1. Introduction

Significant progress has been made in the management of hypertension treatment and its associated risk factors in the past few decades; however, hypertension continues to be a widespread global issue [

1]. Hypertension affects 35% of individuals in developed countries and approximately 40% in developing countries [

2]. In Pakistan, about 46% of the population is suffering from hypertension [

3]. Hypertension imposes a serious financial burden; for example, in the USA, there is a total cost of 2370 USD per patient [

4], and in Pakistan, the mean annual cost for a single hypertensive patient was approximately 321 USD [

5]. Beyond financial burden, hypertension is one of the leading causes of major health problems, including stroke, ischemic heart disease, liver dysfunction [

6], dyslipidemia [

7], imbalanced hematological profile [

8], and chronic kidney failure [

9]. Additionally, hypertension showed detrimental effects on gut microarchitecture [

10]. Although a variety of antihypertensive medications are available, their long-term use is often associated with side effects and financial burden, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, which highlights the need for safe and cost-effective solutions in hypertension management [

11]. Lifestyle factors such as physical inactivity, obesity, and unhealthy dietary habits are key modifiable risk factors that play a pivotal role in the onset and progression of hypertension [

12]. A sedentary lifestyle has been particularly identified as a key determinant, accounting for nearly 43% of hypertensive cases [

13].

Regular physical activity is emerging as one of the most effective non-pharmacological strategies for hypertension [

14]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines, 2020 recommended that at least 150 min of exercise a week is beneficial for overall health [

15]. Exercise has shown significant improvements in vascular compliance, endothelial function [

16], angiogenesis [

17], and dyslipidemia [

18] that contribute to blood pressure regulation.

In addition to physical activity, antioxidant supplementation also emerged as a novel therapy in hypertension management [

19]. Among various antioxidants, vitamin C plays a particular role due to its high potential ability to scavenge reactive oxygen species [

20], restore nitric oxide bioavailability [

21], and improve endothelial dysfunction and blood pressure [

22]. The study also indicated that low blood vitamin C levels increased the chances of hypertension [

23].

Both exercise and vitamin C improve blood pressure by reducing oxidative stress, improving endothelial function, and vascular tone. Substantial research on both interventions individually is available, but their combined effects on hypertension and related systemic and intestinal alterations remain largely unexplored. We presumed that exercise with vitamin C, in combination, could reduce the BP more efficiently. Therefore, the present study was designed to elucidate the combined effects of exercise and vitamin C supplementation on blood pressure regulation, intestinal microarchitecture, cytokine expression, hematological profile, and health markers in L-nitroarginine methyl ester (L-NAME)-induced hypertensive rats.

4. Discussion

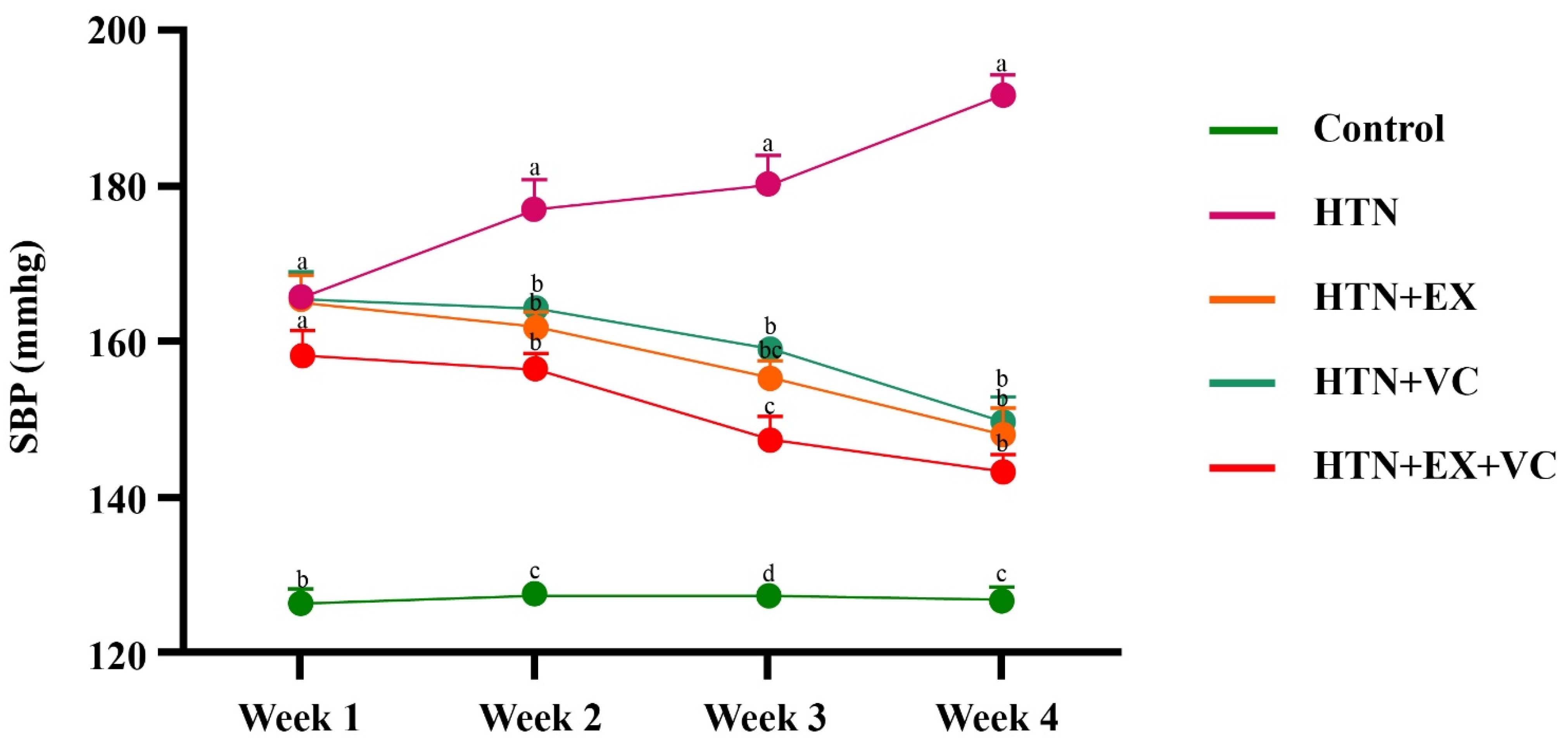

The present study demonstrates that combined exercise and vitamin C resulted in the most pronounced antihypertensive activity, which surpasses the individual benefits of both interventions alone in L-NAME-induced hypertension. The combination of exercise and vitamin C not only improved hypertension but also improved anthropometry, small intestinal microarchitecture, inflammatory gene expression, liver and lipid profile, oxidative stress, and stress hormones.

Four weeks of intervention, particularly exercise, significantly lowers body weight and body mass index and reduces the abdominal and thoracic circumferences compared to the control group. These shifts align with previous studies [

35,

36], which recognize the potential of exercise training to reduce adiposity and central measures associated with obesity, which are independent risk factors for hypertension [

37].

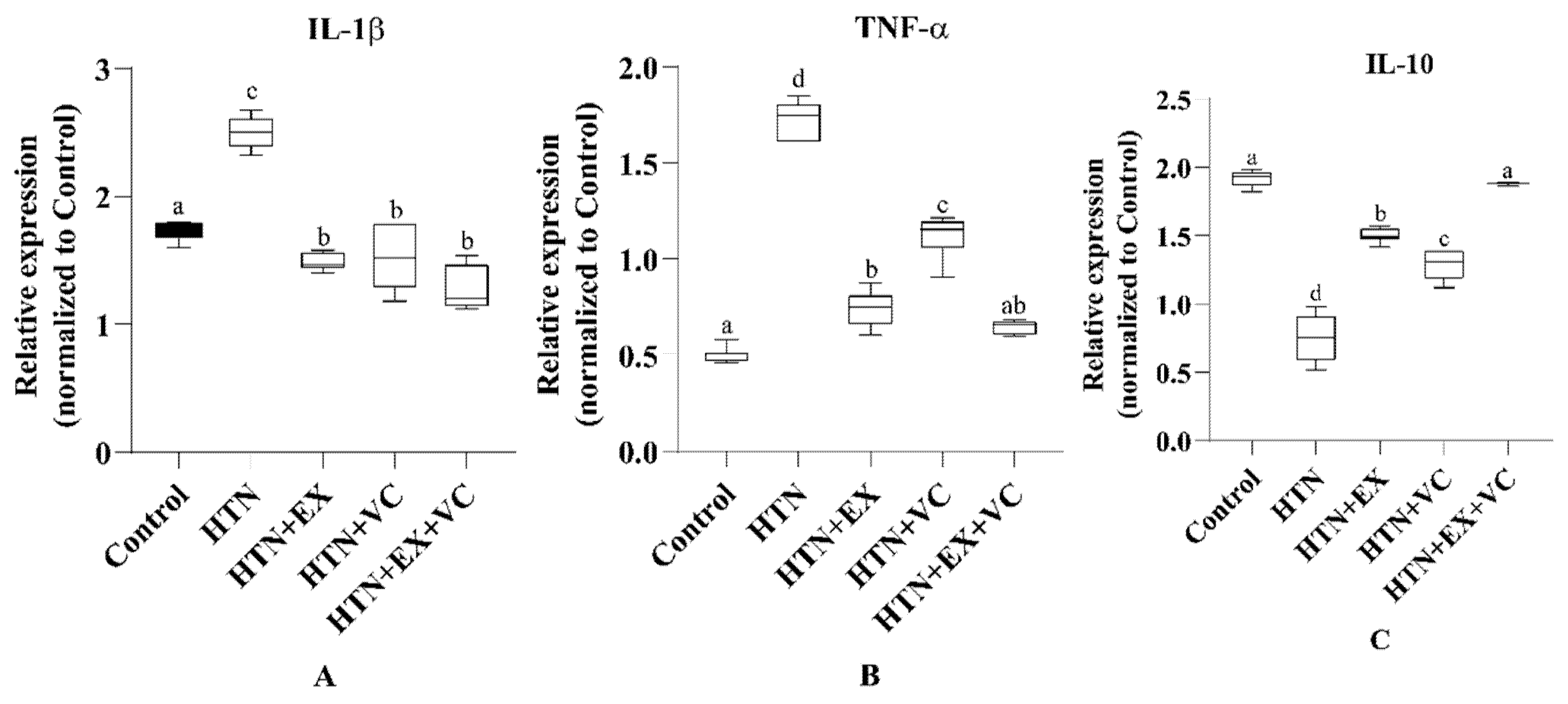

In the present study, hypertension deteriorated gut microarchitecture, which is consistent with previous studies [

34,

38]. The morphological changes are mechanistically linked to an enhanced pro-inflammatory response, which is indicated by downregulation of anti-inflammatory and upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines in intestinal tissues of the HTN group. IL-10 is a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine that normally maintains mucosal homeostasis and protects against endothelial dysfunction [

39]. The downregulation of IL-10 and upregulation of TNF-α and IL-1β show a sustained inflammatory state, which is consistent with hypertension-driven low-grade inflammation as well as increased production of trimethylamine

N-oxide (TMAO) in hypertensive models [

40,

41]. TMAO is linked with upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-1β, as well as downregulation of IL-10 [

42]. Both exercise and vitamin C intake reversed these alterations at the structural and molecular levels. Exercise significantly restored villus length and reduced the fibrotic areas of the intestine. Exercise also has downregulated TNF-α and IL-1β and upregulated IL-10, which demonstrates the well-reported antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of exercise [

43]. Similarly, vitamin C improved intestinal morphology and downregulated the pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, while upregulating IL-10 expression, which is consistent with the already reported role of vitamin C as a free radical scavenger and cytokine regulator [

44].

Hypertensive rats showed elevated WBC counts and neutrophil percentages, which is consistent with previous studies [

45,

46]. The increase in WBC might be due to hypertension-induced atherosclerosis [

47], which leads to activation of the cytokine system. Cytokines like SCF/ck repair endothelial injury, differentiate hematopoietic cells, and lead to myelopoiesis [

48]. Exercise reduced leukocytosis by attenuating the low-grade inflammation, as evidenced by low levels of CRP. This effect is primarily mediated through suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-1β, along with a decrease in levels of stress hormones like norepinephrine and cortisol [

49].

Hypertensive rats have elevated levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL, and uric acid, along with low levels of HDL, which reflect dyslipidemia and purine metabolism disturbances associated with hypertension as reported in previous studies [

50,

51]. In the exercise group, total cholesterol and triglycerides were reduced, and this effect is attributed to enhanced lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity, which hydrolyzes triglycerides into VLDL and chylomicrons and maturation of small HDL particles into larger cholesterol-rich HDL [

52]. Exercise also increases ABCA1 expression in macrophages, promoting reverse cholesterol transport, raising HDL levels, thereby reducing atherosclerosis risk [

53]. Additionally, exercise regulates nuclear receptors and lipid-related genes, including LXR [

54], ApoC3 [

55], and PCSK9 [

56], all of which improve lipid handling [

57]. Aerobic training also upregulates hepatic LDL receptors, enhancing LDL uptake and degradation [

58,

59]. Together, these mechanisms explain the observed reduction in LDL and rise in HDL, consistent with an earlier study [

60]. In the vitamin C group, total cholesterol and triglycerides were also reduced. Vitamin C supports fatty-acid β-oxidation by enhancing carnitine synthesis, which facilitates hepatic lipid metabolism [

61]. It also enhances the activity of lecithin/cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT), an enzyme central to reverse cholesterol transport, enabling cholesterol removal from tissues and excretion via the liver [

61]. While vitamin C did not significantly increase HDL, it lowered LDL, likely due to its antioxidant effect, which prevents LDL oxidation and facilitates hepatic clearance [

62]. Supporting evidence shows that vitamin C deficiency downregulates hepatic LDL receptors, leading to LDL accumulation [

63].

Uric acid levels increased in hypertensive rats, which is consistent with a previous study [

64], which may be related to renal impairments associated with hypertension. In the exercise groups, serum uric acid level was reduced, which might be due to improvement in ATP turnover. Exercise reduces adenylate deaminase, due to which precursor synthesis for uric acid production is reduced [

65], and it also improves uric acid excretion [

66]. Exercise and vitamin C showed the most favorable improvement in the atherogenic index, which shows lipid normalization aligning directly with BP reduction.

Total protein and albumin levels were elevated in hypertensive rats, as aligned with a previous study [

50]. This effect results from hemoconcentration caused by reduced plasma volume due to increased vascular tone and enhanced transcapillary fluid loss. Exercise reduces total protein and albumin levels via increased protein oxidation and amino acid metabolism as the body uses amino acids for energy and gluconeogenesis [

67].

In the present study, CRP concentrations and MDA levels were markedly elevated in hypertensive rats, reflecting the well-established link between high CRP and hypertension [

68]. Hypertension promotes vascular injury and endothelial dysfunction, which stimulate cytokine release and hepatic CRP synthesis, and CRP itself aggravates hypertension by reducing nitric oxide, enhancing oxidative stress, and creating a general inflammatory state in the body [

69]. Both exercise and vitamin C lowered CRP and MDA levels in hypertensive rats. The beneficial effects of exercise are largely attributed to its ability to reduce visceral adiposity, a major source of cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α, which in turn stimulate hepatic CRP synthesis. Exercise also lowers MDA by mitigating oxidative stress, partly through enhancing antioxidant defenses, as evidenced by the rise in catalase observed in this study [

70,

71]. Vitamin C improves the antioxidant capacity by enhancing the catalase activity, ultimately lowering lipid peroxidation and MDA levels while also preventing NF-kB activation, thereby suppressing cytokine-driven CRP synthesis [

72].

Hypertension raises the levels of norepinephrine (NE) and cortisol, which is consistent with previous studies [

73,

74]. The elevation in NE is attributed to competitive inhibition of nitric oxide synthase by L-NAME, which reduces NO availability. The absence of NO is believed to increase NE release from sympathetic nerves and adrenal medulla [

75]. Exercise reduces NE levels, while vitamin C supplementation resulted in a non-significant change compared to the HTN group. The proposed mechanism behind exercise-induced NE reduction is a rise in prostaglandin E levels, which subsequently reduces NE release from sympathetic nerves [

76]. Another proposed mechanism is that exercise reduces ouabain-like digitalis substances, which promote NE reuptake and ultimately lower plasma NE [

77]. In our study, low-intensity exercise significantly reduced circulating cortisol levels in hypertensive rats. This finding is consistent with that exercise intensity determines hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis activation. High-intensity exercise generally results in cortisol release, while low-intensity exercise causes milder neuroendocrine release and reduced HPA activation. Overall, exercise enhances cortisol clearance and tissue uptake, resulting in lower plasma cortisol levels [

78]. Moreover, the beneficial impact of exercise on stress regulation and psychological resilience, as described by Diotaiuti et al. [

79], further supports the integrative role of physical activity in maintaining cardiovascular and neuroendocrine balance. Vitamin C also lowers cortisol levels in hypertensive rats. Vitamin C shows this effect by lowering the overall oxidative stress and by interfering with the steroidogenic enzymes involved in cortisol production [

80].

5. Conclusions

Taken together, exercise and vitamin C provide broad and complementary benefits. Exercise mainly improves blood pressure by lowering stress hormones, improving lipid balance, and reducing general inflammation. Vitamin C strengthens these effects by alleviating oxidative stress, lowering inflammation, protecting the gut lining, and supporting healthier metabolism. When combined, these resulted in improved gut integrity, balanced immune responses, enhanced antioxidant status, and lowered stress hormones. These findings highlight the potential of non-pharmacological strategies, particularly regular exercise with a rich antioxidant diet, for the prevention and management of hypertension.

Among the limitations of this study, the use of an animal model, the relatively small sample size, the short intervention period, and the lack of long-term follow-up should be acknowledged. These factors may limit the generalizability of the findings and highlight the need for larger, longer-duration studies in both animal models and human populations.