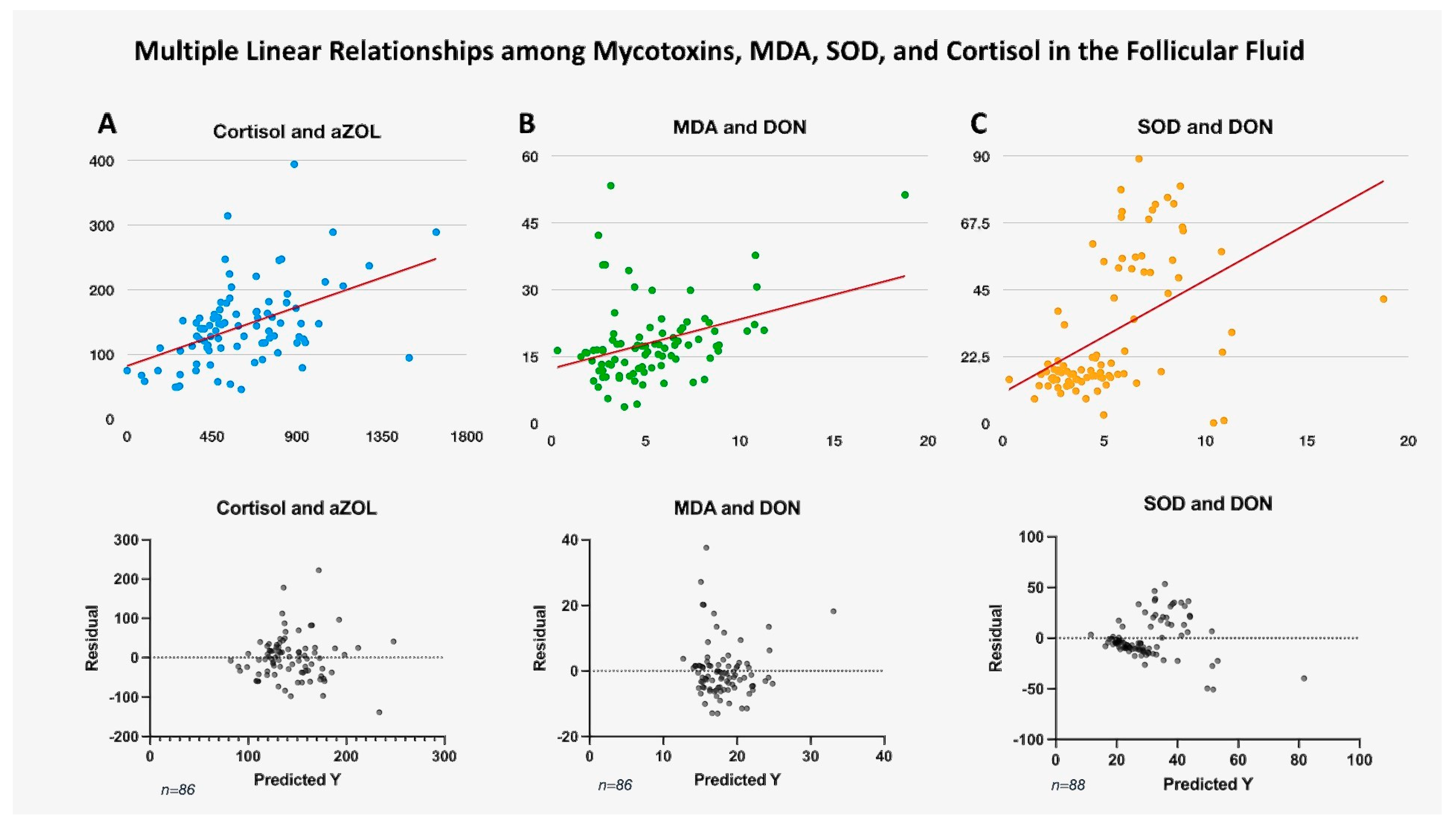

2.2. Follicular Fluid MDA Levels

2.3. Serum and Follicular Fluid Cortisol Levels

2.4. Follicular Fluid SOD Levels

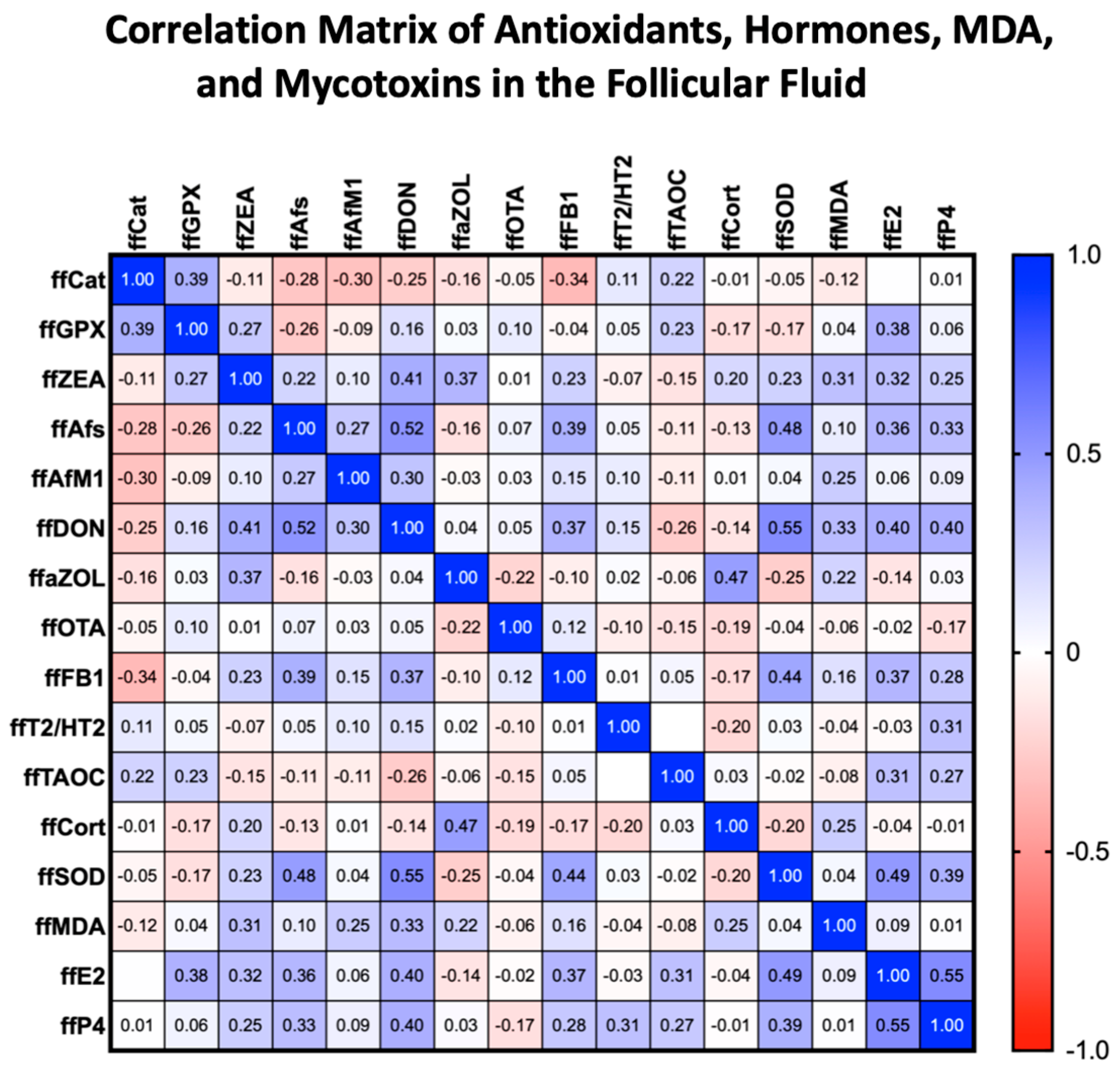

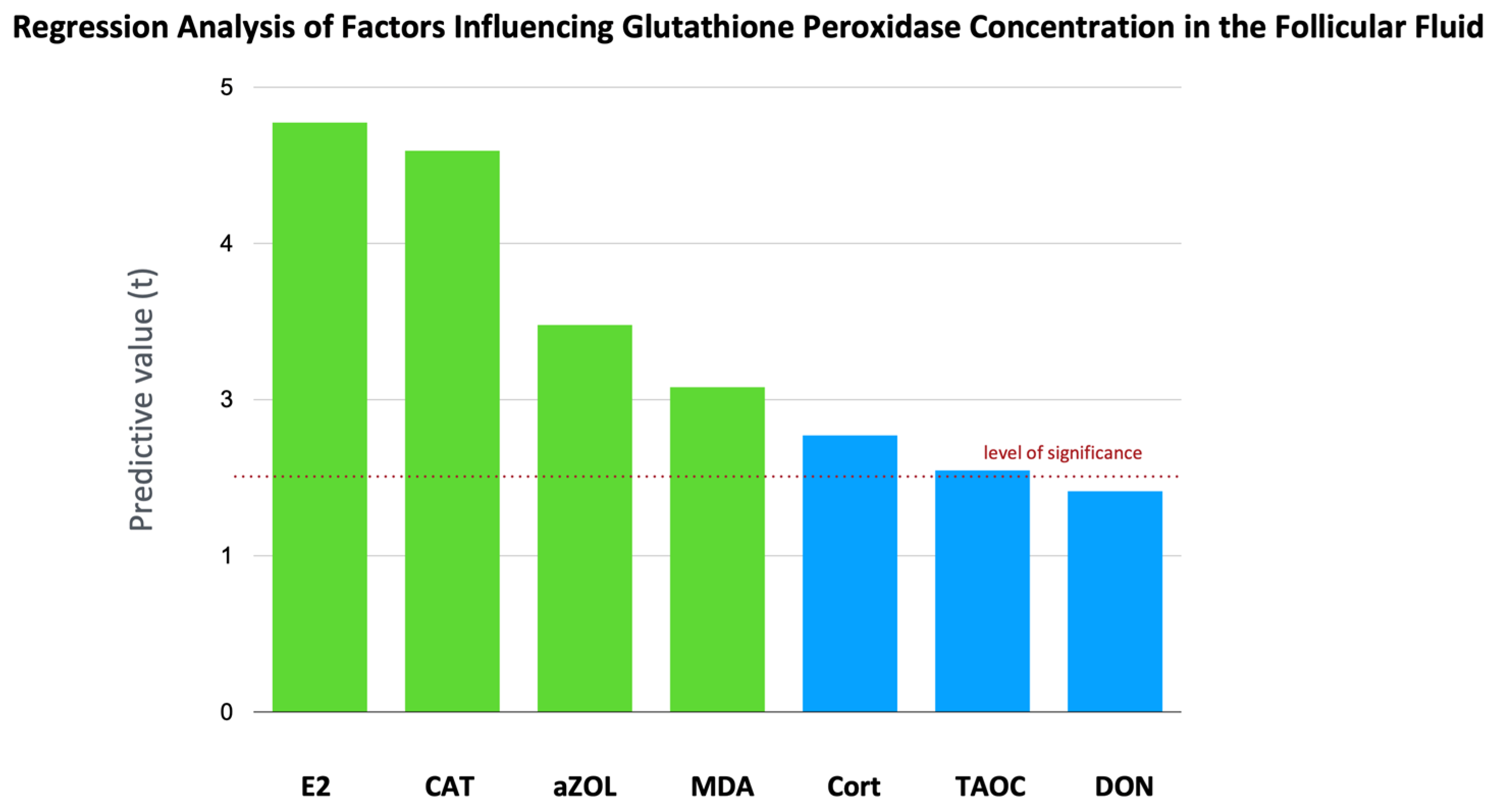

2.5. Total Antioxidant Capacity, CAT Activity, and GPx Activity

3. Discussion

3.1. The Link with Oxidative Stress

3.2. The Antioxidant Counterbalances

3.3. Endocrine Disruptor Effects

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Patients

5.2. Mycotoxin Analyses

5.3. Steroid Analyses

5.4. Serum Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH) Measurements

5.5. FF Protein Measurements by Nanodrop

5.6. SOD Analysis in Follicular Fluid

5.7. Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) Activity Assay

5.8. Catalase Activity Assay

5.9. FF MDA Assay

5.10. Total Antioxidant Capacity (T-AOC) Assay

5.11. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DON | Deoxynivalenol |

| ZEN | Zearalenone |

| aZOL | Alpha-zearalenol |

| AfM1 | Aflatoxin M1 |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| TAOC | Total antioxidant capacity |

| AMH | Anti-Müllerian hormone |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| OTA | Ochratoxin A |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| AFs | Aflatoxins |

| FB1 | Fumonisin B1 |

| AOH | Alternariol |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| IVF | In vitro fertilization |

| E2 | Estradiol |

| P4 | Progesterone |

| FSH | Follicle-stimulating hormone |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

References

- Kos, J.; Anić, M.; Radić, B.; Zadravec, M.; Janić Hajnal, E.; Pleadin, J. Climate Change—A Global Threat Resulting in Increasing Mycotoxin Occurrence. Foods 2023, 12, 2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unicsovics, M.; Molnár, Z.; Mézes, M.; Posta, K.; Nagyéri, G.; Várbíró, S.; Ács, N.; Sára, L.; Szőke, Z. The Possible Role of Mycotoxins in the Pathogenesis of Endometrial Cancer. Toxins 2024, 16, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakatos, I.; Babarczi, B.; Molnár, Z.; Tóth, A.; Skoda, G.; Horváth, G.F.; Horváth, A.; Tóth, D.; Sükösd, F.; Szemethy, L.; et al. First Results on the Presence of Mycotoxins in the Liver of Pregnant Fallow Deer (Dama dama) Hinds and Fetuses. Animals 2024, 14, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Infertility Prevalence Estimates: 1990–2021; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Romualdi, D.; Ata, B.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bosch, E.; Costello, M.; Gersak, K.; Homburg, R.; Mincheva, M.; Norman, R.J.; Piltonen, T.; et al. Evidence-based guideline: Unexplained infertility. Hum. Reprod. 2023, 38, 1881–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szentirmay, A.; Molnár, Z.; Plank, P.; Mézes, M.; Sajgó, A.; Martonos, A.; Buzder, T.; Sipos, M.; Hruby, L.; Szőke, Z.; et al. The Potential Influence of the Presence of Mycotoxins in Human Follicular Fluid on Reproductive Outcomes. Toxins 2024, 16, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpsoy, L.; Yildirim, A.; Agar, G. The antioxidant effects of vitamin A, C, and E on aflatoxin B-1-induced oxidative stress in human lymphocytes. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2009, 25, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriszt, R.; Winkler, Z.; Polyák, Á.; Kuti, D.; Molnár, C.; Hrabovszky, E.; Kalló, I.; Szőke, Z.; Ferenczi, S.; Kovács, K.J. Xenoestrogens Ethinyl Estradiol and Zearalenone Cause Precocious Puberty in Female Rats via Central Kisspeptin Signaling. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 3996–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulcsár, S.; Kövesi, B.; Balogh, K.; Zándoki, E.; Ancsin, Z.; Erdélyi, M.; Mézes, M. The Co-Occurrence of T-2 Toxin, Deoxynivalenol, and Fumonisin B1 Activated the Glutathione Redox System in the EU-Limiting Doses in Laying Hens. Toxins 2023, 15, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulcsár, S.; Kövesi, B.; Balogh, K.; Zándoki, E.; Ancsin, Z.; Márta, B.E.; Mézes, M. Effects of Fusarium Mycotoxin Exposure on Lipid Peroxidation and Glutathione Redox System in the Liver of Laying Hens. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wen, J.; Tang, Y.; Shi, J.; Mu, G.; Yan, R.; Cai, J.; Long, M. Research Progress on Fumonisin B1 Contamination and Toxicity: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 5238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, S.; Cheng, L.; Man, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhao, H. Oxidative stress markers in the follicular fluid of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome correlate with a decrease in embryo quality. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2021, 38, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.; Bracarense, A.P.; Oswald, I. Mycotoxins and oxidative stress: Where are we? World Mycotoxin J. 2018, 11, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, C.F.; Baldissera, M.D.; Descovi, S.N.; Zeppenfeld, C.C.; Garzon, L.R.; Da Silva, A.S.; Stefani, L.M.; Baldisserotto, B. Serum and hepatic oxidative damage induced by a diet contaminated with fungal mycotoxin in freshwater silver catfish Rhamdia quelen: Involvement on disease pathogenesis. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 124, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, L. The Impact of Follicular Fluid Oxidative Stress Levels on the Outcomes of Assisted Reproductive Therapy. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minervini, F.; Giannoccaro, A.; Fornelli, F.; Dell’Aquila, M.E.; Minoia, P.; Visconti, A. Influence of mycotoxin zearalenone and its derivatives (alpha and beta zearalenol) on apoptosis and proliferation of cultured granulosa cells from equine ovaries. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2006, 4, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.-L.; Wu, R.-Y.; Sun, X.-F.; Cheng, S.-F.; Zhang, R.-Q.; Zhang, T.-Y.; Zhang, X.-F.; Zhao, Y.; Shen, W.; Li, L. Mycotoxin zearalenone exposure impairs genomic stability of swine follicular granulosa cells in vitro. Int. J. Biol. Sci 2018, 14, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecomte, S.; Demay, F.; Pham, T.H.; Moulis, S.; Efstathiou, T.; Chalmel, F.; Pakdel, F. Deciphering the Molecular Mechanisms Sustaining the Estrogenic Activity of the Two Major Dietary Compounds Zearalenone and Apigenin in ER-Positive Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Nutrients 2019, 11, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pogrmic-Majkic, K.; Samardzija Nenadov, D.; Stanic, B.; Milatovic, S.; Trninic-Pjevic, A.; Kopitovic, V.; Andric, N. T-2 toxin downregulates LHCGR expression, steroidogenesis, and cAMP level in human cumulus granulosa cells. Environ. Toxicol. 2019, 34, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.J.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Xiong, B.; Cui, X.S.; Kim, N.H.; Xu, Y.X.; Sun, S.C. Mycotoxin-containing diet causes oxidative stress in the mouse. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelko, I.N.; Mariani, T.J.; Folz, R.J. Superoxide dismutase multigene family: A comparison of the CuZn-SOD (SOD1), Mn-SOD (SOD2), and EC-SOD (SOD3) gene structures, evolution, and expression. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 33, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, L.; Wilson, C.; Lower, A.; Al-Shawaf, T.; Grudzinskas, J.G. Superoxide dismutase activity in human follicular fluid after controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. Fertil. Steril. 1999, 72, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiotani, M.; Noda, Y.; Narimoto, K.; Imai, K.; Takahide, M.; Fujimoto, K.; Ogawa, K. Immunohistochemical localization of superoxide dismutase in the human ovary. Hum. Reprod. 1991, 6, 1349–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fateh, M.; Ben-Rafael, Z.; Benadiva, C.A.; Mastroianni, L.; Flickinger, G.L. Cortisol levels in human follicular fluid. Fertil. Steril. 1989, 51, 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, N.; Inal, H.A.; Gorkem, U.; Sargin Oruc, A.; Yilmaz, S.; Turkkani, A. Follicular fluid total antioxidant capacity levels in PCOS. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 36, 654–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannubilo, S.; Orlando, P.; Silvestri, S.; Cirilli, I.; Marcheggiani, F.; Ciavattini, A.; Tiano, L. CoQ10 Supplementation in Patients Undergoing IVF-ET: The Relationship with Follicular Fluid Content and Oocyte Maturity. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luddi, A.; Governini, L.; Capaldo, A.; Campanella, G.; De Leo, V.; Piomboni, P.; Morgante, G. Characterization of the Age-Dependent Changes in Antioxidant Defenses and Protein’s Sulfhydryl/Carbonyl Stress in Human Follicular Fluid. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabó-Fodor, J.; Szabó, A.; Kócsó, D.; Marosi, K.; Bóta, B.; Kachlek, M.; Mézes, M.; Balogh, K.; Kövér, G.; Nagy, I.; et al. Interaction between the three frequently co-occurring Fusarium mycotoxins in rats. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2019, 103, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaji, H.; Kurasaki, M.; Ito, K.; Saito, T.; Saito, K.; Niioka, T.; Kojima, Y.; Ohsaki, Y.; Ide, H.; Tsuji, M.; et al. Increased lipoperoxide value and glutathione peroxidase activity in blood plasma of Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetic women. Klin. Wochenschr. 1985, 63, 765–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Blanco, C.; Font, G.; Ruiz, M.-J. Oxidative DNA damage and disturbance of antioxidant capacity by alternariol in Caco-2 cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2015, 235, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangari, N.; O’Brien, P.J. Catalase Activity Assays. Curr. Protoc. Toxicol. 2006, 27, 7.7.1–7.7.16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, R.R.M.; Lima, N. Toxicology of mycotoxins. In Molecular, Clinical and Environmental Toxicology: Volume 2: Clinical Toxicology; Luch, A., Ed.; Birkhäuser Basel: Basel, Switzerland, 2010; pp. 31–63. [Google Scholar]

- Imran, M.; Cao, S.; Wan, S.; Chen, Z.; Saleemi, M.K.; Wang, N.; Naseem, M.N.; Munawar, J. Mycotoxins—A global one health concern: A review. Agrobiol. Rec. 2020, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, J.; Kersten, S.; Meyer, U.; Stinshoff, H.; Locher, L.; Rehage, J.; Wrenzycki, C.; Engelhardt, U.H.; Dänicke, S. Diagnostic opportunities for evaluation of the exposure of dairy cows to the mycotoxins deoxynivalenol (DON) and zearalenone (ZEN): Reliability of blood plasma, bile and follicular fluid as indicators. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2015, 99, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, M.; Mukai, S.; Kuriyagawa, T.; Takagaki, K.; Uno, S.; Kokushi, E.; Otoi, T.; Budiyanto, A.; Shirasuna, K.; Miyamoto, A.; et al. Detection of zearalenone and its metabolites in naturally contaminated follicular fluids by using LC/MS/MS and in vitro effects of zearalenone on oocyte maturation in cattle. Reprod. Toxicol. 2008, 26, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, A.; Ramezanzadeh, F.; Esfahani, M.H.N.; Saboor-Yaraghi, A.A.; Nejat, S.N.; Rahimi-Foroshani, A. Relationship between Energy Expenditure Related Factors and Oxidative Stress in Follicular Fluid. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 8, 175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yuksel, B.; Kilic, S.; Yilmaz, N.; Goktas, T.; Keskin, U.; Seven, A.; Ulubay, M.; Batioglu, S.; Yuksel, B.; Kilic, S.; et al. Obesity is not a descriptive factor for oxidative stress and viscosity in follicular fluid of in vitro fertilization patients. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 186, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale-Fernandes, E.; Moreira, M.V.; Rodrigues, B.; Pereira, S.S.; Leal, C.; Barreiro, M.; Tomé, A.; Monteiro, M.P. Anti-Müllerian hormone a surrogate of follicular fluid oxidative stress in polycystic ovary syndrome? Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1408879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotanidis, L.; Nikolettos, K.; Petousis, S.; Asimakopoulos, B.; Chatzimitrou, E.; Kolios, G.; Nikolettos, N. The use of serum anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) levels and antral follicle count (AFC) to predict the number of oocytes collected and availability of embryos for cryopreservation in IVF. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2016, 39, 1459–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardo, L.G.; Christodoulou, D.; Gould, D.; Roberts, S.A.; Fitzgerald, C.T.; Laing, I. Anti-Müllerian hormone levels and antral follicle count in women enrolled inin vitrofertilization cycles: Relationship to lifestyle factors, chronological age and reproductive history. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2007, 23, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessow, C.; Donato, R.; De Souza, T.; Chapon, R.; Genro, V.; Cunha-Filho, J.S. Antral follicle responsiveness assessed by follicular output RaTe(FORT) correlates with follicles diameter. J. Ovarian Res. 2019, 12, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, B.; Huang, L.; Jing, C.; Li, Y.; Jiao, N.; Liang, M.; Jiang, S.; Yang, W. Zearalenone promotes follicle development through activating the SIRT1/PGC-1α signaling pathway in the ovaries of weaned gilts. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100, skac058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Marca, A.; Grisendi, V.; Griesinger, G. How Much Does AMH Really Vary in Normal Women? Int. J. Endocrinol. 2013, 2013, 959487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weenen, C.; Laven, J.S.E.; von Bergh, A.R.M.; Cranfield, M.; Groome, N.P.; Visser, J.A.; Kramer, P.; Fauser, B.C.J.M.; Themmen, A.P.N. Anti-Müllerian hormone expression pattern in the human ovary: Potential implications for initial and cyclic follicle recruitment. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2004, 10, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zec, I.; Tislaric-Medenjak, D.; Bukovec Megla, Z.; Kucak, I. Anti-Müllerian hormone: A unique biochemical marker of gonadal development and fertility in humans. Biochem. Med. 2011, 21, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Lim, W.; Park, S.; Kim, J.; You, S.; Song, G. Deoxynivalenol induces apoptosis and disrupts cellular homeostasis through MAPK signaling pathways in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouault, M.; Delalande, C.; Bouraïma-Lelong, H.; Seguin, V.; Garon, D.; Hanoux, V. Deoxynivalenol enhances estrogen receptor alpha-induced signaling by ligand-independent transactivation. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 165, 113127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikas, D. Assessment of lipid peroxidation by measuring malondialdehyde (MDA) and relatives in biological samples: Analytical and biological challenges. Anal. Biochem. 2017, 524, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Xu, W.; Yang, F.; Wei, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Lv, Q.; Xu, W.; Yang, F.; et al. Reproductive Toxicity of Zearalenone and Its Molecular Mechanisms: A Review. Molecules 2025, 30, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, A.; Aponte-Mellado, A.; Premkumar, B.J.; Shaman, A.; Gupta, S. The effects of oxidative stress on female reproduction: A review. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2012, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May-Panloup, P.; Boucret, L.; Chao De La Barca, J.-M.; Desquiret-Dumas, V.; Ferré-L’Hotellier, V.; Morinière, C.; Descamps, P.; Procaccio, V.; Reynier, P. Ovarian ageing: The role of mitochondria in oocytes and follicles. Hum. Reprod. Update 2016, 22, 725–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuć-Szymanek, A.; Kubik-Machura, D.; Kościelecka, K.; Męcik-Kronenberg, T.; Radko, L. Neurotoxicological Effects of Some Mycotoxins on Humans Health and Methods of Neuroprotection. Toxins 2025, 17, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-H.; Wang, J.-H.; Guo, W.-B.; Ling, A.R.; Luo, A.-Q.; Liu, D.; Yang, X.-L.; Zhao, Z.-H. Toxic Effects and Possible Mechanisms of Deoxynivalenol Exposure on Sperm and Testicular Damage in BALB/c Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 2289–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yan, G.; Chang, J.; Wang, P.; Yin, Q.; Liu, C.; Liu, S.; Zhu, Q.; Lu, F. Astilbin ameliorates deoxynivalenol-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in intestinal porcine epithelial cells (IPEC-J2). J. Appl. Toxicol. 2020, 40, 1362–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Zhang, J.; Lai, Z.; Tian, Y.; Fang, L.; Wu, M.; Xiong, J.; Qin, X.; Luo, A.; Wang, S. Long-Term Moderate Oxidative Stress Decreased Ovarian Reproductive Function by Reducing Follicle Quality and Progesterone Production. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, C. Possible new mechanism of cortisol action in female reproductive organs: Physiological implications of the free hormone hypothesis. J. Endocrinol. 2002, 173, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boisseau, N.; Enea, C.; Diaz, V.; Dugue, B.; Corcuff, J.-B.; Duclos, M. Oral contraception but not menstrual cycle phase is associated with increased free cortisol levels and low HPA axis reactivity. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2013, 36, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannsen, M.L.; Poulsen, L.C.; Mamsen, L.S.; Grøndahl, M.L.; Englund, A.L.M.; Lauritsen, N.L.; Carstensen, E.C.; Styrishave, B.; Yding Andersen, C. The intrafollicular concentrations of biologically active cortisol in women rise abruptly shortly before ovulation and follicular rupture. Hum. Reprod. 2024, 39, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquardt, R.M.; Kim, T.H.; Shin, J.-H.; Jeong, J.-W. Progesterone and Estrogen Signaling in the Endometrium: What Goes Wrong in Endometriosis? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Van Sinderen, M.; Rainczuk, K.; Menkhorst, E.; Sorby, K.; Osianlis, T.; Pangestu, M.; Santos, L.; Rombauts, L.; Rosello-Diez, A.; et al. Dysregulated miR-124-3p in endometrial epithelial cells reduces endometrial receptivity by altering polarity and adhesion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2401071121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Qin, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Yan, Q. N-glycosylation of uterine endometrium determines its receptivity. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 1076–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehorai, E.; Gross Lev, T.; Shimshoni, E.; Hadas, R.; Adir, I.; Golani, O.; Molodij, G.; Eitan, R.; Kadler, K.E.; Kollet, O.; et al. Enhancing uterine receptivity for embryo implantation through controlled collagenase intervention. Life Sci. Alliance 2024, 7, e202402656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowska, A.; Pomastowski, P.; Sagandykova, G.; Buszewski, B. Zearalenone and its metabolites: Effect on human health, metabolism and neutralisation methods. Toxicon 2019, 162, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari-Nodoushan, A.A. Zearalenone, an abandoned mycoestrogen toxin, and its possible role in human infertility. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2022, 20, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Median | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 36.44 | 4.276 | 37.0 | 28 | 44 |

| BMI | 24.62 | 4.498 | 23.8 | 17.6 | 37.7 |

| Anti-Mullerian Hormone (μg/L) | 2.092 | 1.999 | 1.450 | 0.15 | 8.53 |

| Total number of Follicles (n) | 10.5 | 5.543 | 10 | 2 | 27 |

| Dominant Follicles (⊘ > 15 mm, n) | 7.641 | 4.385 | 7 | 1 | 21 |

| Useable Embryos (n) | 1.942 | 1.929 | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| Ratio of oocytes/all follicles | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.4 | 0 | 1.17 |

| Ratio of embryos/all follicles | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0 | 0.6 |

| Ratio of embryos/dominant follicles | 0.18 | 0.2 | 0.13 | 0 | 0.9 |

| Serum P4 (μg/L) | 1.438 † | 0.9248 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 5.1 |

| Ff P4 (μg/L) | 6846 ✴,† | 2144 | 6274 | 1500 | 12,966 |

| Serum E2 5.day (pg/ml) | 48.01 | 17.92 | 48.0 | 17.1 | 84.7 |

| Serum E2 12.day (pg/ml) | 1811 | 1207 | 1504 | 295 | 4575 |

| Ff E2 (pg/ml) | 48,101 ✴︎ | 13,720 | 46,460 | 26,861 | 108,050 |

| FSH (IU/L) | 6.401 | 3.087 | 6.1 | 0.8 | 17.0 |

| LH (IU/L) | 5.833 | 2.747 | 5.3 | 1.2 | 14.4 |

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Median | Median in nM | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| serum Aflatoxin (pg/ml) | 1.364 | 7.423 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 47 |

| Ff Aflatoxin (pg/ml) | 27.92 | 73.31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 432.7 |

| serum Aflatoxin M1 (pg/ml) | 11.5 † | 19.59 | 5.258 | 1.68 × 10−5 | 0 | 133.5 |

| Ff Aflatoxin M1 (pg/ml) | 11.49 † | 18.14 | 6.12 | 1.86 × 10−5 | 0 | 114.1 |

| serum Zearalenone (pg/ml) | 66.18 | 78.38 | 44.44 | 1.39 × 10−4 | 0 | 391.19 |

| Ff Zearalenone (pg/ml) | 155.5 ✴︎ | 239.2 | 99.1 | 3.11 × 10−4 | 0 | 1744 |

| serum alpha-Zearalenol (pg/ml) | 129.5 † | 105.9 | 107 | 3.33 × 10−4 | 0 | 438 |

| Ff alpha-Zearalenol (pg/ml) | 605.4 ✴,† | 290.9 | 543.1 | 1.69 × 10−3 | 0 | 1637 |

| serum Ochratoxin A (pg/ml) | 9.659 | 9.189 | 8 | 1.98 × 10−5 | 0 | 60 |

| Ff Ochratoxin A (pg/ml) | 9.62 | 8.84 | 6 | 1.48 × 10−5 | 0 | 37.33 |

| serum Fumonisin B1 (pg/ml) | 70.84 † | 99.78 | 24.4 | 3.38 × 10−4 | 0 | 388.4 |

| Ff Fumonisin B1 (pg/ml) | 53.37 ✴,† | 86.26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 405.3 |

| serum Deoxynivalenol (ng/ml) | 3.47 | 2.98 | 2.69 | 9.07 × 10−3 | 0 | 19.35 |

| Ff Deoxynivalenol (ng/ml) | 5.26 ✴︎ | 2.82 | 4.80 | 1.61 × 10−2 | 0.31 | 18.77 |

| serum T2/HT2 toxin (ng/ml) | 1.90 † | 1.145 | 2.13 | 4.56 × 10−3 | 0 | 4.25 |

| Ff T2/HT2 toxin (ng/ml) | 1.86 † | 1.39 | 1.88 | 4.02 × 10−4 | 0 | 7.82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szőke, Z.; Ruff, E.; Plank, P.; Molnár, Z.; Hruby, L.; Szentirmay, A.; Unicsovics, M.; Csókay, B.; Varga, K.; Buzder, T.; et al. Mycotoxin-Induced Oxidative Stress and Its Impact on Human Folliculogenesis: Examining the Link to Reproductive Health. Toxins 2025, 17, 574. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120574

Szőke Z, Ruff E, Plank P, Molnár Z, Hruby L, Szentirmay A, Unicsovics M, Csókay B, Varga K, Buzder T, et al. Mycotoxin-Induced Oxidative Stress and Its Impact on Human Folliculogenesis: Examining the Link to Reproductive Health. Toxins. 2025; 17(12):574. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120574

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzőke, Zsuzsanna, Eszter Ruff, Patrik Plank, Zsófia Molnár, Lili Hruby, Apolka Szentirmay, Márkó Unicsovics, Bernadett Csókay, Katalin Varga, Tímea Buzder, and et al. 2025. "Mycotoxin-Induced Oxidative Stress and Its Impact on Human Folliculogenesis: Examining the Link to Reproductive Health" Toxins 17, no. 12: 574. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120574

APA StyleSzőke, Z., Ruff, E., Plank, P., Molnár, Z., Hruby, L., Szentirmay, A., Unicsovics, M., Csókay, B., Varga, K., Buzder, T., Sipos, M., Sára-Popovics, K., Holéci, D., Posta, K., & Sára, L. (2025). Mycotoxin-Induced Oxidative Stress and Its Impact on Human Folliculogenesis: Examining the Link to Reproductive Health. Toxins, 17(12), 574. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120574