Meat Consumption Associated with the Risk of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Methods

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Selected Studies

3.2. Characteristics of Studies

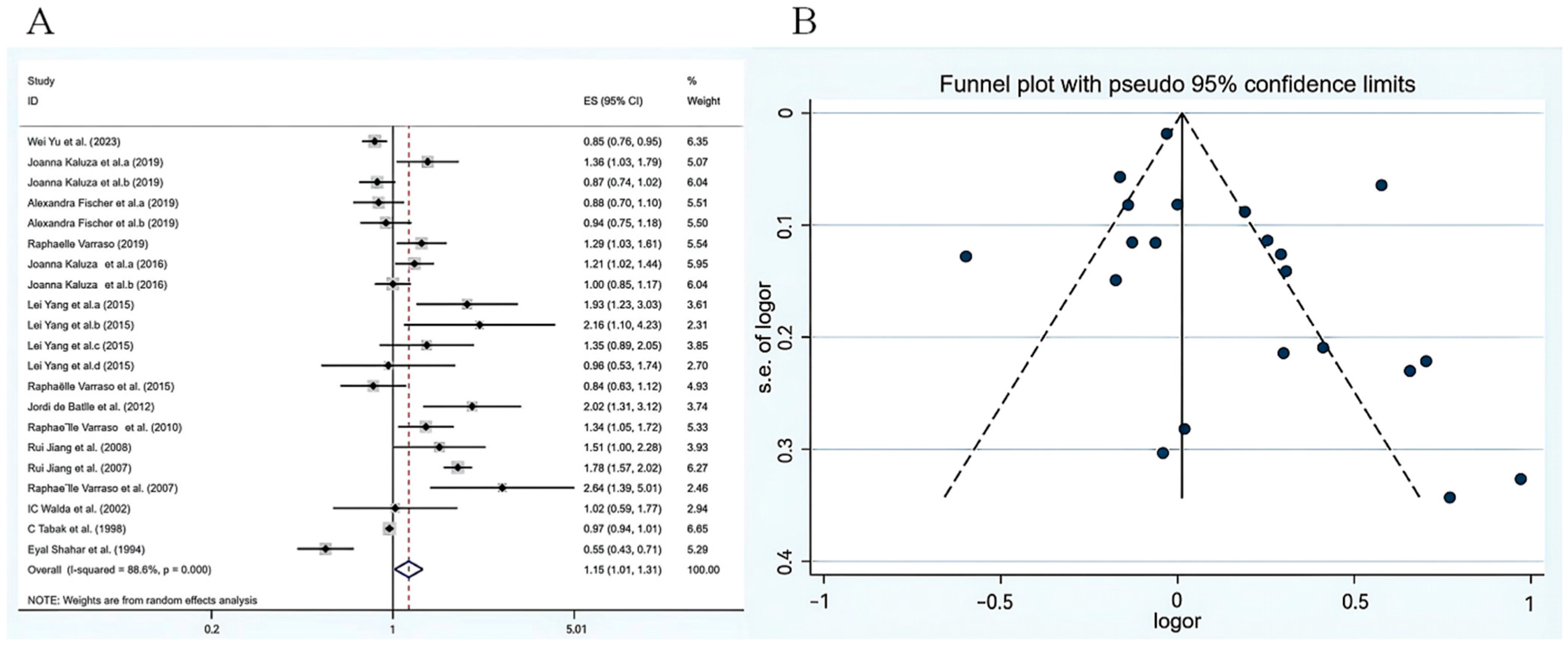

3.3. Total Meat Consumption and COPD Risk

3.4. Subgroup Analysis of the Effect of Meat Consumption on COPD Risk and Meta Regression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, I.A.; Jenkins, C.R.; Salvi, S.S. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in never-smokers: Risk factors, pathogenesis, and implications for prevention and treatment. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2100–2132. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boers, E.; Barrett, M.; Su, J.G.; Benjafield, A.V.; Sinha, S.; Kaye, L.; Zar, H.J.; Vuong, V.; Tellez, D.; Gondalia, R. Global Burden of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Through 2050. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2346598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtjer, J.C.S.; Bloemsma, L.D.; Beijers, R.J.H.C.G.; Cornelissen, M.E.B.; Hilvering, B.; Houweling, L.; Vermeulen, R.C.H.; Downward, G.S.; Maitland-Van der Zee, A.H.; P4O2 consortium. Identifying risk factors for COPD and adult-onset asthma: An umbrella review. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2023, 32, 230009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S.O.; Jameson, K.A.; Syddall, H.E.; Aihie Sayer, A.; Dennison, E.M.; Cooper, C.; Robinson, S.M. Hertfordshire Cohort Study Group. The relationship of dietary patterns with adult lung function and COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2010, 36, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, F.B. Dietary pattern analysis: A new direction in nutritional epidemiology. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2002, 13, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedi Fard, M.; Mohammadhasani, K.; Dehnavi, Z.; Khorasanchi, Z. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: The Role of Healthy and Unhealthy Dietary Patterns-A Comprehensive Review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 9875–9892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeever, T.M.; Lewis, S.A.; Cassano, P.A.; Ocké, M.; Burney, P.; Britton, J.; Smit, H.A. Patterns of dietary intake and relation to respiratory disease, forced expiratory volume in 1 s, and decline in 5-y forced expiratory volume. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.F.; Shu, L.; Si, C.J.; Zhang, X.Y.; Yu, X.L.; Gao, W. Dietary Patterns and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Meta-analysis. COPD 2016, 13, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodur, M.; Yilmaz, B.; Ağagündüz, D.; Ozogul, Y. Immunomodulatory Effects of Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Mechanistic Insights and Health Implications. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2025, 69, e202400752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Shi, K.; Cao, W.; Lv, J.; Guo, Y.; Pei, P.; Xia, Q.; Du, H.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; et al. Association between Fish Consumption and Risk of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease among Chinese Men and Women: An 11-Year Population-Based Cohort Study. J. Nutr. 2023, 152, 2771–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Lu, X.; Deng, J.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, D.; Qiu, F.; Yang, X.; Yang, R.; Fang, W.; Ran, P.; et al. Risk factors shared by COPD and lung cancer and mediation effect of COPD: Two center case-control studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2015, 26, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salari-Moghaddam, A.; Milajerdi, A.; Larijani, B.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Processed red meat intake and risk of COPD: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, R.P.; Hopkins, R.J. Is the “Western Diet” a New Smoking Gun for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease? Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2018, 15, 662–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Iersel, L.E.J.; Beijers, R.J.H.C.G.; Gosker, H.R.; Schols, A.M.W.J. Nutrition as a modifiable factor in the onset and progression of pulmonary function impairment in COPD: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 1434–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaluza, J.; Harris, H.; Linden, A.; Wolk, A. Long-term unprocessed and processed red meat consumption and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A prospective cohort study of women. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaluza, J.; Larsson, S.C.; Linden, A.; Wolk, A. Consumption of Unprocessed and Processed Red Meat and the Risk of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study of Men. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 184, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 25, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.; Johansson, I.; Blomberg, A.; Sundström, B. Adherence to a Mediterranean-like Diet as a Protective Factor Against COPD: A Nested Case-Control Study. COPD 2019, 16, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varraso, R.; Dumas, O.; Boggs, K.M.; Willett, W.C.; Speizer, F.E.; Camargo, C.A., Jr. Processed Meat Intake and Risk of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease among Middle-aged Women. eClinicalMedicine 2019, 14, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varraso, R.; Barr, R.G.; Willett, W.C.; Speizer, F.E.; Camargo, C.A., Jr. Fish intake and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 2 large US cohorts. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Batlle, J.; Mendez, M.; Romieu, I.; Balcells, E.; Benet, M.; Donaire-Gonzalez, D.; Ferrer, J.J.; Orozco-Levi, M.; Antó, J.M.; Garcia-Aymerich, J.; et al. Cured meat consumption increases risk of readmission in COPD patients. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 40, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varraso, R.; Willett, W.C.; Camargo, C.A., Jr. Prospective study of dietary fiber and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among US women and men. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 171, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, R.; Camargo, C.A., Jr.; Varraso, R.; Paik, D.C.; Willett, W.C.; Barr, R.G. Consumption of cured meats and prospective risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1002–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Paik, D.C.; Hankinson, J.L.; Barr, R.G. Cured meat consumption, lung function, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among United States adults. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 175, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varraso, R.; Jiang, R.; Barr, R.G.; Willett, W.C.; Camargo, C.A., Jr. Prospective study of cured meats consumption and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in men. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 166, 1438–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walda, I.C.; Tabak, C.; Smit, H.A.; Räsänen, L.; Fidanza, F.; Menotti, A.; Nissinen, A.; Feskens, E.J.; Kromhout, D. Diet and 20-year chronic obstructive pulmonary disease mortality in middle-aged men from three European countries. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 56, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabak, C.; Feskens, E.J.; Heederik, D.; Kromhout, D.; Menotti, A.; Blackburn, H.W. Fruit and fish consumption: A possible explanation for population differences in COPD mortality (The Seven Countries Study). Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 52, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahar, E.; Folsom, A.R.; Melnick, S.L.; Tockman, M.S.; Comstock, G.W.; Gennaro, V.; Higgins, M.W.; Sorlie, P.D.; Ko, W.J.; Szklo, M. Dietary n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and smoking-related chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study Investigators. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 331, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christenson, S.A.; Smith, B.M.; Bafadhel, M.; Putcha, N. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 2022, 399, 2227–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beijers, R.J.H.C.G.; Steiner, M.C.; Schols, A.M.W.J. The role of diet and nutrition in the management of COPD. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2023, 32, 230003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, T.; Jilma, B. Are leukotrienes really the world’s best bronchoconstrictors and at least 100 to 1000 times more potent than histamine? Drug Discov. Today 2025, 30, 104349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiserich, J.P.; Hristova, M.; Cross, C.E.; Jones, A.D.; Freeman, B.A.; Halliwell, B.; van der Vliet, A. Formation of nitric oxide-derived inflammatory oxidants by myeloperoxidase in neutrophils. Nature 1998, 391, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L. Arachidonic Acid 15-Lipoxygenase: Effects of Its Expression, Metabolites, and Genetic and Epigenetic Variations on Airway Inflammation. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2021, 13, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ülger, Z.; Hali, M.; Kalan, L.; Yavuz, B.B.; Cankurtaran, M.; Güngör, E.; Arioğul, S. Comprehensive assessment of malnutrition risk and related factors in a large group of community-dwelling older adults. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 29, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, J.; Flanagan, D.; McNaughton, S.A.; Nowson, C. Nutrition screening of older people in a community general practice, using the MNA-SF. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2013, 17, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirabbasi, E.; Najafiyan, M.; Cheraghi, M.; Shahar, S.; Abdul Manaf, Z.; Rajab, N.; Abdul Manap, R. Predictors’ factors of nutritional status of male chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. ISRN Nurs. 2012, 2012, 782626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Zaid, Z.; Shahar, S.; Jamal, A.R.; Mohd Yusof, N.A. Fish oil supplementation is beneficial on caloric intake, appetite and mid upper arm muscle circumference in children with leukaemia. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 21, 502–510. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, A.; Crivello, F.; Mazoyer, B.; Debette, S.; Tzourio, C.; Samieri, C. Fish Intake and MRI Burden of Cerebrovascular Disease in Older Adults. Neurology 2021, 97, e2213–e2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazelas, E.; Pierre, F.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Esseddik, Y.; Szabo de Edelenyi, F.; Agaesse, C.; De Sa, A.; Lutchia, R.; Gigandet, S.; Srour, B.; et al. Nitrites and nitrates from food additives and natural sources and cancer risk: Results from the NutriNet-Santé cohort. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 51, 1106–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.; Wang, L.; Yu, P.; Carrier, A.J.; Oakes, K.D.; Zhang, X. Exacerbated Protein Oxidation and Tyrosine Nitration through Nitrite-Enhanced Fenton Chemistry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakil, M.H.; Trisha, A.T.; Rahman, M.; Talukdar, S.; Kobun, R.; Huda, N.; Zzaman, W. Nitrites in Cured Meats, Health Risk Issues, Alternatives to Nitrites: A Review. Foods 2022, 11, 3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, D.C.; Dillon, J.; Galicia, E.; Tilson, M.D. The nitrite/collagen reaction: Non-enzymatic nitration as a model system for age-related damage. Connect. Tissue Res. 2001, 42, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, D.C.; Ramey, W.G.; Dillon, J.; Tilson, M.D. The nitrite/elastin reaction: Implications for in vivo degenerative effects. Connect. Tissue Res. 1997, 36, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, D.C.; Saito, L.Y.; Sugirtharaj, D.D.; Holmes, J.W. Nitrite-induced cross-linking alters remodeling and mechanical properties of collagenous engineered tissues. Connect. Tissue Res. 2006, 47, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciardolo, F.L.; Di Stefano, A.; Sabatini, F.; Folkerts, G. Reactive nitrogen species in the respiratory tract. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 533, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynaert, N.L.; Vanfleteren, L.E.G.W.; Perkins, T.N. The AGE-RAGE Axis and the Pathophysiology of Multimorbidity in COPD. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawada, A.; Machowiak, A.; Rychter, A.M.; Ratajczak, A.E.; Szymczak-Tomczak, A.; Dobrowolska, A.; Krela-Kaźmierczak, I. Accumulation of Advanced Glycation End-Products in the Body and Dietary Habits. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.I.; Ashfaq, F.; Alsayegh, A.A.; Hamouda, A.; Khatoon, F.; Altamimi, T.N.; Alhodieb, F.S.; Beg, M.M.A. Advanced glycation end product signaling and metabolic complications: Dietary approach. World J. Diabetes 2023, 14, 995–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Kaur, S.; Sarkar, M.; Sarin, B.C.; Changotra, H. The AGE-RAGE Axis and RAGE Genetics in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 60, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Studies | Category | Study Design | Location | Age Range | Sample Size | Gender | Adjustment Variables | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yu W., et al. [11] (2023) | Fish | cohort study | China | 30–79 | 252,238 | All | Body Mass Index (BMI), smoking status, education, fish oil intakes, marry, household income, physical activity, waist circumference, cooking and heating with solid fuel, meat, fresh vegetables and fruit intakes, area of residence, gender | 9 |

| Kaluza, J., et al. [16] (2019) | Processed and unprocessed meat | prospective cohort study | Sweden | 48–83 | 34,053 | Female | Age, education, BMI, total physical activity, smoking status and pack-years of smoking, alcohol consumption, intake of energy, and recommended food score and modified non-recommended food score | 9 |

| Fischer, A., et al. [20] (2019) | Fish and meat | Nested Case-Control Study | Northern Sweden | 30–61 | 370 | All | Sex, age, educational level, smoking states, BMI, living alone, total energy | 8 |

| Varraso, R., et al. [21] (2019) | Processed meat | cohort study | United States | 25–44 | 87,032 | Female | Age, smoking (never, former, current), pack -years of smoking, BMI, physical activity, total caloric intake, US region and race, modified AHEI-2010 | 8 |

| Kaluza, J. et al. [17] (2016) | Processed and unprocessed meat | prospective cohort study | Sweden | 45–79 | 43,848 | Male | Age, educational level, BMI, total physical activity, smoking status and pack-years of smoking, intake of energy, alcohol consumption, recommended food score and non-recommended food score | 7 |

| Yang, L. et al. [12] (2015) | Cured meat | case-control study | China | NA | 3188 | All | Pre-existing tuberculosis, smoking, passive smoking, occupational exposure to metallic toxicant, poor housing ventilation, biomass burning, cured meat consumption, and seldom vegetables/fruits consumption | 6 |

| Varraso, R., et al. [22] (2015) | Fish | cohort study | United States | 30–75 | 120,175 | All | Age, smoking status, pack-years of smoking, pack-years squared of smoking, secondhand tobacco exposure, race-ethnicity, physician visit, US region, spouse`s highest educational attainment, menopausal status, BMI, physical activity, multivitamin use, energy intake, and modified prudent and Western dietary patterns | 8 |

| de Batlle, J., et al. [23] (2012) | Cured Meat | cohort study | Spain | 60–76 | 274 | All | Age, FEV1, and total caloric intake | 7 |

| Varraso, R., et al. [24] (2010) | Cured Meat | prospective cohort study | United States | 40–75 | 111,580 | All | Age, sex, smoking, energy intake, BMI, US region, physician visits, physical activity, diabetes, and intakes of omega-3 and cured meat | 9 |

| Jiang, R., et al. [25] (2008) | Cured Meat | prospective cohort study | United States | 38–63 | 71,531 | Female | Age, smoking, and multiple other potential confounders | 9 |

| Jiang, R., et al. [26] (2007) | Cured Meat | Cross-sectional study | United States | ≥45 | 7352 | All | Age, smoking, and multiple other potential confounders | 6 |

| Varraso, R., et al. [27] (2007) | Cured Meat | prospective cohort study | United States | 40–75 | 42,915 | Male | Age, smoking status, pack-years, pack-years squared, energy intake, race/ethnicity, US region, BMI, and physical activity | 9 |

| Walda, I.C., et al. [28] (2002) | Fish | prospective cohort study | Europe | 50–69 | 2917 | Male | Country, age and smoking | 8 |

| Tabak, C., et al. [29] (1998) | Fish | Cohort study | United States, Italy, ex-Yugoslavia, The Netherlands, Finland, Japan, Greece | 50–69 | 12,763 | Male | Age, total energy intake, prevalence of cigarette smoking, work-related activity level and BMI | 7 |

| Shahar, E., et al. [30] (1994) | Fish | prospective cohort study | United States | 45–64 | 15,800 | All | Pack-years of smoking, age, sex, race, height, weight, energy intake, and educational level | 7 |

| Subgroup | No. of Study | OR (95%CI) | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Types of meat | |||

| Fish | 6 | 0.84 (0.72, 0.97) | 79.5% |

| Processed meat | 4 | 1.18 (1.02, 1.37) | 46.2% |

| Cured meat | 6 | 1.64 (1.41, 1.90) | 34.7% |

| Unprocessed meat | 2 | 0.93 (0.81, 1.07) | 31.2% |

| Region | |||

| America | 7 | 1.24 (0.87, 1.78) | 92.7% |

| Europe | 5 | 1.07 (0.92, 1.25) | 70.0% |

| Asia | 2 | 1.30 (0.87, 1.97) | 81.5% |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 4 | 1.10 (0.93, 1.30) | 73.9% |

| Female | 4 | 1.08 (0.90, 1.30) | 72.0% |

| All | 7 | 1.23 (0.91, 1.67) | 93.0% |

| Sample size | |||

| <1000 | 2 | 1.13 (0.77, 1.67) | 82.8% |

| >=1000 | 13 | 1.16 (1.01, 1.33) | 89.7% |

| Study design | |||

| Cohort study | 12 | 1.05 (0.94, 1.16) | 80.9% |

| Cross-sectional study | 1 | 1.78 (1.57, 2.02) | NA |

| Case-control study | 2 | 1.52 (1.10, 2.10) | 36.6% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Xia, H.; Hu, B.; Tian, P.; Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhou, Y.; Sui, J. Meat Consumption Associated with the Risk of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2026, 18, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010006

Chen Y, Xia H, Hu B, Tian P, Yang Y, Li M, Zhou Y, Sui J. Meat Consumption Associated with the Risk of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yutong, Hui Xia, Bihuan Hu, Peixuan Tian, Yu Yang, Mi Li, Yajie Zhou, and Jing Sui. 2026. "Meat Consumption Associated with the Risk of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010006

APA StyleChen, Y., Xia, H., Hu, B., Tian, P., Yang, Y., Li, M., Zhou, Y., & Sui, J. (2026). Meat Consumption Associated with the Risk of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 18(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010006