Polyphenol-Enriched Extracts from Leaves of Mediterranean Plants as Natural Inhibitors of Monoamine Oxidase (MAO)-A and MAO-B Enzymes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Polyphenol-Enriched Extracts from Leaves of Mediterranean Plants

2.3. HPLC Analysis of Extracts from Leaves of Mediterranean Plants

2.4. Monoamine Oxidase Assay

2.5. Cell Cultures and Treatments

2.6. Total Cell Protein Lysates for Western Blotting Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

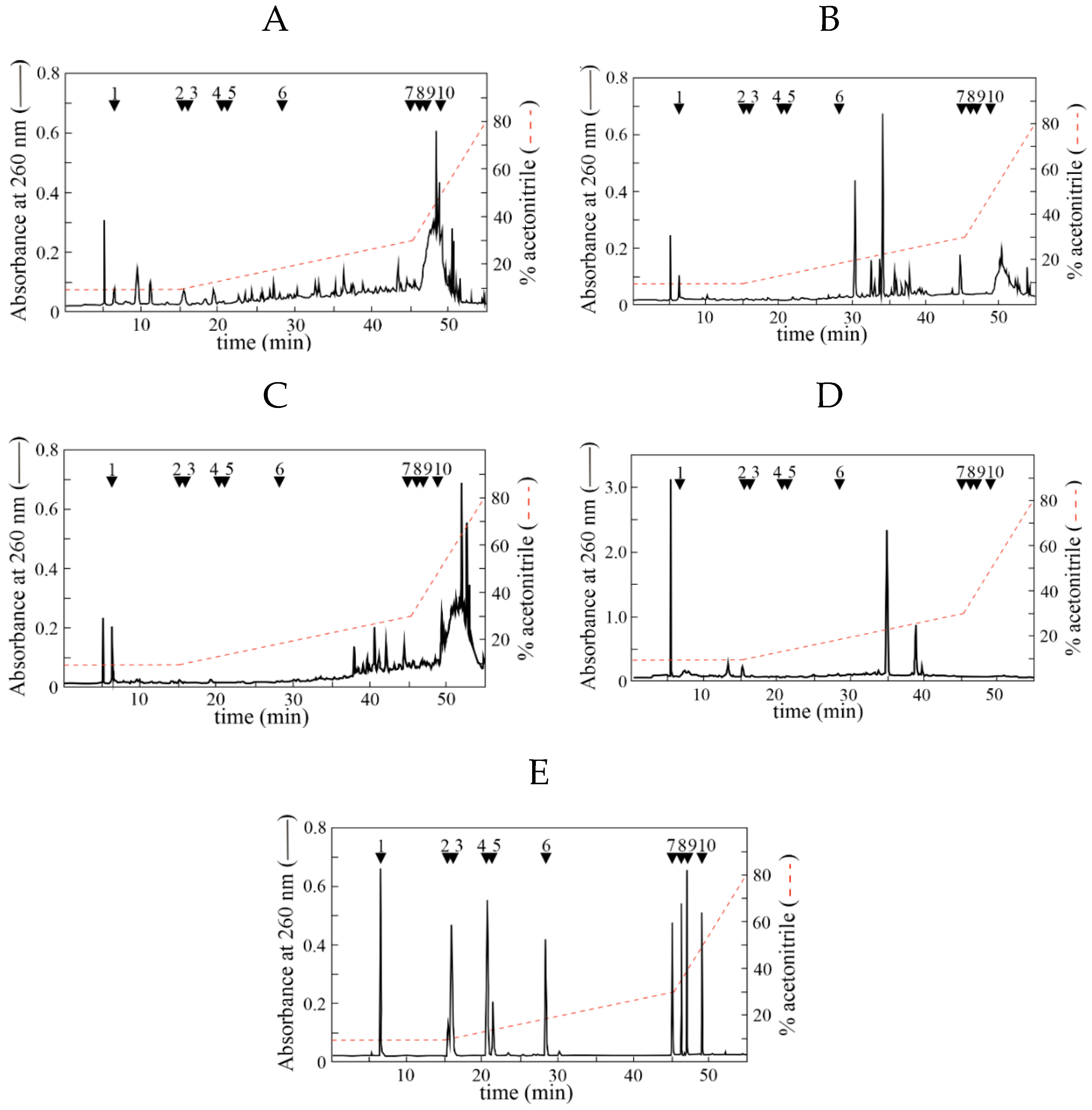

3.1. Identification of Organic Compounds Extracted from Leaves of Mediterranean Plants

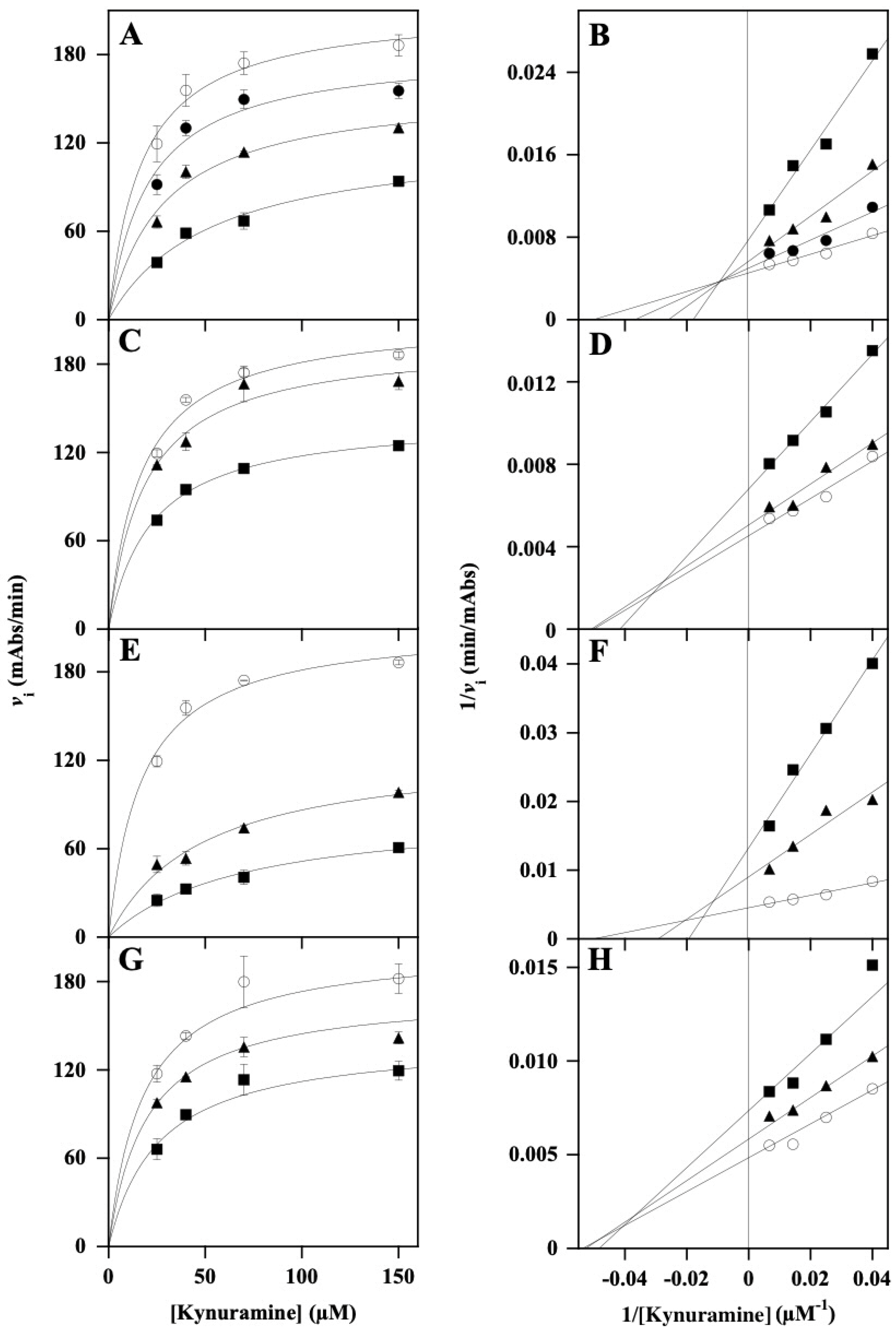

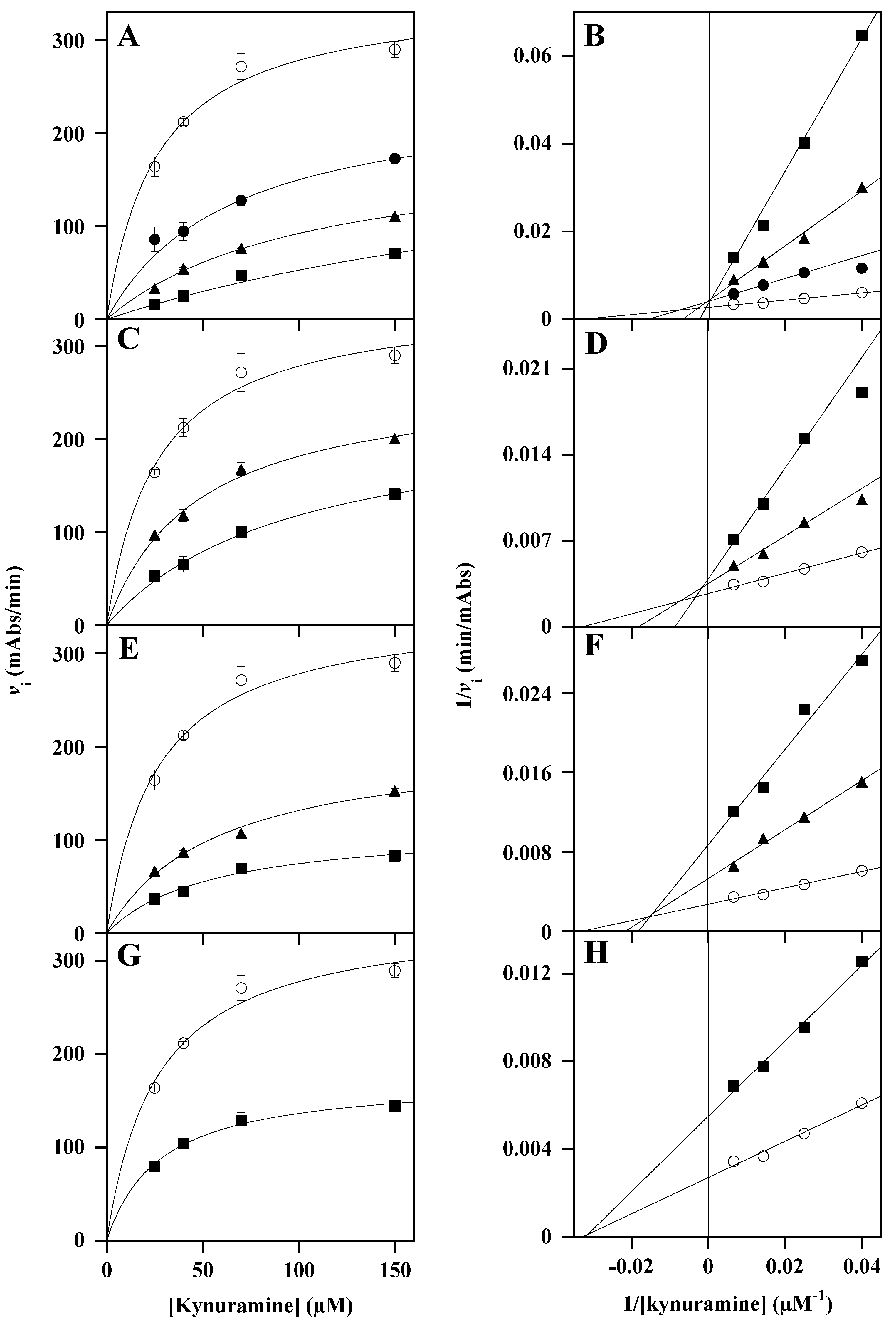

3.2. Effect of Polyphenol-Enriched Plant Extracts on Functionality of Monoamine Oxidases

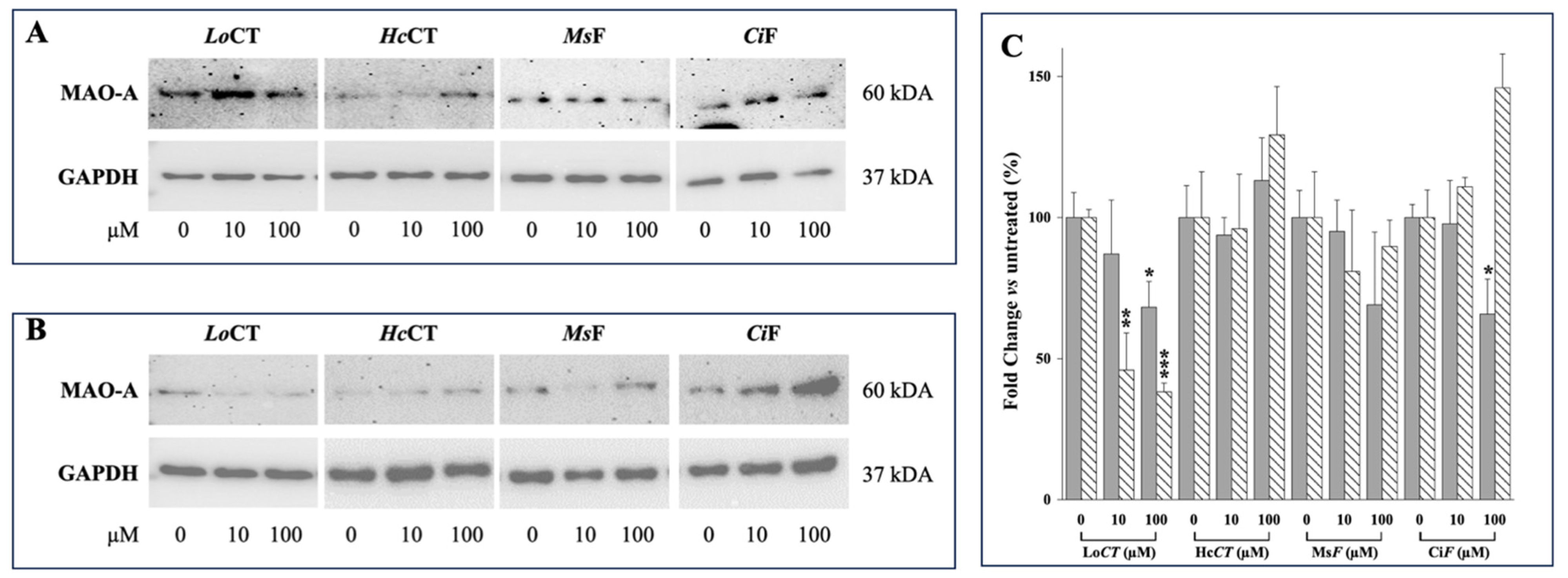

3.3. Effect of Polyphenol-Enriched Plant Extracts on MAO-A and MAO-B Protein Expression Level in the Human Gastric Adenocarcinoma AGS and Neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y Cells

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feigin, V.L.; Vos, T.; Nichols, E.; Owolabi, M.O.; Carroll, W.M.; Dichgans, M.; Deuschl, G.; Parmar, P.; Brainin, M.; Murray, C. The global burden of neurological disorders: Translating evidence into policy. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, D.V.C.; Esteves, F.; Rajado, A.T.; Silva, N.; Araújo, I.; Bragança, J.; Castelo-Branco, P.; Nóbrega, C. Assessing cognitive decline in the aging brain: Lessons from rodent and human studies. npj Aging 2023, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.J. Parkinson’s disease: Health-related quality of life, economic cost, and implications of early treatment. Am. J. Manag. Care 2010, 16, S87–S93. [Google Scholar]

- Azam, S.; Haque, M.E.; Balakrishnan, R.; Kim, I.S.; Choi, D.K. The Ageing Brain: Molecular and Cellular Basis of Neurodegeneration. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 683459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Campo, M.; Peeters, C.F.W.; Johnson, E.C.B.; Vermunt, L.; Hok, A.H.Y.S.; van Nee, M.; Chen-Plotkin, A.; Irwin, D.J.; Hu, W.T.; Lah, J.J.; et al. CSF proteome profiling across the Alzheimer’s disease spectrum reflects the multifactorial nature of the disease and identifies specific biomarker panels. Nat. Aging 2022, 2, 1040–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gątarek, P.; Kałużna-Czaplińska, J. Integrated metabolomics and proteomics analysis of plasma lipid metabolism in Parkinson’s disease. Expert Rev. Proteom. 2024, 21, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caligiore, D.; Giocondo, F.; Silvetti, M. The Neurodegenerative Elderly Syndrome (NES) hypothesis: Alzheimer and Parkinson are two faces of the same disease. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2022, 13, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binda, C.; Mattevi, A.; Edmondson, D.E. Structural properties of human monoamine oxidases A and B. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2011, 100, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youdim, M.B.; Edmondson, D.; Tipton, K.F. The therapeutic potential of monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geha, R.M.; Rebrin, I.; Chen, K.; Shih, J.C. Substrate and inhibitor specificities for human monoamine oxidase A and B are influenced by a single amino acid. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 9877–9882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimbiscus, M.; Kostenko, O.; Malone, D. MAO inhibitors: Risks, benefits, and lore. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2010, 77, 859–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehuman, N.A.; Mathew, B.; Jat, R.K.; Nicolotti, O.; Kim, H. A Comprehensive Review of Monoamine Oxidase-A Inhibitors in their Syntheses and Potencies. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2020, 23, 898–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhawna; Kumar, A.; Bhatia, M.; Kapoor, A.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, S. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors: A concise review with special emphasis on structure activity relationship studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 242, 114655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.U.; Kim, S.; Sim, J.; Yang, S.; An, H.; Nam, M.H.; Jang, D.P.; Lee, C.J. Redefining differential roles of MAO-A in dopamine degradation and MAO-B in tonic GABA synthesis. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 1148–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Rangra, N.K. Recent Advancements and SAR Studies of Synthetic Coumarins as MAO-B Inhibitors: An Updated Review. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2024, 24, 1834–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carradori, S.; Secci, D.; Petzer, J.P. MAO inhibitors and their wider applications: A patent review. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2018, 28, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bulck, M.; Sierra-Magro, A.; Alarcon-Gil, J.; Perez-Castillo, A.; Morales-Garcia, J.A. Novel Approaches for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Tiwari, A.; Sharma, A. Changing Paradigm from one Target one Ligand Towards Multi-target Directed Ligand Design for Key Drug Targets of Alzheimer Disease: An Important Role of In Silico Methods in Multi-target Directed Ligands Design. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 726–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Esparza Mdel, R.; Torres-Ramos, M.A. Neuroprotection by natural polyphenols: Molecular mechanisms. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Agents Med. Chem. 2010, 10, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasso, R.; Pagliara, V.; D’Angelo, S.; Rullo, R.; Masullo, M.; Arcone, R. Annurca Apple Polyphenol Extract Affects Acetyl- Cholinesterase and Mono-Amine Oxidase In Vitro Enzyme Activity. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Errico, A.; Reveglia, P.; Nasso, R.; Maugeri, A.; Masullo, M.; Arcone, R.; Corso, G.; De Vendittis, E.; Rullo, R. Effects of Polyphenolic Extracts from Mediterranean Forage Crops on Cholinesterases and Amyloid Aggregation Relevant to Neurodegenerative Diseases. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2026; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, R.F.M.; Pogačnik, L. Polyphenols from Food and Natural Products: Neuroprotection and Safety. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcone, R.; D’Errico, A.; Nasso, R.; Rullo, R.; Poli, A.; Di Donato, P.; Masullo, M. Inhibition of Enzymes Involved in Neurodegenerative Disorders and Aβ1–40 Aggregation by Citrus limon Peel Polyphenol Extract. Molecules 2023, 28, 6332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias-Sánchez, R.A.; Torner, L.; Fenton Navarro, B. Polyphenols and Neurodegenerative Diseases: Potential Effects and Mechanisms of Neuroprotection. Molecules 2023, 28, 5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tava, A.; Biazzi, E.; Ronga, D.; Pecetti, L.; Avato, P. Biologically active compounds from forage plants. Phytochem. Rev. 2022, 21, 471–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosme, F.; Aires, A.; Pinto, T.; Oliveira, I.; Vilela, A.; Gonçalves, B. A Comprehensive Review of Bioactive Tannins in Foods and Beverages: Functional Properties, Health Benefits, and Sensory Qualities. Molecules 2025, 30, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bora, K.S.; Sharma, A. Evaluation of Antioxidant and Cerebroprotective Effect of Medicago sativa Linn. against Ischemia and Reperfusion Insult. Evid. Based Complement Alternat. Med. 2011, 2011, 792167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlando, B.; Pastorino, G.; Salis, A.; Damonte, G.; Clericuzio, M.; Cornara, L. The bioactivity of Hedysarum coronarium extracts on skin enzymes and cells correlates with phenolic content. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 1984–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perović, J.; Tumbas Šaponjac, V.; Kojić, J.; Krulj, J.; Moreno, D.A.; García-Viguera, C.; Bodroža-Solarov, M.; Ilić, N. Chicory (Cichorium intybus L.) as a food ingredient—Nutritional composition, bioactivity, safety, and health claims: A review. Food Chem. 2021, 336, 127676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Khan, W.R.; Yousaf, N.; Akram, S.; Murtaza, G.; Kudus, K.A.; Ditta, A.; Rosli, Z.; Rajpar, M.N.; Nazre, M. Exploring the Phytochemicals and Anti-Cancer Potential of the Members of Fabaceae Family: A Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rullo, R.; Nasso, R.; D’Errico, A.; Biazzi, E.; Tava, A.; Landi, N.; Di Maro, A.; Masullo, M.; De Vendittis, E.; Arcone, R. Effect of polyphenolic extracts from leaves of Mediterranean forage crops on enzymes involved in the oxidative stress, and useful for alternative cancer treatments. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 15, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Guo, L.; Sun, Z.; Yang, G.; Guo, J.; Chen, K.; Xiao, R.; Yang, X.; Sheng, L. Monoamine Oxidase A is a Major Mediator of Mitochondrial Homeostasis and Glycolysis in Gastric Cancer Progression. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 8023–8035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pifferi, A.; Chiaino, E.; Fernandez-Abascal, J.; Bannon, A.C.; Davey, G.P.; Frosini, M.; Valoti, M. Exploring the Regulation of Cytochrome P450 in SH-SY5Y Cells: Implications for the Onset of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidemberg, D.M.; Ferreira, M.A.; Takahashi, T.N.; Gomes, P.C.; Cesar-Tognoli, L.M.; da Silva-Filho, L.C.; Tormena, C.F.; da Silva, G.V.; Palma, M.S. Monoamine oxidase inhibitory activities of indolylalkaloid toxins from the venom of the colonial spider Parawixia bistriata: Functional characterization of PwTX-I. Toxicon 2009, 54, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, I.E.; Osman, E.E.; Saeed, A.; Ming, L.C.; Goh, K.W.; Razi, P.; Abdullah, A.D.I.; Dahab, M. Plant extracts as emerging modulators of neuroinflammation and immune receptors in Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, H.; Siddique, Y.H. Effect of Natural Plant Products on Alzheimer’s Disease. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2024, 23, 246–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.M.; Gabr, M.T. Multitarget therapeutic strategies for Alzheimer’s disease. Neural. Regen. Res. 2019, 14, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoulaki, E.E.; Dimopoulos, D.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D. Multitarget Compounds Designed for Alzheimer, Parkinson, and Huntington Neurodegeneration Diseases. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajchman, M.; Montero, L.; Valdés, A.; Herrero, M. Recent advances in dietary phytochemicals against Alzheimer’s disease: Extraction and multitarget evaluation of their effects. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2025, 63, 101312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.M.; Jang, H.J.; Kang, M.G.; Song, S.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Noh, J.I.; Park, J.E.; Park, D.; Yee, S.T.; et al. Acetylcholinesterase and monoamine oxidase-B inhibitory activities by ellagic acid derivatives isolated from Castanopsis cuspidata var. sieboldii. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, M.; Motti, M.L.; Meccariello, R.; Mazzeo, F. Resveratrol and Physical Activity: A Successful Combination for the Maintenance of Health and Wellbeing? Nutrients 2025, 17, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motti, M.L.; Tafuri, D.; Donini, L.; Masucci, M.T.; De Falco, V.; Mazzeo, F. The Role of Nutrients in Prevention, Treatment and Post-Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19). Nutrients 2022, 14, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaurasiya, N.D.; Leon, F.; Muhammad, I.; Tekwani, B.L. Natural Products Inhibitors of Monoamine Oxidases-Potential New Drug Leads for Neuroprotection, Neurological Disorders, and Neuroblastoma. Molecules 2022, 27, 4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.H.; Ko, M.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Ham, J.E.; Choi, J.Y.; Hwang, K.W.; Park, S.Y. Neuroprotective Effects of Davallia mariesii Roots and Its Active Constituents on Scopolamine-Induced Memory Impairment in In Vivo and In Vitro Studies. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondeva-Burdina, M.; Mateev, E.; Angelov, B.; Tzankova, V.; Georgieva, M. In Silico Evaluation and In Vitro Determination of Neuroprotective and MAO-B Inhibitory Effects of Pyrrole-Based Hydrazones: A Therapeutic Approach to Parkinson’s Disease. Molecules 2022, 27, 8485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youdim, K.A.; Dobbie, M.S.; Kuhnle, G.; Proteggente, A.R.; Abbott, N.J.; Rice-Evans, C. Interaction between flavonoids and the blood-brain barrier: In Vitro studies. J. Neurochem. 2003, 85, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, D.O. Polyphenols and the human brain: Plant “secondary metabolite” ecologic roles and endogenous signaling functions drive benefits. Adv. Nutr. 2014, 5, 515–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, G.; Clifford, M.N. Role of the small intestine, colon and microbiota in determining the metabolic fate of polyphenols. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 139, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, K.; Yoshioka, Y.; Terao, J. Role of Intestinal Microbiota in the Bioavailability and Physiological Functions of Dietary Polyphenols. Molecules 2019, 24, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Extract | MAO-A | MAO-B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration Interval (µM) | IC50 (µM) | Concentration Interval (µM) | IC50 (µM) | |

| LoCT | 0–50 | 39 ± 8 | 0–50 | 24 ± 5 |

| HcCT | 0–50 | 51 ± 5 | 0–50 | 31 ± 4 |

| MsF | 0–50 | 34 ± 6 | 0–50 | 30 ± 3 |

| CiF | 0–50 | 80 ± 18 | 0–50 | 83 ± 19 |

| Extract | Concentration (µM) | KM kynuramine (µM) * | Vmax (mAbs/min) * | Putative Inhibition Mechanism | Ki (µM) | Calculation of Ki (From Vmax) | Ki (µM) | Calculation of Ki (From KM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 18.9 ± 2.1 | 215 ± 7 | ||||||

| LoCT | 10 | 23.7 ± 3.5 | 192 ± 8 | mixed | 31.7 ± 2.5 | Equation (1) | 78.9 ± 4.1 | Equation (2) |

| 25 | 33.5 ± 5.1 | 167 ± 9 | ||||||

| 50 | 54.3 ± 1.5 | 127 ± 5 | ||||||

| HcCT | 25 | 19.2 ± 0.5 | 197 ± 1 | non-competitive | 103 ± 2 | Equation (2) | ||

| 50 | 23.2 ± 0.9 | 145 ± 2 | ||||||

| MsF | 25 | 41.1 ± 7.0 | 119 ± 9 | mixed | 23.6 ± 2.4 | Equation (1) | 30.9 ± 1.5 | Equation (2) |

| 50 | 60.2 ± 8.7 | 81 ± 6 | ||||||

| CiF | 25 | 19.2 ± 0.2 | 172 ± 1 | non-competitive | 104 ± 5 | Equation (2) | ||

| 50 | 23.2 ± 2.6 | 138 ± 3 |

| Extract | Concentration (µM) | KM kynuramine (µM) * | Vmax (mAbs/min) * | Putative Inhibition Mechanism | Ki (µM) | Calculation of Ki (From Vmax) | Ki (µM) | Calculation of Ki (From KM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 28.0 ± 1.7 | 361 ± 24 | ||||||

| LoCT | 10 | 64.5 ± 0.4 | 246 ± 1 | competitive | 6.4 ± 0.5 | Equation (2) | ||

| 25 | 127 ± 22 | 214 ± 24 | ||||||

| 50 | 380 ± 51 | 256 ± 29 | ||||||

| HcCT | 25 | 50.6 ± 4.4 | 275 ± 9 | competitive | 24.9 ± 2.3 | Equation (2) | ||

| 50 | 107 ± 9 | 245 ± 11 | ||||||

| MsF | 25 | 51.6 ± 5.2 | 197 ± 9 | mixed | 42.4.0 ± 4.3 | Equation (1) | 27.2 ± 1.4 | Equation (2) |

| 50 | 54.9 ± 0.1 | 115 ± 1 | ||||||

| CiF | 50 | 29.4 ± 1.8 | 178 ± 4 | non-competitive | 48.9 ± 0.6 | Equation (1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

D’Errico, A.; Nasso, R.; Ruggiero, M.; Rullo, R.; De Vendittis, E.; Masullo, M.; Mazzeo, F.; Arcone, R. Polyphenol-Enriched Extracts from Leaves of Mediterranean Plants as Natural Inhibitors of Monoamine Oxidase (MAO)-A and MAO-B Enzymes. Nutrients 2026, 18, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010022

D’Errico A, Nasso R, Ruggiero M, Rullo R, De Vendittis E, Masullo M, Mazzeo F, Arcone R. Polyphenol-Enriched Extracts from Leaves of Mediterranean Plants as Natural Inhibitors of Monoamine Oxidase (MAO)-A and MAO-B Enzymes. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Errico, Antonio, Rosarita Nasso, Mario Ruggiero, Rosario Rullo, Emmanuele De Vendittis, Mariorosario Masullo, Filomena Mazzeo, and Rosaria Arcone. 2026. "Polyphenol-Enriched Extracts from Leaves of Mediterranean Plants as Natural Inhibitors of Monoamine Oxidase (MAO)-A and MAO-B Enzymes" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010022

APA StyleD’Errico, A., Nasso, R., Ruggiero, M., Rullo, R., De Vendittis, E., Masullo, M., Mazzeo, F., & Arcone, R. (2026). Polyphenol-Enriched Extracts from Leaves of Mediterranean Plants as Natural Inhibitors of Monoamine Oxidase (MAO)-A and MAO-B Enzymes. Nutrients, 18(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010022