Narrative Review on the Effects of Oat and Sprouted Oat Components on Blood Pressure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Searches

2.2. Study Selection

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Reviews on Oats and Blood Pressure

3.2. Human Clinical Studies on Oats and Blood Pressure

3.3. Oat Composition and Bioactives

3.4. Oat Sprouts as a Source of Bioactives

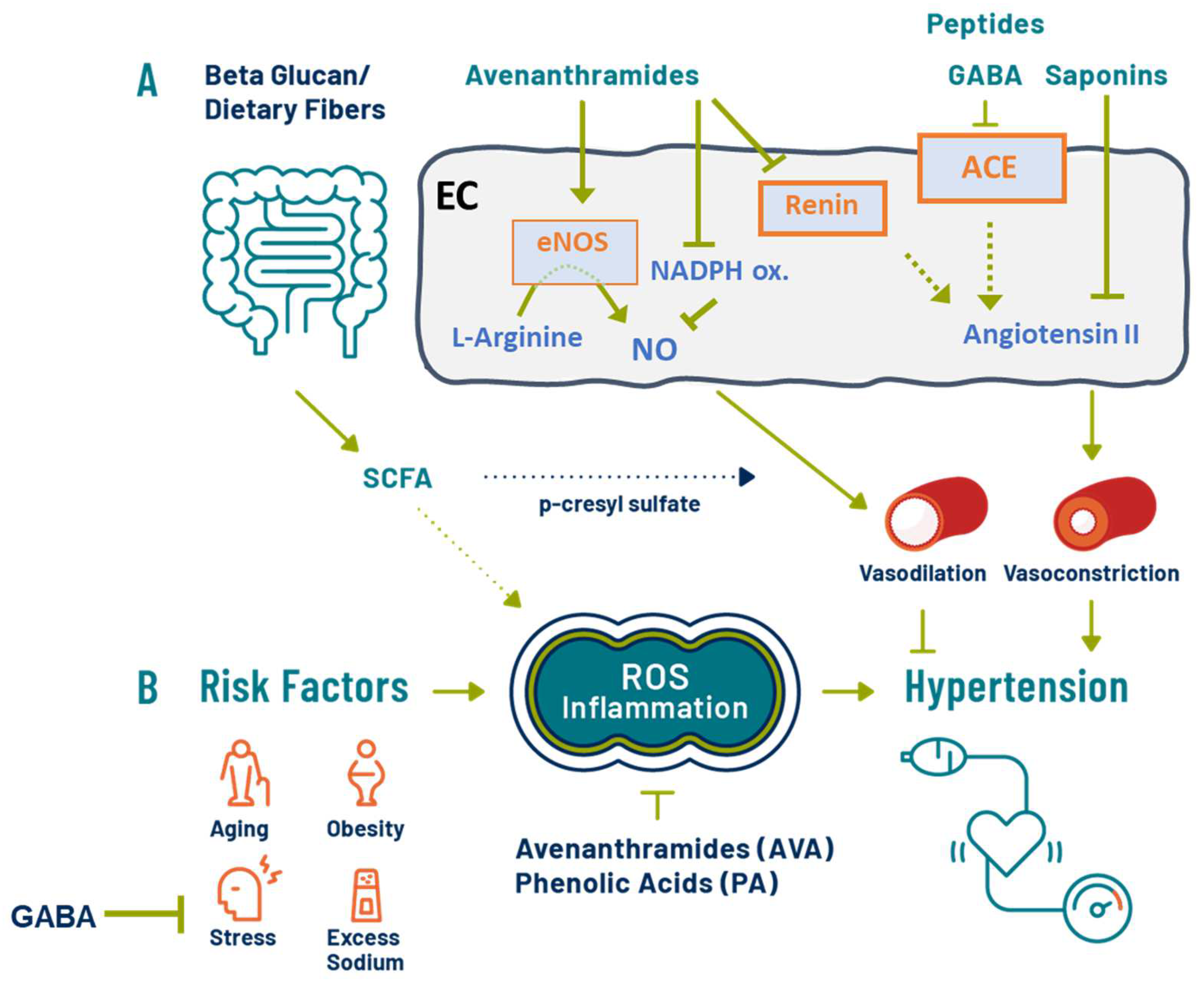

3.5. Antihypertensive Effects of Oats: Putative Mechanisms

3.6. Dietary Fiber and SCFA

3.7. Oat Phenolics and Avenanthramides

3.8. Oat Bioactive Peptides and γ-Aminobutyric Acids (GABA)

3.9. Other Oat Components: Saponin

4. Summary

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control. High Blood Pressure Symptoms and Causes. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/about.htm (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Whelton, P.K.; Carey, R.M.; Aronow, W.S.; Casey, D.E., Jr.; Collins, K.J.; Himmelfarb, C.D.; DePalma, S.M.; Gidding, S.; Jamerson, K.A.; Jones, D.W.; et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: Executive Summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2018, 138, e426–e483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrario, C.M.; Groban, L.; Wang, H.; Sun, X.; VonCannon, J.L.; Wright, K.N.; Ahmad, S. The renin–angiotensin system biomolecular cascade: A 2022 update of newer insights and concepts. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2022, 12, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neter, J.E.; Stam, B.E.; Kok, F.J.; Grobbee, D.E.; Geleijnse, J.M. Influence of Weight Reduction on Blood Pressure: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hypertension 2003, 42, 878–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahinrad, S.; Sorond, F.A.; Gorelick, P.B. Hypertension and cognitive dysfunction: A review of mechanisms, life-course observational studies and clinical trial results. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 22, 1429–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdecchia, P.; Cavallini, C.; Angeli, F. Advances in the Treatment Strategies in Hypertension: Present and Future. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2022, 9, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchard, J.; Valookaran, A.F.; Aloud, B.M.; Raj, P.; Malunga, L.N.; Thandapilly, S.J.; Netticadan, T. Impact of oats in the prevention/management of hypertension. Food Chem. 2022, 381, 132198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.E.L.; Greenwood, D.C.; Threapleton, D.E.; Cleghorn, C.L.; Nykjaer, C.; Woodhead, C.E.; Gale, C.P.; Burley, V.J. Effects of dietary fibre type on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of healthy individuals. J. Hypertens. 2015, 33, 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicero, A.F.G.; Veronesi, M.; Fogacci, F. Dietary Intervention to Improve Blood Pressure Control: Beyond Salt Restriction. High Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 2021, 28, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghi, C.; Cicero, A.F.G. Nutraceuticals with a clinically detectable blood pressure-lowering effect: A review of available randomized clinical trials and their meta-analyses. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 83, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleixandre, A.; Miguel, M. Dietary fiber and blood pressure control. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 1864–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-C.; Huang, C.-N.; Yeh, D.-M.; Wang, S.-J.; Peng, C.-H.; Wang, C.-J. Oat Prevents Obesity and Abdominal Fat Distribution, and Improves Liver Function in Humans. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2013, 68, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebello, C.J.; Johnson, W.D.; Martin, C.K.; Han, H.; Chu, Y.-F.; Bordenave, N.; Van Klinken, B.J.W.; O’Shea, M.; Greenway, F.L. Instant Oatmeal Increases Satiety and Reduces Energy Intake Compared to a Ready-to-Eat Oat-Based Breakfast Cereal: A Randomized Crossover Trial. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2016, 35, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltzman, E.; Das, S.K.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Dallal, G.E.; Corrales, A.; Schaefer, E.J.; Greenberg, A.S.; Roberts, S.B. An Oat-Containing Hypocaloric Diet Reduces Systolic Blood Pressure and Improves Lipid Profile beyond Effects of Weight Loss in Men and Women. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 1465–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouk, J.; Dekker, R.F.; Queiroz, E.A.; Barbosa-Dekker, A.M. β-Glucans as a panacea for a healthy heart? Their roles in preventing and treating cardiovascular diseases. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 177, 176–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khoury, D.; Cuda, C.; Luhovyy, B.L.; Anderson, G.H. Beta glucan: Health benefits in obesity and metabolic syndrome. J. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 2012, 851362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meydani, M. Potential health benefits of avenanthramides of oats. Nutr. Rev. 2009, 67, 731–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, R.; Kamil, A.; Chu, Y. Global review of heart health claims for oat beta-glucan products. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dioum, E.H.M.; Schneider, K.L.; Vigerust, D.J.; Cox, B.D.; Chu, Y.; Zachwieja, J.J.; Furman, D. Oats Lower Age-Related Systemic Chronic Inflammation (iAge) in Adults at Risk for Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolever, T.M.S.; Rahn, M.; Dioum, E.; Spruill, S.E.; Ezatagha, A.; Campbell, J.E.; Jenkins, A.L.; Chu, Y. An Oat β-Glucan Beverage Reduces LDL Cholesterol and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Men and Women with Borderline High Cholesterol: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 2655–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; De, S.; Belkheir, A. Avena sativa (Oat), A Potential Neutraceutical and Therapeutic Agent: An Overview. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 126–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrelli, A.; Goitre, L.; Salzano, A.M.; Moglia, A.; Scaloni, A.; Retta, S.F. Biological Activities, Health Benefits, and Therapeutic Properties of Avenanthramides: From Skin Protection to Prevention and Treatment of Cerebrovascular Diseases. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 6015351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.-S.; Hwang, C.-W.; Yang, W.-S.; Kim, C.-H. Multiple Antioxidative and Bioactive Molecules of Oats (Avena sativa L.) in Human Health. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llanaj, E.; Dejanovic, G.M.; Valido, E.; Bano, A.; Gamba, M.; Kastrati, L.; Minder, B.; Stojic, S.; Voortman, T.; Marques-Vidal, P.; et al. Effect of oat supplementation interventions on cardiovascular disease risk markers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 1749–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, K.; Jovanovski, E.; Ho, H.V.T.; Marques, A.C.R.; Zurbau, A.; Mejia, S.B.; Sievenpiper, J.L.; Vuksan, V. The effect of viscous soluble fiber on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 28, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, S.A.M.; Hartley, L.; Loveman, E.; Colquitt, J.L.; Jones, H.M.; Al-Khudairy, L.; Clar, C.; Germanò, R.; Lunn, H.R.; Frost, G.; et al. Whole grain cereals for the primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2021, CD005051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, L.; May, M.D.; Loveman, E.; Colquitt, J.L.; Rees, K. Dietary fibre for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 1, CD011472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.N.; Akerman, A.; Kumar, S.; Pham, H.T.D.; Coffey, S.; Mann, J. Dietary fibre in hypertension and cardiovascular disease management: Systematic review and meta-analyses. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pins, J.J.; Geleva, D.; Keenan, J.M.; Frazel, C.; O’Connor, P.J.; Cherney, L.M. Do whole-grain oat cereals reduce the need for antihypertensive medications and improve blood pressure control? J. Fam. Pract. 2002, 51, 353–359. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Streiffer, R.H.; Muntner, P.; Krousel-Wood, M.A.; Whelton, P.K. Effect of dietary fiber intake on blood pressure: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Hypertens. 2004, 22, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Cui, L.; Qi, J.; Ojo, O.; Du, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X. The effect of dietary fiber (oat bran) supplement on blood pressure in patients with essential hypertension: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 2458–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thies, F.; Masson, L.F.; Boffetta, P.; Kris-Etherton, P. Oats and CVD risk markers: A systematic literature review. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112 (Suppl. S2), S19–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, K.E.; Tapsell, L.C.; Batterham, M.J.; O’Shea, J.; Thorne, R.; Beck, E.; Tosh, S.M. Effect of 6 weeks’ consumption of β-glucan-rich oat products on cholesterol levels in mildly hypercholesterolaemic overweight adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, 1037–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davy, B.M.; Melby, C.L.; Beske, S.D.; Ho, R.C.; Davrath, L.R.; Davy, K.P. Oat Consumption Does Not Affect Resting Casual and Ambulatory 24-h Arterial Blood Pressure in Men with High-Normal Blood Pressure to Stage I Hypertension. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.Y.; Shen, Y.C.; Chiu, H.F.; Ten, S.M.; Lu, Y.Y.; Han, Y.C.; Venkatakrishnan, K.; Yang, S.F.; Wang, C.K. Down-regulation of partial substitution for staple food by oat noodles on blood lipid levels: A randomized, double-blind, clinical trial. J. Food Drug Anal. 2019, 27, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, K.C.; Galant, R.; Samuel, P.; Tesser, J.; Witchger, M.S.; Ribaya-Mercado, J.D.; Blumberg, J.B.; Geohas, J. Effects of consuming foods containing oat β-glucan on blood pressure, carbohydrate metabolism and biomarkers of oxidative stress in men and women with elevated blood pressure. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 786–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önning, G.; Wallmark, A.; Persson, M.; Åkesson, B.; Elmståhl, S.; Öste, R. Consumption of Oat Milk for 5 Weeks Lowers Serum Cholesterol and LDL Cholesterol in Free-Living Men with Moderate Hypercholesterolemia. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 1999, 43, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queenan, K.M.; Stewart, M.L.; Smith, K.N.; Thomas, W.; Fulcher, R.G.; Slavin, J.L. Concentrated oat β-glucan, a fermentable fiber, lowers serum cholesterol in hypercholesterolemic adults in a randomized controlled trial. Nutr. J. 2007, 6, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momenizadeh, A.; Heidari, R.; Sadeghi, M.; Tabesh, F.; Ekramzadeh, M.; Haghighatian, Z.; Golshahi, J.; Baseri, M. Effects of oat and wheat bread consumption on lipid profile, blood sugar, and endothelial function in hypercholesterolemic patients: A randomized controlled clinical trial. ARYA Atheroscler. 2014, 10, 259–265. [Google Scholar]

- Raimondi de Souza, S.; Moraes de Oliveira, G.M.; Raggio Luiz, R.; Rosa, G. Effects of oat bran and nutrition counseling on the lipid and glucose profile and anthropometric parameters of hypercholesterolemia patients. Nutr. Hosp. 2016, 33, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, J.F.; Rouse, I.L.; Curley, C.B.; Sacks, F.M. Comparison of the Effects of Oat Bran and Low-Fiber Wheat on Serum Lipoprotein Levels and Blood Pressure. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990, 322, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Song, P.; Wang, C.; Man, Q.; Meng, L.; Cai, J.; Kurilich, A. Randomized controlled trial of oatmeal consumption versus noodle consumption on blood lipids of urban Chinese adults with hypercholesterolemia. Nutr. J. 2012, 11, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfaris, N.A.; Ba-Jaber, A.S. Effects of a low-energy diet with and without oat bran and olive oil supplements on body mass index, blood pressure, and serum lipids in diabetic women: A randomized controlled trial. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 3602–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicero, A.F.; Fogacci, F.; Veronesi, M.; Strocchi, E.; Grandi, E.; Rizzoli, E.; Poli, A.; Marangoni, F.; Borghi, C. A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Medium-Term Effects of Oat Fibers on Human Health: The Beta-Glucan Effects on Lipid Profile, Glycemia and intestinal Health (BELT) Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza Leão, L.S.C.; de Aquino, L.A.; Dias, J.F.; Koifman, R.J. Addition of oat bran reduces HDL-C and does not potentialize effect of a low-calorie diet on remission of metabolic syndrome: A pragmatic, randomized, controlled, open-label nutritional trial. Nutrition 2019, 65, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damsgaard, C.T.; Biltoft-Jensen, A.P.; Tetens, I.; Michaelsen, K.F.; Lind, M.V.; Astrup, A.; Landberg, R. Whole-Grain Intake, Reflected by Dietary Records and Biomarkers, Is Inversely Associated with Circulating Insulin and Other Cardiometabolic Markers in 8- to 11-Year-Old Children. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.; Soycan, G.; Corona, G.; Johnson, J.; Chu, Y.; Shewry, P.; Lovegrove, A. Chronic Vascular Effects of Oat Phenolic Acids and Avenanthramides in Pre- or Stage 1 Hypertensive Adults. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melini, F.; Melini, V.; Luziatelli, F.; Ficca, A.G.; Ruzzi, M. Health-Promoting Components in Fermented Foods: An Up-to-Date Systematic Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Gao, F.; Zhang, X.; Wang, O.; Wu, W.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, F.; Ji, B. Evaluation of γ- aminobutyric acid, phytate and antioxidant activity of tempeh-like fermented oats (Avena sativa L.) prepared with different filamentous fungi. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 2544–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raguindin, P.F.; Itodo, O.A.; Stoyanov, J.; Dejanovic, G.M.; Gamba, M.; Asllanaj, E.; Minder, B.; Bussler, W.; Metzger, B.; Muka, T.; et al. A systematic review of phytochemicals in oat and buckwheat. Food Chem. 2021, 338, 127982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, O.; Mah, E.; Dioum, E.; Marwaha, A.; Shanmugam, S.; Malleshi, N.; Sudha, V.; Gayathri, R.; Unnikrishnan, R.; Anjana, R.M.; et al. The Role of Oat Nutrients in the Immune System: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soycan, G.; Schär, M.Y.; Kristek, A.; Boberska, J.; Alsharif, S.N.; Corona, G.; Shewry, P.R.; Spencer, J.P. Composition and content of phenolic acids and avenanthramides in commercial oat products: Are oats an important polyphenol source for consumers? Food Chem. X 2019, 3, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, S.; Idehen, E.; Zhao, Y.; Chu, Y. Emerging science on whole grain intake and inflammation. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-García, N.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Frias, J.; Crespo Perez, L.; Fernández, C.F.; Alba, C.; Rodríguez, J.M.; Peñas, E. A Novel Sprouted Oat Fermented Beverage: Evaluation of Safety and Health Benefits for Celiac Individuals. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Mao, G.; Yuan, Y.; Weng, Y.; Zhu, R.; Cai, C.; Mao, J. Optimization of oat seed steeping and germination temperatures to maximize nutrient content and antioxidant activity. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-García, N.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Frias, J.; Peñas, E. Changes in protein profile, bioactive potential and enzymatic activities of gluten-free flours obtained from hulled and dehulled oat varieties as affected by germination conditions. LWT 2020, 134, 109955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samia El-Safy, F.; Rabab, H.A.S.; Ensaf Mukhtar, Y.Y. The Impact of Soaking and Germination on Chemical Composition, Carbohydrate Fractions, Digestibility, Antinutritional Factors and Minerals Content of Some Legumes and Cereals Grain Seeds. Alex. Sci. Exch. J. 2013, 34, 499–513. [Google Scholar]

- Herreman, L.; Nommensen, P.; Pennings, B.; Laus, M.C. Comprehensive overview of the quality of plant- And animal-sourced proteins based on the digestible indispensable amino acid score. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 5379–5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.G.; Hu, Q.P.; Duan, J.L.; Tian, C.R. Dynamic Changes in γ-Aminobutyric Acid and Glutamate Decarboxylase Activity in Oats (Avena nuda L.) during Steeping and Germination. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 9759–9763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Johnson, J.; Chu, Y.F.; Feng, H. Enhancement of γ-aminobutyric acid, avenanthramides, and other health-promoting metabolites in germinating oats (Avena sativa L.) treated with and without power ultrasound. Food Chem. 2019, 283, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damazo-Lima, M.; Rosas-Pérez, G.; Reynoso-Camacho, R.; Pérez-Ramírez, I.F.; Rocha-Guzmán, N.E.; de Los Ríos, E.A.; Ramos-Gomez, M. Chemopreventive Effect of the Germinated Oat and Its Phenolic-AVA Extract in Azoxymethane/Dextran Sulfate Sodium (AOM/DSS) Model of Colon Carcinogenesis in Mice. Foods 2020, 9, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Sang, S. Quantitative Analysis and Anti-inflammatory Activity Evaluation of the A-Type Avenanthramides in Commercial Sprouted Oat Products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 13068–13075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tain, Y.-L.; Hsu, C.-N. Oxidative Stress-Induced Hypertension of Developmental Origins: Preventive Aspects of Antioxidant Therapy. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, S.; Ostfeld, R.J.; Allen, K.; Williams, K.A. A plant-based diet and hypertension. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whelton, S.P.; Hyre, A.D.; Pedersen, B.; Yi, Y.; Whelton, P.K.; He, J. Effect of dietary fiber intake on blood pressure: A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled clinical trials. J. Hypertens. 2005, 23, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streppel, M.T.; Arends, L.R.; Veer, P.V.; Grobbee, D.E.; Geleijnse, J.M. Dietary Fiber and Blood Pressure: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 165, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, D.; Dhungana, B.; Caffe, M.; Krishnan, P. A Review of Health-Beneficial Properties of Oats. Foods 2021, 10, 2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poll, B.G.; Cheema, M.U.; Pluznick, J.L. Gut Microbial Metabolites and Blood Pressure Regulation: Focus on SCFAs and TMAO. Physiology 2020, 35, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Khodor, S.; Reichert, B.; Shatat, I.F. The Microbiome and Blood Pressure: Can Microbes Regulate Our Blood Pressure? Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosola, C.; De Angelis, M.; Rocchetti, M.T.; Montemurno, E.; Maranzano, V.; Dalfino, G.; Manno, C.; Zito, A.; Gesualdo, M.; Ciccone, M.M.; et al. Beta-Glucans Supplementation Associates with Reduction in P-Cresyl Sulfate Levels and Improved Endothelial Vascular Reactivity in Healthy Individuals. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, M.; Montemurno, E.; Vannini, L.; Cosola, C.; Cavallo, N.; Gozzi, G.; Maranzano, V.; Di Cagno, R.; Gobbetti, M.; Gesualdo, L. Effect of Whole-Grain Barley on the Human Fecal Microbiota and Metabolome. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 7945–7956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Feng, M.; Chu, Y.; Wang, S.; Shete, V.; Tuohy, K.M.; Liu, F.; Zhou, X.; Kamil, A.; Pan, D.; et al. The Prebiotic Effects of Oats on Blood Lipids, Gut Microbiota, and Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Mildly Hypercholesterolemic Subjects Compared with Rice: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 787797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluznick, J.L. Microbial Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Blood Pressure Regulation. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2017, 19, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masenga, S.K.; Hamooya, B.; Hangoma, J.; Hayumbu, V.; Ertuglu, L.A.; Ishimwe, J.; Rahman, S.; Saleem, M.; Laffer, C.L.; Elijovich, F.; et al. Recent advances in modulation of cardiovascular diseases by the gut microbiota. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2022, 36, 952–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristek, A.; Wiese, M.; Heuer, P.; Kosik, O.; Schär, M.Y.; Soycan, G.; Alsharif, S.; Kuhnle, G.G.C.; Walton, G.; Spencer, J.P.E. Oat bran, but not its isolated bioactive β-glucans or polyphenols, have a bifidogenic effect in an in vitro fermentation model of the gut microbiota. Br. J. Nutr. 2019, 121, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontula, P.; von Wright, A.; Mattila-Sandholm, T. Oat bran β-gluco- and xylo-oligosaccharides as fermentative substrates for lactic acid bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1998, 45, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmu, J.; Salosensaari, A.; Havulinna, A.S.; Cheng, S.; Inouye, M.; Jain, M.; Salido, R.A.; Sanders, K.; Brennan, C.; Humphrey, G.C.; et al. Association Between the Gut Microbiota and Blood Pressure in a Population Cohort of 6953 Individuals. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e016641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, D.; Guo, Y.; Cai, H.; Liu, K.; He, Y.; Liu, Y.; Guo, L. The Effect of Lactobacillus Consumption on Human Blood Pressure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 54, 102547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Guzmán, M.; Toral, M.; Romero, M.; Jiménez, R.; Galindo, P.; Sánchez, M.; Zarzuelo, M.J.; Olivares, M.; Gálvez, J.; Duarte, J. Antihypertensive effects of probiotics Lactobacillus strains in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 2326–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, C.D.; Hooper, L.; Kroon, P.A.; Rimm, E.B.; Cassidy, A. Relative impact of flavonoid composition, dose and structure on vascular function: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials of flavonoid-rich food products. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2012, 56, 1605–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godos, J.; Vitale, M.; Micek, A.; Ray, S.; Martini, D.; Del Rio, D.; Riccardi, G.; Galvano, F.; Grosso, G. Dietary Polyphenol Intake, Blood Pressure, and Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serreli, G.; Le Sayec, M.; Thou, E.; Lacour, C.; Diotallevi, C.; Dhunna, M.A.; Deiana, M.; Spencer, J.P.E.; Corona, G. Ferulic Acid Derivatives and Avenanthramides Modulate Endothelial Function through Maintenance of Nitric Oxide Balance in HUVEC Cells. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.J.; Jung, C.W.; Anh, N.H.; Kim, S.W.; Park, S.; Kwon, S.W.; Lee, S.J. Effects of Oats (Avena sativa L.) on Inflammation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 722866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenzel, U.O.; Ehmke, H.; Bode, M. Immune mechanisms in arterial hypertension. Recent advances. Cell Tissue Res. 2021, 385, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, D.L.; Evans, M.A.; Chan, W.; Nawaz, H.; Comerford, B.P.; Hoxley, M.L.; Njike, V.Y.; Sarrel, P.M. Oats, Antioxidants and Endothelial Function in Overweight, Dyslipidemic Adults. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2004, 23, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, D.L.; Nawaz, H.; Boukhalil, J.; Chan, W.; Ahmadi, R.; Giannamore, V.; Sarrel, P.M. Effects of Oat and Wheat Cereals on Endothelial Responses. Prev. Med. 2001, 33, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.L.; Nawaz, H.; Boukhalil, J.; Giannamore, V.; Chan, W.; Ahmadi, R.; Sarrel, P.M. Acute effects of oats and vitamin E on endothelial responses to ingested fat. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2001, 20, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabesh, F.; Sanei, H.; Jahangiri, M.; Momenizadeh, A.; Tabesh, E.; Pourmohammadi, K.; Sadeghi, M. The Effects of Beta-Glucan Rich Oat Bread on Serum Nitric Oxide and Vascular Endothelial Function in Patients with Hypercholesterolemia. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 481904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.O.; Milbury, P.E.; Collins, F.W.; Blumberg, J.B. Avenanthramides Are Bioavailable and Have Antioxidant Activity in Humans after Acute Consumption of an Enriched Mixture from Oats. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 1375–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, S.; Yerke, A.; Ohland, C.L.; Gharaibeh, R.Z.; Fouladi, F.; Fodor, A.A.; Jobin, C.; Sang, S. Avenanthramide Metabotype from Whole-Grain Oat Intake is Influenced by Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in Healthy Adults. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 1426–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schär, M.Y.; Corona, G.; Soycan, G.; Dine, C.; Kristek, A.; Alsharif, S.N.S.; Behrends, V.; Lovegrove, A.; Shewry, P.R.; Spencer, J.P.E. Excretion of Avenanthramides, Phenolic Acids and their Major Metabolites Following Intake of Oat Bran. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, 1700499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Shao, J.; Gao, Y.; Chen, C.; Yao, D.; Chu, Y.F.; Johnson, J.; Kang, C.; Yeo, D.; Ji, L.L. Absorption and Elimination of Oat Avenanthramides in Humans after Acute Consumption of Oat Cookies. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 2056705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pridal, A.A.; Böttger, W.; Ross, A.B. Analysis of avenanthramides in oat products and estimation of avenanthramide intake in humans. Food Chem. 2018, 253, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Gong, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Sun, B. The Progress of Nomenclature, Structure, Metabolism, and Bioactivities of Oat Novel Phytochemical: Avenanthramides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, F.; Zhang, B.; Fan, J. In vitro inhibition of platelet aggregation by peptides derived from oat (Avena sativa L.), highland barley (Hordeum vulgare Linn. var. nudum Hook. f.), and buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) proteins. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; You, H.; Yu, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Ding, L. Identification and Characterization of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-IV Inhibitory Peptides from Oat Proteins. Foods 2022, 11, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandi, R.; Willmore, W.G.; Tsopmo, A. Peptidomic analysis of hydrolyzed oat bran proteins, and their in vitro antioxidant and metal chelating properties. Food Chem. 2019, 279, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandi, R.; Seidu, I.; Willmore, W.; Tsopmo, A. Antioxidant, pancreatic lipase, and α-amylase inhibitory properties of oat bran hydrolyzed proteins and peptides. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e13762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Velázquez, O.A.; Cuevas-Rodríguez, E.O.; Mondor, M.; Ribéreau, S.; Arcand, Y.; Mackie, A.; Hernández-Álvarez, A.J. Impact of in vitro gastrointestinal digestion on peptide profile and bioactivity of cooked and non-cooked oat protein concentrates. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleakley, S.; Hayes, M.; Shea, N.O.; Gallagher, E.; Lafarga, T. Predicted Release and Analysis of Novel ACE-I, Renin, and DPP-IV Inhibitory Peptides from Common Oat (Avena sativa) Protein Hydrolysates Using in Silico Analysis. Foods 2017, 6, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhuang, Y.; Li, Y.; Shi, P.; Tian, H.; Li, X.; Chen, X. Isolation of novel ACE-inhibitory peptide from naked oat globulin hydrolysates in silico approach: Molecular docking, in vivo antihypertension and effects on renin and intracellular endothelin-1. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 1328–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, I.W.Y.; Nakayama, S.; Hsu, M.N.K.; Samaranayaka, A.G.P.; Li-Chan, E.C.Y. Angiotensin-I Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Activity of Hydrolysates from Oat (Avena sativa) Proteins by In Silico and In Vitro Analyses. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 9234–9242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oketch-Rabah, H.A.; Madden, E.F.; Roe, A.L.; Betz, J.M. United States Pharmacopeia (USP) Safety Review of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA). Nutrients 2021, 13, 2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, D.-H.; Vo, T.S. An Updated Review on Pharmaceutical Properties of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid. Molecules 2019, 24, 2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.G.; Tian, C.R.; Hu, Q.P.; Luo, J.Y.; Wang, X.D.; Tian, X.D. Dynamic Changes in Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Oats (Avena nuda L.) during Steeping and Germination. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 10392–10398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Ashraf, U.; Zhong, D.; Lin, R.; Xian, P.; Zhao, T.; Feng, H.; Wang, S.; Duan, M.; Tang, X.; et al. Application of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and nitrogen regulates aroma biochemistry in fragrant rice. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 3784–3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Sang, S. Triterpenoid Saponins in Oat Bran and Their Levels in Commercial Oat Products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 6381–6389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Tang, Y.; Snooks, H.D.; Sang, S. Novel Steroidal Saponins in Oat Identified by Molecular Networking Analysis and Their Levels in Commercial Oat Products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 7084–7092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, P.; Wu, W.; Zhao, Y.; Idehen, E.; Sang, S. Steroidal Saponins in Oat Bran. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrelli, M.; Conforti, F.; Araniti, F.; Statti, G.A. Effects of Saponins on Lipid Metabolism: A Review of Potential Health Benefits in the Treatment of Obesity. Molecules 2016, 21, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Long, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Pian, H.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z. Protective effects of saponin on a hypertension target organ in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Exp. Ther. Med. 2013, 5, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Guan, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhai, F.; Zhang, X.; Guan, L. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells by which Total Saponin Extracted from Tribulus Terrestris Protects Against Artherosclerosis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 32, 1299–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Citation | Purpose/Description | Conclusions on Oats |

|---|---|---|

| Evans et al. [8] | Assessed the effect of different types of fibers on BP. RCTs of at least 6 wks duration, testing a fiber isolate or fiber-rich diet against a control or placebo. Included 5 and 4 studies on oat β-glucan rich interventions for SBP and DBP analyses, respectively, published between 1 January 1990 and 1 December 2013. | SBP: Combined fiber interventions resulted in a significant (p = 0.023) decrease of −0.92 (95% CI: −2.48, 0.63). The subgroup analysis of oats or β-glucan-rich intervention showed a decrease of −2.69 (95% CI: −4.6, −0.73). DBP: Combined fiber interventions resulted in a significant (p = 0.001) decrease of −0.71 (95% CI: −1.90, 0.47). The subgroup analysis of oats or β-glucan-rich intervention showed a decrease of −1.45 (95% CI: −2.68, −0.22). Higher consumption of β-glucan fiber is associated with both lower SBP and DBP, with a median difference of 4 g. Data suggests much of the effect of fiber on BP may be driven by β-glucan-rich fiber sources. |

| Llanaj et al. [24] | Assess the effects of oat supplementation interventions on CVD risk factors. RCTs that included oat, oat β-glucan-rich extracts, and avenanthramides on CVD risk markers (e.g., blood lipids, glucose, BP). Included 5 studies comparing oats vs. diet or no-oats control, 5 studies comparing dietary restriction with and without oats, and 7 studies of oats vs. a heterogeneous control, published from database inception until 15 May 2020. | SBP: Decreased non-significantly (WMD, −0.56 mmHg; 95% CI −1.68 to 0.56; p = 0.20; I2 = 33.8) when oats compared to similar diet or product intervention, and a slight significant increase for oats with restrictive diet compared to diet alone (WMD, 0.170 mmHg, 95% CI −2.168 to 2.508; p < 0.001; I2 = 88.3) or comparison to heterogeneous (e.g., wheat, fiber, rice, eggs, etc.) interventions (WMD, 0.547 mmHg; 95% CI −0.564 to 1.657, p < 0.001; I2 = 85.3). DBP: Decreased non-significantly (WMD, −0.69 mmHg, 95% CI −1.59 to 0.22; p = 0.14; I2 = 42.8) when oats compared to similar diet or product intervention and for oats with restrictive diet compared to diet alone (WMD, −1.154 mmHg, 95% CI −2.030 to −0.0278; p = 0.060; I2 = 55.9), and significant slight increase for comparison to heterogeneous (e.g., wheat, fiber, rice, eggs, etc.) interventions (WMD, 0.357 mmHg; 95%CI −1.210 to 1.925; p < 0.001; I2 = 96.8). The effect of oat supplementation on BP was inconsistent, similar to that observed for glucose, and further high-quality trials are warranted. |

| Khan et al. [25] | Investigate the effects of viscous soluble fiber supplementation on BP and quantify the effects of individual fibers. Studies that assessed interventions of viscous soluble fiber supplements or diets enriched with soluble fiber on BP outcomes with durations of at least 4 wks. Included 8 studies on oat-soluble fiber published through 10 June 2017. | SBP: Assessment of the combined viscous fibers results in a significant reduction (MD, −1.59; 95% CI, −2.72, −0.46; p < 0.01), with subgroup analysis for β-glucan showing a similar decrease, although not significant (−1.50; 95% CI, −3.16, 0.16; p = 0.08). DBP: Assessment of the combined viscous fibers results in a modest reduction (MD, −0.39; 95% CI, −0.76, −0.0; =0.05), with subgroup analysis for β-glucan showing a greater decrease (−1.02; 95% CI, −2.06, 0.01; p = 0.05). |

| Reynolds et al. [28] | Examine the evidence for diets high in fiber on the management of CVD or HTN. Controlled trials of at least 6 wks duration of increasing fiber intakes in subjects with CVD or HTN and reporting on cardiometabolic risk factors. Nine studies assessed fiber in subjects with HTN for the systematic review and eight studies were used in the meta-analysis. Four studies used oats as the fiber source. | SBP: Decreased for fiber (MD, −4.3 mmHg, 95% CI −5.8 to −2.8) for combined fiber types, with studies assessing oats contributing ~34.3% of weighted contribution. DBP: Decreased for fiber (MD, −3.1 mmHg, 95% CI −4.4 to −1.7) for combined fiber types, with studies assessing oats contributing ~34.2% of weighted contribution. The effect of oat supplementation on BP was not assessed separately. |

| Citation (Δ) | Location | Subject Characteristics * | Trial Design/ Duration § | Oat Intervention | Control/ Comparator | BP Change mmHg (95% CI) † |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saltzman et al. [14] (1, 2, 3) | USA | Generally healthy N = 43: 49% male, Age: 20–70 y BMI: 20–35 kg/m2 SBP: 118 (15) mmHg DBP: 70 (8) mmHg Stratified on age (18–30 y; 60–75 y), sex, and BMI | BP co-primary parallel 6 wk 2 arms | 45 g/1000 kcal of rolled oats (~3.7 g/d fiber) total fiber = 16 g/d (7.2 g soluble fiber) | 45 g/1000 kcal of wheat products total fiber = 12.5 g/d (3.5 g soluble fiber) | SBP: WMD, −5.00 (−9.25, −0.75) DBP: WMD, −1.00 (−8.68, 6.68) Oat: ‡ SBP: 120 (110–130) mmHg to 110 (100–120) mmHg (p < 0.05) DBP: 80 (70–90) mmHg to 70 (70–80) mmHg (p < 0.05) Wheat: ‡ SBP: 120 (115–130) mmHg to 110 (105–120) mmHg (p < 0.05) DBP: 80 (80–85) mmHg to 70 (70–80) mmHg (p < 0.05) Δwt = NR |

| Wolever et al. [20] | Canada | Hypercholesterolemic N = 191: 37.7% Male Age: 47.6 (11.4) y BMI: 27.9 (4.6) kg/m2 SBP: 121 (13) mmHg DBP: 76 (9) mmHg | BP secondary parallel randomized double-blind 4 wk 2 arm | 1 g oat β-glucan (produced by treating an oat product enzymatically to reduce starch content without affecting MW of β-glucan) | Rice milk powder | Oat β-glucan: ‡ SBP: 120 (1) mmHg to 121 (1) mmHg (ns) DBP: 75 (1) mmHg to 76 (1) mmHg (ns) Control: ‡ SBP: 119 (2) mmHg to 120 (1) mmHg (ns) DBP: 76 (1) mmHg to 77 (1) mmHg (ns) Δwt = ns |

| Pins et al. [29] (2, 3, 4) | USA | HTN subjects N = 88: ~50% Male Age: 30–66 y BMI: 30.6–31.2 kg/m2 SBP: 139 (16) mmHg DBP: 87 (10) mmHg Stratified by baseline SBP and soluble fiber | BP Co-primary parallel randomized single-blind 12 wk 2 arms >6 wk follow-up | 60 g/d oatmeal (5.61 g/d dietary fiber, 3.25 g/d soluble fiber, 3.25 g/d β-glucan) + 77 g/d oat squares (6.07 g/d dietary fiber, 2.98 g/d soluble fiber, 2.59 g/d β-glucan) | 65 g/d hot wheat cereal (2.32 g/d dietary fiber, 0.6 g/d soluble fiber) + 81 g/d corn and rice RTE cereal (1.2 g/d dietary fiber, <0.5 g/d soluble fiber) | SBP: WMD, −6.00 (−11.80, −0.20) DBP: WMD −5.00 (−12.17, 2.17) Anti-HTN medication ≥50% decreased or discontinued by 73% vs. 42% (p < 0.05) in oat vs. control groups, respectively. During post-study follow-up, 67% vs. 33% (p < 0.05) resumed medications in oat vs. control groups, respectively. Changes in those without medication: ‡ ΔSBP: oat, −7 (8) mmHg; control −1 (9) mmHg; p < 0.05 ΔDBP: oat, −4 (5) mmHg; control, +1 (6); p = 0.18 Δwt: ns |

| He et al. [30] (1, 2, 3, 4) | USA | HTN subjects N = 110: 40% male, Age: 37–60 y BMI: 23–34 kg/m2 SBP: 116–140 mmHg DBP: 73–85 mmHg %HTN: ~15% | BP primary parallel double-blind 12 wk 2 arms | 60 g/d OB in muffins and 84 g/d oatmeal cereal squares delivering 7.3 g/d β-glucan. Total fiber: ~15.9 g/d (7.3 g as β-glucan) | 93 g refined wheat in muffins and 42 g cornflake cereal. Fiber: 2.7 g/d (no β-glucan) | SBP: WMD, −1.8 (−4.3, 0.8; p = 0.17) DBP: WMD −1.2 (−3.0, 0.5; p = 0.17) After adjustment of the mean difference (95% CI) for age, race, sex, baseline BP, fiber, and wt, a change in wt resulted in a reduced net change for SBP of −0.5 mmHg (−2.7, +1.7; p = 0.64) and DBP of −1.0 mmHg (−2.0, +0.6; p = 0.24) Within-group analysis suggested a significant decrease in the high-fiber group for SBP (−3.4 mmHg; 95%CI, −5.2, +1.7; p < 0.001) and DBP (−2.1; 95%CI, 3.1, +1.0; p < 0.001) for the high-fiber group, and a non-significant change for SBP (−1.4 mmHg; 95%CI, −3.0, +0.2; p = 0.08) and DBP (−1.1 mmHg; 95%CI, −2.2, +0.1; p = 0.07) for the low-fiber group Δwt (kg) = 0.1 kg on oat intervention, 0.7 kg on control, p = 0.07 for difference |

| Xue et al. [31] (4) | China | HTN subjects N = 50: 72.7% Males Age: 47 (13) y BMI: 24.9 (2.5) kg/m2 SBP: 140–159 mmHg DBP: 90–99 mmHg 31.8% on anti-HTN medications | BP co-primary randomized 3 mo 2 arms 1 wk run-in | Arm 1: 30 g/d OB DASH diet guidance | Arm 2: DASH diet guidance | Office BP measurements for oats: ‡ SBP: 138.0 (11.1) mmHg to 122.6 (8.8) mmHg DBP: 91.7 (11) mmHg to 81.5 (7.7) mmHg Office BP measurements for control: ‡ SBP: 137.2 (10.1) mmHg to 133.0 (7.4) mmHg DBP: 86.8 (9.9) mmHg to 87.4 (9.2) mmHg Between-group mean differences for SBP and DBP were ns at baseline and significant (p < 0.001, p = 0.00) at end of the study, respectively. No significant differences in 24 min SBP or 24 min DBP. Significant mean differences for 24 h max and 24 h average SBP and DBP. Anti-HTN medications: control, 9.1% increased, oat, 0% increased, 31.8% decreased or discontinued (p = 0.021) Δwt = NR |

| Charlton et al. [33] (1, 2) | AUS | Dyslipidemic subjects N = 90: 48% Male, Age: 49.75–52.43 y BMI: 27.74–26.74 kg/m2 SBP: 132.12–128.76 mmHg DBP: 78.21–76.39 mmHg | BP secondary parallel randomized single-blind 6 wk 3 arms | Arm 1: High oats (3.24 g/d β-glucan) Arm 2: Low oats (1.45 g/d β-glucan) RTE oat flakes, oat cereal bars, oat porridge LFaD | Arm 3: Control (0 g/d β-glucan) RTE cornflakes, puffed rice bars LFaD | SBP (combined): WMD, 0.30 (−8.19, 8.79) SBP Mean change (mmHg) over 6 wk: Arm 1, −5.6; Arm 2, −4.7, Arm 3, −8.9; ns DBP: NR Δwt (kg): =0.7 kg |

| Davy et al. [34] (1, 2, 3) | USA | HTN subjects N = 36: 100% Male, Age: 57–61 y BMI: 29–30 kg/m2 SBP:133.7–138.2 mmHg, DBP: 88.1–88.5 mmHg, Fiber: 17–23 g/d | BP primary parallel randomized 12 wk 2 arms | 60 g oatmeal and 76 g OB RTE cold cereal Dietary fiber: 14 g/d β-glucan: 5.5 g/d | Wheat-based RTE cold cereal control, Dietary fiber: 14 g/d β-glucan: 0 g/d | SBP: WMD, −5.70 (−13.51, 2.11) DBP: WMD, −3.30 (−4.34, 2.32) No significant difference for SBP or DBP in daytime casual and supine arterial, 24-ambulatory, variability, nocturnal dip, load, or pulse rate. For SBP, no differences in nighttime or MAP, but a small, significant, increase in nighttime DBP and MAP in both placebo and β-glucan. Δwt (kg): 0.2 |

| Liao et al. [35] (3) | Taiwan | Mild hypercholesterolemic N = 48 hypercholesterolemic and N = 34 normal: Age: 38–76 y BMI: 23.38–23.66 kg/m2 SBP: 116.95–126.23 mmHg DBP: 77.73–78.91 mmHg | BP secondary parallel randomized double-blind 10 wk 2 arms | 100 g/d (366 kcal) Oat noodles (80% oat, 3.12 g/d β-glucan, 20% wheat flour) | 100 g/d (190 kcal) Wheat noodles (100% wheat flour) | Oat noodles: ‡ SBP: 126.23 (3.81) to 112.38 (4.12) mmHg (p < 0.01) DBP: 78.91 (1.89) to 73.00 (2.31) mmHg (p < 0.05) Wheat noodles: ‡ SBP: 116.95 (2.42) to 119.50 (3.03) mmHg (ns) DBP: 77.73 (2.07) to 73.33 (1.76) mmHg (ns) Δwt: No change for both groups (range 58.66 kg to 58.11 kg) |

| Maki et al. [36] (1, 4 SR only) | USA | Elevated SBP and/or DBP N = 97: 55% Male Age: 56–62 y BMI: 32.2–32.6 kg/m2 SBP: 138.9, 139.9 mmHg DBP: 82.8, 83.9 mmHg Fiber < 20 g/d | BP primary parallel randomized double-blind 12 wk 2 arms | 90 g/d OB cereal + 60 g/d oatmeal + 20 g/d powdered oat β-glucan Total dietary fiber: 17.3 g/d (7.7 g/d β-glucan) | 90 g/d Low-fiber RTE (wheat) cereal + 65 g/d Low fiber hot cereal + 12 g/d placebo supplement Total dietary fiber: 1.9 g/d fiber (no β-glucan) | SBP: WMD, −3.80 (−8.78, 1.18) High-BMI (>31.5 kg/m2) subgroup analysis: significant between-group difference for ΔSBP (oat, −5.6 mmHg; control, +2.7 mmHg; p = 0.008) and ΔDBP (oat, −2.1 mmHg; control, +1.9 mmHg; p = 0.018) No between-group significant differences for SBP or DBP overall, or for the lower-BMI subgroup analyses Δwt: <1 kg for both groups, ns |

| Onning et al. [37] (2, 3) | Sweden | Dyslipidemic subjects N = 52: 100% males Age: BMI: kg/m2 | Crossover, double-blind 5 wk | Oats delivering 3.8 g/d β-glucan | Rice | SBP: WMD, −1.60 (−5.50, 2.30) DBP: WMD −1.50 (−2.44, −0.56) Δwt = +1%, p < 0.001 |

| Queenan et al. [38] (2, 3) | USA | Dyslipidemic subjects N = 75: 33% males Age = ~45 y BMI = NR SBP: 121 mmHg DBP: 67–69 mmHg | BP secondary parallel randomized double-blind 6 wk 2 arms | 6.0 g/d concentrated oat β-glucan supplement (from 12 g OB concentrate) | 6 g/d placebo (dextrose) supplement | SBP: WMD, 0.00 (−0.10, 0.10) DBP: WMD 0.00 (−0.12, 0.12) Oat β-glucan: ‡ SBP: 121 (2.2) mmHg to 119 (1.9) (ns) DBP: 69 (1.4) mmHg to 69 (1.3) mmHg (ns) Placebo: ‡ SBP: 121.6 (1.9) mmHg to 119 (2.0) mmHg (ns) DBP: 67.1 (1.5) mmHg to 69 (1.7) mmHg (ns) No significant difference between groups at end of the intervention Δwt: placebo, 1.4 (1.3) kg, oat, −0.7 (0.3), ns |

| Momenizadeh et al. [39] (3) | Iran | Hypercholesterolemia N = 60: 35% Males Age: 51.12 (9.31) y BMI: 28.94–28.99 kg/m2 SBP: 114.83–115.17 mmHg DBP: 76.33–77.00 mmHg | BP secondary parallel randomized 6 wk 2 arms LED 2 wk run-in | 150 g/d OB bread (30 g/d β-glucan) + LED | 150 g/d wheat bread (no β-glucan) + LED | oat: ‡ SBP: 114.83 (10.95) mmHg to 112.50 (12.16) mmHg (ns) DBP: 77.00 (9.15) mmHg to 76.33 (8.90) mmHg Control: ‡ SBP: 115. 17 (14.65) mmHg to 114.83 mmHg (13.55), ns DBP: 76.33 (10.74) mmHg to 75.33 (9.37) mmHg No significant difference in SBP or DBP between groups |

| Raimondi de Souza et al. [40] (3) | Brazil | Hypercholesterolemia N = 132: 33% Male Age: 40–70 y (~30% <60 y) BMI: 25–35 kg/m2 SBP: 120 mmHg DBP: 80 mmHg Fiber: 21.7–22.3 g/d | BP secondary randomized double-blind 90 d 2 arms | 40 g OB (β-glucans) in fat-free powdered milk + nutrition counseling | Placebo: 40 g corn starch and rice flour + nutrition counseling | Oat β-glucan: SBP: 120 (110–130) mmHg to 110 (100–120) mmHg (p < 0.05) DBP: 80 (70–90) mmHg to 70 (70–80) mmHg (p < 0.05) Placebo: SBP: 120 (115–130) mmHg to 110 (105–120) mmHg (p < 0.05) DBP: 80 (80–85) mmHg to 70 (70–80) mmHg (np < 0.05) No significant difference in BP between groups. Δwt = oat, −3.5 kg (p < 0.05); placebo, −2.0 kg (p < 0.05) |

| Swain et al. [41] (1, SR only) | USA | Hypercholesterolemia N = 20: 20% males, Age: 30 (23–49) y BMI: NR SBP: 112 mmHg DBP: 68 mmHg | BP secondary crossover randomized double-blind 6 wk 2 arms | High-fiber: 100 g OB in muffins and entrees (21 g/d fiber) Total dietary fiber: 38.9 g/d | Low-fiber: 100 g refined wheat in muffins and entrees Total dietary fiber: 18.4 g/d | No significant change in BP in either group. During high fiber: SBP: 110 mmHg; DBP: 67 mmHg During low fiber: SBP: 107 mmHg; DBP: 65 mmHg Δwt = −0.1, ns |

| Zhang et al. [42] (2, 3) | China | Hypercholesterolemic N = 166: 39% males Age: 52.7, 53.7 y BMI: 25.5 (0.33) kg/m2 SBP: 124.7, 129 mmHg DBP: 80.3, 79.7 mmHg | BP secondary parallel randomized Single-blind 6 wk 2 arms | 100 g/d instant oatmeal (~3.6 g/d soluble fiber) Total dietary fiber: 19.3 g/d | 100 g/d wheat flour-based noodles Total dietary fiber: 12.9 g/d | SBP: WMD, 0.16 (−2.92, 3.24) DBP: WMD, −0.89 (−3.48, 1.70) Oat: ‡ SBP: 124.7 (1.74) mmHg to 125.7 (1.65) mmHg DBP: 80.3 (1.06) mmHg to 80.1 (0.97) mmHg Control: ‡ SBP: 129.0 (1.78) mmHg to 129.9 (1.69) mmHg DBP: 79.7 (1.09) mmHg to 80.4 (1.00) mmHg No significant difference between groups Δwt = −0.46 kg, +0.67 kg; ns |

| AlFaris and Ba-Jaber [43] | Saudi Arabia | Type 2 diabetics N = 78: 0% Male Age: 25–60 y BMI: 29.3–36.7 kg/m2 SBP: 113.1–132.7 m Hg DBP: 78.5–85.8 mmHg | BP co-primary parallel randomized 3 mo 6 arms Stratified by TG and BMI | Arm 3: 10 g/d OB Arm 4: 10 g/d OB + 5 g/d OO Arm 5: 10 g/d OB Arm 6: 10 g/d OB + 5 g/d OO Included LED + education + meal plans | Arm 1: no intervention Arm 2: LED + education + meal plans | OB + LED results compared to Arm 1: ‡ SBP: High TG, −4.6 (12.0, −3.7; ns) High BMI: −11.9 (12.5, −9.0; p < 0.05) DBP: High TG, −3.8 (8.7, −4.8; ns) High BMI: −10.8 (7.6, −12.6; p < 0.05) Arm 1 vs. Arm 2 comparisons: ‡ SBP: −1.2 (15.3, −1.0; ns) DBP: −7.7 (7.0, −9.1; p < 0.05) |

| Cicero et al. [44] | Italy | Dyslipidemic subjects N = 83: 42% Male Age: 52.3 (4.4) y wt: 74.5 (17.4) kg Waist: 91.3 (14.6) cm SBP: 128.3 (15.3) mmHg DBP: 81 (9.6) mmHg Fiber: 2.2 (0.9) %en | BP secondary crossover randomized double-blind 8 wk 2 arms | 3 g oat β-glucan 10 g sachet | Placebo Oat-based isocaloric 10 g sachet with no β-glucan | Mean changes: SBP: Placebo: −0.6 (−5.4, 4.2; ns) β-glucan: −4.8 (−9.7, 0.1; p = 0.053) DBP: Placebo: 0.7 (−2.1, 3.6; ns) β-glucan: −1 (−3.9, 1.9; ns) Δwt (kg): Placebo:‡ −0.2 (−5.4, 5.1; ns) β-glucan: ‡ −0.5 (−6.1, 5.0; ns) |

| de Souza Leão et al. [45] | Brazil | Metabolic syndrome subjects N = 154: NR % Male Age: 47.6 (12.5) y BMI: 33.9–35 kg/m2 SBP: 135.1–135.7 mmHg DBP: 87.3–88.8 mmHg | BP co-primary parallel randomized open-label 6 wk | 40 g/d OB (3 g/d β-glucan) + LED | LED | Control: ‡ %HTN from 87.3% to 54.7% (ns) SBP: 136.2 (18.1) to 124.1 (13.7) mmHg (p < 0.001) DBP: 87.6 (14) to 80.7 (10.5) mmHg, p = 0.002 OB: ‡ %HTN: from 84.3% to 51.9% (ns) SBP: 135.4 (16.9) to 124.6 (17.1) mmHg (p < 0.001) DBP: 89.1 to 80.8 (11.4) mmHg (p < 0.001) ΔSBP: Control, −12.1; OB, −10.8 (ns) ΔDBP: Control, −6.9; OB, −8.2 (ns) ΔBMI = significant, similar decrease (1.3 kg/m2) in both arms (difference ns) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liska, D.J.; Dioum, E.; Chu, Y.; Mah, E. Narrative Review on the Effects of Oat and Sprouted Oat Components on Blood Pressure. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4772. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14224772

Liska DJ, Dioum E, Chu Y, Mah E. Narrative Review on the Effects of Oat and Sprouted Oat Components on Blood Pressure. Nutrients. 2022; 14(22):4772. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14224772

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiska, DeAnn J., ElHadji Dioum, Yifang Chu, and Eunice Mah. 2022. "Narrative Review on the Effects of Oat and Sprouted Oat Components on Blood Pressure" Nutrients 14, no. 22: 4772. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14224772

APA StyleLiska, D. J., Dioum, E., Chu, Y., & Mah, E. (2022). Narrative Review on the Effects of Oat and Sprouted Oat Components on Blood Pressure. Nutrients, 14(22), 4772. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14224772