MTFM: Multi-Teacher Feature Matching for Cross-Dataset and Cross-Architecture Adversarial Robustness Transfer in Remote Sensing Applications

Highlights

- Adversarial robustness can be transferred across datasets and across architectures without sacrificing clean accuracy.

- The proposed Multi-Teacher Feature Matching (MTFM) framework consistently outperforms standard models and surpasses most existing defense strategies, while requiring less training time.

- Robustness-aware knowledge transfer can serve as a scalable and efficient defense strategy in remote sensing.

- MTFM enables resilient geospatial AI systems without the computational burden of full adversarial training on every new domain.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Developed a new methodology to improve adversarial robustness in remote sensing: a feature-level multi-teacher distillation framework (MTFM) that guides the student using both clean and adversarial supervision, offering a better trade-off between clean accuracy and robustness under patch-based attacks.

- Demonstrated effective robustness transfer across datasets (e.g., EuroSAT to AID) and architectures (e.g., ResNet-152 to ResNet-50), addressing a gap in existing literature where most robustness transfer is limited to same-dataset setups.

- Compared the proposed MTFM framework with existing robustness transfer strategies, showing favorable trade-offs between clean accuracy and robustness in diverse settings.

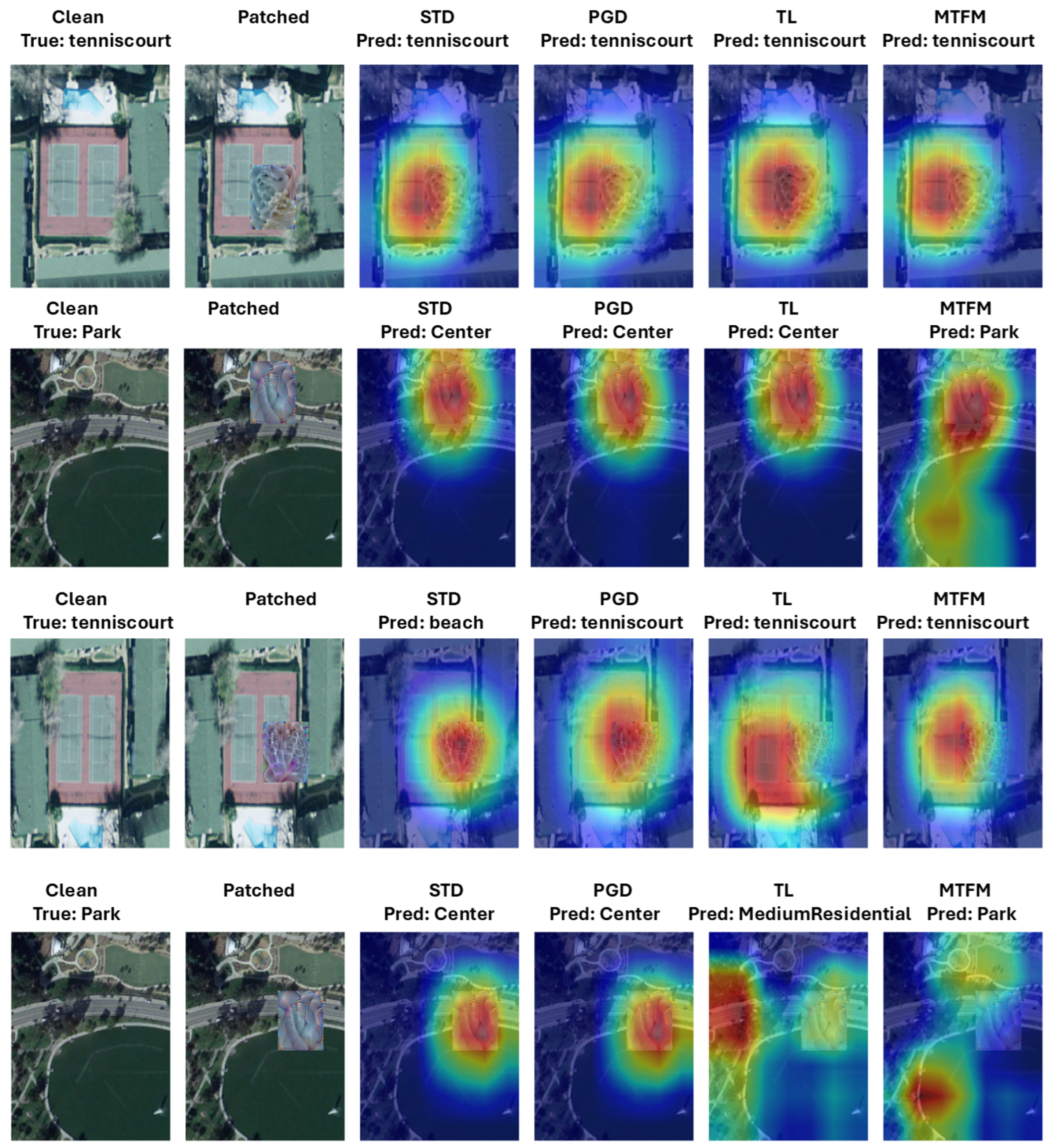

- Validated the proposed methods using adversarial test accuracy and explainable AI techniques to interpret feature alignment under patch-based attacks.

2. Related Work

2.1. Remote Sensing

2.2. Adversarial Attacks

2.3. Defense Strategy

2.4. Transferring Robustness

3. Methodology

3.1. Standard Models

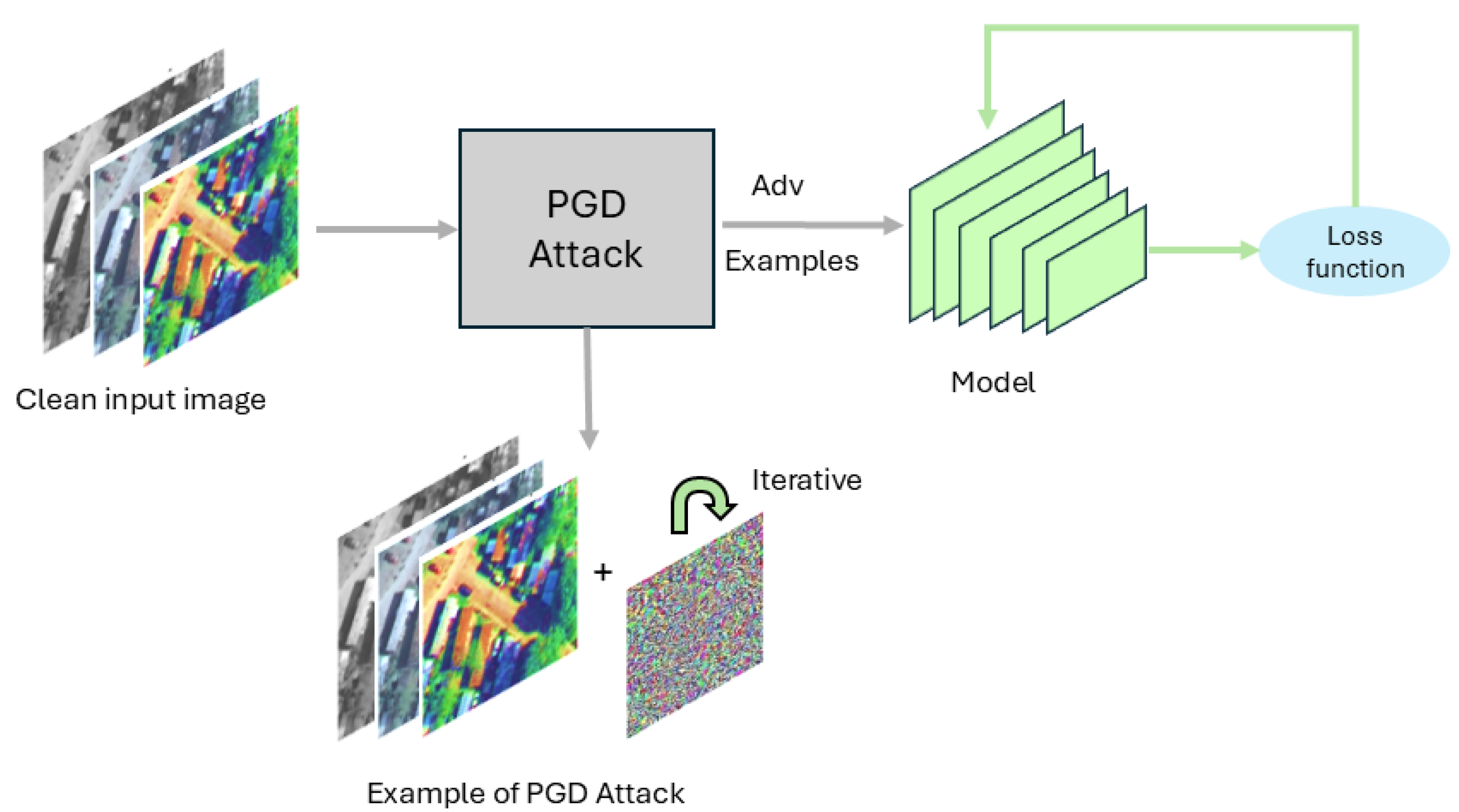

3.2. Projected Gradient Descent Adversarial Training

3.3. Self-Attention Module-Based Adversarial Robustness Transfer

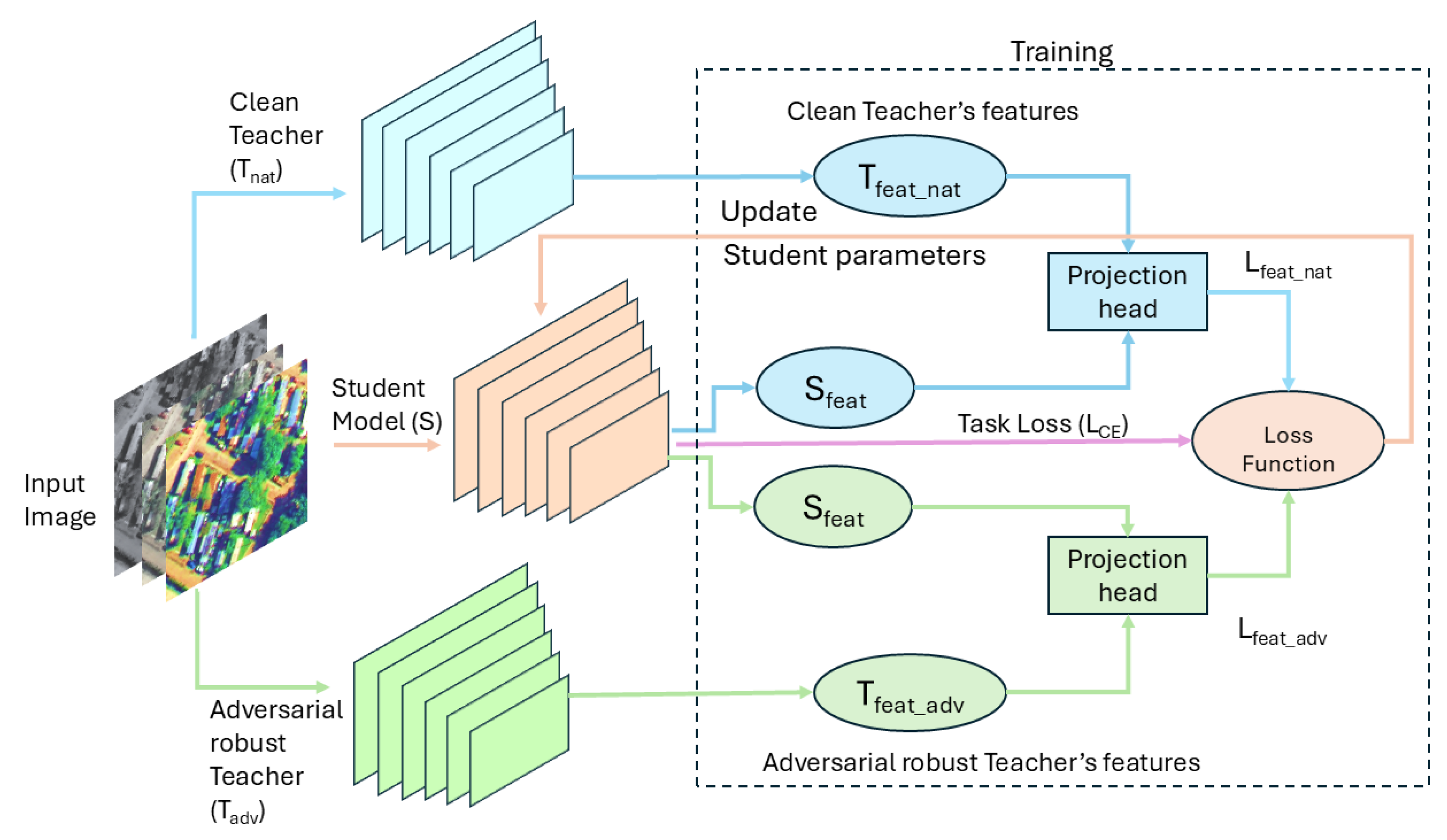

3.4. Proposed Multi-Teacher Feature Matching (MTFM) Approach

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Threat Model

4.2. Datasets

4.3. Model Architectures

4.4. Hyperparameters

4.5. Evaluation Metrics

5. Results

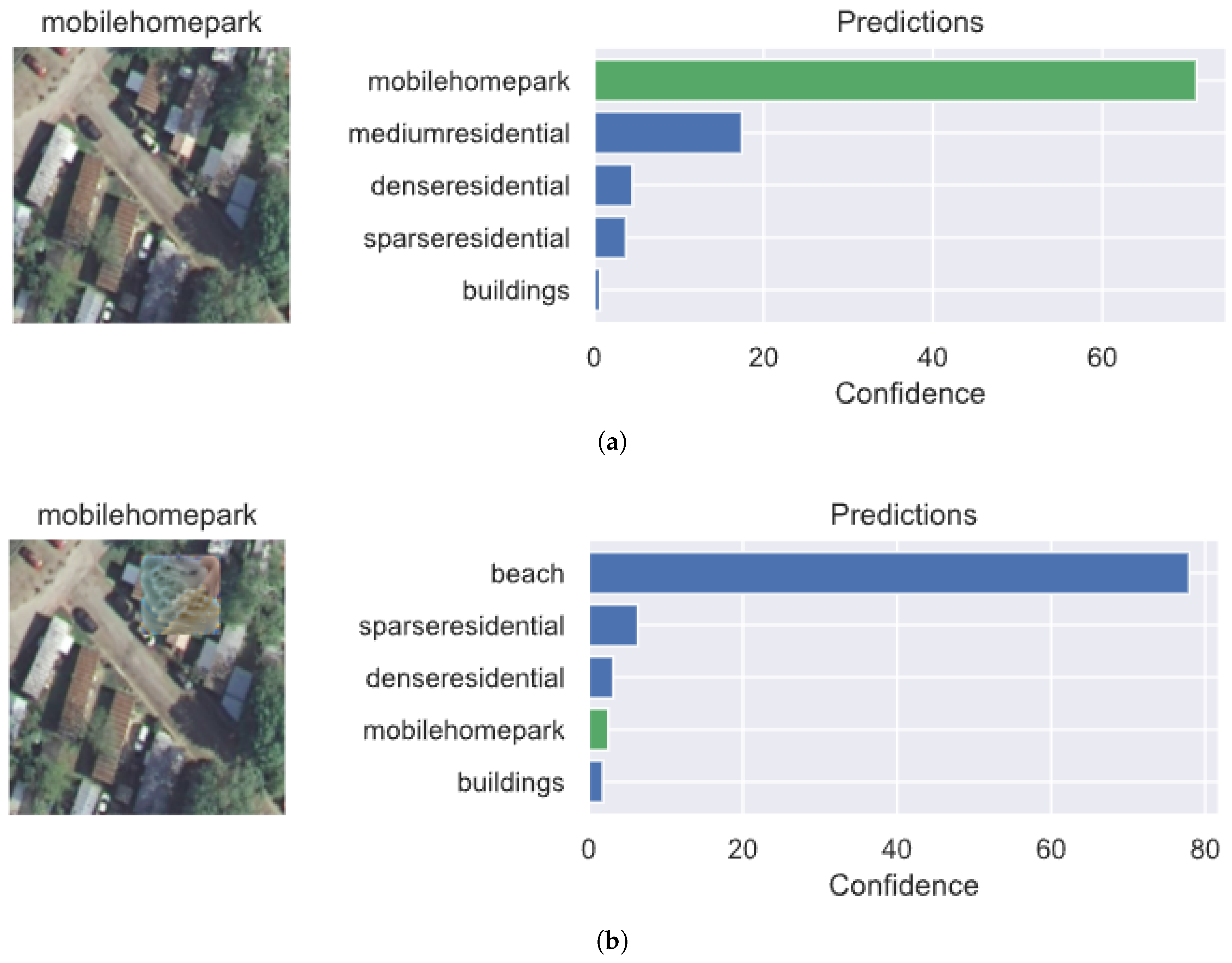

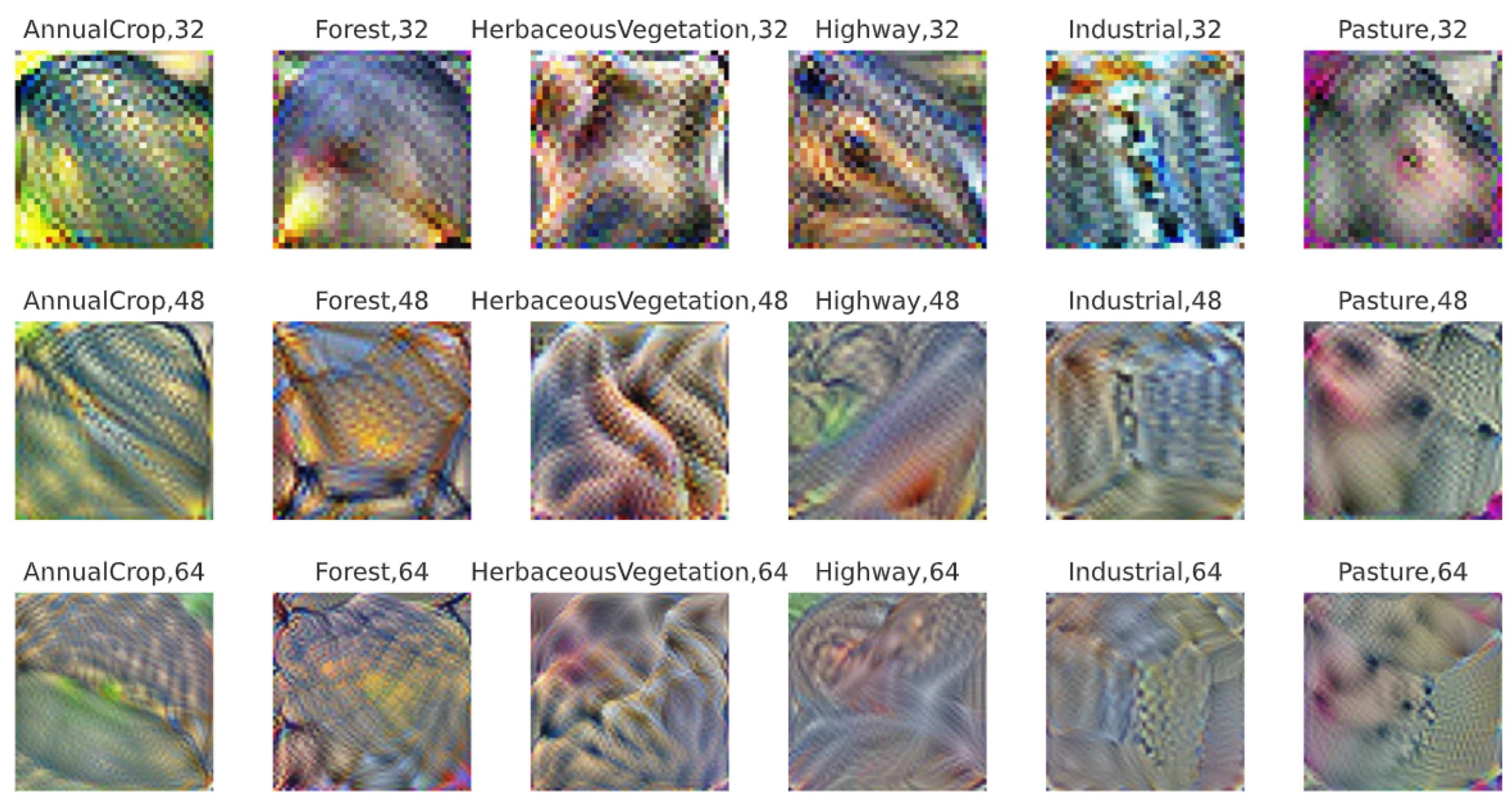

5.1. Generating Adversarial Patches

5.2. Multi Teacher Feature Matching (MTFM) Result

5.3. PatternNet → UCM and AID

5.3.1. Results on ResNet-50 (UCM and AID)

5.3.2. Results on ResNet-18 (UCM and AID)

5.4. EuroSAT → UCM and AID

5.4.1. Results on ResNet-50 (UCM and AID)

5.4.2. Results on ResNet-18 (UCM and AID)

5.5. Evaluating Performance Using Grad-CAM Visualizations

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

8. Supplementary Results

Self Attention Evaluation

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PGD-AT | Projected Gradient Descent adversarial training |

| ATA | Adversarial Test Accuracy |

| ASR | Attack Success Rate |

| Pred | Model prediction |

| Arch | Architecture |

| Standard model trained on the target dataset | |

| PGD adversarially trained model | |

| Transfer learning model with robustness transferred from a source dataset | |

| SA-TL | Self-attention-based transfer learning model |

| Multi-Teacher Adversarial Robustness Distillation | |

| Multi-Teacher Feature Matching framework |

References

- Abburu, S.; Golla, S.B. Satellite image classification methods and techniques: A review. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2015, 119, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Shen, H.; Li, T.; Li, Z.; Li, S.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, H.; Tan, W.; Yang, Q.; Wang, J.; et al. Deep learning in environmental remote sensing: Achievements and challenges. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 241, 111716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alidoost, F.; Arefi, H. Application of deep learning for emergency response and disaster management. In Proceedings of the AGSE Eighth International Summer School and Conference; University of Tehran: Tehran, Iran, 2017; pp. 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ul Hoque, M.R.; Islam, K.A.; Perez, D.; Hill, V.; Schaeffer, B.; Zimmerman, R.; Li, J. Seagrass Propeller Scar Detection using Deep Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2018 9th IEEE Annual Ubiquitous Computing, Electronics & Mobile Communication Conference (UEMCON), New York, NY, USA, 8–10 November 2018; pp. 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.B.; Mané, D.; Roy, A.; Abadi, M.; Gilmer, J. Adversarial Patch. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.09665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Yu, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, B.; Wei, X. Enhanced Accuracy and Robustness via Multi-teacher Adversarial Distillation. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022: 17th European Conference, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Proceedings, Part IV; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 585–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1512.03385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helber, P.; Bischke, B.; Dengel, A.; Borth, D. EuroSAT: A Novel Dataset and Deep Learning Benchmark for Land Use and Land Cover Classification. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1709.00029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.S.; Hu, J.; Hu, F.; Shi, B.; Bai, X.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Lu, X. AID: A Benchmark Data Set for Performance Evaluation of Aerial Scene Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 3965–3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karypidis, E.; Mouslech, S.G.; Skoulariki, K.; Gazis, A. Comparison Analysis of Traditional Machine Learning and Deep Learning Techniques for Data and Image Classification. Wseas Trans. Math. 2022, 21, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshniwal, D.; Loya, S.; Khot, A.; Marda, Y. Optimized Detection and Classification on GTRSB: Advancing Traffic Sign Recognition with Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.08283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.L.; Yuan, J.; Lunga, D.; Laverdiere, M.; Rose, A.; Bhaduri, B. Building Extraction at Scale using Convolutional Neural Network: Mapping of the United States. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1805.08946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Zaremba, W.; Sutskever, I.; Bruna, J.; Erhan, D.; Goodfellow, I.; Fergus, R. Intriguing properties of neural networks. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1312.6199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Shlens, J.; Szegedy, C. Explaining and Harnessing Adversarial Examples. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1412.6572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thys, S.; Ranst, W.V.; Goedemé, T. Fooling automated surveillance cameras: Adversarial patches to attack person detection. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.08653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Qian, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Lei, C.T.; Zhao, S.; Fang, L.; Arandjelović, O.; Lau, C.P. Beyond Vulnerabilities: A Survey of Adversarial Attacks as Both Threats and Defenses in Computer Vision Systems. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.01845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madry, A.; Makelov, A.; Schmidt, L.; Tsipras, D.; Vladu, A. Towards Deep Learning Models Resistant to Adversarial Attacks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1706.06083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, M.; Khan, S.H.; Porikli, F. Local Gradients Smoothing: Defense against localized adversarial attacks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.01216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ji, S. Generative Dynamic Patch Attack. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.04266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Xiao, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Cai, K.; Nevatia, R. PatchZero: Defending against Adversarial Patch Attacks by Detecting and Zeroing the Patch. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.01795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Tong, L.; Vorobeychik, Y. Defending Against Physically Realizable Attacks on Image Classification. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1909.09552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Chen, J.; Xue, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wan, W.; Bao, J.; Ma, H. Defending against Universal Adversarial Patches by Clipping Feature Norms. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 16414–16422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, B.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y. Defense against Adversarial Patch Attacks for Aerial Image Semantic Segmentation by Robust Feature Extraction. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2023, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Girshick, R.; Gupta, A.; He, K. Non-local Neural Networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1711.07971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, F.; Qi, Z.; Duan, K.; Xi, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Xiong, H.; He, Q. A Comprehensive Survey on Transfer Learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1911.02685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, H.; Ilyas, A.; Engstrom, L.; Kapoor, A.; Madry, A. Do Adversarially Robust ImageNet Models Transfer Better? arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.08489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, A.; Gu, J.; Xue, Z.; Carlini, N.; Wong, E.; Qin, Y. Initialization Matters for Adversarial Transfer Learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2312.05716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.02531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Li, X.; Liu, D.; Wu, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, X. Teacher-Student Architecture for Knowledge Distillation: A Survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.04268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, S.; Izmailov, P.; Kirichenko, P.; Alemi, A.A.; Wilson, A.G. Does Knowledge Distillation Really Work? arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.05945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Newsam, S. Bag-of-visual-words and spatial extensions for land-use classification. In Proceedings of the 18th SIGSPATIAL International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 2–5 November 2010; pp. 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Newsam, S.; Li, C.; Shao, Z. PatternNet: A benchmark dataset for performance evaluation of remote sensing image retrieval. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 145, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-Based Localization. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2019, 128, 336–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Model | Arch | Clean | 64 × 64 | Time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATA | ASR | secs | ||||

| PatternNet | R152 | 98.23 | 15.63 | 84.11 | 241.78 | |

| R152 | 96.57 | 83.26 | 1.5 | 2600.42 | ||

| R50 | 97.94 | 11.19 | 88.74 | 109.34 | ||

| R50 | 95.56 | 83.26 | 8.37 | 907.23 | ||

| R18 | 97.73 | 31.29 | 67.86 | 58.15 | ||

| R18 | 94.31 | 79.21 | 9.70 | 429.19 | ||

| EuroSAT | R152 | 95.12 | 5.06 | 94.43 | 171.35 | |

| R152 | 88.80 | 73.38 | 6.17 | 1880.26 | ||

| R50 | 93.53 | 2.59 | 97.4 | 90.95 | ||

| R50 | 80.86 | 60.52 | 17.31 | 777.19 | ||

| R18 | 93.78 | 1.81 | 98.14 | 65.96 | ||

| R18 | 88.0 | 78.46 | 9.31 | 390.86 | ||

| Dataset | Model | Arch | Clean | 32 × 32 | 48 × 48 | 64 × 64 | Time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATA | ASR | ATA | ASR | ATA | ASR | secs | ||||

| UCM | R50 | 88.09 | 82.0 | 3.83 | 45.0 | 47.83 | 15.83 | 82.17 | 31.82 | |

| R50 | 85.56 | 83.33 | 1.0 | 75.67 | 4.83 | 70.0 | 8.33 | 92.77 | ||

| R50->R50 | 92.85 | 89.50 | 0.17 | 85.0 | 0.17 | 82.83 | 0.33 | 32.74 | ||

| SA-TL | R50 | 91.11 | 85.83 | 0.5 | 83.33 | 1.83 | 79.5 | 8.33 | 34.99 | |

| R152->R50 | 86.82 | 82.5 | 0.17 | 81.17 | 0.01 | 77.17 | 0.05 | 109.86 | ||

| R152->R50 | 90.95 | 85.83 | 0.33 | 81.16 | 0.17 | 81.83 | 0.67 | 38.21 | ||

| AID | R50 | 91.73 | 24.78 | 74.3 | 10.44 | 84.49 | 3.97 | 96.03 | 49.83 | |

| R50 | 84.87 | 69.2 | 12.53 | 58.5 | 29.33 | 45.93 | 49.31 | 314.18 | ||

| R50->R50 | 78.07 | 73.05 | 0.89 | 72.56 | 0.82 | 69.33 | 1.68 | 39.19 | ||

| SA-TL | R50 | 77.9 | 71.90 | 1.64 | 66.36 | 1.13 | 63.52 | 2.36 | 39.86 | |

| R152->R50 | 76.43 | 71.63 | 0.68 | 67.63 | 0.51 | 67.45 | 0.93 | 368.52 | ||

| R152->R50 | 88.23 | 82.06 | 1.96 | 77.17 | 6.84 | 76.97 | 9.68 | 81.44 | ||

| UCM | R18 | 85.08 | 71.33 | 11.33 | 48.33 | 42.67 | 22.83 | 73.33 | 29.99 | |

| R18 | 79.68 | 74 | 2.0 | 71.66 | 4.66 | 63.66 | 15.33 | 64.08 | ||

| R18->R18 | 84.6 | 83.0 | 0.67 | 80.83 | 1.67 | 77.5 | 2.0 | 36.52 | ||

| SA-TL | R18 | 86.98 | 84.33 | 1.17 | 82.17 | 1.33 | 79.83 | 1.67 | 32.12 | |

| R152->R18 | 86.51 | 84.0 | 0.1 | 78.83 | 0.05 | 78.17 | 0.01 | 64.95 | ||

| R50->R18 | 84.13 | 82.83 | 0.01 | 75.67 | 0.03 | 73.5 | 0.5 | 61.99 | ||

| R152->R18 | 89.68 | 78.5 | 0.5 | 77.16 | 2.5 | 61.33 | 21.0 | 37.03 | ||

| R50->R18 | 86.99 | 76.5 | 0.5 | 71.83 | 0.16 | 71.83 | 2.83 | 33.95 | ||

| AID | R18 | 88.87 | 32.41 | 65.16 | 8.04 | 91.75 | 1.53 | 97.71 | 44.44 | |

| R18 | 83.87 | 58.93 | 1.3 | 50.41 | 10.27 | 61.34 | 8.27 | 148.11 | ||

| R18->R18 | 89.2 | 81.75 | 0.86 | 74.28 | 1.61 | 68.0 | 16.46 | 47.76 | ||

| SA-TL | R18 | 85.37 | 65.36 | 0.27 | 52.70 | 0.35 | 69.63 | 1.44 | 43.23 | |

| R152->R18 | 73.8 | 66.01 | 2.46 | 62.8 | 2.15 | 62.22 | 2.49 | 208.31 | ||

| R50->R18 | 70.17 | 66.87 | 0.27 | 63.45 | 0.58 | 61.43 | 0.31 | 170.81 | ||

| R152->R18 | 85.37 | 72.92 | 1.16 | 73.02 | 1.81 | 69.9 | 3.63 | 69.73 | ||

| R50->R18 | 88.27 | 79.22 | 1.02 | 70.39 | 1.61 | 64.50 | 7.08 | 55.38 | ||

| Dataset | Model | Arch | Clean | 32 × 32 | 48 × 48 | 64 × 64 | Time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATA | ASR | ATA | ASR | ATA | ASR | |||||

| UCM | R50 | 88.09 | 82.0 | 3.83 | 45.0 | 47.83 | 15.83 | 82.17 | 31.82 | |

| R50 | 85.56 | 83.33 | 1.0 | 75.67 | 4.83 | 70.0 | 8.33 | 92.77 | ||

| R50->R50 | 82.7 | 80.5 | 0.17 | 79.01 | 0.5 | 77.0 | 0.17 | 33.04 | ||

| SA-TL | R50 | 83.33 | 81.5 | 0.5 | 77.5 | 0.33 | 76.83 | 0.67 | 34.17 | |

| R152->R50 | 86.82 | 82.5 | 0.17 | 81.17 | 0.01 | 77.17 | 0.05 | 109.86 | ||

| R152->R50 | 90.95 | 84.33 | 1.17 | 81.83 | 0.33 | 79.0 | 0.67 | 38.02 | ||

| AID | R50 | 91.73 | 24.78 | 74.3 | 10.44 | 84.49 | 3.97 | 96.03 | 49.83 | |

| R50 | 84.87 | 69.2 | 12.53 | 58.5 | 29.33 | 45.93 | 49.31 | 314.18 | ||

| R50->R50 | 88.0 | 85.31 | 0.89 | 83.77 | 1.32 | 81.52 | 2.32 | 52.74 | ||

| SA-TL | R50 | 87.3 | 78.03 | 1.54 | 71.42 | 1.33 | 73.44 | 1.88 | 51.28 | |

| R152->R50 | 76.43 | 71.63 | 0.68 | 67.63 | 0.51 | 67.45 | 0.93 | 368.52 | ||

| R152->R50 | 90.01 | 83.81 | 0.37 | 78.44 | 0.72 | 76.66 | 2.14 | 79.04 | ||

| UCM | R18 | 85.08 | 71.33 | 11.33 | 48.33 | 42.67 | 22.83 | 73.33 | 29.99 | |

| R18 | 79.68 | 74 | 2.0 | 71.66 | 4.66 | 63.66 | 15.33 | 64.08 | ||

| R18->R18 | 79.05 | 75.33 | 1.17 | 72.33 | 0.83 | 72.17 | 1.5 | 29.09 | ||

| SA-TL | R18 | 80.32 | 76.83 | 1.5 | 72.33 | 1.5 | 71.0 | 0.83 | 32.08 | |

| R152->R18 | 86.51 | 84.0 | 0.1 | 78.83 | 0.05 | 78.17 | 0.01 | 64.96 | ||

| R50->R18 | 84.13 | 82.83 | 0.01 | 75.67 | 0.03 | 73.5 | 0.5 | 61.99 | ||

| R152->R18 | 86.83 | 78.67 | 0.67 | 76.3 | 0.87 | 70.17 | 3.16 | 30.86 | ||

| R50->R18 | 85.87 | 81.67 | 0.17 | 76.5 | 0.5 | 67.83 | 0.33 | 31.02 | ||

| AID | R18 | 88.87 | 32.41 | 65.16 | 8.04 | 91.75 | 1.53 | 97.71 | 44.44 | |

| R18 | 83.87 | 58.93 | 1.3 | 50.41 | 10.27 | 61.34 | 8.27 | 148.11 | ||

| R18->R18 | 83.23 | 76.18 | 0.82 | 68.21 | 1.16 | 75.69 | 0.92 | 47.76 | ||

| SA-TL | R18 | 82.33 | 64.22 | 0.31 | 51.81 | 0.43 | 66.39 | 0.45 | 43.23 | |

| R152->R18 | 73.8 | 66.01 | 2.46 | 62.8 | 2.15 | 62.22 | 2.49 | 208.31 | ||

| R50->R18 | 70.17 | 66.87 | 0.27 | 63.45 | 0.58 | 61.43 | 0.31 | 170.81 | ||

| R152->R18 | 84.63 | 74.19 | 0.38 | 67.72 | 0.27 | 67.63 | 2.77 | 65.25 | ||

| R50->R18 | 87.3 | 71.3 | 0.82 | 58.11 | 1.19 | 58.11 | 7.43 | 58.60 | ||

| Target | Source | Model | Arch | Clean | 32 × 32 | 48 × 48 | 64 × 64 | Time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATA | ASR | ATA | ASR | ATA | ASR | ||||||

| UCM | UCM | R50 | 89.20 | 73.33 | 13.33 | 36.0 | 60.83 | 14.17 | 85.5 | 33.73 | |

| UCM | R50 | 83.49 | 76.67 | 5.0 | 69.5 | 11.67 | 61.67 | 23.0 | 101.13 | ||

| UCM | R18 | 84.13 | 77.83 | 1.67 | 56.67 | 26.83 | 27.5 | 67.33 | 30.53 | ||

| UCM | R18 | 78.57 | 73.67 | 0.1 | 73.5 | 0.17 | 68.5 | 0.01 | 67.83 | ||

| PatterNet | R50 | 91.11 | 85.83 | 0.5 | 82.67 | 1.83 | 74.83 | 8.33 | 34.99 | ||

| PatterNet | R50 | 84.44 | 80.17 | 0.67 | 77.33 | 2.83 | 72.83 | 4.17 | 32.43 | ||

| PatterNet | R50 | 91.75 | 85.17 | 0.67 | 82.83 | 3.33 | 74.17 | 8.83 | 34.94 | ||

| PatterNet | R18 | 86.98 | 83.83 | 1.17 | 81.0 | 1.33 | 78.5 | 1.67 | 32.12 | ||

| PatterNet | R18 | 78.10 | 75.17 | 0.83 | 72.33 | 2.5 | 71.17 | 1.83 | 29.87 | ||

| PatterNet | R18 | 86.83 | 80.33 | 0.67 | 78.17 | 0.5 | 75.23 | 0.5 | 32.72 | ||

| EuroSAT | R50 | 83.33 | 82.0 | 0.5 | 77.67 | 0.33 | 76.83 | 0.67 | 34.17 | ||

| EuroSAT | R50 | 67.61 | 66.67 | 2.5 | 63.0 | 3.0 | 62.0 | 2.5 | 31.32 | ||

| EuroSAT | R50 | 82.70 | 81.0 | 0.17 | 78.0 | 0.33 | 76.17 | 0.67 | 33.27 | ||

| EuroSAT | R18 | 80.32 | 74.5 | 1.5 | 75.5 | 1.5 | 73.83 | 0.83 | 32.07 | ||

| EuroSAT | R18 | 63.97 | 61.0 | 0.83 | 61.67 | 0.67 | 59.67 | 0.17 | 30.09 | ||

| EuroSAT | R18 | 80.48 | 75.17 | 1.33 | 75.33 | 1.83 | 73.5 | 0.83 | 30.80 | ||

| AID | AID | R50 | 90.13 | 35.49 | 59.86 | 11.29 | 88.4 | 3.28 | 96.71 | 54.36 | |

| AID | R50 | 86.06 | 54.65 | 5.79 | 52.49 | 11.57 | 52.64 | 34.53 | 352.73 | ||

| AID | R18 | 89.53 | 38.26 | 52.74 | 8.49 | 91.27 | 2.46 | 97.54 | 48.99 | ||

| AID | R18 | 82.77 | 48.60 | 3.87 | 36.93 | 31.21 | 42.10 | 37.99 | 158.28 | ||

| PatterNet | R50 | 89.73 | 64.58 | 2.05 | 58.59 | 6.23 | 50.65 | 26.52 | 53.75 | ||

| PatterNet | R50 | 77.9 | 67.25 | 1.64 | 66.91 | 1.13 | 64.30 | 1.16 | 39.86 | ||

| PatterNet | R50 | 89.30 | 63.59 | 1.37 | 63.55 | 1.13 | 61.6 | 7.97 | 49.81 | ||

| PatterNet | R18 | 86.53 | 68.45 | 0.58 | 49.39 | 0.58 | 66.05 | 0.38 | 40.17 | ||

| PatterNet | R18 | 74.3 | 69.61 | 0.48 | 69.27 | 0.31 | 69.95 | 0.24 | 37.46 | ||

| PatterNet | R18 | 85.37 | 71.83 | 0.27 | 52.64 | 0.35 | 67.72 | 0.14 | 43.23 | ||

| EuroSAT | R50 | 88.33 | 69.78 | 2.40 | 65.57 | 2.81 | 64.41 | 9.21 | 54.69 | ||

| EuroSAT | R50 | 65.7 | 64.72 | 1.3 | 63.96 | 0.99 | 62.59 | 1.40 | 40.85 | ||

| EuroSAT | R50 | 87.3 | 74.97 | 1.54 | 70.74 | 1.33 | 73.54 | 1.88 | 51.28 | ||

| EuroSAT | R18 | 83.63 | 74.23 | 0.21 | 61.77 | 0.48 | 67.13 | 0.41 | 40.02 | ||

| EuroSAT | R18 | 64.87 | 62.01 | 0.58 | 62.01 | 1.13 | 62.04 | 0.82 | 36.18 | ||

| EuroSAT | R18 | 82.33 | 74.18 | 0.17 | 62.73 | 0.55 | 67.39 | 0.45 | 43.23 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rogannagari, R.K.; Islam, K.A. MTFM: Multi-Teacher Feature Matching for Cross-Dataset and Cross-Architecture Adversarial Robustness Transfer in Remote Sensing Applications. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010008

Rogannagari RK, Islam KA. MTFM: Multi-Teacher Feature Matching for Cross-Dataset and Cross-Architecture Adversarial Robustness Transfer in Remote Sensing Applications. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleRogannagari, Ravi Kumar, and Kazi Aminul Islam. 2026. "MTFM: Multi-Teacher Feature Matching for Cross-Dataset and Cross-Architecture Adversarial Robustness Transfer in Remote Sensing Applications" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010008

APA StyleRogannagari, R. K., & Islam, K. A. (2026). MTFM: Multi-Teacher Feature Matching for Cross-Dataset and Cross-Architecture Adversarial Robustness Transfer in Remote Sensing Applications. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010008