Eating Disorders and Autistic Traits Camouflaging: Insights from the EAT Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Assessment

2.2.1. Eating Disorder Inventory, Version 3 (EDI-3)

2.2.2. Ritvo Autism and Asperger Diagnostic Scale, Revised Version (RAADS-R)

2.2.3. Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ)

2.2.4. Empathy Quotient (EQ)

2.2.5. Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q)

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description and Clinical Features

3.2. Effects of ATs and Camouflaging

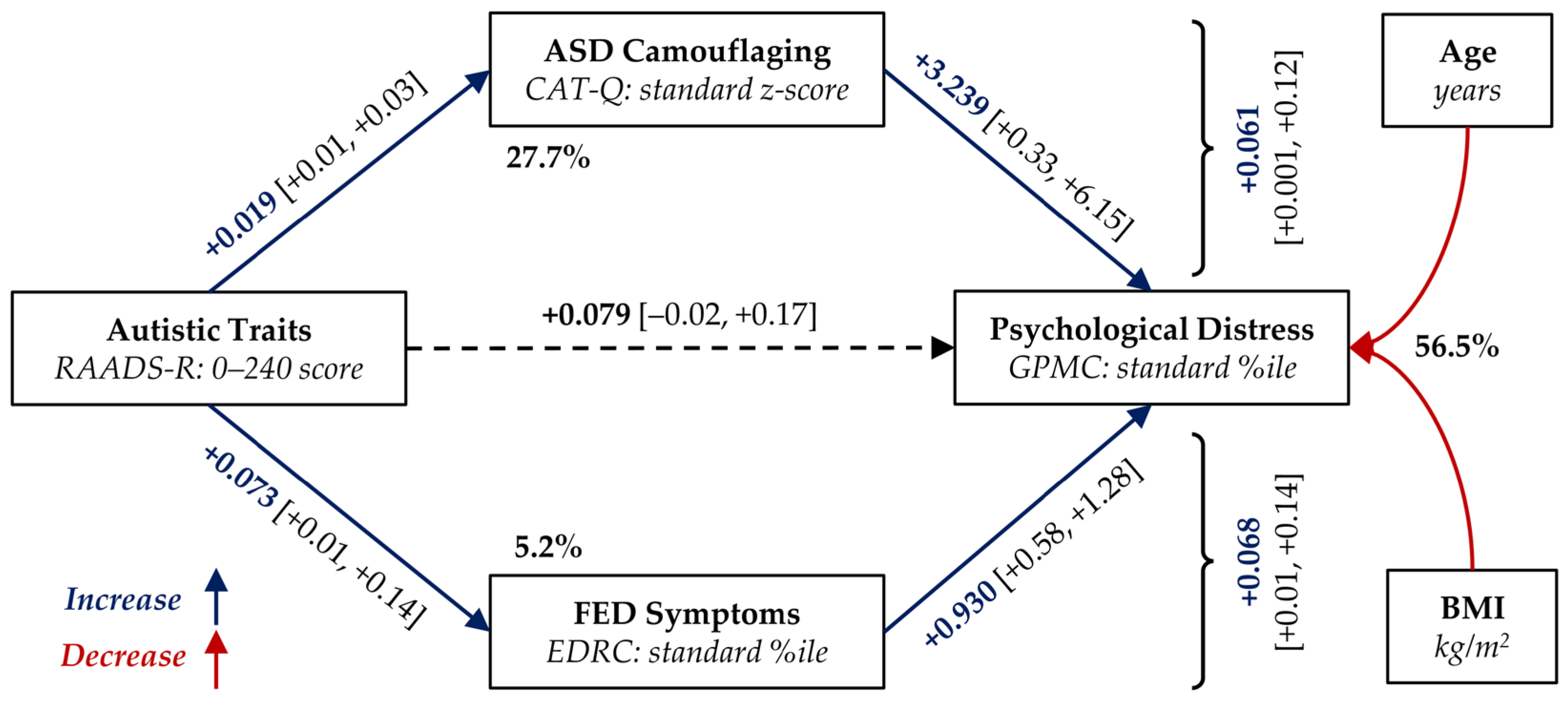

3.3. Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| %ile | Percentile |

| AN | Anorexia Nervosa |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| ATs | Autistic Traits |

| BED | Binge-Eating Disorder |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| BN | Bulimia Nervosa |

| -BP | Binge-Eating/Purging Sub-Type of AN |

| CAT-Q | Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire |

| CUDICA | Centro Unico per il trattamento dei DIsturbi del Comportamento Alimentare [Italian; One-stop centre for the treatment of FEDs of the Unit of Psychiatry and Eating Disorders] |

| DSM-5 | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition |

| EDI-3 | Eating Disorder Inventory, version 3 |

| EDRC | Eating Disorder Risk Composite scale (EDI-3) |

| FEDs | Feeding and Eating Disorders |

| GPMC | General Psychological Maladjustment Composite scale (EDI-3) |

| Max | Maximum Observed Value |

| min | Minimum Observed Value |

| N | Number of Observations |

| OSFED | Other Specified FED |

| Other | Diagnosis Group including OSFED and UFED |

| -R | Restrictive Sub-Type of AN |

| RAADS-R | Ritvo Autism Asperger Diagnostic Scale, Revised version |

| RDoC | Research Domain Criteria |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| UFED | Unspecified FED |

References

- American Psychiatric Association (Ed.) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5-TR, 5th ed.; text revision; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-0-89042-575-6. [Google Scholar]

- Treasure, J.; Duarte, T.A.; Schmidt, U. Eating Disorders. Lancet 2020, 395, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doll, H.A.; Petersen, S.E.; Stewart-Brown, S.L. Eating Disorders and Emotional and Physical Well-Being: Associations between Student Self-Reports of Eating Disorders and Quality of Life as Measured by the SF-36. Qual. Life Res. 2005, 14, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardi, V.; Tchanturia, K.; Treasure, J. Premorbid and Illness-Related Social Difficulties in Eating Disorders: An Overview of the Literature and Treatment Developments. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 1122–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attia, E.; Walsh, B.T. Eating Disorders: A Review. JAMA 2025, 333, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keski-Rahkonen, A.; Mustelin, L. Epidemiology of Eating Disorders in Europe: Prevalence, Incidence, Comorbidity, Course, Consequences, and Risk Factors. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2016, 29, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelli, L.; Draghetti, S.; Albert, U.; De Ronchi, D.; Atti, A.-R. Rates of Comorbid Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Eating Disorders: A Meta-Analysis of the Literature. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udo, T.; Grilo, C.M. Psychiatric and Medical Correlates of DSM-5 Eating Disorders in a Nationally Representative Sample of Adults in the United States. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 52, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boltri, M.; Sapuppo, W. Anorexia Nervosa and Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 306, 114271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickel, K.; Maier, S.; Endres, D.; Joos, A.; Maier, V.; Tebartz Van Elst, L.; Zeeck, A. Systematic Review: Overlap Between Eating, Autism Spectrum, and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagni, D.; Moscone, D.; Travaglione, S.; Cotugno, A. Using the Ritvo Autism Asperger Diagnostic Scale-Revised (RAADS-R) Disentangle the Heterogeneity of Autistic Traits in an Italian Eating Disorder Population. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2016, 32, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Lorenzi, P.; Carpita, B. Autistic Traits and Illness Trajectories. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health CP EMH 2019, 15, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundin, K.; Mahdi, S.; Isaksson, J.; Bölte, S. Functional Gender Differences in Autism: An International, Multidisciplinary Expert Survey Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health Model. Autism 2021, 25, 1020–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rynkiewicz, A.; Schuller, B.; Marchi, E.; Piana, S.; Camurri, A.; Lassalle, A.; Baron-Cohen, S. An Investigation of the ‘Female Camouflage Effect’ in Autism Using a Computerized ADOS-2 and a Test of Sex/Gender Differences. Mol. Autism 2016, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rynkiewicz, A.; Janas-Kozik, M.; Słopień, A. Girls and Women with Autism. Psychiatr. Pol. 2019, 53, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpita, B.; Nardi, B.; Pronestì, C.; Cerofolini, G.; Filidei, M.; Bonelli, C.; Massimetti, G.; Cremone, I.M.; Pini, S.; Dell’Osso, L. The Mediating Role of Social Camouflaging on the Relationship Between Autistic Traits and Orthorexic Symptoms. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passarini, S.; Guerrera, S.; Picilli, M.; Fucà, E.; Casula, L.; Menghini, D.; Pirchio, S.; Zanna, V.; Valeri, G.; Vicari, S. The Challenge of a Late Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder: Co-Occurring Trajectories and Camouflage Tendencies. a Case Report of a Young Autistic Female with Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 1447562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Califano, M.; Pruccoli, J.; Martucci, M.; Visconti, C.; Barasciutti, E.; Sogos, C.; Parmeggiani, A. Autism Spectrum Disorder Traits Predict Interoceptive Deficits and Eating Disorder Symptomatology in Children and Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa-A Cross-Sectional Analysis: Italian Preliminary Data. Pediatr. Rep. 2024, 16, 1077–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, S.; Moore, F.; Duffy, F.; Clark, L.; Suratwala, T.; Knightsmith, P.; Gillespie-Smith, K. Camouflaging, Not Sensory Processing or Autistic Identity, Predicts Eating Disorder Symptoms in Autistic Adults. Autism 2024, 28, 2858–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpita, B.; Nardi, B.; Pini, S.; Parri, F.; Perrone, P.; Pronestì, C.; Giovannoni, F.; Russomanno, G.; Bonelli, C.; Massimetti, G.; et al. Social Camouflaging of Autistic Traits Is Associated with More Severe Symptoms among Subjects with Feeding and Eating Disorders. Eat. Weight Disord.-Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2025, 30, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, L.; Rosenvinge, J.H.; Friborg, O.; Rokkedal, K. Validating the Eating Disorder Inventory-3 (EDI-3): A Comparison Between 561 Female Eating Disorders Patients and 878 Females from the General Population. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2011, 33, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D.M. Eating Disorder Inventory-3 (EDI-3) Professional Manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2004, 35, 478–479. [Google Scholar]

- Garner, D.M.; Conti, C.; Giannini, M. EDI-3 RF: Eating Disorder Inventory-3 Referral Form: Manuale; Giunti O.S. Organizzazioni Speciali: Firenze, Italy, 2008; ISBN 978-88-09-06316-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ritvo, R.A.; Ritvo, E.R.; Guthrie, D.; Ritvo, M.J.; Hufnagel, D.H.; McMahon, W.; Tonge, B.; Mataix-Cols, D.; Jassi, A.; Attwood, T.; et al. The Ritvo Autism Asperger Diagnostic Scale-Revised (RAADS-R): A Scale to Assist the Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Adults: An International Validation Study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2011, 41, 1076–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brugha, T.; Tyrer, F.; Leaver, A.; Lewis, S.; Seaton, S.; Morgan, Z.; Tromans, S.; Van Rensburg, K. Testing Adults by Questionnaire for Social and Communication Disorders, Including Autism Spectrum Disorders, in an Adult Mental Health Service Population. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 29, e1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscone, D.; Vagni, D. Guida Completa alla Sindrome di Asperger; Attwood, T., Ed.; Edra: Milano, Italy, 2019; ISBN 978-88-214-4884-3. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Wheelwright, S.; Skinner, R.; Martin, J.; Clubley, E. The Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger Syndrome/High-Functioning Autism, Malesand Females, Scientists and Mathematicians. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2001, 31, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruta, L.; Mazzone, D.; Mazzone, L.; Wheelwright, S.; Baron-Cohen, S. The Autism-Spectrum Quotient—Italian Version: A Cross-Cultural Confirmation of the Broader Autism Phenotype. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 42, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Wheelwright, S. The Empathy Quotient: An Investigation of Adults with Asperger Syndrome or High Functioning Autism, and Normal Sex Differences. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2004, 34, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preti, A.; Vellante, M.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Zucca, G.; Petretto, D.R.; Masala, C. The Empathy Quotient: A Cross-Cultural Comparison of the Italian Version. Cognit. Neuropsychiatry 2011, 16, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, L.; Mandy, W.; Lai, M.-C.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Allison, C.; Smith, P.; Petrides, K.V. Development and Validation of the Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q). J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 819–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, L.; Petrides, K.V.; Allison, C.; Smith, P.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Lai, M.-C.; Mandy, W. “Putting on My Best Normal”: Social Camouflaging in Adults with Autism Spectrum Conditions. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 2519–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Cremone, I.M.; Muti, D.; Massimetti, G.; Lorenzi, P.; Carmassi, C.; Carpita, B. Validation of the Italian Version of the Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q) in a University Population. Compr. Psychiatry 2022, 114, 152295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Little, T.D. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; Methodology in the Social Sciences; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1-4625-4903-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F.; Allison, P.D.; Alexander, S.M. Errors-in-Variables Regression as a Viable Approach to Mediation Analysis with Random Error-Tainted Measurements: Estimation, Effectiveness, and an Easy-to-Use Implementation. Behav. Res. Methods 2025, 57, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, Reference Index, Version 4.4.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024.

- Hayes, A.F. PROCESS Macro (Version 5.0). Available online: https://processmacro.org/index.html (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Westwood, H.; Tchanturia, K. Autism Spectrum Disorder in Anorexia Nervosa: An Updated Literature Review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiansen, G.B.; Petersen, L.V.; Chatwin, H.; Yilmaz, Z.; Schendel, D.; Bulik, C.M.; Grove, J.; Brikell, I.; Semark, B.D.; Holde, K.; et al. The Role of Co-Occurring Conditions and Genetics in the Associations of Eating Disorders with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2025, 30, 2127–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insel, T.; Cuthbert, B.; Garvey, M.; Heinssen, R.; Pine, D.S.; Quinn, K.; Sanislow, C.; Wang, P. Research Domain Criteria (RDoC): Toward a New Classification Framework for Research on Mental Disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 2010, 167, 748–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirník, Z.; Szadvári, I.; Borbélyová, V.; Tomova, A. Altered Sex Differences Related to Food Intake, Hedonic Preference, and FosB/deltaFosB Expression within Central Neural Circuit Involved in Homeostatic and Hedonic Food Intake Regulation in Shank3B Mouse Model of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neurochem. Int. 2024, 181, 105895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Lorenzi, P.; Carpita, B. Camouflaging: Psychopathological Meanings and Clinical Relevance in Autism Spectrum Conditions. CNS Spectr. 2021, 26, 437–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patients (N = 131) | N (%) or Mean ± SD [Min, Max] | Diagnosis | RAARDS-R | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FED diagnosis | AN-R: | 20 (15.3%) | - | |

| AN-BP: | 13 (9.9%) | |||

| BN: | 24 (18.3%) | |||

| BED: | 38 (29.0%) | |||

| OSFED: | 29 (22.1%) | |||

| UFED: | 7 (5.3%) | |||

| Sex | Females: | 117 (89.3%) | ||

| Age at assessment | [years] | 32.8 ± 14.51 [17, 64] | * | |

| Schooling (6) | Middle school: | 30 (24.0%) | ||

| High school: | 63 (50.4%) | |||

| Degree or more: | 32 (25.6%) | |||

| School failures (62) | Any: | 24 (34.8%) | ↑ | |

| Relationship | Single: | 88 (67.2%) | ||

| Couple: | 43 (32.8%) | |||

| Housing (1) | Old-family: | 67 (51.5%) | (*) | |

| New-family: | 34 (26.2%) | |||

| Alone: | 24 (18.5%) | |||

| Other: | 5 (3.9%) | |||

| Current occupation (1) | Employed: | 75 (57.8%) | (*) | |

| Student: | 41 (31.5%) | |||

| House-working: | 3 (2.3%) | |||

| Unemployed: | 8 (6.2%) | |||

| Retired: | 3 (2.3%) | |||

| Age at FED onset (8) | [years] | 17.9 ± 9.15 [5, 53] | ||

| Duration of FED (8) | [years] | 14.2 ± 14.08 [0, 57] | (*) | |

| BMI | [kg/m2] | 25.9 ± 9.13 [13.2, 53.7] | * | |

| Previous hospitalizations (1) | Any (for FED): | 13 (10.0%) | * | |

| Psychiatric comorbidity | Any (non-FED): | 48 (36.6%) | ↑ | |

| Previous support (1) | Any (mental health): | 92 (70.8%) | ||

| Non-psychiatric comorbidity | Any: | 66 (50.4%) | ||

| Chronic: | 62 (50.4%) | |||

| Severe: | 12 (11.3%) | (*) | ↑ | |

| Antidepressant (2,4) | Previous: | 30 (23.3%) | ↑ | |

| Current: | 45 (35.4%) | |||

| Stabilizer (2,4) | Previous: | 8 (6.2%) | ||

| Current: | 11 (8.7%) | |||

| Antipsychotics (2,4) | Previous: | 10 (7.8%) | ↑ | |

| Current: | 17 (13.4%) | |||

| Benzodiazepines (2,4) | Previous: | 19 (14.7%) | ||

| Current: | 24 (18.9%) | |||

| Other drugs (2,4) | Previous: | 23 (17.8%) | ||

| Current: | 32 (25.2%) | |||

| EDI-3 scales | ||||

| Eating Disorder Risk Composite | [standard %ile] | 85.9 ± 12.43 [39, 99] | * | ↑ |

| Global Psychological Maladjustment | [standard %ile] | 67.0 ± 21.56 [1, 99] | * | ↑ |

| RAADS-R (with sub-scales) | ||||

| Possible ASD (above cut-off) | Original version (≥65): | 70 (53.4%) | - | |

| Clinical setting (≥120): | 21 (16.0%) | - | ||

| Total score | [score: 0, 240] | 74.0 ± 39.36 [7, 168] | - | |

| Social relatedness scale | [score: 0, 117] | 36.4 ± 20.92 [3, 98] | - | |

| Circumscribed interests scale | [score: 0, 42] | 16.3 ± 8.67 [0, 41] | - | |

| Language scale | [score: 0, 21] | 4.8 ± 4.19 [0, 15] | - | |

| Sensory–Motor scale | [score: 0, 60] | 16.5 ± 11.92 [0, 50] | - | |

| CAT-Q (with sub-scales) | ||||

| Camouflage (above cut-off) | High score (≥100): | 33 (25.19%) | ↑ | |

| Total score | [standard z] | +0.1 ± 1.44 [−2.7, +3.2] | ↑ | |

| Compensation score | [standard z] | −0.3 ± 1.19 [−1.8, +3.2] | ↑ | |

| Masking score | [standard z] | <+0.1 ± 1.37 [−2.8, +2.9] | ↑ | |

| Assimilation score | [standard z] | +0.4 ± 1.38 [−2.2, +3.6] | ↑ | |

| Other ASD-related | ||||

| Adult Autism Spectrum Quotient (13) | [score: 0, 50] | 20.5 ± 7.78 [6, 42] | ↑ | |

| Empathy Quotient (3) | [score: 0, 80] | 44.9 ± 11.89 [9, 70] | ↑ | |

| RAADS-R | CAT-Q | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | t16.1 = −0.65 | t17.4 = 0.71 |

| Age at assessment | r = +0.040 [−0.133, +0.210] | r = −0.172 [−0.334, −0.001] * |

| BMI | r = −0.127 [−0.292, +0.046] | r = −0.163 [−0.326, +0.009] |

| EDI-3-specific scales | ||

| Eating Disorder Risk Composite | r = +0.205 [+0.035, +0.364] * | r = +0.153 [−0.019, +0.316] |

| Drive for Thinness | r = +0.123 [−0.050, +0.288] | r = +0.168 [−0.004, +0.330] |

| Bulimia | r = +0.144 [−0.028, +0.308] | r = +0.039 [−0.134, +0.209] |

| Body Dissatisfaction | r = +0.202 [+0.031, +0.361] * | r = +0.092 [−0.081, +0.259] |

| EDI-3 psychological scales | ||

| Global Psychological Maladjustment | r = +0.373 [+0.215, +0.512] * | r = +0.426 [+0.274, +0.557] * |

| Ineffectiveness Composite | r = +0.355 [+0.195, +0.496] * | r = +0.371 [+0.213, +0.510] * |

| Interpersonal Problems Composite | r = +0.429 [+0.278, +0.560] * | r = +0.364 [+0.205, +0.504] * |

| Affective Problems Composite | r = +0.316 [+0.153, +0.463] * | r = +0.353 [+0.193, +0.495] * |

| Overcontrol Composite | r = +0.287 [+0.122, +0.437] * | r = +0.439 [+0.290, +0.568] * |

| Low Self-Esteem | r = +0.298 [+0.134, +0.447] * | r = +0.318 [+0.155, +0.464] * |

| Personal Alienation | r = +0.359 [+0.200, +0.500] * | r = +0.385 [+0.229, +0.522] * |

| Interpersonal Insecurity | r = +0.411 [+0.257, +0.544] * | r = +0.312 [+0.149, +0.459] * |

| Interpersonal Alienation | r = +0.318 [+0.155, +0.465] * | r = +0.323 [+0.161, +0.469] * |

| Interoceptive Deficits | r = +0.288 [+0.122, +0.438] * | r = +0.300 [+0.135, +0.448] * |

| Emotional Dysregulation | r = +0.289 [+0.124, +0.439] * | r = +0.359 [+0.199, +0.499] * |

| Perfectionism | r = +0.234 [+0.066, +0.390] * | r = +0.300 [+0.136, +0.449] * |

| Ascetism | r = +0.261 [+0.093, +0.414] * | r = +0.435 [+0.285, +0.565] * |

| Maturity Fears | r = +0.204 [+0.034, +0.363] * | r = +0.205 [+0.035, +0.364] * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cesco, M.; Garzitto, M.; Croccia, V.; Bier, F.; Saetti, L.; Balestrieri, M.; Colizzi, M. Eating Disorders and Autistic Traits Camouflaging: Insights from the EAT Study. Nutrients 2026, 18, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010034

Cesco M, Garzitto M, Croccia V, Bier F, Saetti L, Balestrieri M, Colizzi M. Eating Disorders and Autistic Traits Camouflaging: Insights from the EAT Study. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010034

Chicago/Turabian StyleCesco, Maddalena, Marco Garzitto, Veronica Croccia, Francesca Bier, Luana Saetti, Matteo Balestrieri, and Marco Colizzi. 2026. "Eating Disorders and Autistic Traits Camouflaging: Insights from the EAT Study" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010034

APA StyleCesco, M., Garzitto, M., Croccia, V., Bier, F., Saetti, L., Balestrieri, M., & Colizzi, M. (2026). Eating Disorders and Autistic Traits Camouflaging: Insights from the EAT Study. Nutrients, 18(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010034