Beyond In Situ Measurements: Systematic Review of Satellite-Based Approaches for Monitoring Dissolved Oxygen Concentrations in Global Surface Waters

Highlights

- Satellite remote sensing can effectively estimate surface dissolved oxygen using empirical, semi-empirical, machine learning, and deep learning approaches.

- Machine learning and deep learning models significantly improve DO prediction when supported by high-quality in situ data.

- Remote sensing DO estimation enables large-scale, cost-effective monitoring of hypoxia, eutrophication, and deoxygenation.

- Reliable application requires rigorous validation and continuous recalibration with field observations.

Abstract

1. Introduction

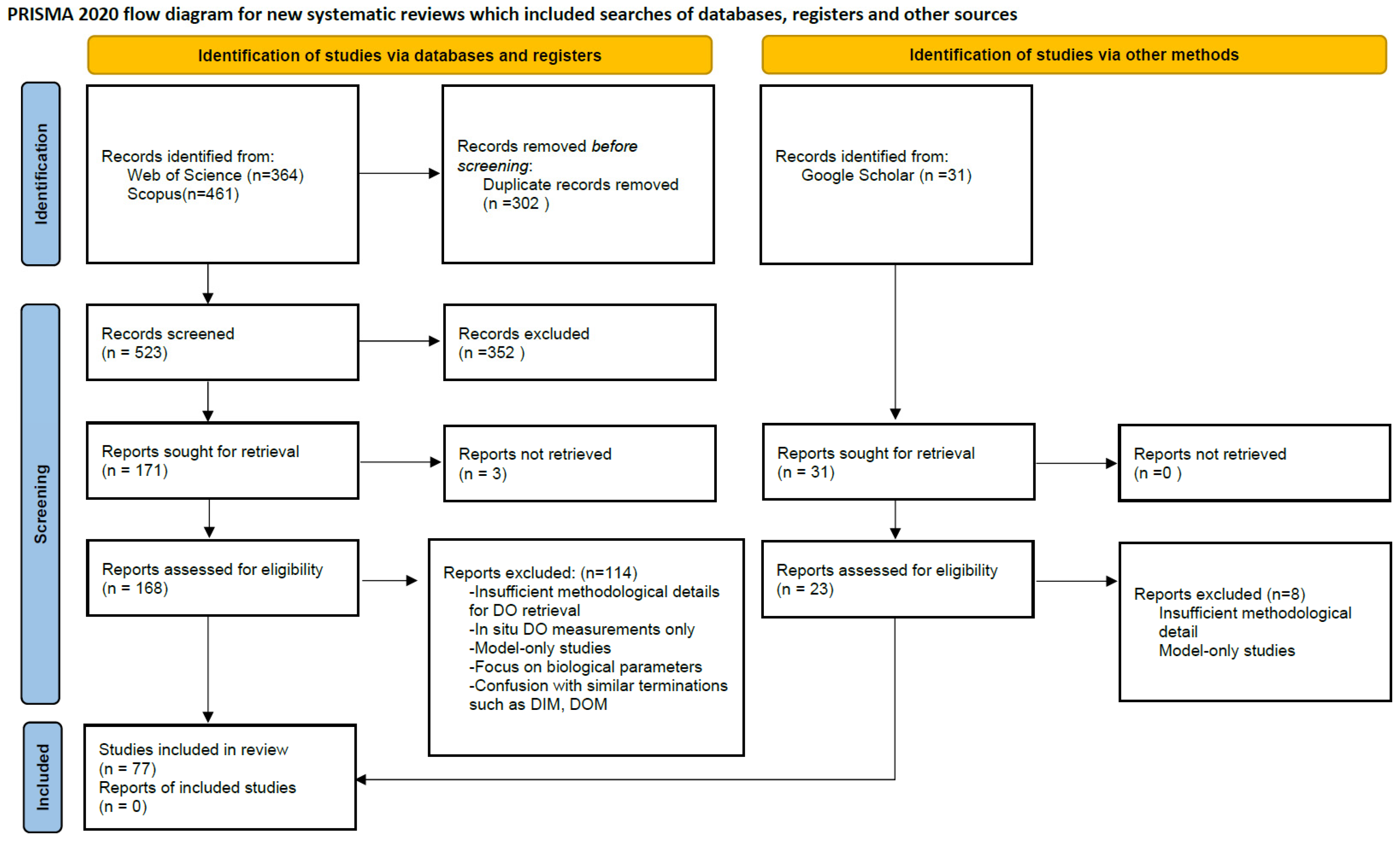

2. Materials and Methods

3. State of the Art

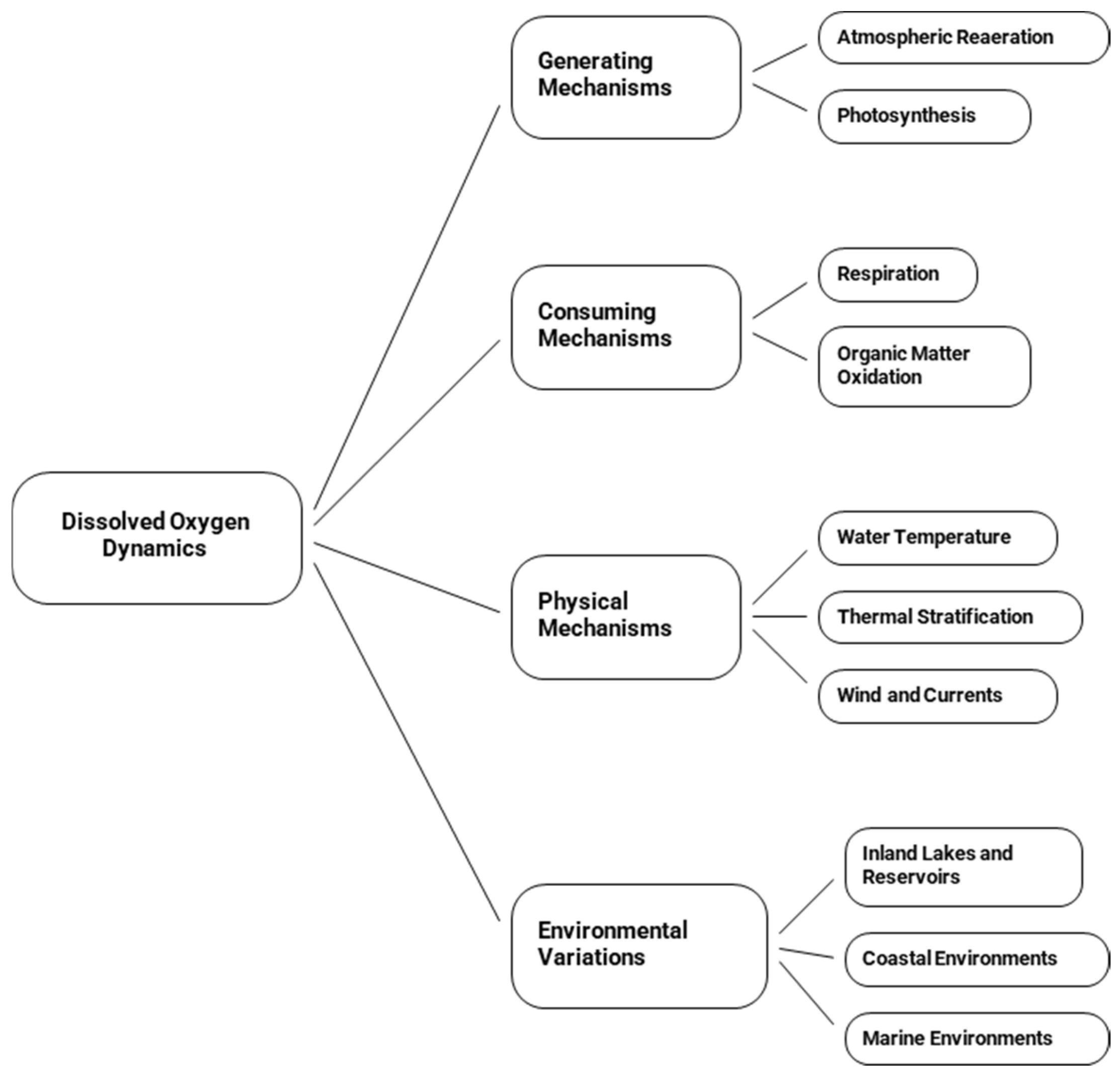

3.1. Key Drivers and Dynamics of the Dissolved Oxygen Variability in the Aquatic Environment

3.2. Remote Sensing of Optical and Thermal Properties Relevant to DO Retrieval

| Sensor | Spatial Resolution (m) | Temporal Resolution | Key Bands/ Features | DO Retrieval Role | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landsat-8/9 OLI/TIRS | 15–100 | 16 days | Multispectral + thermal | SST, proxies for DO | [1,25,35,36,46,47,48,49] |

| Sentinel-2 MSI | 10–60 | 5 days | High resolution visible (B,G,R)/NIR | Chl-a, TSM proxies | [36,37,38,45,50] |

| MODIS (Terra/Aqua) | 250–1000 | 1–2 days | Multispectral + thermal | SST, proxy mapping | [1,17,51,52] |

| Himawari-8 (H8) | Geo-stationary | 10 min | Visible/infrared | - | [3] |

| GOCI | 500 | hourly | - | detecting hypoxia event | [53] |

| ZY1-02D Hyperspectral | 30 | 5 days | Hyperspectral | Proxy detection | [37] |

3.3. Field Measurements

4. Algorithmic Approaches for Satellite-Based Dissolved Oxygen Retrieval

4.1. Empirical Models

4.1.1. Definition of Empirical Models and Case Studies

4.1.2. Advantages of Empirical Studies

4.1.3. Limitations of Empirical Models

4.2. Semi-Empirical Methods

4.2.1. Definition of Semi-Empirical and Case Studies

4.2.2. Advantages of Semi-Empirical Studies

4.2.3. Limitations of Semi-Empirical Studies

4.3. Multivariable Machine Learning (ML) Models

4.3.1. Definition of Multivariable Machine Learning (ML) Models and Case Studies

4.3.2. Advantages of Machine Learning Approaches

4.3.3. Limitations of Machine Learning Approaches

4.4. Deep Learning Models

4.4.1. Definition of Deep Learning (DL) Models and Case Studies

4.4.2. Advantages of Deep Learning Approaches

4.4.3. Limitations of Deep Learning Models

5. Discussions

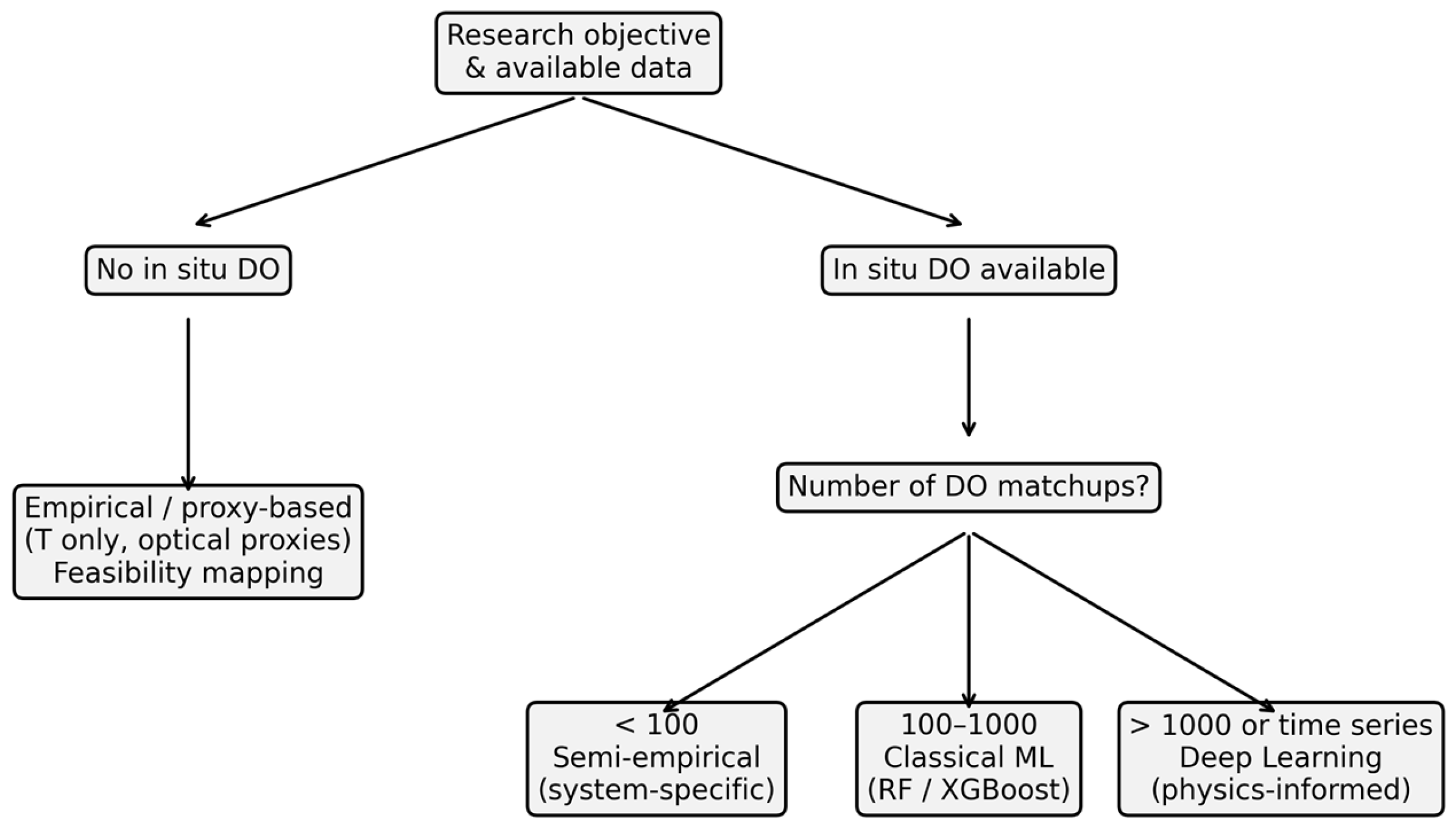

5.1. Proposed Protocol for Methodology Selection to Generate Satellite-Derived DO Concentrations

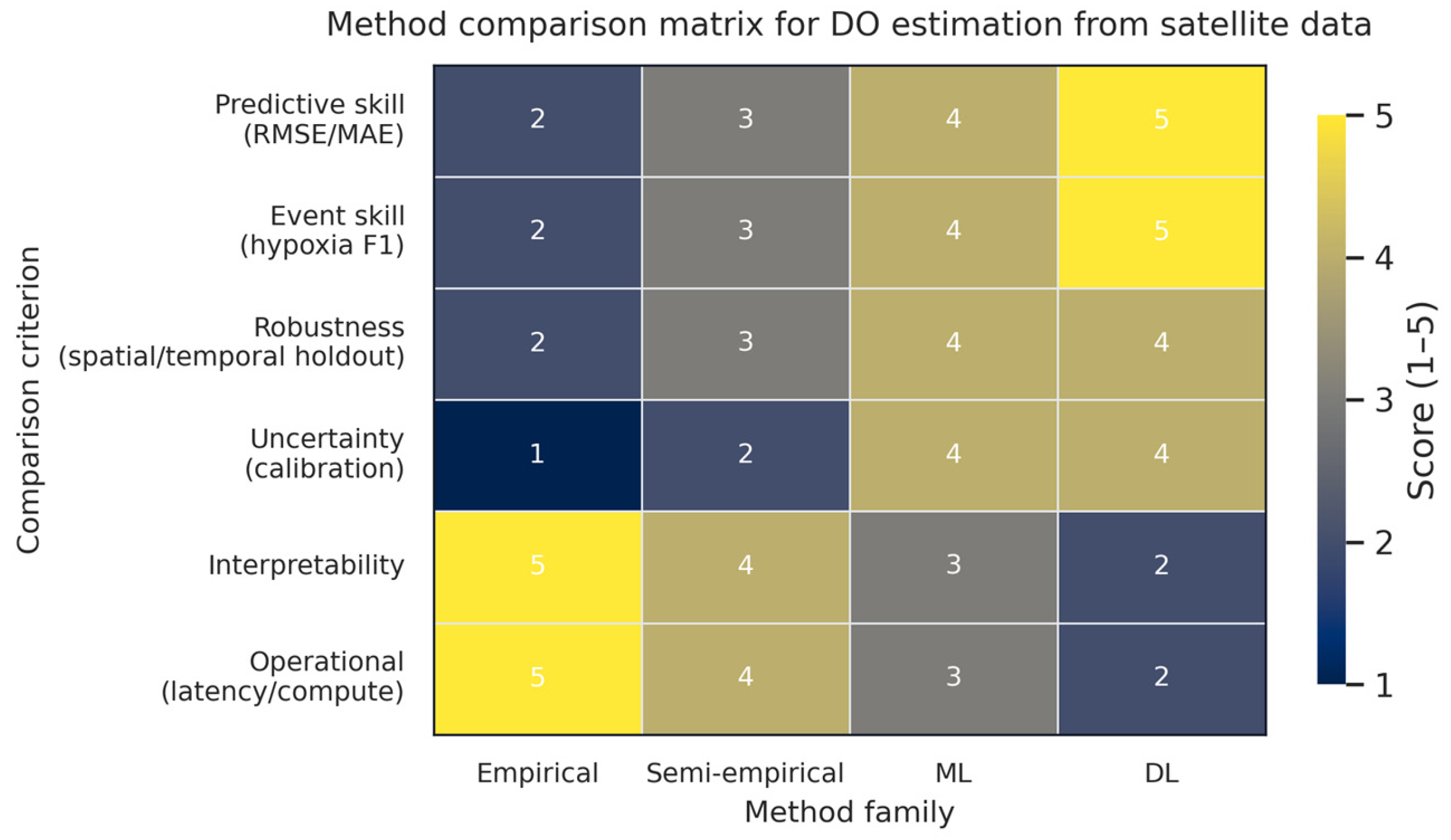

5.2. Comparative Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BOD | Biochemical Oxygen Demand |

| CBP | Chesapeake Bay Program |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| CDOM | Colored Dissolved Organic Material |

| Chl-a | Chlorophyll-a |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DO | Dissolved Oxygen. |

| DO-MDNN | Dissolved Oxygen Multimodal Deep Neural Network |

| DO-T | Dissolved Oxygen-Temperature |

| FDOM | Fluorescent Dissolved Organic Matter |

| GLODAPv2 | Global Ocean Data Analysis Project |

| KOEM | Korea Marine Environment Management Corporation |

| LMG | Lindeman–Merenda–Gold |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MLR | Multiple Linear Regression |

| ML/DL | Machine Learning/Deep Learning |

| NOAP | Non-Optically Active Parameter |

| OACs | Optically Active Constituents |

| OMZs | Oxygen Minimum Zones |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| RS | Remote Sensing |

| RSR | Response Surface Regression |

| SMAPE | Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| SST | Sea Surface Temperature |

| SPM | Suspended Particulate Matter |

| TIR | Thermal Infrared |

| TN | Total Nitrogen |

| TP | Total Phosphorus |

| TSS | Total Suspended Solids |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| WOD | World Ocean Database |

| XAI | Explainable AI |

| 2D-CNN | Two-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network |

References

- Guo, H.; Huang, J.J.; Zhu, X.; Wang, B.; Tian, S.; Xu, W.; Mai, Y. A Generalized Machine Learning Approach for Dissolved Oxygen Estimation at Multiple Spatiotemporal Scales Using Remote Sensing. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 288, 117734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.; Zhou, G.; Jing, G.; PabloAntezana Lopez, F.; Sun, K.; Jiang, C.; Ma, Z.; Tan, Y. XGB-2D CNN-Based Dissolved Oxygen Inversion for Coastal Water. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 21289–21304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Lang, Q.; Wang, P.; Yang, W.; Chen, G.; Yin, H.; Zhang, Q.; Li, W.; Wang, H. Dissolved Oxygen Concentration Inversion Based on Himawari-8 Data and Deep Learning: A Case Study of Lake Taihu. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1230778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutsen, Ø.; Stefanakos, C.; Slagstad, D.; Ellingsen, I.; Zacharias, I.; Biliani, I.; Berg, A. Studying the Evolution of Hypoxia/Anoxia in Aitoliko Lagoon, Greece, Based on Measured and Modeled Data. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1299202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigaud, S.; Deflandre, B.; Grenz, C.; Cesbron, F.; Pozzato, L.; Voltz, B.; Grémare, A.; Romero-Ramirez, A.; Mirleau, P.; Meulé, S.; et al. Benthic Oxygen Dynamics and Implication for the Maintenance of Chronic Hypoxia and Ecosystem Degradation in the Berre Lagoon (France). Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2021, 258, 107437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forth, M.; Liljebladh, B.; Stigebrandt, A.; Hall, P.O.J.; Treusch, A.H. Effects of Ecological Engineered Oxygenation on the Bacterial Community Structure in an Anoxic Fjord in Western Sweden. ISME J. 2015, 9, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, I.; Hossain, S.A.; Roy, S.K.; Karmakar, J.; Jose, F.; De, T.K.; Nguyen, T.T.; Elkhrachy, I.; Nguyen, N.M. Assessing Intra and Interannual Variability of Water Quality in the Sundarban Mangrove Dominated Estuarine Ecosystem Using Remote Sensing and Hybrid Machine Learning Models. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 442, 140889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, A.H.; Diaz, R.J. Dead Zones: Oxygen Depletion in Coastal Ecosystems, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; ISBN 9780128050521. [Google Scholar]

- Ping, B.; Meng, Y.; Su, F.; Xue, C.; Li, Z.; Yuan, Z. Distribution of Surface Dissolved Oxygen Fronts in China’s Marginal Seas. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2025, 130, e2025JC022789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xue, C.; Ping, B. A Reconstructing Model Based on Time–Space–Depth Partitioning for Global Ocean Dissolved Oxygen Concentration. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triana, K.; Wahyudi, A.J. Dissolved Oxygen Variability of Indonesian Seas over Decades as Detected by Satellite Remote Sensing. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 925, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, K.T.; Sagan, V.; Sloan, J.J. Deep Learning-Based Water Quality Estimation and Anomaly Detection Using Landsat-8/Sentinel-2 Virtual Constellation and Cloud Computing. GISci. Remote Sens. 2020, 57, 510–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, T.; Kim, K. High-Resolution Spatio-Temporal Monitoring of Coastal Hypoxia Using Machine Learning Models and GOCI–MODIS Satellite Data. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2026, 222, 118871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Shao, J.; Chen, Y.; Qi, J.; Wu, S.; Zhang, F.; He, X.; Du, Z. Reconstruction of Dissolved Oxygen in the Indian Ocean from 1980 to 2019 Based on Machine Learning Techniques. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1291232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gani, M.A.; Sajib, A.M.; Siddik, M.A.; Moniruzzaman, M. Assessing the Impact of Land Use and Land Cover on River Water Quality Using Water Quality Index and Remote Sensing Techniques. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Nalgire, S.M.; Gupta, M.; Chinnasamy, P. Potential of Open Source Remote Sensing Data for Improved Spatiotemporal Monitoring of Inland Water Quality in India: Case Study of Gujarat. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2022, 88, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, L.; Qiu, F. Using MODIS Data to Track the Long-Term Variations of Dissolved Oxygen in Lake Taihu. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1096843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, E.A.L.; Kumaran, S.S.; Partee, E.B.; Willis, L.P.; Mitchell, K. Potential of Mapping Dissolved Oxygen in the Little Miami River Using Sentinel-2 Images and Machine Learning Algorithms. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2022, 26, 100759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, C.; Zhang, Z. Multispectral Remote Sensing for Estimating Water Quality Parameters: A Comparative Study of Inversion Methods Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). Sustainability 2023, 15, 10298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Yu, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, N.; Ali, S. Reconstruction of the Three-Dimensional Dissolved Oxygen and Its Spatio-Temporal Variations in the Mediterranean Sea Using Machine Learning. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 157, 710–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; He, Y. Assessing Dissolved Oxygen Dynamics in the North Mainstream of the Dongjiang River, China Using Remote Sensing and Field Measurements. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Kong, J.; Hu, H.; Du, Y.; Gao, M.; Chen, F. A Review of Remote Sensing for Water Quality Retrieval: Progress and Challenges. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wen, X.; Luo, D.; Tan, Y. Study on Water Quality Inversion Model of Dianchi Lake Based on Landsat 8 Data. J. Spectrosc. 2022, 2022, 3341713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajib, A.M.; Uddin, M.G.; Rahman, A.; Ahmadian, R.; Olbert, A.I. Remote Sensing Applications for Monitoring Optically Inactive Water Quality Indicators: A Comprehensive Review. Earth Sci. Rev. 2025, 271, 105259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Wang, D.; Song, L.; Gong, F.; Chen, S.; Huang, J.; He, X. Monitoring Dissolved Oxygen Concentrations in the Coastal Waters of Zhejiang Using Landsat-8/9 Imagery. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Sun, B.; Xue, C.; Zheng, Z.; Ma, Y. An Enhanced Transfer Learning Remote Sensing Inversion of Coastal Water Quality: A Case Study of Dissolved Oxygen. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 21065–21076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Huang, S.; Chen, Y.; Qi, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Liu, R.; Du, Z. Satellite-Based Global Sea Surface Oxygen Mapping and Interpretation with Spatiotemporal Machine Learning. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Pierson, D.C.; Ladwig, R.; Kraemer, B.M.; Hu, F.R.S. Multi-Model Machine Learning Approach Accurately Predicts Lake Dissolved Oxygen with Multiple Environmental Inputs. Earth Space Sci. 2024, 11, e2023EA003473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxa, M.; Musil, M.; Kummel, M.; Hanzlík, P.; Tesařová, B.; Pechar, L. Dissolved Oxygen Deficits in a Shallow Eutrophic Aquatic Ecosystem (Fishpond)—Sediment Oxygen Demand and Water Column Respiration Alternately Drive the Oxygen Regime. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 766, 142647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toming, K.; Liu, H.; Soomets, T.; Uuemaa, E.; Nõges, T.; Kutser, T. Estimation of the Biogeochemical and Physical Properties of Lakes Based on Remote Sensing and Artificial Intelligence Applications. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.N.; Moore, W.S.; Chappel, S.L.; Viso, R.F.; Libes, S.M.; Peterson, L.E. A New Perspective on Coastal Hypoxia: The Role of Saline Groundwater. Mar. Chem. 2016, 179, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, N.; Fakiris, E.; Koutsikopoulos, C.; Papatheodorou, G.; Christodoulou, D.; Dimas, X.; Geraga, M.; Kapellonis, Z.G.; Vaziourakis, K.M.; Noti, A.; et al. Spatio-Seasonal Hypoxia/Anoxia Dynamics and Sill Circulation Patterns Linked to Natural Ventilation Drivers, in a Mediterranean Landlocked Embayment: Amvrakikos Gulf, Greece. Geosciences 2021, 11, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjovu, G.E.; Stephen, H.; James, D.; Ahmad, S. Overview of the Application of Remote Sensing in Effective Monitoring of Water Quality Parameters. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, S.; Liu, C.; Qian, B.; Miao, Q. Remote Sensing-Based Water Quality Assessment for Urban Rivers: A Study in Linyi Development Area. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 34586–34595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, M.H.; Melesse, A.M.; Reddi, L. A Comprehensive Review on Water Quality Parameters Estimation Using Remote Sensing Techniques. Sensors 2016, 16, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.; Mumtaz, R.; Anwar, Z.; Shaukat, A.; Arif, O.; Shafait, F. A Multi–Step Approach for Optically Active and Inactive Water Quality Parameter Estimation Using Deep Learning and Remote Sensing. Water 2022, 14, 2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Gong, C.; Ji, T.; Hu, Y.; Li, L. Water Quality Retrieval from ZY1-02D Hyperspectral Imagery in Urban Water Bodies and Comparison with Sentinel-2. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Guo, H.; Xu, W.; Zhu, X.; Wang, B.; Zeng, Q.; Mai, Y.; Huang, J.J. Remote Sensing Retrieval of Inland Water Quality Parameters Using Sentinel-2 and Multiple Machine Learning Algorithms. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 18617–18630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.; Wang, D.; Cai, S.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Q.; Li, Z.; Yang, X.; Picco, L. Retrieval of Dissolved Oxygen Concentrations in Fishponds in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area Using Satellite Imagery and Machine Learning. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, S.; Cui, T.; Lai, Q.; Bao, Y.; Diao, R.; Yue, Y.; Hao, Y. Improving Remote Sensing Retrieval of Water Clarity in Complex Coastal and Inland Waters with Modified Absorption Estimation and Optical Water Classification Using Sentinel-2 MSI. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 102, 102377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shi, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, G.; Qin, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhu, M.; Dong, B.; Guo, Y. Remote Sensing of Column-Integrated Chlorophyll a in a Large Deep-Water Reservoir. J. Hydrol. 2022, 610, 127918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, P.; Saha, K.; Digiacomo, P.; Miller, S.D.; Zhang, H.M.; Lazzaro, R.; Son, S. Trends in Satellite-Based Ocean Parameters through Integrated Time Series Decomposition and Spectral Analysis. Part I: Chlorophyll, Sea Surface Temperature, and Sea Level Anomaly. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2025, 42, 91–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafzadeh, M.; Basirian, S. Evaluation of River Water Quality Index Using Remote Sensing and Artificial Intelligence Models. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhu, X.; Jeanne Huang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, S.; Chen, Y. An Enhanced Deep Learning Approach to Assessing Inland Lake Water Quality and Its Response to Climate and Anthropogenic Factors. J. Hydrol. 2023, 620, 129466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualhin, K.; Abushaban, S. Predictive Models of Non-Optically Active Coastal Water Quality Parameters by Remote Sensing Imagery. Marit. Technol. Res. 2025, 7, 274944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Gong, C.; Huai, H.; Wu, E.; Lu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Li, L.; Yang, Z. Retrieval of Water Quality Parameters in Dianshan Lake Based on Sentinel-2 MSI Imagery and Machine Learning: Algorithm Evaluation and Spatiotemporal Change Research. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shaibah, B.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Tong, Z.; Zhang, M.; El-Zeiny, A.; Faichia, C.; Hussain, M.; Tayyab, M. Modeling Water Quality Parameters Using Landsat Multispectral Images: A Case Study of Erlong Lake, Northeast China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.B.; Yurembam, G.S.; Jhajharia, D.; Kusre, B.C. Water Quality Assessment of Loktak Lake, Manipur Using Landsat 9 Imagery. Water Pract. Technol. 2024, 19, 2613–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Mohammed, S.; El-Shazly, A.; Morsy, S. Tigris River Water Surface Quality Monitoring Using Remote Sensing Data and GIS Techniques. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2023, 26, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, L. A Feature Selection Method Based on Relief Feature Ranking with Recursive Feature Elimination for the Inversion of Urban River Water Quality Parameters Using Multispectral Imagery from an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Water 2024, 16, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashtan Sundararaman, H.K.; Shanmugam, P. Estimates of the Global Ocean Surface Dissolved Oxygen and Macronutrients from Satellite Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 311, 114243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Son, S.; Kim, H.C.; Kim, B.; Park, Y.G.; Nam, J.; Ryu, J. Application of Satellite Remote Sensing in Monitoring Dissolved Oxygen Variabilities: A Case Study for Coastal Waters in Korea. Environ. Int. 2020, 134, 105301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Huang, C.; Meng, L.; Lu, L.; Wu, Y.; Fan, R.; Li, S.; Sui, Z.; Huang, T.; Huang, C.; et al. Eutrophication and Lakes Dynamic Conditions Control the Endogenous and Terrestrial {POC} Observed by Remote Sensing: Modeling and Application. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 107907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martellucci, R.; Menna, M.; Mauri, E.; Pirro, A.; Gerin, R.; Paladini de Mendoza, F.; Garić, R.; Batistić, M.; di Biagio, V.; Giordano, P.; et al. Recent Changes of the Dissolved Oxygen Distribution in the Deep Convection Cell of the Southern Adriatic Sea. J. Mar. Syst. 2024, 245, 103988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Schollaert Uz, S.; St-Laurent, P.; Friedrichs, M.A.M.; Mehta, A.; DiGiacomo, P.M. Hypoxia Forecasting for Chesapeake Bay Using Artificial Intelligence. Artif. Intell. Earth Syst. 2024, 3, 230054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Huang, S.; Wang, X. Monitoring Water Quality Parameters of Taihu Lake Based on Remote Sensing Images and LsTM-RnN. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 188068–188081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, M.R.W.; Özdoğan, M.; Block, P.J. A Machine Learning and Remote Sensing-Based Model for Algae Pigment and Dissolved Oxygen Retrieval on a Small Inland Lake. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR035744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, A. Remote Sensing-Based Water Quality Parameters Retrieval Methods: A Review. East Afr. J. Environ. Nat. Resour. 2024, 7, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizani, F.M.C.; Maillard, P.; Ferreira, A.F.F.; De Amorim, C.C. Estimation of Water Quality in a Reservoir from Sentinel-2 Msi and Landsat-8 Oli Sensors. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, 5, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ouali, A.; El Hafyani, M.; Roubil, A.; Lahrach, A.; Essahlaoui, A.; Hamid, F.E.; Muzirafuti, A.; Paraforos, D.S.; Lanza, S.; Randazzo, G. Modeling and Spatiotemporal Mapping of Water Quality through Remote Sensing Techniques: A Case Study of the Hassan Addakhil Dam. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibisana, H.; Aryaseta, B.; Wardhani, P.C. Analysis of Dissolved Oxygen on Tuban Coast Using Remote Sensing Algorithms From Landsat 8 Satellite Image Data and Interpolated Polynomials. Rev. Gest. Soc. Ambient. 2024, 18, e05321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Martínez, J.L.; Perera-Burgos, J.A.; Acosta-González, G.; Alvarado-Flores, J.; Li, Y.; Leal-Bautista, R.M. Assessment of Physicochemical Parameters by Remote Sensing of Bacalar Lagoon, Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico. Water 2024, 16, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Zhang, J.; Meng, H.; Lai, Y.; Xu, M. Remote Sensing Inversion of Water Quality Parameters in the Yellow River Delta. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 155, 110914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Wang, P.; Yin, H.; Lang, Q.; Wang, H.; Chen, G. Dissolved Oxygen Concentration Inversion Based on Himawari-8 Imagery and Machine Learning: A Case Study of Lake Chaohu. Water 2023, 15, 3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theologou, I.; Patelaki, M.; Karantzalos, K. Can Single Empirical Algorithms Accurately Predict Inland Shallow Water Quality Status from High Resolution, Multi-Sensor, Multi-Temporal Satellite Data? Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2015, 40, 1511–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Montes, E.E.; Durango-Banquett, M.M.; Torres-Bejarano, F.M.; Campo-Daza, G.A.; Padilla-Mendoza, C. Remote Sensing Application Using Landsat 8 Images for Water Quality Assessments. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2475, 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, L.; Liu, S.; Shi, Z.; Shi, C. The Application of Remote Sensing Technology in Inland Water Quality Monitoring and Water Environment Science: Recent Progress and Perspectives. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batur, E.; Maktav, D. Assessment of Surface Water Quality by Using Satellite Images Fusion Based on PCA Method in the Lake Gala, Turkey. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 2983–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arief, M. Development of Dissolved Oxygen Concentration Extraction Model Using Landsat Data Case Study: Ringgung Coastal Waters. Int. J. Remote Sens. Earth Sci. 2017, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abayazid, H.O.; El-Adawy, A. Assessment of a Non-Optical Water Quality Property Using Space-Based Imagery in Egyptian Coastal Lake. J. Water Resour. Prot. 2019, 11, 713–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Fan, Z.; Zhao, M. A New Approach for Estimating Dissolved Oxygen Based on a High-accuracy Surface Modeling Method. Sensors 2021, 21, 3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Loiselle, S.A.; Yang, D.; Ma, R.; Su, W.; Gao, C. Remote Estimation of Chlorophyll a Concentrations over a Wide Range of Optical Conditions Based on Water Classification from VIIRS Observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 241, 111735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethy, D.K. Predicting Water Quality Using Ensemble Machine Learning Models and Remote Sensing Data. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 11, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, L.A.; Breitburg, D.L. Linking Coasts and Seas to Address Ocean Deoxygenation. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 401–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quang, N.H.; Dinh, N.T.; Dien, N.T.; Son, L.T. Calibration of Sentinel-2 Surface Reflectance for Water Quality Modelling in Binh Dinh’s Coastal Zone of Vietnam. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Guo, H.; Huang, J.J.; Tian, S.; Xu, W.; Mai, Y. An Ensemble Machine Learning Model for Water Quality Estimation in Coastal Area Based on Remote Sensing Imagery. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 323, 116187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Fu, B.; Li, S.; Lao, Z.; Deng, T.; He, W.; He, H.; Chen, Z. Monitoring Multi-Water Quality of Internationally Important Karst Wetland through Deep Learning, Multi-Sensor and Multi-Platform Remote Sensing Images: A Case Study of Guilin, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Modeling Approach | Satellite Sensors | Spatial Resolution | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical or statistical | Ocean-color/TIR, Landsat (OLI, TM, ETM+), Sentinel-2 (MSI), MODIS (Aqua/Terra/VIIRS), and Himawari-8 | 10–60 m (S2 MSI), 30 m (Landsat), 250 m–1 km (typical ocean color) | [16,25,59] |

| Deep learning | Sentinel-2, Landsat (TM/ETM+/OLI) MODIS (ocean color/TIR), Himawari-8 | 10–60 m (S2 MSI), 15–30 m, 250 m–1 km (MODIS) | [3,12,14,44] |

| Machine learning | Sentinel-2 (optical); RS used together with in situ time series, Landsat (TM/ETM+/OLI), MODIS, Himawari-8 | 10–60 m (S2 MSI), 250 m–1 km (MODIS), 15–30 m | [18,27] |

| Semi-empirical or physics-constrained/spatial-statistical | Satellite-derived reflectance + numerical model/forcing | 30 m (Landsat), 10–60 m (S2 MSI), 250 m–1 km (MODIS) | [9,17,21] |

| Main purpose |

|

| Suitable application |

|

| Data requirements |

|

| Limitations |

|

| Main purpose |

|

| Suitable application |

|

| Data requirements |

|

| Limitations |

|

| Main purpose |

|

| Suitable application |

|

| Data requirements |

|

| Limitations |

|

| Main purpose |

|

| Suitable application |

|

| Data requirements |

|

| Limitations |

|

| DO Retrieval Methodology Classification | Water Body Type | n Studies | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical or statistical | Coastal Waters | 3 | [25,45,59] |

| Lakes | 2 | [16,70] | |

| Deep learning | Lakes | 3 | [3,12,44] |

| Sea | 1 | [20] | |

| River | 1 | [12] | |

| Machine learning | River | 1 | [18] |

| Ocean | 1 | [27] | |

| Semi-empirical or physics-constrained | River | 1 | [21] |

| Lake | 1 | [17] | |

| Ocean | 1 | [51] | |

| Sea | 1 | [9] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Biliani, I.; Zacharias, I. Beyond In Situ Measurements: Systematic Review of Satellite-Based Approaches for Monitoring Dissolved Oxygen Concentrations in Global Surface Waters. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 428. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030428

Biliani I, Zacharias I. Beyond In Situ Measurements: Systematic Review of Satellite-Based Approaches for Monitoring Dissolved Oxygen Concentrations in Global Surface Waters. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(3):428. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030428

Chicago/Turabian StyleBiliani, Irene, and Ierotheos Zacharias. 2026. "Beyond In Situ Measurements: Systematic Review of Satellite-Based Approaches for Monitoring Dissolved Oxygen Concentrations in Global Surface Waters" Remote Sensing 18, no. 3: 428. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030428

APA StyleBiliani, I., & Zacharias, I. (2026). Beyond In Situ Measurements: Systematic Review of Satellite-Based Approaches for Monitoring Dissolved Oxygen Concentrations in Global Surface Waters. Remote Sensing, 18(3), 428. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030428