Taste Changes in a Rat Model of Spinal Cord Injury: Impact of High-Fat Diet and Weight Loss Surgery

Abstract

1. Introduction

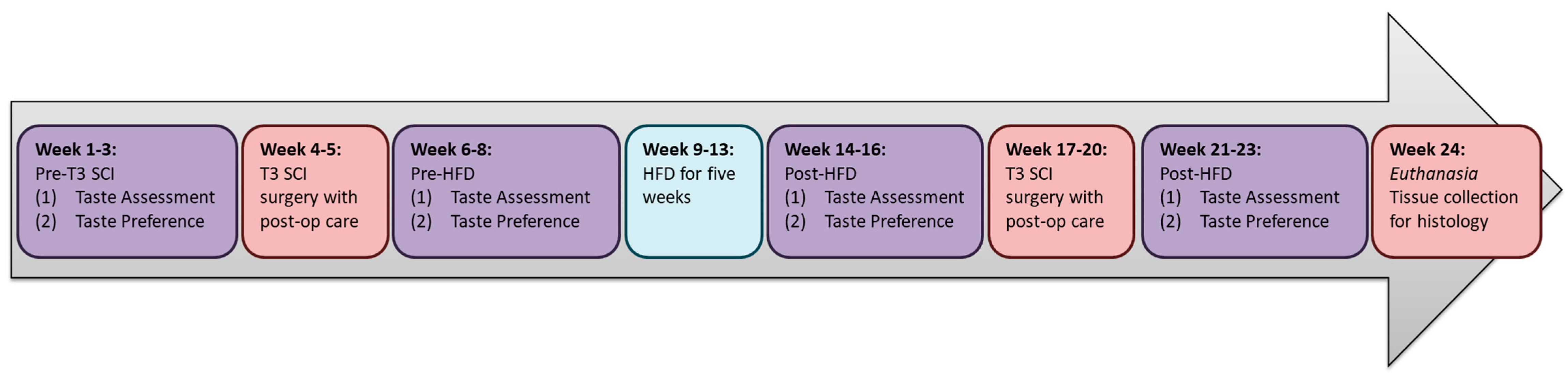

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Taste Responsivity Following SCI

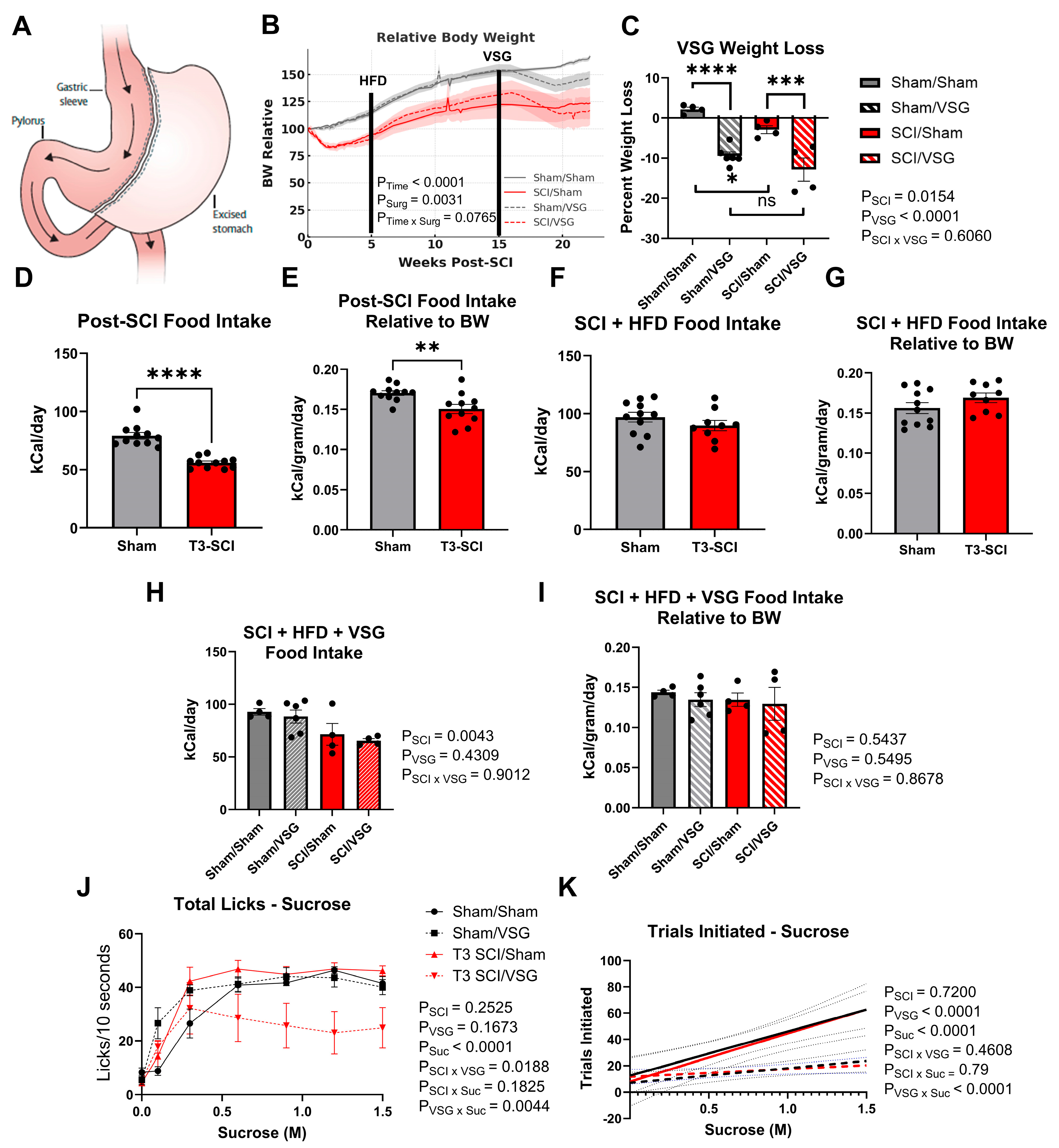

3.2. Body Weight Following VSG

3.3. Taste Responsivity Following VSG

3.4. Long-Access Sucrose Preference

3.5. DVC Activation Following Sucrose Consumption

4. Discussion

4.1. SCI Alters Taste Responsivity

4.2. HFD Amplifies Sweet Taste Responsivity and Masks Some SCI Effects

4.3. VSG Suppresses Sweet-Motivated Behavior While Enhancing DVC Activation

4.4. Neuroplasticity After Spinal Cord Injury

4.5. Clinical and Translational Implications

4.6. Limitations

4.7. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCI | Spinal cord injury |

| VSG | Vertical sleeve gastrectomy |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

| DVC | Dorsal vagal complex |

| 2BC | Two-bottle choice test |

| NTS | Nucleus of the solitary tract |

| CGRP | Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide |

| GLP1 | Glucagon-like Peptide 1 |

| GLP1-RA | Glucagon-like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonist |

| BMI | Body mass index |

References

- National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. SCIfacts figures 2016. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2016, 39, 737–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central][Green Version]

- Gorgey, A.S.; Dolbow, D.R.; Dolbow, J.D.; Khalil, R.K.; Castillo, C.; Gater, D.R. Effects of spinal cord injury on body composition and metabolic profile—Part I. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2014, 37, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gorgey, A.S.; Gater, D.R., Jr. Prevalence of Obesity After Spinal Cord Injury. Top. Spinal Cord Inj. Rehabil. 2007, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gupta, N.; White, K.T.; Sandford, P.R. Body mass index in spinal cord injury—A retrospective study. Spinal Cord 2006, 44, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shojaei, M.H.; Alavinia, S.M.; Craven, B.C. Management of obesity after spinal cord injury: A systematic review. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2017, 40, 783–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Duckworth, W.C.; Jallepalli, P.; Solomon, S.S. Glucose intolerance in spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1983, 64, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bauman, W.A.; Spungen, A.M. Carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in chronic spinal cord injury. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2001, 24, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundy, S.M.; Brewer, H.B., Jr.; Cleeman, J.I.; Smith, S.C., Jr.; Lenfant, C.; National Heart, Lung; Blood Institute; American Heart Association. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, e13–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angrisani, L.; Santonicola, A.; Iovino, P.; Vitiello, A.; Zundel, N.; Buchwald, H.; Scopinaro, N. Bariatric Surgery and Endoluminal Procedures: IFSO Worldwide Survey 2014. Obes. Surg. 2017, 27, 2279–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noguchi, T.; Katoh, H.; Nomura, S.; Okada, K.; Watanabe, M. The GLP-1 receptor agonist exenatide improves recovery from spinal cord injury by inducing macrophage polarization toward the M2 phenotype. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1342944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- LaVela, S.L.; Berryman, K.; Kale, I.; Farkas, G.J.; Henderson, G.V.; Rosales, V.; Eisenberg, D.; Reyes, L. Potential barriers to the use of anti-obesity medications in persons with spinal cord injuries and disorders. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2024, 10, e784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nakatani, Y.; Maeda, M.; Matsumura, M.; Shimizu, R.; Banba, N.; Aso, Y.; Yasu, T.; Harasawa, H. Effect of GLP-1 receptor agonist on gastrointestinal tract motility and residue rates as evaluated by capsule endoscopy. Diabetes Metab. 2017, 43, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, G.M.; Blanke, E.N. Gastrointestinal dysfunction after spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 2019, 320, 113009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Blanke, E.N.; Holmes, G.M. Dysfunction of pancreatic exocrine secretion after experimental spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 2025, 389, 115257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layton, G.R.; Bhanderi, S.; Sahloul, M.; Charalampakis, V.; Daskalakis, M.; Singhal, R. Challenges and outcomes for bariatric surgery in patients with paraplegia: Case series and systematic review. Clin. Obes. 2020, 10, e12382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orellana, E.R.; Covasa, M.; Hajnal, A. Neuro-hormonal mechanisms underlying changes in reward related behaviors following weight loss surgery: Potential pharmacological targets. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2019, 164, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makaronidis, J.M.; Batterham, R.L. Potential Mechanisms Mediating Sustained Weight Loss Following Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass and Sleeve Gastrectomy. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 45, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz, T.A.; Bueter, M. The physiology underlying Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: A status report. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2014, 307, R1275–R1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bueter, M.; Le Roux, C.W. Gastrointestinal hormones, energy balance and bariatric surgery. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, S35–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, C.S.; Berthoud, H.R.; Bueter, M.; Chakravarthy, M.V.; Geliebter, A.; Hajnal, A.; Holst, J.; Kaplan, L.; Pories, W.; Raybould, H.; et al. Could the mechanisms of bariatric surgery hold the key for novel therapies?: Report from a Pennington Scientific Symposium. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 984–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, A.P.; Paziuk, M.; Luevano, J.M., Jr.; Machineni, S.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Kaplan, L.M. Conserved shifts in the gut microbiota due to gastric bypass reduce host weight and adiposity. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 178ra41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Manning, S.; Pucci, A.; Batterham, R.L. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: Effects on feeding behavior and underlying mechanisms. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peiris, M.; Aktar, R.; Raynel, S.; Hao, Z.; Mumphrey, M.B.; Berthoud, H.R.; Blackshaw, L.A. Effects of Obesity and Gastric Bypass Surgery on Nutrient Sensors, Endocrine Cells, and Mucosal Innervation of the Mouse Colon. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nance, K.; Eagon, J.C.; Klein, S.; Pepino, M.Y. Effects of Sleeve Gastrectomy vs. Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass on Eating Behavior and Sweet Taste Perception in Subjects with Obesity. Nutrients 2017, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Halmi, K.A.; Mason, E.; Falk, J.R.; Stunkard, A. Appetitive behavior after gastric bypass for obesity. Int. J. Obes. 1981, 5, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brown, E.K.; Settle, E.A.; Van Rij, A.M. Food intake patterns of gastric bypass patients. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1982, 80, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arumugam, M.; Raes, J.; Pelletier, E.; Le Paslier, D.; Yamada, T.; Mende, D.R.; Fernandes, G.R.; Tap, J.; Bruls, T.; Batto, J.M.; et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 2011, 473, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Olbers, T.; Bjorkman, S.; Lindroos, A.; Maleckas, A.; Lonn, L.; Sjostrom, L.; Lonroth, H. Body composition, dietary intake, and energy expenditure after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and laparoscopic vertical banded gastroplasty: A randomized clinical trial. Ann. Surg. 2006, 244, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ochner, C.N.; Kwok, Y.; Conceição, E.; Pantazatos, S.P.; Puma, L.M.; Carnell, S.; Teixeira, J.; Hirsch, J.; Geliebter, A. Selective Reduction in Neural Responses to High Calorie Foods Following Gastric Bypass Surgery. Ann. Surg. 2011, 253, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, A.C.; Berthoud, H.R. Food reward functions as affected by obesity and bariatric surgery. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, S40–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hajnal, A.; Kovacs, P.; Ahmed, T.A.; Meirelles, K.; Lynch, C.J.; Cooney, R.N. Gastric bypass surgery alters behavioral and neural taste functions for sweet taste in obese rats. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2010, 299, G967–G979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morinigo, R.; Moize, V.; Musri, M.; Lacy, A.M.; Navarro, S.; Marin, J.L.; Delgado, S.; Casamitjana, R.; Vidal, J. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1, Peptide YY, Hunger, and Satiety after Gastric Bypass Surgery in Morbidly Obese Subjects. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 1735–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, G.M.; Willing, L.B.; Horvath, N.; Hajnal, A. Feasibility Study of Bariatric Surgery in a Rat Model of Spinal Cord Injury to Achieve Beneficial Body Weight Outcome. Neurotrauma Rep. 2022, 3, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mezei, G.C.; Ural, S.H.; Hajnal, A. Differential Effects of Maternal High Fat Diet During Pregnancy and Lactation on Taste Preferences in Rats. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Spector, A.C. Behavioral analyses of taste function and ingestion in rodent models. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 152, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Paxinos, G.; Watson, C.R.; Emson, P.C. AChE-stained horizontal sections of the rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. J. Neurosci. Methods 1980, 3, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyndaele, J.J. Multidisciplinary aspect of spinal cord medicine. Introduction Spinal Cord. 2008, 46, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, T. Neural mechanisms for the control of thirst and salt appetite in response to body fluid conditions and intake behavior. Neurosci. Res. 2025, 219, 104941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, G.; Oliveira-Maia, A.J. Sweet taste and obesity. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 92, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fernandes, A.B.; Alves da Silva, J.; Almeida, J.; Cui, G.; Gerfen, C.R.; Costa, R.M.; Oliveira-Maia, A.J. Postingestive Modulation of Food Seeking Depends on Vagus-Mediated Dopamine Neuron Activity. Neuron 2023, 111, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hogeveen, J.; Campbell, E.; Aragon, D.; Pearson, E.; Enders, C.; Romero, J.; Brown, L.; Campbell, R.A.; Gill, D.; Quinn, D.K.; et al. Blunted Reward Prediction Error Encoding Drives Diminished Motivation to Explore in Apathy Associated with Traumatic Brain Injury. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, A.R.; Cleveland, L.B. Olfaction and Chronic Spinal Cord Injury. J. Neurol. Rehabil. 1998, 12, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, D.J.; Bartoshuk, L.M. Oral sensory nerve damage: Causes and consequences. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2016, 17, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hill, D.L. Neural plasticity in the gustatory system. Nutr. Rev. 2004, 62, S208–S217, discussion S24–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Whitehead, M.C.; McGlathery, S.T.; Manion, B.G. Transganglionic degeneration in the gustatory system consequent to chorda tympani damage. Exp. Neurol. 1995, 132, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qualls-Creekmore, E.; Tong, M.; Holmes, G.M. Time-course of recovery of gastric emptying and motility in rats with experimental spinal cord injury. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2010, 22, 62-e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tong, M.; Holmes, G.M. Gastric dysreflexia after acute experimental spinal cord injury in rats. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2009, 21, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tong, M.; Qualls-Creekmore, E.; Browning, K.N.; Travagli, R.A.; Holmes, G.M. Experimental spinal cord injury in rats diminishes vagally-mediated gastric responses to cholecystokinin-8s. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2011, 23, e69–e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Besecker, E.M.; Blanke, E.N.; Deiter, G.M.; Holmes, G.M. Gastric vagal afferent neuropathy following experimental spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 2020, 323, 113092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Farkas, G.J.; Cunningham, P.M.; Sneij, A.M.; Hayes, J.E.; Nash, M.S.; Berg, A.S.; Gater, D.R.; Rolls, B.J. Reasons for meal termination, eating frequency, and typical meal context differ between persons with and without a spinal cord injury. Appetite 2024, 192, 107110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthoud, H.R.; Zheng, H.; Shin, A.C. Food reward in the obese and after weight loss induced by calorie restriction and bariatric surgery. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1264, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ballsmider, L.A.; Vaughn, A.C.; David, M.; Hajnal, A.; Di Lorenzo, P.M.; Czaja, K. Sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass alter the gut-brain communication. Neural Plast. 2015, 2015, 601985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Escanilla, O.D.; Hajnal, A.; Czaja, K.; Di Lorenzo, P.M. The Neural Code for Taste in the Nucleus of the Solitary Tract of Rats with Obesity Following Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hermann, G.E.; Kohlerman, N.J.; Rogers, R.C. Hepatic-vagal and gustatory afferent interactions in the brainstem of the rat. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1983, 9, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermann, G.E.; Rogers, R.C. Convergence of vagal and gustatory afferent input within the parabrachial nucleus of the rat. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1985, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamamah, S.; Hajnal, A.; Covasa, M. Influence of Bariatric Surgery on Gut Microbiota Composition and Its Implication on Brain and Peripheral Targets. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Orellana, E.; Horvath, N.; Farokhnia, M.; Leggio, L.; Hajnal, A. Changes in plasma ghrelin levels following surgical and non-surgical weight-loss in female rats predict alcohol use. Brain Res. Bull. 2022, 188, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filipp, M.E.; Travis, B.J.; Henry, S.S.; Idzikowski, E.C.; Magnuson, S.A.; Loh, M.Y.; Hellenbrand, D.J.; Hanna, A.S. Differences in neuroplasticity after spinal cord injury in varying animal models and humans. Neural Regen. Res. 2019, 14, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raineteau, O.; Schwab, M.E. Plasticity of motor systems after incomplete spinal cord injury. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 2, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, L.A.; Gustin, S.M.; Macey, P.M.; Wrigley, P.J.; Siddall, P.J. Functional reorganization of the brain in humans following spinal cord injury: Evidence for underlying changes in cortical anatomy. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 2630–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Calderone, A.; Cardile, D.; De Luca, R.; Quartarone, A.; Corallo, F.; Calabro, R.S. Brain Plasticity in Patients with Spinal Cord Injuries: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, Z.; Feng, K.; Huang, J.; Ye, X.; Yang, R.; Huang, Q.; Jiang, Q. Brain region changes following a spinal cord injury. Neurochem. Int. 2024, 174, 105696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Snyder, J.; Tang, T.; Holmes, G.M.; Hajnal, A. Taste Changes in a Rat Model of Spinal Cord Injury: Impact of High-Fat Diet and Weight Loss Surgery. Nutrients 2026, 18, 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030503

Snyder J, Tang T, Holmes GM, Hajnal A. Taste Changes in a Rat Model of Spinal Cord Injury: Impact of High-Fat Diet and Weight Loss Surgery. Nutrients. 2026; 18(3):503. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030503

Chicago/Turabian StyleSnyder, Jonathan, Tiffany Tang, Gregory M. Holmes, and Andras Hajnal. 2026. "Taste Changes in a Rat Model of Spinal Cord Injury: Impact of High-Fat Diet and Weight Loss Surgery" Nutrients 18, no. 3: 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030503

APA StyleSnyder, J., Tang, T., Holmes, G. M., & Hajnal, A. (2026). Taste Changes in a Rat Model of Spinal Cord Injury: Impact of High-Fat Diet and Weight Loss Surgery. Nutrients, 18(3), 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030503