The Impact of School-Based Nutrition Interventions on Parents and Other Family Members: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.3. Quality Assessment

3. Results

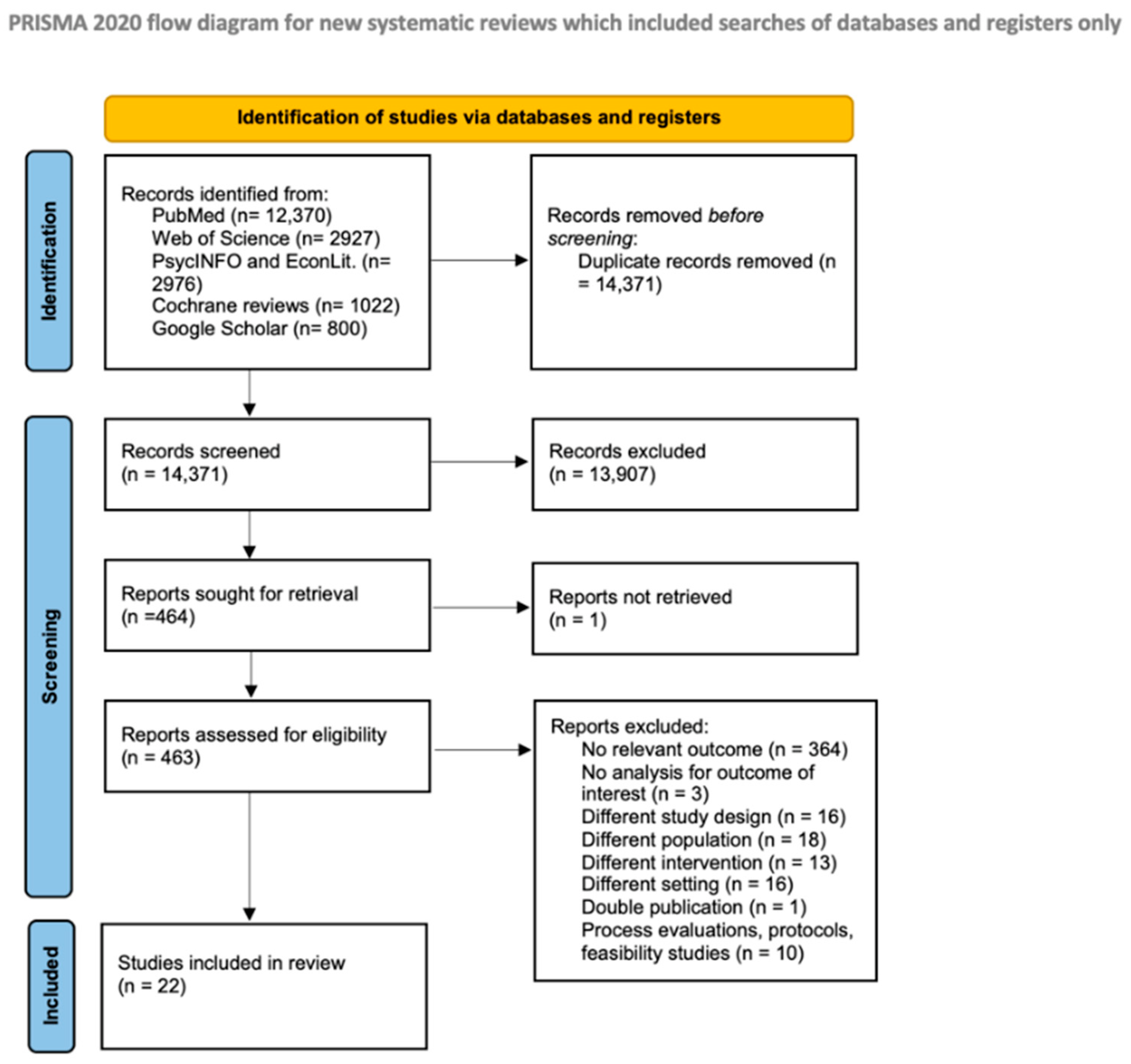

3.1. Literature Search Results

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Countries and Study Design

3.4. Participant Characteristics

3.5. Intervention Characteristics

3.6. Quality Assessment

3.7. Parental/Family Outcomes

3.7.1. Dietary Intake

3.7.2. Nutrition Knowledge

3.7.3. Health Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases, Fact Sheets 2021; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Afshin, A.; Sur, P.J.; Fay, K.A.; Cornaby, L.; Ferrara, G.; Salama, J.S.; Mullany, E.C.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abebe, Z.; et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriti, M.; Varoni, E.M.; Vitalini, S. Healthy Diets and Modifiable Risk Factors for Non-Communicable Diseases-The European Perspective. Foods 2020, 9, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Daniele, N. The Role of Preventive Nutrition in Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraf, D.S.; Nongkynrih, B.; Pandav, C.S.; Gupta, S.K.; Shah, B.; Kapoor, S.K.; Krishnan, A. A systematic review of school-based interventions to prevent risk factors associated with noncommunicable diseases. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2012, 24, 733–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akseer, N.; Mehta, S.; Wigle, J.; Chera, R.; Brickman, Z.J.; Al-Gashm, S.; Sorichetti, B.; Vandermorris, A.; Hipgrave, D.B.; Schwalbe, N.; et al. Non-communicable diseases among adolescents: Current status, determinants, interventions and policies. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilly, J.J.; Kelly, J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: Systematic review. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvan, M.S.; Kurpad, A.V. Primary prevention: Why focus on children & young adolescents? Indian J. Med. Res. 2004, 120, 511–518. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Standards for Health Promoting Schools; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Silveira, J.A.; Taddei, J.A.; Guerra, P.H.; Nobre, M.R. Effectiveness of school-based nutrition education interventions to prevent and reduce excessive weight gain in children and adolescents: A systematic review. J. Pediatr. 2011, 87, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, C.M.; Hardy-Johnson, P.L.; Inskip, H.M.; Morris, T.; Parsons, C.M.; Barrett, M.; Hanson, M.; Woods-Townsend, K.; Baird, J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based interventions with health education to reduce body mass index in adolescents aged 10 to 19 years. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verjans-Janssen, S.R.B.; van de Kolk, I.; Van Kann, D.H.H.; Kremers, S.P.J.; Gerards, S. Effectiveness of school-based physical activity and nutrition interventions with direct parental involvement on children’s BMI and energy balance-related behaviors—A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, C.C.; Flanders, S.A.; Bader, S.G. Can Children Reduce Delayed Hospital Arrival for Ischemic Stroke?: A Systematic Review of School-Based Stroke Education. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2016, 48, e2–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berniell, L.; de la Mata, D.; Valdés, N. Spillovers of health education at school on parents’ physical activity. Health Econ. 2013, 22, 1004–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Effective Public Health Practice Project. Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. Available online: http://www.ephpp.ca/tools.html (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Dong, J.; Gao, C.C.; Xu, C.X.; Tang, J.L.; Ren, J.; Zhang, J.Y.; Chen, X.; Shi, W.H.; Zhao, Y.F.; Guo, X.L.; et al. Evaluation on the effect of salt reduction intervention among fourth-grade primary school students and their parents in Shandong Province. Chin. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 53, 519–522. [Google Scholar]

- He, F.J.; Ma, Y.; Feng, X.; Zhang, W.; Lin, L.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Noi, W.; Wu, Y.; MacGregor, G.A. Effect of salt reduction on iodine status assessed by 24 hour urinary iodine excretion in children and their families in northern China: A substudy of a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.J.; Wu, Y.; Feng, X.X.; Ma, J.; Ma, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, J.; Lin, C.P.; Nowson, C.; et al. School based education programme to reduce salt intake in children and their families (School-EduSalt): Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2015, 350, h770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, N.I.; Te Velde, S.J.; Brug, J. Long-term effects of the Dutch Schoolgruiten Project—Promoting fruit and vegetable consumption among primary-school children. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 1213–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, N.I.; Te Velde, S.J.; Brug, J. Ethnic differences in 1-year follow-up effect of the Dutch Schoolgruiten Project—Promoting fruit and vegetable consumption among primary-school children. Public Health Nutr. 2007, 10, 1497–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bjelland, M.; Hausken, S.E.S.; Bergh, I.H.; Grydeland, M.; Klepp, K.-I.; Andersen, L.F.; Totland, T.H.; Lien, N. Changes in adolescents’ and parents’ intakes of sugar-sweetened beverages, fruit and vegetables after 20 months: Results from the HEIA study—A comprehensive, multi-component school-based randomized trial. Food Nutr. Res. 2015, 59, 25932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom-Hoffman, J.; Wilcox, K.R.; Dunn, L.; Leff, S.S.; Power, T.J. Family Involvement in School-Based Health Promotion: Bringing Nutrition Information Home. Sch. Psych. Rev. 2008, 37, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess-Champoux, T.L.; Chan, H.W.; Rosen, R.; Marquart, L.; Reicks, M. Healthy whole-grain choices for children and parents: A multi-component school-based pilot intervention. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 11, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crockett, S.J.; Mullis, R.; Perry, C.L.; Luepker, R.V. Parent education in youth-directed nutrition interventions. Prev. Med. 1989, 18, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gewa, C.A.; Murphy, S.P.; Weiss, R.E.; Neumann, C.G. A school-based supplementary food programme in rural Kenya did not reduce children’s intake at home. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Gunawardena, N.; Kurotani, K.; Indrawansa, S.; Nonaka, D.; Mizoue, T.; Samarasinghe, D. School-based intervention to enable school children to act as change agents on weight, physical activity and diet of their mothers: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, D.L.; Katz, C.S.; Treu, J.A.; Reynolds, J.; Njike, V.; Walker, J.; Smith, E.; Michael, J. Teaching healthful food choices to elementary school students and their parents: The Nutrition DetectivesTM program. J. Sch. Health 2011, 81, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, J.; Grantham-McGregor, S.; Ismail, S.; Ashley, D. A child-to-child programme in rural Jamaica. Child Care Health Dev. 1991, 17, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, S.A.; Huddy, A.D.; Adams, J.K.; Miller, M.; Holden, L.; Dietrich, U.C. The tooty fruity vegie project: Changing knowledge and attitudes about fruits and vegetables. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2004, 28, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øvrum, A.; Bere, E. Evaluating free school fruit: Results from a natural experiment in Norway with representative data. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1224–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, C.L.; Bishop, D.B.; Taylor, G.; Murray, D.M.; Mays, R.W.; Dudovitz, B.S.; Smyth, M.; Story, M. Changing fruit and vegetable consumption among children: The 5-a-Day Power Plus program in St. Paul, Minnesota. Am. J. Public Health 1998, 88, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, K.D.; Franklin, F.A.; Binkley, D.; Raczynski, J.M.; Harrington, K.F.; Kirk, K.A.; Person, S. Increasing the fruit and vegetable consumption of fourth-graders: Results from the high 5 project. Prev. Med. 2000, 30, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.V.; Markham, C.; Chow, J.; Ranjit, N.; Pomeroy, M.; Raber, M. Evaluating a school-based fruit and vegetable co-op in low-income children: A quasi-experimental study. Prev. Med. 2016, 91, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi-Chang, X.; Xin-Wei, Z.; Shui-Yang, X.; Shu-Ming, T.; Sen-Hai, Y.; Aldinger, C.; Glasauer, P. Creating health-promoting schools in China with a focus on nutrition. Health Promot. Int. 2004, 19, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Te Velde, S.J.; Wind, M.; Perez-Rodrigo, C.; Klepp, K.I.; Brug, J. Mothers’ involvement in a school-based fruit and vegetable promotion intervention is associated with increased fruit and vegetable intakes—Tthe Pro Children study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Stewart, D.; Chang, C. School-based intervention for nutrition promotion in Mi Yun County, Beijing, China: Does a health-promoting school approach improve parents’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviour? Health Educ. 2016, 116, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhouse, L.; Bussell, P.; Jones, S.; Lloyd, H.; Macdowall, W.; Merritt, R. Bostin value: An intervention to increase fruit and vegetable consumption in a deprived neighborhood of dudley, United Kingdom. Soc. Mark. Q. 2012, 18, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005, 6th ed.; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- National Cancer Institute. 5 a Day for Better Health Program Guidebook; National Cancer Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1991.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010, 7th ed.; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 20 December 2010.

- Racey, M.; O’Brien, C.; Douglas, S.; Marquez, O.; Hendrie, G.; Newton, G. Systematic Review of School-Based Interventions to Modify Dietary Behavior: Does Intervention Intensity Impact Effectiveness? J. Sch. Health 2016, 86, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.E.; Christian, M.S.; Cleghorn, C.L.; Greenwood, D.C.; Cade, J.E. Systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based interventions to improve daily fruit and vegetable intake in children aged 5 to 12 y. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, K.M.; Hemingway, A.; Saulais, L.; Dinnella, C.; Monteleone, E.; Depezay, L.; Morizet, D.; Perez-Cueto, F.J.A.; Bevan, A.; Hartwell, H. Increasing vegetable intakes: Rationale and systematic review of published interventions. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 869–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzaffar, H.; DiFilippo, K.N.; Fitzgerald, N.; Tidwell, D.K.; Idris, R.; Kurzynske, J.S.; Chapman-Novakofski, K. A Systematic Review of Interventions to Improve Diet Quality of Children that Included Parents Versus Those Without Parental Involvement. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4 (Suppl. S2), 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lippevelde, W.; Verloigne, M.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Brug, J.; Bjelland, M.; Lien, N.; Maes, L. Does parental involvement make a difference in school-based nutrition and physical activity interventions? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Public Health 2012, 57, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors Year, Country | Design | Participants | Intervention | Theoretical Framework | Intervention Duration | Intervention Components | Parental/ Family Outcomes of Interest | Quality Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bjelland et al., 2015 [23], Norway | CRCT | Sixth-grade students: n = 1418; Mothers: n = 849; Fathers: n = 680 | Health In Adolescents | NR | 20 mo. | Classroom components, home/parents’ components, school wide components, and leisure time activities | Parental intakes of sugar-sweetened soft drinks and sugar- sweetened fruit drinks; Intake of FV | Weak |

| Blom-Hoffman et al., 2008 [24], USA | Non-RCT | Kindergarten and first-grade students: n = 297; Parents: n = 80 | Fruit and Vegetable Promotion Program | NR | 16 mo. | Morning announcements highlighting the FV of the day and an associated fact; posters; Dole CD-ROM during computer special or in the classroom; and assignments and take-home books | Parental knowledge of the “5 a Day” message | Weak |

| Burgess-Champoux et al., 2008 [25], USA | Non-RCT | Fourth- and fifth-grade students/ parent pairs: I: n = 67, C: n = 83 | The ‘Power of 3: Get Healthy with Whole Grain Foods’ | SCT | 5 mo. | Five-lesson classroom curriculum, school cafeteria menu modifications, and family involvement | Parental self-reported intake of refined- grain/whole grain foods | Moderate |

| Crockett et al., 1989 [26], USA | Non-RCT | Parents of third-grade students: n = 465 | Hearty Heart and Friends & Hearty Heart Home Team | SLT | 5 wk. | Hearty Heart and Friends: a third-grade curriculum; Hearty Heart Home Team: a five-week parent-taught intervention that is mailed to students’ homes; Hearty Heart and Home Team: both school and parent-taught; and Control group: no intervention | Parental knowledge about diet and its relationship to CVD and dietary intake | Strong |

| Dong et al., 2019 [18], China | CRCT | Fourth-grade students: I: n = 1361, C: n = 1364; Parents: I: n = 1306, C: n = 1340 C | Salt Reduction Model | NR | 8 mo. | Educational materials for salt reduction; watching popular science movies and children’s animations; six monthly salt reduction training sessions for students; publicity boards, campus radio, newspapers, etc. for publicity; winter vacation activities; and salt reduction theme activity and family component. | Parental knowledge of salt intake | Weak |

| Gewa et al., 2013 [27], Kenya | CRCT | First-grade students and siblings: vegetarian group: n = 80, meat group: n = 96, milk group: n = 101, control: n = 63; Parents: vegetarian group: n = 79, meat group: n = 91, milk group: n = 100, control: n = 72 | The Child Nutrition Project | NR | 24 mo. | Daily distribution of snacks to the school children based on the assigned group. Vegetarian supplement, milk supplement, meat supplement, and control (no food supplement provided). | Change in energy intake and markers of dietary quality among parents | Weak |

| Gunawardena et al., 2016 [28], Sri Lanka | CRC | Mothers of eighth-grade students: I: n = 152, C: n = 156 | NR | NR (own experience) | 12 mo. | Intervention group students were trained by facilitators through a series of discussions to acquire the ability to assess noncommunicable disease risk factors in their homes and take action to address them | Mothers’ weight, BMI, and self-reported consumption of food items | Strong |

| He et al., 2015 [20], He et al., 2016 [19] China | CRCT | Fifth-grade students: I: n = 141, C: n = 138; Adult family members: I: n = 278, C: n = 275 | School-EduSalt | NR | 3.5 mo. | Children in the intervention group were educated on the harmful effects of salt and how to reduce salt intake within the schools’ usual health education lessons. Children then relayed these salt reduction messages to their families | Salt intake (as measured by 24-h urinary sodium excretion), BP, and iodine consumption among adult family members | Strong |

| Katz et al., 2011 [29], USA | CRCT | Second- to fourth-grade students: I: n = 628, C: n = 552 | The Nutrition Detectives program | Social-Ecological Model | NR | Five mini-lessons and family outreach | Dietary pattern of parents | Weak |

| Knight et al., 1991 [30], Jamaica | Non-RCT | Fourth- and fifth-grade students: I: n = 423, C: n = 199; Mothers/guardians: I: n = 90, C: n = 47 | A child-to-child programme | NR | During the school year | Bi-weekly teacher training sessions to review what should be taught in the following two weeks and to assist in developing the curriculum. Action-oriented lessons for children. | Mothers’ nutritional knowledge | Weak |

| Newell et al., 2004 [31], Australia | Non-RCT | Third- to sixth-grade students: I: n = 307, C: n = 85; Parents: n = 613 | The Tooty Fruity Vegie project | NR | 2 yr. | Multi-strategy program including classroom-oriented strategies, parent-oriented strategies, school environment-oriented strategies, and school canteen-oriented strategies | Parental knowledge about recommended FV intakes | Weak |

| Øvrum and Bere 2014 [32], Norway | Natural experiment | First- to seventh-grade students; Parents: n = 1423 | Norwegian School Fruit Scheme | NR | NR | Free daily fruit or vegetable or subscription to one fruit or vegetable per day at a subsidized price | Parents’ FV intake | Moderate |

| Perry et al., 1998 [33], USA | CRCT (matched pair) | Fourth-grade students; Parents: n = 324 | 5- a- day Power Plus | SLT | 7 mo. | Behavioral curricula in the fourth and fifth grades, parental involvement/education, school foodservice changes, and industry involvement and support | Parents’ FV intake | Moderate |

| Reynolds et al., 2000 [34], USA | CRCT | Fourth-grade students; Parents: n = 1698 | The High 5 Project | SCT | Fall/winter 1994/95 | A classroom component with 14 lessons curriculum, in addition to booster sessions delivered during the second year; a parent component; and a food service component | Parents’ FV intake, knowledge of 5 a day and knowledge of low-fat food preparation | Strong |

| Sharma et al., 2016 [35], USA | Non-RCT | First-grade students. Parent-child dyads: I: n = 407, C: n = 310 | Brighter Bites | SCT, TPB | 16 wk. | Weekly distribution of fresh produce; nutrition education in schools and for parents; and weekly recipe tastings. | Parents’ FV intake | Moderate |

| Shi-Chang et al., 2004 [36], China | Non-RCT | Third- to fifth-grade primary students: n = 2575; First- and second-grade secondary students: n = 4277 (baseline survey); Parents and guardians: n = 998 | Health- promoting schools | NR | 18 mo. | School-wide health promotion activities, including school-based working groups; nutrition training for school staff; distribution of materials on school nutrition; nutrition education for students; student competitions; school-wide health promotion efforts; and outreach to families and communities | Nutrition knowledge of parents and guardians | Weak |

| Tak et al., 2007 [22] Tak et al., 2009 [21], Netherlands | Non-RCT. | Fourth-grade students: n = 953; Parents: n = 705 Fourth-grade students: I: n = 346, C: n = 425; Parents: I: n = 148 I, C: n = 287 | ‘Schoolgruiten’ | NR | NR | Improvement of FV availability and accessibility, bi-weekly free FV distribution at the mid-morning break, and school curriculum aimed at increasing knowledge and skills related to FV consumption | Parental knowledge about recommendations for fruit | Weak |

| Te Velde et al., 2008 [37], Spain, Norway and the Netherlands | CRCT | Fifth- and sixth-grade students; Mothers or female guardians: I: n = 415, C: n = 838 (baseline survey) | Pro Children intervention | NR | NR | A classroom component, a school component, a family component, and one optional component, which differed slightly between intervention sites | Total intake of FV and the intake of FV separately among mothers or female guardians | Moderate |

| Wang et al., 2016 [38], China | CRCT | Parents of seventh-grade students: I: n = 62, C: n = 61 | Health-promoting school | NR | 6 mo. | Health-promoting school intervention consisting of a wide range of health promotion activities in different domains including, School environment, curriculum, and Family involvement | Parents’ weekly frequency of consumption of food items, and nutrition knowledge | Strong |

| Woodhouse et al., 2012 [39], UK | Non-RCT (pilot) | Primary school students; Parents: I: n = 47 intervention (baseline survey) | Bostin Value | NR | 20 mo. | FV stall operated in the school playground twice a week, added initiatives (a loyalty card, 100 challenge week), family cooking sessions, and children’s tasting sessions | Parents’ FV consumption | Weak |

| Authors, Year | Parental Involvement | Outcomes of Interest | Outcome Measures | Findings |

| Bjelland et al., 2015, [23] | Fact sheets, brochures, and information sheets | Parental intakes of sugar-sweetened soft drinks and sugar-sweetened fruit drinks; Intake of FV | Self-administered questionnaire | Non-significant increase in maternal mean intake of fruits in the intervention group (mean = 9.1 servings/week) as compared to control group (mean = 8.4 servings/week) (p = 0.06). |

| Blom-Hoffman et al., 2008, [24] | Five interactive children’s books designed to complete with adult assistance to communicate a simple health message that the students learned at school | Knowledge of the “5 a Day” message | Parental interview using structured questionnaire | When compared to baseline, parents of the experimental group had higher percentage of correct answers about the “5 a Day” message at 1 year post baseline (21.6% higher, p < 0.05) and at 2 years post baseline (43.3% higher, p < 0.001). When compared to parent of the control group, they also had higher percentage of correct answer at 1 year post baseline (20.8% higher, p < 0.05), and at 2 years post baseline (40.1% higher, p < 0.001). |

| Burgess-Champoux et al., 2008, [25] | Weekly parent newsletters; bakery and grocery store tours; a ‘Whole Grain Day’ event | Self-reported intake of refined- and whole-grain foods | 12-item food frequency section modified from the Block FFQ (Intake over the past month) | Self-reported intake of refined-grain foods decreased significantly for parents in the intervention school (pre-post difference: −0.3, p < 0.05) compared to those in comparison school (p < 0.01) post-intervention. No significant group differences were found in whole grain intake. |

| Crockett et al., 1989, [26] | Hearty Heart and Friends: children’s activity and eating records brought home for discussion, curriculum books, worksheets and children’s homework assignments brought home by the child; Hearty Heart Home Team: weekly mails received by child and parent team including a rule book with instructions about the week’s activities, a Hearty Heart adventure storybook, a scorecard, equipment, souvenirs, poster-size team tips, and incentives for completing activities. | Knowledge about diet and its relationship to cardiovascular disease | Self-administered questionnaire (Three scales) | Home Team alone group and the Hearty Heart and Home Team group had significantly greater knowledge scores as compared to the control group and Hearty Heart alone groups across all three scales. |

| Dietary intake | Willett FFQ (Intake over the past two months) | There were no significant differences in dietary intake among the groups. | ||

| Dong et al., 2019, [18] | Four parent training meetings; 16 bi-weekly text messages about salt reduction. | Change in knowledge of salt intake | Self-administered questionnaire | After the intervention, intervention group parents had significantly higher awareness of the salt reduction knowledge than those of the control group (p < 0.01) |

| Gewa et al., 2013, [27] | / | Change in energy intake and markers of dietary quality among parents | Three non-consecutive 24 h recalls | A general decline in food quality and quantity was reported among parents of all groups. The decline in food quantity was only significant for the parents of the vegetarian group. Significant declines on at least one of the markers of dietary quality were seen among parents of vegetarian, meat, and control group. |

| Gunawardena et al., 2016, [28] | / | Mothers’ weight and BMI | Weight and height were measured by research team | Intervention group mothers had a significantly lower mean weight and BMI than as compared to control group (p < 0.0001); mean effect (95% CI) −2.49 (−3.38 to −1.60) kg for weight and −0.99 (−1.40 to −0.58) kg/m2 for BMI. |

| Mothers’ self-reported consumption of FV, whole-grain product, pulse as main dish, deep fried foods and SSBs | 27- item self-administered FFQ | No significant difference in individual-level food consumption between mothers of the two groups after the intervention. | ||

| He et al., 2015 [20], He et al., 2016 [19] | Educational materials in the form of a newsletter | Salt and iodine consumption among adult family members | 24-h urinary sodium and iodine excretion | The mean effect (95% CI) on salt consumption for adults in the intervention group compared to control group was −2.9 g/day (−3.7 to −2.2 g; p < 0.001), representing a 25% reduction. The mean effect on iodine was −11.4% (p = 0.03). |

| BP among adult family members | Trained researchers measured BP and pulse rate using a validated automatic blood pressure monitor | Compared to baseline, adults in both groups had an increase in systolic and diastolic BP. The increase in systolic BP was smaller in intervention group. The mean effect (95% CI) on systolic BP was −2.3 mmHg (−4.5 to −0.04 mmHg; p < 0.05). The effect on diastolic BP was not significant. | ||

| Katz et al., 2011, [29] | Written materials and/or parent information nights to introduce parent to the program | Dietary pattern of parents | Harvard Services FFQ | No significant improvements in dietary patterns from baseline between the parents of students in either group. |

| Knight et al. 1991, [30] | / | Mothers’ Nutritional knowledge | Interviewer- administered questionnaire | Mothers or guardians in the intervention group had significantly higher improvement in the mean nutrition score (from 4.17 to 5.10) compared to those from the control group (from 4.45 to 4.57) p < 0.05 |

| Newell et al., 2004, [31] | Cooking classes, FV promoting flyers and newsletter articles, FV tasting, FV promoting merchandise, Competition asking parents to send in their handy hints for getting their children to eat FV. | Parents’ knowledge about recommended fruit and vegetable intakes | Self-administered survey | Significantly more intervention school parents as compared to control parents correctly identified recommended daily fruit intake of two servings (72% vs. 63%; continuity adjusted χ2 = 4.313, p < 0.05) and recommended daily vegetables intake of three servings (48% vs. 28%; continuity adjusted χ2= 17.062, p < 0.0001) |

| Øvrum and Bere 2014, [32] | / | Parents’ FV intake | Internet survey | Parents of children who received free fruit at school ate on average 0.19 more portions of fruits daily or 12.5% more fruits than parents of children who attend schools with no fruit arrangement (p = 0.04). No significant differences in vegetable intake between groups were found. |

| Perry et al., 1998, [33] | Fourth grade parental involvement: 5 information /activity packet brought home by students to be completed with parents; Fifth grade parental involvement: 4 snack packs, contained food items, that students brought home to prepare as a snack for their families. | Parents’ FV intake | Telephone survey (Single item measured average FV intake) | No significant differences in average fruit and vegetable consumption between groups were observed. |

| Reynolds et al., 2000, [34] | Program overview at parent kick off night, assignment to be completed with children, brochures, and skills building materials | Parents’ FV intake, | Self-administered questionnaire (FV items from Health Habits and History Q) | Post-intervention: intervention group parents consumed more servings of FV combined compared to control parents (+0.29, p < 0.04); When examined separately, the difference between conditions was significant for vegetables (+0.17, p < 0.04) but not for fruit consumption; 1-year post-intervention: No differences were observed for parental FV consumption. |

| Parental knowledge of 5 a day & knowledge of low-fat food preparation | Self-administered questionnaire | Post-intervention: a significant positive effect on knowledge of five a day serving among intervention group. No significant differences on knowledge of low-fat preparation among intervention and control groups. 1-years post intervention: no significant differences on nutrition knowledge between groups | ||

| Sharma et al., 2016, [35] | Weekly distribution of produce and healthy recipe tastings during pick up time, health education in schools and for parents, handbooks and weekly recipe cards sent home with the parents. | Parents’ FV intake | The validated 10-item FV Screener by the National Institutes of Health (Intake over the past month) | Intervention group parents had a significant increase in fruit consumption from baseline to midpoint (8 weeks follow up) (+25 servings-day, p = 0.03) and post intervention (16 weeks follow up) (+0.25 servings-day, p = 0.01) compared to those in the control group. A significant increase in vegetable (+0.30 servings/day, p = 0.04) and in total FV consumption (+53 serving/day, p = 0.007) was also seen among parents of the intervention groups compared to those in the control group at midpoint assessment, but not post-intervention. |

| Shi-Chang et al., 2004, [36] | Students passing information about nutrition to their families, parents’ leaflet on healthy nutrition and school lunch menus that they could prepare at home, lectures and workshops at schools. | Nutrition knowledge | Questionnaires | Parents and guardians of the pilot schools demonstrated higher knowledge gain than those of the control schools in three areas: nutrients and their functions, Chinese dietary guidelines and adequate dietary principles. They also increased their knowledge in the areas of nutritional deficiencies and their symptoms (from 35% to 66.2%, p < 0.01) and nutrient-rich foods (from 38.8% to 66.8%, p < 0.01), while knowledge of these areas did not change significantly amongst parents and guardians at control schools. |

| Tak et al., 2007, [22] Tak et al., 2009, [21] | / | Knowledge of parent about recommendations for fruit | Self-administered survey | No significant differences were observed between groups at the first- and the second- year follow-ups. |

| Te Velde et al., 2008, [37] | Parents were encouraged to be involved in the project through their children’s homework assignments, parental newsletters and a parent version of the web-based computer-tailored tool for personalized feedback on their intake | Total intake of FV and the intake of FV separately among mothers or female guardians | 24-h recall | No significant intervention effects were observed regarding FV intake of the mothers at the first- and second-year follow-ups. |

| Wang et al., 2016, [38] | One 90-min lecture, distribution of publicity resources for parents (one time, before the workshop), monthly short message to parents | Frequency of consumption of food items among parents | FFQ (intake over the past seven days) | No significant differences were observed in parents’ consumption of different food items between the HPS School and the control school |

| Parents’ nutrition knowledge | Self-administered questionnaire | Significant difference in parents’ awareness rate of eight knowledge items (out of ten) between the HPS School and the Control School after intervention (p < 0.05) | ||

| Woodhouse et al., 2012, [39] | FV stall operated in the school playground twice a week, recipe cards, loyalty cards, family cooking sessions, and different promotion activities to promote take up for the “Family Cooking Sessions” | Parents’ FV intake | Self-administered survey | At the first follow-up, the mean portions of FV consumed by parents of the pilot school increased significantly from 2.4 to 3.1 (p = 0.03) for fruits and from 2.7 to 3.4 (p ≤ 0.001) for vegetables. The increase in fruits consumption was significantly higher than that of the comparison school (p = 0.02); At the second follow-up, the average of FV consumption by parents/carers at pilot school was not significantly different from either the baseline or the comparison school. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abderbwih, E.; Mahanani, M.R.; Deckert, A.; Antia, K.; Agbaria, N.; Dambach, P.; Kohler, S.; Horstick, O.; Winkler, V.; Wendt, A.S. The Impact of School-Based Nutrition Interventions on Parents and Other Family Members: A Systematic Literature Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2399. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14122399

Abderbwih E, Mahanani MR, Deckert A, Antia K, Agbaria N, Dambach P, Kohler S, Horstick O, Winkler V, Wendt AS. The Impact of School-Based Nutrition Interventions on Parents and Other Family Members: A Systematic Literature Review. Nutrients. 2022; 14(12):2399. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14122399

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbderbwih, Eman, Melani Ratih Mahanani, Andreas Deckert, Khatia Antia, Nisreen Agbaria, Peter Dambach, Stefan Kohler, Olaf Horstick, Volker Winkler, and Amanda S. Wendt. 2022. "The Impact of School-Based Nutrition Interventions on Parents and Other Family Members: A Systematic Literature Review" Nutrients 14, no. 12: 2399. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14122399

APA StyleAbderbwih, E., Mahanani, M. R., Deckert, A., Antia, K., Agbaria, N., Dambach, P., Kohler, S., Horstick, O., Winkler, V., & Wendt, A. S. (2022). The Impact of School-Based Nutrition Interventions on Parents and Other Family Members: A Systematic Literature Review. Nutrients, 14(12), 2399. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14122399