Remote-Sensing Estimation of Evapotranspiration for Multiple Land Cover Types Based on an Improved Canopy Conductance Model

Highlights

- A new remote-sensing canopy conductance model is developed by physically integrating Jarvis’ multi-factor stress functions with the K95 canopy radiation transfer mechanism, enabling PAR to regulate stomatal conductance through canopy-absorbed radiation rather than as an empirical stress factor.

- Based on observations from 88 global flux sites during 2015–2023, a two-stage optimization strategy differentiated by land cover types is proposed to determine the optimal combination of environmental limiting functions across 12 IGBP land cover types.

- The proposed framework resolves the long-standing inconsistency of Jarvis-type models across heterogeneous ecosystems by introducing radiative constraints into canopy conductance modeling.

- This mechanism-based modeling strategy enhances the physiological and radiative consistency of remote-sensing ET estimation and provides a new pathway for generating large-scale ET products under diverse land cover conditions.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials

2.1. Flux Tower Data

2.2. Photosynthetically Active Radiation Data

2.3. Vegetation Parameter Data

2.4. Soil Moisture Data

2.5. Canopy Height Data

2.6. Meteorological Forcing Data

3. Methods

3.1. Remote-Sensing Algorithms for ET

3.1.1. Vegetation Transpiration

3.1.2. Evaporation from the Wet Canopy Surface

3.1.3. Soil Evaporation

3.2. Improvement of the Canopy Conductance Model

3.3. Model Optimization

4. Results

4.1. Performance of Different Constraint Combinations

4.2. Optimal Constraint Function Selection

4.3. Validation of LE Against Flux Tower Measurements

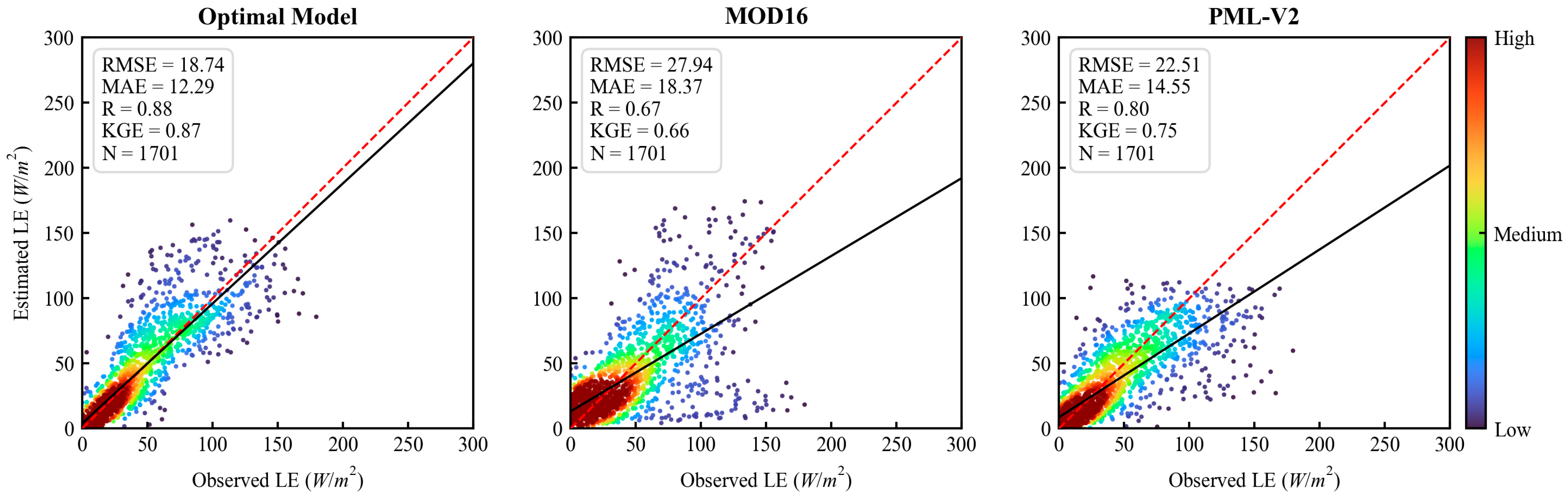

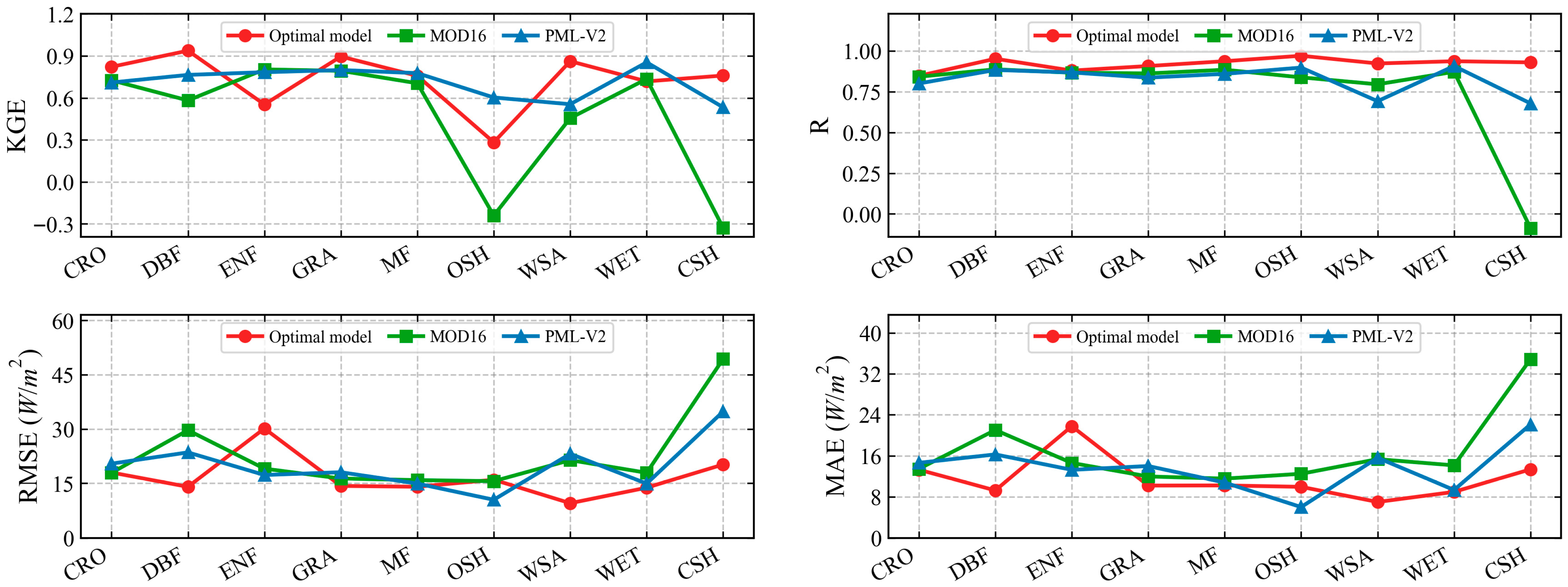

4.3.1. Validation over Optimization Sites

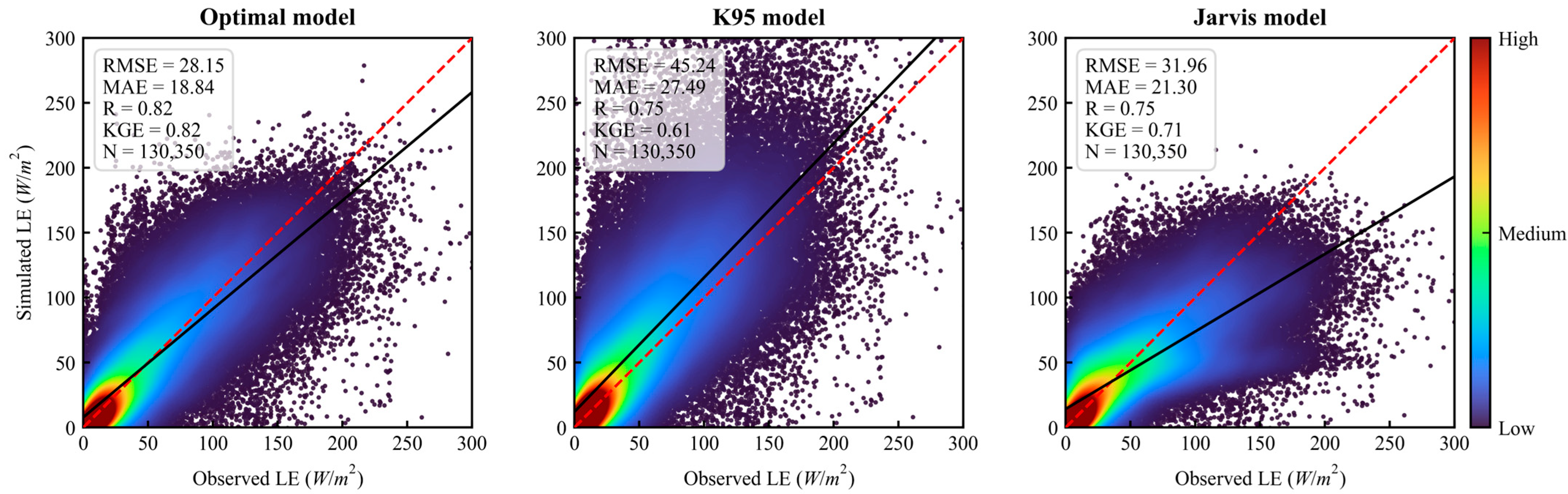

4.3.2. Validation over Holdout Sites

4.4. Comparison with Other ET Products

5. Discussion

5.1. Effects of Canopy Conductance Structural Assumptions on Model Performance

5.2. Coupling Between Temperature and Vapor Pressure Deficit Functions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miralles, D.G.; Gash, J.H.; Holmes, T.R.H.; De Jeu, R.A.M.; Dolman, A.J. Global Canopy Interception from Satellite Observations. J. Geophys. Res. 2010, 115, 2009JD013530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoy, P.C.; El-Madany, T.S.; Fisher, J.B.; Gentine, P.; Gerken, T.; Good, S.P.; Klosterhalfen, A.; Liu, S.; Miralles, D.G.; Perez-Priego, O.; et al. Reviews and Syntheses: Turning the Challenges of Partitioning Ecosystem Evaporation and Transpiration into Opportunities. Biogeosciences 2019, 16, 3747–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhan, C.; Ning, L.; Guo, H. Evaluation of Global Terrestrial Evapotranspiration in CMIP6 Models. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2021, 143, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Peña-Arancibia, J.L.; McVicar, T.R.; Chiew, F.H.S.; Vaze, J.; Liu, C.; Lu, X.; Zheng, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.Y.; et al. Multi-Decadal Trends in Global Terrestrial Evapotranspiration and Its Components. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (Eds.) Crop Evapotranspiration: Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements; FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Miralles, D.G.; Holmes, T.R.H.; De Jeu, R.A.M.; Gash, J.H.; Meesters, A.G.C.A.; Dolman, A.J. Global Land-Surface Evaporation Estimated from Satellite-Based Observations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 15, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-L.; Tang, R.; Wan, Z.; Bi, Y.; Zhou, C.; Tang, B.; Yan, G.; Zhang, X. A Review of Current Methodologies for Regional Evapotranspiration Estimation from Remotely Sensed Data. Sensors 2009, 9, 3801–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Jia, L. Monitoring of Evapotranspiration in a Semi-Arid Inland River Basin by Combining Microwave and Optical Remote Sensing Observations. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 3056–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Jia, L.; Hu, G. Global Land Surface Evapotranspiration Monitoring by ETMonitor Model Driven by Multi-Source Satellite Earth Observations. J. Hydrol. 2022, 613, 128444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastiaanssen, W.G.M.; Menenti, M.; Feddes, R.A.; Holtslag, A.A.M. A Remote Sensing Surface Energy Balance Algorithm for Land (SEBAL). 1. Formulation. J. Hydrol. 1998, 212–213, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z. The Surface Energy Balance System (SEBS) for Estimation of Turbulent Heat Fluxes. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2002, 6, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteith, J.L. Evaporation and Environment. Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 1965, 19, 205–234. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, D.; Jiménez, C.; Miralles, D.G.; Jung, M.; Hirschi, M.; Ershadi, A.; Martens, B.; McCabe, M.F.; Fisher, J.B.; Mu, Q.; et al. The WACMOS-ET Project—Part 1: Tower-Scale Evaluation of Four Remote-Sensing-Based Evapotranspiration Algorithms. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 20, 803–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.; Longuevergne, L.; Scanlon, B.R. Global Analysis of Approaches for Deriving Total Water Storage Changes from GRACE Satellites. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 2574–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Kimball, J.S.; Running, S.W. A Review of Remote Sensing Based Actual Evapotranspiration Estimation. WIREs Water 2016, 3, 834–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerosa, G.; Mereu, S.; Finco, A.; Marzuoli, R. Stomatal Conductance Modeling to Estimate the Evapotranspiration of Natural and Agricultural Ecosystems. In Evapotranspiration—Remote Sensing and Modeling; Irmak, A., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, S.; Pan, N.; Tian, H.; Friedlingstein, P.; Sitch, S.; Shi, H.; Arora, V.K.; Haverd, V.; Jain, A.K.; Kato, E.; et al. Evaluation of Global Terrestrial Evapotranspiration Using State-of-the-Art Approaches in Remote Sensing, Machine Learning and Land Surface Modeling. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 24, 1485–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, T.N. Modeling Stomatal Conductance. Plant Physiol. 2017, 174, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medlyn, B.E.; Duursma, R.A.; Eamus, D.; Ellsworth, D.S.; Prentice, I.C.; Barton, C.V.M.; Crous, K.Y.; De Angelis, P.; Freeman, M.; Wingate, L. Reconciling the Optimal and Empirical Approaches to Modelling Stomatal Conductance: RECONCILING OPTIMAL AND EMPIRICAL STOMATAL MODELS. Glob. Change Biol. 2011, 17, 2134–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, P.G. The Interpretation of the Variations in Leaf Water Potential and Stomatal Conductance Found in Canopies in the Field. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. B Biol. Sci. 1976, 273, 593–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Yao, F.; Magliulo, V. A Remote Sensing-Based Two-Leaf Canopy Conductance Model: Global Optimization and Applications in Modeling Gross Primary Productivity and Evapotranspiration of Crops. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 215, 411–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lhomme, J.-P. Stomatal Control of Transpiration: Examination of the Jarvis-type Representation of Canopy Resistance in Relation to Humidity. Water Resour. Res. 2001, 37, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, J.T.; Woodrow, I.E.; Berry, J.A. A Model Predicting Stomatal Conductance and Its Contribution to the Control of Photosynthesis under Different Environmental Conditions. In Progress in Photosynthesis Research; Biggins, J., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1987; pp. 221–224. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, T.N.; Mott, K.A. Modelling Stomatal Conductance in Response to Environmental Factors. Plant Cell Environ. 2013, 36, 1691–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, J.; Gan, G.; Chen, J.; Su, Y.; García, M.; Gao, Y. Biophysical Constraints on Evapotranspiration Partitioning for a Conductance-Based Two Source Energy Balance Model. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 127179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, P.; Cai, C. Applicability Evaluation of Soil Moisture Constraint Algorithms in Remote Sensing Evapotranspiration Models. J. Hydrol. 2023, 623, 129870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Meng, D.; Chen, X.; Li, X. Validation and Comparison of Seven Land Surface Evapotranspiration Products in the Haihe River Basin, China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Li, M.; Su, Y.; Gao, H.; Vlček, L. A Modified Jarvis Model to Improve the Expressing of Stomatal Response in a Beech Forest. Hydrol. Process. 2023, 37, e14955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelliher, F.M.; Leuning, R.; Raupach, M.R.; Schulze, E.-D. Maximum Conductances for Evaporation from Global Vegetation Types. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1995, 73, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, P.J.; Dickinson, R.E.; Randall, D.A.; Betts, A.K.; Hall, F.G.; Berry, J.A.; Collatz, G.J.; Denning, A.S.; Mooney, H.A.; Nobre, C.A.; et al. Modeling the Exchanges of Energy, Water, and Carbon Between Continents and the Atmosphere. Science 1997, 275, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Q.; Heinsch, F.A.; Zhao, M.; Running, S.W. Development of a Global Evapotranspiration Algorithm Based on MODIS and Global Meteorology Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2007, 111, 519–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Q.; Zhao, M.; Running, S.W. Improvements to a MODIS Global Terrestrial Evapotranspiration Algorithm. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 1781–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonan, G.B.; Williams, M.; Fisher, R.A.; Oleson, K.W. Modeling Stomatal Conductance in the Earth System: Linking Leaf Water-Use Efficiency and Water Transport along the Soil–Plant–Atmosphere Continuum. Geosci. Model Dev. 2014, 7, 2193–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Dickinson, R.E. A Review of Global Terrestrial Evapotranspiration: Observation, Modeling, Climatology, and Climatic Variability. Rev. Geophys. 2012, 50, 2011RG000373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kauwe, M.G.; Medlyn, B.E.; Zaehle, S.; Walker, A.P.; Dietze, M.C.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Jain, A.K.; El-Masri, B.; Hickler, T.; et al. Where Does the Carbon Go? A Model–Data Intercomparison of Vegetation Carbon Allocation and Turnover Processes at Two Temperate Forest Free-air CO2 Enrichment Sites. N. Phytol. 2014, 203, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonan, G.B.; Doney, S.C. Climate, Ecosystems, and Planetary Futures: The Challenge to Predict Life in Earth System Models. Science 2018, 359, eaam8328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, B.; Miralles, D.G.; Lievens, H.; Van Der Schalie, R.; De Jeu, R.A.M.; Férnandez-Prieto, D.; Beck, H.E.; Dorigo, W.A.; Verhoest, N.E.C. GLEAM v3: Satellite-Based Land Evaporation and Root-Zone Soil Moisture. Geosci. Model Dev. 2017, 10, 1903–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knauer, J.; Zaehle, S.; Medlyn, B.E.; Reichstein, M.; Williams, C.A.; Migliavacca, M.; De Kauwe, M.G.; Werner, C.; Keitel, C.; Kolari, P.; et al. Towards Physiologically Meaningful Water-use Efficiency Estimates from Eddy Covariance Data. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 694–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restrepo-Coupe, N.; Da Rocha, H.R.; Hutyra, L.R.; Da Araujo, A.C.; Borma, L.S.; Christoffersen, B.; Cabral, O.M.R.; De Camargo, P.B.; Cardoso, F.L.; Da Costa, A.C.L.; et al. What Drives the Seasonality of Photosynthesis across the Amazon Basin? A Cross-Site Analysis of Eddy Flux Tower Measurements from the Brasil Flux Network. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 182–183, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorello, G.; Trotta, C.; Canfora, E.; Chu, H.; Christianson, D.; Cheah, Y.-W.; Poindexter, C.; Chen, J.; Elbashandy, A.; Humphrey, M.; et al. The FLUXNET2015 Dataset and the ONEFlux Processing Pipeline for Eddy Covariance Data. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Wang, J.; Weiss, M.; Myneni, R.B. A High-Quality Reprocessed MODIS Leaf Area Index Dataset (HiQ-LAI). 2023. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/8296768 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Chen, J.; Jönsson, P.; Tamura, M.; Gu, Z.; Matsushita, B.; Eklundh, L. A Simple Method for Reconstructing a High-Quality NDVI Time-Series Data Set Based on the Savitzky–Golay Filter. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 91, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichle, R.H.; De Lannoy, G.J.M.; Liu, Q.; Ardizzone, J.V.; Colliander, A.; Conaty, A.; Crow, W.; Jackson, T.J.; Jones, L.A.; Kimball, J.S.; et al. Assessment of the SMAP Level-4 Surface and Root-Zone Soil Moisture Product Using In Situ Measurements. J. Hydrometeorol. 2017, 18, 2621–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Schaap, M.G.; Wei, Z. Development of Hierarchical Ensemble Model and Estimates of Soil Water Retention with Global Coverage. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2020GL088819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Su, Z.; Ma, Y.; Yang, K.; Wang, B. Estimation of Surface Energy Fluxes under Complex Terrain of Mt. Qomolangma over the Tibetan Plateau. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 17, 1607–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.B.; Tu, K.P.; Baldocchi, D.D. Global Estimates of the Land–Atmosphere Water Flux Based on Monthly AVHRR and ISLSCP-II Data, Validated at 16 FLUXNET Sites. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 901–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Wang, S.Q.; Billesbach, D.; Oechel, W.; Zhang, J.H.; Meyers, T.; Martin, T.A.; Matamala, R.; Baldocchi, D.; Bohrer, G.; et al. Global Estimation of Evapotranspiration Using a Leaf Area Index-Based Surface Energy and Water Balance Model. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 124, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdy, A.J.; Fisher, J.B.; Goulden, M.L.; Colliander, A.; Halverson, G.; Tu, K.; Famiglietti, J.S. SMAP Soil Moisture Improves Global Evapotranspiration. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 219, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massman, W.J. A Model Study of kBH−1 for Vegetated Surfaces Using ‘Localized near-Field’ Lagrangian Theory. J. Hydrol. 1999, 223, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindroth, A.; Mölder, M.; Lagergren, F. Heat Storage in Forest Biomass Improves Energy Balance Closure. Biogeosciences 2010, 7, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moderow, U.; Aubinet, M.; Feigenwinter, C.; Kolle, O.; Lindroth, A.; Mölder, M.; Montagnani, L.; Rebmann, C.; Bernhofer, C. Available Energy and Energy Balance Closure at Four Coniferous Forest Sites across Europe. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2009, 98, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Leuning, R.; Hutley, L.B.; Beringer, J.; McHugh, I.; Walker, J.P. Using Long-term Water Balances to Parameterize Surface Conductances and Calculate Evaporation at 0.05° Spatial Resolution. Water Resour. Res. 2010, 46, 2009WR008716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gutiérrez, V.; Stöckle, C.; Gil, P.M.; Meza, F.J. Evaluation of Penman-Monteith Model Based on Sentinel-2 Data for the Estimation of Actual Evapotranspiration in Vineyards. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Su, Z.; Ma, Y.; Trigo, I.; Gentine, P. Remote Sensing of Global Daily Evapotranspiration Based on a Surface Energy Balance Method and Reanalysis Data. JGR Atmos. 2021, 126, e2020JD032873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehr, R.; Saleska, S.R. Calculating Canopy Stomatal Conductance from Eddy Covariance Measurements, in Light of the Energy Budget Closure Problem. Biogeosciences 2021, 18, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flo, V.; Martínez-Vilalta, J.; Granda, V.; Mencuccini, M.; Poyatos, R. Vapour Pressure Deficit Is the Main Driver of Tree Canopy Conductance across Biomes. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 322, 109029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.-Q.; Jia, J.-B.; Yan, W.-D.; Hu, L.; Wang, Y.-F.; Chen, Y. Characteristics of Canopy Conductance and Environmental Driving Mechanism in Three Monsoon Climate Regions of China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 935926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuning, R.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Rajaud, A.; Cleugh, H.; Tu, K. A Simple Surface Conductance Model to Estimate Regional Evaporation Using MODIS Leaf Area Index and the Penman-Monteith Equation. Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44, 2007WR006562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossiord, C.; Buckley, T.N.; Cernusak, L.A.; Novick, K.A.; Poulter, B.; Siegwolf, R.T.W.; Sperry, J.S.; McDowell, N.G. Plant Responses to Rising Vapor Pressure Deficit. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 1550–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slot, M.; Rifai, S.W.; Eze, C.E.; Winter, K. The Stomatal Response to Vapor Pressure Deficit Drives the Apparent Temperature Response of Photosynthesis in Tropical Forests. New Phytol. 2024, 244, 1238–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wedegaertner, K.; Shekoofa, A.; Purdom, S.; Walters, K.; Duncan, L.; Raper, T.B. Cotton Stomatal Closure under Varying Temperature and Vapor Pressure Deficit, Correlation with the Hydraulic Conductance Trait. J. Cotton Res. 2022, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anav, A.; Proietti, C.; Menut, L.; Carnicelli, S.; De Marco, A.; Paoletti, E. Sensitivity of Stomatal Conductance to Soil Moisture: Implications for Tropospheric Ozone. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 5747–5763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.D.; Gu, L.; Hanson, P.J.; Frankenberg, C.; Sack, L. The Ecosystem Wilting Point Defines Drought Response and Recovery of a quercus-carya Forest. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 2015–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Farias, S.; Poblete-Echeverría, C.; Brisson, N. Parameterization of a Two-Layer Model for Estimating Vineyard Evapotranspiration Using Meteorological Measurements. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2010, 150, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, S.; Mackay, D.S.; Clayton, M.K.; Kruger, E.L.; Ewers, B.E. Bayesian Analysis for Uncertainty Estimation of a Canopy Transpiration Model. Water Resour. Res. 2007, 43, 2006WR005028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kang, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, F.; Hao, X.; Ortega-Farias, S.; Guo, W.; Ji, S.; Wang, J.; Jiang, X. Quantifying the Combined Effects of Climatic, Crop and Soil Factors on Surface Resistance in a Maize Field. J. Hydrol. 2013, 489, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Kang, S.; Du, T.; Hao, X.; Tong, L. Modeling Crop Water Use in an Irrigated Maize Cropland Using a Biophysical Process-Based Model. J. Hydrol. 2015, 529, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.V.; Kling, H.; Yilmaz, K.K.; Martinez, G.F. Decomposition of the Mean Squared Error and NSE Performance Criteria: Implications for Improving Hydrological Modelling. J. Hydrol. 2009, 377, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, C. Leaf Diffusive Conductances in the Major Vegetation Types of the Globe. In Ecophysiology of Photosynthesis; Schulze, E.-D., Caldwell, M.M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995; pp. 463–490. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, K.; Goldstein, A.; Falge, E.; Aubinet, M.; Baldocchi, D.; Berbigier, P.; Bernhofer, C.; Ceulemans, R.; Dolman, H.; Field, C.; et al. Energy Balance Closure at FLUXNET Sites. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2002, 113, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauder, M.; Foken, T.; Cuxart, J. Surface-Energy-Balance Closure over Land: A Review. Bound. Layer Meteorol. 2020, 177, 395–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Li, A. A Review on Land Surface Processes Modelling over Complex Terrain. Adv. Meteorol. 2015, 2015, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overgaard, J.; Rosbjerg, D.; Butts, M.B. Land-Surface Modelling in Hydrological Perspective—A Review. Biogeosciences 2006, 3, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Sharma, P. A Review of Machine Learning Applications in Land Surface Modeling. Earth 2021, 2, 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, S.; Lymburn, T.; Stemler, T.; Sun, Y.; Small, M. Model Calibration and Validation from a Statistical Inference Perspective. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.08562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, S.; Kuenzer, C.; Gessner, U.; Klein, I.; Rutzinger, M. Validation of Earth Observation Time-Series: A Review for Large-Area and Temporally Dense Land Surface Products. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kong, D.; Gan, R.; Chiew, F.H.S.; McVicar, T.R.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, Y. Coupled Estimation of 500 m and 8-Day Resolution Global Evapotranspiration and Gross Primary Production in 2002–2017. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 222, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuning, R. A Critical Appraisal of a Combined Stomatal-photosynthesis Model for C3 Plants. Plant Cell Environ. 1995, 18, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-P.; Leuning, R. A Two-Leaf Model for Canopy Conductance, Photosynthesis and Partitioning of Available Energy I:: Model Description and Comparison with a Multi-Layered Model. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1998, 91, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Lamb, D.W.; Warwick, N.W.M. A Canopy Transpiration Model Based on Scaling Up Stomatal Conductance and Radiation Interception as Affected by Leaf Area Index. Water 2021, 13, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Duursma, R.A.; De Kauwe, M.G.; Kumarathunge, D.; Jiang, M.; Mahmud, K.; Gimeno, T.E.; Crous, K.Y.; Ellsworth, D.S.; Peters, J.; et al. Incorporating Non-Stomatal Limitation Improves the Performance of Leaf and Canopy Models at High Vapour Pressure Deficit. Tree Physiol. 2019, 39, 1961–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, C.E.; Winter, K.; Slot, M. Vapor-Pressure-Deficit-Controlled Temperature Response of Photosynthesis in Tropical Trees. Photosynthetica 2024, 62, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.; Way, D.A.; Sadok, W. Systemic Effects of Rising Atmospheric Vapor Pressure Deficit on Plant Physiology and Productivity. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 1704–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchin, R.M.; Medlyn, B.E.; Tjoelker, M.G.; Ellsworth, D.S. Decoupling Between Stomatal Conductance and Photosynthesis Occurs under Extreme Heat in Broadleaf Tree Species Regardless of Water Access. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 6319–6335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constraint Function | Letter | Parameter | Description | Bound | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | a | Air temperature when f(T) equals 0 | −10–0 | Zheng et al. [9] | |

| b | Air temperature when f(T) equals 1 | 20–30 | |||

| c | Air temperature when f(T) equals 0 | 30–40 | |||

| T2 | d | Empirical coefficient | 0–0.005 | Ortega-Farias et al. [64] | |

| e | Empirical coefficient | 0–50 | |||

| V1 | VPD when is half its maximum value | 0.3–5 | Samanta et al. [65] | ||

| V2 | m | Empirical coefficient | 0–1 | Li et al. [66] | |

| V3 | n | Empirical coefficient | 0–0.5 | Samanta et al. [65] | |

| W1 | x | Empirical coefficient | 0.01–2 | Preliminary calculation | |

| W2 | Wilting point | - | ESWRGC dataset | ||

| Field capacity | - | ||||

| W3 | y | Empirical coefficient | 0.1–5 | Ding et al. [67] |

| IGBP Class | Optimal Model | KGE | R | RMSE | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENF | M221 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 30.1 | 19.6 |

| EBF | M231 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 28.5 | 20.9 |

| DNF | M221 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 15.6 | 11.6 |

| DBF | M231 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 27.4 | 17.9 |

| MF | M231 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 18.8 | 13.1 |

| CRO | M231 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 31.1 | 21.6 |

| GRA | M231 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 30.5 | 20.8 |

| OSH | M221 | 0.68 | 0.78 | 22.5 | 15.5 |

| CSH | M221 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 22.8 | 16.4 |

| SAV | M221 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 14.9 | 11.0 |

| WSA | M131 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 18.1 | 13.1 |

| WET | M231 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 26.8 | 18.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Xin, X.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, S.; Li, T.; Yu, S. Remote-Sensing Estimation of Evapotranspiration for Multiple Land Cover Types Based on an Improved Canopy Conductance Model. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030513

Wang J, Xin X, Ye Z, Zhang S, Li T, Yu S. Remote-Sensing Estimation of Evapotranspiration for Multiple Land Cover Types Based on an Improved Canopy Conductance Model. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(3):513. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030513

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jianfeng, Xiaozhou Xin, Zhiqiang Ye, Shihao Zhang, Tianci Li, and Shanshan Yu. 2026. "Remote-Sensing Estimation of Evapotranspiration for Multiple Land Cover Types Based on an Improved Canopy Conductance Model" Remote Sensing 18, no. 3: 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030513

APA StyleWang, J., Xin, X., Ye, Z., Zhang, S., Li, T., & Yu, S. (2026). Remote-Sensing Estimation of Evapotranspiration for Multiple Land Cover Types Based on an Improved Canopy Conductance Model. Remote Sensing, 18(3), 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030513