Green Pit Viper Envenomations in Bangkok: A Comparison of Follow-Up Compliance and Clinical Outcomes in Older and Younger Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

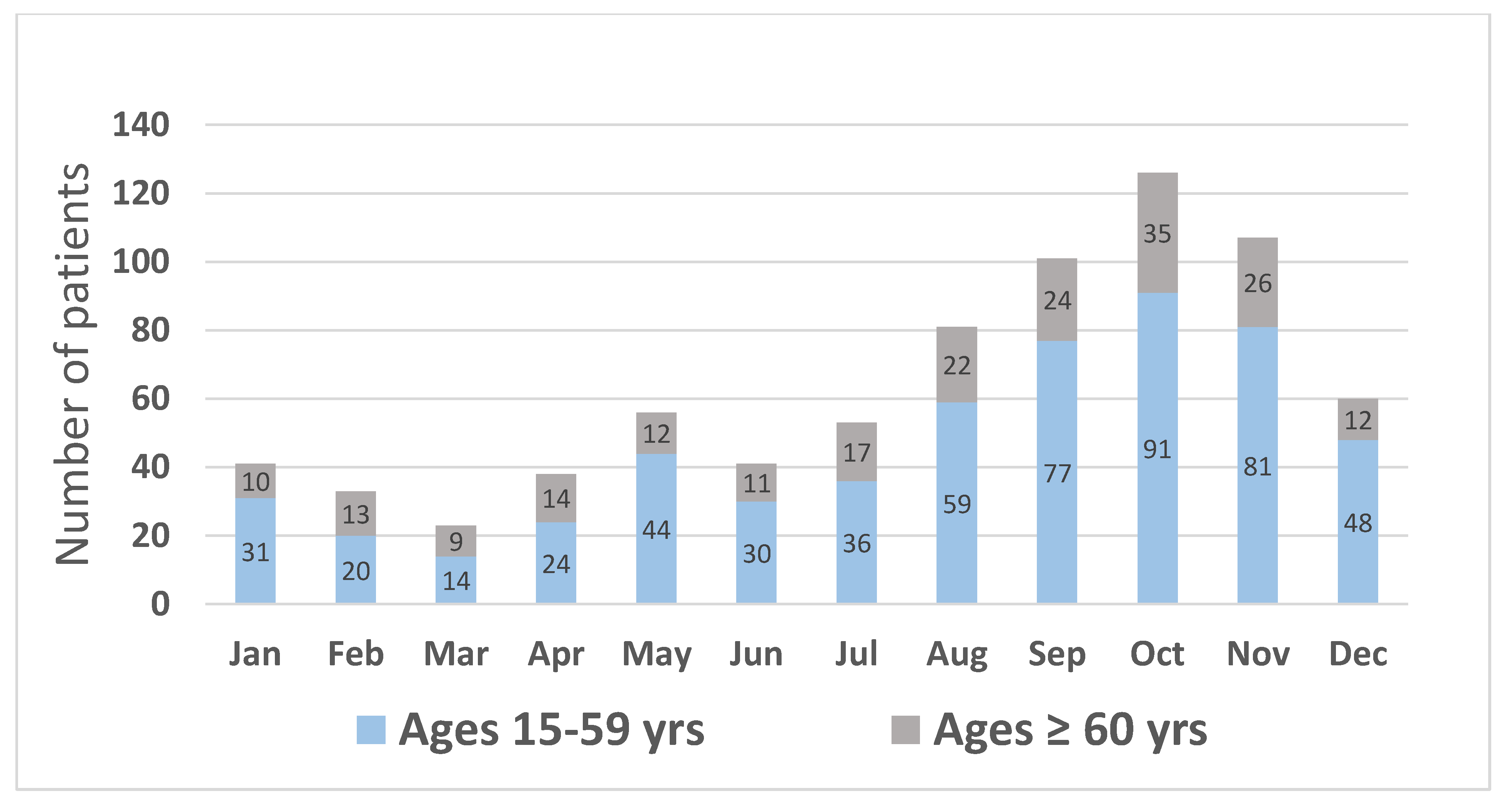

2.1. Patient Characteristics

2.2. Bite Information (Table 1)

2.3. Clinical Features (Table 1)

2.4. Laboratory Results (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S1)

| Total (n= 760) | Ages < 60 Years (n = 555) | Ages ≥ 60 Years (n = 205) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Outcome | ||||

| 83/760 (10.9) | 56/555 (10.1) | 27/205 (13.2) | 0.23 |

| 54/760 (7.1) | 37/555 (6.7) | 17/205 (8.3) | 0.44 |

| 16/707 (3.3) | 10/514 (2.0) | 6/193 (3.1) | 0.35 |

| 5/78 (6.4) | 4/51 (7.8) | 1/27 (4.7) | 0.48 |

| 19/502 (3.8) | 11/349 (3.2) | 8/153 (5.2) | 0.26 |

| 39 (5.1) | 28 (5.1) | 11 (5.4) | 0.86 |

| Treatment outcome | ||||

| Disposition after initial ED management | ||||

| 738 (97.1) | 535 (96.4) | 203 (99.0) | 0.41 |

| 6 (0.8) | 5 (0.9) | 1 (0.5) | |

| 13 (1.7) | 12 (2.1) | 1 (0.5) | |

| 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Disposition after ED observation | 738 (97.1) | 535 (96.4) | 203 (99.0) | |

| 668 (90.5) | 486 (90.8) | 182 (89.7) | 0.77 |

| 30 (4.1) | 20 (3.7) | 10 (4.9) | |

| 40 (5.4) | 29 (5.4) | 11 (5.4) | |

| Hospital admission (at any point) | 67 (8.8) | 50 (9.0) | 17 (8.3) | 0.76 |

| In-hospital discharge status | ||||

| 67 (8.8) | 50 (9.0) | 17 (8.3) | 0.76 |

2.5. Treatment

2.6. Follow-Ups

3. Discussion

4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

6. Materials and Methods

6.1. Definitions

- -

- Abnormal blood test for coagulation: (coagulopathy): VCT > 20 min, or abnormal 20WBCT (unclotted blood at 20 min), platelet count less than 100,000 cells/mm3, fibrinogen < 100 mg/dL, or INR >1.2;

- -

- Administration of antivenom: patient received GPV antivenom (F(ab’)2) produced by the Queen Saovabha Memorial Institute (QSMI) if he/she had coagulopathy or abnormal bleeding or signs of impending compartment syndrome/compartment syndrome [25]. The dose was 3–5 vials. The antivenom is a dry powder and needs reconstituting by adding 10 mL of sterile water per vial;

- -

- Administration of blood components: patient received blood components due to abnormal bleeding from the GPV bite;

- -

- If patient had surgical intervention: patient underwent any of the following: incision and drainage, wound debridement, fasciotomy, or limb amputation;

- -

- If patient had an invasive procedure: patient underwent or received any of the following: intubation, central vein catheterization, or hemodialysis;

- -

- If vasopressors were administered: patient received an intravenous infusion of any vasopressor drugs (adrenaline, noradrenaline, dopamine) to improve hemodynamics.

- -

- ED revisit: In case of out-patient follow-up, the patient had an ED revisit when he/she returned to the ED without an appointment within 72 ± 12 h;

- -

- Discharge status: In case the patient was admitted to the hospital as an inpatient. The patient’s final status after being treated in the hospital was described as: (1) alive with complete recovery; (2) alive with disability (such as limb loss); (3) alive with permanent neurological deficits, such as muscle weakness (in case of intracranial bleeding); (4) dead (hospital death); or (5) against medical advice.

6.2. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eakumpan, S. Snake bite envenoming. In Annual Epidemiological Surveillance Report 2018; Chaifoo, W., Artkian, W., Choomkasian, P., Eds.; Canna Graphic Limited Partnership: Bangkok, Thailand, 2018; pp. 214–216. ISBN 978-616-11-4161-5. Available online: https://apps-doe.moph.go.th/boeeng/download/AW_Annual_Mix6212_14_r1.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Mahasandana, S.; Jintakune, P. The species of green pit viper in Bangkok. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 1990, 21, 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Othong, R.; Keeratipornruedee, P. A study regarding follow-ups after green pit viper bites treated according to the practice guideline by the Ministry of Public Health of Thailand. Clin. Toxicol. 2020, 58, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutton, R.A.; Looareesuwan, S.; Ho, M.; Silamut, K.; Chanthavanich, P.; Karbwang, J.; Supanaranond, W.; Vejcho, V.; Viravan, C.; Phillips, R.E.; et al. Arboreal green pit vipers (genus Trimeresurus) of South-East Asia: Bites by T. albolabris and T. macrops in Thailand and a review of the literature. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1990, 84, 866–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradniwat, P.; Rojnuckarin, P. Snake venom thrombin-like enzymes. Toxin Rev. 2014, 33, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradniwat, P.; Rojnuckarin, P. The GPV-TL1, a snake venom thrombin-like enzyme (TLE) from a green pit viper (Trimeresurus albolabris), shows a strong fibrinogenolytic activity. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2014, 6, 275–283. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, N.H.; Fung, S.Y.; Yap, Y.H.Y. Isolation and characterization of the thrombin-like enzyme from Cryptelytrops albolabris (white-lipped tree viper) venom. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2012, 161, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojnuckarin, P.; Intragumtornchai, T.; Sattapiboon, R.; Muanpasitporn, C.; Pakmanee, N.; Khow, O.; Swasdikul, D. The effects of green pit viper (Trimeresurus albolabris and Trimeresurus macrops) venom on the fibrinolytic system in human. Toxicon 1999, 37, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojnuckarin, P.; Mahasandana, S.; Intragumtornchai, T.; Swasdikul, D.; Sutcharitchan, P. Moderate to severe cases of green pit viper bites in Chulalongkorn hospital. Thai. J. Hematol. Trans. Med. 1996, 6, 199–205. [Google Scholar]

- Blessmann, J.; Nguyen, T.P.N.; Bui, T.P.A.; Krumkamp, R.; Vo, V.T.; Nguyen, H.L. Incidence of snakebites in 3 different geographic regions in Thua Thien Hue province, central Vietnam: Green pit vipers and cobras cause the majority of bites. Toxicon 2018, 156, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, J.L.; Tan, N.H.; Tan, C.H. Proteomics and preclinical antivenom neutralization of the mangrove pit viper (Trimeresurus purpureomaculatus, Malaysia) and white-lipped pit viper (Trimeresurus albolabris, Thailand) venoms. Acta Trop. 2020, 209, 105528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Management of Snakebites, 2nd ed.; Publishing and Sales, World Health Organization: New Delhi, India, 2016; ISBN 978-92-9022-530-0. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health. Practice Guideline for Management of Patients with Snake Bite; Department of Medical Services; Ministry of Public Health: Bangkok, Thailand, 2004; ISBN 974-465-537-2. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/382171851/snake-pdf (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Rojnuckarin, P.; Suteparak, S.; Sibunruang, S. Diagnosis and management of venomous snakebites in Southeast Asia. Asian Biomed. 2012, 6, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prachuabmoh, V. Aging in Thailand. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/unpd_egm_201902_s3_vipanprachuabmoh.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Budnitz, D.S.; Lovegrove, M.C.; Shehab, N.; Richards, C.L. Emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older Americans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 2002–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debray, M.; Pautas, E.; Couturier, P.; Franco, A.; Siguret, V. Oral anticoagulants in the elderly. Rev. Med. Interne 2003, 24, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teerawichitchainan, B.; Knodel, J.; Pothisiri, W. What does living alone really mean for older persons? A comparative study of Myanmar, Vietnam, and Thailand. Demogr. Res. 2015, 32, 1329–1360. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/26350154 (accessed on 28 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Chantakeeree, C.; Sormunen, M.; Estola, M.; Jullamate, P.; Turunen, H. Factors affecting quality of life among older adults with hypertension in urban and rural areas in thailand: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2021, 95, 222–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.; Offerman, S.; Vohra, R.; Wolk, B.; LaPoint, J.; Quan, D.; Spyres, M.; LoVecchio, F.; Thomas, S.H. Assessing the effect of a medical toxicologist in the care of rattlesnake-envenomated patients. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2018, 25, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyres, M.B.; Ruha, A.M.; Kleinschmidt, K.; Vohra, R.; Smith, E.; Padilla-Jones, A. Epidemiology and clinical outcomes of snakebite in the elderly: A ToxIC database study. Clin. Toxicol. 2018, 56, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, I.; Van Sluijs, E.M.F.; Ogilvie, D. Physical activity and transitioning to retirement: A systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 43, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanhome, L.; Cox, M.J.; Vasaruchapong, T.; Chaiyabutr, N.; Sitprija, V. Characterization of venomous snakes of Thailand. Asian Biomed. 2011, 5, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojnuckarin, P.; Mahasandana, S.; Intragumthornchai, T.; Sutcharitchan, P.; Swasdikul, D. Prognostic factors of green pit viper bites. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1998, 58, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotenimitkhun, R.; Rojnuckarin, P. Systemic antivenom and skin necrosis after green pit viper bites. Clin. Toxicol. (Phila). 2008, 46, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pongpit, J.; Limpawittayakul, P.; Juntiang, J.; Akkawat, B.; Rojnuckarin, P. The role of prothrombin time (PT) in evaluating green pit viper (Cryptelytrops sp.) bitten patients. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012, 106, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thumtecho, S.; Tangtrongchitr, T.; Srisuma, S.; Kaewrueang, T.; Rittilert, P.; Pradoo, A.; Tongpoo, A.; Wananukul, W. Hematotoxic manifestations and management of green pit viper bites in Thailand. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2020, 16, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriengkrairut, S.; Othong, R. Bacterial infection secondary to Trimeresurus species bites: A retrospective cohort study in a university hospital in Bangkok. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2021, 33, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (n= 760) | Ages < 60 (n = 555) | Ages ≥ 60 (n = 205) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year), median (IQR) | 48 (30–61) | 40 (26–51) | 68 (64–75) | <0.001 * |

| Male, n (%) | 423 (55.7) | 322 (58) | 101 (49.3) | 0.03 * |

| Underlying, n (%) | 218 (28.7) | 104 (18.7) | 114 (55.6) | <0.001 * |

| 198 (26.1) | 92 (16.6) | 106 (51.7) | <0.001 * |

| 94 (12.4) | 29 (5.2) | 65 (31.7) | <0.001 * |

| 41 (5.4) | 11 (2) | 30 (14.6) | <0.001 * |

| 22 (2.9) | 10 (1.8) | 12 (5.9) | 0.003 * |

| 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0.29 |

| Type of GVP bite, n (%) | 0.01 * | |||

| 721 (94.9) | 524 (94.4) | 197 (96.0) | |

| 326 (43.0) | 223 (40.2) | 103 (50.2) | |

| 172 (22.6) | 140 (25.2) | 32 (15.6) | |

| 223 (29.3) | 161 (29.0) | 62 (30.2) | |

| 39 (5.1) | 31 (5.6) | 8 (4.0) | |

| Current medication, n (%)(only antiplatelets, anticoagulants, or both) | 19 (2.5) | 5 (0.9) | 14 (6.8) | <0.001 * |

| Bite scene, n (%) | 0.33 | |||

| 132 (17.4) | 97 (17.5) | 35 (17.1) | |

| 166 (21.8) | 112 (20.2) | 54 (26.3) | |

| 143 (18.8) | 107 (19.3) | 36 (17.6) | |

| 319 (42.0) | 239 (43.0) | 80 (39.0) | |

| Elapsed time (min), median (IQR) | 55 (30–120) | 47 (30–118) | 69 (35–150) | 0.001 * |

| Elapsed time, n (%) | 0.002 * | |||

| 152 (20.0) | 122 (22.0) | 30 (14.6) | |

| 238 (31.3) | 186 (33.5) | 52 (25.4) | |

| 187 (24.6) | 122 (22.0) | 65 (31.7) | |

| 183 (24.1) | 125 (22.5) | 58 (28.3) | |

| Tetanus vaccination, n (%) | 0.56 | |||

| 379 (49.9) | 285 (51.3) | 94 (45.9) | |

| 36 (4.7) | 26 (4.7) | 10 (4.9) | |

| 40 (5.3) | 26 (4.7) | 14 (6.8) | |

| 111 (14.6) | 77 (13.9) | 34 (16.5) | |

| 194 (25.5) | 141 (25.4) | 53 (25.9) | |

| Vital signs at first ED visit | ||||

| 140 (126–159) | 137 (123–152) | 154 (135–170) | <0.001 * |

| 84 (75–94) | 84 (74–94) | 84 (75–93) | 0.84 |

| 85 (76–96) | 86 (76–97) | 80 (74–94) | 0.03 * |

| 19 (5) | 19 (5) | 19 (1) | 0.92 |

| Bite site, n (%) | <0.001* | |||

| 465 (61.2) | 373 (67.2) | 92 (44.9) | |

| 225 (29.6) | 131 (23.6) | 94 (45.9) | |

| 70 (9.2) | 51 (9.2) | 19 (9.2) | |

| Severity of local reactions, n (%) | 0.49 | |||

| 4 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (1.0) | |

| 31 (4.1) | 24 (4.3) | 7 (3.4) | |

| 168 (22.1) | 118 (21.3) | 50 (24.4) | |

| 535 (70.4) | 397 (71.5) | 138 (67.3) | |

| 22 (2.9) | 14 (2.5) | 8 (3.9) | |

| Hemorrhagic bleb | 20 (2.7) | 16 (3.0) | 4 (2.0) | 0.48 |

| Wound necrosis | 6 (0.8) | 5 (0.9) | 1 (0.5) | 0.57 |

| Other systemic symptoms from envenomation (before receipt of treatment) | ||||

| 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.54 |

| 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.5) | 0.46 |

| 5 (0.7) | 5 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.33 |

| 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.5) | 0.46 |

| Follow-Up Compliance | Total † n= 674 | Ages < 60 n = 491 | Ages ≥ 60 n=183 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 238 (35.3) | 159 (32.4) | 79 (43.2) | 0.01 * |

| 436 (64.7) | 332 (67.6) | 104 (56.8) |

| Details of Incomplete Follow-Up | Total † (n = 436) | Ages < 60 (n = 332) | Ages ≥ 60 (n = 104) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 116 (26.6) | 94 (28.3) | 22 (21.2) | 0.04 * |

| 190 (43.6) | 149 (44.9) | 41 (39.4) | |

| 130 (29.8) | 89 (26.8) | 41 (39.4) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Othong, R.; Eurcherdkul, T.; Chantawatsharakorn, P. Green Pit Viper Envenomations in Bangkok: A Comparison of Follow-Up Compliance and Clinical Outcomes in Older and Younger Adults. Toxins 2022, 14, 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins14120869

Othong R, Eurcherdkul T, Chantawatsharakorn P. Green Pit Viper Envenomations in Bangkok: A Comparison of Follow-Up Compliance and Clinical Outcomes in Older and Younger Adults. Toxins. 2022; 14(12):869. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins14120869

Chicago/Turabian StyleOthong, Rittirak, Thanaphat Eurcherdkul, and Prasit Chantawatsharakorn. 2022. "Green Pit Viper Envenomations in Bangkok: A Comparison of Follow-Up Compliance and Clinical Outcomes in Older and Younger Adults" Toxins 14, no. 12: 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins14120869

APA StyleOthong, R., Eurcherdkul, T., & Chantawatsharakorn, P. (2022). Green Pit Viper Envenomations in Bangkok: A Comparison of Follow-Up Compliance and Clinical Outcomes in Older and Younger Adults. Toxins, 14(12), 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins14120869