1. Introduction

When maize is infected by the

Fusarium species, it will not only reduce the yield and quality, but also result in the accumulation of toxic mycotoxins. Mycotoxins are synthesized in maize kernels and accumulate in maize-based feed directly [

1,

2]. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimated that more than 25% of cereal crops are lost annually due to mycotoxin contamination [

3]. In addition, mycotoxins can enter humans and animals through the food chain, which is a serious threat to human and animal health and causes heavy economic losses [

4,

5].

Fumonisin is a group of highly toxic low molecular weight mycotoxins, primarily produced by

Fusarium verticillioides and

Fusarium proliferatum that have been widely found to be contaminants worldwide [

6,

7]. To date, 28 chemical structures of fumonisin have been discovered. Among them, fumonisin B1 (FB1), fumonisin B2 (FB2) and fumonisin B3 (FB3) are the three main forms [

8]. Fumonisin can be transformed into modified fumonisin, such as hydrolyzed fumonisin, after being metabolized by microorganisms or plants and even the grinding of grain samples. A survey of mycotoxin contamination of 4 batches of 327 grain samples worldwide showed that the positive rates of major fumonisin were approximately 58% (Africa), 51% (Central Europe), 27% (North America), 51% (Central Europe), 56% (South Asia) and 55% (Southeast Asia) in different areas [

9]. Fumonisin mainly contaminate maize and maize products.

FB1 is the most polluted and toxic fumonisin. Studies have shown many adverse effects of fumonisin, including liver and kidney toxicity, enterotoxicity, immunosuppressive effects, neurodevelopmental toxicity, neonatal neural tube defects, and esophageal and liver cancer [

10,

11,

12,

13]. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IRAC) listed fumonisin as a 2B carcinogen in 2002 [

1]. However, multiple fumonisins are often found at the same time in the same environment. If only the toxicity of a single fumonisin is considered, and the interactions between mixtures (additive or synergistic or antagonistic effect) are ignored, the true toxicity of fumonisins cannot be accurately reflected in the actual environment [

8,

14]. Moreover, hydrolyzed fumonisin B1 (HFB1) was mentioned to competitively inhibit the enzyme ceramide synthase and to generate acetylated products [

15]. However, the metabolism and toxicity mechanisms of modified fumonisin in animals have rarely been researched.

With its inherent advantages of high efficiency and low cost, the broiler breeding industry achieved a historical highest degree of industrialization in animal husbandry in China. Broiler production in China has increased from 1.358 million tons in 1984 to 11.44 million tons in 2009, and continues to grow at a rate of 5–10% per year. The Pudong Sanhuang broiler is a breed that is characteristic as one of the important economic animals in China with the advantages of a short growth cycle, strong disease resistance and rich nutritional value [

16]. Most poultry broiler (early stage) feeds are severely contaminated by fumonisin. The contaminant rate of fumonisin B pollutants in compound feed and feed ingredients was 93.33% and 83.33%, respectively, and the highest feed detection level at 12.82 mg/kg was found in Korea in published papers [

17]. In 2019, a survey of fumonisin contamination in maize feed in China showed that feed was not only contaminated by the parent fumonisin, but also approximately 71.23% of the samples were contaminated by modified fumonisin [

3].

Based on this, this study used broiler chickens as an in vivo research model to explore the hazards of fumonisin Bs (FBs) and its modified forms to poultry. By using feed naturally contaminated with different levels of FBs (FB1, FB2 and FB3) or modified forms (without detectable levels of other mycotoxins), the effects of FBs on animal growth, blood biochemistry and intestinal microbiota can be observed. This study is useful to evaluate the health hazards and potential mechanisms of FBs, especially its modified forms in poultry.

3. Discussion

With the development of the broiler industry, the per capita consumption of broilers far exceeds that of pork and beef. However, since the main ingredient of broiler feed is maize, the health of broiler chickens is threatened by mycotoxins, especially fumonisin, which mainly pollutes maize. Broilers fed with a mycotoxin-contaminated feed will not only experience adverse effects on their growth and development, but also cause serious economic losses. At the same time, mycotoxins will accumulate in the edible parts of the broilers and spread to humans through the food chain, posing a threat to human health. Therefore, in this study, the health hazards of FBs and HFBs to broilers were explored, laying a foundation for the establishment of methods to prevent and avoid health hazards in the future.

Many studies have shown that fumonisin could significantly reduce the growth performance of pigs, such as body weight and food intake [

18]. Similarly, the body weight and food intake of broilers were significantly reduced by FBs in our study. The same phenomenon also occurred in the HFBs treatment group. Similar to the results of the previous study, hydrolyzed fumonisin was less toxic than fumonisin, but still had a significant difference compared to the control group [

19]. In addition to reduced growth performance, there were no obvious external clinical symptoms of fumonisin poisoning, such as coughing. Although maize contaminated with mycotoxins may have a reduced oil content, chemical analysis of the diet showed that there was no difference in the main nutritional value between treatments [

20]. Therefore, the decline in growth performance is probably not caused by the difference in nutritional value after mycotoxin contamination, but may be caused by harmful effects after FBs poisoning [

21]. Broiler death occurred in both the control group and the experimental group, and there was no significant difference between the groups, indicating that the death of broilers was not related to fumonisin exposure. This is consistent with the results of previous studies; 20 mg/kg FB1 + FB2 does not cause death in poultry and pigs [

22,

23].

The liver and kidney are the main target organ for fumonisin toxicity. Many studies have shown that fumonisin can induce liver and kidney cell damage in a variety of ways, such as oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy [

24]. Andras found that 10 days after exposure to FB1, the liver showed pathological changes in rats [

25]. Another study also showed that FB1 could significantly affect liver fatty acid metabolism [

26]. We found that both FBs and HFBs could significantly reduce the liver weight and increase the level of ALT in the serum. However, the weight of the kidney and the content of CREA1, UA and BUN in the serum did not change significantly. This phenomenon is consistent with those reported in the literature [

23]. Surprisingly, the weight of the testis was significantly reduced after the emergence of FBs and HFBs, which means that the adverse effects of FBs and HFBs on the male reproductive system are worthy of attention in the future.

The microbiota in animal intestines plays an important role in the health of the host, which is a widely accepted fact [

18,

27]. Many immune and metabolic diseases, such as chronic inflammation, obesity, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease and atherosclerosis, are likely to be related to the imbalance of intestinal microbiota [

28,

29,

30]. Increasing attention has been given to the balance of intestinal microbiota [

31,

32]. Researchers found that fumonisin could alter the intestinal barrier in broilers [

33]. Additionally, Zhang and co-researchers reported the response of the fecal bacterial microbiota to FB1 exposure in BALB/c mice [

34]. However, there are few studies on the effect of fumonisin on the intestinal microbiota of animals, such as weaned pigs and broilers. In this study, FBs and HFBs affected the intestinal microbiota of broilers, particularly the H-FBs.

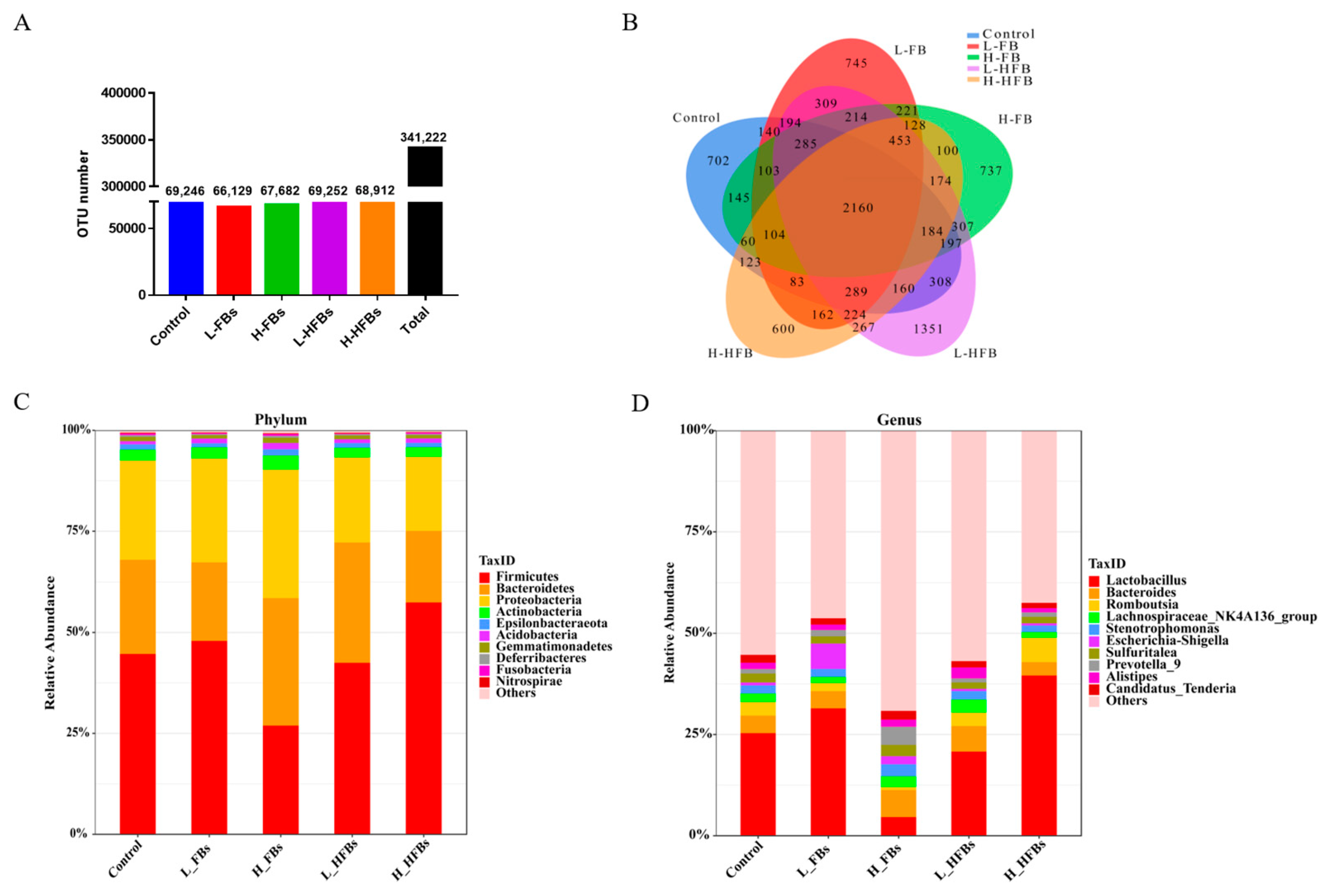

The three predominant bacterial phyla in this study were

Firmicutes,

Bacteroidetes and

Proteobacteria. is the predominant Gram-negative bacterial phylum in the gastrointestinal tract, and is a major participant in the healthy state and complex homeostasis protected by the gut microbiota. An abnormal distribution of

Bacteroides could cause growth retardation, immune disorders and metabolic disorders [

35,

36].

Bacteroides and

Firmicutes are also related to obesity. A higher quantity of

Firmicutes in the intestine leads to a more effective absorption of calories from food, possibly causing obesity. Studies have shown that the number of

Firmicutes in the intestine of obese mice is higher than that of

Bacteroides.

Bacteroides have beneficial effects on body weight gain and insulin sensitivity in high-fat diet-induced obese mice [

37,

38,

39]. When pigs were fed wheat contaminated with deoxynivalenol (DON), the abundance levels of

Firmicutes and

Bacteroides in the cecum, colon and ileum changed [

40]. In our results, there was no difference in

Bacteroidetes,

Proteobacteria or

Firmicutes among the different groups due to individual differences, but the ratio of

Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes was lower in the H-FBs group (the

p-value between L-FBs and H-FBs was 0.0896), which may explain the weight loss of the broilers. These results confirm the results obtained in previous studies.

Proteobacteria are spoilage bacteria and often appear in the intestines of humans and animals. When the intestines are exposed to contaminants,

Proteobacteria increase significantly [

41].

Proteobacteria can affect the function of the gastrointestinal tract and cause many diseases [

42]. After fumonisin exposure,

fusobacteria also appeared on the list of dominant strains, which can cause mucosal infections and enteritis [

43]. These gut-damaging factors can affect the absorption of nutrients, leading to poor broiler growth.

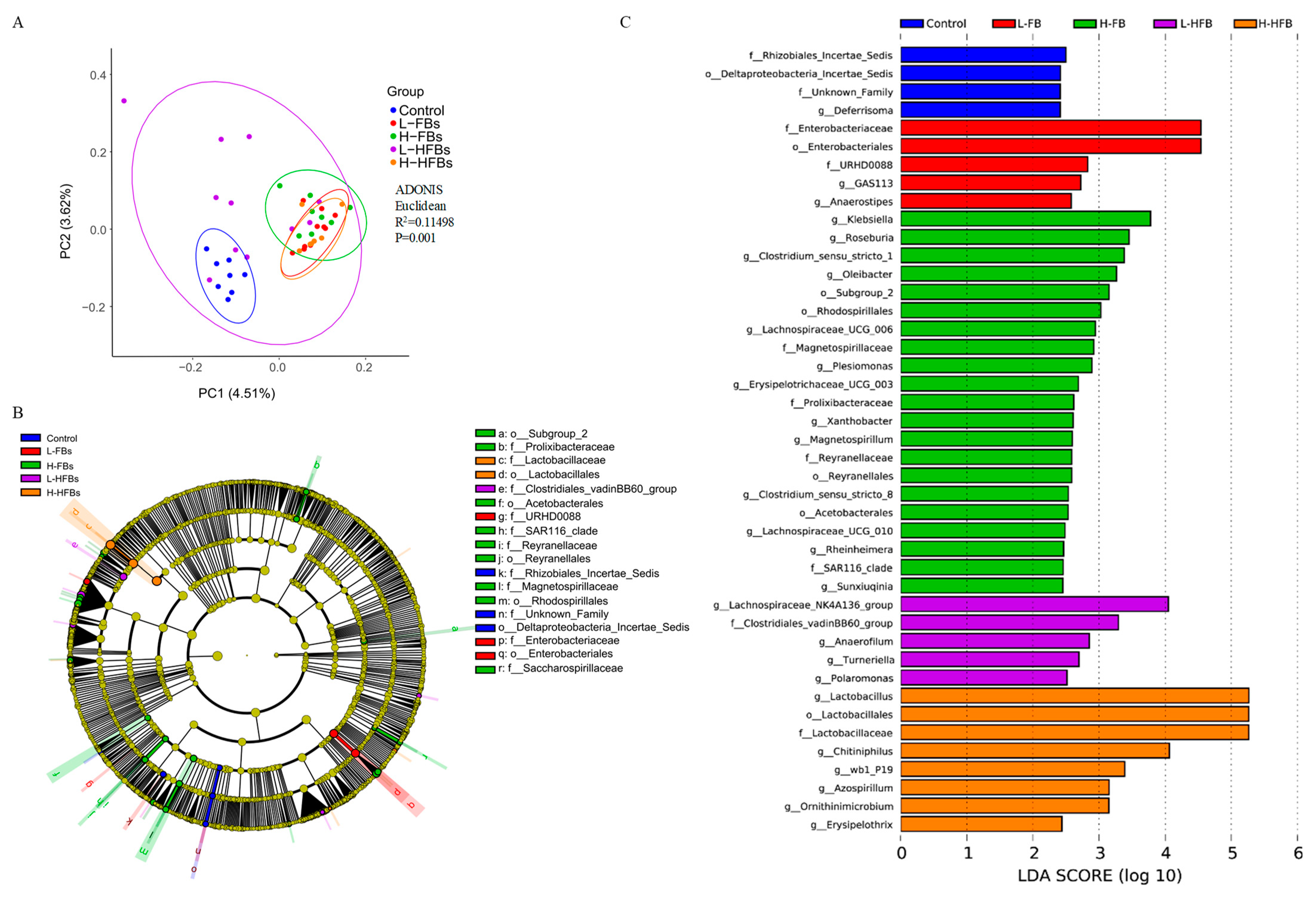

LEfSe analysis indicated that most of the differential species belonged to

Proteobacteria and

Firmicutes. However, each treatment group mainly affected different microorganisms. The FBs group mainly affected

Klebsiella and

Anaerostipes. As pathogenic microorganisms, they could infect many organs and cause functional damage, including to the intestinal tract [

44,

45]. The HFBs group mainly affected

Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group and

Chitiniphilus. Interestingly, a kind of beneficial bacteria,

Lactobacillus, was lower in the H-FBs group, while it was in relatively high abundance in the H-HFBs group, indicating a difference between H-FBs and H-HFBs.

Mycotoxin was mainly excreted through the intestine to the feces [

46]. The excessive accumulation of mycotoxin may lead to the destruction of the intestinal microbial balance. Chang and co-workers reported that when aflatoxin and zearalenone were degraded by microorganisms (

Bacillus subtilis,

Lactobacillus casei and

Candida utilis), the abnormal intestinal microbes caused by aflatoxin and zearalenone in broilers were significantly alleviated [

47]. Li and co-workers also found that the application of

Clostridium sp.

WJ06 can reduce the toxic effects of DON and recover the intestinal microecosystem of growing pigs [

40]. Our results show that as the treatment time increases, the fumonisin level in the feces shows an increasing trend. The imbalance of intestinal microbials may be caused by excessive fumonisin accumulated in the intestine. Furthermore, the bioavailability of HFB1 in rats is greater than that of FB1 [

15]. Our results also reveal that even if the exposure dose of fumonisin and the modified form are the same, the level of toxins in the feces of the HFBs group is much lower than that in the FBs group, which means that the modified fumonisin may have higher bioavailability or be easily transformed, making itself difficult to be detected by current approaches.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Chemicals and Materials

FB1, B2 and B3 were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). HFB1 was obtained from Romer. Ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ·cm) was supplied by Millipore (Bedford, MA, USA). Acetonitrile and methanol (HPLC grade) were purchased from Honeywell (Morristown, NJ, USA). Formic acid (HPLC grade) was obtained from Anpel (Shanghai, China). Cleanert MC clean-up columns were obtained from Bonna-Agela Technologies (Tianjin, China). Maize grains were purchased from a local market in Shanghai, China. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits were purchased from Wako (Kanto, Japan). Potato dextrose agar medium (PDA) and blood collection tubes were purchased from BD Difco (San Diego, CA, USA).

5.2. Experimental Animals and Feeding

Sixty male one-day-old Pudong Sanhuang broiler chickens were obtained from Shanghai Veterinary Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Shanghai, China). The experiment was approved by the Welfare and Ethics Committee of Experimental Animals in Shanghai Veterinary Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Shanghai, China). The Ethical approval code was SV-20200906-Y06. Additionally, the Ethical approval date was 6 September 2020. Animal experiments followed the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

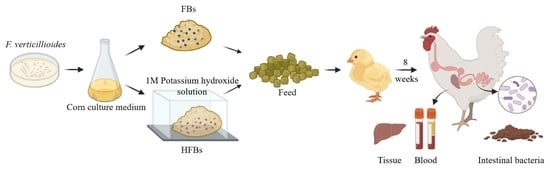

The broilers were randomly divided into five groups: control group, L-FBs group (low-level fumonisin Bs), H-FBs (high-level fumonisin Bs), L-HFBs (low-level hydrolyzed fumonisin Bs) and H-HFBs (high-level hydrolyzed fumonisin Bs) groups, with 12 replicates per group. After a 1-week observation period, the experiment was conducted for 8 weeks after changing to the mycotoxin-containing feed. Animals were housed in stainless steel cages with free access to water and food. Animal body weight and feed consumption were recorded during the experiment.

5.3. Preparation of the Experimental Feed

F. verticillioides BJ6 was isolated by our laboratory. Additionally, the strain was maintained as spore suspensions in 20% glycerol at −80 °C. F. verticillioides BJ6 was inoculated into PDA medium and cultured at 25 °C for 7 days. Maize grains were irradiated with a cobalt radiation source (8–10 kGy) for sterilization and then put into conical flask and rehydrated to water activity (aw) 0.99 by the addition of sterile distilled water as a maize culture medium. Due to a lack of relevant standards, FB1, FB2, FB3 and HFB1 were detected, and the different groups were:

Control group: maize culture medium was inoculated with blank PDA medium, cultured at 25 °C for 10 days, crushed and mixed evenly with ordinary broiler feed. The diet composition in the ordinary broiler feed is shown in

Table 6. The concentration of FB1, FB2, FB3 and HFB1 was 74.10 μg/kg, 15.93 μg/kg, 12.16 μg/kg and 7.75 μg/kg in the ordinary broiler feed, respectively.

FBs group: maize culture medium was inoculated with F. verticillioides BJ6 colonies taken from the edges of old colony-edge bacteria, cultured at 25 °C for 10 days, crushed and mixed evenly with ordinary broiler feed. The concentration of FBs was 10 mg/kg (FB1 + FB2 + FB3) in the L-FBs group and 20 mg/kg (FB1 + FB2 + FB3) in the H-FBs group.

HFBs group: maize meal containing FBs was converted into HFBs through alkaline hydrolysis (all FBs disappeared) and mixed evenly with ordinary broiler feed. The doses were the same as the FBs group.

5.4. Mycotoxins Extraction

Samples were dried at 65 °C and milled into 0.45 mm flour. Briefly, 1 ± 0.05 g samples were extracted by 10 mL extracting solution (acetonitrile:water:formic acid = 840:159:1,

v/v). Samples were shaken at 2500 rpm/min in an orbital shaker for 20 min and then ultrasonicated for 30 min. Then, they were centrifuged at 4000 rpm/min for 10 min. Cleanert MC columns were used to purify the supernatant. One milliliter of purified supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm nylon filter and stored in sampler vials at −20 °C until high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis, and the analysis method was the same as that described in a previous article [

3].

5.5. Collection and Analysis of Blood and Tissue Samples

After 8 weeks of feeding, the broilers were sacrificed by exsanguination from the jugular vein after taking a blood sample from the wing vein. Blood was stored in procoagulant tubes and anticoagulant tubes. Serum samples were separated by centrifugation (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA) of the blood at 1200× g for 10 min at 4 °C. All of the samples were temporarily stored at 4 °C and tested within a day. The serum samples were analyzed using ELISA kits (Wako, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and detected in an automatic biochemical analyzer (HITACHI, Tokyo, Japan). Hemograms were generated using a BC-3800 Automated Hematology Analyzer (Shenzhen, China). For conventional analysis, the liver, kidney, and testicles were collected and weighed.

5.6. Sequencing, Data Processing and Analysis of 16S rRNA Amplicons of Intestinal Bacteria

Sequencing and preliminary data processing were conducted by OE Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Total genomic DNA was extracted from the jejunum contents using a DNA Extraction Kit (Magen, Guangzhou, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of DNA was verified with a NanoDrop2100 (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA) and agarose gel electrophoresis. The genomic DNA was used as a template for PCR (V3–V4 variable regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA genes) amplification with the primers 343F (5′-TAC GGR AGG CAG CAG-3′) and 798R (5′-AGG GTA TCT AAT CCT-3′) and Tks Gflex DNA Polymerase (Takara, Tokyo, Japan)). The first PCR reactions were conducted using the following program: 5 min of pre-degeneration at 94 °C, 26 cycles of 30 s for degeneration at 94 °C, 30 s for annealing at 56 °C, 20 s for elongation at 72 °C, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The samples were stored at 4 °C after the reaction. The amplicon quality was visualized using gel electrophoresis, purified with AMPure XP beads according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Agencourt, San Diego, CA, USA), and amplified for another round of PCR. The second PCR reactions were conducted using the following program: 5 min of pre-degeneration at 94 °C, 7 cycles of 30 s for degeneration at 94 °C, 30 s for annealing at 56 °C, 20 s for elongation at 72 °C, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The samples were stored at 4 °C after the reaction. After purification with AMPure XP beads, the final amplicon was quantified using a Qubit dsDNA assay kit (Life Technologies, Waltham, MA, USA). Equal amounts of purified amplicons were pooled for subsequent sequencing.

Paired-end reads of raw fastq files were preprocessed using Trimmomatic software [

48] with the following parameters: (1) ambiguous bases (N) were cut off, and (2) low-quality sequences with an average quality score below 20 were cut off using a sliding window trimming approach. After trimming, paired-end reads were assembled using FLASH software [

49] with the following parameters: (1) minimal overlapping was 10 bp; (2) maximum overlapping was 200 bp; and (3) the maximum mismatch rate% was 20%. The sequences were further denoised and the reads were removed with chimeras using QIIME software (version 1.8.0) [

50] to produce clean reads. Then, the clean reads were subjected to primer sequence removal and clustering to generate operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using Vsearch software (Rognes et al., 2016) with a 97% similarity cut-off. The representative read of each OTU was selected using the QIIME package and annotated and blasted against the Silva database (Version 138) using the RDP classifier [

51] (the confidence threshold was 70%).

Data was uploaded to National Center for Biotechnology Information which can be downloaded by using BioProject ID: PRJNA784726.

5.7. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with the Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (parametric test) or Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (non-parametric test) to assess the differences between the groups using the GraphPad Prism 7.00, and the values are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and the level of significance in this manuscript was set at *, p < 0.0332; **, p < 0.0021; ***, p < 0.0002; ****, p < 0.0001.