NOAH: A Multi-Modal and Sensor Fusion Dataset for Generative Modeling in Remote Sensing

Highlights

- This research produced a multimodal and sensor fusion dataset (NOAH) to be used by researchers for Generative Modeling of soft sensors to generate synthetic “Point -> Region” data.

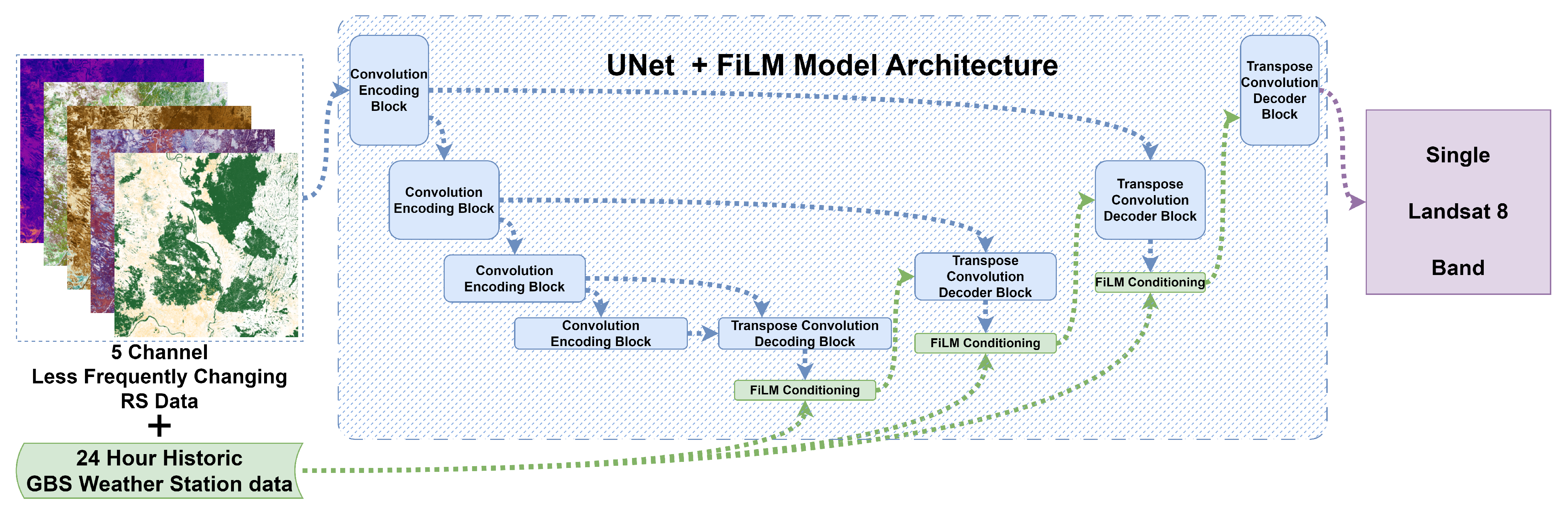

- The research showed the ability of the FiLM+UNet model to generate synthetic data for TIR and Cirrus bands.

- Model-generated or synthetic data can be produced for hypothetical climate change scenarios by varying the ground-based sensor values.

- Using nearby point ground-based sensor data, missing data for a region can be produced

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Ideal Dataset Requirements for Remote Sensing Soft Sensors with Generative Modeling

- 1.

- Non-Simulated Data: Real-world data exhibit imperfections which are not easily reconstructed in simulation, making transfer learning from synthetic to real data a nontrivial task [47]. This, although stated for a 3D object, is true for RS data as well. The simulated data may provide more training data, yet there may be bias or missing imperfections in the data that is being simulated. When this data is used for training models or to apply transfer learning, the models trained will incorporate these inconsistencies. Hence, an ideal dataset for GM of RS should not have simulated data.

- 2.

- Large Dataset Size: The dataset should be significantly large, since deep learning approaches need more data for training. An improvement in prediction performance with increasing magnitude of the dataset size was found in [48]. Novel approaches and foundational model training especially need a large dataset size.

- 3.

- Multi-Modal Dataset: EO data obtained from RS satellites typically has missing data due to cloud cover. Cloud cover on average accounts for 68% of surface data each day [25]. Hence, data from different modalities will be needed to find suitable ways of filling in missing values. Further, validation of data collected from RS sources requires in-situ measurements from ground sensors.

- 4.

- Sensor Fusion Datasets: Multiple sensor types together give a holistic picture of the environment being measured. For example, in Landsat 8 and 9, TIR and OLI sensors are used to get 11 bands of data [35].

- 5.

- Large Temporal Coverage: More than 96% of the land cover of Canada remains unchanged over a period of 10 years [49]. Hence, to incorporate large-scale and small-scale changes in the dataset, it should have a temporal coverage of either a few years or decades.

- 6.

- Large Coverage Region: Let us consider that the dataset is for a specific forest/region with its distinct climate, soil and forestry. Then models trained on such a dataset will be biased to the region and may not be generalizable to other regions.

- 7.

- Large Tile Area: Data collected from RS sources are corrected and validated using GBS. When data is collated from multiple different types of GBS, which are controlled and operated by various organizations, the GBS distribution is uneven across regions. Hence, it would be ideal to have a large tile area to account for multiple unevenly distributed GBS covered in a single tile.

- 8.

- Low Temporal Resolution: The local changes, such as temperature, rain, wind speed, and wind direction, change more frequently, in a matter of minutes or hours. Hence, farmers relying on this data will need up-to-date information [34]. In case of an ongoing disaster, near-real-time information about the surroundings is vital. Therefore, lower temporal resolution is better.

- 9.

- Fine Spatial Resolution: There are more small fires (area burned ≤ 2 km2) than large fires [26]. Consider an RS satellite has a spatial resolution of 1 km, then it will cover an area of 1 km2. This means that at max 2 pixels in the RS data product will have all of the information of the wildfire. This may not be enough information to model fire spread, as it will be at max 1 additional pixel. Similarly, for other natural disasters as well, it would be recommended to have fine spatial resolution. Additionally, if we have fine spatial resolution, we can build models that can be trained to super-resolution existing coarse-resolution data products.

2.2. Multi-Modal Remote Sensing Dataset

2.3. Sensor Fusion Remote Sensing Dataset

2.4. Comparison of Datasets

3. Now Observation Assemble Horizon (NOAH) Dataset

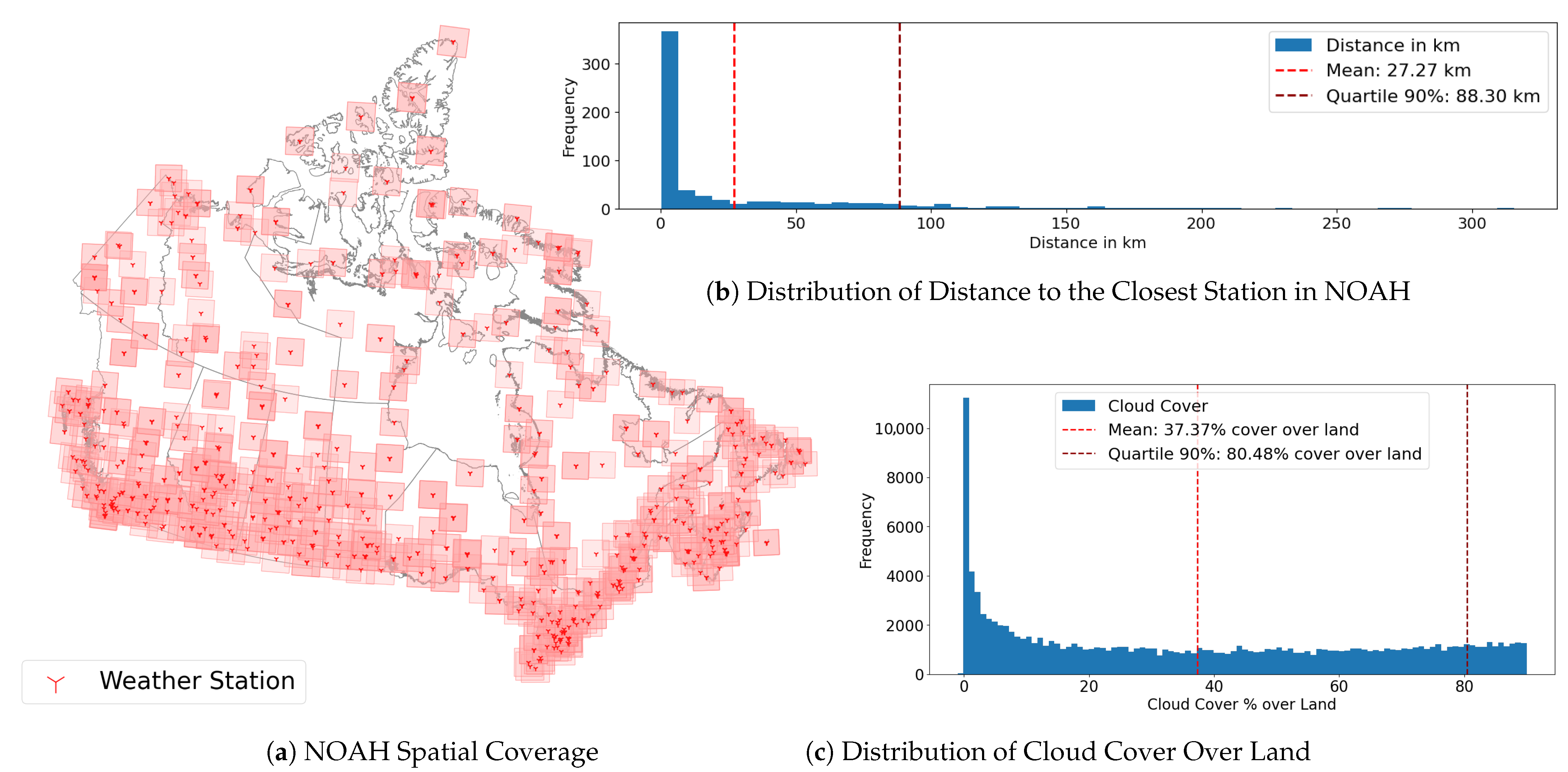

3.1. Region of Interest

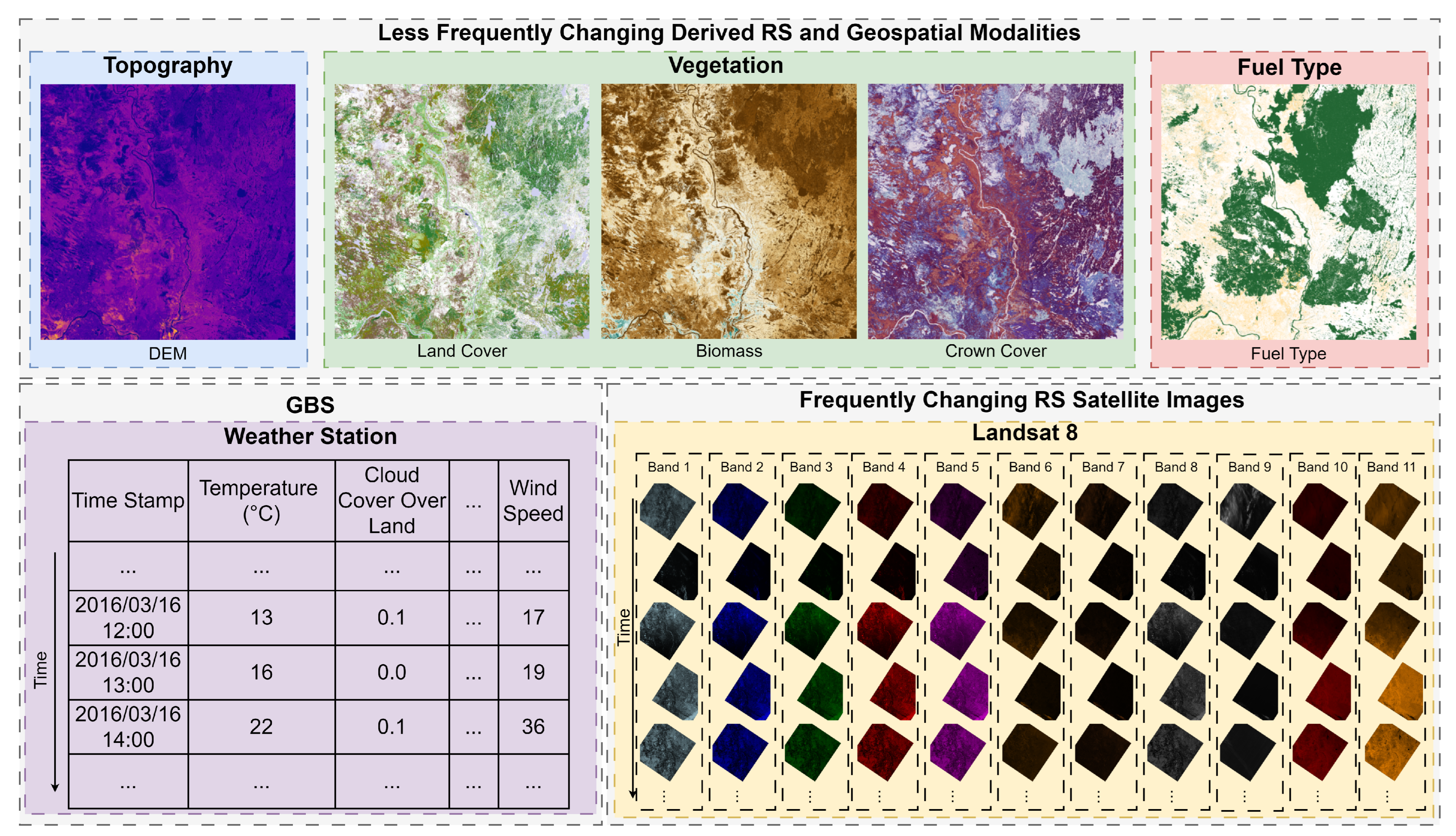

3.2. Modalities of Data

3.2.1. Topography

3.2.2. Vegetation

3.2.3. Fuel Types

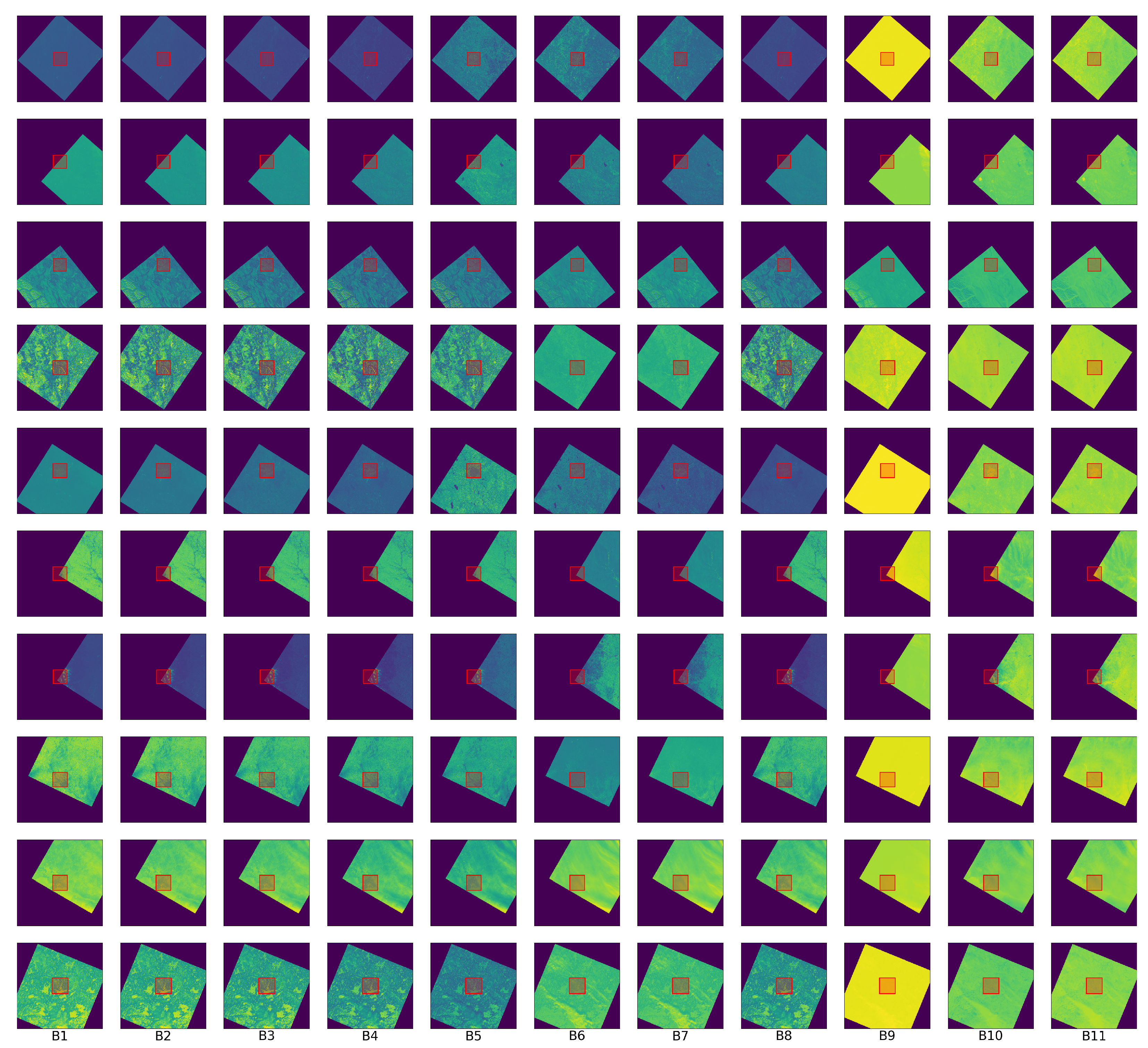

3.2.4. Satellite Imagery

3.2.5. Ground-Based Sensors

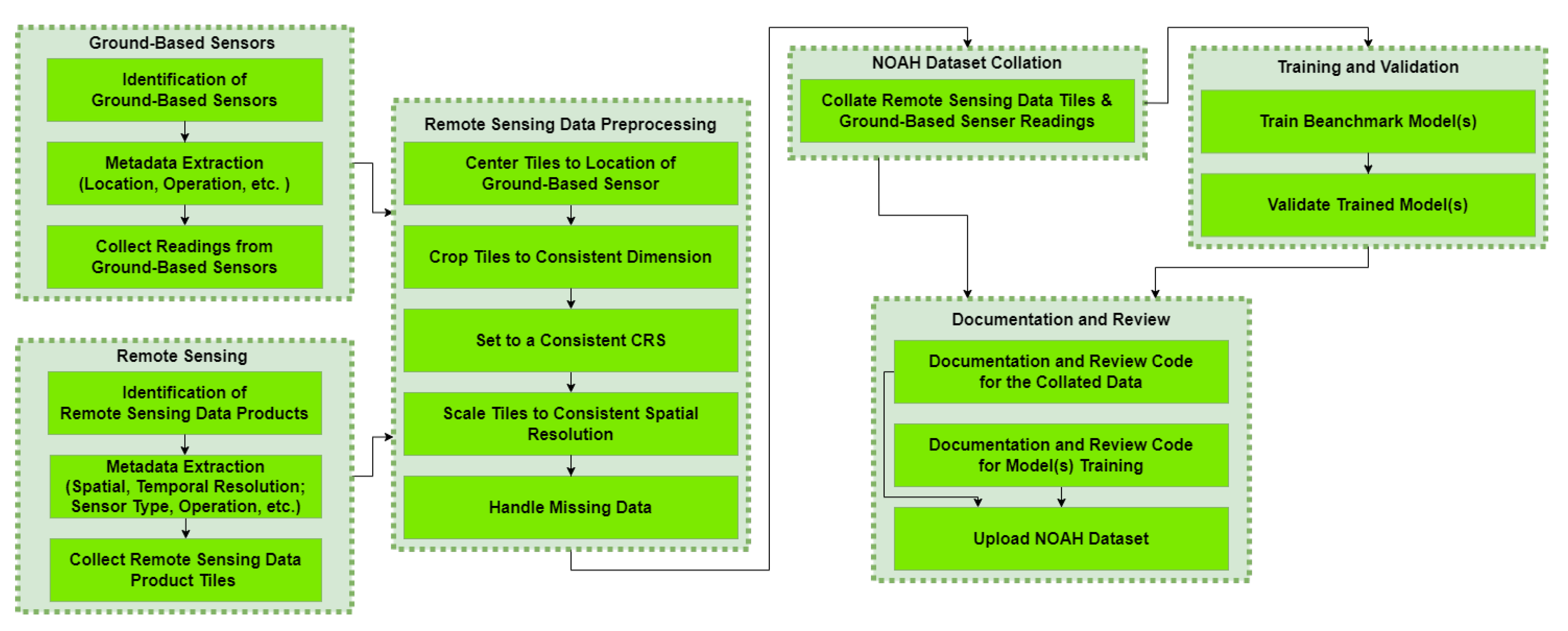

3.3. Dataset Collation Workflow

3.4. Future Dataset Growth Potential

3.5. NOAH Mini

4. Experimentation

4.1. Baseline Modeling and Hyperparameter

4.2. Modeling Metrics

4.2.1. Mean Squared Error

4.2.2. Structural Similarity Index Measure

4.2.3. Peak Signal to Noise Ratio

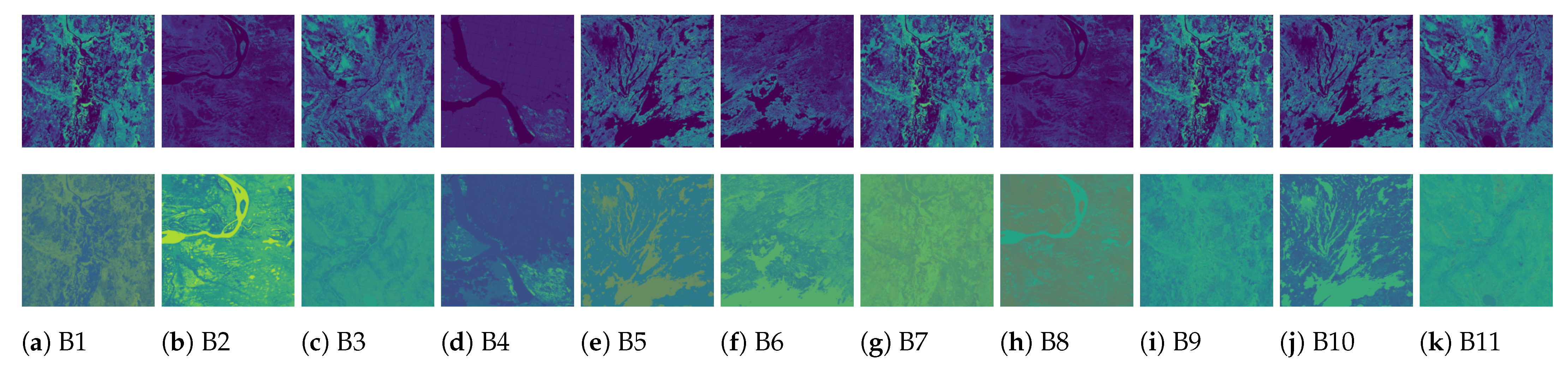

4.3. Benchmark Results

4.4. Ablation Study Results

5. Discussion

- (i)

- Training multi-modal sensor fusion foundational models with in-situ and RS data.

- (ii)

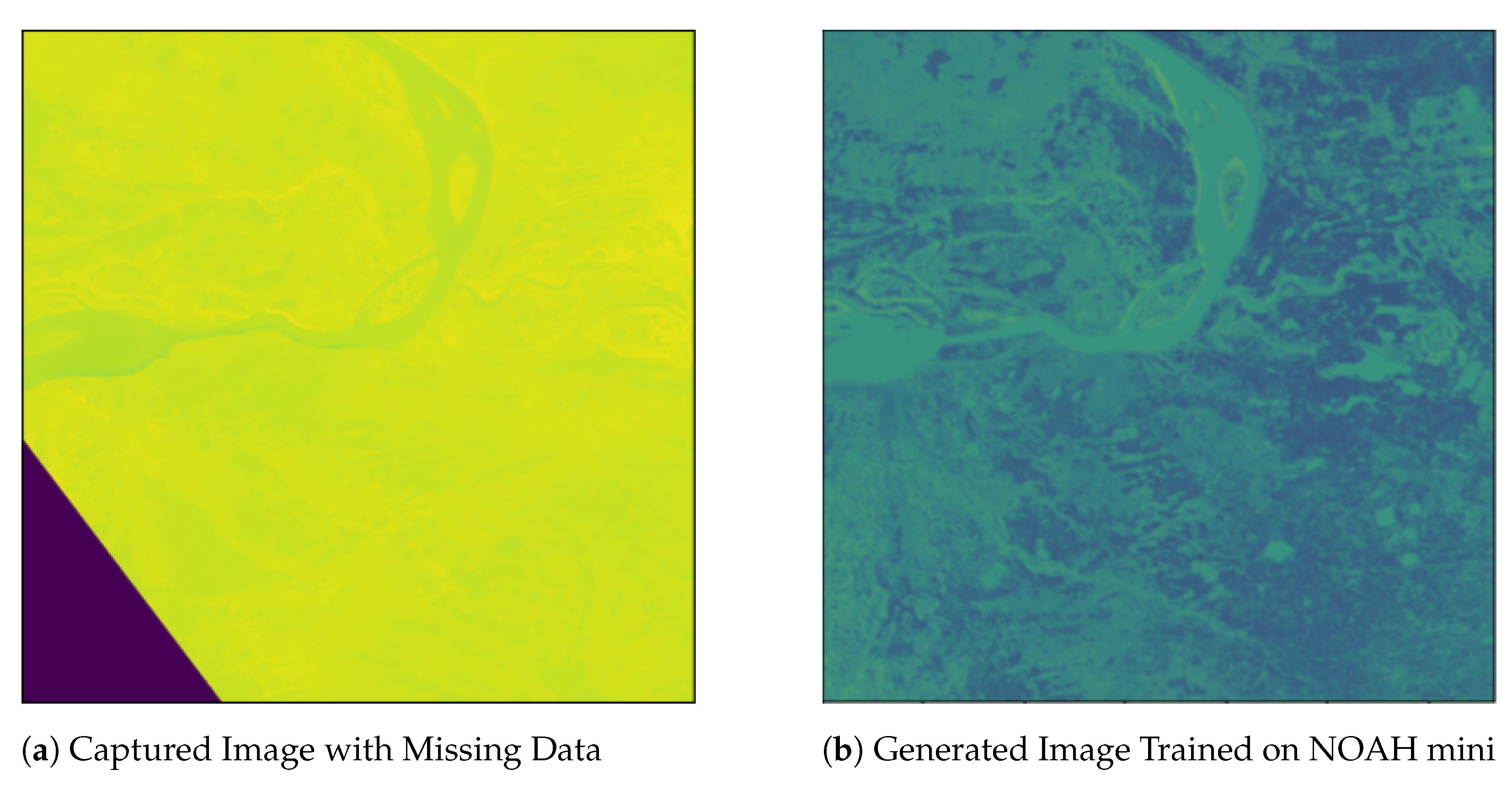

- Expanding existing Landsat 8 or 9 data tiles to get higher coverage: Most Landsat tiles produced by USGS and NASA are not perfect squares. GM, as demonstrated in this research, will be able to expand the existing tile data to get higher coverage. An example of expanding existing data can be seen in Figure 7, where the missing data in the lower left corner of Figure 7a was filled in by the respective band model of UNet + FiLM architecture. The model-generated or synthetic filled-in output can be seen in Figure 7b. GM can also provide the ability to produce model-generated or synthetic missing data when multiple tiles are combined.

- (iii)

- Filling in missing data due to cloud cover with sensor fusion from GBS source: Similar to how band data can be expanded, GM using sensor fusion from GBS source can be applied to the tiles masked with cloud cover to produce model-generated or synthetic missing data.

- (iv)

- Generation of near-real-time data for lacking RS coverage during times of disaster: Sun synchronous satellites do not have near-real-time coverage for all locations. Using GM, we can expand the existing data of nearby regions to cover the regions where disasters like wildfires occur to produce model-generated or synthetic information such as surface temperature and weather.

- (v)

- Generate new hypothetical satellite band data by varying in-situ measurements to see the impact of climate change: As seen from Table 2, bands B9, B10, and B11 produce better model-generated or synthetic data capability using multi-modal sensor fusion. Since in-situ measurements from GBS are provided as input to the model in the form of GBS data, one can vary the input of GBS value to see the resulting hypothetical change in generated output surface temperature and weather values. It should be noted that varying GBS inputs produce model-consistent hypothetical scenarios, not physically based climate simulations. The model-generated or synthetic data from varying GBS can then be applied to visualize climate change using GM or GenAI.

- (vi)

- Generate super-resolution models: Since the NOAH dataset uses fine spatial resolution images, prospective researchers can train super-resolution models by providing a down-sampled NOAH satellite image modality as input to the model during training and have the model predict the fine spatial resolution NOAH satellite image modality.

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRS | Coordinate Reference System |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| ECCC | Environment and Climate Change Canada |

| EO | Earth Observation |

| FiLM | Feature-wise Linear Modulation |

| FoV | Field of View |

| GBS | Ground-Based Sensor |

| GEE | Google Earth Engine |

| GenAI | Generative Artificial Intelligence |

| GM | Generative Modeling |

| LST | Land Surface Temperature |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NOAH | Now Observation Assemble Horizon |

| OLI | Operational Land Imager |

| PSNR | Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| RS | Remote Sensing |

| SAR | Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| SCANFI | Spatialized CAnadian National Forest Inventory |

| SM | Soil Moisture |

| SSIM | Structural Similarity Index Measure |

| TIR | Thermal InfraRed |

| UN | United Nations |

| USGS | United States Geological Survey |

| WMO | World Meteorological Organization |

References

- Ma, R.H.; Wang, Y.H.; Lee, C.Y. Wireless Remote Weather Monitoring System Based on MEMS Technologies. Sensors 2011, 11, 2715–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thies, B.; Bendix, J. Satellite based remote sensing of weather and climate: Recent achievements and future perspectives. Meteorol. Appl. 2011, 18, 262–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmude, J.; Roy, S.; Trojak, W.; Jakubik, J.; Civitarese, D.S.; Singh, S.; Kuehnert, J.; Ankur, K.; Gupta, A.; Phillips, C.E.; et al. Prithvi wxc: Foundation model for weather and climate. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.13598. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Xie, Y.; Jia, X.; Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z. SolarCube: An Integrative Benchmark Dataset Harnessing Satellite and In-situ Observations for Large-Scale Solar Energy Forecasting. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024; pp. 3499–3513. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2024/file/06477eb61ea6b85c6608d42a222462df-Paper-Datasets_and_Benchmarks_Track.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Mitra, A.K. Use of Remote Sensing in Weather and Climate Forecasts. In Social and Economic Impact of Earth Sciences; Gahalaut, V.K., Rajeevan, M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Bieker, J.; Arcucci, R.; Quilodran-Casas, C. Data Assimilation using ERA5, ASOS, and the U-STN Model for Weather Forecasting over the UK. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2023 Workshop on Tackling Climate Change with Machine Learning, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023; Available online: https://www.climatechange.ai/papers/neurips2023/61 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Ashkboos, S.; Huang, L.; Dryden, N.; Ben-Nun, T.; Dueben, P.; Gianinazzi, L.; Kummer, L.; Hoefler, T. ENS-10: A Dataset For Post-Processing Ensemble Weather Forecasts. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2022; pp. 21974–21987. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2022/file/89e44582fd28ddfea1ea4dcb0ebbf4b0-Paper-Datasets_and_Benchmarks.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Oskarsson, J.; Landelius, T.; Lindsten, F. Graph-based Neural Weather Prediction for Limited Area Modeling. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2023 Workshop on Tackling Climate Change with Machine Learning, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Perrakis, D.D.; Cruz, M.; Alexander, M.; Hanes, C.; Thompson, D.; Taylor, S.; Stocks, B. Improved Logistic Models of Crown Fire Probability in Canadian Conifer Forests. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2023, 32, 1455–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, L.; Ulivieri, C.; Jahjah, M.; Loret, E. Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques for Natural Disaster Monitoring. In Space Technologies for the Benefit of Human Society and Earth; Olla, P., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 331–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoro, A.; Duarte, L. Chapter 10-The role of satellite remote sensing in natural disaster management. In Nanotechnology-Based Smart Remote Sensing Networks for Disaster Prevention; Denizli, A., Alencar, M.S., Nguyen, T.A., Motaung, D.E., Eds.; Micro and Nano Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, V.; Miura, Y. PreDisM: Pre-Disaster Modelling with CNN Ensembles for At-Risk Communities. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2021 Workshop on Tackling Climate Change with Machine Learning, Online, 6–14 December 2021; Available online: https://www.climatechange.ai/papers/neurips2021/53 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Ballard, T.; Erinjippurath, G.; Cooper, M.W.; Lowrie, C. Widespread Increases in Future Wildfire Risk to Global Forest Carbon Offset Projects Revealed by Explainable AI. In Proceedings of the ICLR 2023 Workshop on Tackling Climate Change with Machine Learning, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Cao, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, X. A review of regional and Global scale Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) mapping products generated from satellite remote sensing. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 206, 311–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perbet, P.; Guindon, L.; Côté, J.F.; Béland, M. Evaluating deep learning methods applied to Landsat time series subsequences to detect and classify boreal forest disturbances events: The challenge of partial and progressive disturbances. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 306, 114107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, R.S.; Johnston, J.M.; Craig, G.; Jennings, S. Airborne Optical and Thermal Remote Sensing for Wildfire Detection and Monitoring. Sensors 2016, 16, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmpoutis, P.; Papaioannou, P.; Dimitropoulos, K.; Grammalidis, N. A Review on Early Forest Fire Detection Systems Using Optical Remote Sensing. Sensors 2020, 20, 6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutakabbir, A.; Lung, C.H.; Ajila, S.A.; Naik, K.; Zaman, M.; Purcell, R.; Sampalli, S.; Ravichandran, T. A Federated Learning Framework based on Spatio-Temporal Agnostic Subsampling (STAS) for Forest Fire Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 48th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC), Osaka, Japan, 2–4 July 2024; pp. 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutakabbir, A.; Lung, C.H.; Ajila, S.A.; Zaman, M.; Naik, K.; Purcell, R.; Sampalli, S. Forest Fire Prediction Using Multi-Source Deep Learning. In Big Data Technologies and Applications BDTA; Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Science, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 555, pp. 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Mutakabbir, A.; Lung, C.H.; Ajila, S.A.; Zaman, M.; Naik, K.; Purcell, R.; Sampalli, S. Spatio-Temporal Agnostic Deep Learning Modeling of Forest Fire Prediction Using Weather Data. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 47th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC), Torino, Italy, 26–30 June 2023; pp. 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutakabbir, A.; Lung, C.H.; Naik, K.; Zaman, M.; Ajila, S.A.; Ravichandran, T.; Purcell, R.; Sampalli, S. Spatio-Temporal Agnostic Sampling for Imbalanced Multivariate Seasonal Time Series Data: A Study on Forest Fires. Sensors 2025, 25, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroujeni, S.P.H.; Razi, A.; Khoshdel, S.; Afghah, F.; Coen, J.L.; O’Neill, L.; Fule, P.; Watts, A.; Kokolakis, N.M.T.; Vamvoudakis, K.G. A Comprehensive Survey of Research towards AI-Enabled Unmanned Aerial Systems in pre-, active-, and post-Wildfire Management. Inf. Fusion 2024, 108, 102369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, D.A.Z.; Qiu, F.; Fan, N.; Sharp, K. Wildfire Mitigation Plans in Power Systems: A Literature Review. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 37, 3540–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuvieco, E.; Aguado, I.; Salas, J.; García, M.; Yebra, M.; Oliva, P. Satellite Remote Sensing Contributions to Wildland Fire Science and Management. Curr. For. Rep. 2020, 6, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.L.; Wu, H.; Duan, S.B.; Zhao, W.; Ren, H.; Liu, X.; Leng, P.; Tang, R.; Ye, X.; Zhu, J.; et al. Satellite Remote Sensing of Global Land Surface Temperature: Definition, Methods, Products, and Applications. Rev. Geophys. 2023, 61, e2022RG000777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natural Resources Canada. Canadian Wildland Fire Information System|Canadian National Fire Database (CNFDB). 2021. Available online: https://cwfis.cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/ha/nfdb (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Mo, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhu, S. A Review of Reconstructing Remotely Sensed Land Surface Temperature under Cloudy Conditions. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszkuta, M. Impact of Cloud Cover on Local Remote Sensing—Piaśnica River Case Study. Oceanol. Hydrobiol. Stud. 2022, 51, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedley, J.; Russell, B.; Randolph, K.; Dierssen, H. A physics-based method for the remote sensing of seagrasses. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 174, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Li, X.; Cheng, Q.; Zeng, C.; Yang, G.; Li, H.; Zhang, L. Missing Information Reconstruction of Remote Sensing Data: A Technical Review. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2015, 3, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.; Ranchin, T.; Wald, L.; Chanussot, J. Synthesis of Multispectral Images to High Spatial Resolution: A Critical Review of Fusion Methods Based on Remote Sensing Physics. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2008, 46, 1301–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebel, P.; Xu, Y.; Schmitt, M.; Zhu, X.X. SEN12MS-CR-TS: A Remote-Sensing Data Set for Multimodal Multitemporal Cloud Removal. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5222414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zi, Y.; Xie, F.; Song, X.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, H. Thin Cloud Removal for Remote Sensing Images Using a Physical-Model-Based CycleGAN with Unpaired Data. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 1004605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deznabi, I.; Kumar, P.; Fiterau, M. Zero-Shot Microclimate Prediction with Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2023 Workshop on Tackling Climate Change with Machine Learning, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023; Available online: https://www.climatechange.ai/papers/neurips2023/41 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Landsat 8 OLI/TIRS Collection 2 Level-2 Data; Accessed via Google Earth Engine (LANDSAT/LC08/C02/T1), 2020. Available online: https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/LANDSAT_LC08_C02_T1 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Guindon, L.; Manka, F.; Correia, D.L.; Villemaire, P.; Smiley, B.; Bernier, P.; Gauthier, S.; Beaudoin, A.; Boucher, J.; Boulanger, Y. A new approach for spatializing the Canadian National Forest Inventory (SCANFI) using Landsat dense time series. Can. J. For. Res. 2024, 54, 793–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guindon, L.; Villemaire, P.; Correia, D.L.; Manka, F.; Sam, L.; Smiley, B. SCANFI: Spatialized CAnadian National Forest Inventory Data Product; Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, Laurentian Forestry Centre: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2023. [CrossRef]

- LaCarte, S. Canadian Forest Fire Danger Rating System (CFFDRS) Fire Behaviour Prediction (FBP) Fuel Types 2024, 30 M; Government of Canada, Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2024. Available online: https://open.canada.ca/data/dataset/4e66dd2f-5cd0-42fd-b82c-a430044b31de (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Latifovic, R. 2010 Land Cover of Canada; Government of Canada; Natural Resources Canada; Canada Centre for Remote Sensing. 2017. Available online: https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/c688b87f-e85f-4842-b0e1-a8f79ebf1133 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Latifovic, R. Canada’s Land Cover (ver. 2015); Natural Resources Canada, General Information Product, 119e, Natural Resources Canada. 2019. Available online: https://ostrnrcan-dostrncan.canada.ca/entities/publication/99dc3562-a6de-494a-9093-00f490f6df0a (accessed on 10 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Latifovic, R. Land Cover of Canada-Cartographic Product Collection; Government of Canada; Natural Resources Canada; Canada Centre for Remote Sensing. 2019. Available online: https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/11990a35-912e-4002-b197-d57dd88836d7 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Latifovic, R. 2015 Land Cover of Canada; Government of Canada; Natural Resources Canada; Canada Centre for Remote Sensing. 2023. Available online: https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/4e615eae-b90c-420b-adee-2ca35896caf6 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Latifovic, R. 2020 Land Cover of Canada; Government of Canada; Natural Resources Canada; Canada Centre for Remote Sensing. 2024. Available online: https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/ee1580ab-a23d-4f86-a09b-79763677eb47 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Environment and Climate Change Canada. Government of Canada Historical Climate Data; Canadian Centre for Climate Services: Gatineau, QC, Canada. Available online: https://dd.weather.gc.ca/today/climate/observations/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Shang, C.; Yang, F.; Huang, D.; Lyu, W. Data-driven soft sensor development based on deep learning technique. J. Process Control 2014, 24, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, E.; Strub, F.; De Vries, H.; Dumoulin, V.; Courville, A. Film: Visual reasoning with a general conditioning layer. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Gondal, M.W.; Wuthrich, M.; Miladinovic, D.; Locatello, F.; Breidt, M.; Volchkov, V.; Akpo, J.; Bachem, O.; Schölkopf, B.; Bauer, S. On the Transfer of Inductive Bias from Simulation to the Real World: A New Disentanglement Dataset. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Volume 32. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2019/file/d97d404b6119214e4a7018391195240a-Paper.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Dawson, H.L.; Dubrule, O.; John, C.M. Impact of dataset size and convolutional neural network architecture on transfer learning for carbonate rock classification. Comput. Geosci. 2023, 171, 105284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutakabbir, A.; Lung, C.H.; Zaman, M.; Naik, K.; Purcell, R.; Sampalli, S.; Ravichandran, T. Vegetation Land Cover and Forest Fires in Canada: An Analytical Data Visualization. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 49th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC), Toronto, ON, Canada, 8–11 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kondylatos, S.; Prapas, I.; Camps-Valls, G.; Papoutsis, I. Mesogeos: A Multi-Purpose Dataset for Data-Driven Wildfire Modeling in the Mediterranean. In Proceedings of the 37th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems Datasets and Benchmarks Track, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023; Available online: https://papers.nips.cc/paper_files/paper/2023/file/9ee3ed2dd656402f954ef9dc37e39f48-Paper-Datasets_and_Benchmarks.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Li, Y.; Li, K.; Li, G.; Wang, Z.; Ji, C.; Wang, L.; Zuo, D.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, F.; Wang, M.; et al. Sim2Real-Fire: A Multi-Modal Simulation Dataset for Forecast and Backtracking of Real-World Forest Fire. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–15 December 2024; Volume 37, pp. 1428–1442. Available online: https://papers.nips.cc/paper_files/paper/2024/file/02e978a2cc9a1d0d4376a7deb01db612-Paper-Datasets_and_Benchmarks_Track.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Abowarda, A.S.; Bai, L.; Zhang, C.; Long, D.; Li, X.; Huang, Q.; Sun, Z. Generating Surface Soil Moisture at 30m Spatial Resolution using Both Data Fusion and Machine Learning toward Better Water Resources Management at the Field Scale. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 255, 112301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Duan, S.B. Reconstruction of Daytime Land Surface Temperatures under Cloud-Covered Conditions using Integrated MODIS/Terra Land Products and MSG Geostationary Satellite Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 247, 111931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornebise, J.; Oršolić, I.; Kalaitzis, F. Open High-Resolution Satellite Imagery: The WorldStrat Dataset –With Application to Super-Resolution. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2022; Volume 35, pp. 25979–25991. Available online: https://papers.nips.cc/paper_files/paper/2022/file/a6fe99561d9eb9c90b322afe664587fd-Paper-Datasets_and_Benchmarks.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Giglio, L.; Justice, C. MOD14. NASA LP DAAC. 2015. Available online: https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/lpcloud-mod14-006 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Giglio, L.; Justice, C. MOD14A1. NASA LP DAAC. 2015. Available online: https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/lpcloud-mod14a1-006 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Giglio, L.; Justice, C. MOD14A2. NASA LP DAAC. 2015. Available online: https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/lpcloud-mod14a2-006 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Wang, D.; Zhang, J.; Du, B.; Xu, M.; Liu, L.; Tao, D.; Zhang, L. SAMRS: Scaling-up Remote Sensing Segmentation Dataset with Segment Anything Model. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023; Volume 36, pp. 8815–8827. Available online: https://papers.nips.cc/paper_files/paper/2023/file/1be3843e534ee06d3a70c7f62b983b31-Supplemental-Datasets_and_Benchmarks.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Yu, S.; Hannah, W.; Peng, L.; Lin, J.; Bhouri, M.A.; Gupta, R.; Lütjens, B.; Will, J.C.; Behrens, G.; Busecke, J.; et al. ClimSim: A Large Multi-Scale Dataset for Hybrid Physics-ML Climate Emulation. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023; Volume 36, pp. 22070–22084. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2023/file/45fbcc01349292f5e059a0b8b02c8c3f-Paper-Datasets_and_Benchmarks.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Zhou, H.; Kao, C.H.; Phoo, C.P.; Mall, U.; Hariharan, B.; Bala, K. AllClear: A Comprehensive Dataset and Benchmark for Cloud Removal in Satellite Imagery. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–15 December 2024; Volume 37, pp. 53571–53597. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2024/file/60095e1d7ebb292dbba93c4d8f7b2463-Paper-Datasets_and_Benchmarks_Track.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Akhtar, M.; Benjelloun, O.; Conforti, C.; Foschini, L.; Gijsbers, P.; Giner-Miguelez, J.; Goswami, S.; Jain, N.; Karamousadakis, M.; Krishna, S.; et al. Croissant: A Metadata Format for ML-Ready Datasets. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–15 December 2024; Volume 37, pp. 82133–82148. Available online: https://papers.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2024/file/9547b09b722f2948ff3ddb5d86002bc0-Paper-Datasets_and_Benchmarks_Track.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Khan, A.; Asad, M.; Benning, M.; Roney, C.; Slabaugh, G. Compositional Segmentation of Cardiac Images Leveraging Metadata. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Tucson, AZ, USA, 26 February–6 March 2025; pp. 9489–9498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meseguer-Brocal, G.; Peeters, G. Conditioned-U-Net: Introducing a Control Mechanism in the U-Net for Multiple Source Separations. In Proceedings of the 20th International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference, Delft, The Netherlands, 4–8 November 2019; Available online: https://archives.ismir.net/ismir2019/paper/000017.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-Image Translation with Conditional Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; Available online: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content_cvpr_2017/papers/Isola_Image-To-Image_Translation_With_CVPR_2017_paper.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Gao, Z.; Shi, X.; Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Yeung, D.Y. Earthformer: Exploring Space-Time Transformers for Earth System Forecasting. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2022; Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2022/file/a2affd71d15e8fedffe18d0219f4837a-Paper-Conference.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 4 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A.; Sheikh, H.; Simoncelli, E. Image quality assessment: From error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2004, 13, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Lyu, X.; Liu, F.; Gao, H.; Kaup, A. Frequency-Guided Denoising Network for Semantic Segmentation of Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2026, 64, 5400217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, F.; Yu, A.; Lyu, X.; Gao, H.; Zhou, J. A Frequency Decoupling Network for Semantic Segmentation of Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5607921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Coverage

Region | Coverage | Resolution | Images | Modality | Domain | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tile Area (km2) | Total Area (km2) | Temporal Period | Spatial | Temporal | |||||

| AllClear [60] | Worldwide | 6.5 | 155.5 K | 2022 | Fine (10 m) | NA | 4.3 M | Satellite | Cloud Removal |

| MODIS Thermal Anomaly [55,56,57] | Worldwide | 1.4 M | 149 M | 2000–2023 | Medium (1 km) | 5 min, 1 day, 8 days | 40 K | Satellite | Fire Segmentation |

| SolarCube [4] | Worldwide | 360 K | 6.84 M | 2018 | Coarse (5 km) | 15 min | 35 K | Derived Data Products, GBS | Solar Energy Forecasting |

| SAMRS [58] | Worldwide | 1–16.7 | ∼400 K | NA | NA | NA | 105 K | Satellite (Upsampled) | Segmentation |

| WorldStrat [54] | Worldwide | 2.5 | 10 K | 2017–2022 | Fine (1.5–60 m) | NA | 3449 | Satellite (Upsampled) | Super-Resolution |

| ClimSim [59] | Worldwide Simulated | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Satellite | Climate Simulation |

| ENS-10 [7] | Worldwide Simulated | NA | NA | 1998–2017 | Coarse (1 km) | 3.5 days | NA | Satellite | Weather Prediction |

| Sim2Real [51] | Worldwide Simulated | 130 | NA | 2013–2023 | Fine (30 m) | 1 h | 1 K (real), 1 M (simulated) | Topography, Vegetation, Satellite, Fuel, and GBS | Wildfire Spread |

| Mesogeos [50] | Mediterranean | 4096 | 9 M | 2006–2022 | Coarse (1 km) | 1 day | 25 K | Vegetation, Climate, and Anthropogenic | Wildfire Spread |

| NOAH (Our) | Canada (Expandable to Worldwide) | 40,000 | 8,742,469 | 2013–2025 | Fine (30 m) | 1 h | 234,089 | Topography, Vegetation, Satellite, Fuel, and GBS | Soft Sensors, Super-Resolution, Cloud Removal, GM, etc. |

| Generated Landsat 8 Band | UNet + FiLM | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| MSE | SSIM | PSNR | |

| Band 1 (B1): Ultra Blue, Coastal Aerosol | |||

| Band 2 (B2): Blue | |||

| Band 3 (B3): Green | |||

| Band 4 (B4): Red | |||

| Band 5 (B5): Near InfraRed | |||

| Band 6 (B6): Shortwave InfraRed (1.57–1.65 µm) | |||

| Band 7 (B7): Shortwave InfraRed (2.11–2.29 µm) | |||

| Band 8 (B8): Panchromatic | |||

| Band 9 (B9): Cirrus | |||

| Band 10 (B10)-TIR (10.60–11.19 µm) | |||

| Band 11 (B11)-TIR (11.50–12.51 µm) | |||

| Bands | w/o Biomass | w/o Crown Cover | w/o Fuel Types | w/o Land Cover | w/o Topography | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSE | SSIM | PSNR | MSE | SSIM | PSNR | MSE | SSIM | PSNR | MSE | SSIM | PSNR | MSE | SSIM | PSNR | |

| B1 | 1.25 | 0.18 | −2.80 | 0.68 | 0.22 | −1.77 | 1.25 | 0.03 | −6.92 | 0.97 | 0.09 | −5.19 | 0.77 | 0.08 | −1.91 |

| B2 | 0.85 | 0.25 | −1.05 | 0.94 | 0.09 | −3.82 | 1.13 | 0.10 | −0.25 | 1.09 | 0.21 | −1.75 | 1.05 | 0.14 | 2.08 |

| B3 | 1.18 | 0.14 | 1.60 | 0.88 | 0.13 | −3.21 | 1.17 | 0.11 | −2.22 | 1.18 | 0.12 | −0.94 | 0.76 | 0.12 | −4.56 |

| B4 | 0.85 | 0.17 | −1.76 | 1.17 | 0.01 | −4.83 | 0.98 | 0.20 | −0.55 | 1.70 | 0.20 | −0.29 | 0.76 | 0.17 | −1.45 |

| B5 | 1.65 | 0.00 | −6.47 | 1.42 | 0.04 | −3.90 | 3.05 | 0.03 | −3.04 | 2.13 | 0.08 | −2.65 | 1.30 | 0.06 | −3.60 |

| B6 | 4.14 | 0.04 | −3.96 | 2.59 | 0.01 | −5.49 | 1.13 | 0.11 | −2.18 | 1.49 | 0.07 | −5.95 | 3.76 | 0.03 | −3.49 |

| B7 | 1.86 | 0.01 | −5.95 | 1.91 | 0.00 | −7.75 | 1.76 | 0.00 | −10.37 | 1.22 | 0.00 | −6.28 | 1.11 | 0.00 | −2.57 |

| B8 | 1.70 | 0.10 | −0.30 | 0.99 | 0.10 | −0.86 | 1.10 | 0.14 | −1.75 | 1.28 | 0.07 | −0.98 | 1.19 | 0.06 | −1.43 |

| B9 | 1.71 | 0.19 | −0.96 | 0.93 | 0.39 | −0.53 | 1.02 | 0.37 | 0.44 | 1.12 | 0.49 | −2.02 | 0.78 | 0.57 | 0.64 |

| B10 | 0.87 | 0.34 | −1.01 | 0.76 | 0.44 | 1.13 | 0.69 | 0.45 | 2.48 | 0.72 | 0.34 | −1.58 | 1.56 | 0.11 | −5.01 |

| B11 | 0.68 | 0.42 | 3.11 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.21 | 0.96 | 0.41 | 3.27 | 0.67 | 0.37 | 2.17 | 0.62 | 0.55 | 1.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mutakabbir, A.; Lung, C.-H.; Zaman, M.; Upadhyay, D.; Naik, K.; Millard, K.; Ravichandran, T.; Purcell, R. NOAH: A Multi-Modal and Sensor Fusion Dataset for Generative Modeling in Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030466

Mutakabbir A, Lung C-H, Zaman M, Upadhyay D, Naik K, Millard K, Ravichandran T, Purcell R. NOAH: A Multi-Modal and Sensor Fusion Dataset for Generative Modeling in Remote Sensing. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(3):466. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030466

Chicago/Turabian StyleMutakabbir, Abdul, Chung-Horng Lung, Marzia Zaman, Darshana Upadhyay, Kshirasagar Naik, Koreen Millard, Thambirajah Ravichandran, and Richard Purcell. 2026. "NOAH: A Multi-Modal and Sensor Fusion Dataset for Generative Modeling in Remote Sensing" Remote Sensing 18, no. 3: 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030466

APA StyleMutakabbir, A., Lung, C.-H., Zaman, M., Upadhyay, D., Naik, K., Millard, K., Ravichandran, T., & Purcell, R. (2026). NOAH: A Multi-Modal and Sensor Fusion Dataset for Generative Modeling in Remote Sensing. Remote Sensing, 18(3), 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030466