1. Introduction

Urbanization significantly alters Earth’s land surface condition and has profound impacts on regional-to-global terrestrial ecosystem processes and services [

1,

2,

3]. Vegetation phenology, the interannual rhythm of the start, progress and ending of vegetation growth, manifests these impacts. Therefore, understanding the effect of urbanization on vegetation phenology is a critical step to study the broader influences of urbanization on the environment. Urban vegetation provides crucial ecosystem services, such as reducing noise, absorbing pollutants, serving as habitats for some migratory and local birds. Previous studies confirmed that urban areas experience higher temperature than the surrounding rural regions [

4,

5,

6]. This phenomenon is known as the urban heat island (UHI) effect. An accurate knowledge of the impacts of UHI on vegetation phenology can help mitigate the vulnerability of urban ecosystem services. For example, quantifying the effects of UHI on vegetation phenology can reveal the potential phenological mismatches between vegetation, insects and birds at higher trophic levels [

7,

8], thus providing clues for biodiversity protection in the urban ecosystem. Moreover, vegetation phenology controls the timing of pollen production, and thus the allergy season in urban areas [

9]. Understanding the urbanization-induced phenological changes can provide valuable information for public health risk forecasting [

9,

10].

Given the significant progress in detecting phenological changes of the natural ecosystems that are generally controlled by temperature [

11,

12,

13] and precipitation [

14,

15], it remains less clear how the process of urbanization has altered vegetation phenology in the heterogeneous urban environment. Manipulative experiments and ground observations have documented earlier starts of growing seasons (SOS) and later ends of growing seasons (EOS) in the urban center than the surrounding rural areas [

16,

17]. While those studies provide important evidences of effects of urbanization on vegetation phenology, site-based observations cannot provide an assemble understanding of spatially-explicit phenological changes in urban areas due to the lack of standard data collection protocols and consistent data analysis methods [

18]. Remote sensing observations offer consistent quantitative measurements of land surface properties, making long-term satellite observations ideal resources for monitoring vegetation phenology [

19]. Many algorithms have been developed to estimate phenological metrics based on time series of vegetation indices derived from Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) and Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. More specifically, studies have reported an increase of 7.6 days in the length of growing season (LOS) caused by urbanization in the Eastern United States [

26]. Zhang et al. [

27] found an increase of LOS by 15 days around urban centers, and the lengthening of LOS extends up to 10 km beyond urban margin. Zhou et al. [

28] found SOS were 11.9 days earlier and EOS were 5.4 days later around urban centers than their surrounding rural areas in China’s 32 cities. However, our understanding of urban phenology with the coarse spatial resolution images in urban environments is limited due to the complexity of the urban environment. The localized heterogeneity in urban phenology changes as a result of spatial variations in urban land-cover/land-use (LCLU) composition and configuration cannot be revealed using coarse spatial resolution images.

The opening of the Landsat archive has enabled the pixel-wise long-term time series analyses at finer spatial resolution [

29]. Fisher et al. [

30] demonstrated that the average phenology of New England deciduous forests could be mapped at the Landsat scale using multitemporal Landsat observations that were organized by day of year (DOY). Melaas et al. [

31,

32] extended the algorithm in a way that allowed the detection of interannual variability in phenology and validated the method in North American temperate and boreal deciduous forest. These approaches have only recently been applied to urban areas [

33,

34], and there remain substantially unrealized potential for leveraging them to better understand how urbanization affects phenological changes. More importantly, landscape patterns not only reflect the urban development and their socioeconomic drivers [

35,

36,

37], but also significantly influence UHI [

38]. However, the relationship between landscape pattern and vegetation phenology is poorly understood. Therefore, this research aims to investigate the impacts of urbanization, as well as the urban landscape composition and configuration on vegetation phenology from 1984 to 2015 in Shanghai, China. We addressed the following two questions: (1) How does vegetation phenology vary spatially and temporally along a rural-to-urban transect over the past three decades? (2) How do landscape composition and configuration affect those variations of vegetation phenology? We hypothesize that not only the urban center has longer LOS, but also the landscape composition and configuration influence the spatial patterns of vegetation phenology.

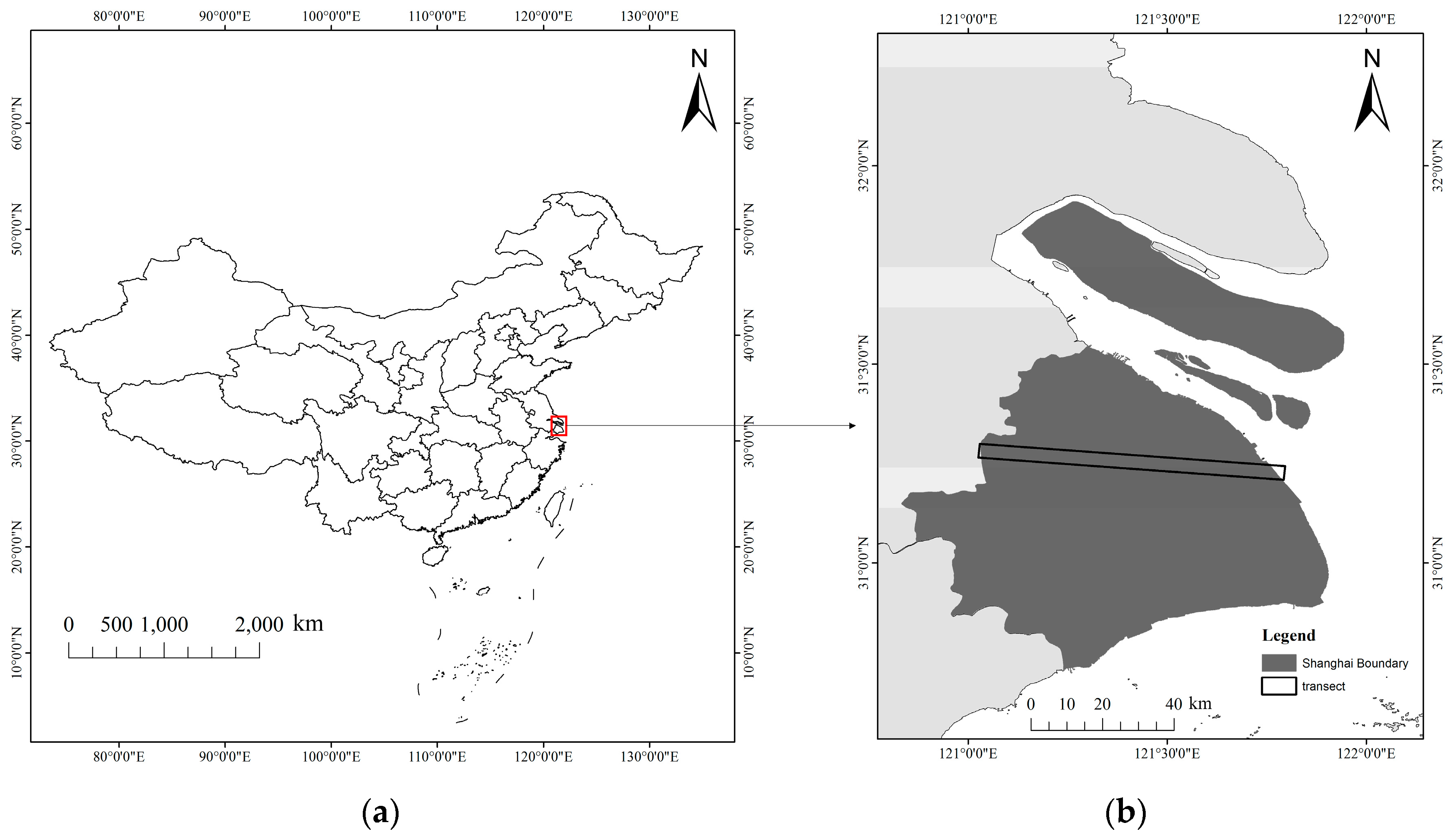

4. Results

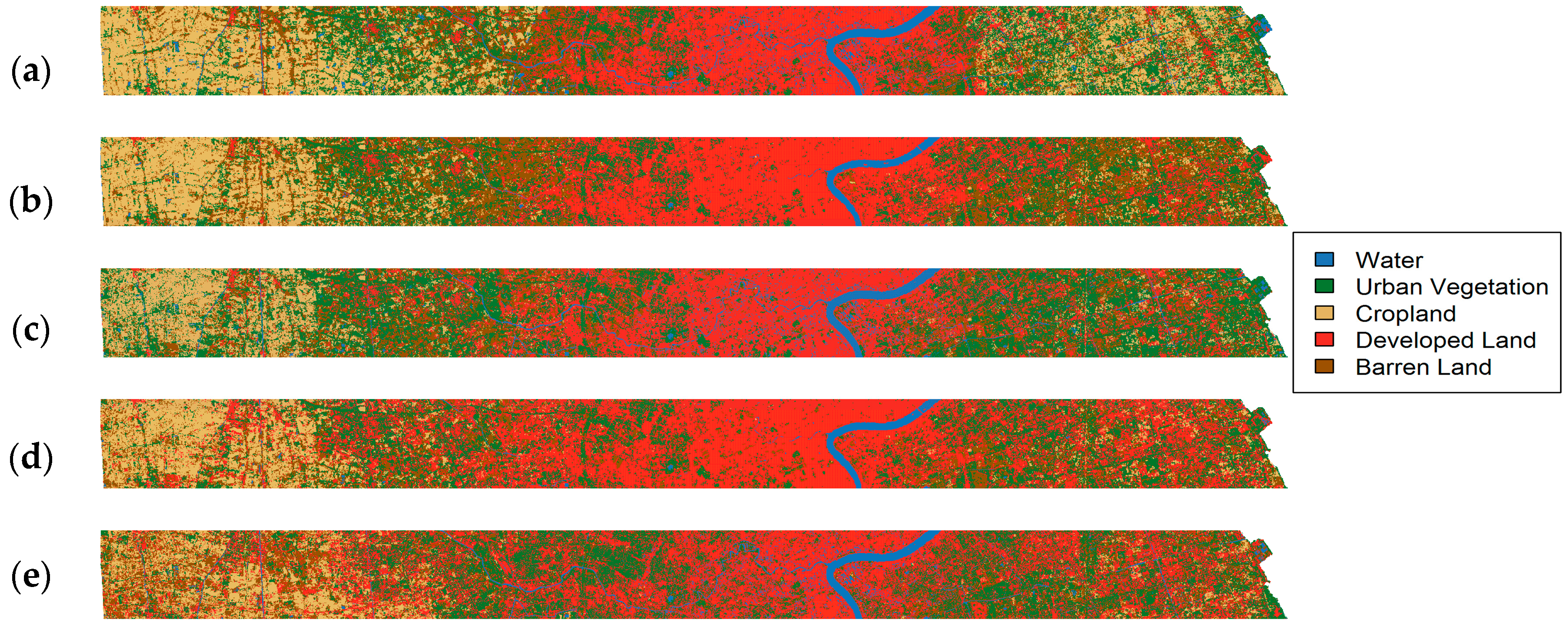

4.1. AASG Classification Results

Figure 2 presents the results of AASG classification in the east-west transect for years 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015, respectively. The overall accuracy for the land cover maps ranged from 74% to 84%, more details about confusion matrix can be found in the

supplementary material (Tables S1–S5). The east-west transect had experienced a dramatic urban expansion from 1995 to 2015.

Table 4 shows the percentages of land cover types in these maps. A large proportion of the cropland have been replaced by developed land.

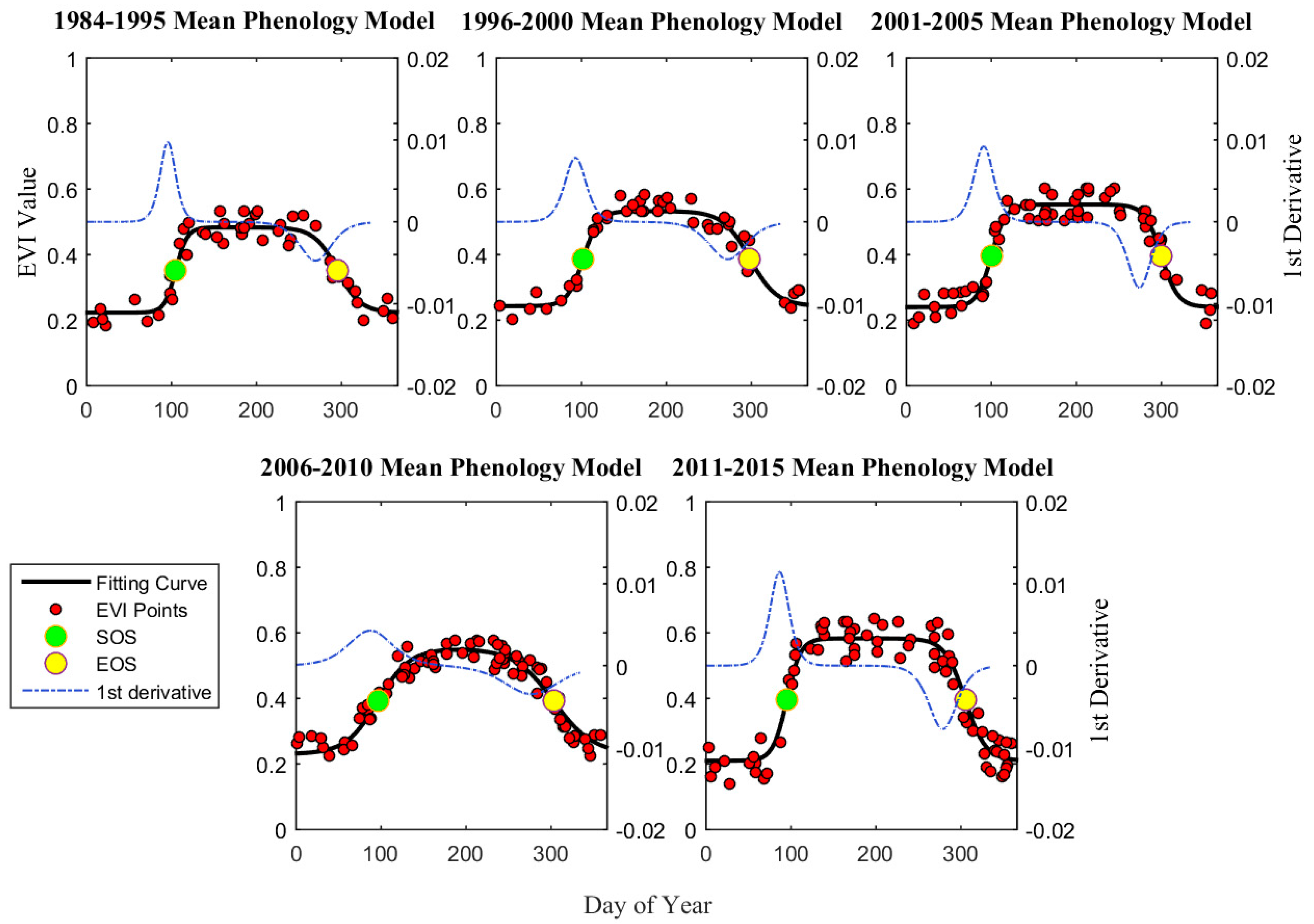

4.2. Phenological Curves

Figure 3 presents the mean phenology model of the five time periods based on multi-temporal Landsat images for a pixel of typical urban vegetation. Phenology curves in

Figure 3 clearly shows inflection points (also mid-points between maximum and minimum of the fitted EVI time series for the difference logistic function) in the spring greening-up and fall senescence. These inflection points can be easily and consistently identified from the phenology curves and are considered as the SOS and EOS dates in this study.

Figure 3 also shows that the rate of change in EVI along the growing season varies from period to period.

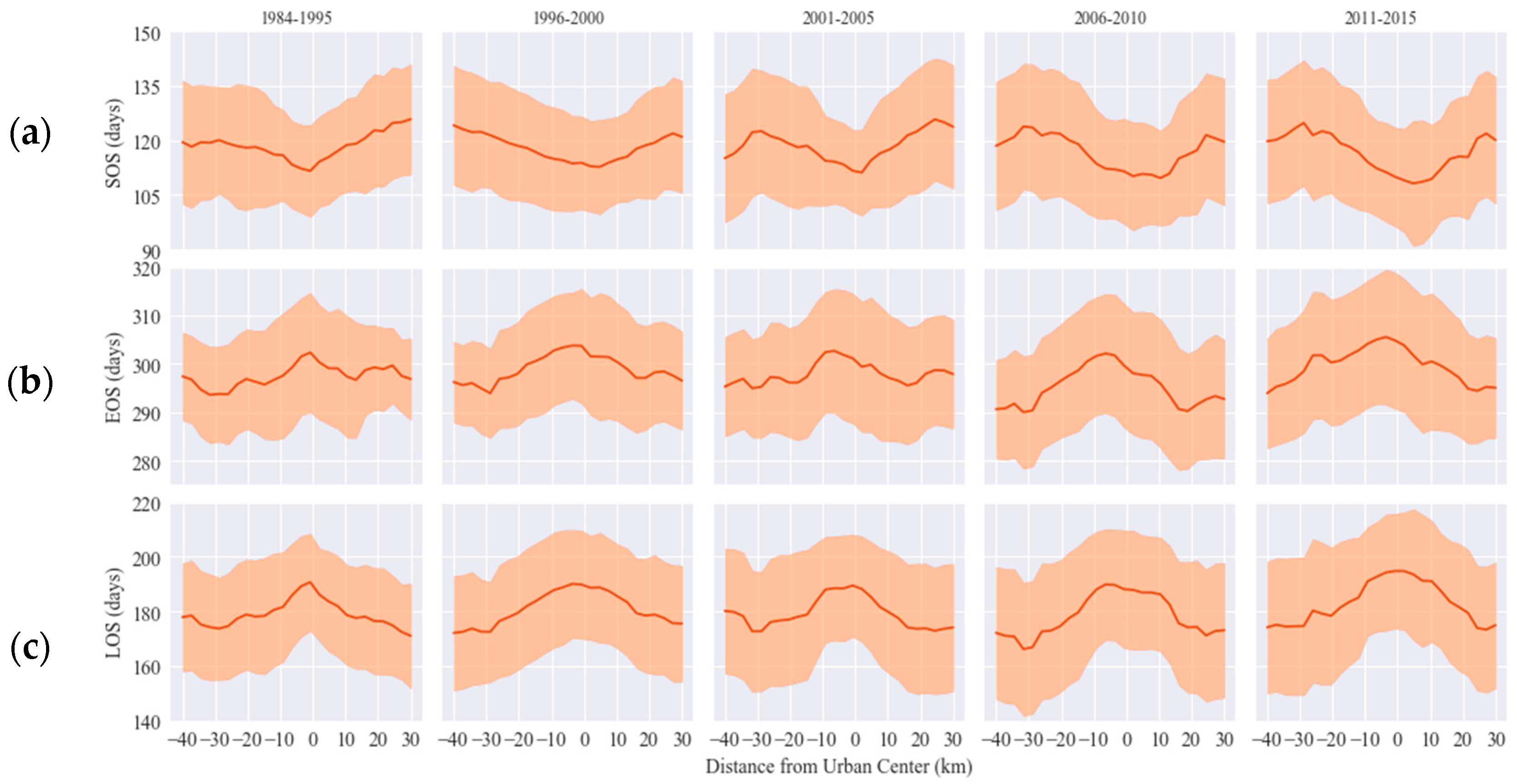

4.3. Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Vegetation Phenology

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 present images showing the SOS, EOS, and LOS at Landsat spatial resolution for urban vegetation along the east-west transect over the five periods (the gray areas are non-vegetation land or missing data).

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 clearly show that the phenology cycle in the urban centers starts earlier, and ends later, leading to a longer growing season when compared with the surrounding less-developed regions.

Figure 7 shows the mean and standard deviation of the phenological metrics along the transect. We see a clear pattern that vegetation in the urban center greens up earlier and senesces later compared to vegetation located in the rural areas for all five time periods. On average, SOS occurs 5–10 days earlier, and EOS appears about 5–11 days later, leading to LOS being longer by about 10–21 days in the urban center compared with the rural regions. In addition, we see substantial localized variations in SOS, EOS, and LOS along the transect, probably caused by the spatial heterogeneity of the urban environment. The local variations in phenology metrics can be as much as 10 days.

Table 5 shows the percentages of longer LOS (standardized anomalies greater than 1), shorter LOS (standardized anomalies smaller than −1), and no-change of LOS (standardized anomalies between −1 and 1) within the transect for urban vegetation in the five periods. The percentage of longer LOS seems to increase while the percentage of shorter LOS seems to decrease through the five periods.

4.4. Pearson Correlations between SOS, EOS, LOS, and Landscape Metrics

Table 6 shows Pearson correlation coefficients between landscape level metrics and phenology metrics for urban vegetation in the three time periods including 1984–1995, 1996–2000, and 2001–2005 when we have high spatial resolution air photos. According to

Table 6, CONTAG is significantly correlated with phenology metrics, except for the 2001–2005 interval. The correlations between SHEI, SHDI, and phenology metrics are also significant during the 1984–1994 and 1996–2000 intervals (except SOS during 1984–1995). PD is significantly correlated with phenology metrics, except during the 1984–1995 interval. More specifically, both PD and CONTAG have positive correlations with SOS, while having negative correlations with EOS and, as a result, negative correlations with LOS. Both SHDI and SHEI exhibit the opposite correlations with phenology metrics compared with CONTAG and PD. The correlations for both LSI and ED with phenology metrics are more complicated as they are not consistent across three time periods. For example, LSI is negatively correlated with SOS during 1984–1995, but it is positively correlated with SOS during 2001–2005.

Table 7 shows the Pearson correlation coefficients between class-level pattern metrics and phenology metrics for urban vegetation in three time periods, including 1984–1995, 1996–2000, and 2001–2005. The class-level PLAND of RE and PF are significantly negatively related with SOS and positively related with EOS, and, thus, positively with LOS. Those correlations are also consistent across three time periods. Meanwhile, higher PLAND of both IN and TR are significantly associated with earlier SOS and later EOS and, as a result, longer LOS except during 2001–2005. In contrast, PLAND of both AG and WA show the opposite correlations with phenology metrics. The higher PLAND of AG/WA tends to be correlated with shorter growing seasons (LOS) from both later greening (SOS) and earlier senescence (EOS). As for the PLAND for VG, the correlations are only significant during 1984–1995.

PD for PF exhibits a significant negative correlation with SOS and a positive correlation with EOS, thus, a positive correlation with LOS. The correlations are consistent across three time intervals. In comparison, the signs of correlations between PD for AG/VG and phenology metrics are opposite to the signs of correlations between PD for PF. As for PD of other LCLU types, the correlations between PD and phenology metrics are not consistent. For example, PD for IN in 1984–1995 is negatively correlated with SOS, while it is positively correlated with SOS in 2001–2005.

ED for RE, PF, IN, and TR are negatively correlated with SOS, but they are positively correlated with EOS, thus, positively correlated with LOS. These LCLU types are mostly dominated by impervious surfaces, contributing to UHI effects. In addition, vegetation associated with these land-use types are often actively managed, particularly irrigation and fertilization. Therefore, it is not surprising that higher ED for these land-use types lead to longer LOS. Meanwhile, higher ED for WA, VG and AG tend to have later SOS, earlier EOS and, thus, shorter LOS. LSI for PF, IN, TR, VG, and WA have similar correlations with phenology metrics as ED does. However, LSI for RE only has significant correlations with phenological metrics in 1996–2000.

CLUMPY for LCLU types does not show consistent significant correlation across three time intervals except for WA and VG. Specifically, correlations between phenology metrics and CLUMPY for WA/VG indicate that higher CLUMPY values have earlier SOS, later EOS and, thus, longer LOS.

5. Discussion

This research derived the mean phenological metrics (SOS, EOS, and LOS) for urban vegetation along a rural-to-urban transect in Shanghai from Landsat images by fitting sigmoid-family functions on EVI time series organized by DOY from multiple years. While this approach did not allow for detection of inter-annual variations within each time period, it produced 30 m × 30 m phenology metrics within each time intervals.

Figure 3 shows that these functions capture the temporal patterns of EVI very well, and provide a means to consistently identify the phenological metrics across the time intervals. We also clearly see that rates of change in EVI were different across different time periods, which indicates that the assumptions (maximums and shapes of smoothed EVI curve remain the same from year to year) in Landsat phenology algorithm developed by Melaas et al. [

31] may not hold in the heterogeneous urban environments. However, the greatest weakness of this study is the lack of data for accuracy assessment. This is a common problem for large area phenology study based on satellite images. However, the general spatiotemporal patterns we identified along the rural to urban gradient fit our expectation, although we do not know the specific picture for Shanghai without this study.

Recent research has suggested that the growing season of vegetation in cities is longer compared with the surrounding rural regions because of UHI effects [

9,

17,

26,

27,

33,

34]. Our results support this conclusion, providing a refined characterization of interactions between composition and configuration of local LCLU types and spatial patterns of vegetation phenology. Our hypothesis suggested that landscape metrics influenced vegetation phenology was supported by the significant correlations between phenology metrics and landscape metrics at both landscape level and class level. Therefore, UHI is not the only factor that influences phenology of urban vegetation. Specifically, we found that an increase in PD at the landscape level had a shorter growing season. This can be explained by the negative correlation between the heterogeneity and the land surface temperature (LST) [

38]. Since vegetation phenology is very sensitive to temperature [

33,

54], higher LST leads to earlier SOS and later EOS, thus, a longer LOS. However, an increase of heterogeneity can reduce the LST [

38], thus weakening the UHI effect on the growing season. However, we also found low CONTAG and high SHEI/SHDI, which indicated high heterogeneity, had a longer growing season. This may be caused by land conversions from agricultural land to developed land such as RE, PF, TR, and IN. Those land conversions increased the varieties of patch types in the transect, thus affecting CONTAG and SHEI/SHDI, but they might not influence PD. The land conversions also enhanced the effects of UHI on vegetation phenology, thus ending up with a longer growing season. In addition, we found inconsistencies in the correlation between both LSI and ED with SOS in different time intervals at the landscape scale. This may be due to the rapid and complicated urbanization process in Shanghai. As described in Li et al. [

37], urban regions in Shanghai were characterized with a complex-shaped (high LSI/ED) landscape at first and then associated with a simpler (low LSI/ED) one later on. Since areas around the urban center always experienced longer LOS compared with rural regions, the correlations between LSI/ED and LOS in 1984–1995 were the opposite to those in 2001–2005.

At the class level, our results suggested land cover composition significantly affected the vegetation phenology. The increase in the percentage of residential land, public facilities, industrial land, and traffic land in a given landscape significantly advanced SOS and delayed EOS, therefore, resulting in longer LOS as these land cover types tended to have higher LST [

38,

55,

56,

57]. The increase of proportion of water and agricultural land, on the other hand, had later SOS and earlier EOS since those lands had lower LST [

38,

55,

56,

57]. More importantly, our results found that vegetation phenology was not only influenced by local land cover composition, but was also influenced by their spatial configuration. Spatial configuration can affect the flow of energy and energy exchange among different land cover types [

53,

58], therefore, altering vegetation phenology. For example, the increase of PD, ED, and LSI of public facility and industrial land leads to an increase of LOS because the increase of edges and patches can lead to the developed land absorbing solar energy more efficiently [

59], thus increasing the LST and lengthening LOS. Meanwhile, the PD and ED of urban vegetation were negatively correlated with LOS because the increase of vegetation edges and patches enhanced energy exchanges and reduced LST, thus resulting in a shorter growing season. Those findings indicate that habitats could be created in urban environment to minimize the effect of UHI on plant phenology so that the phenological mismatch between different trophic levels could be mitigated for migratory bird nesting [

7,

8]. Additionally, we observed inconsistencies of correlations between different phenology metrics and class level landscape metrics. Those inconsistencies could be due to different sensitivities between spring onset and fall senescence to LST [

28,

30].

In addition to the lack of data for validation, this study also has some other limitations. First, we did not take vegetation species composition into account when describing the phenology pattern and its interaction with landscape metrics. Exotic, ornamental, and invasive vegetation species are common in urban landscapes [

60]. The composition of vegetation species with different phenological characteristics can introduce bias in the spatial analysis of phenology patterns. Second, this research cannot disaggregate the effects of climate change from UHI effects as global warming could enhance UHI effects. For example, the temporal changes in

Table 5 were the results of combined effects of climate change and UHI.

6. Conclusions

We derived the mean phenology (SOS, EOS, and LOS) of urban vegetation at 30-m spatial resolution based on multi-year Landsat images along an east-west transect that runs through the center of Shanghai, China during 1984–2015. Landscape composition and configuration metrics along the transect were derived from high spatial resolution aerial photos. We found that (1) average SOS of urban vegetation occurred 5–10 days earlier and EOS appeared 5–11 days later, causing LOS longer about 10–21 days in urban center compared with those of the rural counterparts. (2) Based on the statistics of the standardized anomalies across five time periods, 12.6% of the urban vegetation in the transect experienced longer growing seasons in the time interval of 1984–1995, while 22.2% experienced longer growing seasons in the time interval of 2011–2015. (3) Urban landscape structure influences the phenology of urban vegetation. At the landscape level, the increase of patch density was associated with later SOS and earlier EOS for urban vegetation, thus, a shorter LOS. At the class scale, increasing the percentage of developed land correlates with advanced spring onset and delayed fall senescence, thus, a longer season, while higher proportions of agricultural land and water led to later SOS, earlier EOS and, thus, shorter LOS. Meanwhile, higher edge density and patch density of developed land had positive effects on LOS, while those of urban vegetation had negative effects on LOS. Those findings revealed that the composition and configuration of urban LCLU significantly influenced the spatial pattern of vegetation phenology.