Consumer Eating Behavior and Opinions about the Food Safety of Street Food in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the motives (factors) of consumers choosing street food outlets?

- What consumer profiles can be identified according to the frequency of using street food outlets?

- How do consumers evaluate street food outlets in terms of food, including food quality, service, and hygiene?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

- Each respondent who agreed to participate in the survey was invited to complete the questionnaire. If necessary, explanations were provided.

- Everyone, independent of age, using the offer of the street food did not suffer from diseases requiring a special menu offer.

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Respondents

3.2. Use of Street Food Outlets by Polish Consumers

- -

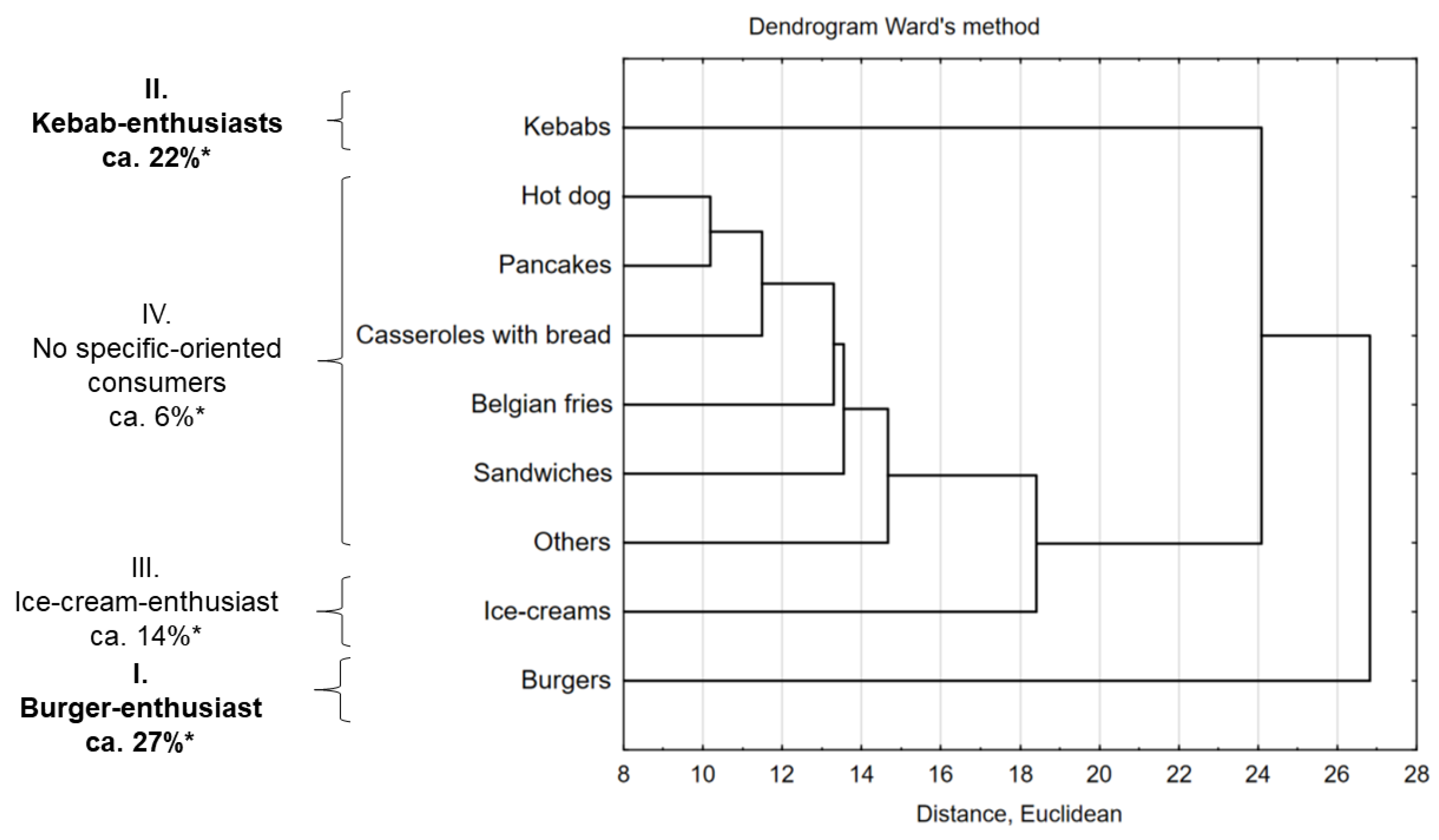

- burger-enthusiasts (I), young consumers (aged 19–30 years), mainly men, highly educated, with ‘good’ and ‘very good’ financial status (26.6%, p = 0.05) who used street food for three or four times a week;

- -

- kebab-enthusiasts (II), young respondents (aged 19–30 years), mainly men (22.6%, p = 0.05), who used street food for three or four times a week;

- -

- ice-cream enthusiasts (III), consumers with various sociodemographic groups (13.3%, p = 0.05), who used street food once a month;

- -

- no specific-oriented consumers (IV), respondents, mainly women, secondary educated, who used street food with different frequency.

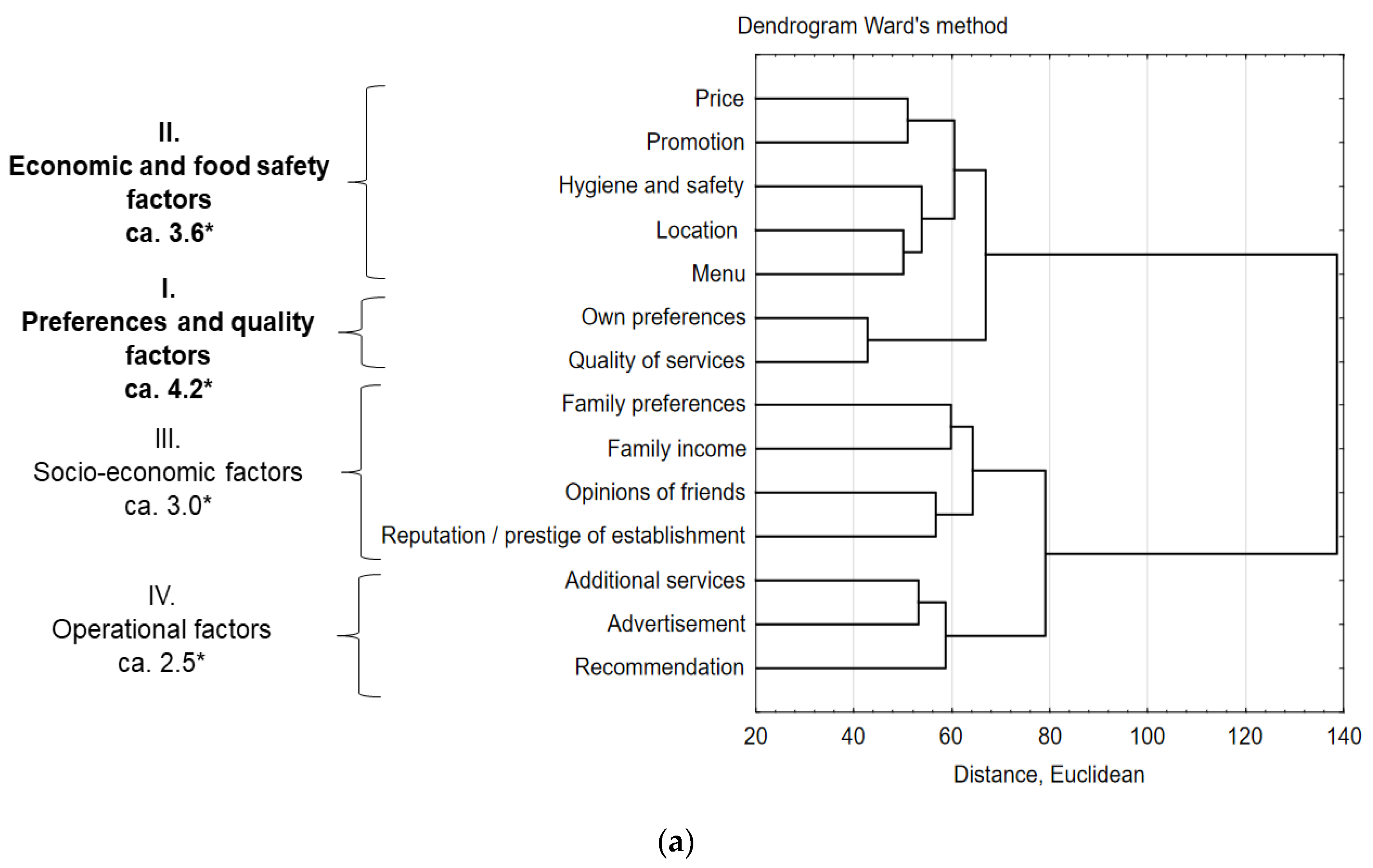

3.3. Reasons for Using Out-of-Home Eating and Choosing Catering Establishments

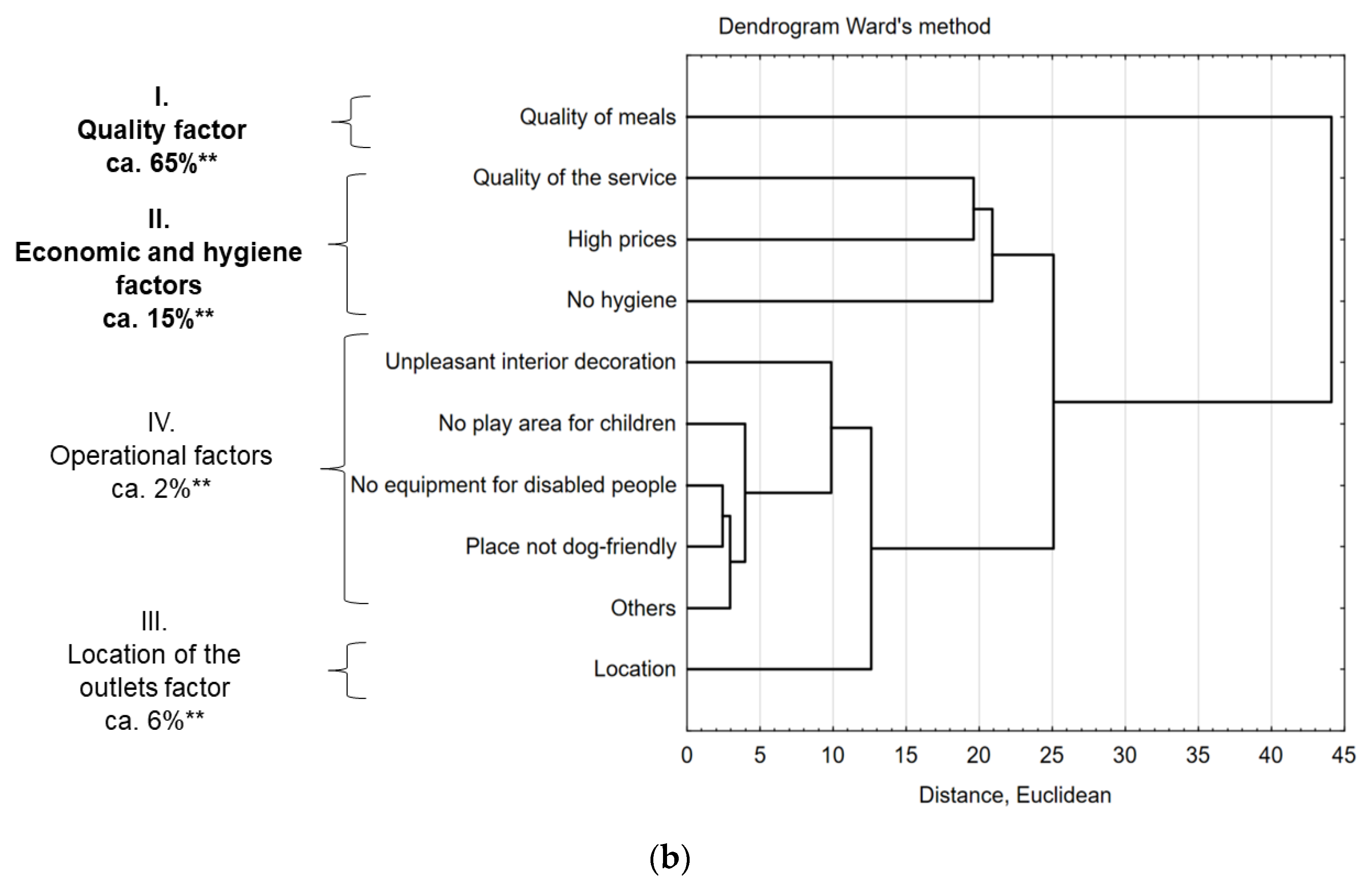

3.4. Consumer Opinion about Street Food Outlets

4. Discussion

4.1. Use of Street Food Outlets by Polish Consumers

4.2. Reasons for Using Out-of-Home Eating and Choosing Catering Establishments

4.3. Consumer Opinion about Street Food Outlets

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Question That Was Asked | Variants of Answers |

|---|---|

| Q1. How often do you use street food facilities? Choose the answers that suits you the best (only one option) | 1: Every day; 2: Three or four times a week; 3: Once a week; 4: Two or three times a month; 5: Once a month; 6: Once every two or three months; 7: Less than once every two or three months; 8: Never (if respondents choose this answer, they end the questionnaire) |

| Q2. Factors (14) that you take into account when choosing a catering establishment: 1: Price, 2: Own preferences, 3: Family preferences, 4: Opinions of friends, 5: Additional services, 6: The reputation/ prestige of establishment, 7: Family income, 8: Recommendation, 9: Hygiene and safety, 10: Location, 11: Menu, 12: Quality of services, 13: Promotion, 14: Advertisement. | Choose the degree of importance for each factor (5-point scale). 1: Unimportant 2: Moderately unimportant 3: Neutral 4: Moderately unimportant 5: Very important |

| Q3. What are you doing when you’re looking for a new catering establishment? Choose the answers that suits you the best (only one option) | 1: Ask your friends/ family; 2: Read articles on websites; 3: Check social media; 4: Check the establishment’s website; 5: Check websites with reviews of premises; 6: Read articles in the press; 7: Read internet blogs; 8: Others |

| Q4. Please comment on the following 7 statements about eating out: 1: I like to meet my friends, 2: It is convenient, 3: I don’t have time to prepare meals myself, 4: I want to celebrate special occasions, 5: I like to discover new flavors, 6: I don’t feel like cooking, I can’t cook, 7: It is due to work (e.g., business meetings). | Choose a comment for each statement (5-point scale): 1: Definitely do not agree; 2: Moderately do not agree; 3: Undecided; 4: Moderately agree; 5: Definitely agree |

| Q5. What discourages you from visiting an establishment again? Choose the answers that suits you the best (max. two option). | 1: Quality of meals; 2: Quality of service; 3: High prices; 4: Unpleasant interior decoration, 5: Location; 6: No play area for children; 7: No equipment for disabled people; 8: Place not dog-friendly; 9: Lack of hygiene; 10: Others |

| Q6. Have you ever complained about the service in the catering establishments? Choose the answers that suits you the best (only one option) | 1: Yes, very often; 2: Yes: sometimes; 3: Almost never; 4: No, never |

| Q7. Which street food outlets are your most favorite and/or most visited. Choose the answers that suits you the best (only one option). | Street food outlets serving: 1: Kebabs; 2: Burgers; 3: Hot dogs; 4: Belgian fries; 5: Casseroles with bread; 6: Pancakes; 7: Sandwiches; 8: Ice-Cream; 9: Others |

| Q8. Please comment on the following 13 statements: “Street food is: 1: A new type of cuisine that is gaining popularity”, 2: Another name for fast food”, 3: A better and healthier version of fast food”, 4: The cuisine designed for young people”, 5: An element of the city’s landscape that enhances its image”, 6: An unnecessary outlet that worsens the image of the city”, 7: A way to attract more tourists to the city”, 8: Cheap food”, 9: Local cuisine”, 10: An outlet with facilities that have a low hygiene level”, 11: Food with worse quality than typical (non-street) catering establishments”, 12: Food with better quality than typical (non-street) catering establishments”, 13: Food that quality is similar to typical (non-street) catering establishments”. | Choose a comment for each statement (5-point scale): 1: Definitely do not agree; 2: Moderately do not agree; 3: Undecided; 4: Moderately agree; 5: Definitely agree; |

| Q9. Observations concerning a recently visited street food premise, as well as 22 questions about hygiene in those facilities: | Choose the answers that suits you the best: Yes No |

| Q.9.1. Is the production area of the facilities hygienic? | |

| Q.9.2. Is there a waste bin available to employees in the production area and is it overflowing? | |

| Q.9.3. Are the floors and facility walls in good condition (clean, undamaged, made from a smooth, easy to wash and disinfect material)? | |

| Q.9.4. Are the production tops in good condition (clean, undamaged, made from a smooth, easy to wash and disinfect material)? | |

| Q.9.5. Are there any food pests (rodents, insects) in the production area? | |

| Q.9.6. Are there any personal items (phones, bags) of employees in the production area? | |

| Q.9.7. Are raw materials stored in proper condition (e.g., cold temperature)? | |

| Q.9.8. Are ready-to-eat products and waste stored separately? | |

| Q.9.9. Are catering tools clean and in a good condition (visually determined)? | |

| Q.9.10. Are there any unauthorized people in the production areas? | |

| Q.9.11. Do the raw materials look fresh? | |

| Q.9.12. Do workers handle packaging hygienically? | |

| Q.9.13. Do staff have clean hands during work? | |

| Q.9.14. Are the hands of any employee with injuries protected? | |

| Q.9.15. Do staff wear jewelry during work? | |

| Q.9.16. Do staff have appropriate working clothes? | |

| Q.9.17. Do staff protect their long hair (thus reducing the risk of food contamination)? | |

| Q.9.18. Do staff wash their hands properly and frequently (by observation)? | |

| Q.9.19. Is the payment process properly separated from production (e.g., by a different person accepting payment or covering of hands for hygienic tasks)? | |

| Q.9.20. Do staff wear and change disposable gloves frequently enough? | |

| Q.9.21. Do any staff have an illness (coughing, sneezing) that makes hygienic work difficult? | |

| Q.9.22. Do staff touch their face, hair, nose, or ears during food production? |

References

- WHO. World Health Organization. Essential Safety Requirements for Street-Vended Foods. Food Safety Unit, Division of Food and Nutrition, WHO/FNU/FOS/96. 1996. Available online: http://www.who.int/foodsafety/publications/fs_management/en/streetvend.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2020).

- Tinker, I. Street Foods: Traditional microenterprise in a modernizing world. Int. J. Politics Cult. Soc. 2003, 16, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Trafiałek, J.; Wiatrowski, M.; Głuchowski, A. An Evaluation of the Hygiene Practices of European Street Food Vendors and a Preliminary Estimation of Food Safety for Consumers, Conducted in Paris. J. Food Prot. 2018, 81, 1614–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinker, I. Street foods into the 21st century. Agric. Hum. Values 1999, 16, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, R.C.V.; dos Santos, S.M.C.; Silva, E.O. Street food and intervention: Strategies and proposals to the developing world. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2009, 14, 1215–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Suneetha, C.; Manjula, K.; Depur, B. Quality assessment of street foods in Tirumala. Asian J. Exp. Biol. Sci. 2011, 2, 207–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ag Bendech, M.; Tefft, J.; Seki, R.; Nicolo, G.F. Street Food Vending in Urban Ghana: Moving from an Informal to Formal Sector. Ghana Web 292956. Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. Regional Office for Africa. 23 November 2013. Available online: https://www.modernghana.com/news/504853/street-food-vending-in-urban-ghana-moving-from.html (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Gwiazdowska, K.; Kowalczyk, A. Zmiany upodobań żywieniowych i zainteresowanie kuchniami etnicznymi–przyczynek do turystyki (kulinarnej?).(Changes in culinary customs and attention to ethnic cuisines–contribution to (culinary?) tourism). Tur. Kult. 2015, 9, 6–24. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.; Lee, A.; Ok, C. The effects of consumers’ perceived risk and benefit on attitude and behavioral intention: A study of street food. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guigone, A. La cucina di strada: Con una breve etnografia dello street food Genovese. [The cuisine of the road: A brief ethnography of Genovese street food]. Mneme-Rev. Humanid. 2004, 3, 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Calloni, M. Street food on the move: A socio-philosophical approach. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 3406–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucan, S.C.; Maroko, A.R.; Burnol, J.; Varona, M.; Torrens, L.; Schechter, C.B. Mobile food vendors in urban neighborhoods–Implications for diet and diet-related health by weather and season. Health Place 2014, 27, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, M. How did Food Trucks Became so Popular in Los Angeles. 2016. Available online: http://www.nationalfoodtrucks.org/how_did_food_trucks_become_so_popular_in_los_angeles (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Weikel, K. Lunch traffic cools as competition heats up. Technomic 2016, July 29. Available online: https://technomic.com/lunch-traffic-cools-competition-heats (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Chukuezi, C.O. Food safety and hygienic practices of street food vendors in Owerri, Nigeria. Stud. Sociol. Sci. 2010, 1, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluko, O.O.; Ojeremi, T.T.; Olakele, D.A.; Ajidagba, E.B. Evaluation of food safety and sanitary practices among food vendors at car parks in Ile Ife, southwestern Nigeria. Food Control 2014, 40, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, S.A.; de Cassia, V.C.R.; Góes, J.A.W.; Santos, J.N.; Ramos, F.P.; de Jesus, R.B.; do Vale, R.S.; da Silva, P.S.T. Street food on the coast of Salvador, Bahia, Brazil: A study from the socioeconomic and food safety perspectives. Food Control 2014, 40, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, M.; Mahanta, L.; Goswami, J.; Minakshi, M.; Pegoo, B. Socio-economic profile and food safety knowledge and practice of street food vendors in the city of Guwahati, Assam, India. Food Control 2011, 22, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolanowski, W.; Trafiałek, J.; Drosinos, E.H.; Tzamalis, P. Polish and Greek young adults’ experience of low quality meals when eating out. Food Control 2020, 109, 106901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monney, I.; Agyei, D.; Owusu, W. Hygienic Practices among Food Vendors in Educational Institutions in Ghana: The Case of Konongo. Foods 2013, 2, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marutha, K.J.; Chelule, P.K. Safe Food Handling Knowledge and Practices of Street Food Vendors in Polokwane Central Business District. Foods 2020, 9, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annor, G.A.; Baiden, E.A. Evaluation of food hygiene knowledge attitudes and practices of food handlers in food businesses in Accra, Ghana. Food Nutr. Sci. 2011, 2, 830–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auad, L.I.; Ginani, V.C.; Stedefeldt, E.; Nakano, E.Y.; Santos Nunes, A.C.; Zandonad, R.P. Food Safety Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Brazilian Food Truck Food Handlers. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auad, L.I.; Ginani, V.C.; dos Santos Leandro, E.; Nunes, A.C.S.; Junior, L.R.P.D.; Zandonadi, R.P. Who is serving us? Food Safety Rules Compliance among Brazilian Food Truck Vendors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortese, R.D.M.; Veiros, M.B.; Feldman, C.; Cavalli, S.B. Food safety and hygiene practices of vendors during the chain of street food production in Florianopolis, Brazil: A cross-sectional study. Food Control 2016, 62, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, I.S.; Almeida, R.C.C.; Cerqueira, E.S.; Carvalho, J.S.; Nunes, I.I. Knowledge, attitudes and practices in food safety and the presence of coagulase positive, staphylococci on hands of food handlers in the schools of Camaçari, Brazil. Food Control 2012, 27, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha, D.T.; Stedefeldt, E.; de Rosso, V.V. The role of theoretical food safety training on Brazilian food handlers’ knowledge, attitude and practice. Food Control 2014, 43, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, G.S.; Bandeira, A.C.; Sardi, S.I. Zika virus outbreak, Bahia, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 1885–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samapundo, S.; Climat, R.; Xhaferi, R.; Devlieghere, F. Food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of street food vendors and consumers in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Food Control 2015, 50, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Nawawee, N.S.; Abu Bakar, N.F.; Zulfakar, S.S. Microbiological Safety of Street-Vended Beverages in Chow Kit, Kuala Lumpur. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafialek, J.; Drosinos, E.H.; Laskowski, W.; Jakubowska-Gawlik, K.; Tzamalis, P.; Leksawasdi, N.; Surawang, S.; Kolanowski, W. Street food vendors’ hygienic practices in some Asian and EU countries–A survey. Food Control. 2018, 85, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, M.; Trafialek, J.; Suebpongsang, P.; Kolanowski, W. Food hygiene knowledge and practice of consumers in Poland and in Thailand-A survey. Food Control 2018, 85, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollaard, A.M.; Ali, S.; van Asten, H.A.G.H.; Suhariah Ismid, I.; Widjaja, S.; Visser, L.G.; Surjadi, C.; van Dissel, J.T. Risk factors for transmission of foodborne illness in restaurants and street vendors in Jakarta, Indonesia. Epidemiol. Infect. 2004, 132, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, M.; Rahman, S.M.M.; Turin, T.C. Microbiological quality of selected street food items vended by school based street food vendors in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 166, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, X. Urban street foods in Shiziazhuand City, China: Current status, safety practices and risk mitigating strategies. Food Control 2014, 41, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baş, M.; Ersun, A.S.; Kivanç, G. The evaluation of food hygiene knowledge, attitudes, and practices of food handlers’ in food business in Turkey. Food Control 2006, 17, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscemi, S.; Maniaci, V.; Barile, A.M.; Rosafio, G.; Mattina, A.; Canino, B.; Verga, S.; Rini, G.B. Endothelial function and other biomarkers of cardiovacular risk in frequent consumers of street food. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 31, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trafiałek, J.; Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D.; Pałubicki, B.; Makuszewska, K. Higiena w zakładach gastronomicznych wytwarzających żywność w obecności konsumenta (Hygiene in catering establishments where food is produced in front of consumer). Żywność Nauka Technol. Jakość 2015, 22, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafiałek, J.; Drosinos, E.H.; Kolanowski, W. Evaluation of street food vendors’ hygienic practices using fast observation questionnaire. Food Control 2017, 80, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya, P. Food Truck Industry Growing, but Dozens of Unlicensed Vendors Exist. Kens5Eyewitness News 2015. Available online: http://www.kens5.com/news/local/food-truck-industry-growing-but-dozens-of-unlicensed-vendors-exist/54055864 (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Matre, J. 10things Food Trucks Won’t Say. 2012. Available online: http://www.marketwatch.com/story/10-things-food-trucks-wont-say-1342813986010 (accessed on 20 August 2019).

- Bhattacharjya, H.; Reang, T. Safety of street foods in Agartala, North East India. Public Health 2014, 128, 746–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.A.; Kurien, T.T.; Huppatz, C. Hepatitis A outbreak associated with kava drinking. Commun. Dis. Intell. Q. Rep. 2014, 38, E26–E28. [Google Scholar]

- Orlando, D.; Dennis, M.; Suci Hardianti, M.; Sigit-Sedyabuti, F.M.C. Mounting and effective response an outbreak of viral disease involving street food vendors in Indonesia. Chapter 18. In Case Studies in Food Safety and Authenticity. Lessons from Real-Life Situations; Hoorfar, J., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing Ltd.: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardani, K.K.; Susandari, H.; Wahyurini, O.D. Developing Street Food Vendor’s Vernacular Visual Identity to Support Tourism Industry in Surabaya. In Proceedings of the Empowering Design Quality in Creative Industry, International Conference on Creative Industry, Surabaya, Indonesia, 6–8 November 2013; Volume 2, pp. 369–373. [Google Scholar]

- Cuprasitrut, T.; Srisorrachatr, S.; Malai, D. Food safety knowledge, attitude and practice of food handlers and microbiological and chemical food quality assessment of food for making merit for monks in Ratchathewi District, Bangkok. Asia J. Public Health 2011, 2, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rane, S. Street vended food in developing world: Hazard Analyses. Indian J. Microbiol. 2011, 51, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kothe, C.I.; Schild, S.H.; Tondo, E.C.; Malheiros, P.S. Microbiological contamination and evaluation of sanitary conditions of hot dog street vendors in Southern Brazil. Food Control 2016, 62, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.; Gil, J.; Mourăo, J.; Peixe, L.; Antunes, P. Ready-to-eat street-vended food as a potential vehicle of bacterial pathogens and antimicrobial resistance: An exploratory study in Porto region, Portugal. In. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 206, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimi, B.A. Risk factors in street food practices in developing countries: A review. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2016, 5, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quereshi, S.; Azim, H. Hygiene practices and food safety knowledge among street food vendors in Kashmir. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2016, 4, 723–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairuzzaman, M.; Chowdhury, F.M.; Zaman, S.; Al Mamun, A.; Bari, M.L. Food safety challenges towards safe, healthy, and nutritious street foods in Bangladesh. Int. J. Food Sci. 2014, 2014, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Zang, W. Understanding China’s food safety problem: An analysis of 2387 incidents of acute foodborne illness. Food Control 2013, 30, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FSA–Food Standard Agency. Safer Food, Better Business. 2016. Available online: http://www.food.gov.uk/business-industry/sfbb (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- USDA–United States Department of Agriculture. Food Truck Programs. 2017. Available online: https:// usdaresearch.usda.gov/search?utf8=%E2%9C%93&affiliate=usda&query=food+truck+programs&commit=Search (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- CDC-Centers of Disease Control and Prevention-CDC. Multistate Outbreak of Salmonella Poona Infections Linked to Imported Cucumbers (Final Update) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/salmonelle/poona-09-15/index.html (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Gonzales, D. Food Truck Regulation: What Is Going on behind the Science. NBC Universal Media. 2012. Available online: http://www.nbc.miamiu.com/news/local/Food-Truck-Regulation-Whats-Going-On-Behind-the-Scenes-179743451.html#ixzz4QbLrr0Aq (accessed on 13 September 2020).

- Vanschaik, B.; Tuttle, J.L. Mobile food trucks: California EHS-net study on risk factors and inspection challenges. J. Environ. Health. 2014, 76, 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zuraw, L. Food safety on food trucks called A little more of a challenge. Food Safety News. 2015. Available online: http://www.foodsafetynews.com/2015/05/food-safety-on-food-trucks-a-little-more-of-a-challene/#.WE1WAGzrsxN (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- Mensah, P.; Yeboah-Manu, D.; Owusu-Darko, K.; Ablorday, A. Street foods in Acra, Ghana: How safe they? Bull. WHO 2002, 80, 546–554. [Google Scholar]

- Okumus, B.; Sonmez, S. An analysis on current food regulations for and inspection challenges of street food; Case of Florida. J. Culinary Sci. Technol. 2018, 17, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczuk, I.; Czarniecka-Skubina, E. Eating out in Poland: Status, perspectives and trends—A review. Sci. J. Univ. Szczec. Serv. Manag. 2015, 16, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Eurostat New Release: Statistics on the Food Chain From Farm to Fork. Stat/11/93, 22 June 2011. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/STAT_11_93 (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- Wołoszyn, A.; Ratajczak, K.; Stanisławska, J. Wydatki na usługi hotelarskie i gastronomiczne oraz ich determinanty w gospodarstwach domowych w Polsce (Expenditures on hotel and catering services in Polish households and its determinants). Studia Oeconomica Posnaniensa 2018, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Eurostat. Product Eurostat News. How Much Are Households Spending on Eating-Out? 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/EDN-20200101-2?fbclid=IwAR1VID3F54NSf2j8C0CRY1yfewAArTgxGhxiyOhXJh_VDC2QyZRWJhBd4Hc (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- van Iwaarden, J.; van der Wiele, T.; Ball, L.; Millen, R. Applying SERVQUAL to web sites: An exploratory study. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2003, 20, 919–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Berry, L.L.; Zeithaml, V.A. Refinement and reassessment of the SERVQUAL scale. J. Retail. 1991, 67, 420–450. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Codex Alimentarius, 4th ed.; Food Hygiene. Basic Texts; World Health Organization, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation (EC) No 852/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the hygiene of foodstuffs (OJ L 139, 30.4.2004, pp. 1–54). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32004R0852 (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- Freidberg, S. Editorial Not all sweetness and light: New cultural geographies of food. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2003, 4, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowska, E.; Czarniecka-Skubina, E. Catering services in Poland and in selected countries. Sci. J. Univ. Szczec. Serv. Manag. 2015, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiak, A. Gastronomia jako atrakcja turystyczna Łodzi. Turyzm 2015, 25, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polska na talerzu 2015. Raport MAKRO Cash and Carry, IQS. 2015. Available online: https://mediamakro.pl/pr/294746/co-gdzie-za-ile-jadamy-na-miescie-raport-polska-na-talerzu-2015 (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Polska na talerzu 2016. Raport MAKRO Cash and Carry, IQS. 2016. Available online: https://mediamakro.pl/pr/313540/jak-ksztaltuja-sie-preferencje-kulinarne-polakow-raport-polska-na-talerzu-2016 (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Polska na talerzu 2017. Raport MAKRO Cash and Carry, IQS. 2017. Available online: https://mediamakro.pl/pr/369536/pizzerie-food-trucki-czy-targi-sniadaniowe-najnowsze-trendy-w-raporcie (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Polska na talerzu 2018. Raport MAKRO Cash and Carry, IQS. 2018. Available online: https://mediamakro.pl/pr/394477/jak-polacy-zamawiaja-jedzenie-w-jakich-mediach-spolecznosciowych-szuka (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Polska na talerzu 2019. Raport MAKRO Cash and Carry, IQS. 2019. Available online: https://mediamakro.pl/pr/460369/tradycyjna-polska-kuchnia-wciaz-kroluje-na-naszych-talerzach-najnowsze (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Kowalczuk, I. Consumer Behavior on the Foodservice Market-Marketing Aspect; SGGW: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Levytska, G.; Kwiatkowska, E. Zachowania konsumentów na rynku nowoczesnych centrów handlowych (Consumer behavior in the modern shopping centers). Zesz. Nauk. SGGW-Ekon. Organ. Gospod. Żywnościowej 2008, 71, 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Raport IAB Polska. Wpływ Internetu na Proces Zakupowy Produktów i Usług. E-Konsumenci. Consumer Journey Online 2013. Available online: https://www.iab.org.pl/baza-wiedzy/e-konsumenci-consumer-journey-online-wplyw-internetu-na-proces-zakupowy-produktow-i-uslug-raport-iab-polska-e-konsumenci -consumer-journey-online/ (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Raport ArC Rynek i Opinia: Konsument w Restauracji. Seminarium Naukowe Marketing ze Smakiem, Warsaw. 2014. Available online: https://ssl-administracja.sgh.waw.pl/pl/br//Documents/Konsument_w_ restauracji_wyniki_badania_ARC.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Iriguler, F.; Ozturk, B. Street Food as Gastronomic Tool in Turkey. Int. Gastron. Tour. Congr. Proceedings of the II. International Gastronomic Tourism Congress, İzmir, Turkey. 2016, December, 49–64. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314950514_Street_Food_as_a_Gastronomic_Tool_in_Turkey (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Steyn, N.P.; Mchiza, Z.; Hill, J.; Davids, Y.D.; Venter, I.; Hinrichsen, E.; Opperman, M.; Rumboeow, J.; Jacobs, P. Nutritional contribution of street foods to the diet of people in developing countries: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 17, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, A.C.; Şanlier, N. Street food consumption in terms of the food safety and health. J. Hum. Sci. 2016, 13, 4072–4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulmajid, N.; Bautista, M.K.; Bautista, S.; Chavez, E.; Dimaano, W.; Barcelon, E. Heavy metals assessment and sensory evaluation of street vended foods. Int. Food Res. J. 2014, 21, 2127–2131. [Google Scholar]

- Nonato, I.L.; Minussi, I.O.D.A.; Pascoal, G.B.; De-Souza, D.A. Nutritional issues concerning street foods. J. Clin. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Morais, I.L.; Lunet, N.; Albuquerque, G.; Gelormini, M.; Casal, S.; Damasceno, A.; Pinho, O.; Moreira, P.; Jewell, J.; Breda, J.; et al. The Sodium and Potassium Content of the Most Commonly Available Street Foods in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan in the Context of the FEEDCities Project. Nutrients 2018, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calliope, S.R.; Samman, N.C. Salt Content in Commonly Consumed Foods and Its Contribution to the Daily Intake. Nutrients 2020, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyn, N.P.; Labadarios, D.; Nel, J.H. Factors which influence the consumption of street foods and fast foods in South Africa–A national survey. Nutr. J. 2011, 10, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyn, N.P.; Labadarios, D. Street foods and fast foods: How much do South Africans of different ethnic groups consume? Ethnicity Dis. 2011, 21, 462–466. [Google Scholar]

- Namugumya, B.S.; Muyanja, C. Contribution of street foods to the dietary needs of street food vendors in Kampala, Jinja and Masaka districts, Uganda. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 15, 1503–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, V.; Downs, S.M.; Ghosh-Jerathj, S.; Lock, K.; Singh, A. Unhealthy fat in street and snack foods in low-socioeconomics settings in India: A case study of the food environments of rural villages and an urban slum. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2016, 48, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafiałek, J.; Kaczmarek, S.; Kolanowski, W. The risk analysis of metallic foreign bodies in food products. J. Food Qual. 2016, 39, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, B.M.; Volel, C.; Finkel, M. Safety of vendor-prepared foods: Evaluation of 10 processing mobile food vendors in Manhattan. Public Health Rep. 2003, 118, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheinländer, T.; Olsen, M.; Bakang, J.A.; Takyi, H.; Konradsen, F.; Samuelsen, H. Keeping up Appearances: Perceptions of Street Food Safety in Urban Kumasi, Ghana. J. Urban Health 2008, 85, 952–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Features of Population | Group | Number of Respondents (n) | Percentage of Respondents (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Gender | - | 1300 | 100.0 |

| women | 705 | 54.2 | |

| men | 595 | 45.8 | |

| Age | up to 18 years old | 190 | 14.6 |

| 19–30 years old | 912 | 70.2 | |

| 31–55 years old | 198 | 15.2 | |

| Education | vocational and elementary school | 110 | 8.5 |

| secondary school | 676 | 52.0 | |

| higher education (university) | 514 | 39.5 | |

| Dwelling place | city over 250,000 inhabitants | 620 | 47.7 |

| city up to 250,000 inhabitants | 291 | 22.4 | |

| city up to 50,000 inhabitants | 211 | 16.2 | |

| village | 178 | 13.7 | |

| Self-reported financial status | ‘very good’ | 197 | 15.2 |

| ‘good’ | 585 | 45.0 | |

| ‘not good not bad’ | 385 | 29.6 | |

| ‘bad’ | 133 | 10.2 |

| Reasons | Average ± SD | Q25 | Median | Q75 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I like to meet my friends | 3.71 ± 1.28 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| It is convenient | 3.69 ± 1.15 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I don’t have time to prepare meals myself | 3.10 ± 1.33 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| I want to celebrate special occasions, | 3.45 ± 1.36 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

| I like to discover new flavors | 3.72 ± 1.27 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I don’t feel like cooking, I can’t cook, | 3.05 ± 1.40 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| It is due to work (e.g., business meetings) | 2.53 ± 1.37 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Opinion about Street Food | Average ± SD | Q25 | Median | Q75 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: A new type of cuisine that is gaining popularity | 3.41 ± 1.21 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| 2: Another name for fast food | 2.97 ± 1.29 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3: A better and healthier version of fast food | 2.96 ± 1.24 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4: The cuisine designed for young people | 2.84 ± 1.30 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5: An element of the city’s landscape that enhances its image | 2.67 ± 1.29 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6: An unnecessary outlet that worsens the image of the city | 2.27 ± 1.27 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 7: A way to attract more tourists to the city | 2.93 ± 1.26 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 8: Cheap food | 3.23 ± 1.20 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 9: Local cuisine | 2.72 ± 1.22 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 10: An outlet wit facilities that have a low hygiene level | 2.54 ± 1.18 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 11: Food with worse quality than typical (non-street) catering establishments | 2.43 ± 1.05 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 12: Food with better quality than typical (non-street) catering establishments | 2.87 ± 0.80 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 13: Food that quality is similar to typical (non-street) catering establishments | 3.06 ± 1.12 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Opinion of Consumers * | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Q.9.1. Is the production area of the facilities hygienic? | 82.15 | 17.85 |

| Q.9.2. Is there a waste bin available to employees in the production area and is it overflowing? | 86.69 | 13.31 |

| Q.9.3. Are the floors and facility walls in good condition (clean, undamaged, made from a smooth, easy to wash and disinfect material)? | 78.62 | 21.38 |

| Q.9.4. Are the production tops in good condition (clean, undamaged, made from a smooth, easy to wash and disinfect material)? | 78.08 | 21.82 |

| Q.9.5. Are there any food pests (rodents, insects) in the production area? | 22.92 | 77.08 |

| Q.9.6. Are there any personal items (phones, bags) of employees in the production area? | 44.69 | 55.31 |

| Q.9.7. Are raw materials stored in proper conditions (e.g., cold temperature)? | 79.00 | 21.00 |

| Q.9.8. Are ready-to-eat products and waste stored separately? | 20.77 | 79.23 |

| Q.9.9. Are catering tools clean and in a good condition (visually determined)? | 80.62 | 19.38 |

| Q.9.10. Are there any unauthorized people in the production areas? | 37.38 | 62.62 |

| Q.9.11. Do the raw materials look fresh? | 82.54 | 17.46 |

| Q.9.12. Do workers handle packaging hygienically? | 75.77 | 24.23 |

| Q.9.13. Do staff have clean hands during work? | 81.85 | 18.15 |

| Q.9.14. Are the hands of any employee with injuries protected? | 20.54 | 79.46 |

| Q.9.15. Do staff wear jewelry during work? | 51.00 | 49.00 |

| Q.9.16. Do staff have appropriate working clothes? | 69.54 | 30.46 |

| Q.9.17. Do staff protect their long hair (thus reducing the risk of food contamination)? | 67.85 | 32.15 |

| Q.9.18. Do staff wash their hands properly and frequently (by observation)? | 74.77 | 25.23 |

| Q.9.19. Is the payment process properly separated from production (e.g., by a different person accepting payment or covering of hands for hygienic tasks)? | 71.31 | 28.69 |

| Q.9.20. Do staff wear and change disposable gloves frequently enough? | 58.54 | 41.46 |

| Q.9.21. Do any staff have an illness (coughing, sneezing) that makes hygienic work difficult? | 17.69 | 82.31 |

| Q.9.22. Do staff touch their face, hair, nose, or ears during food production? | 40.08 | 59.92 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wiatrowski, M.; Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Trafiałek, J. Consumer Eating Behavior and Opinions about the Food Safety of Street Food in Poland. Nutrients 2021, 13, 594. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020594

Wiatrowski M, Czarniecka-Skubina E, Trafiałek J. Consumer Eating Behavior and Opinions about the Food Safety of Street Food in Poland. Nutrients. 2021; 13(2):594. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020594

Chicago/Turabian StyleWiatrowski, Michał, Ewa Czarniecka-Skubina, and Joanna Trafiałek. 2021. "Consumer Eating Behavior and Opinions about the Food Safety of Street Food in Poland" Nutrients 13, no. 2: 594. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020594

APA StyleWiatrowski, M., Czarniecka-Skubina, E., & Trafiałek, J. (2021). Consumer Eating Behavior and Opinions about the Food Safety of Street Food in Poland. Nutrients, 13(2), 594. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020594