Focus on Vitamin D, Inflammation and Type 2 Diabetes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Inflammation, Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes

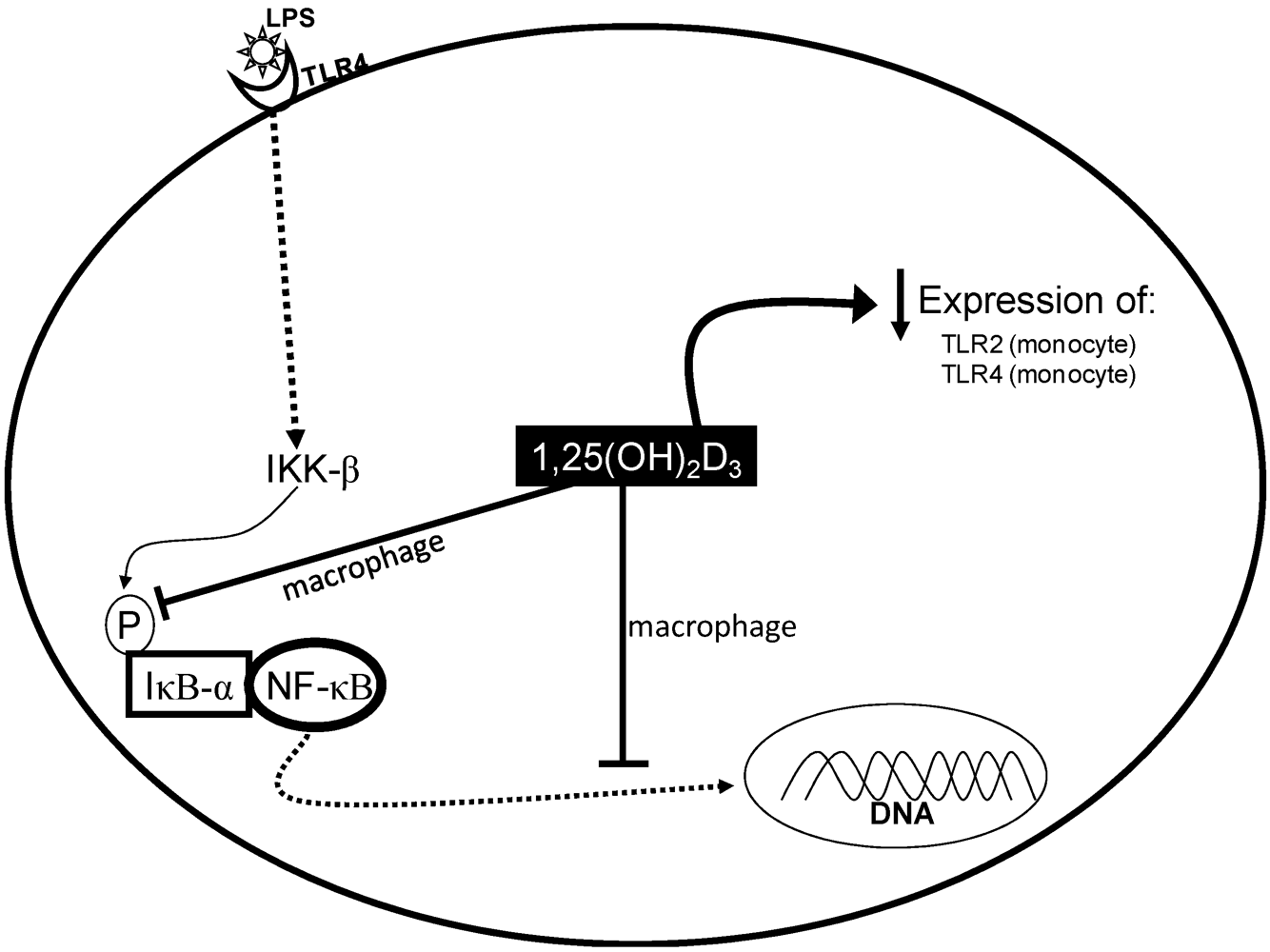

3. Vitamin D and Inflammation

| Ref. | Number and characteristics of subjects | Intervention and duration | Vitamin D effect on inflammatory serum biomarkers |

|---|---|---|---|

| [10] | 81 South Asian women with insulin resistance. Median serum 25OHD at baseline: 21 nmol/L. | 100 μg of vitamin D3 or placebo for 6 months. | No effect on C-reactive protein. |

| [47] | 123 patients with congestive heart failure. Mean serum 25OHD at the baseline: 36 nmol/L. | Oral supplementation (50 μg/day vitamin D3 plus 500 mg of calcium) for 9 months. | No differences in TNF-α and C-reactive protein. Significant increase in interleukin 10. |

| [48] | 34 haemodialysis patients. Mean serum 25OHD at baseline: not reported. | Oral (0.5 μg/day; n = 18) or intravenous (1 μg 3× week; n = 16) calcitriol for 6 months. | Oral calcitriol: No differences in TNF-α, interleukin 1 and interleukin 6; |

| Intravenous calcitriol: significant decrease in TNF-α, interleukin 1 and interleukin 6. | |||

| [49] | 70 post-menopausal women with osteoporosis. Mean serum 25OHD at baseline: not reported. | 0.5 μg/day of calcitriol and 1,000 mg/day of calcium or placebo (only 1,000 mg/day of calcium) for 6 months. | Significant decrease in decrease in TNF-α and interleukin 1. No differences in interleukin 6. |

| [50] | 222 non-obese subjects with normal fasting glucose and 92 non-obese with impaired fasting glucose. Mean serum 25OHD at baseline in both groups: 76 nmol/L. | 700 IU of vitamin D3 or placebos for 3 years. | No differences in C-reactive protein and interleukin 6. |

| [51] | 200 healthy overweight subjects. Mean serum 25OHD at baseline: 30 nmol/L. | 83 μg/day of vitamin D3 or placebo in a double-blind manner for 1 year while participation in a weight-reduction program. | More pronounced decrease in TNF-α in vitamin D group than in placebo group. |

| [52] | 218 long-term inpatients. Mean serum 25OHD at baseline: 23 nmol/L. | 0, 400 or 1200 IU/day of vitamin D3 for 6 months. | No differences in C-reactive protein. |

| [53] | 125 haemodialysis patients. Mean serum 25OHD at baseline: 32 nmol/L. | 100,000 IU/month of vitamin D3 for 15 months. | No differences in C-reactive protein. |

| [54] | 158 haemodialysis patients. Thirty-nine had diabetes and 54 had hypertension. Mean serum 25OHD at baseline: 55.75 nmol/L. | Vitamin D3 for 6 months according to 25OHD serum levels at the baseline: | Significant decrease in C-reactive protein. |

| - 50,000 IU/week for those with 25OHD serum levels < 15 ng/mL; | |||

| - 10,000 IU/week for those with 25OHD between 16 and 30 ng/mL; | |||

| - 2,700 IU 3x week for those with 25OHD > 30 ng/mL. | |||

| [55] | 30 haemodialysis patients. Mean serum 25OHD at baseline: 45.5 nmol/L. | Weekly supplementation of vitamin D3 for 24 weeks: 50,000 IU in the first 12 weeks and 20,000 IU in the last 12 weeks. | Significant decrease in C-reactive protein and interleukin 6. |

4. Vitamin D and Type 2 Diabetes

| Ref. | Study design | Subjects included | Main outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| [62] | Cohort (Mini-Finland Health Survey) | 4097 individuals followed-up for 17 years. | The highest versus the lowest serum 25OHD: RR = 0.70; 95% CI = 0.42–1.16); p for trend = 0.07). |

| [63] | Cohort (Tromsø Study) | 4157 non-smokers and 1962 smokers followed-up for 11 years. | Baseline serum 25OHD was inversely associated with type 2 diabetes. |

| [64] | Cohort (Nurses’ Health Study) | 83,779 women followed-up for 20 years. | The highest versus the lowest category of vitamin D intake from supplements: RR = 0.87; 95% CI = 0.75–1.00; p for trend = 0.004). |

| [65] | Nested case-control | 412 cases and 986 controls. | The highest versus the lowest quartiles of serum 25OHD: OR = 0.28 (95% CI = 0.10–0.81) in men and OR = 1.14 (95% CI = 0.60–2.17) in women. |

| [66] | Meta-analysis | Polled data from 2 cohorts studies with 8627 individuals aged 40–79 years. | The highest versus the lowest serum 25OHD: RR = 0.66; 95% CI = 0.50–0.87. |

| [67] | Cohort (Framingham Study) | 3066 (1402 men and 1664 women) followed-up for 7 years. | A higher 25OHD serum levels is associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes. |

| [6] | Nested case-control | 608 cases and 559 controls. | The highest versus the lowest serum 25OHD quartile: OR = 0.52; 95% CI = 0.33–0.83. |

| [68] | Cross-sectional | 210 individual aged more than 40. | Vitamin D deficiency was more common in diabetic compared to control. |

| [69] | Cross-sectional | 668 individuals aged 70–74 years. | Serum 25OHD < 50 nmol/L doubled the risk of newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. |

| [70] | Cohort (AusDiab study) | 5200 individuals; mean age 51 years. | Each 25 nmol/L increment in serum 25OHD was associated with a 24% reduced risk of type 2 diabetes (OR = 0.76; 95% CI = 0.63–0.92). |

| [71] | Cross-sectional | 2465 subjects. | Serum 25OHD ≥ 80 nmol/L versus ≤37 nmol/L in Caucasians: OR = 0.5; 95% CI = 0.1–0.7. |

| [9] | Systematic review of 7 observational cohort studies. | 238,424 individuals aged 30–75 years. | Vitamin D intake >500 versus <200 UI: risk of type 2 diabetes 13% lower. Serum 25OHD level (>25 ng/mL versus <14 ng/mL): risk of type 2 diabetes 43% lower. |

5. Conclusion

Acknowledgements

References

- International Diabetes Federation (IDF). Diabetes Atlas Global Burden, Epidemiology and Morbidity. Diabetes and Impaired Glucose Tolerance. Available online: http://www.diabetesaltas.org/content/diabetes-and-impaired-glucose-tolerance (acessed on 19 October 2011).

- James, W.P.T. 22nd Marabou Symposium: The changing faces of vitamin D. Nutr. Rev. 2008, 66, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melamed, M.L.; Michos, E.D.; Post, W.; Astor, B. 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and the risk of mortality in the general population. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 629–637. [Google Scholar]

- Palomer, X.; Gonzalez-Clemente, J.M.; Blanco-Vaca, F.; Mauricio, D. Role of vitamin D in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2008, 10, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, K.C.; Chu, A.; Go, V.L.; Saad, M.F. Hypovitaminosis D is associated with insulin resistance and beta cell dysfunction. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 820–825. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pittas, A.G.; Sun, Q.; Manson, J.E.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Hu, F.B. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration and risk of incident type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 2021–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorand, B.; Zierer, A.; Huth, C.; Linseisen, J.; Roden, M.; Peters, A.; Koenig, W.; Herder, C. Effect of serum 25-hydroxivitamin D on risk for type 2 diabetes may be partially mediated by subclinical inflammation: Results from the MONICA/RORA Ausburg study. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 2320–2322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pittas, A.; Dawson-Hughes, B. Vitamin D and diabetes. J. Sterol. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 121, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitri, J.; Murau, M.D.; Pittas, A.G. Vitamin D and type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 1005–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Hurst, P.R.; Stonehouse, W.; Coad, J. Vitamin D supplementation reduces insulin resistance in South Asian women living in New Zealand who are insulin resistant and vitamin D deficient—A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, A. Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, and Type 2 Diabetes: Inflammatory Basis of Glucose Metabolic Disorders. Nutr. Rev. 2007, 65, S152–S156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, M. A role of vitamin D in low-intensity chronic inflammation and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus? Nutr. Res. Rev. 2005, 18, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotamisligil, G.S.; Shargill, N.S.; Spiegelman, B.M. Adipose expression of tumor-necrosis-factor-alpha—direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science 1993, 259, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cancello, R.; Clement, K. Is obesity an inflammatory illness? Role of low-grade inflammation and macrophage infiltration in human white adipose tissue. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2006, 113, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumeng, C.N.; DeYoung, S.M.; Bodzin, J.L.; Saltiel, A.R. Increased inflammatory properties of adipose tissue macrophages recruited during diet-induced obesity. Diabetes 2007, 56, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumeng, C.N.; Bodzin, J.L.; Saltiel, A.R. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J. Clin. Invest. 2007, 117, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregor, M.F.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 29, 415–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeyda, M.; Stulnig, T.M. Obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance—a mini-review. Gerontology 2009, 55, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arkan, M.C.; Hevener, A.L.; Greten, F.R.; Maeda, S.; Li, Z.W.; Long, J.M.; Wynshaw-Boris, A.; Poli, G.; Olefsky, J.; Karin, M. IKK-beta links inflammation to obesity-induced insulin resistance. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Solinas, G.; Vilcu, C.; Neels, J.G.; Bandyopadhyay, G.K.; Luo, J.L.; Naugler, W.; Grivennikov, S.; Wynshaw-Boris, A.; Scadeng, M.; Olefsky, J.M.; Karin, M. JNK1 in hematopoietically derived cells contributes to diet-induced inflammation and insulin resistance without affecting obesity. Cell Metab. 2007, 6, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebrun, P.; Van Obberghen, E. SOCS proteins causing trouble in insulin action. Acta Physiol. 2008, 192, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Leal, F.L.; Fonseca-Alaniz, M.H.; Rogero, M.M.; Tirapegui, J. The role of inflamed adipose tissue in the insulin resistance. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2010, 28, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, A.; Martinez, K.; Chuang, C.C.; LaPoint, K.; McIntosh, M. Saturated fatty acid-mediated inflammation and insulin resistance in adipose tissue: Mechanisms of action and implications. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bruun, J.M.; Lihn, A.S.; Verdich, C.; Pedersen, S.B.; Toubro, S.; Astrup, A.; Richelsen, B. Regulation of adiponectin by adipose tissue-derived cytokines: In vivo and in vitro investigations in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 285, E527–E533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wolf, A.M.; Wolf, D.; Rumpold, H.; Enrich, B.; Tilg, H. Adiponectin induces the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and IL-1RA in human leukocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 323, 630–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, L.A.; Wood, R.J. Vitamin D status and the metabolic syndrome. Nutr. Rev. 2006, 64, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haussler, M.R.; Haussler, C.A.; Bartik, L.; Whitfield, G.K.; Hsieh, J.C.; Slater, S.; Jurutka, P.W. Vitamin D receptor: Molecular signaling and actions of nutritional ligands in disease prevention. Nutr. Rev. 2008, 66, S98–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigmundsdottir, H.; Pan, J.; Debes, G.F.; Alt, C.; Habtezion, A.; Soler, D.; Butcher, E.C. DCs metabolize sunlight-induced vitamin D3 to “program” T cell attraction to the epidermal chemokine CCL27. Nat. Immunol. 2007, 8, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritsche, J.; Mondal, K.; Ehrnsperger, A.; Andreesen, R.; Kreutz, M. Regulation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D-3-1 alpha-hydroxylase and production of 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-3 by human dendritic cells. Blood 2003, 102, 3314–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Etten, E.; Mathieu, C. Immunoregulation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-3: Basic concepts. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005, 97, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.T.; Stenger, S.; Li, H.Y.; Wenzel, L.; Tan, B.H.; Krutzik, S.R.; Ochoa, M.T.; Schauber, J.; Wu, K.; Meinken, C.; et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science 2006, 311, 1770–1773. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baker, R.G.; Hayden, M.S.; Ghosh, S. NF-kappa B, inflammation, and metabolic disease. Cell Metab. 2011, 13, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Lahav, M.; Shany, S.; Tobvin, D.; Chaimovitz, C.; Douvdevani, A. Vitamin D decreases NF kappa B activity by increasing I kappa B alpha levels. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2006, 21, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, K.; Wessner, B.; Laggner, U.; Ploder, M.; Tamandl, D.; Friedl, J.; Zügel, U.; Steinmeyer, A.; Pollak, A.; Roth, E.; et al. Vitamin D3 down-regulates monocyte TLR expression and triggers hyporesponsiveness to pathogen-associated molecular patterns. Eur. J. Immunol. 2006, 36, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giulietti, A.; van Etten, E.; Overbergh, L.; Stoffels, K.; Bouillon, R.; Mathieu, C. Monocytes from type 2 diabetic patients have a pro-inflammatory profile—1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D-3 works as anti-inflammatory. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2007, 77, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Lahav, M.; Douvdevani, A.; Chaimovitz, C.; Shany, S. The anti-inflammatory activity of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-3 in macrophages. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007, 103, 558–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, M.C.; Martini, L.A.; Rogero, M.M. Current perspectives on vitamin D, immune system, and chronic diseases. Nutrition 2011, 27, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jablonski, K.L.; Chonchol, M.; Pierce, G.L.; Walker, A.E.; Seals, D.R. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D deficiency is associated with inflammation-linked vascular endothelial dysfunction in middle-aged and older adults. Hypertension 2011, 57, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, C.A.; Heffernan, M.E. Serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha concentrations are negatively correlated with serum 25(OH)D concentrations in healthy women. J. Inflam. 2008, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, D.T.; Sverdlov, A.L.; McNeil, J.J.; Horowitz, J.D. Does Vitamin D modulate asymmetric dimethylarginine and C-reactive protein concentrations? Am. J. Med. 2010, 123, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobnig, H.; Pilz, S.; Scharnagl, H.; Renner, W.; Seelhorst, U.; Wellnitz, B.; Kinkeldei, J.; Boehm, B.O.; Weihrauch, G.; Maerz, W. Independent association of low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 1340–1349. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bellia, A.; Garcovich, C.; D’Adamo, M.; Lombardo, M.; Tesauro, M.; Donadel, G.; Gentileschi, P.; Lauro, D.; Federici, M.; Lauro, R.; et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels are inversely associated with systemic inflammation in severe obese subjects. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganji, V.; Zhang, X.; Shaikh, N.; Tangpricha, V. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations are associated with prevalence of metabolic syndrome and various cardiometabolic risk factors in US children and adolescents based on assay-adjusted serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D data from NHANES 2001–2006. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyppoenen, E.; Berry, D.; Cortina-Borja, M.; Power, C. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and Pre-Clinical Alterations in Inflammatory and Hemostatic Markers: A Cross Sectional Analysis in the 1958 British Birth Cohort. PLoS One 2010, 5, e10801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jorde, R.; Haug, E.; Figenschau, Y.; Hansen, J.B. Serum levels of vitamin D and haemostatic factors in healthy subjects: The Tromso study. Acta Haemat. 2007, 117, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilarrasa, N.; Vendrell, J.; Maravall, J.; Elio, I.; Solano, E.; San Jose, P.; García, I.; Virgili, N.; Soler, J.; Gómez, J.M. Is plasma 25(OH) D related to adipokines, inflammatory cytokines and insulin resistance in both a healthy and morbidly obese population? Endocrine 2010, 38, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleithoff, S.S.; Zittermann, A.; Tenderich, G.; Berthold, H.K.; Stehle, P.; Koerfer, R. Vitamin D supplementation improves cytokine profiles in patients with congestive heart failure: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 754–759. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Borazan, A.; Ustun, H.; Cefle, A.; Sekitmez, N.; Yilmaz, A. Comparative efficacy of oral and intravenous calcitriol treatment in haemodialysis patients: Effects on serum biochemistry and cytokine levels. J. Int. Med. Res. 2003, 31, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Inanir, A.; Ozoran, K.; Tutkak, H.; Mermerci, B. The effects of calcitriol therapy on serum interleukin-1, interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha concentrations in post-menopausal patients with osteoporosis. J. Int. Med. Res. 2004, 32, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pittas, A.G.; Harris, S.S.; Stark, P.C.; Dawson-Hughes, B. The effects of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on blood glucose and markers of inflammation in nondiabetic adults. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zittermann, A.; Frisch, S.; Berthold, H.K.; Goetting, C.; Kuhn, J.; Kleesiek, K.; Stehle, P.; Koertke, H.; Koerfer, R. Vitamin D supplementation enhances the beneficial effects of weight loss on cardiovascular disease risk markers. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1321–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjorkman, M.P.; Sorva, A.J.; Tilvis, R.S. C-reactive protein and fibrinogen of bedridden older patients in a six-month vitamin D supplementation trial. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2009, 13, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jean, G.; Souberbielle, J.-C.; Chazot, C. Monthly cholecalciferol administration in haemodialysis patients: A simple and efficient strategy for vitamin D supplementation. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009, 24, 3799–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matias, P.J.; Jorge, C.; Ferreira, C.; Borges, M.; Aires, I.; Amaral, T.; Gil, C.; Crtez, J.; Ferreira, A. Cholecalciferol supplementation in hemodialysis patients: Effects on mineral metabolism, inflammation, and cardiac dimension parameters. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 5, 905–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucharles, S.; Barberato, S.R.; Stinghen, A.E.M.; Gruber, B.; Piekala, L.; Dambiski, A.C.; Custodio, M.R.; Pecoits-Filho, R. Impact of cholecalciferol treatment on biomarkers of inflammation and myocardial structure in hemodialysis patients without hyperparathyroidism. J. Ren. Nutr. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takiishi, T.; Gysemans, C.; Bouillon, R.; Mathieu, C. Vitamin D and diabetes. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 39, 419–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolden-Kirk, H.; Overbergh, L.; Christesen, H.T.; Brusgaard, K.; Mathieu, C. Vitamin D and diabetes: Its importance for beta cell and immune function. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2011, 347, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, A.W.; Frnkel, J.B.; Heldt, A.M.; Grodsky, G.M. Vitamin D deficency inhibits pancreatic secretion of insulin. Science 1980, 209, 823–825. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cade, C.; Norman, A.W. Rapid normalization/stimulation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 of insulin secretion and glucose tolerance in the vitamin D-deficent rat. Endocrinology 1987, 120, 1490–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, I.T.; Jarrett, R.J.; Keen, H. Diurnal and seasonal variation in oral glucose tolerance: Studies in the Antartic. Diabetologia 1975, 11, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behall, K.M.; Scholfield, D.J.; Hallfrisch, J.G.; Kelsay, J.L.; Reiser, S. Seasonal variation in plasma glucose and hormone levels in adult men and women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1984, 40, 1352–1356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mattila, C.; Knekt, P.; Männistö, S.; Rissanen, H.; Laaksonen, M.A.; Montonen, J.; Reunanen, A. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration and subsequent risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 2569–2570. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grimnes, G.; Emaus, N.; Joakimsen, R.M.; Figenschau, Y.; Jenssen, T.; Njølstad, I.; Schirmer, H.; Jorde, R. Baseline serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in the Tromsø Study 1994–95 and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus during 11 years of follow up. Diabet. Med. 2010, 27, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittas, A.G.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Li, M.; Van Dam, R.M.; Willett, W.C.; Manson, J.E.; Hu, F.B. Vitamin D and calcium intake in relation to type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Knekt, P.; Laaksonen, M.; Mattila, C.; Härkänen, T.; Marniemi, J.; Heliövaara, M.; Rissanen, H.; Montonen, J.; Reunanen, A. Serum vitamin D and subsequent occurrence of type 2 diabetes. Epidemiology 2008, 19, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laaksonen, M.A.; Knekt, P.; Rissanen, H.; Härkanen, T.; Virtala, E.; Marniemi, J.; Aromaa, A.; Heliövaara, M.; Reunane, A. The relative importance of modifiable potential risk factors of type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of two cohorts. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 25, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, E.; Meigs, J.B.; Pittas, A.G.; Economos, C.D.; Mckeown, N.M.; Booth, S.L.; Jacques, P.F. Predicted 25-hydroxyvitamin D score and incident type 2 diabetes in the Framingham offspring study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1627–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahrani, A.A.; Ball, A.; Shepherd, L.; Rahim, A.; Jones, A.F.; Bates, A. The prevalence of vitamin D abnormalities in South Asians with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the UK. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2010, 64, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalgard, C.; Petersen, M.S.; Weihe, P.; Grandjean, P. Vitamin D status in relation to glucose metabolism and type 2 diabetes in septuagenarians. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 1284–1288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gagnon, C.; Lu, Z.X.; Magliano, D.J.; Dunstan, D.W.; Shaw, J.E.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Sikaris, K.; Grantham, N.; Ebeling, P.R.; Daly, R.M. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, calcium intake, and risk of type 2 diabetes after 5 years. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 1133–1138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brock, K.E.; Huang, W.Y.; Fraser, D.R.; Ke, L.; Tseng, M.; Mason, R.S.; Stolzenberg-Solomon, R.Z.; Freedman, D.M.; Ahn, J.; Peters, U.; et al. Diabetes prevalence is associated with serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in US middle-aged Caucasians men and women: A cross-sectional analysis within the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 106, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mitri, J.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Hu, F.B.; Pittas, A.G. Effects of vitamin D and calcium supplementation od pancreatic β cell function, insulin sensitivity, and glycemia in adults at high risk of diabetes: The Calcium and Vitamin D for Diabetes Mellitus (CaDDM) randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikooyeh, B.; Neyestani, T.R.; Farvid, M.; Alavi-Majd, H.; Houshiarrad, A.; Kalayi, A.; Shariatzadeh, N.; Gharavi, A.; Heravifard, S.; Tayebinejad, N.; et al. Daily consumption of vitamin D- or vitamin D + calcium-fortified yogurt drink improved glycemic conrol in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witham, M.D.; Dove, F.J.; Dryburgh, M.; Sygden, J.A.; Morris, A.D.; Struthers, A.D. The effect of different doses of vitamin D3 on markers of vascular health in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 2010, 53, 2112–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittas, A.G.; Lau, J.; Hu, F.B.; Dawson-Hughes, B. The role of vitamin D and calcium in type 2 diabetes. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 92, 2017–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittas, A.G.; Chung, M.; Trikalinos, T.; Mitri, J.; Brendel, M.; Patel, K.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Lau, J.; Balk, E.M. Systematic review: vitamin D and cardiometabolic outcomes. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 152, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baier, L.J.; Dobberfuhl, A.A.; Pratley, R.E.; Hanson, R.L.; Bogardus, C. Variations in the vitamin D-binding protein (Gc locus) are associated with oral glucose tolerance in nondiabetic Pima Indians. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998, 83, 2993–2996. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hirai, M.; Suzuki, S.; Hinokio, Y.; Chiba, M.; Akai, H.; Suzuki, C.; Toyota, T. Variations in vitamin D-binding protein (group-specific component protein) are associated with fasting plasma insulin levels in Japanese with normal glucose tolerance. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 1951–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klupa, T.; Malecki, M.; Hanna, L.; Sieradzka, J.; Frey, J.; Warram, J.H.; Sieradzki, J.; Krolewski, A.S. Amino acid variats of the vitamin D-binding protein and risk of diabetes in white Americans of European origin. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 1999, 141, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, W.Z.; Dubois-Laforgue, D.; Bellanné-Chantelot, C.; Timsit, J.; Velho, G. Variations in the vitamin D-biding protein (Gc locus) and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in French Caucasians. Metabolism 2001, 50, 366–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.Y.; Barrett-Connor, E. Association between vitamin D receptor polymorphism and type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome in community-dwelling older adults: The Rancho Bernardo Study. Metabolism 2002, 51, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bid, H.K.; Konwasr, R.; Aggarwal, C.G.; Gautam, S.; Saxena, M.; Nayak, V.L.; Banerjee, M. Vitamin D receptor (FolkI, BsmI and TaqI) gene polymorphisms and type 2 diabetes mellitus: A North Indian study. Indian J. Med. Sci. 2009, 63, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhopadhyaya, P.N.; Acharya, A.; Chavan, Y.; Purohit, S.S.; Mutha, A. Metagenomic study of single-nucleotide polymorphisms within cadidate genes associated with type 2 diabetes in an Indian population. Genet. Mol. Res. 2010, 9, 2060–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malecki, M.T.; Frey, J.; Moczulshi, D.; Klupa, T.; Kozek, E.; Sieradzki, J. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and association with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a Polish population. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2003, 111, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilmec, F.; Uzer, E.; Akkafa, F.; Kose, E.; Van Kuilenburg, A.B. Detection of VDR gene ApaI and TaquI polymorphisms in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus using PCR-RFLP method in Turkish population. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2010, 24, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Chagas, C.E.A.; Borges, M.C.; Martini, L.A.; Rogero, M.M. Focus on Vitamin D, Inflammation and Type 2 Diabetes. Nutrients 2012, 4, 52-67. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu4010052

Chagas CEA, Borges MC, Martini LA, Rogero MM. Focus on Vitamin D, Inflammation and Type 2 Diabetes. Nutrients. 2012; 4(1):52-67. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu4010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleChagas, Carlos Eduardo Andrade, Maria Carolina Borges, Lígia Araújo Martini, and Marcelo Macedo Rogero. 2012. "Focus on Vitamin D, Inflammation and Type 2 Diabetes" Nutrients 4, no. 1: 52-67. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu4010052

APA StyleChagas, C. E. A., Borges, M. C., Martini, L. A., & Rogero, M. M. (2012). Focus on Vitamin D, Inflammation and Type 2 Diabetes. Nutrients, 4(1), 52-67. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu4010052