Lycopene Supplement and Blood Pressure: An Updated Meta-Analysis of Intervention Trials

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction of Studies

2.4. Quality Assessment of Studies

2.5. Statistical Methods

3. Results

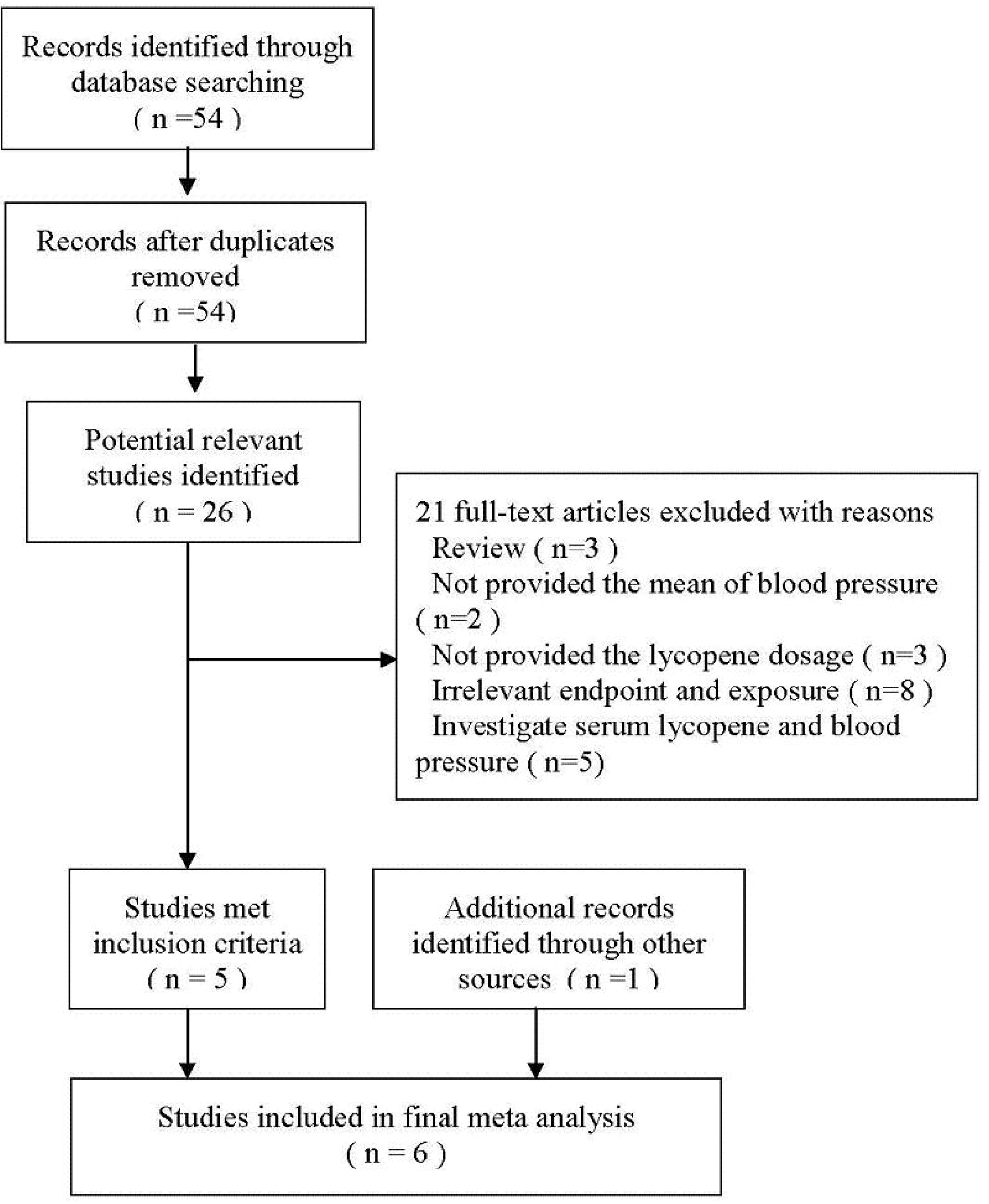

3.1. Literature Selection

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.3. Quality Assessment of Selected Studies

3.4. Meta-Analyses Results

3.4.1. Effect of Lycopene Supplement on Blood Pressure

| Study, year (reference), region | Study design | Source of lycopene/control | Dosage (mg)/day | Duration | Change of BP treatment vs. control | Participants, m/f, age | Sample size | Other source of lycopene | Assessment of dietary intake |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thie, 2012 [26], Aberdeen, Scotland | single-blind, RCT | L1: tomato extract capsule (purchased from Holland and Barret) L2: tomato-based foods C: placebo capsule | L1: 10 L2: 10 C: 0 | 16 weeks | SBP: −3.2 vs. −0.3 DBP: −1 vs. −0.7 | men and women; aged 51 years | L: 68 T: 81 C: 76 | no other dietary supplements were allowed | by using seven-day food diaries before and during the run-in period as well as during the intervention |

| Kim, 2011 [14], Yonsei, Asia | double-blind, RCT | L: tomato extract capsule (Lyc-O-Mato) C: placebo capsule | L1: 6 L2: 15 C: 0 | 8 weeks | SBP: −3.2 vs. −0.6 | healthy male, smoker or alcohol-drinker, low intake of fruits and vegetables; male, 33.5–34.8 years | L1:41 L2: 37 C: 38 | negligible | by 24-h recall method and semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire |

| Ried, 2009 [15], Australia, Oceania | double-blind, RCT, three-group parallel trial | L: tomato extract capsule (Lyc-O-Mato) C: Placebo capsule | L: 15 C: 0 | 8 weeks | SBP: −2.5 vs. −4.9 DBP: −1.6 vs. −0.5 | prehypertensive adults, with no antihypertensive drugs; 12 m/13 f, 52 ± 12 years | L: 15 C: 10 | negligible | by questionnaires and participants’ daily diary entries |

| Paran, 2009 [16], Israel, Asia | double-blind, placebo controlled, two-group crossover trial | L: tomato extract capsule (Lyc-O-Mato) C: placebo capsule | L: 15 C: 0 | 6 weeks | SBP: −13.6 vs. −2.1 DBP: −4.2 vs. −2.1 | mild hypertensives, with one or two antihypertensive drugs; 26 m/24 f, 56 ± 10 years | L: 50 C: 50 | no other dietary supplements were allowed | by dietary query |

| Engelhard, 2006 [13], Israel, Asia | single-blind, placebo controlled trial | L: tomato extract capsule (Lyc-O-Mato) C: placebo capsule | L: 15 C: 0 | 8 weeks | SBP: −9.98 vs. −1.05 DBP: −4.06 vs. −1.46 | mild hypertensives, non-smokers with no antihypertensive drugs, 18 m/13 f, 52 ± 21 years | L: 31 C: 31 | no other dietary supplements were allowed | by dietary questionnaire |

| Paterson, 2006, [20], U.K, Europe | single-blind, RCT | L: carotenoid-rich canned soups C: carotenoid-poor canned soups | L: 4.5 C: 0 | 4 weeks | SBP: 1 vs. 2 DBP: 1 vs. 2 | healthy adult, 12 m/24 f, 43.5 ± 23.5 years | L: 36 C: 36 | included | by a three-day estimated diet diary |

| Study ID | Randomization | Allocation concealment | Blinding | Loss to follow-up | Dietary advice | Compliance | Funding source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thie, 2012, Scotland [26] | randomized | single-blind | 22/247 | control group was restricted | assessed by measuring serum lycopene concentrations and by analyzing a weekly checklist of tomato-based foods consumed. | funding from the Scottish Government (RESAS). | |

| Kim, 2011, Yonsei [14] | randomized | double-blind | 10/126 | maintain their usual lifestyle and dietary habits | assessed using pill counting, food records, and measurement of plasma lycopene levels | National Research Foundation, Korea Health 21 R & D Projects | |

| Ried, 2009 Australia [15] | permuted block randomization using the SAS 9.1 software package | sequentially numbered containers | double-blind | 3/39 | maintain their usual diet and physical activity | assessed using participants daily diary entries | RACGP 2006 Pfizer Cardiovascular Research Grant, Australian Government Primary Health Care Research Evaluation Development (PHCRED) Program |

| Paran, 2009, Israel [16] | non-randomized | ? | double-blind | 0/50 | no other dietary supplements were allowed and to keep their usual dietary and exercise habits | verified by counting the remaining capsules and by reinforcement at each visit | No funding source provided |

| Engelhard, 2006, Israel [13] | non-randomized | ? | single-blind | 3/34 | no other dietary supplements were allowed and to keep their usual dietary habits | by counting the remaining capsules and by reinforcement at each visit | no funding source provided |

| Paterson, 2006, UK [20] | block-randomization stratified by age, gender, BMI | ? | single-blind | 0/36 | comprehensive food diaries | assessed by the return of unused products at the end of each intervention period | Unilever Best foods and the University of Reading Research Endowment Trust Fund |

3.4.2. Results of Subgroup Analyses

| Group | Total data included | WMD (95% CI) | p | p for heterogeneity | I2, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 6 | −4.953 (−8.820, −1.086) | 0.012 | 0.034 | 58.5 |

| Baseline of SBP | |||||

| <120 mmHg | 3 | −1.441 (−5.320, 2.439) | 0.467 | 0.731 | 0.0 |

| >120 mmHg | 3 | −8.034 (−12.411, −3.656) | 0.000 | 0.139 | 49.4 |

| Dosage of lycopene | |||||

| <12 mg/day | 2 | −1.953 (−6.473, 2.568) | 0.397 | 0.680 | 0.0 |

| >12 mg/day | 4 | −6.350 (−11.342, −1.358) | 0.013 | 0.042 | 63.4 |

| Duration of intervention | |||||

| >8 weeks | 4 | −4.324 (−8.753, 0.105) | 0.056 | 0.100 | 52.1 |

| <8 weeks | 2 | −6.320 (−16.609, 3.969) | 0.229 | 0.018 | 82.0 |

| Location | |||||

| Asia | 3 | −7.661 (−12.480, −2.842) | 0.002 | 0.069 | 62.7 |

| Other regions | 3 | −1.368 (−5.573, 2.838) | 0.524 | 0.723 | 0.0 |

| Funding | |||||

| Support by funding | 4 | −4.481 (−9.821, 0.859) | 0.100 | 0.061 | 59.3 |

| No-support by funding | 2 | −5.363 (−13.095, 2.369) | 0.174 | 0.041 | 76.1 |

| Group | Total data included | WMD (95% CI) | p | p for heterogeneity | I2, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 5 | −0.315 (−0.687, 0.057) | 0.097 | 0.555 | 0 |

| Baseline of DBP | |||||

| <80 mmHg | 3 | −0.308 (−0.683, 0.068) | 0.108 | 0.927 | 0.0 |

| >80 mmHg | 2 | −0.408 (−5.003, 4.188) | 0.862 | 0.095 | 64.1 |

| Dosage of lycopene | |||||

| <12 mg/day | 2 | −0.305 (−0.681, 0.071) | 0.111 | 0.750 | 0.0 |

| >12 mg/day | 3 | −0.629 (−3.746, 2.489) | 0.693 | 0.247 | 28.6 |

| Duration of intervention | |||||

| >8 weeks | 3 | −0.328 (−0.703, 0.046) | 0.086 | 0.434 | 0.0 |

| <8 weeks | 2 | 0.562 (−2.476, 3.600) | 0.717 | 0.314 | 1.4 |

| Location | |||||

| Asia | 2 | −0.408 (−5.003, 4.188) | 0.862 | 0.095 | 64.1 |

| Other regions | 3 | −0.308 (−0.683, 0.068) | 0.108 | 0.927 | 0.0 |

| Funding | |||||

| Support by funding | 3 | −0.284 (−0.659, 0.092) | 0.139 | 0.530 | 0 |

| No-support by funding | 2 | −1.956 (−4.674, 0.763) | 0.159 | 0.572 | 0 |

3.4.3. Sensitivity Analyses

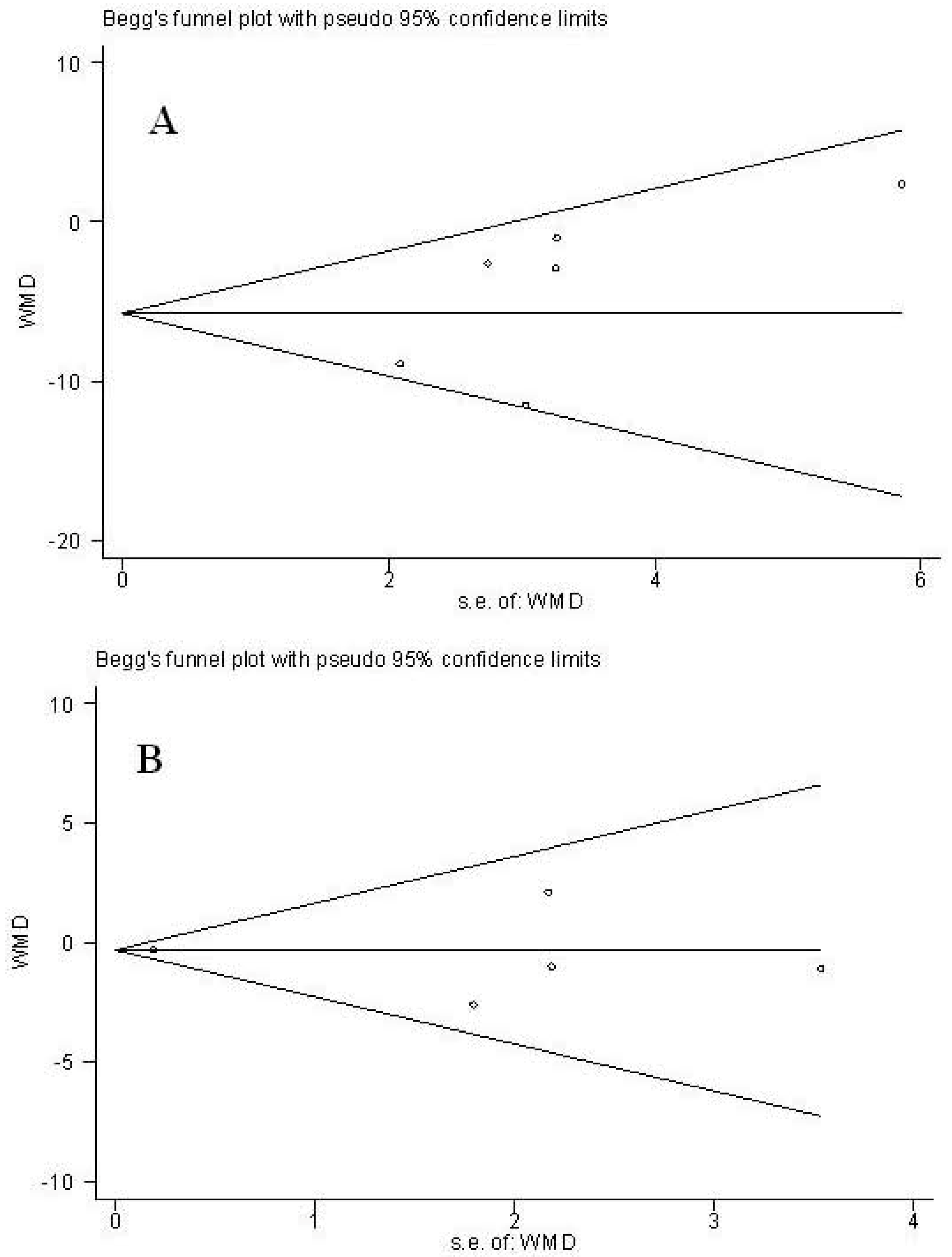

3.4.4. Publication Bias

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 1999 World Health Organization-International society of hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension. J. Hypertens. 1999, 17, 151–183.

- The sixth report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Arch. Intern. Med. 1997, 157, 2413–2446. [CrossRef]

- Widlansky, M.E.; Gokce, N.; Keaney, J.F., Jr.; Vita, J.A. The clinical implications of endothelial dysfunction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 42, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, D.; Desideri, G.; Ferri, L.; Aggio, A.; Tiberti, S.; Ferri, C. Oxidative stress endothelial dysfunction: Say NO to Cigarette Smoking! Curr. Pharm. Des. 2010, 16, 2539–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, E. Complementary/alternative medicine for hypertension: A mini-review. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2005, 155, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, G.Y.; Davis, R.B.; Phillips, R.S. Use of complementary therapies in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 2006, 98, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chobanian, A.V.; Bakris, G.L.; Black, H.R.; Cushman, W.C.; Green, L.A.; Izzo, J.L., Jr.; Jones, D.W.; Materson, B.J.; Oparil, S.; Wright, J.T., Jr.; et al. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: The JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003, 289, 2560–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetkey, L.P.; Simons-Morton, D.; Vollmer, W.M.; Appel, L.J.; Conlin, P.R.; Ryan, D.H.; Ard, J.; Kennedy, B.M. Effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure: Subgroup analysis of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) randomized clinical trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 1999, 15, 285–293. [Google Scholar]

- John, J.H.; Ziebland, S.; Yudkin, P.; Roe, L.S.; Neil, H.A. Effects of fruit and vegetable consumption on plasma antioxidant concentrations and blood pressure: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002, 359, 1969–1974. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, S.; Rao, A.V. Tomato lycopene and its role in human health and chronic diseases. CMAJ 2000, 163, 739–744. [Google Scholar]

- Bonetti, P.O.; Lerman, L.O.; Lerman, A. Endothelial dysfunction: A marker for atherosclerosis risk. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003, 23, 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Heber, D.; Lu, Q.Y. Overview of mechanisms of action of lycopene. Exp. Biol. Med. 2002, 227, 920–923. [Google Scholar]

- Engelhard, Y.N.; Gazer, B.; Paran, E. Natural antioxidants from tomato extract reduce blood pressure in patients with grade-1 hypertension: A double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Am. Heart J. 2006, 151, e1–e6. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.Y.; Paik, J.K.; Kim, O.Y.; Park, H.W.; Lee, J.H.; Jang, Y.; Lee, J.H. Effects of lycopene supplementation on oxidative stress and markers of endothelial function in healthy men. Atherosclerosis 2011, 15, 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Ried, K.; Frank, O.R.; Stocks, N.P. Dark chocolate or tomato extract for prehypertension: A randomised controlled trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2009, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paran, E.; Novack, V.; Engelhard, Y.N.; Hazan-Halevy, I. The effects of natural antioxidants from tomato extract in treated but uncontrolled hypertensive patients. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2009, 23, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hozawa, A.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Steffes, M.W.; Gross, M.D.; Steffen, L.M.; Lee, D.H. Circulating carotenoid concentrations and incident hypertension: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. J. Hypertens. 2009, 27, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itsiopoulos, C.; Brazionis, L.; Kaimakamis, M.; Cameron, M.; Best, J.D.; O’Dea, K.; Rowley, K. Can the Mediterranean diet lower HbA1c in type 2 diabetes? Results from a randomized cross-over study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2011, 21, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upritchard, J.E.; Sutherland, W.H.; Mann, J.I. Effect of supplementation with tomato juice, vitamin E, and vitamin C on LDL oxidation and products of inflammatory activity in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2000, 23, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, E.; Gordon, M.H.; Niwat, C.; George, T.W.; Parr, L.; Waroonphan, S.; Lovegrove, J.A. Supplementation with fruit and vegetable soups and beverages increases plasma carotenoid concentrations but does not alter markers of oxidative stress or cardiovascular risk factors. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 2849–2855. [Google Scholar]

- Ried, K.; Fakler, P. Protective effect of lycopene on serum cholesterol and blood pressure: Meta-analyses of intervention trials. Maturitas 2011, 68, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walfisch, Y.; Walfisch, S.; Agbaria, R.; Levy, J.; Sharoni, Y. Lycopene in serum, skin and adipose tissues after tomato-oleoresin supplementation in patients undergoing haemorrhoidectomy or peri-anal fistulotomy. Br. J. Nutr. 2003, 9, 759–766. [Google Scholar]

- Clinton, S.K. Lycopene: Chemistry, biology, and implications for human health and disease. Nutr. Rev. 1998, 56, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, W.; Schwarz, W.; Sundquist, A.R.; Sies, H. Cis–trans isomers of lycopene and beta-carotene in human serum and tissues. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1992, 29, 173–177. [Google Scholar]

- Rock, C.L.; Swendseid, M.E.; Jacob, R.A.; McKee, R.W. Plasma carotenoid levels in human subjects fed a low carotenoid diet. J. Nutr. 1992, 122, 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Thies, F.; Masson, L.F.; Rudd, A.; Vaughan, N.; Tsang, C.; Brittenden, J.; Simpson, W.G.; Duthie, S.; Horgan, G.W.; Duthie, G. Effect of a tomato-rich diet on markers of cardiovascular disease risk in moderately overweight, disease-free, middle-aged adults: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Green, S. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.0.2; The Cochrane Collboration: Oxford, England, 2009. Available online: www.cochrane-handbook.org (accessed on 25 October 2010).

- Stroup, D.F.; Berlin, J.A.; Morton, S.C.; Olkin, I.; Williamson, G.D.; Rennie, D.; Moher, D.; Becker, B.J.; Sipe, T.A.; Thacker, S.B. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2008, 283, 2008–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jadad, A.R.; Moore, R.A.; Carroll, D.; Jenkinson, C.; Reynolds, D.J.; Gavaghan, D.J.; McQuay, H.J. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin. Trials 1996, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DerSimonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin. Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Davey Smith, G.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluijs, I.; Beulens, J.W.; Grobbee, D.E.; van der Schouw, Y.T. Dietary carotenoid intake is associated with lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome in middle-aged and elderly men. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, A.S.; Macginley, R.J.; Schollum, J.B.; Williams, S.M.; Sutherland, W.H.; Mann, J.I.; Walker, R.J. Dietary sodium loading in normotensive healthy volunteers does not increase arterial vascular reactivity or blood pressure. Nephrology (Carlton) 2012, 17, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, A.S.; Macginley, R.J.; Schollum, J.B.; Johnson, R.J.; Williams, S.M.; Sutherland, W.H.; Mann, J.I.; Walker, R.J. Dietary salt loading impairs arterial vascular reactivity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, M.; Toyoshi, T.; Sano, A.; Izumi, T.; Fujii, T.; Konishi, C.; Inai, S.; Matsukura, C.; Fukuda, N.; Ezura, H.; et al. Antihypertensive effect of a gamma-aminobutyric acid rich tomato cultivar “DG03-9” in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centritto, F.; Iacoviello, L.; di Giuseppe, R.; de Curtis, A.; Costanzo, S.; Zito, F.; Grioni, S.; Sieri, S.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; et al. Dietary patterns, cardiovascular risk factors and C-reactive protein in a healthy Italian population. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2009, 19, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristenson, M.; Ziedén, B.; Kucinskienë, Z.; Elinder, L.S.; Bergdahl, B.; Elwing, B.; Abaravicius, A.; Razinkovienë, L.; Calkauskas, H.; Olsson, A.G. Antioxidant state and mortality from coronary heart disease in Lithuanian and Swedish men: Concomitant cross sectional study of men aged 50. BMJ 1997, 314, 629–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangborn, R.M.; Pecore, S.D. Taste perception of sodium chloride in relation to dietary intake of salt. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1982, 35, 510–520. [Google Scholar]

- Lauer, R.M.; Filer, L.J.; Reiter, M.A.; Clarke, W.R. Blood pressure, salt preference, salt threshold, and relative weight. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1976, 130, 493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Guo, H.; Wu, M.; Liu, M. Serum and dietary antioxidant status is associated with lower prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in a study in Shanghai, China. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 22, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Karppi, J.; Laukkanen, J.A.; Sivenius, J.; Ronkainen, K.; Kurl, S. Serum lycopene decreases the risk of stroke in men: A population-based follow-up study. Neurology 2012, 79, 1540–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.B.; Kumar, A.; Malhotra, M.; Arora, R.; Prasad, S.; Batra, S. Effect of lycopene on pre-eclampsia and intra-uterine growth retardation in primigravidas. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2003, 81, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Xu, J. Lycopene Supplement and Blood Pressure: An Updated Meta-Analysis of Intervention Trials. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3696-3712. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5093696

Li X, Xu J. Lycopene Supplement and Blood Pressure: An Updated Meta-Analysis of Intervention Trials. Nutrients. 2013; 5(9):3696-3712. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5093696

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xinli, and Jiuhong Xu. 2013. "Lycopene Supplement and Blood Pressure: An Updated Meta-Analysis of Intervention Trials" Nutrients 5, no. 9: 3696-3712. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5093696

APA StyleLi, X., & Xu, J. (2013). Lycopene Supplement and Blood Pressure: An Updated Meta-Analysis of Intervention Trials. Nutrients, 5(9), 3696-3712. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5093696