Highlights

What are the main findings?

- NFV scheme: FY4A AMVs nudge 12 km flow, then force 1 km 3DVar, sharply improves Zhengzhou 7.20 rainstorm pattern.

- NFV beats 3DVar/nudging: 6 h rain MODE interest 0.96, halves centroid distance, tops > 45 dBZ fraction, lowest false alarms.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Scale-dependent AMVs assimilation (nudge → Var) are ready for rapid-update nowcasting of localized convective extremes.

- NFV blueprint is transferable to Himawari/GOES, boosting cloudy-region heavy-rain prediction and disaster-risk reduction.

Abstract

Geostationary atmospheric motion vectors (e.g., FY4A AMVs) are routine mid-upper atmospheric observations used in numerical weather prediction (NWP) models, yet their complex spatiotemporal errors and assimilation limitations, i.e., high-temporal/coarse-spatial data and large-scale-adjustment/direct-assimilation scheme, leave unclear impacts of AMVs assimilation on nowcasting forecasts. To this end, a Nudging-Forced–3DVar scheme (NFV) is designed within a multi-scale (i.e., 12, 4, and 1 km) regional NWP framework to exploit AMVs characteristics; ablation experiments for the Zhengzhou “7.20” rainstorm isolate Nudging and 3DVar impacts on assimilation and nowcasting. Results show the following: (1) large-scale Nudging and high-resolution 3DVar both improve mid-upper analyses, with the former ingesting more observations; (2) Nudging retains large-scale background updates but yields significant misses, whereas 3DVar intensifies rainfall extremes yet blurs fine structures; (3) NFV merges its strengths, modulating deep convection through upper-level systems and markedly improving rainfall spatiotemporal patterns. Therefore, NFV is recommended for the FY4A AMVs’ future numerical nowcasting, which provides useful guidance for the regional application of geostationary 3D winds.

1. Introduction

Existing numerical weather prediction (NWP) adequately depicts large-scale background features of extreme weather events [1], but is limited by complex dynamic/physical processes and insufficient observations [2], so its spatiotemporal refined forecasting capability for extremes (e.g., the Zhengzhou “7.20” rainstorm) is restricted [3,4]. In particular, China Meteorological Administration (CMA) Fengyun (FY) geostationary satellite atmospheric motion vectors (AMVs) provide quasi-real-time mid- to upper-level atmospheric state data and have become a routine NWP data source that positively influences large-scale backgrounds in global and regional NWP [5,6,7,8]. However, AMV retrieval depends on the accuracy of cloud detection and height assignment, and its spatiotemporal error characteristics are complex [9,10,11,12,13,14], which makes representative-error estimation in real time difficult and leaves the improvement effect on quasi-real-time regional high-resolution NWP unclear [15,16]. Therefore, developing an assimilation scheme that accounts for spatiotemporal scale differences and enhances AMV usage efficiency to improve regional NWP holds significant scientific meaning and application value for advancing local complex-weather forecasting and disaster prevention and mitigation.

Initially, AMVs are derived by tracking clouds and moisture gradients in geostationary imagery and are used mainly in the tropics and mid-latitudes, whereas polar orbiters serve high latitudes [17,18]. Assuming that AMVs represent horizontal and vertical means of real winds [19], by introducing high-vertical-resolution satellite observations to strengthen cross-validation of AMVs in assimilation, the difficulty of estimating AMV systematic error can be indirectly reduced, and the generalized application level of overall satellite observations is significantly enhanced, so 3D schemes that fuse AMVs and hyperspectral satellite observations receive wide attention [17,20,21]. For example, introducing high-vertical-resolution wind profiles from the European Space Agency (ESA) Aeolus Doppler wind lidar (DWL) notably improves global NWP wind fields [22] and tropical cyclone forecasts [23]; introducing high-vertical-resolution observations from the CMA FY3D Microwave Humidity Sounder (MWHS-II) and/or FY4A Geostationary Interferometric Infrared Sounder (GIIRS) positively affects global NWP temperature, humidity, and winds [24] as well as tropical cyclone forecasts [25]. However, current limitations of AMVs and/or satellite hyperspectral observations in cloudy regions [9,20,26,27], together with nonlinear approximations in assimilation and conflicts with model-resolvable scales [21,28,29,30,31], highlight the necessity—beyond new satellite technologies [32]—of developing suitable AMV application schemes to address complex regional weather challenges [17].

Three-dimensional variational (3DVar) assimilation is currently applied in regional high-resolution models of every NWP center for its efficient multi-platform observation merging [33,34]. It remains challenged by background error covariance accuracy, model error, strong atmospheric nonlinearity, and difficulty in estimating representative errors of unconventional observations [35,36]. Specifically, advantages of FY geostationary AMV Var assimilation in large-scale systems [5,6,7,8] and its deficiencies in meso- to small-scale forecasts [15,16] indicate that current Var representative-error estimates, which treat different AMV data as a single observation type, underestimate spatiotemporal differences among channels and/or variables. Thus, solely adjusting AMV representative errors to raise observation usage in regional high-resolution Var assimilation, while underestimating spatiotemporal errors among different AMVs, yields limited improvement in forecasting regional complex weather events.

Early real-time scattered nudging assimilation (also known as four-dimensional data assimilation or FDDA) of NESDIS GOES winds shows small yet stable positive impacts on mesoscale NWP analyses and forecasts [37]. Nudging offers low computational cost and few parameters versus four-dimensional variational and ensemble Kalman filter [38,39,40,41], yet it updates NWP local states independently using compared observation [42,43] and remains sensitive to observation density [44]. FDDA receives wide attention in multi-scale NWP models [45,46] and high-frequency updating models with massive observations [47,48]. Limited by existing frameworks, the effectiveness of FDDA schemes with geostationary AMVs for regional complex weather and their comparison with Var schemes remain to be investigated.

Overall, FY4A AMVs exhibit high temporal but low spatial frequency with significant inter-channel differences [49,50], while neither 3DVar nor FDDA accounts for this multiscale error structure. Especially, recent study has reported 3DVar assimilation of FY4A AMVs yields limited forecast skill of the “7.20” event [16], indicating that the still-inefficient use of AMVs at finer resolution and the sensitivity of their assimilation across spatial scales are under explored. To fill this gap, by combining the three-channel merged AMVs (3D winds hereafter) with a multi-scale (12, 4, and 1 km) NWP model, the NFV scheme updating the large-scale forcing of finer 3DVar is designed to enhance AMV usage efficiency. Against the Zhengzhou “7.20” event nowcasting, the isolated impacts of Nudging versus 3DVar are quantified through ablation and NFV is further comprehensively evaluated, aiming to provide potential operation guidance. The texts are arranged as follows: Section 2 describes the data and model, Section 3 describes the NFV method, Section 4 describes the experimental design, Section 5 describes the results, and the discussion and conclusion are presented in Section 6 and Section 7, respectively.

2. Data and Model

2.1. Data

2.1.1. Observation

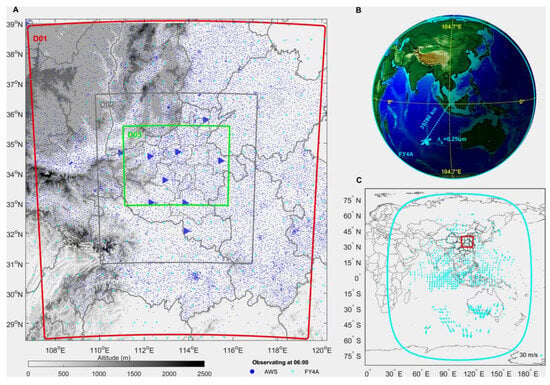

Based on FY4A AMVs [49,50] from the CMA National Satellite Meteorological Center (NSMC), horizontal winds of low-level water–vapor ch09 (6.95 μm), high-level water–vapor ch10 (7.42 μm), and infrared ch12 (10.7 μm) are quality controlled and merged into an FY4A 3D wind profile, which has 3 h and around 48 km resolution and is used for assimilation and forecasting. It is distributed over northern Henan and surrounding cloudy areas at UTC 06:00 before the Zhengzhou “7.20” rainstorm (Figure 1A, cyan crosses). FY4A carries the Advanced Geostationary Radiation Imager (AGRI, on-orbit parameters in Figure 1B) with 14 channels covering 0.5~15 μm at 1 h resolution; AMVs are derived from its successive images, and the ch09 cylindrical projection and study area are shown in Figure 1C. Besides AMVs, FY4A black-body brightness-temperature (TBB) product [51] at 1 h and 4 km resolution is collected to verify assimilation impacts on mid- to upper-level TBB forecasts.

Figure 1.

(A). Domains and observations: mesoscale (12 km; red box, D01), small-scale (4 km; gray box, D02), and microscale (1 km; green, D03); FY4A quality-controlled 3D wind vectors at 06:00 UTC (cyan plus), automatic weather stations (AWS, blue dots), and S-band Doppler radar (blue sector, azimuth −45°); terrain (shaded; m). (B). FY4A on-orbit schematic and key parameters: field of view (cyan circle), sub-satellite point (yellow dashed cross), satellite-earth distance, and core wavelengths of 3D wind observations. (C). On equidistant cylindrical projection: FY4A coverage at 06:00 UTC (cyan ellipse), ch09 AMV winds (vectors; m/s), and D01 location (red box).

Moreover, the surface automatic weather station observation (AWS), CMA Land Data Assimilation System reanalysis datasets (CLDAS), and nine S-band Doppler Radar data (Figure 1A) derived from the CMA Henan Meteorological Bureau are collected for nowcasting indicator verification over the D03 domain. The AWS with a resolution of around 0.1° and 1 h intervals accounts for hourly rainfall evaluation, while regarding AWS’s discontinuities, the CLDAS with a resolution of around 0.05° and 1 h intervals accounts for total rainfall evaluation. The nine radar reflectivity data with bin-width lengths of around 230 m, 6 min intervals, and 11 elevation numbers are firstly quality controlled with various clutter and range suppression checks for each radar, then remapped with 0.01° grids for each elevation number, and finally, the maximum reflectivity across 11 elevation numbers for each grid is obtained as the composite reflectivity (briefed as CR hereafter), which accounts for the convection evaluation.

2.1.2. Forcing

The atmospheric forcing datasets are collected from the first-generation global atmospheric/land-surface reanalysis project (CRA40), which has a resolution of 34 km and 64 pressure levels, and 6/3 h intervals for the atmospheric/surface layer [52,53]. Meanwhile, the Global Land Data Assimilation System reanalysis (GLDAS, version 2.1), derived from National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) with a resolution of 0.25°, 3 h, and 4 layer (https://ldas.gsfc.nasa.gov/gldas/, accessed on 19 January 2026), is used to drive the Noah LSM of WRF. The U.S. Geological Survey’s Shuttle Radar Topography Mission 3-arc-second Digital Elevation Model datasets (https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/lpcloud-srtmgl3-003, accessed on 19 January 2026) and the NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer Land Cover Type Yearly L3 Global 500 m SIN Grid V061 datasets (MCD12Q1 in 2021, version 6.1; https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/lpcloud-mcd12q1-061, accessed on 19 January 2026) are used as the WRF’s underlying terrain and land cover, respectively. Moreover, due to the computation and storage limits, the National Centers for Environmental Prediction’s FNL (Final) Operational Global Analysis dataset with a resolution of 0.25°, 6 h, and 27 layer (https://gdex.ucar.edu/datasets/d083002/dataaccess/#, accessed on 19 January 2026), is collected to assemble the 3DVar’s background errors between 12 h and 24 h lead forecasts using the month-long initial-time-differed forecasts (known as the NMC method).

2.2. WRF

The WRF model (version 3.9.1) is employed in this study to simulate the regional rainstorm event. The model uses nested domains with one-way feedback that only considers the feedback from outer to inner domains. The outer and middle domains are both centered at 113.45°E, 33.85°N, and consist of 100 × 100 grids at 12 km resolution and166 × 160 grids at 4 km resolution, respectively, and the inner domain is centered around Zhengzhou city, and consists of 301 × 201 grids at around 1 km resolution. The model includes 51 levels with 11 levels below 1 km, and the model top pressure is 50 hPa. The time integration step is 30 s.

For the outer domain, the Kain–Fritsch (KF) convection scheme [54] is used, while convection is turned off in the inner domain. Other physical processes are modeled using the same schemes for all domains: the Thompson scheme for cloud microphysics [55], the Yonsei University (YSU) scheme for boundary layer physics [56], the Rapid Radiative Transfer Model (RRTMG) scheme for both long-wave and short-wave radiation physics [57], the Monin–Obukhov similarity scheme for surface physics [58], the Noah Land Surface Model (LSM) scheme for land surface physics [59], and the Unified Canopy Model (UCM) scheme for canopy physics [60].

2.3. Reproducibility

2.3.1. Multichannel AMV Fusion

Firstly, all FY4A AMVs with bad pixel identifier (i.e., whose code exceeds 2 [49,50]) are discarded. Then, these quality-controlled AMVs of all channels at the identical horizontal point “a”, without duplication or at varying heights/pressures, are merged to constitute the atmospheric profile of point “a”. However, due to the position drifting of FY4A AGRI, e.g., 1-h horizontal drift positioning could reach about 1.3 pixel that accounts around 4-km [12,61], the 3-h AMV horizontal position drifting could be 12-km. In this study, “a” is simply assumed to be a 12-km × 12-km box centered around the predefined grids of AMV, then all gridded profiles (or 3D winds) could be achieved, whose horizontal resolution is around 48-km (i.e., AMV resolution as 60-km minus the 3-h drifting as 12-km). This aligns consistently with most previous 3D fusing schemes using AMVs [17,20,21].

2.3.2. Quality Control Check

Raw 3D wind observations are assigned with “QCFlag” value ranging from 21 to 218 (i.e., QCC), based on 18-kind tests that account for various spatial and physical consistency checks against specific background (for details, refer to https://www2.mmm.ucar.edu/wrf/users/docs/user_guide_V3/user_guide_V3.9/users_guide_chap7.html#obsNamelist, accessed on 3 January 2026). This allows for the various quality control flags to be additive, yet permits the decomposition of the total sum into constituent components, while smaller QCC indicates stricter check. Notably, the QCC of objective analysis (briefed as OA hereafter) is conducted over D01 using OBSGRID of WRF, and QCC of 3DVar is conducted over D03 using OBSPROC of WRF.

2.3.3. Key Nudging Parameters

The Nudging scheme of WRF uses the offline OA of OBSGRID to achieve temporal sequence flow of analysis and observation increments for further initialization, then, the online FDDA is used to nudge the observation incremental flow for adjusting forecasts; the empirical offline (OA) and online (FDDA) parameters (detailed in Section S1.1) in WRF are shown in Table 1. The choice standard of parameter values is mostly based on WRF’s recommendation that aligns consistently with many previous studies [42,43,46,47,48].

Table 1.

Main parameters of Nudging used in this study.

3. Method

3.1. Assimilation

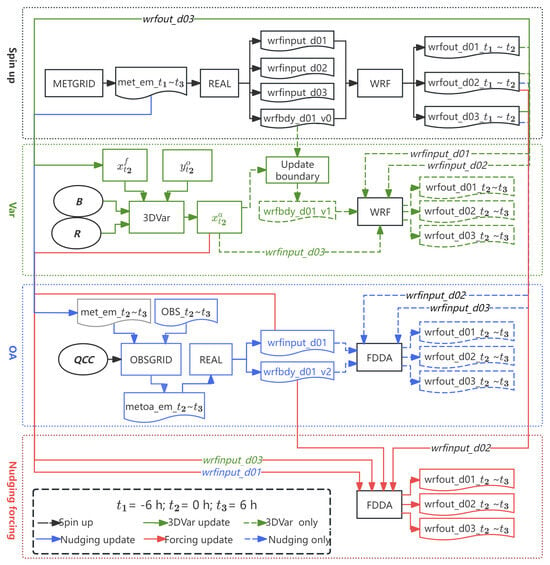

As shown in Figure 2, the NFV scheme is based on WRF 3DVar (green solid line) for high-resolution assimilation [62], and is driven by large-scale Nudging through OA (blue solid line) and FDDA (red solid line), completed in four steps.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the NFV short-range forecast scheme and its main modules (solid lines). Spin-up denotes a cold-start forecast at −6 h (). 3DVar denotes observation assimilation over D03 at 0 h (), with and . OA denotes successive objective analyses (e.g., OBSGRID’s Cressman analysis) with observation and quality control checks (QCC) during 0~6 h (~). Forcing updating denotes FDDA analysis and forecast during ~, combining the 3DVar analysis and nudging initialization at . Note that METGRID, REAL, and OBSGRID details are available at the latest WRF archive as https://github.com/wrf-model (accessed on 19 January 2026).

First, use forcing data to drive WRF for cold-start spin-up; met_em* files and the −6~0 h forecast (~) are generated. Second, Var update uses the 0 h () spin-up forecast as background (), ingests observations (), and updates the background using background and observation covariance (i.e., and ) to yield an analysis . Third, OA update uses the 0~6 h (~) spin-up met_em* sequence as background, continuously ingests concurrent observations (OBS_~) with QCC, and produces OA sequence (metoa_em*) that initializes new D01 initial and boundary conditions. Finally, in Nudging forcing, the spin-up forecast and supply initial conditions for D02 and D03, respectively; WRF FDDA continuously updates the D01 fields, yielding the NFV 0~6 h (~) forecast. Nudging in NFV is detailed in Section S1.1 of the Supplements.

Note that Var and Nudging run separately over different domains and simultaneously without extra cost; independent forward integrations with spin-up data provide single-scheme ablation forecasts in NFV (Figure 2, dashed lines). Observations with QCC > 210 are rejected in both Nudging and Var, constituting observation quality control for FY4A 3D winds. Quality-controlled observations are subsequently used for verification and evaluation. In 3DVar, adopted the NMC method using FNL data-driven forecasts, chose the global sounding climatological errors, and the observation innovation as observation-minus-background (OMB) greater than is rejected.

3.2. Verification

To verify the impacts of Nudging and Var in the NFV method, linear fitting and multiple objective metrics are applied in observation space. These metrics include root-mean-square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), correlation coefficient (CC), and goodness of fit (R2) (detailed in Section S1.2.1). Element-wise comparisons are performed at FY4A observation points for observations, background, and analysis. Differences in background between OA and 3DVar domains and resolutions are considered. In model space, primary features of analysis minus background (AMB) for observed variables are compared.

To verify NFV impacts on forecasts, linear fits and metrics (as RMSE, MAE, CC, and R2) for FY4A 3D winds and forecasts are compared. By using the Radiative Transfer model for TOVS (RTTOV, v14) [63], the forecast TBBs are retrieved (see Section S1.2.2) and further compared with FY4A TBB data. Especially, based on the fine observations as AWS, CLDAS, and Radar CR, comprehensive validations as the probability density function (PDF) fitting, the Roebber skills [64], and the Method for Object-based Diagnostic Evaluation (MODE) metrics [65] are conducted for the key nowcasting indicators over the D03 domain, i.e., short-duration heavy rain (briefed as SHR hereafter), 6 h rainstorm, and severe convection. Note that SHR is defined as the hourly rainfall exceeding 25 mm, 6 h rainstorm is defined as rainfall exceeding 50 mm, and severe convection is defined as CR exceeding 45 dbz. To ensure an equitable verification, the forecasts and observations are all regridded into identical grids of 0.01° with bilinear interpolation. Also, the convolution radius is twice the grid resolution for SHR and 6 h rainstorm, while it is 20 times the grid resolution for severe convection.

Finally, spatial differences between Nudging and Var forecasts, such as RMSVD, VCC, and VR2 (see Section S1.2.1), are compared. Rotunno–Klemp–Weisman (short for RKW hereafter) environmental conditions [66,67] are analyzed to clarify how FY4A 3D wind assimilation influences NFV nowcasting through unobserved mesoscale systems and thermodynamic conditions during this rainstorm.

4. Experiment

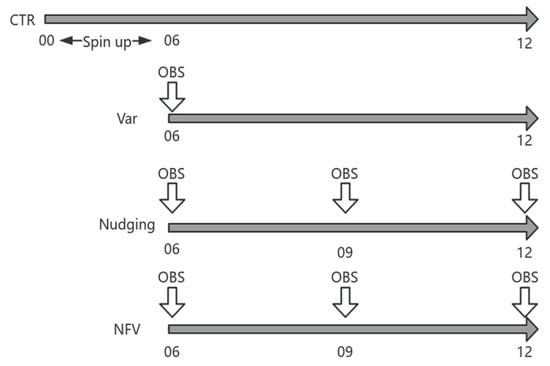

The control run (CTR) is initialized at 00:00 UTC 20 July 2021 with a subsequent 12 h forecast, its 0~6 h forecast serves the 6 h spin-up of assimilation experiments, while its 6~12 h forecast is in the range of 00:00~12:00 UTC 20 July 2021 (Figure 3), covering the whole Zhengzhou “7.20” rainstorm period, then serves the nowcasting comparison of assimilation experiments. Var that assimilates FY4A 3D winds at 06:00 over D03 region serves as the operational 3DVar assimilation, which is similar to a nearby AMV assimilation study [16], but to a finer scale using sounding assimilation entry. Nudging that assimilates 3 h interval FY4A 3D winds from 06:00 to 12:00 over the D01 region serves as the real-time large-scale adjustments. NFV that updates the 3DVar’s forcing using these adjustments serves as the hybrid multi-scale assimilation.

Figure 3.

Data flow of the experiments. OBS = observation.

As shown in Table 2, CTR supplies the background for assimilation. In NFV, FDDA (D01) and 3DVar (D03) assimilate all FY4A 3D wind variables (P, T, U, V); quality control applies QCC and R (see Section 2.3.2 and Section 3.1), and serves as the reference. Experiments Var and Nudging are obtained by removing FDDA and 3DVar assimilation from NFV, respectively, thus providing a mutual method ablation of NFV.

Table 2.

Description of experiments.

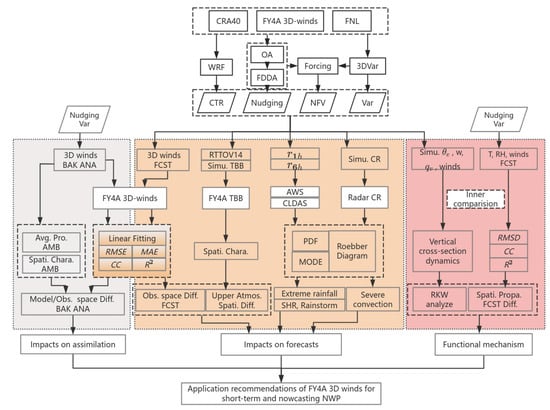

The research flow comprising the main three steps is shown in Figure 4. First, multi-index comparisons of observation, background, and analysis in observation space from Var and Nudging simulations quantify observational impacts within NFV. Second, verification of forecasts against observations in observation space, comparison of RTTOV14 retrievals with FY4A observations, and precipitation and convection diagnostics identify the principal forecast influenced by FY4A observations. Third, analysis of forecast error propagation and differences in RKW environmental conditions between Var and Nudging outputs elucidates the synoptic mechanisms by which FY4A observations induce forecast differences. Recommendations for the numerical nowcasting application of FY4A AMVs are ultimately provided.

Figure 4.

The flowchart of this study. BAK = background. ANA = analysis. FCST = forecast. AMB = analysis minus background. CR = composite reflectivity.

5. Results

5.1. Impacts on Assimilation

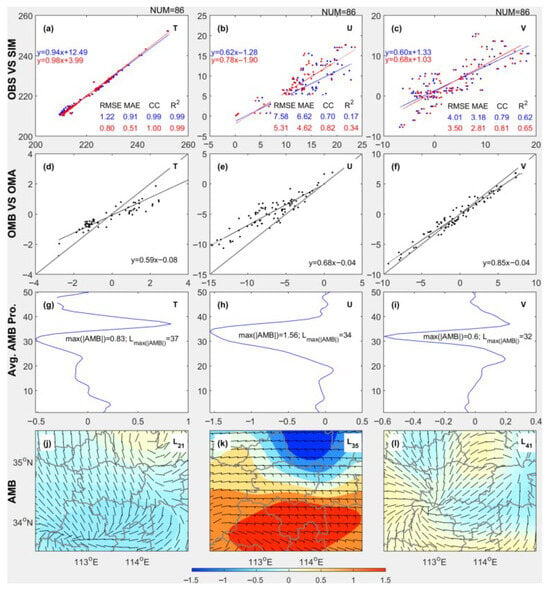

5.1.1. 3DVar

Figure 5 presents the combined comparison of observations, background, and analysis for 3DVar. For the linear fit between OBS and SIM, 86 full-observation pairs (T, U, and V) enter assimilation; ANA fit coefficients are closer to 1 than BAK, while RMSE and MAE decrease and CC and R2 increase (Figure 5a–c). For linear fits of OMB and OMA, coefficients are both below 1 (Figure 5d–f). These indicate clear positive impacts of 3DVar assimilation on T, U, and V in observation space. For domain-averaged AMB profiles, maximum absolute values of T, U, and V are 0.83 K, 1.56 m/s, and 0.6 m/s, respectively, concentrated between model layers 30~40 (Figure 5g–i). AMB increments for temperature and wind are weak at layer 21 and 40 but relatively strong at layer 35, showing overall warm-easterly characteristics (Figure 5j–l). This indicates that assimilation significantly adjusts the mid-upper levels (around 400~200 hPa) of BAK, exhibiting divergence with lower-level cooling, upper-level warming, and southeast wind.

Figure 5.

Comparison of observations (OBS) and simulations (SIM) over D03 at 06:00 UTC for 3DVar assimilation. (a–c) Linear fits of FY4A OBS (x-axis) versus BAK (blue) and ANA (red) for T, U, and V in observation space; RMSE, MAE, CC, and R2 are displayed. (d–f) Linear fits of OMA (x-axis) and OMB for T, U, and V in observation space; gray diagonal indicates assimilation equivalence. (g–i) Vertical profiles of domain-averaged AMB for T, U, and V in model space; maximum absolute AMB and corresponding layer are marked. (j–l) AMB at model layers 21, 35, 41: temperature (shaded) and vector wind; one barb denotes 4 m/s.

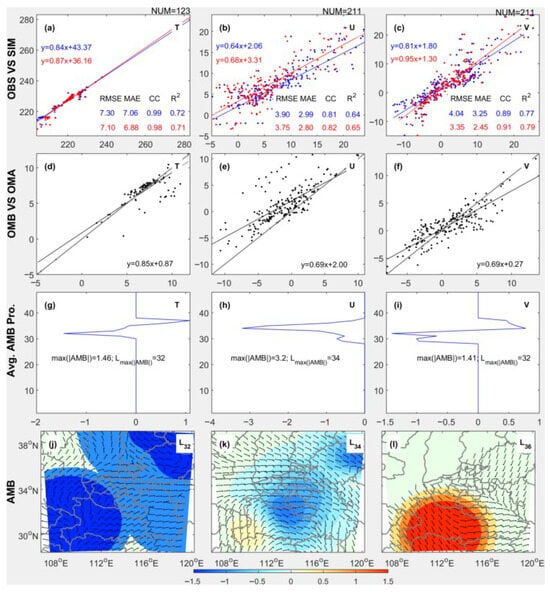

5.1.2. OA

Figure 6 compares OA observations with background and analysis at 06 UTC. For OBS-versus-SIM linear fits, 123 T, 211 U, and 211 V samples are assimilated; ANA fit coefficients improve and RMSE and MAE decrease (Figure 6a–c). OMB and OMA linear fits both yield coefficients below one (Figure 6d–f), indicating clear positive OA impacts on T, U, and V in observation space. Domain-averaged AMB profiles show maximum absolute values of 1.46 K, 3.2 m/s, and 1.41 m/s for T, U, and V, respectively, all concentrated between model layers 30–40 (Figure 6g–i). AMB exhibits cold anomaly, easterly wind, and warm anomaly at layers 32, 34, and 35, respectively (Figure 6j–l). These results demonstrate that OA significantly adjusts the mid-upper levels (around 400~200 hPa) of BAK, characterized by lower-level cooling, upper-level warming, and southeast-wind enhancement.

Figure 6.

As in Figure 5, but for OA over D01 at 06:00 UTC. (a–c) Linear fits of FY4A OBS (x-axis) versus BAK (blue) and ANA (red) for T, U, and V in observation space; RMSE, MAE, CC, and R2 are displayed. (d–f) Linear fits of OMA (x-axis) and OMB for T, U, and V in observation space; gray diagonal indicates assimilation equivalence. (g–i) Vertical profiles of domain-averaged AMB for T, U, and V in model space; maximum absolute AMB and corresponding layer are marked. (j–l) AMB at model layers 32, 34, 36: temperature (shaded) and vector wind; one barb denotes 4 m/s.

OA at 09 and 12 UTC performs similarly to 06 UTC, with slightly increased observation counts (see Figure S1). Compared with 3DVar, OA assimilates significantly more observations. Mid-upper AMB patterns resemble those in 3DVar but are markedly stronger in OA. Thus, within NFV, OA continuously adjusts D01 mid-upper temperature and wind toward observations, exhibiting persistent pronounced divergence increments, whereas 3DVar effectively improves D03 mid-upper fields with weaker divergence increments.

5.2. Impacts on Forecast

5.2.1. Upper Atmosphere

Comparison with FY4A Winds

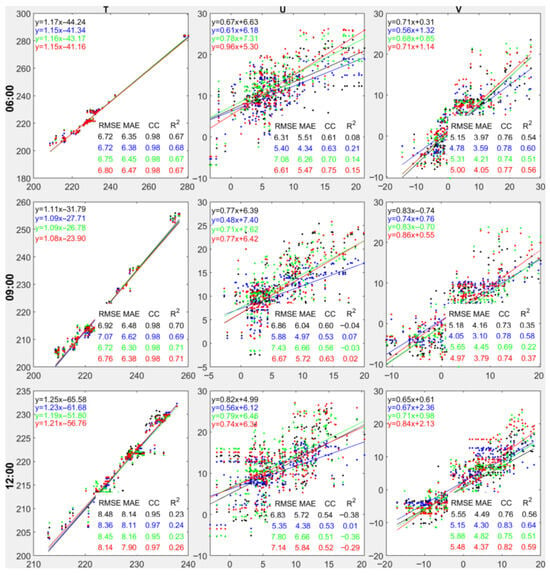

Fitting between forecasts and FY4A 3D winds are shown in Figure 7. For T, linear coefficients slightly exceed 1 and intercepts are large, indicating systematic forecast deviation that is most pronounced at 12 UTC. For U and V, coefficients are below 1, indicating adjustment toward observations.

Figure 7.

Linear fits in D03 during 06:00~12:00 UTC between FY4A 3D winds (x-axis) and forecasts (CTR, Nudging, Var, NFV in black, blue, green, red) for T, U, V, with RMSE, MAE, CC, R2 shown.

For T, fit coefficients of all assimilation experiments are closer to 1 than CTR, indicating positive assimilation impacts. However, inter-experiment differences in RMSE and MAE remain below 0.5 K, and those in CC and R2 below 0.03, revealing limited improvements likely linked to strong upper-level signals such as temperature lapse rates. For U and V, Nudging yields the lowest linear fit coefficients, RMSE and MAE at every forecast time, whereas NFV shows the opposite. This indicates that reduced vector-wind errors in the upper atmosphere demonstrate Nudging’s greater positive impact through increased FY4A 3D wind assimilation entries, yet its spatial linear-fit capability is significantly weakened. NFV’s contrasting performance implies highly nonlinear multi-scale interactions of upper-level vector winds.

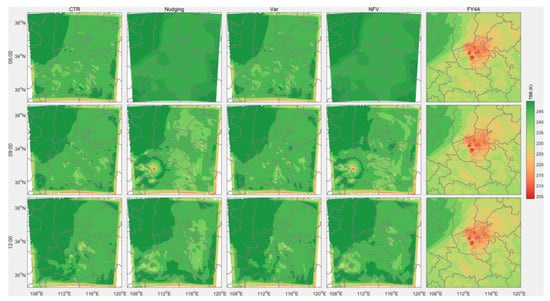

Compared with FY4A TBB

Due to the limited retrieval resolution of the RTTOV14 model, forecasts from the coarser D01 domain are used for RTTOV14 simulations and compared with FY4A ch09 TBB (Figure 8). Although significant magnitude differences exist, the northeast–high–southwest–low TBB pattern in all experiments agrees well with observations. Notably, compared with CTR and Var, Nudging and NFV better reproduce the observed patchy low-value regions at 09 and 12 UTC.

Figure 8.

Comparison of TBB retrievals of each experiment in D01 with FY4A ch09 TBB during 06:00~12:00 UTC.

Overall, FY4A wind assimilation exerts distinct positive impacts on upper-level forecasts. On the one hand, in the D03 FY4A wind observation space, error reduction and increased correlation are seen for Nudging, enhanced vector-wind linear fit for NFV, and intermediate performance for Var. On the other hand, in D01 FY4A ch09 TBB, Nudging and NFV exhibit superior spatial consistency. These likely linked to greater observation ingestion in Nudging and multi-scale interactions across different domains.

5.2.2. Rainfall

Probability Density Distribution

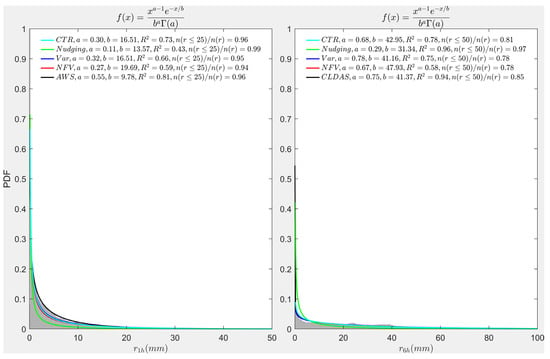

Figure 9 shows the gamma (Γ)-distribution fits of (about 3.6 × 107 samples) and (about 6 × 106 samples) within 1000 bins for all data, whereas all R2 exceeds 0.43, indicating consistent distributions. The shape parameter for stays below 0.5 for all data, revealing extreme heterogeneity, whereas for exceeds 0.6 except for Nudging, implying more uniform coverage. For and , Nudging yields the smallest a and the highest light-rain fraction, denoting highly uneven light precipitation, while NFV exhibits the largest scale parameter and the lowest light-rain fraction, indicating the greatest mean intensity and frequent heavy rainfall.

Figure 9.

Gamma-distribution fits of (left) and (right) for all data over D03; shaded areas show observed scatter. Note: observations refer to AWS and CLDAS data.

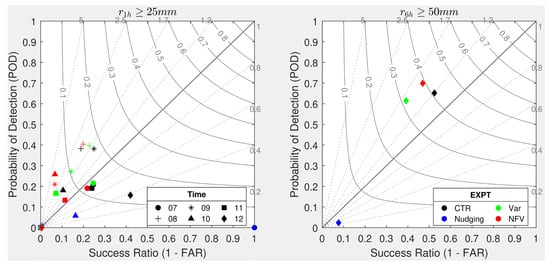

Roebber Skill Scores

Figure 10 compares comprehensive precipitation skills. For SHR and rainstorm events, most points lie on the upper-left of the Roebber diagram, indicating evident over-forecasting. For SHR in , except at 08 UTC, the critical success index (CSI) never exceeds 0.1, so skill differences among experiments are indistinguishable. At 08 UTC, NFV yields the highest probability of detection (POD), yet Var attains the highest success rate (SR) and CSI and a BIAS closest to 1, giving the best skill. Consequently, Var ranks first, followed by NFV, CTR, and Nudging last. For rainstorm in , all experiments except Nudging outperform those for short-duration heavy rain. Specifically, the highest POD is approximately 0.7 (NFV), the highest SR is approximately 0.5 (CTR), the highest CSI is approximately 0.4 (CTR and NFV), and the BIAS is approximately 1.2 (CTR). Thus, CTR exhibits the best skill, followed by NFV, then Var, and Nudging is the worst.

Figure 10.

Roebber diagram comparison of forecast precipitation in D03; (left): hourly SHR during 07–12 UTC, (right): 6 h rainstorm at 12 UTC. Thick gray marks the 1:1 (POD = SR) no-bias line; thin solid and dashed gray lines indicate CSI and BIAS references.

Overall, SHR skill (CSI ≤ 0.2) is markedly lower than rainstorm skill (CSI > 0.3), indicating low skill or poor verifiability. Integrating both types, NFV shows consistent performance, CTR and Var exhibit large uncertainty, and Nudging performs worst.

SHR, Extremes and Rainstorm

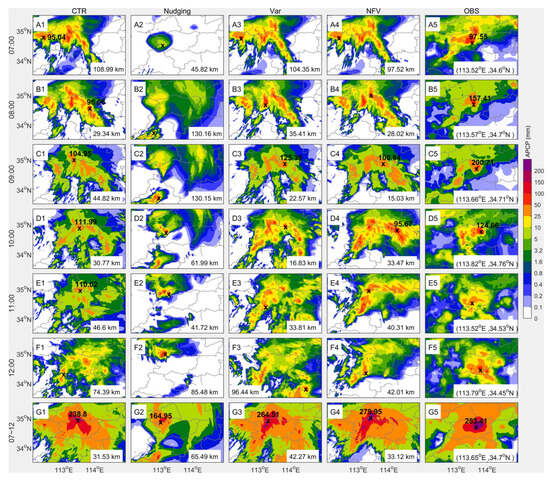

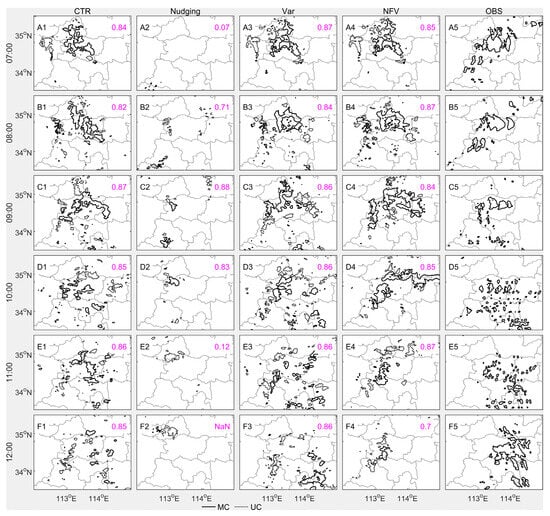

During 07~12 UTC, comparisons of forecast and observed precipitation are shown in Figure 11A1–F5. Observations indicate that SHR regions remains over Zhengzhou (Figure 11A5–F5). From 07~10 UTC, an extreme point (“x”, ≥ 95 mm) is observed near downtown Zhengzhou (around 34.6°N, 113.8°E), exceeding 200 mm at 09 UTC (Figure 11C5), after which the SHR weakens, consolidates, and slightly extends southeastward.

Figure 11.

Comprehensive comparison of precipitation forecasts and observations in D03. Panels (A1–F1,A2–F2,A3–F3,A4–F4,A5–F5) show at 07~12 UTC 20 July for CTR, Nudging, Var, NFV, and OBS; “x” marks extreme points (values shown if ≥95 mm). The observed extreme point locations of AWS in (longitude, latitude) are shown for row 5, while the forecast distances of extreme point (in km) compared to observation are also shown in rows 1–4. Panel (G1–G5) is as (A1–F5) but for at 12 UTC compared to CLDAS.

During 07~10 UTC, CTR, 3DVar, and NFV produces similar SHR patterns, all larger than observed; the extreme point “x” is shifted north by CTR, while Var and NFV are closest to observations (Figure 11A1–D1,A3–D3,A4–D4). At 09 UTC, Var’s extreme reaches 125 mm (Figure 11C3); afterward, their positions diverge and areas shrink below those observed. Nudging’s SHR area is markedly smaller, confined to western Zhengzhou (Figure 11A2–F2).

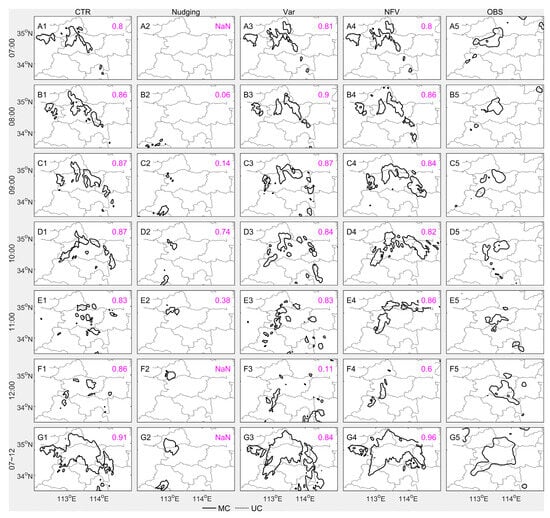

As shown in Figure 12, the MODE total interest (TI) for SHR is valid only at 10 UTC for Nudging (0.74). CTR, Var, and NFV achieve TI above 0.8 during 07:00~11:00 UTC, indicating good spatial features, but Var’s TI drops sharply to 0.11 at 12 UTC, revealing pronounced spatial error.

Figure 12.

Same as Figure 11. Black contours in (A1–F1,A2–F2,A3–F3,A4–F4,A5–F5) outline MODE objects with threshold ≥ 25 mm; solid and dashed lines denote matched (MC) and unmatched (UC) objects, with magenta numbers giving total interest (TI). (G1–G5) is as (A1–F5) but for at 12 UTC with object threshold ≥50 mm.

Figure 11G1–G5 shows that observed precipitation at the Zhengzhou center reaches 283 mm; NFV simulates about 280 mm but slightly north, while other experiments produce maxima below 250 mm and positions shifted west. MODE TI for rainstorm (Figure 12G1–G5) indicates NFV attains the highest TI (0.96), demonstrating the best spatial pattern among all schemes. Nudging exhibits missed events, and Var shows evident false alarms.

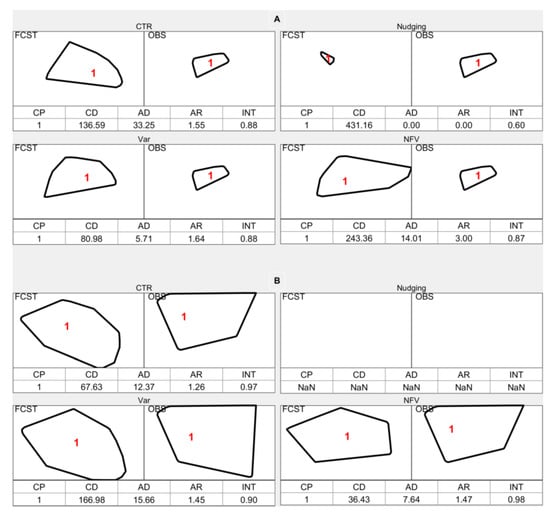

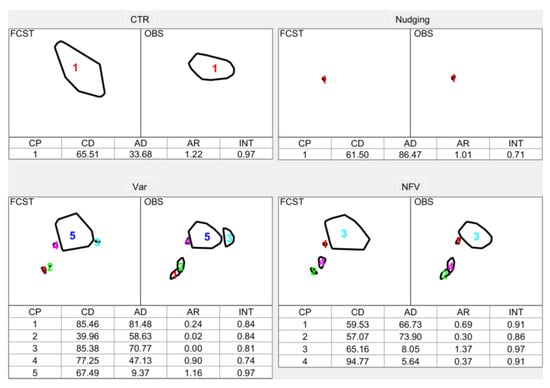

Spatial Object Characteristics

To examine spatial differences in forecast precipitation, multiple geometric attributes of MODE’s matched object cluster pairs (CP) are compared (Figure 13). The 10 UTC SHR event, having the most cases with total interest TI > 0.7 (Figure 11D1–D4), is selected. For SHR (Figure 13A), Nudging shows the smallest angle difference (AD), the smallest area ratio (AR), and the largest centroid distance (CD), giving the lowest interest (0.6). CTR, Var, and NFV yield almost equal interest (0.88); CTR has AR closest to 1, whereas Var has the smallest CD. For rainstorm (Figure 13B), CTR and NFV share nearly equal interest (0.98), higher than Var (0.90). AR differences among the three are small, but NFV’s CD and AD are markedly smaller than those of CTR and Var.

Figure 13.

Comparison of MODE-matched object cluster pairs between forecast ((left), FCST) and observation ((right), OBS). (A): 10 UTC SHR; (B): 6 h rainstorm. CP = cluster pair, CD = centroid distance, AD = angle difference, AR = area ratio, INT = interest. The colored numbers indicate the indexes of CP.

Overall, except for Nudging, all experiments exhibit evident overall false alarms yet missed extremes, with large spreads among nowcasting indicators like SHR, extremes, and rainstorm. Nudging keeps the large-scale rainfall pattern but with poor skills. Var yields the largest extreme rainfall at 09 UTC, but its spatial pattern departs sharply in time and space. NFV places the forecasted extremes closest to observations and shows the smallest spatiotemporal deviations across all nowcasting metrics, delivering more robust skill. These assimilation disadvantages/advantages are likely linked to differing small-scale system development during the period.

5.2.3. Convection

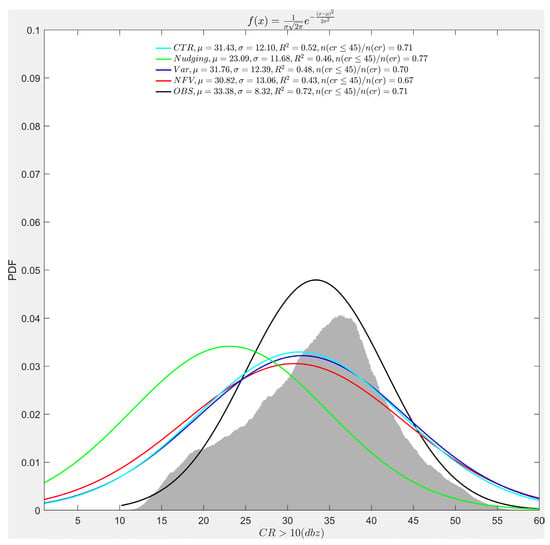

Probability Density Distribution

Figure 14 shows differentiated Gaussian distribution fits of CR (about 3.6 × 107 samples within 1000 bins), and goodness of fit exceeds 0.46 for all data except NFV. Except for Nudging, all other PDF centers (μ) lie around 31~33 dBZ, denoting widespread stratiform features. PDF’s standard deviation (as σ) is around 12~13 dBZ for all data, clearly above the observed 8 dBZ, implying broader CR ranges in forecasts. NFV exhibits the lowest weak-CR (<45 dBZ) fraction (0.67), signifying the strongest convective development among all datasets.

Figure 14.

As in Figure 9, but for Gaussian PDF of CR; shaded area shows observed scatter.

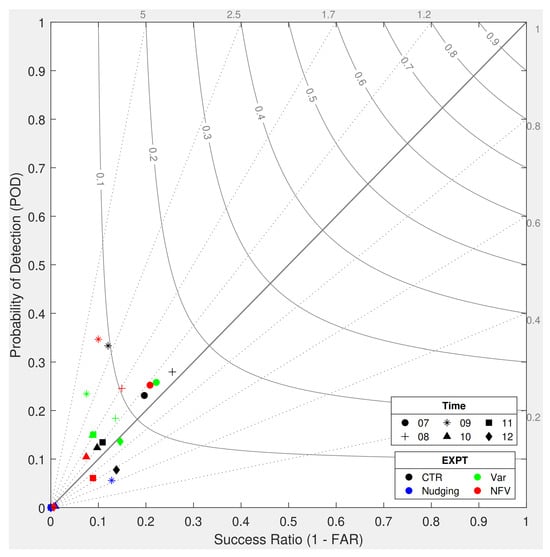

Roebber Skill Scores

Figure 15 compares composite skill for severe convection (CR ≥ 45 dBZ). Most points lie in the lower-left of the Roebber diagram; except for at 07 and 08 UTC, CSI never exceeds 0.1, indicating low skill. At 07 UTC, Var and NFV are comparable and slightly better than CTR; at 08 UTC, CTR outperforms NFV, while Var shows almost no skill. Thus, severe convection skill of Var is highly uncertain.

Figure 15.

As in Figure 10, but for composite skill of CR ≥ 45 dBZ during 07~12 UTC.

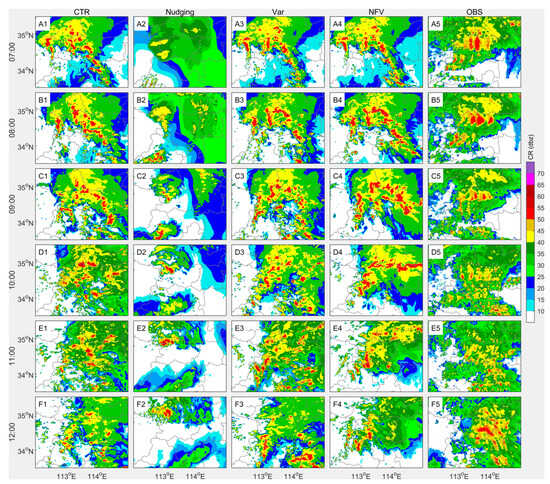

Severe Convection

Figure 16 compares CR among experiments and observations. Observations show CR ≥ 45 dBZ mainly over Zhengzhou (Figure 16A5–F5); during 07:00~10:00 UTC, two zebra-striped bands persist, shift slightly southward, shrink markedly, then intensify and move eastward during 11:00~12:00 UTC. In Nudging, the two bands are evident but smaller and displaced (Figure 16A2–F2). CTR, Var, and NFV overestimate coverage, most pronounced in NFV. During 07:00~09:00 UTC, their patterns are similar, then diverge.

Figure 16.

As in Figure 11, but for CR forecasts versus S-band radar CR observations over D03. Panels (A1–F1,A2–F2,A3–F3,A4–F4,A5–F5) show CR at 07~12 UTC 20 July for CTR, Nudging, Var, NFV, and OBS.

As shown in Figure 17, for convective CR, MODE TI is valid (>0.7) for Nudging only during 08:00~10:00 UTC, whereas other experiments exceed 0.7 at all times, indicating good spatial patterns. Var’s TI averages around 0.86, slightly better than CTR and NFV.

Figure 17.

As in Figure 12, but for CR forecasts versus S-band radar CR observations over D03. Black contours in (A1–F1,A2–F2,A3–F3,A4–F4,A5–F5) outline MODE objects with threshold ≥ 45 dBZ; solid and dashed lines denote matched (MC) and unmatched (UC) objects, with magenta numbers giving total interest (TI).

Spatial Object Characteristics

To examine spatial differences in strong echo, geometric attributes of MODE-matched CP are compared at 08 UTC (Figure 18). The CP counts for Var and NFV exceed others, indicating highly non-uniform shapes and positions. Among the largest clusters, CTR (CP1), Var (CP5), and NFV (CP3) share equal interest (0.97), clearly above Nudging. NFV exhibits the smallest CD and AD, whereas Var’s AR is closest to 1.

Figure 18.

As in Figure 13, but for matched-object clusters with CR ≥ 45 dBZ at 08 UTC. The colored numbers indicate the indexes of CP.

Overall, except for weaker mean CR in Nudging, all experiments exhibit PDFs consistent with observations. For CR ≥ 45 dBZ, the fraction of all data is uniformly near 0.7, yet skill remains low with evident spatiotemporal disparities. Nudging preserves large-scale convective signatures but clearly misses developing convective zones. Although CTR, Var, and NFV share similar TI scores, NFV better maintains convective persistence, whereas CTR and Var shift southward markedly. These are closely correlated with differences in SHR, extreme, and rainstorm forecasts.

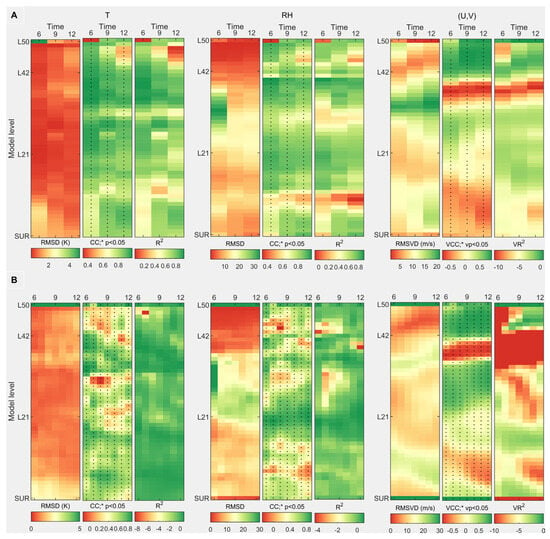

5.3. Functional Mechanism

5.3.1. Propagation of Forecast Differences

Figure 19 shows spatial RMSD, correlation coefficients, and goodness of fit for T, RH, and vector wind (U, V) between Nudging and Var in D01 and D03. In D01, maximum spatial differences of T occur at L50 of 06 UTC, then weaken and descend to L43. This is consistent with adjustment following the imposed upper-level nudging increments. RH peaks at L31 at 06 UTC and weakens afterward. Vector-wind maxima appear at L31 and spread upward/downward to L41/L23. D03 exhibits similar propagation patterns but with notably larger value, while T and RH over D03 show more local extremes for both CC and R2 when compared to those over D01, indicating the horizontal spatial pattern of both T and RH are likely affected by non-self factors or local systems. Generally, the consistent forecast difference propagation of vector wind over both D01 and D03 is more significant compared to T and RH.

Figure 19.

Temporal–vertical diffusion of RMSD, CC with significance level p, and R2 for T, RH and vector wind (U, V) between Nudging and Var is shown in D01 ((A), 3 h) and D03 ((B), 1 h).

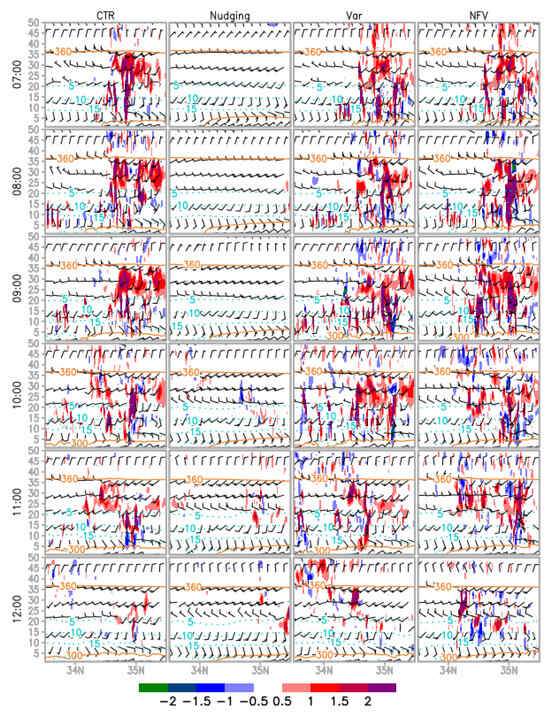

5.3.2. Evolution of Rainfall System

Under RKW maintenance theory, balanced horizontal shear within the cold pool allows deep convection to persist. At 08 UTC, strong divergence near L41 in NFV enhances suction aloft, intensifying convection north of 113.5°E (Figure 20). The associated northward-tilted vertical vorticity limits southward spreading of the low-level cold pool (), shifting rainfall northward. This could be linked to enhanced northeasterly increments introduced by Nudging at upper levels. Later, NFV’s rainband shifts westward because that weaker low-level vertical shear and convergence over the east produce weaker convection and lower precipitation efficiency. Specifically, the large-scale nudging has continuously induced the enhanced upper-tropospheric divergence (Figure 6), then it induces stronger rear-inflow jet, while the water–vapor flux convergence of the boundary layer (L1~L11) increased around 8 g m−2 s−1 (Figure S3). Then, the vertical wind shear of the boundary-to-mid layer (L1~L21) increased by around 5 s−1 (Figure S4), and cold-pool lateral spreading reduced by 15% (or 0.3° northward deviation). This causes the convective systems to move more northward and be longer lived.

Figure 20.

Vertical cross-sections along 113.5°E at 07:00~12:00 UTC for all experiments; x-axis denotes latitude, y-axis model level. Variables include vertical velocity (shaded, −2~2 m/s at 0.5 m/s intervals), horizontal wind (vectors, 1 barb represents 4 m/s), equivalent potential temperature (yellow contours, 300 and 360 K), and water–vapor mixing ratio (cyan dotted, 5~15 g/kg at 5 g/kg intervals).

6. Discussion

Although the NFV method, through simple combination of Nudging and Var, effectively improves forecasts of mid-tropospheric motion, short-duration heavy rain, 6-h rainstorm, and severe convection during the Zhengzhou “7.20” event, the extremely low verifiability of SHR and of rainfall extremes also reveals the limits of both the scheme and the observations.

Previous FY4A AMV assimilation studies with 3DVar have documented the static representativeness errors of AMV data [15] and the benefit of correcting them for forecasts longer than 12 h [16], but give no guidance on nowcast metrics such as SHR or 6-h rainstorms. And the physics-based justification for the AI-generated, high-frequency AMV nowcasting scheme is still missing [4]. NFV ingests high-frequency 3D winds and applies continuous large-scale dynamic adjustment, likely unlocking the structural limitations of GIIRS/AMV (e.g., cloud top drift, height assignment bias), underscoring its value for numerical nowcasting.

Moreover, recent 4DVar work showed that assimilating continuous precipitation observations can constrain the large-scale field and refine mesoscale rainfall placement [68], yet NFV avoids the heavy cost of 4DVar and runs independently of 3DVar, offering an affordable option for resource-limited centers.

All schemes tested here still fail to reproduce the record-breaking 200 mm h−1 event at 09 UTC. AMV increments chiefly strengthen dynamical uplift but do not add low-level moisture (Figure 20). Recent studies stress that low-level water vapor, a key control on regional rainfall efficiency [2,69,70,71], is poorly observed from space. Future NFV development should therefore exploit high-frequency boundary-layer moisture data (FY-3D MWHS-II, ground-based GNSS-PWV, radar).

Regional operational models already update every 3 h with 3DVar on a single fine domain (e.g., 1-km CMA), matching the nudging cadence in NFV; offline 3-hourly AMV nudging can therefore be grafted onto these systems with minimal change. Yet many nudging parameters that govern FY4A 3D winds—window width, relaxation scale [44], etc. (see Table 1)—remain untuned. Sensitivity tests to fix these values are the next step toward stable geostationary-satellite assimilation in operations.

In short, NFV as the first hybrid scheme that nudges 12-km large-scale flow to force 1-km 3DVar, achieves scale-aware adjustment, and unlocks every potential of Geo-satellite AMVs assimilation. Further work should refine nudging parameters and add boundary-layer moisture observations to advance NFV nowcast skill.

7. Conclusions

This study assimilates FY4A 3D winds through the developed large-scale Nudging-forced high-resolution variational method named NFV; Nudging and Var ablation experiments quantify impacts on assimilation and nowcasting metrics. Main conclusions follow:

- Large-scale Nudging ingests observations every 3 h and persistently improves linear wind fit versus CTR; high-resolution 3DVar simultaneously improves temperature and wind fits, with both improvements concentrated at the tropopause (400~200 hPa) and Nudging ingesting more observations.

- For regional high-resolution nowcasting:

- (1)

- Upper motion: constrained by observation position accuracy, point-wise improvements from Nudging, Var, and NFV are modest; NFV and Nudging TBB evolution agree better with observations than CTR and Var, indicating notable benefit from large-scale adjustment.

- (2)

- SHR, extremes, and 6 h rainstorm: CTR and Var exhibit larger spatial heterogeneity; NFV shows the highest fractions of both categories. All experiments reproduce the observed north–south rainband, with NFV closest to observations albeit slightly northward. No experiment forecasts the 200 mm 09 UTC peak, yet Var gives the largest extreme (125 mm) and NFV the nearest location. Skill is low for short-duration heavy rain, but NFV outperforms others. Especially for 6 h rainstorm, NFV attains the highest MODE total interest (0.96) and the smallest centroid distance (36 km) among all schemes.

- (3)

- Severe convection: CTR, Var, and NFV display stratiform-dominated echoes; NFV has the highest strong-echo fraction, whereas Nudging shows weaker echoes. All three simulate cloud-street patterns close to observations with similar total interest, but NFV slightly over-forecasts. Var’s strong-echo skill is highly uncertain, while NFV is more stable and accurate, exhibiting the best spatial pattern for the main strong-echo zone.

- Spatial differences induced by different ingestion methods propagate consistently over D01 and D03: temperature discrepancies descend from model top to tropopause, RH differences descend slightly, and wind-vector differences spread both upward and downward most prominently. FY4A 3D winds at the tropopause in NFV enhance upper divergence, intensify convection over northern domains, and retard southward convection development.

Overall, NFV succeeds because its scale-aware design couples continuous, time-evolving large-scale nudging (ingesting high-frequency AMVs every 3 h) with instantaneous, fine-scale 3DVar adjustment at 1 km, a conceptual leap beyond standalone schemes. NFV highlights the benefit of scale-dependent adjustment of regional NWP using geostationary AMVs, yet involves numerous control parameters (e.g., QC thresholds and Nudging scales) and unexplored high-frequency boundary-layer moisture data (e.g., ground-based GNSS-PWV), which require further investigation to advance NFV nowcast advantages. These findings carry important scientific and practical implications for understanding regional upper systems’ modulation and enhancing local nowcasting capability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/rs18030379/s1, Figure S1: Comparison of observations (OBS) and simulations (SIM) at 09:00 UTC for OA assimilation. (a)~(c) Linear fits of FY4A OBS (x-axis) versus BAK (blue) and ANA (red) for T, U, V in observation space; RMSE, MAE, CC, and R2 are displayed. (d)~(f) Linear fits of OMA (x-axis) and OMB for T, U, V in observation space; gray diagonal indicates assimilation equivalence. (g)~(i) Vertical profiles of domain averaged AMB for T, U, V in model space; maximum absolute AMB and corresponding layer are marked. (j)~(l) AMB at model layer 32, 34, 36: temperature (shaded) and vector wind; one barb denotes 4 m s−1.; Figure S2: Same to Figure S1, but at 12:00 UTC; Figure S3: Vertical cross-sections along 113.5°E at 07:00~12:00 UTC for all experiments; x-axis denotes latitude, y-axis model level. Variables include water-vapor flux divergence (shaded, −30~30 g m2 s−1 at 10 g m−2 s−1 intervals), equivalent potential temperature (yellow contours, 300 and 360 K).; Figure S4: Same to Figure S3. Variables include vertical wind shear (shaded, −25~25 s−1 at 5 s−1 intervals), equivalent potential temperature (yellow contours, 300 and 360 K).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G. (Yakai Guo) and C.S.; methodology, Y.G. (Yakai Guo); software, A.S.; validation, Y.G. (Yakai Guo), C.S. and A.S.; formal analysis, Y.G. (Yakai Guo) and D.X.; investigation, Y.G. (Yakai Guo) and D.X.; resources, A.S. and D.X.; data curation, A.S. and Y.G. (Yanna Gao); writing—original draft preparation, Y.G. (Yakai Guo); writing—review and editing, Y.G. (Yakai Guo), C.S. and A.S.; visualization, Y.G. (Yakai Guo); project administration, C.S. and G.N.; funding acquisition, C.S. and G.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was jointly funded by the Henan Provincial Natural Science Foundation Project (grant number: 242300421367), Key Laboratory of Liuzhou Yuanbaoshan Topography Heavy Rain (grant number: 2025ybssysm2) and the Key Research and Development Projects of Henan Province (grant number: 251111322500).

Data Availability Statement

The main namelist of NFV and raw datasets used in this study can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17658802.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the CMA Henan Meteorological Bureau, the CMA Meteorological Observation Centre, the CMA National Satellite Meteorological Center, the CMA Meteorological Development and Planning Institute, the State Key Laboratory of Environment Characteristics and Effects for Near-space, and the National Supercomputing Center in Zhengzhou for their support in carrying out this study. We would like to give our many thanks to those who made efforts to advance this work, and the fellow travelers encountered along the way.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bauer, P.; Thorpe, A.; Brunet, G. The quiet revolution of numerical weather prediction. Nature 2015, 525, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, L.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, S.; Ma, S.; Zhou, K.; Shen, D.; Jiao, B.; Li, N. Observational Analysis of the Dynamic, Thermal, and Water Vapor Characteristics of the “7.20” Extreme Rainstorm Event in Henan Province, 2021. Chin. J. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 45, 1366–1383. Available online: https://www.iapjournals.ac.cn/dqkx/article/doi/10.3878/j.issn.1006-9895.2109.21160 (accessed on 5 January 2026). (In Chinese)

- Shi, W.; Li, X.; Zeng, M.; Zhang, B.; Wang, H.; Zhu, K.; Zhuge, X. Multi-model Comparison and High-Resolution Regional Model Forecast Anal-Ysis for the “7·20” Zhengzhou Severe Heavy Rain. Trans. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 44, 688–702. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zheng, J.; Min, M.; Li, B.; Xue, Y.; Ma, Y.; Lin, H.; Ren, S.; Niu, N.; Gao, L.; et al. Progress in Quantitative Applications of Fengyun Meteorological Satellite Observations in Weather Nowcasting (Invited). Acta Opt. Sin. 2024, 44, 1800002. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Gong, J.; Han, W.; Tan, W. The Evaluation of FY-4A AMVs in GRAPES RAFS. Meteorol. Mon. 2019, 45, 458–468. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Han, W.; Tian, W.; He, X. The Application of Intensive FY-2G AMVs in GRAPES_RAFS. Plateau Meteorol. 2018, 37, 1083–1093. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wan, X.; Tian, W.; Han, W.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X. The Evaluation of FY-2E Reprocessed IR AMVs in GRAPES. Meteorol. Mon. 2017, 43, 1–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Chen, K.; Xian, Z. Assessment of FY-2G Atmospheric Motion Vector Data and Assimilating Impacts on Typhoon Forecasts. Earth Space Sci. 2021, 8, e2020EA001628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormann, N.; Hernandez-Carrascal, A.; Borde, R.; Lutz, H.J.; Otkin, J.A.; Wanzong, S. Atmospheric Motion Vectors from Model Simulations. Part I: Methods and Characterization as Single-Level Estimates of Wind. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2014, 53, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, J.; Wu, D.; Daniels, J.; Friberg, M.; Bresky, W.; Madani, H. GEO–GEO Stereo-Tracking of Atmospheric Motion Vectors (AMVs) from the Geostationary Ring. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santek, D.; Dworak, R.; Nebuda, S.; Wanzong, S.; Borde, R.; Genkova, I.; García-Pereda, J.; Galante Negri, R.; Carranza, M.; Nonaka, K.; et al. 2018 Atmospheric Motion Vector (AMV) Intercomparison Study. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Lu, F.; Yang, L.; Zhang, X.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Shang, J. Image Navigation and Atmospheric Motion Vectors for FY Geosynchronous Meteorological Satellites (Invited). Acta Opt. Sin. 2024, 44, 9–23. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-Y.; Lu, Q.-F.; Wu, X.-B.; Zhang, P. Errors in height assignment for atmospheric motion vectors of FY-2C. J. Infrared Millim. Waves 2012, 31, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, S.K.; Sankhala, D.K.; Kumar, P.; Kishtawal, C.M. Retrieval and applications of atmospheric motion vectors derived from Indian geostationary satellites INSAT-3D/INSAT-3DR. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2020, 140, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shen, J.; Fan, S.; Wang, C. A study of the observational error statistics and assimilation applications of the FY-4A satellite atmospheric motion vector. Trans. Atmos. Sci. 2019, 44, 418–427. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhang, S.; Shi, J.; Liu, R. Impacts of FY-4A Atmospheric Motion Vectors on the Henan 7.20 Rainstorm Forecast in 2021. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Menzel, W.P.; Schmit, T.J.; Schmetz, J. Applications of Geostationary Hyperspectral Infrared Sounder Observations: Progress, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2022, 103, E2733–E2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaes, K.D.; Ackermann, J.; Anderson, C.; Andres, Y.; August, T.; Borde, R.; Bojkov, B.; Butenko, L.; Cacciari, A.; Coppens, D.; et al. The EUMETSAT Polar System: 13+ Successful Years of Global Observations for Operational Weather Prediction and Climate Monitoring. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2021, 102, E1224–E1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Carrascal, A.; Bormann, N. Atmospheric Motion Vectors from Model Simulations. Part II: Interpretation as Spatial and Vertical Averages of Wind and Role of Clouds. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2014, 53, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Yao, X.; Di, D.; Li, B.; Zhou, R. Three-Dimensional Wind Field Retrieval by Combining Measurements from Imager and Hyperspectral Infrared Sounder Onboard the Same Geostationary Platform. Chin. J. Atmos. Sci. 2023, 47, 1891–1906. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Santek, D.; Li, Z.; Lim, A.; Di, D.; Min, M.; Velden, C.; Menzel, W.P. Tracking Atmospheric Motions for Obtaining Wind Estimates Using Satellite Observations—From 2D to 3D. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2025, 106, E344–E363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennie, M.P.; Isaksen, L.; Weiler, F.; Kloe, J.d.; Kanitz, T.; Reitebuch, O. The impact of Aeolus wind retrievals on ECMWF global weather forecasts. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2021, 147, 3555–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe, I.; Okamoto, K. Impact of Aeolus horizontal line-of-sight wind observations on tropical cyclone forecasting in a global numerical weather prediction system. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2024, 150, 1447–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; He, J.; Ma, G.; Huang, J.; Guo, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhang, M.; Gong, J.; Zhang, P. Impact of the Detection Channels Added by Fengyun Satellite MWHS-II at 183 GHz on Global Numerical Weather Prediction. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Han, W.; Li, J.; Chen, H.; Yin, R. Impact of Assimilation of FY-4A GIIRS Three-Dimensional Horizontal Wind Observations on Typhoon Forecasts. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 42, 467–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sui, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, L.; Zhao, H.; Tang, M.; Zhan, Y.; Zhang, Z. Derivation of cloud-free-region atmospheric motion vectors from FY-2E thermal infrared imagery. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2017, 34, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, D.; Min, J.; Li, H.; Shen, F.; Lei, Y. A Machine Learning-Based Bias Correction Scheme for the All-Sky Assimilation of AGRI Infrared Radiances in a Regional OSSE Framework. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5407314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyre, J.R.; Bell, W.; Cotton, J.; English, S.J.; Forsythe, M.; Healy, S.B.; Pavelin, E.G. Assimilation of satellite data in numerical weather prediction. Part II: Recent years. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2022, 148, 521–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyre, J.R.; English, S.J.; Forsythe, M. Assimilation of satellite data in numerical weather prediction. Part I: The early years. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2019, 146, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Shen, F. All-sky infrared radiance data assimilation of FY-4A AGRI with different physical parameterizations for the prediction of an extremely heavy rainfall event. Atmos. Res. 2023, 293, 106898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhang, X.; Min, J.; Shen, F. Impacts of Assimilating All-Sky FY-4A AGRI Satellite Infrared Radiances on the Prediction of Super Typhoon In-Fa During the Period With Abnormal Changes. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2024, 129, e2024JD040784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, S.; Okamoto, K.; Okamoto, H.; Kimura, T.; Kubota, T.; Imamura, S.; Sakaizawa, D.; Fujihira, K.; Matsumoto, A.; Okabe, I.; et al. Future Space-Based Coherent Doppler Wind Lidar for Global Wind Profile Observation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, N.; Janjić, T.; Schraff, C.; Leuenberger, D.; Weissmann, M.; Reich, H.; Brousseau, P.; Montmerle, T.; Wattrelot, E.; Bučánek, A.; et al. Survey of data assimilation methods for convective-scale numerical weather prediction at operational centres. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2018, 144, 1218–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Weng, F.; Duan, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, R.; Yang, J.; Qin, X.; Han, W.; Li, J.; et al. Overview and Prospect of Data Assimilation in Numerical Weather Prediction. J. Meteorol. Res. 2025, 39, 559–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Dance, S.L.; Fowler, A.; Simonin, D.; Waller, J.; Auligne, T.; Healy, S.; Hotta, D.; Löhnert, U.; Miyoshi, T.; et al. On methods for assessment of the value of observations in convection-permitting data assimilation and numerical weather forecasting. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2025, 151, e4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Dance, S.L.; Bannister, R.N.; Chipilski, H.G.; Guillet, O.; Macpherson, B.; Weissmann, M.; Yussouf, N. Progress, challenges, and future steps in data assimilation for convection-permitting numerical weather prediction: Report on the virtual meeting held on 10 and 12 November 2021. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 2022, 24, e1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cram, J.M.; Daniels, J.; Bresky, W.; Liu, Y.; Low-Nam, S.; Sheu, R.-S. Use/Impact of NESDIS GOES Wind Data within an Operational Mesoscale RT-FDDA System. In Proceedings of the 18th Conference on Weather Analysis and Forecasting and the 14th Conference on Numerical Weather Prediction, Boulder, CO, USA, 29 July–2 August 2001; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Rabier, F. Overview of global data assimilation developments in numerical weather-prediction centres. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2006, 131, 3215–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtekamer, P.L.; Mitchell, H.L. Ensemble Kalman filtering. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2006, 131, 3269–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, A.; Shen, F.; Li, H.; Min, J.; Luo, J.; Xu, D.; Chen, J. Impacts of assimilating polarimetric radar KDP observations with an ensemble Kalman filter on analyses and predictions of a rainstorm associated with Typhoon Hato (2017). Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2025, 151, e4943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, A.; Xu, D.; Min, J.; Luo, L.; Fei, H.; Shen, F.; Guan, X.; Sun, Q. The Impacts of Assimilating Radar Reflectivity for the Analysis and Forecast of “21.7” Henan Extreme Rainstorm Within the Gridpoint Statistical Interpolation–Ensemble Kalman Filter System: Issues with Updating Model State Variables. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoke, J.; Anthes, R. The Initialization of Numerical Models by a Dynamic-Initialization Technique. Mon. Weather Rev. 1976, 104, 1551–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, T.L.; Seaman, N.L.; Stauffer, D.R. A Heuristic Study on the Importance of Anisotropic Error Distributions in Data Assimilation. Mon. Weather Rev. 2001, 129, 766–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, G.K.; Julio, T.B.; Colin, M.Z.; Vincent, E.L.; Katherine, T.C. Do Nudging Tendencies Depend on the Nudging Timescale Chosen in Atmospheric Models? J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2022, 14, e2022MS003024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, O.R., Jr.; Foroutan, H.; Gilliam, R.C.; Herwehe, J.A. Adding four-dimensional data assimilation by analysis nudging to the Model for Prediction Across Scales—Atmosphere (version 4.0). Geosci. Model Dev. 2018, 11, 2897–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seaman, N.L.; Stauffer, D.R.; Lario-Gibbs, A.M. A Multiscale Four-Dimensional Data Assimilation System Applied in the San Joaquin Valley During SARMAP. Part I: Modeling Design and Basic Performance Characteristics. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1995, 34, 1739–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Warner, T.T.; Bowers, J.F.; Carson, L.P.; Chen, F.; Clough, C.A.; Davis, C.A.; Egeland, C.H.; Halvorson, S.F.; Huck, T.W.; et al. The Operational Mesogamma-Scale Analysis and Forecast System of the U.S. Army Test and Evaluation Command. Part I: Overview of the Modeling System, the Forecast Products, and How the Products Are Used. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2008, 47, 1077–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, D.; Yin, J.; Xu, D.; Dai, G.; Chen, L. An improvement of convective precipitation nowcasting through lightning data dynamic nudging in a cloud-resolving scale forecasting system. Atmos. Res. 2020, 242, 104994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. FY-4B Atmospheric Motion Vector Product User Guide. Available online: https://img.nsmc.org.cn/PORTAL/NSMC/DATASERVICE/DataFormat/FY4A/FY-4_Product_Cloud_Motion_Vector.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2026). (In Chinese)

- Zhang, X.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Q. FY-4 Atmospheric Motion Vector Product Introduction (Tech. Rep.). Available online: https://img.nsmc.org.cn/PORTAL/NSMC/DATASERVICE/OperatingGuide/FY4B/%E9%A3%8E%E4%BA%91%E5%9B%9B%E5%8F%B7B%E6%98%9F%E4%BA%A7%E5%93%81%E4%BD%BF%E7%94%A8%E8%AF%B4%E6%98%8E%E6%96%87%E6%A1%A3_%E5%A4%A7%E6%B0%94%E8%BF%90%E5%8A%A8%E5%AF%BC%E9%A3%8E.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2026). (In Chinese)

- Li, B.; An, N.; Mou, Y. FY-4A AGRI L2 Blackbody Temperature (TBB) Data Format. Available online: https://img.nsmc.org.cn/PORTAL/NSMC/DATASERVICE/DataFormat/FY4A/Data/Format/FY-4A_AGRI_L2_TBB_NOM_4000M_V1.0.1.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2026). (In Chinese)

- Liu, Z.; Jiang, L.; Shi, C.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, Z.; Liao, J.; Yao, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, H.; et al. CRA-40/Atmosphere—The First-Generation Chinese Atmospheric Reanalysis (1979–2018): System Description and Performance Evaluation. J. Meteorol. Res. 2023, 37, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yao, S.; Jiang, L.; Liu, Z.; Shi, C.; Hu, K.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J. Collection and Pre-Processing of Satellite Remote-Sensing Data in CRA-40 (CMA’s Global Atmospheric ReAnalysis). Adv. Meteorol. Sci. Technol. 2018, 8, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kain, J.S. The Kain–Fritsch Convective Parameterization: An Update. J. Appl. Meteorol. 2004, 43, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.; Field, P.R.; Rasmussen, R.M.; Hall, W.D. Explicit Forecasts of Winter Precipitation Using an Improved Bulk Microphysics Scheme. Part II: Implementation of a New Snow Parameterization. Mon. Weather Rev. 2008, 136, 5095–5115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-Y.; Noh, Y.; Dudhia, J. A New Vertical Diffusion Package with an Explicit Treatment of Entrainment Processes. Mon. Weather Rev. 2006, 134, 2318–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacono, M.J.; Delamere, J.S.; Mlawer, E.J.; Shephard, M.W.; Clough, S.A.; Collins, W.D. Radiative Forcing by Long-lived Greenhouse Gases: Calculations with the AER Radiative Transfer Models. J. Geophys. Res. 2008, 113, D13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, P.A.; Dudhia, J.; Gonzalez-Rouco, J.F.; Navarro, J.; Montavez, J.P.; Garcia-Bustamante, E. A Revised Scheme for the WRF Surface Layer Formulation. Mon. Weather Rev. 2011, 140, 898–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, M.; Chen, F.; Wang, W.; Dudhia, J.; LeMone, M.A.; Mitchell, K.; Ek, M.; Gayno, G.; Wegiel, J.; Cuenca, R.H. Implementation and verification of the unified NOAH land surface model in the WRF model. In Proceedings of the 20th Conference on Weather Analysis and Forecasting/16th Conference on Numerical Weather Prediction, Seattle, WA, USA, 12–16 January 2004; pp. 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Kusaka, H.; Bornstein, R.; Ching, J.; Grimmond, C.S.B.; Grossman-Clarke, S.; Loridan, T.; Manning, K.W.; Martilli, A.; Miao, S.; et al. The Integrated Wrf/Urban Modelling System: Development, Evaluation, and Applications to Urban Environmental Problems. Int. J. Climatol. 2011, 31, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Hu, X.; Sun, L.; Xu, N.; Chen, L.; Zhu, A.; Lin, M.; Lu, Q.; Yang, Z.; Yang, J.; et al. The on-orbit Performance of FY-3E in an Early Morning Orbit. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2023, 105, E144–E175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, J.G.; Klemp, J.B.; Skamarock, W.C.; Davis, C.A.; Dudhia, J.; Gill, D.O.; Coen, J.L.; Gochis, D.J.; Ahmadov, R.; Peckham, S.E.; et al. The Weather Research and Forecasting Model Overview, System Efforts, and Future Directions. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2017, 98, 1717–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, R.; Hocking, J.; Turner, E.; Rayer, P.; Rundle, D.; Brunel, P.; Vidot, J.; Roquet, P.; Matricardi, M.; Geer, A.; et al. An Update on the RTTOV Fast Radiative Transfer Model (currently at Version 12). Geosci. Model Dev. 2018, 11, 2717–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roebber, P.J. Visualizing Multiple Measures of Forecast Quality. Weather Forecast. 2009, 24, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Jensen, T.; Gotway, J.H.; Bullock, R.; Gilleland, E.; Fowler, T.; Newman, K.; Blank, L.; Burek, T.; Harrold, M.; et al. The Model Evaluation Tools (MET): More Than a Decade of Community-Supported Forecast Verification. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2021, 102, E782–E807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, G.H.; Knievel, J.C.; Parker, M.D. A Multimodel Assessment of RKW Theory’s Relevance to Squall-Line Characteristics. Mon. Weather Rev. 2006, 134, 2772–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Weisman, M.L.; Rotunno, R. “A Theory for Strong Long-Lived Squall Lines” Revisited. J. Atmos. Sci. 2004, 61, 361–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Song, T.; Li, H.; Min, J.; Luo, J.; Shen, F. Four-Dimensional Variational Assimilation of Precipitation Data With the Large-Scale Analysis Constraint in the 21.7 Extreme Rainfall Event in China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2025, 130, e2024JD042522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Shu, A.; Min, J.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xu, D.; Chen, J.; Wan, S. Assimilation of Dual-Pol Radar KDP Observations With the GSI Ensemble Kalman Filter for the Analysis and Prediction of a Squall Line. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2025, 130, e2024JD041933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Song, L.; Min, J.; He, Z.; Shu, A.; Xu, D.; Chen, J. Impact of Assimilating Pseudo-Observations Derived from the “Z-RH” Relation on Analyses and Forecasts of a Strong Convection Case. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 42, 1010–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Wan, S.; Li, H.; Luo, J.; He, Z.; Fei, H.; Song, L.; Sun, Q.; Xu, D.; Chen, J. Data assimilation of weather radar reflectivity with a blending hydrometer retrieval scheme for two convective storms in East China. Atmos. Res. 2025, 321, 108110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.