Interdisciplinary Oral Nutrition Support and Supplementation After Hip Fracture Surgery in Older Adult Inpatients: A Global Cross-Sectional Survey (ONS-STUDY) †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Survey Development

2.3. Participants and Settings

2.4. Recruitment

2.5. Bias

2.6. Data Sources and Variables

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Face Validity

3.2. Demographics

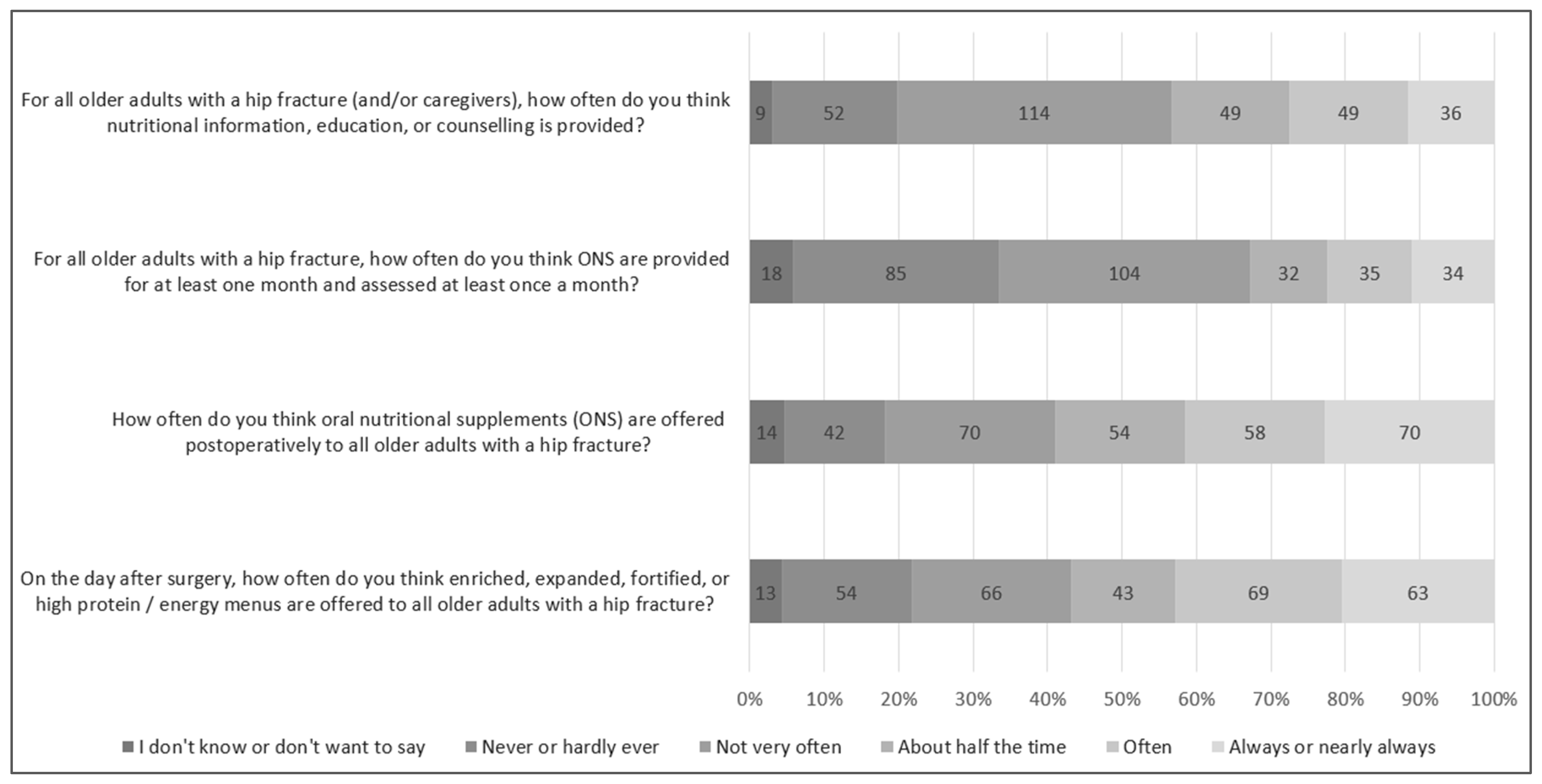

3.3. Alignment of Nutrition Support Processes to Practice Guidelines

3.4. Variation in Oral Nutritional Support Processes Across Settings

3.5. Providing Baseline Context Data to Inform and Support Future Initiatives

4. Discussion

4.1. Knowledge-to-Practice Gap One—High-Protein/Energy Choices

4.2. Knowledge-to-Practice Gap Two—ONS

4.3. Knowledge-to-Practice Gap Three—Nutrition Education

4.4. Opportunity to Improve Outcomes Through Interdisciplinary Care?

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, B.; Zhang, J.H.; Duckworth, A.D.; Clement, N.D. Effect of oral nutritional supplementation on outcomes in older adults with hip fractures and factors influencing compliance. Bone Jt. J. 2023, 105-b, 1149–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikkel, L.E.; Fox, E.J.; Black, K.P.; Davis, C.; Andersen, L.; Hollenbeak, C.S. Impact of comorbidities on hospitalization costs following hip fracture. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2012, 94, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiavarini, M.; Ricciotti, G.M.; Genga, A.; Faggi, M.I.; Rinaldi, A.; Toscano, O.D.; D’errico, M.M.; Barbadoro, P. Malnutrition-Related Health Outcomes in Older Adults with Hip Fractures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, J.; Bauer, J.; Capra, S.; Pulle, C.R. Barriers to nutritional intake in patients with acute hip fracture: Time to treat malnutrition as a disease and food as a medicine? Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2013, 91, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkert, D.; Beck, A.M.; Cederholm, T.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.; Goisser, S.; Hooper, L.; Kiesswetter, E.; Maggio, M.; Raynaud-Simon, A.; Sieber, C.C.; et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 10–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkert, D.; Beck, A.M.; Cederholm, T.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.; Hooper, L.; Kiesswetter, E.; Maggio, M.; Raynaud-Simon, A.; Sieber, C.; Sobotka, L.; et al. ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 958–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare. Hip Fracture Clinical Care Standard. ACSQHC. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/clinical-care-standards/hip-fracture-care-clinical-care-standard (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Scottish Government. Scottish Standards of Care for Hip Fracture Patients; Scottish Government: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, K.; Momosaki, R.; Yasufuku, Y.; Nakamura, N.; Maeda, K. Nutritional Therapy in Older Patients With Hip Fractures Undergoing Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 1364–1364.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.-Y.; Chiu, Y.-C.; Lu, K.-C.; Huang, I.-T.; Tsai, P.-S.; Huang, C.-J. Beneficial effects of preoperative oral nutrition supplements on postoperative outcomes in geriatric hip fracture patients: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Medicine 2021, 100, e27755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Nutrition Support in Adults: Oral Nutrition Support, Enteral Tube Feeding and Parenteral Nutrition (Clinical Guideline 32); National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- NICE. NICE Quality Standard 24: Quality Standard for Nutrition Support in Adults; NICE: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tappenden, K.A.; Quatrara, B.; Parkhurst, M.L.; Malone, A.M.; Fanjiang, G.; Ziegler, T.R. Critical Role of Nutrition in Improving Quality of Care. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2013, 37, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fragility Fracture Network. FFN Clinical Toolkit; Fragility Fracture Network: Zurich, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fragility Fracture Network. FFN Policy Toolkit; Fragility Fracture Network: Zurich, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Geirsdóttir, G.; Bell, J.J. Interdisciplinary Nutritional Management and Care for Older Adults: An Evidence-Based Practical Guide for Nurses; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; p. 271. [Google Scholar]

- Swan, W.I.; Vivanti, A.; Hakel-Smith, N.A.; Hotson, B.; Orrevall, Y.; Trostler, N.; Howarter, K.B.; Papoutsakis, C. Nutrition Care Process and Model Update: Toward Realizing People-Centered Care and Outcomes Management. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 2003–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, E.; Wright, O.R.L.; Woo, J.; Hoogendijk, E.O. Malnutrition in older adults. Lancet 2023, 401, 951–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, J.J.; Young, A.M.; Hill, J.M.; Banks, M.D.; Comans, T.A.; Barnes, R.; Keller, H.H. Systematised, Interdisciplinary Malnutrition Program for impLementation and Evaluation delivers improved hospital nutrition care processes and patient reported experiences—An implementation study. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 78, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papier, I.; Lachter, J.; Hyams, G.; Chermesh, I. Nurse’s perceptions of barriers to optimal nutritional therapy for hospitalized patients. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2017, 22, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cass, A.R.; Charlton, K.E. Prevalence of hospital-acquired malnutrition and modifiable determinants of nutritional deterioration during inpatient admissions: A systematic review of the evidence. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 35, 1043–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liljeberg, E.; Payne, L.; Josefsson, M.S.; Söderström, L.; Einarsson, S. Understanding the complexity of barriers and facilitators to adherence to oral nutritional supplements among patients with malnutrition: A systematic mixed-studies review. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANZ Hip Fracture Registry. ANZ HFR Nutrition Sprint Audit. 2022. Available online: https://anzhfr.org/sprintaudits/ (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Barry, M.J.; Edgman-Levitan, S. Shared Decision Making—The Pinnacle of Patient-Centered Care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 780–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truglio-Londrigan, M.; Slyer, J.T. Shared Decision-Making for Nursing Practice: An Integrative Review. Open Nurs. J. 2018, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, C.; Patel, S. Patient-reported outcome measures and patient-reported experience measures. BJA Educ. 2017, 17, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Our World in Data. Definitions of World Regions. 2024. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/world-region-map-definitions (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups—Country Classification by Income. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry (ANZHFR) Steering Group. Australian and New Zealand Guideline for Hip Fracture Care; Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry (ANZHFR) Steering Group: Sydney, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Iuliano, S.; Poon, S.; Robbins, J.; Bui, M.; Wang, X.; De Groot, L.; Van Loan, M.; Zadeh, A.G.; Nguyen, T.; Seeman, E. Effect of dietary sources of calcium and protein on hip fractures and falls in older adults in residential care: Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2021, 375, n2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blondal, B.; Geirsdottir, O.; Halldorsson, T.; Beck, A.; Jonsson, P.; Ramel, A. HOMEFOOD randomised trial—Six-month nutrition therapy improves quality of life, self-rated health, cognitive function, and depression in older adults after hospital discharge. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2022, 48, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinninella, E.; Raoul, P.; Maccauro, V.; Cintoni, M.; Cambieri, A.; Fiore, A.; Zega, M.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. Hospital Services to Improve Nutritional Intake and Reduce Food Waste: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neaves, B.; Bell, J.J.; McCray, S. Impact of room service on nutritional intake, plate and production waste, meal quality and patient satisfaction and meal costs: A single site pre-post evaluation. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 79, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, J.J.; Pulle, R.C.; Lee, H.B.; Ferrier, R.; Crouch, A.; Whitehouse, S.L. Diagnosis of overweight or obese malnutrition spells DOOM for hip fracture patients: A prospective audit. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 1905–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elia, M. The Cost of Malnutrition in England and Potential Cost Savings from Nutritional Interventions (Short Version): A Report on the Cost of Disease-Related Malnutrition in England and a Budget Impact Analysis of Implementing the NICE Clinical Guide-Lines/Quality Standard on Nutritional Support in Adults; NHS: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Population Review. Lactose Intolerance by Country 2024. 2024. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/lactose-intolerance-by-country (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- BAPEN. Report on UK Enteral Nutrition and Oral Nutritional Supplement Supply; BAPEN: Letchworth Garden, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Druml, C.; Ballmer, P.E.; Druml, W.; Oehmichen, F.; Shenkin, A.; Singer, P.; Soeters, P.; Weimann, A.; Bischoff, S.C. ESPEN guideline on ethical aspects of artificial nutrition and hydration. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morante, J.J.H.; Sánchez-Villazala, A.; Cutillas, R.C.; Fuentes, M.C.C. Effectiveness of a Nutrition Education Program for the Prevention and Treatment of Malnutrition in End-Stage Renal Disease. J. Ren. Nutr. 2014, 24, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuenca, M.H.; Proaño, G.V.; Blankenship, J.; Cano-Gutierrez, C.; Chew, S.T.; Fracassi, P.; Keller, H.; Mannar, M.V.; Mastrilli, V.; Milewska, M.; et al. Building Global Nutrition Policies in Health Care: Insights for Tackling Malnutrition from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2019 Global Nutrition Research and Policy. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 120, 1407–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, A.; Edwards, A.; Bauer, J.; Bell, J.J. Dietitian assistant opportunities within the nutrition care process for patients with or at risk of malnutrition: A systematic review. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 78, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cate, D.T.; Ettema, R.G.A.; Waal, G.H.; Bell, J.J.; Verbrugge, R.; Schoonhoven, L.; Schuurmans, M.J.; the Basic Care Revisited Group (BCR). Interventions to prevent and treat malnutrition in older adults to be carried out by nurses: A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 1883–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragility Fracture Network. Fragility Fracture Network Orthogeriatric Framework. 2023. Available online: https://fragilityfracturenetwork.org/ffn-resources/ (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Ekinci, O.; Yanık, S.; Bebitoğlu, B.T.; Akyüz, E.Y.; Dokuyucu, A.; Erdem, Ş. Effect of Calcium β-Hydroxy-β-Methylbutyrate (CaHMB), Vitamin D, and Protein Supplementation on Postoperative Immobilization in Malnourished Older Adult Patients With Hip Fracture. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2016, 31, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleni, A.; Panagiotis, P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of vitamin D and calcium in preventing osteoporotic fractures. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020, 39, 3571–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondanelli, M.; Faliva, M.A.; Peroni, G.; Infantino, V.; Gasparri, C.; Iannello, G.; Perna, S.; Riva, A.; Petrangolini, G.; Tartara, A. Pivotal role of boron supplementation on bone health: A narrative review. J. Trace Elements Med. Biol. 2020, 62, 126577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, J.J. Preliminary Findings of the Global ONS-Survey. In Proceedings of the Fragility Fracture Network Global Congress, Oslo, Norway, 4 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- French, S.D.; Green, S.E.; O’connor, D.A.; McKenzie, J.E.; Francis, J.J.; Michie, S.; Buchbinder, R.; Schattner, P.; Spike, N.; Grimshaw, J.M. Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: A systematic approach using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement. Sci. 2012, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grol, R.; Grimshaw, J. From best evidence to best practice: Effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet 2003, 362, 1225–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| WHO Global Region 1 | |

| Africa | 0.0 (0.0) |

| Americas | 31 (10.1) |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 2 (0.6) |

| Europe | 131 (42.5) |

| Southeast Asia | 16 (5.2) |

| Western Pacific | 127 (41.2) |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) |

| Country economic income 2,3 | |

| Low-middle and upper-middle income countries | 79 (25.6) |

| Low income | 0.0 (0.0) |

| Low-middle income | 33 (10.7) |

| Upper-middle income | 45 (14.9) |

| High income | 228 (74.0) |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) |

| Primary work setting | |

| Acute teaching hospital | 177 (57.5) |

| Acute non-teaching hospital | 54 (17.5) |

| Sub-acute or rehabilitation hospital/inpatient center | 14 (4.5) |

| Fragility fracture secondary prevention clinic | 11 (3.6) |

| Primary care setting | 8 (2.6) |

| University/academic center | 27 (8.8) |

| Government agency, policy, or health administration | 9 (2.9) |

| Other | 8 (2.6) |

| Healthcare role | |

| Medical Doctor 3 | 149 (48.4) |

| Orthopedic Surgeon | 46 (14.9) |

| [Ortho] Geriatricians | 78 (25.3) |

| Physicians/Rehabilitation Specialist/Internist | 15 (4.9) |

| General Practitioner | 5 (1.6) |

| Other | 5 (1.6) |

| Nursing Professional | 87 (28.2) |

| Allied Health Professional 3 | 55 (17.9) |

| Dietitians | 32 (10.4) |

| Physical Therapist/Physiotherapist | 21 (6.8) |

| Occupational Therapist | 1 (0.3) |

| Osteopath | 1 (0.3) |

| Research/Academic | 16 (5.2) |

| Government agency, policy, or health administration | 1 (0.3) |

| Survey Questions 1 | Median (IQR) 2 |

|---|---|

| On the day after surgery, how often do you think enriched, expanded, fortified, or high-protein/energy menus are offered to all older adults with a hip fracture? | About half the time (Not Very Often–Often) |

| How often do you think oral nutritional supplements (ONSs) are offered post-operatively to all older adults with a hip fracture? | About half the time (Not Very Often–Often) |

| For all older adults with a hip fracture, how often do you think ONS are provided for at least one month and assessed at least once a month? | Not very often (Hardly Ever or Never–About Half the Time) |

| For all older adults with a hip fracture (and/or caregivers), how often do you think nutritional information, education, or counseling is provided? | Not very often (Not very often–Often) |

| Not Often or Always * n (%) | Often or Always n (%) | Significance α | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-protein/energy choices | 175 (57.0) | 132 (43.0) | |

| Americas | 17 (54.8) | 14 (45.2) | X2(3) = 18.010; <0.001 |

| Europe 1 | 60 (45.1) | 73 (54.9) | |

| Southeast Asia | 8 (50.0) | 8 (50.0) | |

| Western Pacific | 90 (70.9) | 37 (29.1) | |

| Lower-middle and upper-middle income countries | 46 (58.2) | 33 (41.8) | X2(1) = 0.065; 0.799 |

| High-income countries | 129 (56.6)) | 99 (43.4) | |

| Oral Nutritional Supplements (ONSs) | 164 (53.4) | 143 (46.6) | |

| Americas | 18 (58.1) | 13 (41.9) | X2(3) = 12.595; 0.006 |

| Europe 1 | 60 (45.1) | 73 (54.9) | |

| Southeast Asia | 5 (31.3) | 11 (68.8) | |

| Western Pacific | 81 (63.8) | 46 (36.2) | |

| Lower-middle and upper-middle income countries | 40 (50.6) | 39 (49.4) | X2(1) = 0.332; 0.564 |

| High-income countries | 124 (54.4) | 104 (45.6) | |

| Nutrition education | 223 (72.6) | 84 (27.4) | |

| Americas | 18(58.1) | 13 (41.9) | X2(3) = 4.913; 0.178 |

| Europe 1 | 99 (74.4) | 34 (25.6) | |

| Southeast Asia | 10 (62.5) | 6 (37.5) | |

| Western Pacific | 96 (75.6) | 31 (24.4) | |

| Lower-middle and upper-middle income countries | 49 (62.0) | 30 (38.0) | X2(1) = 6.029; 0.014 |

| High-income countries | 174 (76.3) | 54 (23.7) | |

| High-protein/energy choices, ONS 2, and nutrition education | 252 (82.1) | 55 (17.9) | |

| Americas | 23 (74.2) | 8 (25.8) | X2(3) = 5.906; 0.116 |

| Europe 1 | 104 (78.2) | 29 (21.8) | |

| Southeast Asia | 13 (81.3) | 3 (18.8) | |

| Western Pacific | 112 (88.2) | 15 (11.8) | |

| Lower-middle and upper-middle income countries | 61 (77.2) | 18 (22.8) | X2(1) = 1.715; 0.190 |

| High-income countries | 191 (83.8) | 37 (16.2) |

| Survey Questions | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| With adequate training, who do you think could offer these [enriched, expanded, fortified, or high-protein/energy menus] in most cases? (Tick all that apply) | ||

| Dietitians/Nutritionists | 228 | 74.0 |

| At least one of the following healthcare workers: 1,2 | 276 | 89.6 |

| Healthcare Assistants (Medical, Nursing, or Allied Health) | 164 | 53.2 |

| Medical Doctors | 163 | 52.9 |

| Nurses | 222 | 72.1 |

| Other Allied Health Professionals | 109 | 35.4 |

| At least one of the Dietitians/Nutritionists or any other Healthcare Workers | 307 | 99.7 |

| With adequate training, who do you think could offer these oral nutritional supplements in most cases? (Tick all that apply) | ||

| Dietitians/Nutritionists | 223 | 72.4 |

| At least one of the following healthcare workers: 1,2 | 282 | 91.6 |

| Healthcare Assistants (Medical, Nursing, or Allied Health) | 150 | 48.7 |

| Medical Doctors | 188 | 61.0 |

| Nurses | 229 | 74.4 |

| Other Allied Health Professionals | 117 | 38.0 |

| At least one of the Dietitians/Nutritionists or any other Healthcare Workers | 306 | 99.4 |

| With adequate training, who do you think could assess ONS continuation in most cases? (Tick all that apply) | ||

| Dietitians/Nutritionists | 222 | 72.1 |

| At least one of the following healthcare workers: 1,2 | 272 | 88.3 |

| Healthcare Assistants (Medical, Nursing, or Allied Health) | 127 | 41.2 |

| Medical Doctors | 173 | 56.2 |

| Nurses | 202 | 65.6 |

| Other Allied Health Professionals | 116 | 37.7 |

| At least one of the Dietitians/Nutritionists or any other Healthcare Workers | 307 | 99.7 |

| With adequate training, who do you think could offer nutritional information, education, or counseling in most cases? (Tick all that apply) | ||

| Dietitians/Nutritionists | 243 | 78.9 |

| At least one of the following healthcare workers: 1,2 | 266 | 86.4 |

| Healthcare Assistants (Medical, Nursing, or Allied Health) | 126 | 40.9 |

| Medical Doctors | 186 | 60.4 |

| Nurses | 215 | 69.8 |

| Other Allied Health Professionals | 122 | 39.6 |

| At least one of the Dietitians/Nutritionists or any other Healthcare Workers | 307 | 99.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bell, J.; Turabi, R.; Olsen, S.U.; Sheehan, K.J.; Geirsdóttir, Ó.G. Interdisciplinary Oral Nutrition Support and Supplementation After Hip Fracture Surgery in Older Adult Inpatients: A Global Cross-Sectional Survey (ONS-STUDY). Nutrients 2025, 17, 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020240

Bell J, Turabi R, Olsen SU, Sheehan KJ, Geirsdóttir ÓG. Interdisciplinary Oral Nutrition Support and Supplementation After Hip Fracture Surgery in Older Adult Inpatients: A Global Cross-Sectional Survey (ONS-STUDY). Nutrients. 2025; 17(2):240. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020240

Chicago/Turabian StyleBell, Jack, Ruqayyah Turabi, Sissel Urke Olsen, Katie Jane Sheehan, and Ólöf Guðný Geirsdóttir. 2025. "Interdisciplinary Oral Nutrition Support and Supplementation After Hip Fracture Surgery in Older Adult Inpatients: A Global Cross-Sectional Survey (ONS-STUDY)" Nutrients 17, no. 2: 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020240

APA StyleBell, J., Turabi, R., Olsen, S. U., Sheehan, K. J., & Geirsdóttir, Ó. G. (2025). Interdisciplinary Oral Nutrition Support and Supplementation After Hip Fracture Surgery in Older Adult Inpatients: A Global Cross-Sectional Survey (ONS-STUDY). Nutrients, 17(2), 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020240