1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) encompasses a group of chronic, idiopathic inflammatory disorders of the gut, primarily including ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) [

1,

2]. According to Global Burden of Disease (GBD) data, by 2021, the prevalence of IBD reached 3.83 million cases, with incidence increasing in 167 countries globally. This presents significant challenges for clinical practice, particularly as chronic inflammatory stimulation is closely linked to the development of colon cancer [

3]. A defining pathological feature of IBD is intestinal barrier dysfunction, characterized by disruption of the mucus layer and impairment of epithelial tight junctions, which facilitates microbial translocation and perpetuates mucosal inflammation [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Restoration of barrier integrity has therefore emerged as a central therapeutic strategy in IBD management [

11,

12]. The core gut probiotics—such as

Bifidobacterium,

Lactobacillus,

Clostridium butyricum [

13,

14],

A. muciniphila, and short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing bacteria, including

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and

Roseburia spp. [

15,

16]—significantly contribute to the maintenance of intestinal barrier integrity. Among these,

A. muciniphila, a key mucin-degrading bacterium, plays a significant role in maintaining intestinal barrier function and regulating host metabolism [

17].

A. muciniphila degrades intestinal mucin via the action of glycosidases, proteases, and sialidases [

18,

19], metabolizes SCFAs, and provides energy to intestinal goblet cells. This metabolic activity contributes to an increase in the thickness of the intestinal mucus layer, thereby enhancing the overall integrity of the intestinal barrier [

20,

21]. A recent study reported that

A. muciniphila subjected to pasteurization exhibits a greater ability to improve metabolic diseases compared to its active bacterial form [

22]. This suggests that the functional components of

A. muciniphila may be crucial to its probiotic effects. Amuc_1100, a 32 kDa outer membrane protein encoded by a type IV pilus gene cluster, is the most abundant and well-characterized protein of

A. muciniphila [

23]. As a postbiotic, Amuc_1100 exerts multiple health-regulating effects, including alleviation of intestinal inflammation and enhancement of barrier function through modulation of the CREBH–IGF signaling pathway [

24]. In addition, Amuc_1100 displays dual immunomodulatory activities by regulating inflammatory cytokine production via Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 (TLR2/TLR4) [

25] and reshaping the intestinal immune microenvironment through upregulation of PD-1 expression, suppression of CD8

+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte activation, and reduction in pro-inflammatory macrophage populations [

26]. Owing to these properties, Amuc_1100 has emerged as a promising postbiotic candidate with pharmaceutical and nutraceutical potential. However, its practical application is limited by the strict anaerobic growth requirements of

A. muciniphila and its dependence on mucin as the sole nutrient source, leading to complex purification procedures and high production costs [

27]. As a result, heterologous expression has become the primary strategy for Amuc_1100 production, with

Escherichia coli being the most commonly used expression system in experimental studies [

28,

29]. However, the high purification costs, potential chemical residues, and biosafety risks associated with this production method make it unsuitable for large-scale industrial applications in food and drug production.

Moreover, the location of protein expression in engineered strains significantly impacts its efficacy. Intracellular expression of functional proteins can mitigate environmental interference, enhance yield and stability, and is frequently utilized for industrial enzyme production and protein storage [

30,

31]. In contrast, secreted expression facilitates correct protein folding by releasing proteins into the extracellular space, thereby promoting precise functionality; however, this approach is limited by poor resistance to external environmental conditions. Surface display systems, which promote the adhesion properties and immune antigenicity of recombinant strains, are primarily used in vaccine development [

32,

33], but this method may induce metabolic stress and perturb the membrane structure of the vector. Therefore, a strategic selection of the expression system is essential, tailored to specific needs and applications.

In recent years, probiotics have been extensively studied as carriers for the delivery of functional proteins. As a group of microorganisms that have coexisted with humans in food systems and the gastrointestinal tract for millennia, the vast majority of lactic acid bacteria are classified as Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) by regulatory authorities [

34]. Additionally, their typical utilization in live bacterial form enables targeted delivery to the intestinal tract, allowing them to integrate and exert synergistic effects with exogenous functionalities while retaining their inherent probiotic properties [

35,

36].

Lc. paracasei L9 is a lactic acid bacterium isolated from the intestines of elderly individuals, known for its various physiological regulatory effects. Notably, it demonstrates resilience to acid and bile salt stress to a certain extent [

37,

38], which provides a distinct advantage for its application as a probiotic. Previous studies have indicated that

Lc. paracasei L9 can enhance the abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria, thereby inhibiting the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway and alleviating the development of DSS-induced colitis [

39]. Additionally,

Lc. paracasei L9 has been shown to bolster innate immunity by activating TLR2 in the mucosal layer, while also inducing macrophages to produce

IL-12, which promotes Th1 polarization and thereby enhances acquired immunity [

40]. Therefore,

Lc. paracasei L9 serves as a superior vector for Amuc_1100 expression, enabling targeted delivery of the protein to the host colon and facilitating synergistic functional enhancement.

While the therapeutic potential of Amuc_1100 is evident, its optimal delivery platform remains unexplored. Heterologous expression in E. coli faces challenges in biosafety and purification cost, limiting its application in functional foods or live biotherapeutics. Furthermore, the functional outcome of a protein therapeutic is often dictated by its spatial presentation and accessibility in the gut environment. To date, however, few studies have systematically compared multiple protein expression and localization strategies within the same probiotic chassis to determine how subcellular localization shapes distinct systemic versus local therapeutic outcomes in vivo. We hypothesized that the subcellular localization of Amuc_1100 within a probiotic vector would critically influence its therapeutic efficacy and functional specificity. To test this, we engineered Lacticaseibacillus paracasei L9—a strain with documented gut resilience and beneficial properties—to deliver Amuc_1100 via three distinct strategies: intracellular retention (pA-L9), extracellular secretion (pUA-L9), and surface display (pUPA-L9), and systematically evaluated their effects on inflammation and intestinal barrier integrity using LPS-stimulated macrophages and a DSS-induced colitis mouse model. This comparative approach was designed to provide a scalable production strategy and to explore whether distinct subcellular localization of Amuc_1100 could dissociate systemic immunomodulatory effects from localized intestinal barrier–repair functions, with the aim of informing the development of precision microbiome-based therapies for IBD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Culture Conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in

Table S1.

Lc. paracasei L9 (CGMCC NO. 9800) was cultured in MRS (Land Bridge, Beijing, China) broth at 37 °C for 12 h.

Lactococcus lactis NZ9000 (

L. lactis NZ9000) was statically cultured in M17 (Oxoid, Unipath, Basingstoke, UK) broth, supplementing 0.5% (

w/

v) glucose (GM17) at 30 °C for 8 h.

A. muciniphila ATCC BAA-835 was grown in BHI (Land Bridge, Beijing, China) broth, supplementing 0.05% (

w/

v) cysteine in an anaerobic chamber at 37 °C for 48 h. When required, the medium was supplemented with 10 μg/mL erythromycin (Solarbio, Beijing, China) for

Lc. paracasei L9 and

L. lactis NZ9000.

2.2. Construction and Expression of Recombinant Bacteria

The gene sequence of the Amuc_1100 protein was retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology Information. A codon-optimized version of the Amuc_1100 gene (approximately 880 bp), excluding the signal peptide, was synthesized de novo (Beijing Tsingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Three sets of primers (Am-F-411 and Am-R-411, Am-F-usp45 and Am-R-411, Am-F-pgsA’ and Am-R-411) were used to amplify three segments of the Amuc_1100 protein gene sequence with different connecting gene homologous arms (

Table S2). The signal peptide gene sequence of

Lactococcus lactis MG1363 usp45 (approximately 80 bp) and the truncated pgsA’ gene sequence of

Bacillus subtilis subsp. 168 (approximately 420 bp) were also synthesized. Three sets of primers (usp45-F-411 and usp45-R-Am, usp45-F-411 and usp45-R-pgsA’, pgsA’-F-usp45 and pgsA’-R-Am) were used to clone the usp45 and pgsA’ gene sequences with different connecting gene homologous arms (

Table S2). The amplified gene sequences were cloned into the

NcoI and

HindIII (both from NEB, Beijing, China) double-digested pSIP411 plasmid using the ClonExpress Ultra One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) to construct three expression vectors for intracellular expression, secretory expression, and surface display of the Amuc_1100 protein.

The recombinant plasmids were then transformed into

L. lactis NZ9000 by electroporation using Bio-Rad Gene Pulser Xcell (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA, USA) as previously described [

41]. The correct recombinant plasmid was identified by DNA sequencing (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) [

42]. The correct recombinant plasmids were then transformed into

Lc. paracasei L9 by electroporation. All recombinant bacteria were selected on MRS agar plates containing 10 µg/mL erythromycin. Expression of the Amuc_1100 protein was verified via Western blotting analysis.

2.3. Immune Colloidal Gold Transmission Electron Microscopy

After 48 h of cultivation, the bacterial culture medium was collected and centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C using a Sorvall LYNX 4000 high-speed centrifuge (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to harvest the bacterial precipitate. Subsequently, the cells were pre-fixed at 4 °C for 15 min using an immunoelectron microscopy fixative. After fixation, the cells were blocked with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Solarbio, Beijing, China) supplemented with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The cells were incubated with a mouse anti-6×His IgG2b primary antibody (diluted 1:100; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) and a mouse-specific secondary antibody conjugated to a colloidal gold (BSZH Scientific, Beijing, China). The bacteria were centrifuged again at 3000 rpm for 15 min to collect the pellet. Finally, samples underwent standard embedding and staining procedures before Transmission Electron Microscopy observation [

43].

2.4. Effect of Recombinant Strain on Pro-Inflammatory Response in Macrophages

RAW264.7 cells (purchased from the Cell Bank, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China) were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, Biological Industries, Kibbutz Beit Haemek, Israel), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) at 37 °C in a humidified incubator (3111, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with 5% CO2. For experiments, cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well in 12-well plates and starved in serum-free DMEM for 12 h prior to treatment. The experimental groups were as follows: cells treated with DMEM complete medium without the addition of LPS and bacteria (Control), model cells treated with LPS but without bacteria (LPS), experimental cells treated with LPS and Lc. paracasei L9 with empty vector (L9), experimental cells treated with LPS and A. muciniphila (AKK), experimental cells treated with LPS and Lc. paracasei L9 expressing Amuc_1100 protein within cells (pA-L9), experimental cells treated with LPS and Lc. paracasei L9 secreting Amuc_1100 protein (pUA-L9), experimental cells treated with LPS and Lc. paracasei L9 displaying Amuc_1100 protein on surface(pUPA-L9). Subsequently, DMEM complete medium containing LPS (final concentration: 500 ng/mL) was added to each well (except for the Control group), and cells were incubated for 4 h under standard culture conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2). Recombinant bacteria to be added to each experimental group were cultured for 12 h. Subsequently, a 1 mL aliquot (1 × 109 CFU/mL) of live recombinant bacteria from each group was collected, washed three times with Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS, Solarbio, Beijing, China), and resuspended in HBSS. The bacteria were then introduced to LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells (4 h induction) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Upon completion of the experiment, cell samples from each group were collected for subsequent analysis.

2.5. Animal Experiment Design

All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Sinoresearch (Beijing) Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Approval No. ZYZC2024070002S) and were conducted in strict accordance with the internationally recognized Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 8th edition, 2011). Male 6- to 8-week-old male mice (Purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratories Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) were housed in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) barrier facility under controlled conditions (12/12 h light/dark cycle, 21 ± 1 °C ambient temperature, 50 ± 5% relative humidity) with free access to water and food. After a 7-day acclimatization period, mice were weighed and randomly allocated to experimental groups using stratified block randomization to balance baseline body weight across groups. Specifically, animals were ranked by body weight and assigned in blocks of six (one mouse per group per block) using a computer-generated random sequence. After randomization, mice were assigned to six experimental groups (

n = 6 biologically independent animals per group) as follows: healthy mice consumed regular water (Control), model mice consumed 2.5% DSS (DSS), experimental mice consumed 2.5% DSS and were administered

Lc. paracasei L9 with empty vector (L9), experimental mice consumed 2.5% DSS and were administered

A. muciniphila (AKK), experimental mice consumed 2.5% DSS and administered

Lc. paracasei L9 secreting Amuc_1100 protein (pUA-L9), experimental mice consumed 2.5% DSS and were administered

Lc. paracasei L9 displaying Amuc_1100 protein on surface (pUPA-L9). From days 0 to 21, mice of the Control and DSS groups were administered with PBS, while the L9, AKK, pUA-L9 and pUPA-L9 groups were pretreated with 200 µL 5 × 10

9 CFU per 200 μL live

Lc. paracasei L9 with empty vector,

A. muciniphila,

Lc. paracasei L9 secreting Amuc_1100 protein and

Lc. paracasei L9 displaying Amuc_1100 protein on surface suspended in PBS, respectively. From days 14 to 21, the mice (except for the Control group) were supplied with drinking water containing 2.5% DSS (freshly prepared daily) to induce IBD (

Figure S2). During the experiment, all mice were observed daily for body weight, Disease Activity Index (DAI), and general condition. The body weight (BW) loss of each mouse was expressed as a percentage relative to its baseline weight before DSS administration. Specifically, the DAI was assessed each day based on weight loss, stool consistency, and fecal occult blood, following previously described methods [

44] (

Table S3). DAI scoring was performed in a blinded manner by two independent investigators who were unaware of group allocation, and any discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Twelve hours prior to the end of the experiment, mice were fasted (food withheld). Following euthanasia via carbon dioxide asphyxiation, spleen and colon tissues were collected. Colonic tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and Carnoy’s solution (Servicebio, Wuhan, China) for histological evaluation. Based on previous studies [

45], evaluations were conducted according to the severity of inflammation, the extent of inflammation, and the degree of crypt damage. The detailed scoring criteria for colonic histopathology are summarized in

Table S4. Histological scoring was performed in a blinded manner by two independent investigators, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. PAS-positive cells were counted manually in well-oriented colonic sections by two independent investigators blinded to group allocation. For each animal, at least five randomly selected, non-overlapping fields were analyzed under ×200 magnification, and goblet cell numbers were normalized to the length of the epithelium (cells per mm). The average value from each animal was used for statistical analysis. The remaining tissue samples were immediately stored at −80 °C until analysis.

2.6. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from RAW264.7 cells and frozen mouse colon tissue using TRIzol reagent (Tiangen, Beijing, China). The integrity of the RNA samples was assessed using an Infinite 200 PRO microplate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). The extracted RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the All-In-One Reverse Transcription Kit (abm, Vancouver, BC, Canada). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on a Roche LightCycler instrument (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) using the SYBR Green fluorescent dye method to quantify gene expression. The results were calculated using the 2

−ΔΔCt method, with GAPDH serving as the internal reference gene. The primers were synthesized by Sangon Bioengineering Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China, and the details are provided in

Tables S5 and S6.

2.7. Western Blot

Four recombinant strains, L9, pA-L9, pUA-L9 and pUPA-L9 (employed for detecting the expression of recombinant proteins), as well as mouse colon tissue samples (used to examine protein expression in colon tissues), which had reached the stationary phase of growth, were homogenized in a cell and tissue lysis buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Servicebio, Wuhan, China). The total protein concentration was determined using a BCA kit (Soleibao, Beijing, China). Subsequently, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (0.45 μm, IPVH00010, Millipore, Beijing, China). The membrane was blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) for 2 h. Then, it was incubated overnight at 4 °C with an anti-His-Tag mouse monoclonal antibody (1:5000 dilution; BioLegend, CA, USA), as well as NF-κB and pNF-κB rabbit monoclonal antibodies (1:5000 dilution; CST, Danvers, MA, USA). Afterward, the membrane was washed three times with TBST and incubated at room temperature for 1 h with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:5000 dilution; Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA) and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:5000 dilution; Zsbio, Beijing, China). Finally, detection was carried out using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent (Epizyme, Shanghai, China). Protein bands were visualized using an appropriate detection system (Amersham Imager 600, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). The density of the protein bands was analyzed with ImageJ analysis software (version 1.53, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), and protein abundance was normalized against β-actin.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Data were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test and for homogeneity of variances prior to statistical analysis. When these assumptions were satisfied, differences among multiple groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Post hoc comparisons were performed using Duncan’s multiple range test to identify differences between groups. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

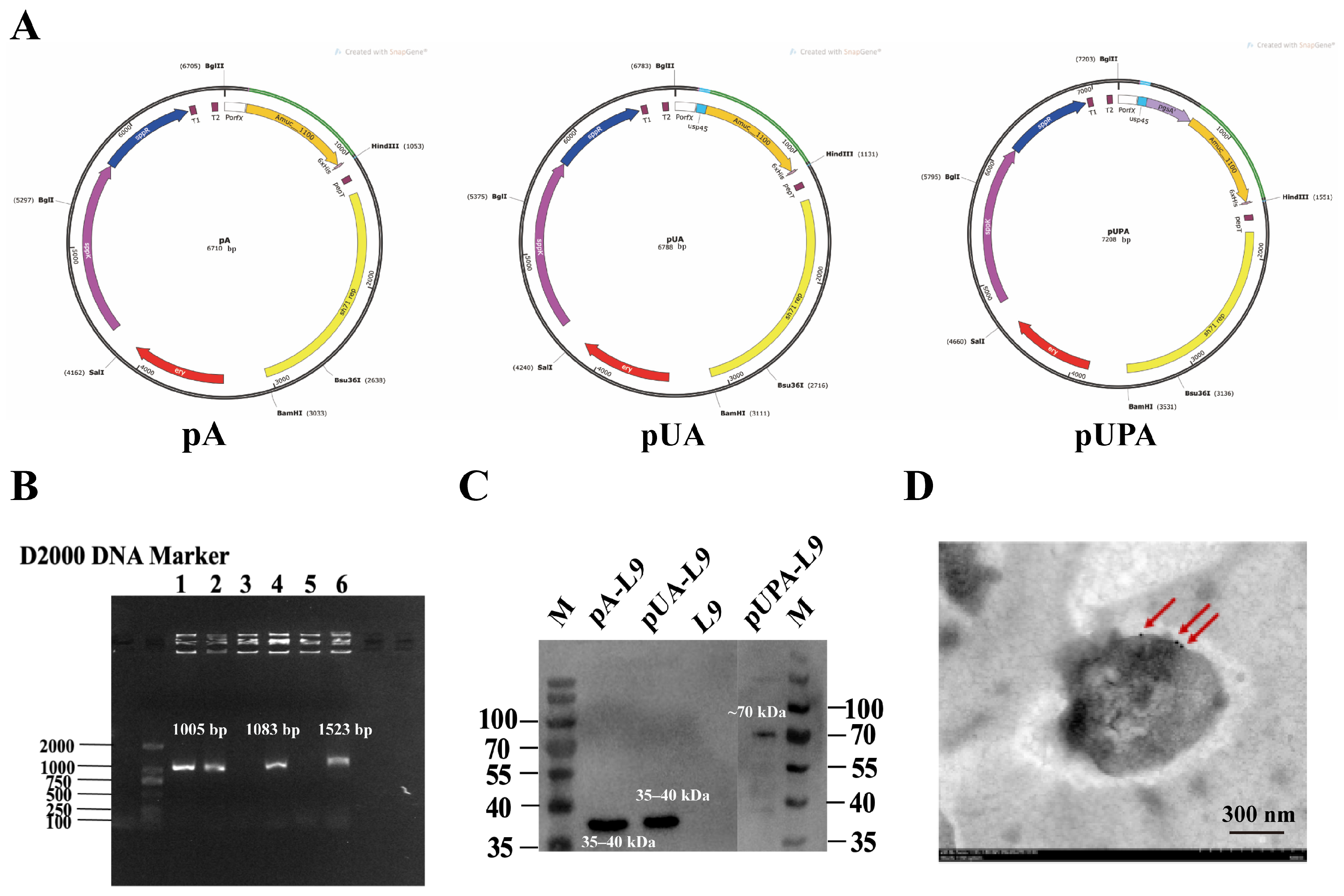

3.1. Expression and Detection of Amuc_1100 in Lc. paracasei L9 Recombinant Strains

To evaluate the expression of Amuc_1100 in

Lc. paracasei L9, three recombinant vectors—intracellular (pA-L9), secretory (pUA-L9), and surface-display (pUPA-L9)—were constructed and transformed into the host strain. Positive recombinant clones selected on erythromycin-containing plates were verified by plasmid sequencing, which confirmed correct insertions. All recombinant plasmids were verified by full-length Sanger sequencing of the inserted regions to confirm correct assembly, in-frame fusion, and sequence fidelity, with no mutations detected. Electrophoretic analysis of extracted plasmids revealed successful vector integration in lanes 1, 2, 4, and 6 (

Figure 1B), corresponding to pA-L9 (intracellular), pUA-L9 (secretory), and pUPA-L9 (surface-display) constructs.

Western blot analysis demonstrated successful Amuc_1100 expression across all three systems (

Figure 1C). Specifically, the protein was detected in cell lysates of pA-L9 (intracellular expression), culture supernatants of pUA-L9 (secretory expression), and cell wall fractions of pUPA-L9 (surface-display).

To confirm surface localization of Amuc_1100 in pUPA-L9 (surface-display) recombinants, immunogold labeling coupled with transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed. Distinct gold particle labeling on the bacterial surface (

Figure 1D) confirmed that Amuc_1100 was successfully anchored to the bacterial surface via the pUPA-L9 system.

Taken together, these findings highlight that Lc. paracasei L9 efficiently expressed and localized Amuc_1100 via intracellular, secretory, and surface-display mechanisms.

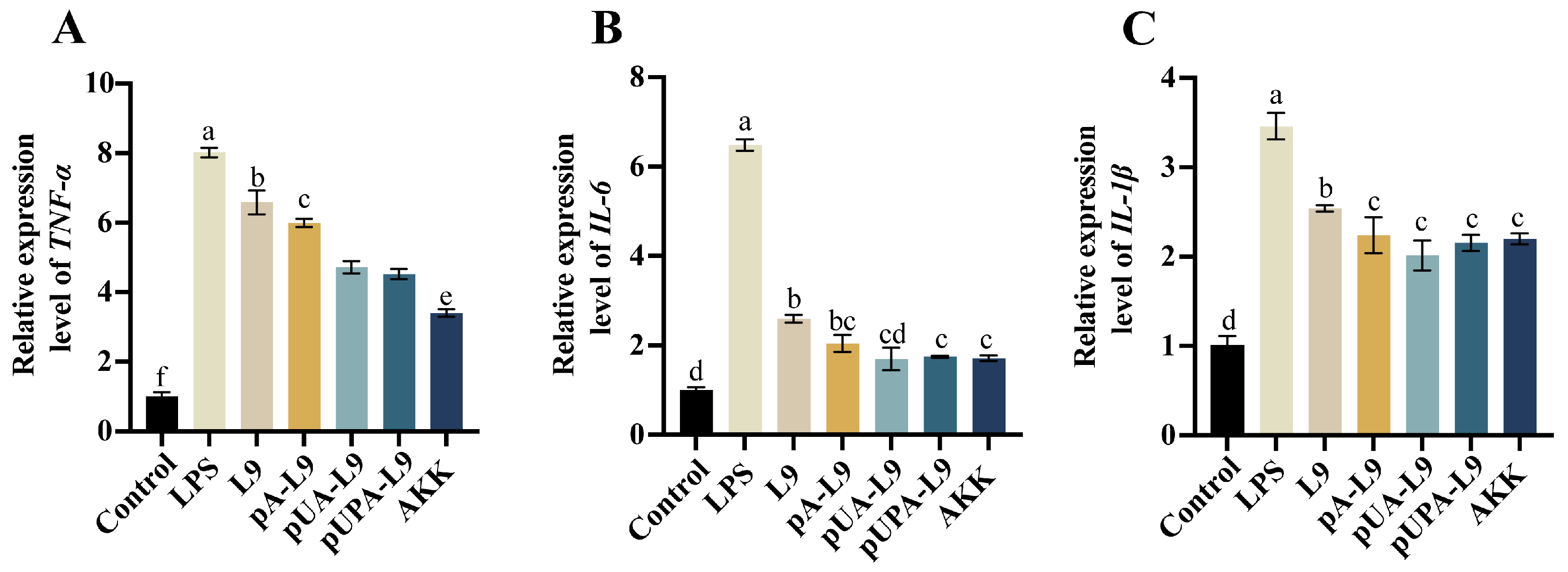

3.2. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Lc. paracasei L9 Recombinant Strains on Macrophages

To evaluate the anti-inflammatory potential of

Lc. paracasei L9 recombinants expressing Amuc_1100 protein, RAW264.7 macrophages were stimulated with LPS to induce pro-inflammatory responses. The effects of three recombinant strains—intracellular (pA-L9), secretory (pUA-L9), and surface-display (pUPA-L9)—on mRNA levels of

TNF-α,

IL-6, and

IL-1β were analyzed (

Figure 2A–C).

LPS treatment significantly upregulated

TNF-α,

IL-6, and

IL-1β expression compared to the Control group (

Figure 2A–C). All recombinant strains reduced LPS-induced cytokine expression relative to the LPS group. Notably, strains expressing Amuc_1100 protein exhibited enhanced anti-inflammatory activity compared to the

Lc. paracasei L9 with empty vector (L9).

The recombinant strain expressing intracellular Amuc_1100 protein (pA-L9) significantly suppressed TNF-α and IL-1β levels compared with L9, but showed no significant effect on IL-6 expression. In contrast, the recombinant Lc. paracasei L9 secreting Amuc_1100 protein (pUA-L9) markedly inhibited all three cytokines, with stronger TNF-α suppression than pA-L9. The recombinant strain displaying Amuc_1100 protein on the surface (pUPA-L9) significantly reduced TNF-α levels relative to pA-L9, but exhibited no statistical differences in IL-6 and IL-1β regulation. Compared with pUA-L9, pUPA-L9 did not show additional inhibitory advantages for any of the tested cytokines. Notably, A. muciniphila (AKK) most potently suppressed TNF-α, outperforming all recombinant strains. However, its inhibitory effects on IL-6 and IL-1β were not statistically significant when compared with pA-L9, pUA-L9, and pUPA-L9.

These findings underscore the varied anti-inflammatory effects of different Amuc_1100 expression systems, with pUA-L9 and pUPA-L9 showing the broadest cytokine inhibition among the engineered Lc. paracasei. Consequently, pUA-L9 and pUPA-L9 were selected to investigate their ameliorative effects on dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced intestinal barrier damage and colitis in murine models.

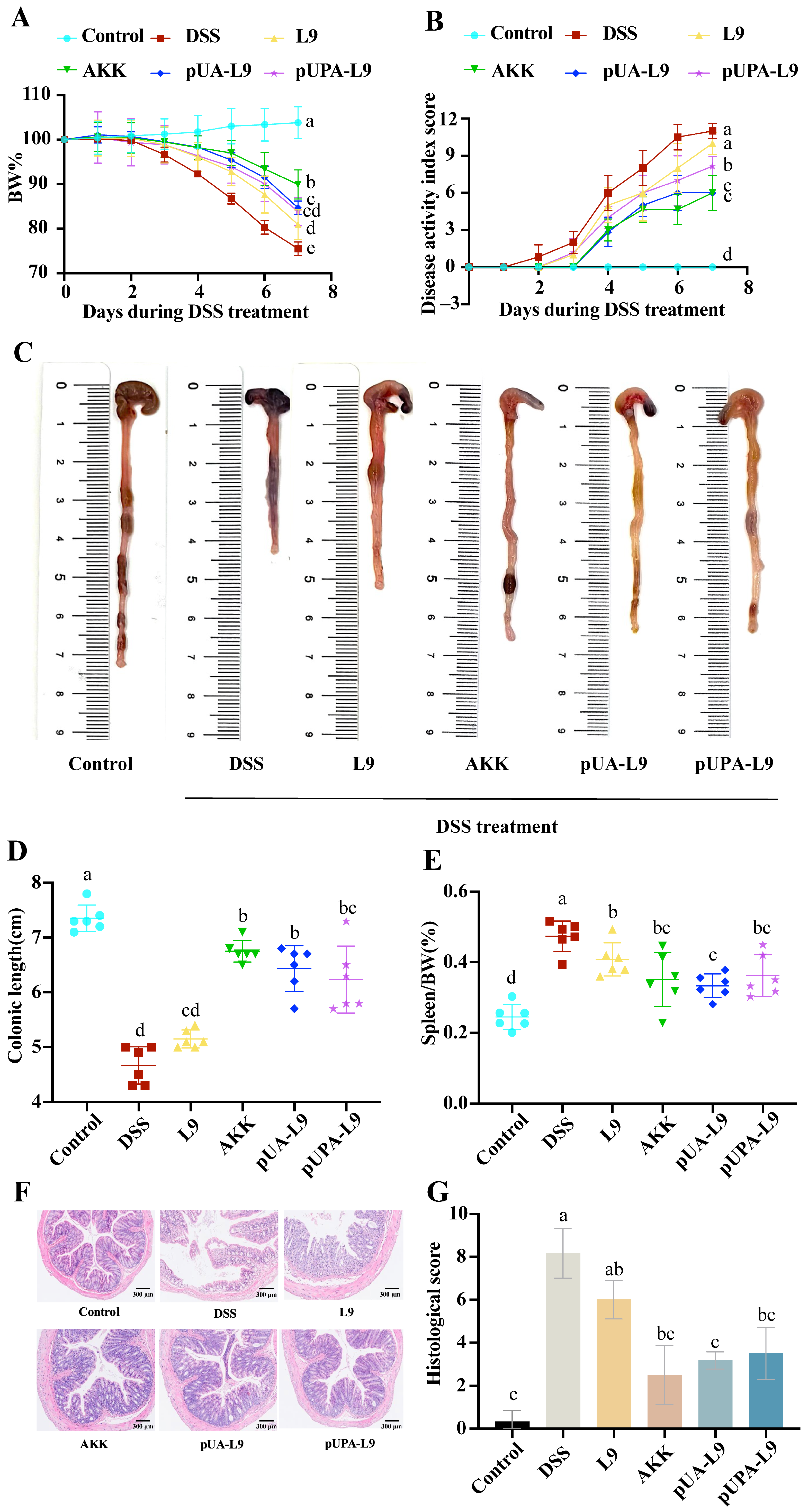

3.3. Ameliorative Effects of Lc. paracasei L9 Recombinant Strains on DSS-Induced Colitis in Mice

To evaluate the therapeutic potential of recombinant

Lc. paracasei L9 expressing Amuc_1100 protein, a dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis murine model was established. Key parameters, including body weight, disease activity index (DAI), colon length, spleen weight, and histopathological changes, were analyzed (

Figure 3A–G).

For weight loss and disease severity, DSS treatment elicited a notable 24.47 ± 1.40% reduction in body weight by day 7 alongside a corresponding elevation in DAI scores to 11.0 ± 0.63 within the DSS group—findings collectively indicative of acute colitis pathogenesis, as illustrated in

Figure 3A,B. Almost all recombinant strains demonstrated notable attenuation of DSS-induced weight loss and disease severity when compared to the DSS group. Most recombinant strains expressing Amuc_1100 conferred a more pronounced therapeutic benefit than the empty vector control (L9). Moreover, the pUA-L9 exerted a stronger suppressive effect on disease activity index (DAI) scores than pUPA-L9. Notably, native

A. muciniphila (AKK) administration markedly attenuated most disease parameters, including weight loss, disease activity index (DAI), and colon shortening.

For colon length and spleen weight, the administration of DSS induced remarkable shortening of the colon length (DSS group: 4.67 ± 0.34 cm vs. Control group: 7.35 ± 0.24 cm) and splenic edema. DSS-induced colon shortening and spleen enlargement (0.47 ± 0.04% of body weight) were markedly attenuated by pUA-L9 (

Figure 3C–E).

Lc. paracasei L9 displaying Amuc_1100 protein on the surface (pUPA-L9) showed no significant improvement in colon length or spleen weight compared to L9. H&E staining revealed severe colonic damage in DSS-treated mice, including crypt loss, epithelial disruption, and submucosal inflammatory infiltration (

Figure 3F,G). Tissue injury scores were highest in the DSS group (8.17 ± 1.17), while the pUA-L9, pUPA-L9, and AKK significantly reduced damage. pUPA-L9 and AKK had no significant effect compared with L9. Remarkably,

Lc. paracasei L9 secreting Amuc_1100 (pUA-L9) showed significantly lower histological scores compared to the empty vector control (L9).

The results showed that recombinant strains expressing Amuc_1100, particularly recombinant Lc. paracasei L9 secreting Amuc_1100 protein (pUA-L9), alleviated DSS-induced colitis by reducing weight loss, improving DAI scores, preserving colon length, mitigating spleen enlargement, and attenuating histopathological damage. These findings preliminarily suggested that the secretory delivery of Amuc_1100 (pUA-L9) might offer broad systemic benefits, while the surface-displayed form (pUPA-L9) showed a distinct profile, prompting further investigation into their mechanistic differences.

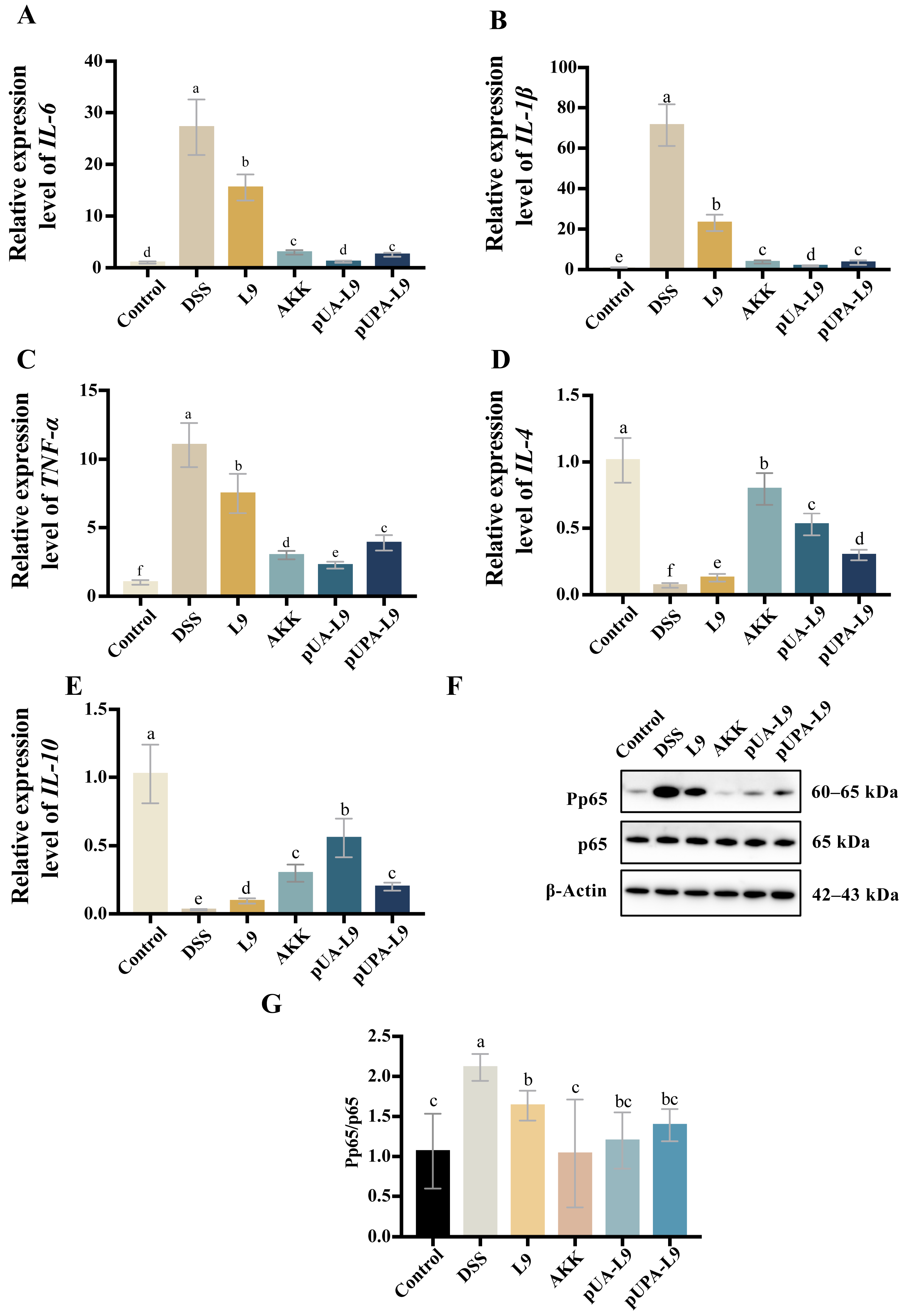

3.4. Modulation of Inflammatory Cytokines and NF-κB Signaling by Lc. paracasei L9 Recombinant Strains in Colitis Mice

To assess the anti-inflammatory mechanisms of recombinant

Lc. paracasei L9 expressing Amuc_1100 protein, mRNA levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (

IL-6,

TNF-α, and

IL-1β) and anti-inflammatory cytokines (

IL-4 and

IL-10) were measured in colon tissues of DSS-induced colitis mice (

Figure 4A–E). Additionally, phosphorylated NF-κB p65 levels were analyzed via Western blot (

Figure 4F,G).

DSS treatment significantly elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines (

IL-6,

TNF-α, and

IL-1β) and suppressed anti-inflammatory cytokines (

IL-4 and

IL-10) compared to the Control group (

Figure 4A–E). All recombinant

Lc. paracasei L9 and

A. muciniphila (AKK) attenuated these effects. Compared to the

Lc. paracasei L9 with empty vector (L9), recombinant

Lc. paracasei L9 expressing Amuc_1100 protein (pUA-L9 and pUPA-L9) and AKK further reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines and enhanced

IL-4 and

IL-10 levels. Remarkably, Recombinant

Lc. paracasei L9 secreting Amuc_1100 protein (pUA-L9) exhibited the strongest suppression of

IL-6,

IL-1β, and

TNF-α (

p < 0.05) and the highest induction of

IL-10 (

Figure 4A–E). While recombinant

Lc. paracasei L9 displaying Amuc_1100 protein on the surface (pUPA-L9) showed intermediate efficacy, with no significant advantage over pUA-L9.

DSS significantly increased phosphorylated NF-κB p65 levels, indicative of pathway activation. Recombinant strains and AKK markedly reduced phosphorylation compared to the DSS group (

p < 0.05), with AKK showing the strongest inhibition (

Figure 4F,G).

Collectively, these results established pUA-L9 as a potent systemic anti-inflammatory agent, primarily through the NF-κB pathway.

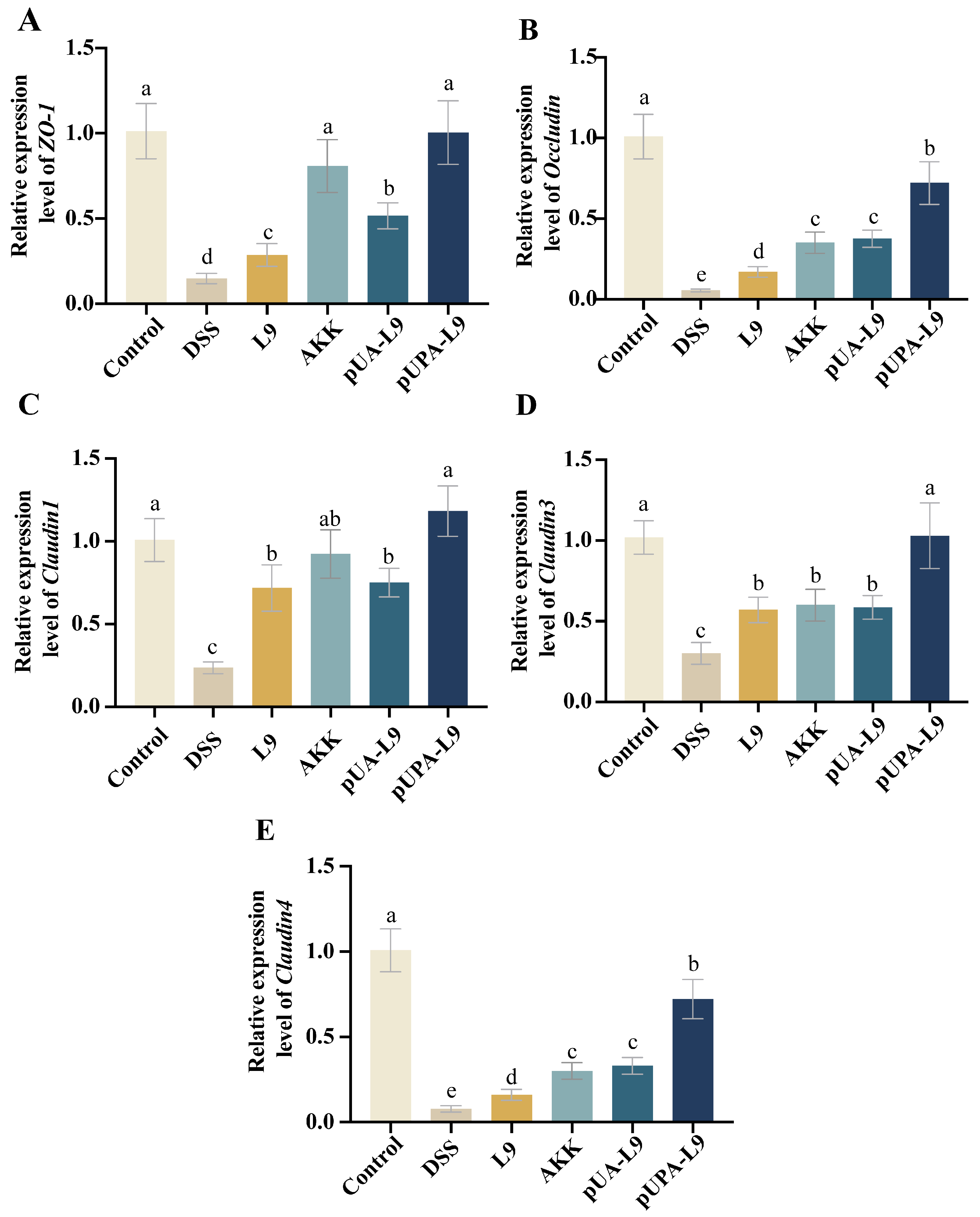

3.5. Restoration of Intestinal Tight Junction Proteins by Lc. paracasei L9 Recombinant Strains

To evaluate the impact of recombinant

Lc. paracasei L9 on intestinal barrier integrity, mRNA levels of tight junction proteins (

ZO-1,

Occludin,

Claudin1,

Claudin3, and

Claudin4) were quantified in colon tissues (

Figure 5A–E).

DSS treatment significantly downregulated all tight junction-associated markers compared to the Control group (

p < 0.05). Recombinant

Lc. paracasei L9 and

A. muciniphila (AKK) significantly restored the expression levels of these tight junction-associated markers, as demonstrated in

Figure 5A–E. Recombinant

Lc. paracasei L9 secreting Amuc_1100 protein (pUA-L9) exhibited effects comparable to AKK, both significantly inhibited the reduction in

ZO-1,

Occludin, and

Claudin4 when compared to L9. Notably, recombinant

Lc. paracasei L9, displaying Amuc_1100 protein on the surface (pUPA-L9) exhibited a pronounced advantage in upregulating expression of tight junction-associated markers, outperforming all recombinant strains and AKK.

As shown in the results, pUPA-L9 exhibited the strongest capacity to restore intestinal tight junctions, highlighting its role in preserving barrier function during colitis. This stark contrast underscores the concept that surface-display optimally positions Amuc_1100 to directly engage with and stabilize epithelial tight junctions.

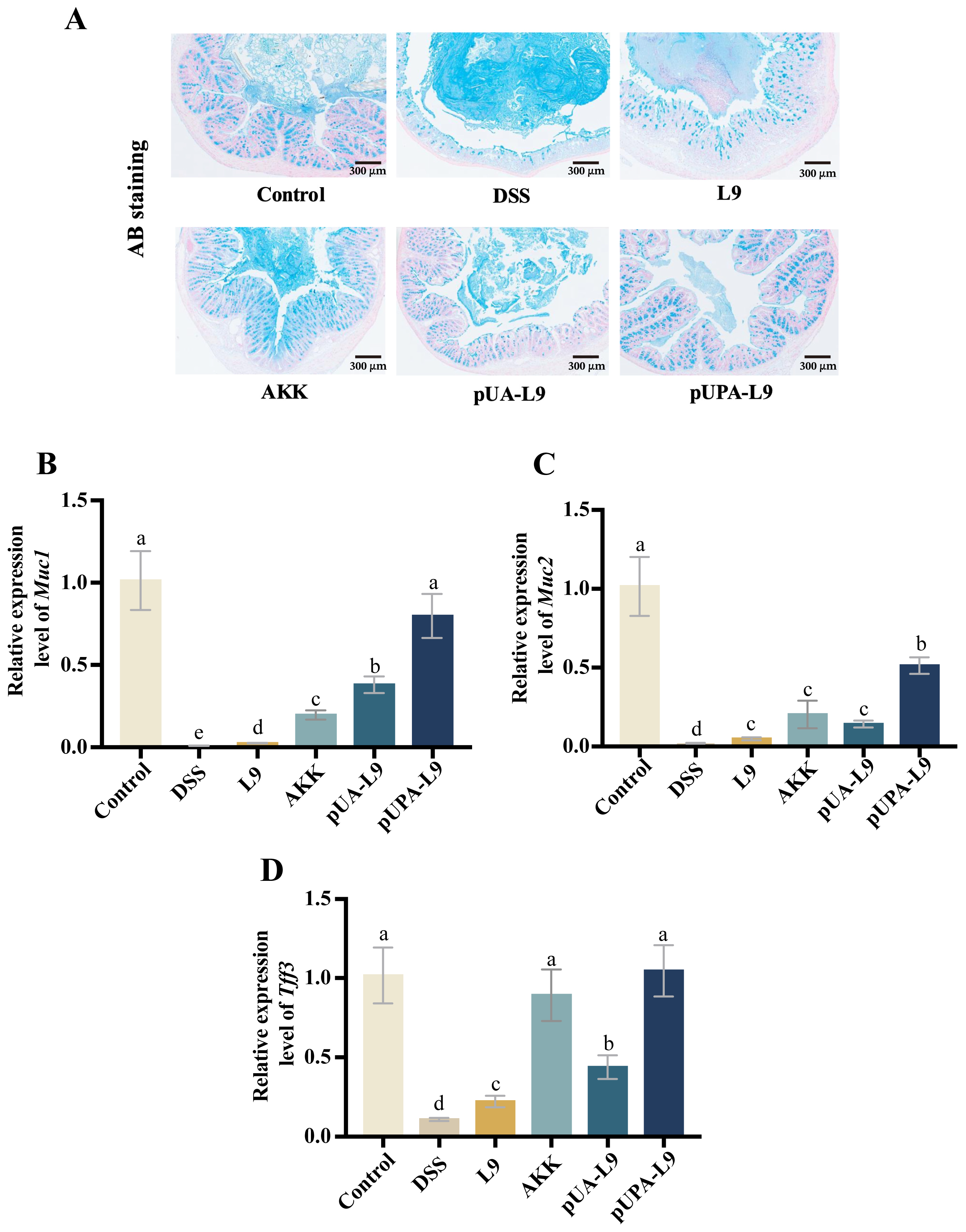

3.6. Enhancement of Colonic Mucus Barrier by Lc. paracasei L9 Recombinant Strains

To evaluate the impact of recombinant

Lc. paracasei L9 on the mucus barrier in DSS-induced colitis mice, Alcian Blue (AB) staining and gene expression quantification of mucin-associated markers (

Muc1,

Muc2, and

Tff3) were performed (

Figure 6A–D).

AB staining revealed a uniform, continuous mucus layer covering the colonic epithelium in the Control group. DSS treatment disrupted the mucus structure, resulting in a thickened, irregular, and unevenly stained layer. Recombinant

Lc. paracasei L9 secreting Amuc_1100 protein (pUA-L9),

Lc. paracasei L9 displaying Amuc_1100 protein on the surface (pUPA-L9) and

A. muciniphila (AKK) restored mucus morphology and thickness, with pUPA-L9 showing the most pronounced improvement (

Figure 6A).

DSS significantly suppressed

Muc1,

Muc2, and

Tff3 expression (

p < 0.05) when compared with the Control group. All recombinant strains and AKK mitigated these reductions. Recombinant

Lc. paracasei L9 displaying Amuc_1100 protein on the surface (pUPA-L9) exhibited the strongest efficacy, particularly in regulating

Muc1 and

Muc2 levels, outperforming other treatment groups. Compared to the

Lc. paracasei L9 with empty vector (L9), recombinant strain secreting Amuc_1100 protein (pUA-L9) also demonstrated significant upregulation of both

Muc1 and

Tff3 expression, while AKK exhibited superior efficacy in

Muc2 expression to L9 and pUA-L9 (

Figure 6B–D).

Together with the tight junction data, these findings demonstrate that pUPA-L9 improves local intestinal barrier function by enhancing both the chemical barrier (mucus-associated factors) and the physical barrier (tight junction–related markers) of the gut epithelium.

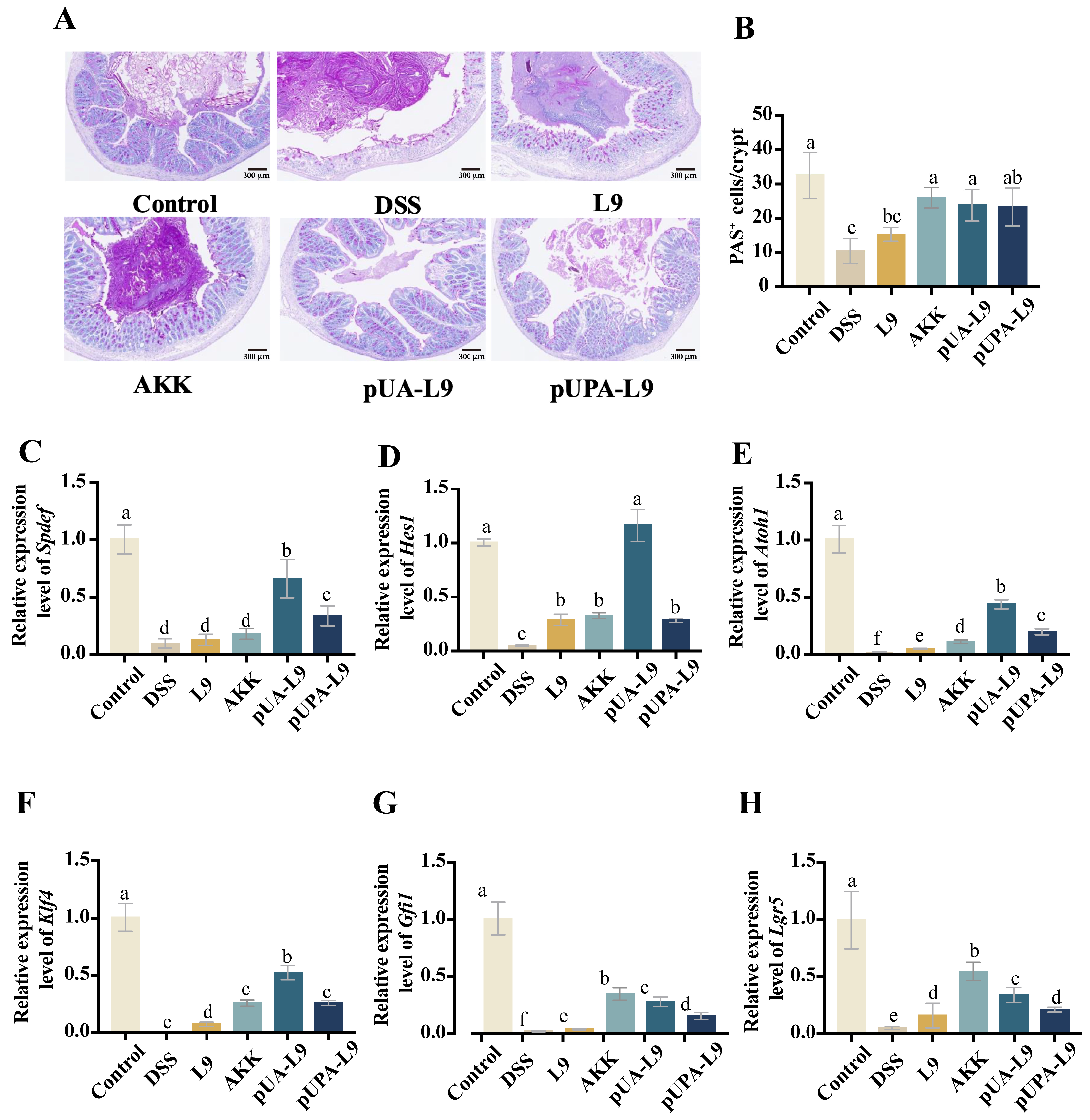

3.7. Regulation of Goblet Cell Differentiation and Maturation by Lc. paracasei L9 Recombinant Strains

The effects of recombinant

Lc. paracasei L9 on goblet cell dynamics were assessed via Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) staining and gene expression analysis of differentiation-associated markers (

Spdef,

Hes1,

Atoh1,

Klf4,

Gfi1, and

Lgr5) (

Figure 7A–H).

PAS staining revealed that DSS treatment led to a significant reduction in the number of PAS

+ goblet cells, as well as induced morphological abnormalities of mouse colon tissue (

Figure 7A,B). Recombinant

Lc. paracasei L9 and

A. muciniphila (AKK) partially restored cell numbers and morphology. Recombinant

Lc. paracasei L9 secreting Amuc_1100 protein (pUA-L9) and AKK significantly increased PAS

+ cells compared to

Lc. paracasei L9 with empty vector (L9) (

p < 0.05), while

Lc. paracasei L9 displaying Amuc_1100 protein on the surface (pUPA-L9) showed modest, non-significant improvement (

Figure 7B). Mechanistically, DSS downregulated Notch pathway regulators (

Spdef,

Hes1,

Atoh1,

Klf4, and

Gfi1) and stem cell marker

Lgr5 (

Figure 7C–H). Recombinant strains counteracted these effects. The pUPA-L9 significantly upregulated

Spdef,

Atoh1,

Klf4, and

Gfi1 compared to L9 (

p < 0.05), surpassing AKK in

Spdef,

Atoh1, and

Klf4 regulation. pUA-L9 exhibited the strongest efficacy, particularly in regulating

Spdef,

Hes1,

Atoh1, and

Klf4 levels, outperforming other treatment groups. Notably, the induction of

Hes1 expression by pUA-L9 was approximately fourfold higher than that observed in the pUPA-L9 group, while both pUA-L9 and pUPA-L9 restored

Lgr5 expression, with pUA-L9 showing stronger efficacy than pUPA-L9 (

Figure 7F).

This unique ability of pUA-L9 to promote goblet cell differentiation and epithelial regeneration, likely mediated by soluble signaling, complements its systemic anti-inflammatory effects.

4. Discussion

This study investigates whether the subcellular localization of the postbiotic protein Amuc_1100 within a probiotic chassis influences its therapeutic profile in DSS-induced colitis. By expressing Amuc_1100 intracellularly (pA-L9), extracellularly (pUA-L9), or as a surface-displayed protein (pUPA-L9) in Lc. paracasei L9, we aimed to explore whether different delivery strategies are associated with distinct biological outcomes in vivo. Rather than demonstrating categorical superiority of one strategy over another, our findings suggest that secretory and surface-display expression of Amuc_1100 confer largely comparable overall efficacy, while exhibiting different functional tendencies across immune modulation and epithelial barrier–related endpoints.

Consistent with previous reports highlighting the advantages of most lactic acid bacteria (LAB) as delivery vehicles for therapeutic proteins,

Lc. paracasei L9 represents an appropriate and well-established probiotic chassis for intestinal delivery applications [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. LAB are known to exhibit intrinsic resistance to gastrointestinal stressors and well-documented immunomodulatory properties, making them suitable hosts for proof-of-concept studies investigating the spatial delivery of bioactive molecules. While

Lactococcus lactis is frequently used as a recombinant chassis, its limited colonization capacity contrasts with the broader metabolic and ecological adaptability of

Lactobacillus species, including

Lc. paracasei L9 [

53,

54,

55].

Three primary strategies exist for recombinant protein expression in lactic acid bacteria (LAB): intracellular retention, extracellular secretion, and surface display. These approaches differ fundamentally in protein localization, yield, bioactivity, and

in vivo efficacy. Regarding protein yield, we further confirmed that the three expression strategies differed significantly. The recombinant strain expressing Amuc_1100 intracellularly (pA-L9) produced the highest protein levels, followed by the secretory expression system (pUA-L9), whereas the surface-displayed expression system (pUPA-L9) yielded the lowest amount of Amuc_1100 (

Figure S2). Previous studies have demonstrated that different heterologous expression patterns affect the biological functions of proteins. For instance, Bahey-El-Din et al. demonstrated that secretory expression of

Listeria monocytogenes lysin O (LLO) in

Lactococcus lactis elicited stronger antigen-specific immune responses compared to intracellular expression [

56]. Similarly, Bermúdez-Humarán et al. reported that secretory delivery of human papillomavirus E7 protein in

Lactococcus lactis enhanced mucosal immunity more effectively than surface display [

57]. Building on these precedents, our study revealed that both secretory (pUA-L9) and surface-display (pUPA-L9) strategies significantly suppressed lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines (

TNF-α,

IL-6, and

IL-1β) in macrophages. Both strategies outperformed intracellular expression in this regard. This divergence may stem from the limited capacity of intracellular proteins to directly engage host cells via surface interactions [

56].

In the DSS-induced colitis model, both secretory and surface-displayed strains alleviated weight loss, disease activity index elevation, colon shortening, splenomegaly, and histological injury, with no consistent statistically significant differences between pUA-L9 and pUPA-L9 across global disease indices. Nevertheless, domain-specific trends emerged. pUA-L9 tended to associate more strongly with reduced inflammatory cytokine expression and transcriptional markers linked to goblet cell differentiation (e.g., Spdef, Hes1, Atoh1, and Klf4), whereas pUPA-L9 showed relatively higher expression of tight junction– and mucus-associated genes (Muc1, Muc2, Occludin, Claudin3, and Claudin4).

The preferential upregulation of barrier-associated markers observed with pUPA-L9 is biologically plausible in light of the known adhesive properties of Amuc_1100. This protein is a highly abundant fimbrial-like outer membrane component of

A. muciniphila and has been closely linked to bacterial adhesion [

22,

58]. Previous studies have shown that surface-displayed adhesins, including Amuc_1100, can bind O-glycans within mucins, facilitating the formation of biofilm-like structures that may enhance bacterial retention within the mucus layer and reduce clearance by intestinal peristalsis [

59]. Consistent with this concept, surface modification strategies—such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) coating—have been reported to increase mucosal retention of commensal bacteria

in vivo [

59]. Similarly, incorporation of selenium dots into the bacterial envelope of

Lc. casei enhanced therapeutic efficacy in ulcerative colitis models, underscoring the potential benefit of surface-associated modifications in strengthening host–microbe interactions [

60]. Zhang et al. further demonstrated that surface-displayed Amuc_1100 contributes to improved tight junction integrity, supporting a role for adhesion-mediated local effects on the epithelial barrier [

61].

In contrast, the secretory strain pUA-L9 was more consistently associated with systemic anti-inflammatory readouts, including reduced cytokine expression and transcriptional signatures related to epithelial renewal and goblet cell differentiation. A plausible explanation is that secreted Amuc_1100, as a soluble factor, may diffuse beyond the immediate epithelial surface and interact with immune cells or crypt-resident populations. Supporting this interpretation, Amuc_1100 has been shown to activate TLR2 and TLR4 signaling pathways in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, leading to modulation of cytokine production, including

IL-10,

IL-6,

IL-8, and

TNF-α [

25]. Nevertheless, these mechanistic considerations remain inferential, as direct evidence for differential spatial distribution, cellular targeting, or retention of secreted versus surface-anchored Amuc_1100 was not obtained in the present study.

Taken together, these findings suggest that subcellular localization of Amuc_1100 within a probiotic vector may bias therapeutic outcomes toward either systemic immunomodulation or localized barrier-associated responses, without conferring absolute or categorical superiority of one strategy over the other. Rather than defining rigid functional specialization, our data support a model in which secretory and surface-display delivery modes generate partially overlapping but functionally skewed response profiles. This conceptual framework provides a basis for tailoring probiotic delivery strategies according to disease stage—for example, favoring secretory constructs during acute inflammatory phases and surface-displayed constructs during barrier repair and remission. More broadly, the concept of spatial functionality may be applicable to other therapeutic proteins, offering a route toward more precisely engineered probiotic interventions.

Although pUPA-L9 markedly increased the expression of tight junction- and mucus-associated markers, direct functional measurements of epithelial barrier integrity (such as TEER or FITC-dextran permeability) were not performed in this study and warrant further investigation. Moreover, while our data suggest that the therapeutic effects of Amuc_1100 are spatially regulated by its subcellular localization, direct evidence of protein distribution—such as fluorescent tagging—will be required to conclusively validate the proposed spatial mechanisms of action. Further validation using human gut organoids or clinical studies will be essential to assess the translational potential and scalability of this delivery strategy. In addition, future studies should explore combinatorial expression approaches, such as co-expression of secretory and surface-displayed Amuc_1100, to achieve synergistic anti-inflammatory and barrier-restorative effects.

Despite the promising therapeutic outcomes observed in this study, important biosafety and translational considerations remain before clinical or food-related applications can be realized. In the present work, antibiotic-resistance–bearing plasmids were employed to ensure stable expression of Amuc_1100 and to enable systematic comparison of subcellular localization strategies. While appropriate for proof-of-concept studies, the use of antibiotic selection markers raises concerns regarding horizontal gene transfer within the gut microbiota and presents regulatory barriers for live biotherapeutic products and functional foods [

46,

47]. Importantly, these limitations arise from the current genetic implementation rather than the spatial delivery concept itself. In future development, antibiotic markers could be replaced with food-grade or marker-free systems, and chromosomal integration of the Amuc_1100 expression cassette could enhance genetic stability and minimize horizontal gene transfer. Moreover, combining chromosomal integration with inducible or environmentally responsive promoters may further improve safety and regulatory compliance, thereby facilitating the translational application of spatially targeted probiotic therapies.