Diet Quality and Caloric Accuracy in AI-Generated Diet Plans: A Comparative Study Across Chatbots

Abstract

1. Introduction

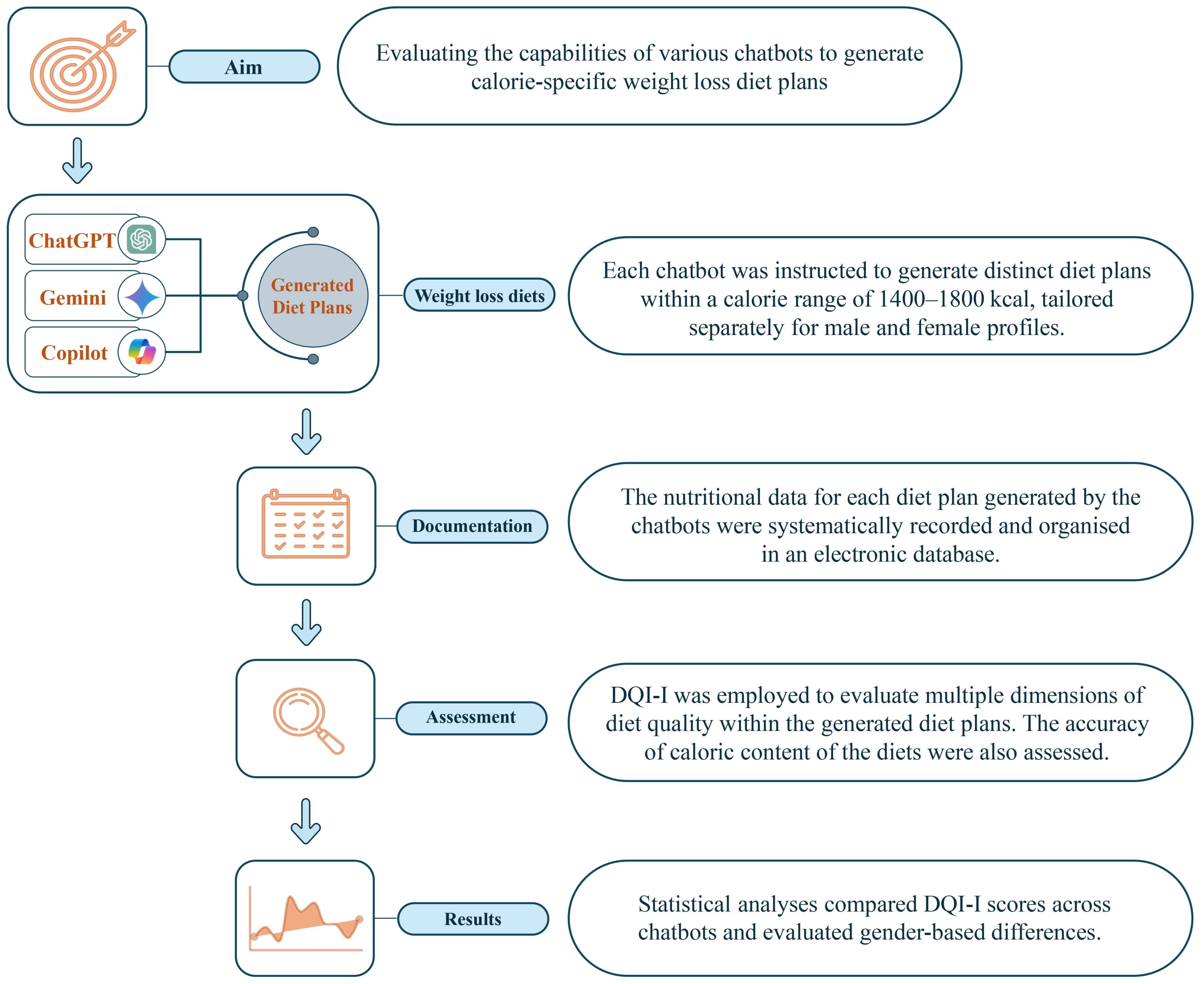

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alowais, S.A.; Alghamdi, S.S.; Alsuhebany, N.; Alqahtani, T.; Alshaya, A.I.; Almohareb, S.N.; Aldairem, A.; Alrashed, M.; Bin Saleh, K.; Badreldin, H.A.; et al. Revolutionizing healthcare: The role of artificial intelligence in clinical practice. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.; Yoon, S.N. Application of Artificial Intelligence-Based Technologies in the Healthcare Industry: Opportunities and Challenges. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Hughes, L.; Ismagilova, E.; Aarts, G.; Coombs, C.; Crick, T.; Duan, Y.; Dwivedi, R.; Edwards, J.; Eirug, A.; et al. Artificial Intelligence (AI): Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 57, 101994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.B.; Wei, W.Q.; Weeraratne, D.; Frisse, M.E.; Misulis, K.; Rhee, K.; Zhao, J.; Snowdon, J.L. Precision Medicine, AI, and the Future of Personalized Health Care. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 14, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan-Bathke, M.; Raynor, H.A.; Baxter, S.D.; Halliday, T.M.; Lynch, A.; Malik, N.; Garay, J.L.; Rozga, M. Medical Nutrition Therapy Interventions Provided by Dietitians for Adult Overweight and Obesity Management: An Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Evidence-Based Practice Guideline. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2023, 123, 520–545.e510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, C.L.; Blumberg, J.B.; El-Sohemy, A.; Minich, D.M.; Ordovás, J.M.; Reed, D.G.; Behm, V.A.Y. Toward the definition of personalized nutrition: A proposal by the American Nutrition Association. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2020, 39, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantonio, S.; Coppini, G.; Giorgi, D.; Morales, M.-A.; Pascali, M.A. Computer vision for ambient assisted living: Monitoring systems for personalized healthcare and wellness that are robust in the real world and accepted by users, carers, and society. In Computer Vision for Assistive Healthcare; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 147–182. [Google Scholar]

- Bekbolatova, M.; Mayer, J.; Ong, C.W.; Toma, M. Transformative potential of AI in Healthcare: Definitions, applications, and navigating the ethical Landscape and Public perspectives. Healthcare 2024, 12, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmanti, A.R.; Yang, H.-C.; Bintoro, B.S.; Nursetyo, A.A.; Muhtar, M.S.; Syed-Abdul, S.; Li, Y.-C.J. SlimMe, a chatbot with artificial empathy for personal weight management: System design and finding. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 870775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Olds, T.; Brinsley, J.; Dumuid, D.; Virgara, R.; Matricciani, L.; Watson, A.; Szeto, K.; Eglitis, E.; Miatke, A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of chatbots on lifestyle behaviours. NPJ Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, F. The impact of artificial intelligence on chatbot technology: A study on the current advancements and leading innovations. Eur. J. Technol. 2023, 7, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khennouche, F.; Elmir, Y.; Himeur, Y.; Djebari, N.; Amira, A. Revolutionizing generative pre-traineds: Insights and challenges in deploying ChatGPT and generative chatbots for FAQs. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 246, 123224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, A.; Tam, C.C.; Wu, D.; Li, X.; Qiao, S. Artificial Intelligence-Based Chatbots for Promoting Health Behavioral Changes: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e40789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maki, K.C.; Slavin, J.L.; Rains, T.M.; Kris-Etherton, P.M. Limitations of observational evidence: Implications for evidence-based dietary recommendations. Adv. Nutr. 2014, 5, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papastratis, I.; Konstantinidis, D.; Daras, P.; Dimitropoulos, K. AI nutrition recommendation using a deep generative model and ChatGPT. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Gaur, S. Optimizing Nutritional Outcomes: The Role of AI in Personalized Diet Planning. Int. J. Res. Publ. Semin. 2024, 15, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, E.; Won, J.; Jo, S.; Hahm, D.H.; Lee, H. Conversational Agents for Body Weight Management: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e42238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.J.; Zhang, J.; Fang, M.-L.; Fukuoka, Y. A systematic review of artificial intelligence chatbots for promoting physical activity, healthy diet, and weight loss. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, A.K.; Dhuli, K.; Donato, K.; Aquilanti, B.; Velluti, V.; Matera, G.; Iaconelli, A.; Connelly, S.T.; Bellinato, F.; Gisondi, P.; et al. Main nutritional deficiencies. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, E93–E101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines on Food Fortification with Micronutrients; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Haines, P.S.; Siega-Riz, A.M.; Popkin, B.M. The Diet Quality Index-International (DQI-I) provides an effective tool for cross-national comparison of diet quality as illustrated by China and the United States. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 3476–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, P.; McNaughton, S.A.; Livingstone, K.M.; Hadjikakou, M.; Russell, C.; Wingrove, K.; Sievert, K.; Dickie, S.; Woods, J.; Baker, P.; et al. Measuring Adherence to Sustainable Healthy Diets: A Scoping Review of Dietary Metrics. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 14, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.B. ChatGPT as a Virtual Dietitian: Exploring Its Potential as a Tool for Improving Nutrition Knowledge. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2023, 6, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, L.M.; Adam, M.T.; Whatnall, M.; Rollo, M.E.; Burrows, T.L.; Hansen, V.; Collins, C.E. Exploring the design and utility of an integrated web-based chatbot for young adults to support healthy eating: A qualitative study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2023, 20, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.W.; Park, J.S.; Sharma, K.; Velazquez, A.; Li, L.; Ostrominski, J.W.; Tran, T.; Seitter Peréz, R.H.; Shin, J.H. Qualitative evaluation of artificial intelligence-generated weight management diet plans. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1374834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzo, V.; Goitre, I.; Favaro, E.; Merlo, F.D.; Mancino, M.V.; Riso, S.; Bo, S. Is ChatGPT an Effective Tool for Providing Dietary Advice? Nutrients 2024, 16, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzo, V.; Rosato, R.; Scigliano, M.C.; Onida, M.; Cossai, S.; De Vecchi, M.; Devecchi, A.; Goitre, I.; Favaro, E.; Merlo, F.D.; et al. Comparison of the Accuracy, Completeness, Reproducibility, and Consistency of Different AI Chatbots in Providing Nutritional Advice: An Exploratory Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naja, F.; Taktouk, M.; Matbouli, D.; Khaleel, S.; Maher, A.; Uzun, B.; Alameddine, M.; Nasreddine, L. Artificial intelligence chatbots for the nutrition management of diabetes and the metabolic syndrome. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 78, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemini. Google Gemini App. Available online: https://gemini.google.com/app (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Copilot. Microsoft Copilot. Available online: https://copilot.microsoft.com/ (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- ChatGPT 4.0. Open AI ChatGPT. Available online: https://chatgpt.com/ (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Jensen, M.D.; Ryan, D.H.; Apovian, C.M.; Ard, J.D.; Comuzzie, A.G.; Donato, K.A.; Hu, F.B.; Hubbard, V.S.; Jakicic, J.M.; Kushner, R.F. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation 2014, 129, S102–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, W.T.; Mechanick, J.I.; Brett, E.M.; Garber, A.J.; Hurley, D.L.; Jastreboff, A.M.; Nadolsky, K.; Pessah-Pollack, R.; Plodkowski, R. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr. Pract. 2016, 22, 1–203. [Google Scholar]

- Carels, R.A.; Young, K.M.; Coit, C.; Clayton, A.M.; Spencer, A.; Hobbs, M. Can following the caloric restriction recommendations from the Dietary Guidelines for Americans help individuals lose weight? Eat. Behav. 2008, 9, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA. FoodData Central. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/ (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Lee, C.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Lim, C.; Jung, M. Challenges of diet planning for children using artificial intelligence. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2022, 16, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, M.; Sarani Rad, F.; Li, J. Delighting Palates with AI: Reinforcement Learning’s Triumph in Crafting Personalized Meal Plans with High User Acceptance. Nutrients 2024, 16, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosa-Holwerda, A.; Park, O.-H.; Albracht-Schulte, K.; Niraula, S.; Thompson, L.; Oldewage-Theron, W. The role of artificial intelligence in nutrition research: A scoping review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloma Krzeslak, M.; Kowalski, O. Evaluation of the compliance of diet plans and nutritional advice generated by artificial intelligence with guidelines for cardiac patients. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2024, 23, zvae098-120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanidis, K.; Tsatsou, D.; Konstantinidis, D.; Gymnopoulos, L.; Daras, P.; Wilson-Barnes, S.; Hart, K.; Cornelissen, V.; Decorte, E.; Lalama, E. PROTEIN AI advisor: A knowledge-based recommendation framework using expert-validated meals for healthy diets. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.W.; Park, C.-Y.; Shin, J.-H.; Lee, H.J. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Obesity Medicine. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armand, T.P.T.; Nfor, K.A.; Kim, J.-I.; Kim, H.-C. Applications of Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning in Nutrition: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Bisht, B.; Kumar, V.; Singh, N.; Jameel Pasha, S.B.; Singh, N.; Kumar, S. Artificial intelligence assisted food science and nutrition perspective for smart nutrition research and healthcare. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanufacturing 2024, 4, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bul, K.; Holliday, N.; Bhuiyan, M.R.A.; Clark, C.C.T.; Allen, J.; Wark, P.A. Usability and Preliminary Efficacy of an Artificial Intelligence–Driven Platform Supporting Dietary Management in Diabetes: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Hum. Factors 2023, 10, e43959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Z.; Rehm, C.D.; Rogers, G.; Ruan, M.; Wang, D.D.; Hu, F.B.; Mozaffarian, D.; Zhang, F.F.; Bhupathiraju, S.N. Trends in dietary carbohydrate, protein, and fat intake and diet quality among US adults, 1999–2016. JAMA 2019, 322, 1178–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abete, I.; Astrup, A.; Martínez, J.A.; Thorsdottir, I.; Zulet, M.A. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome: Role of different dietary macronutrient distribution patterns and specific nutritional components on weight loss and maintenance. Nutr. Rev. 2010, 68, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieronimus, B.; Hammann, S.; Podszun, M.C. Can the AI tools ChatGPT and Bard generate energy, macro- and micro-nutrient sufficient meal plans for different dietary patterns? Nutr. Res. 2024, 128, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Núñez, B.; Dijck-Brouwer, D.A.J.; Muskiet, F.A.J. The relation of saturated fatty acids with low-grade inflammation and cardiovascular disease. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 36, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, N.; Journal, A.J.E. Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for fats, including saturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, trans fatty acids, and cholesterol. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathes, D.C.; Abayasekara, D.R.E.; Aitken, R.J. Polyunsaturated fatty acids in male and female reproduction. Biol. Reprod. 2007, 77, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabozzi, G.; Iussig, B.; Cimadomo, D.; Vaiarelli, A.; Maggiulli, R.; Ubaldi, N.; Ubaldi, F.M.; Rienzi, L. The Impact of Unbalanced Maternal Nutritional Intakes on Oocyte Mitochondrial Activity: Implications for Reproductive Function. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natalucci, V.; Marmondi, F.; Biraghi, M.; Bonato, M. The Effectiveness of Wearable Devices in Non-Communicable Diseases to Manage Physical Activity and Nutrition: Where We Are? Nutrients 2023, 15, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, X. The Effects of a Low Linoleic Acid/α-Linolenic Acid Ratio on Lipid Metabolism and Endogenous Fatty Acid Distribution in Obese Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliaki, C.; Spinos, T.; Spinou, Μ.; Brinia, Μ.E.; Mitsopoulou, D.; Katsilambros, N. Defining the Optimal Dietary Approach for Safe, Effective and Sustainable Weight Loss in Overweight and Obese Adults. Healthcare 2018, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, J.A.; Navas-Carretero, S.; Saris, W.H.; Astrup, A. Personalized weight loss strategies-the role of macronutrient distribution. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhasawade, V.; Zhao, Y.; Chunara, R. Machine learning and algorithmic fairness in public and population health. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2021, 3, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, G.; Stephens, R.; Piracha, M.; Tiosano, S.; Lehouillier, F.; Koppel, R.; Elkin, P.L. The Sociodemographic Biases in Machine Learning Algorithms: A Biomedical Informatics Perspective. Life 2024, 14, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feskens, E.J.M.; Bailey, R.; Bhutta, Z.; Biesalski, H.K.; Eicher-Miller, H.; Krämer, K.; Pan, W.H.; Griffiths, J.C. Women’s health: Optimal nutrition throughout the lifecycle. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beardsworth, A.; Bryman, A.; Keil, T.; Goode, J.; Haslam, C.; Lancashire, E. Women, men and food: The significance of gender for nutritional attitudes and choices. Br. Food J. 2002, 104, 470–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, J.; Haase, A.M.; Steptoe, A.; Nillapun, M.; Jonwutiwes, K.; Bellisie, F. Gender differences in food choice: The contribution of health beliefs and dieting. Ann. Behav. Med. 2004, 27, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samad, S.; Ahmed, F.; Naher, S.; Kabir, M.A.; Das, A.; Amin, S.; Islam, S.M.S. Smartphone apps for tracking food consumption and recommendations: Evaluating artificial intelligence-based functionalities, features and quality of current apps. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2022, 15, 200103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyed, R.M. Focusing on individualized nutrition within the algorithmic diet: An in-depth look at recent advances in nutritional science, microbial diversity studies, and human health. Food Health 2023, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dergaa, I.; Saad, H.B.; Ghouili, H.; Glenn, J.M.; El Omri, A.; Slim, I.; Hasni, Y.; Taheri, M.; Aissa, M.B.; Guelmami, N. Evaluating the Applicability and Appropriateness of ChatGPT as a Source for Tailored Nutrition Advice: A Multi-Scenario Study. New Asian J. Med. 2024, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastratis, I.; Stergioulas, A.; Konstantinidis, D.; Daras, P.; Dimitropoulos, K. Can ChatGPT provide appropriate meal plans for NCD patients? Nutrition 2024, 121, 112291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niszczota, P.; Rybicka, I. The credibility of dietary advice formulated by ChatGPT: Robo-diets for people with food allergies. Nutrition 2023, 112, 112076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.L.; Chang, L.C.; Lai, I.J. Assessing the Quality of ChatGPT’s Dietary Advice for College Students from Dietitians’ Perspectives. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvaresi, D.; Eggenschwiler, S.; Calbimonte, J.-P.; Manzo, G.; Schumacher, M. A personalized agent-based chatbot for nutritional coaching. In Proceedings of the IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Web Intelligence and Intelligent Agent Technology, Melbourne, Australia, 14–17 December 2021; pp. 682–687. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Ren, P.; Wang, J.; Han, B.; ValizadehAslani, T.; Agbavor, F.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, M.; Zhao, L.; Liang, H. Leveraging GPT-4 for food effect summarization to enhance product-specific guidance development via iterative prompting. J. Biomed. Inform. 2023, 148, 104533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balloccu, S.; Reiter, E. Comparing informativeness of an NLG chatbot vs graphical app in diet-information domain. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.13435. [Google Scholar]

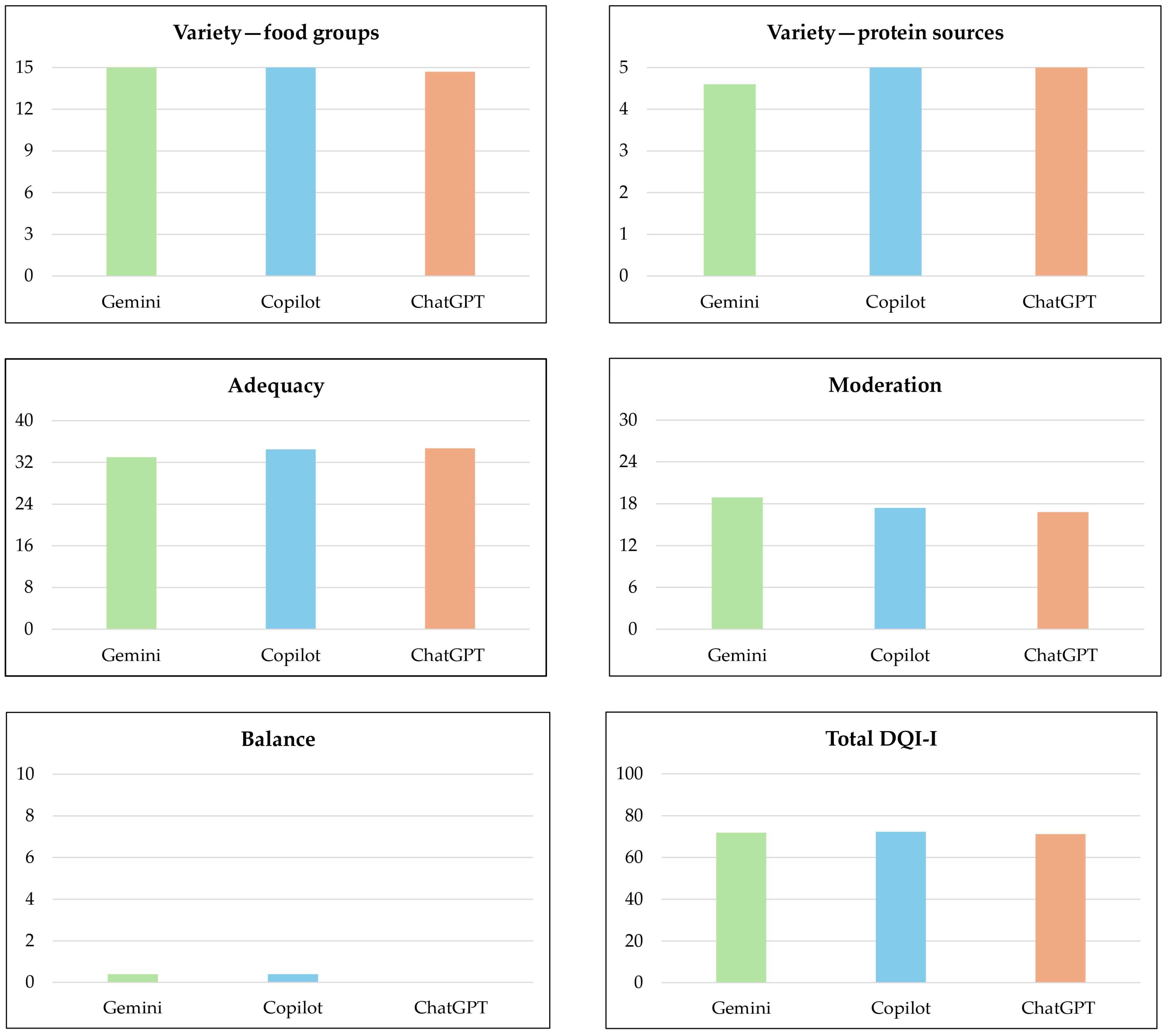

| Diet Quality Component | Grouping of Diet Quality Component | Scoring Criteria | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variety—food groups | 5 food groups: meat/poultry/fish/egg, dairy/beans, grains, fruits, and vegetables | Each food group awarded 0 or 3 pts: 3 points awarded if at least 1 item from that group was consumed | 0–15 |

| Variety—protein sources | 6 sources: meat, poultry, fish, dairy, beans, eggs | 3 or more sources consumed: 5 pts 2 sources consumed: 3 pts 1 source consumed: 1 pts 0 sources consumed: 0 pts | 0–5 |

| Adequacy | 8 groups: vegetables, fruit, grain, fibre, protein, iron, calcium, vitamin C | Between 0 and 5 points awarded for each of the 8 adequacy groups, depending on percentage of Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) met | 0–40 |

| Moderation | 6 groups: total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, sodium, empty calorie foods | Between 0 and 6 points awarded for each of the 5 moderation groups, depending on percentage of RDA met | 0–30 |

| Balance | 2 groups: macronutrient ratio, fatty acid ratio, fatty acid ratio | Between 0 and 6 points awarded depending on ratio of macronutrients, and between 0 and 4 points awarded depending on ratio of fatty acids | 0–10 |

| Chatbot | Variety—Food Groups | Variety—Protein Sources | Adequacy | Moderation | Balance | Total DQI-I Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gemini (n = 10) | 15.00 (±0.0) | 4.60 (±0.8) | 33.00 (±1.8) | 18.90 (±4.2) | 0.40 (±1.3) | 71.90 (±4.1) |

| Microsoft Copilot (n = 10) | 15.00 (±0.0) | 5.00 (±0.0) | 34.50 (±2.1) | 17.40 (±2.4) | 0.40 (±0.8) | 72.30 (±4.1) |

| ChatGPT 4.0 (n = 10) | 14.70 (±0.9) | 5.00 (±0.0) | 34.70 (±2.1) | 16.80 (±3.5) | 00.00 (±0.0) | 71.20 (±5.2) |

| Overall (n = 30) | 14.90 (±0.5) | 4.87 (±0.5) | 34.07 (±2.1) | 17.70 (±3.5) | 0.27 (±0.9) | 71.80 (±4.3) |

| Gender | Variety—Food Groups | Variety—Protein Sources | Adequacy | Moderation | Balance | Total DQI-I Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (n = 15) | 15.00 (±0.0) | 5.00 (±0.0) | 34.27 (±1.9) | 17.20 (±3.8) | 0.27 (±1.3) | 71.73 (±3.9) |

| Male (n = 15) | 14.80 (±0.7) | 4.73 (±0.7) | 33.87 (±2.3) | 18.20 (±3.1) | 0.27 (±0.7) | 71.87 (±4.9) |

| p value * | 0.040 ** | 0.002 ** | 0.579 | 0.654 | 0.895 | 0.561 |

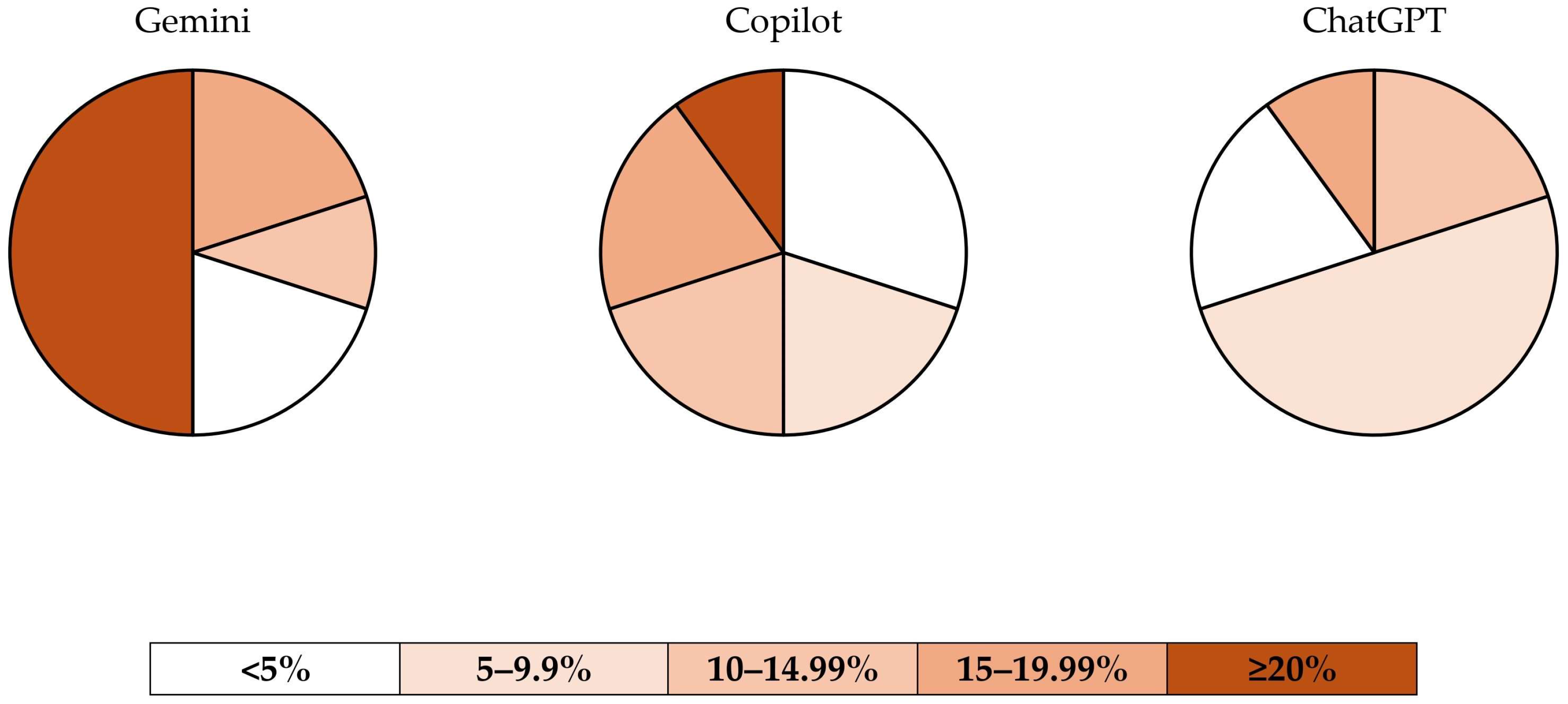

| Chatbot | <5% | 5–9.99% | 10–14.99% | 15–19.99% | ≥20% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gemini (n = 10) | n = 2 (20%) | n = 0 (0%) | n = 1 (10%) | n = 2 (20%) | n = 5 (50%) |

| Microsoft Copilot (n = 10) | n = 3 (30%) | n = 2 (20%) | n = 2 (20%) | n = 2 (20%) | n = 1 (10%) |

| ChatGPT 4.0 (n = 10) | n = 2 (20%) | n = 5 (50%) | n = 2 (20%) | n = 1 (10%) | n = 0 (0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaya Kaçar, H.; Kaçar, Ö.F.; Avery, A. Diet Quality and Caloric Accuracy in AI-Generated Diet Plans: A Comparative Study Across Chatbots. Nutrients 2025, 17, 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020206

Kaya Kaçar H, Kaçar ÖF, Avery A. Diet Quality and Caloric Accuracy in AI-Generated Diet Plans: A Comparative Study Across Chatbots. Nutrients. 2025; 17(2):206. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020206

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaya Kaçar, Hüsna, Ömer Furkan Kaçar, and Amanda Avery. 2025. "Diet Quality and Caloric Accuracy in AI-Generated Diet Plans: A Comparative Study Across Chatbots" Nutrients 17, no. 2: 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020206

APA StyleKaya Kaçar, H., Kaçar, Ö. F., & Avery, A. (2025). Diet Quality and Caloric Accuracy in AI-Generated Diet Plans: A Comparative Study Across Chatbots. Nutrients, 17(2), 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020206