Abstract

When calculating positions, finding the optimal satellite subset is often a compromise between real-time performance and accuracy. This paper proposes a satellite selection method based on hierarchical clustering and iterative optimization. First, hierarchical clustering groups satellites on a two-dimensional projection plane are used to obtain a basic satellite subset. The relationship between GDOP and the number of satellites involved in positioning calculations is analyzed, showing that once the number of satellites reaches a certain threshold, further increases do not significantly enhance positioning accuracy. Then, the impact of a given satellite on the GDOP of the current satellite subsets is analyzed. Based on this, the most important satellite is iteratively added to the current satellite subset, gradually optimizing the spatial geometric configuration of the satellite subset. Simulations show that this method can quickly select an optimal satellite subset that meets positioning accuracy requirements under different GDOP demands, significantly improving computational efficiency compared to the traditional methods.

1. Introduction

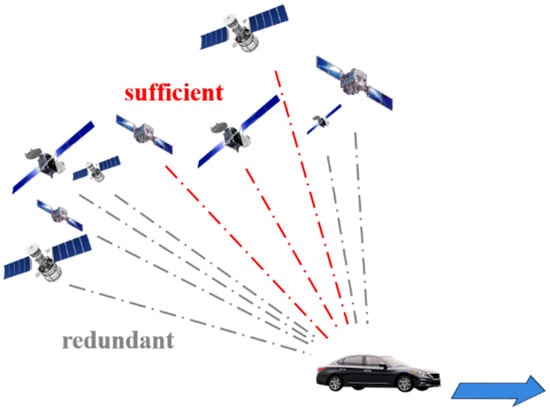

Since the BeiDou Navigation Satellite System (BDS) became fully operational in 2020, the global navigation satellite system (GNSS) has an improved overall performance and offers more reliable service for global users [1]. Since then, the number of in-orbit satellites in GNSS has increased considerably as has the amount of data GNSS produced [2]. This development is a boon for boosting the navigation and positioning accuracy of GNSS [3]. However, as more and more satellites become involved in navigation and positioning tasks, the navigation receiver must process an increasingly large amount of GNSS data. This heavy computational burden diminishes the real-time performance of navigation and positioning operations [4,5]. Moreover, once a receiver has procured sufficient GNSS data, there is not a significant improvement in the positioning accuracy, even if more satellites are involved in navigation and positioning [6]. In this case, the excess GNSS data becomes redundant while still burdening computational software. Therefore, an appropriate satellite selection strategy becomes very essential for resourcefully utilizing GNSS data as well as heightening computational efficiency in navigation and positioning, which plays a key role in areas such as autonomous driving [7] and drone navigation [8] as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Redundant satellite information during positioning or navigation.

The traditional satellite selection algorithm can determine the optimal satellite combination through calculating the Geometric Dilution of Precisions (GDOP) of all the satellite combinations [9]. The optimal satellite combination has the smallest GDOP. However, since a GDOP solution involves complex matrix multiplication and inversion operations, the computational load of calculating the GDOP for all combinations at a single epoch can skyrocket as the number of visible satellites increases, greatly reducing the efficiency of satellite selection algorithm. Refs. [10,11] have attempted to reduce the computational complexity of GDOP through the GDOP’s closed-form formulations to improve the efficiency of the satellite selection algorithm. Likewise, refs. [12,13] proposed a satellite selection algorithm in which the optimal satellite combination can be obtained through maximizing the volume of the polyhedron comprised by the unit vectors from the user to satellites. However, these satellite selection algorithms do not significantly reduce the computational costs or enhance the efficiency of satellite selection because the algorithms must still traverse all satellite combinations in the selection process.

To improve the efficiency of satellite selection, some algorithms have utilized the relationship between GDOP and the spatial geometry of the satellites for satellite selection rather than traversing all satellite combinations. By finding the convex geometric boundary containing all visible satellites, ref. [14] determined the sub-optimal satellite combination, while ref. [15] have developed a six-satellite selection algorithm by examining the impact of elevation and azimuth angles on GDOP. Ref. [16] has analyzed the optimal configuration of 4–8 satellites through exhaustive computer enumeration, and proposed a FAST algorithm, which finds the best fit of the optimal configuration according to the elevation and azimuth angles of the satellites to obtain the optimal satellite selection result. Although these satellite selection algorithms are less time-consuming than those based on the traversing strategy alone, their GDOP performance is inferior. Refs. [17,18] combined the k-means clustering with the FAST algorithm, enhancing the selection efficiency. However, since the initial cluster centers cannot be precisely determined in this way, it is hard to guarantee the effectiveness of k-means clustering, thus leading to unreliable selection results. On the other hand, satellite selection algorithms based on the contribution of each visible satellite to GDOP have been explored too. Ref. [19] employed the Sherman–Morrison formula and SVD decomposition to derive the contribution of each satellite to the GDOP of all visible satellites so that the most important satellites can be selected. Ref. [20] also calculated the GDOP contribution of each satellite and then determined the selection result by removing the satellites whose contributions are below a certain threshold value. However, the removal of low contribution value satellites can alter the spatial geometry of the satellites so that the analysis does not yield a globally optimal satellite subset. To resolve this, based on the maximum tetrahedron volume method, ref. [21] used the Sherman–Morrison formula and SVD decomposition recursively to yield increasingly optimal satellite selections. However, the traversing strategy is still required to obtain the initial subset with the maximum tetrahedron volume method, resulting in a heavy upfront computational load.

For these reasons, we have proposed a novel satellite selection method to rapidly select a relatively small optimal satellite subset for achieving real-time navigation and positioning with high precision. First, the hierarchical clustering algorithm is used to divide satellites into three groups. Then, we select one satellite from each group by maximizing the volume of the tetrahedron formed by the three satellites to be selected and the satellite with the highest elevation angle, then, we can determine the basic satellite subset. According to the impact of a given satellite on the GDOP of the basic satellite subset, the most important satellite is added to the basic satellite subset to construct a new subset. This operation is implemented iteratively to obtain the final satellite subset until the GDOP of the current subset meets positioning accuracy requirements.

2. Fast Satellite Selection Algorithm

2.1. GDOP Index for Positioning Accuracy

The GNSS positioning accuracy depends on the user equivalent range error (UERE) and the geometric distribution of navigation satellites. Positioning accuracy can be expressed as follows [22]:

where represents the standard deviation of the positioning accuracy, and represents the UERE. The GDOP is an indicator of the geometric distribution of the satellites, and thus, indicates the positioning accuracy performance. When the pseudorange measurement accuracy is fixed, the positioning accuracy is determined by GDOP. The lower the GDOP, the higher the positioning accuracy and a satellite subset with a lower GDOP has less positioning error.

When a single system is involved in positioning, the geometry matrix can be expressed as follows:

where , and represent the elevation angle and azimuth angle of the i-th satellite in the system, and the matrix is used to determine the receiver clock bias.

For multi-GNSS positioning, the time differences in multi-GNSS must be estimated. There are two ways to solve this problem. The first method is to correct the observations by using the time differences between constellations as provided in the broadcast ephemeris. The second method is to introduce an additional unknown parameter in the positioning solution to estimate the clock bias for each GNSS [23,24]. In our study, the latter is adopted. For example, for the BDS/GPS system, the geometry matrix can be expressed as follows [25]:

where and represent the number of satellites in the BDS and GPS, respectively.

Therefore, the GDOP for multi-system positioning can be written as follows:

GDOP is an important parameter for satellite selection and the evaluation of positioning accuracy [11,26,27] and has been widely used in previous studies to verify the effectiveness of satellite selection methods [2,3,17]. The relationship between GDOP and positioning accuracy is shown in Table 1 [28]. Therefore, the user’s demand for positioning accuracy can be represented by GDOP requirements.

Table 1.

Relationship between GDOP and positioning accuracy.

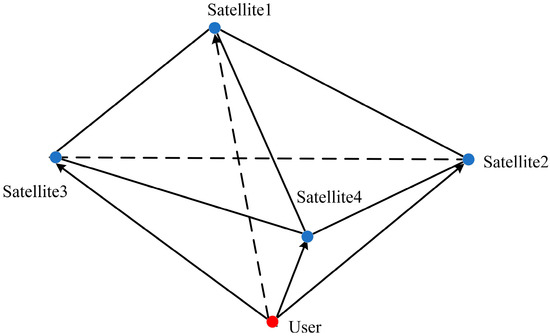

In 3-D positioning, at least four satellites are required to determine the user’s three-dimensional position and the receiver’s clock bias. When only four visible satellites are used for positioning, there is almost an inverse relationship between GDOP and the volume spanned by the user-to-satellite unit vectors [29], The space tetrahedron is shown in Figure 2. In this case, GDOP can be expressed as follows:

where represents the volume of the tetrahedron. When reaches a maximum, the GDOP is considered to have reached an optimal value.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the user-to-satellite space tetrahedron.

2.2. Proposed Satellite Selection Algorithm

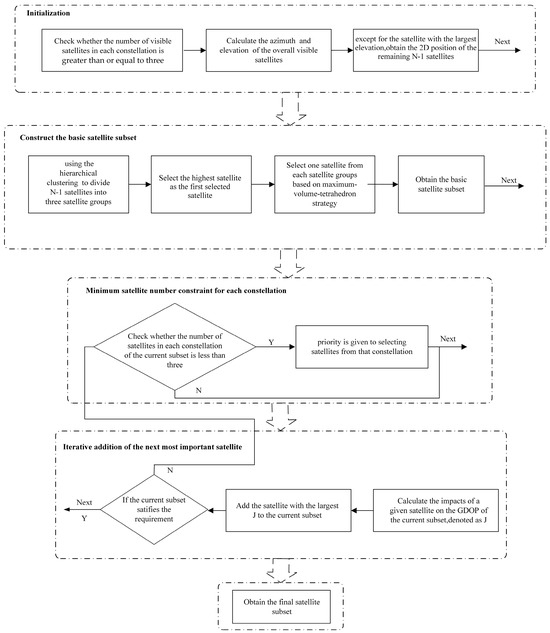

In this section, we propose a fast satellite selection algorithm based on hierarchical clustering and iterative subset optimization. First, the principles and workflow of the hierarchical clustering algorithm are reviewed. Then, we adopt the hierarchical clustering algorithm to initially divide up the satellites. Then, we determine the basic satellite subset composed of four satellites. Following that, the most significant satellite is iteratively added to the current subset to improve the GDOP performance, the schematic diagram is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic overview of the proposed fast satellite selection algorithm.

2.2.1. Initialization of Satellite Selection

Supposing that there are visible satellites at a positioning epoch, calculate the azimuth and elevation of each satellite to yield the respective sets and .

Then, except for the satellite with the largest , we obtain the 2-D position of the remaining satellites based on their azimuth and elevation, which is used for the satellites clustering, as follows:

2.2.2. Hierarchical Clustering

Hierarchical clustering is a technique for grouping data instances based on similarities, by agglomerative or divisive approach [30]. We use the more popular agglomerative hierarchical clustering to divide up the satellites [31].

Let be a data set of satellite instances, where is i-th satellite instance with m features. In this implementation, the m is defined as two, and the 2-D position in the sky view of the satellites are used to perform clustering. Each satellite is at first considered an independent cluster and cluster sets are written as follows:

where represents the j-th cluster.

Then, the two most similar clusters are merged into a new cluster. This process is repeated until a single cluster containing all the instances is yielded or until the number of the clusters reaches a predetermined threshold, which is described as follows:

where is the metric used to calculate the similarity between two clusters. It can be expressed as follows:

In Equation (11), represents the Euclidean distance between the two satellite instances . During the clustering process of satellites, the is given by:

Since hierarchical clustering is not affected by the initial cluster selection, the final clustering result is more stable and reliable than K-means clustering, in which the centroids are chosen randomly at the first step.

2.2.3. Constructing the Basic Satellite Subset

Previous studies have derived the optimal geometric configurations for satellite positioning algorithms. For instance, ref. [16] conducted computer simulations to determine the optimal configurations of satellite subsets with different sizes. Their results show that for four-satellite configurations, the optimal geometry includes one satellite located at the zenith (maximum elevation angle). Similarly, ref. [32] analyzed theoretical minimum GDOP values and proposed that for a satellite subset with four satellites, a regular tetrahedron configuration (one satellite at zenith and three others at moderate elevation angles) achieves the lowest GDOP. However, in practice, due to the atmospheric refraction of the signal, the elevation angle of the zenith satellite cannot reach 90°. Therefore, selecting the satellite with the highest elevation angle serves as the approximation to this ideal configuration. To effectively construct the basic satellite subset, we first choose the satellite with the highest elevation, denoted as .

Then, from the three satellite groups obtained through hierarchical clustering in Section 3.2, one satellite is selected, respectively, to form different satellite subsets along with the first determined satellite. The volumes of the tetrahedrons created by these subsets are calculated, and the subset that with the maximum volume is the basic satellite subset we need. This process can be expressed as:

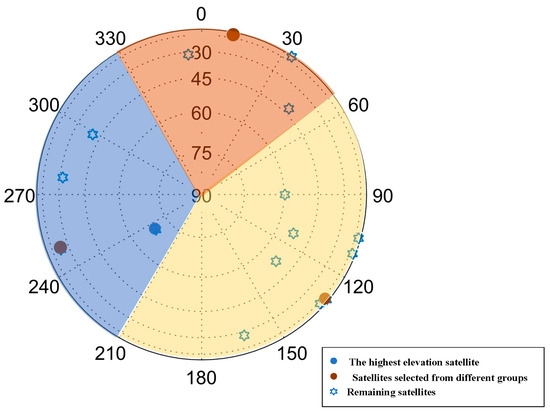

where , , represent the satellites selected from the different satellite groups and represents the basic satellite subset. An example of choosing the basic satellite subset is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

An example of selecting the basic satellite subset.

2.2.4. Iterative Addition of the Next Most Important Satellite to Improve the GDOP Performance

Once the basic satellite subset has been selected, the observation matrix of the subset is obtained, denoted as , and if a satellite with the observation vector is added to the subset, the observation matrix is changed to . The relationship between the two matrices is as follows:

where is the row vector of the added satellite.

Denoting , based on the Sherman–Morrison formula, we can obtain the following equation [33]:

Let denote the GDOP value after adding the new satellite with the observation vector and denote the GDOP value of the basic satellite subset, the relationship between and can be obtained by:

where is a scalar.

Based on Equation (17), we can obtain the impacts of the added satellite on the :

To determine the is positive or negative, making the SVD of as follows:

where is a (4 × 4) orthogonal matrix, and Z is a (4 × 4) diagonal matrix.

Substituting (20) into Equation (15), the orthogonal transformation of both sides of the equation can be obtained; then according to the Sherman–Morrison formula, we can obtain the following equation:

Since the orthogonal transformation does not change the trace of the matrix, we can obtain (22) as follows:

where , , , therefore we can obtain the following:

Equation (23) shows that the GDOP is reduced once a new satellite is added. The reduction magnitude is determined by . In other words, if the added satellite possesses the max , indicating the most significant reduction in GDOP, then it should be added to the current satellite subset to achieve better positioning accuracy. As a result, the larger the , the more important it is for positioning.

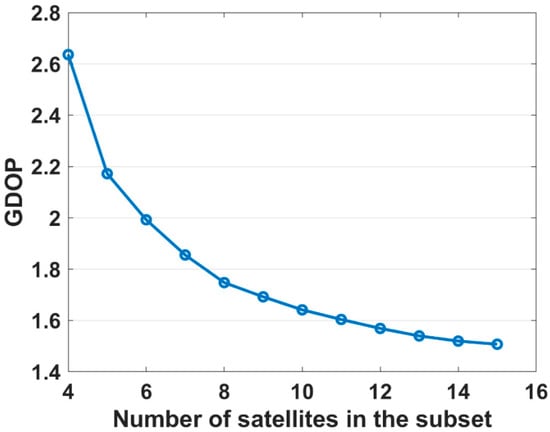

Figure 5 shows the relationship between the number of satellites selected for positioning and the subset’s GDOP value. It shows that when the number of selected satellites ranges from 4 to 8, the GDOP value decreases significantly, thus enhancing the positioning accuracy and reliability. However, when the number of satellites approaches 16, the decrease in GDOP becomes less pronounced, indicating that the positioning performance has reached a stable state. Beyond this point, adding more satellites does not significantly enhance positioning accuracy but will still increase the computational load.

Figure 5.

Relationship between the number of satellites in the subset for positioning and GDOP.

Thus, to obtain a relatively small satellite subset to satisfy positioning accuracy, we add the satellite with the largest to the current subset in each iteration, thereby maximizing the improvement of the GDOP performance of the current subset. The iteration process ends when a given subset satisfies the accuracy requirement of the positioning task, or the required number of satellites has been selected.

2.2.5. Minimum Satellite Number Constraint for Each Constellation

To ensure their accuracy and reliability, a minimum number of satellites should be set for each constellation. The suggested minimum number is three [34]. Therefore, before the initialization of satellite selection process, it is necessary to check whether the number of visible satellites in each constellation is not less than the minimum number. If a constellation has fewer than three visible satellites, satellites of the constellation will be ruled out in the subsequent satellite selection. Then, the whole satellite selection is subject to the minimum satellite number constraint. If the number of satellites in any constellation of the current satellite subset is less than three, and the number of visible satellites in the constellation is more than three, selecting priority is given to the constellation when adding the satellite with the maximum J-value to the current subset.

3. Experimental Results

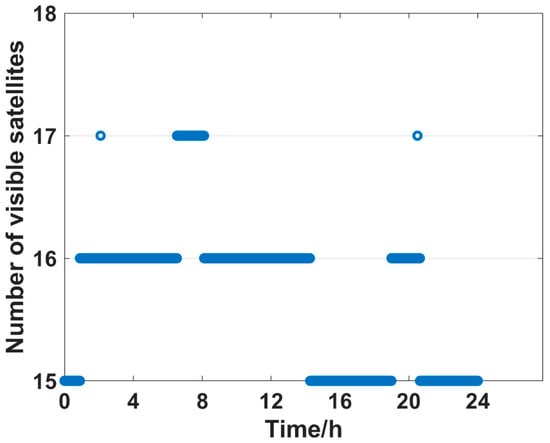

In this section, simulation experiments based on simulated data and real-world data are carried out to verify the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm and assess its performance by comparing it to other algorithms. In the simulation experiments, a 24 h satellite simulation generated the BDS data and an Intel Core i5-7400CPU @ 3.00 GHz with 16 GB RAM computer ran the simulations and calculations. The receiver was placed in Xi’an (34.158°N, 108.909°E). The satellite selection was performed every 10 s (totally 8640 epochs). The number of visible satellites ranges from 15 to 17 at each positioning epoch, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Visible satellites at different positioning epochs.

3.1. Experimental Results of Different Algorithms Based on Simulated Data

3.1.1. Experimental Result of Different Algorithms with Different Satellite Subset Sizes

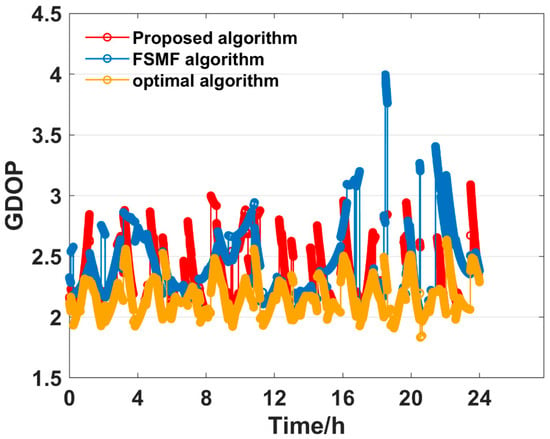

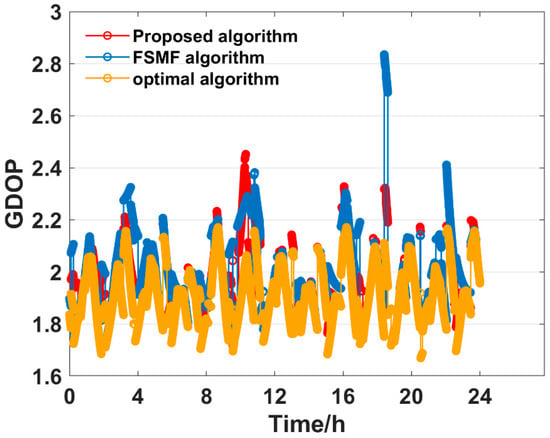

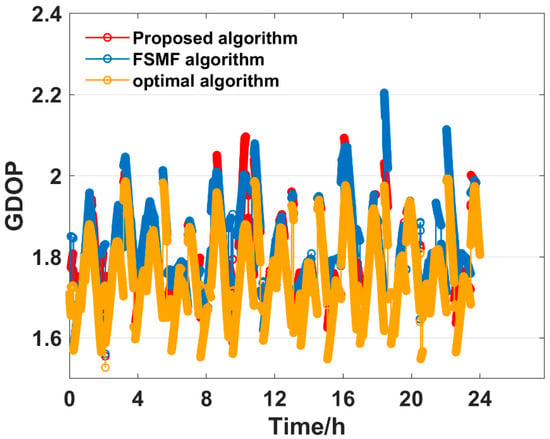

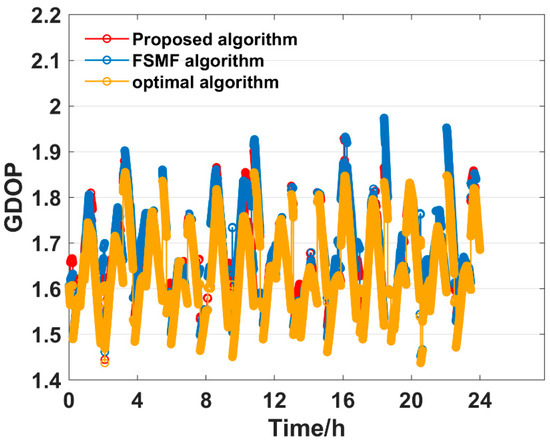

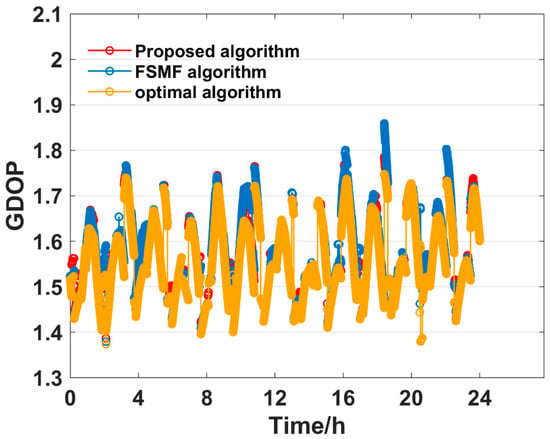

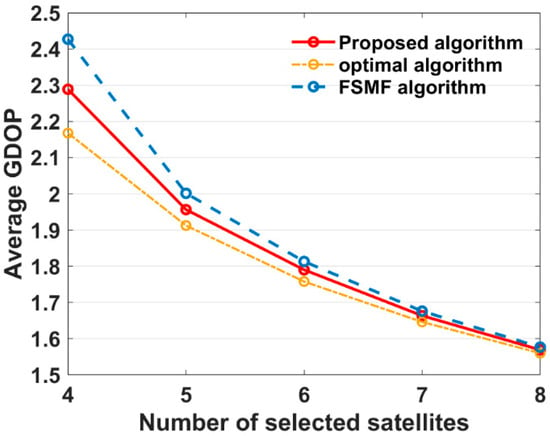

In this section, we use the proposed algorithm to make satellite selections under different satellite subset sizes. We calculate the GDOP results of the subsets when the subset size ranges from 4 to 8. Likewise, we also obtain the GDOP results at different subset sizes through the FSMF algorithm [21] and the optimal algorithm [9], respectively. The GDOP results obtained by the three algorithms at different positioning epochs are compared, as shown in Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11. The average GDOP and computation time of each algorithm are shown in Figure 12 and Figure 13.

Figure 7.

GDOP comparison when the subset size is 4.

Figure 8.

GDOP comparison when the subset size is 5.

Figure 9.

GDOP comparison when the subset size is 6.

Figure 10.

GDOP comparison when the subset size is 7.

Figure 11.

GDOP comparison when the subset size is 8.

Figure 12.

Average GDOP comparison of different algorithms with different satellite subsets.

Figure 13.

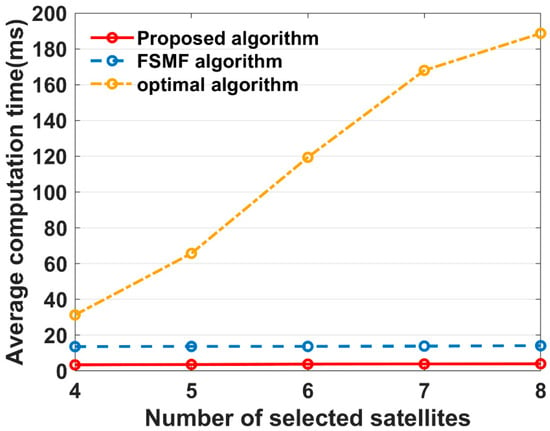

Average computation time of different algorithms with different satellite subset sizes.

In Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11, the number of selected satellites ranges from 4 to 8 and the GDOP obtained by the three algorithms generally decreases as more satellites are added, with the optimal algorithm achieving the best GDOP performance. However, as illustrated in Figure 12, with the increase in the satellite subset, the proposed algorithm’s average GDOP performance ranging from 2.288 to 1.569 is better than the FSMF algorithm’s GDOP average of 2.427 to 1.577. Notably, when the satellite subset is 4 and 5, the GDOP of the FSMF algorithm unstably fluctuates between 16:00 and 20:00 whereas the proposed algorithm does not show this instability.

Furthermore, Table 2 and Figure 13 show that as the satellite subset size increases, the computation time of the optimal algorithm increases significantly, but the proposed algorithm and the FSMF algorithm almost remain the same in the computation time. Nevertheless, the proposed algorithm outperforms the FSMF algorithm by achieving a faster computation time of less than 4 ms. The proposed method demonstrates superior performance over the FSMF algorithm in terms of both GDOP performance and computational efficiency.

Table 2.

Average computation time comparison for subset of a given size.

3.1.2. Experimental Result of Different Algorithms with Different GDOP Requirements

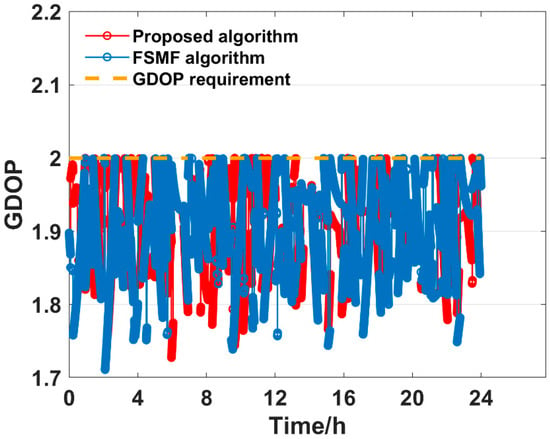

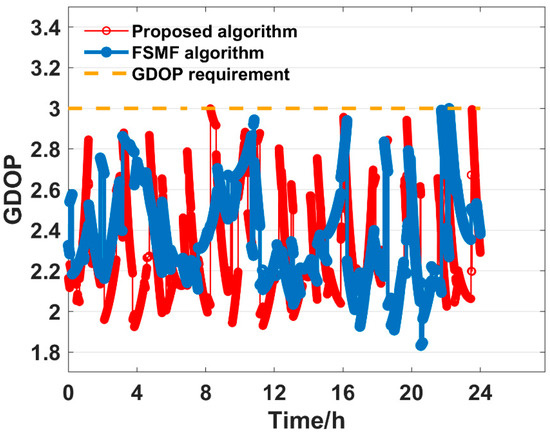

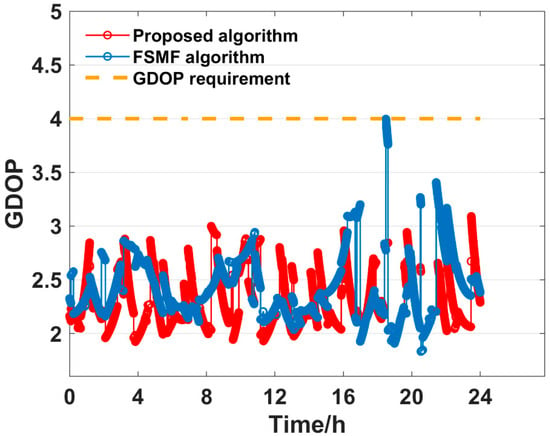

In this section, the satellite selections were carried out through the proposed algorithm with respect to three different GDOP requirements of 2, 3, 4 to evaluate the ability to obtain the minimal subset. According to these different GDOP requirements, we also use the FSMF algorithm to make the satellite selections. The computation time spent on satellite selection has also been simultaneously recorded.

The GDOP results of the subsets ultimately constructed by the two algorithms are illustrated in Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16, with the statistical summary of the GDOP provided in Table 3. The average subset size is shown in Table 4 and the average computation in Table 5.

Figure 14.

GDOP of different algorithms under = 2.0 requirement.

Figure 15.

GDOP of different algorithms under = 3.0 requirement.

Figure 16.

GDOP of different algorithms under = 4.0 requirement.

Table 3.

GDOP comparison of different algorithms ().

Table 4.

Average subset size comparison (single epoch).

Table 5.

Average computation time comparison (single epoch).

As listed in Table 4, both algorithms constructed satellite subsets with significantly fewer satellites than the total number of visible satellites to satisfy the GDOP requirements. Table 3 shows that under the GDOP requirements of 2 and 3, the two algorithms’ GDOP have similar standard deviations. However, when the GDOP requirement is increased to 4, the standard deviation of the FSMF algorithm significantly rises to 0.2986 and the FSMF algorithm requires around four satellites to meet that threshold. As analyzed in Section 3.1.1 when the satellite subset size is fixed at 4, the GDOP result of the FSMF algorithm becomes unstable, leading to a larger variance in GDOP. Moreover, Table 5 shows that the average computation time for satellite selection through the proposed algorithm remains lower than that of the FSMF algorithm. As a result, for the GDOP requirements of 2,3,4, the proposed algorithm performs well in constructing smaller and more stable satellite subsets, while also maintaining a faster computation time compared to the FSMF algorithm.

3.2. Experimental Results of Different Algorithms Based on Real-World Data

In this section, to further demonstrate the effectiveness of the algorithm, experiments were conducted using BDS/GPS satellite data collected by three different stations (ABMF, URUM and DUMG of International GNSS Service (IGS) on 1 November 2024. The receiver positions are (14.59°N, 61.00°W), (43.81°N, 87.60°E) and (66.67°S, 140.00°E), respectively. The experiments lasted for 24 h with GPS/BDS integrated system positioning every 30 s (2880 epochs). GDOP is the main indicator for evaluating positioning accuracy and can evaluate the results of algorithms. Therefore, we compared the GDOP results and computation time of the proposed method, FSMF method, and optimal method. To reduce the impact of atmospheric delays caused by low elevation angles, we set the cut-off elevation angle to 5° [35].

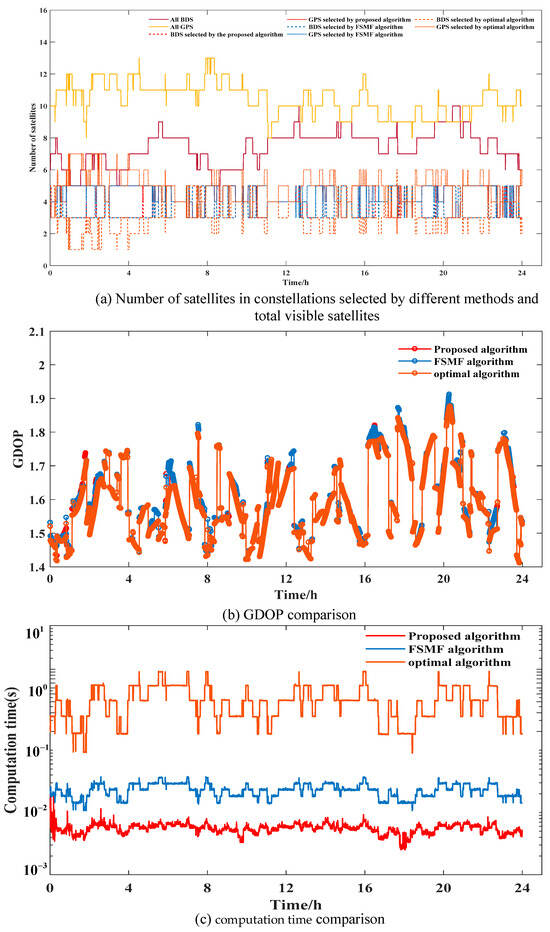

When multiple GNSSs are involved in positioning, it is necessary to ensure the required number of positioning satellites in satellite selection. Considering the detection of anomalous observation, we set the number of selected satellites to eight [3]. The computational load of satellite selection in the optimal method is extremely high, for example, selecting 8 satellites from 27 in one epoch requires GDOP calculations of . Therefore, considering the computational time cost, we compared the satellite selection results of all the three methods based on the data from the ABMF station.

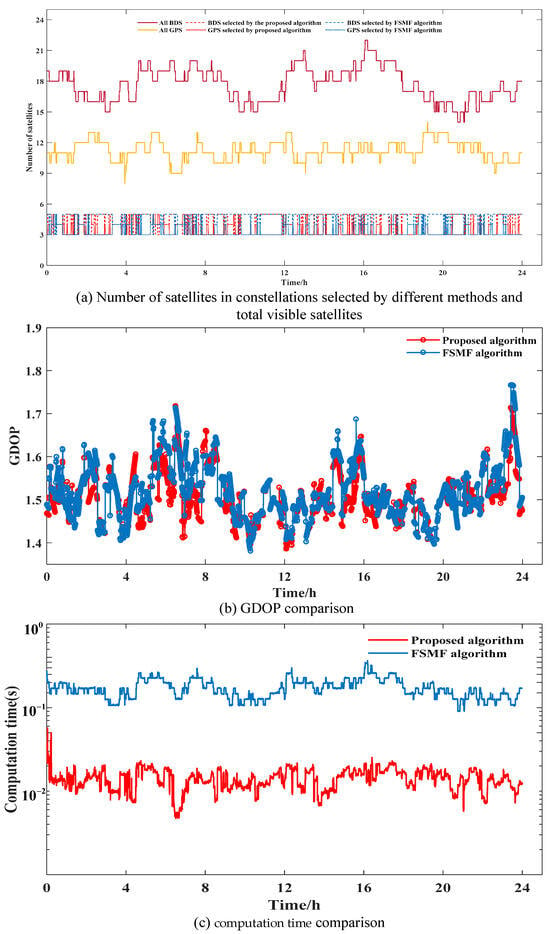

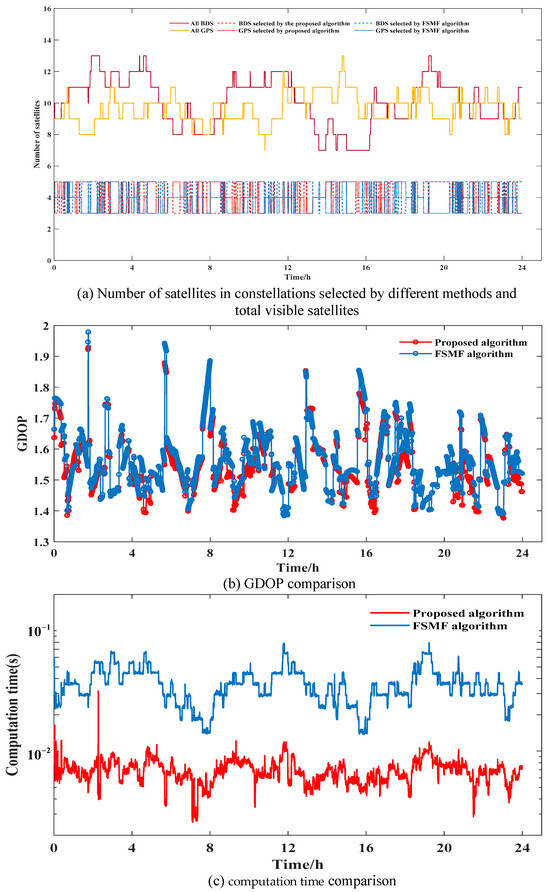

For the DUMG and URUM stations, we only compared the satellite selection results of the proposed method and the FSMF method. Figure 17a, Figure 18a, and Figure 19a present the number of BDS/GPS satellites selected by different methods, as well as the total number of GPS/BDS visible satellites for the three stations at each positioning epoch. The GDOP values of different methods are shown in Figure 17b, Figure 18b, and Figure 19b and the computation time for satellite selection is shown in Figure 17c, Figure 18c, and Figure 19c. Table 6 and Table 7 show the average GDOP values and computation time of the three methods. For the proposed method and the FSMF method, we consider the minimum satellite number constraint for each constellation, while we do not consider that for the optimal method. The average number of visible satellites for the three stations was 27, 19, and 17, respectively. From Figure 17a, Figure 18a, and Figure 19a, it can be seen that the constraint on the minimum number of satellites is satisfied in each constellation in the subsets selected by the two methods, and the number of BDS/GPS satellites selected by the two methods range from three to five, when the number of selected satellites is fixed at eight.

Figure 17.

Comparison of the number of satellites in BDS/GPS selected by different methods, GDOP values and computation time between the two algorithms at the DUMG station.

Figure 18.

Comparison of the number of satellites in BDS/GPS selected by different methods, GDOP values and computation time between the two algorithms at the URUM station.

Figure 19.

Comparison of the number of satellites in BDS/GPS selected by different methods, GDOP values and computation time for the three algorithms at the ABMF station.

Table 6.

Average GDOP values comparison when selecting eight satellites.

Table 7.

Average computation time comparison when selecting eight satellites.

Figure 17b and Figure 18b show that for the DUMG and URUM stations, there is little difference between the two methods in the GDOP values when selecting eight satellites. Table 6 shows that for the DUMG station, the average GDOP values for the proposed method and FSMF method are 1.5055 and 1.5191, respectively. For the URUM station, the average GDOP values are 1.5422 and 1.5596, with average GDOP differences of 0.0136 and 0.0174, respectively. Notably, the proposed method achieves a significant reduction in computation time when compared to the FSMF method, with reductions of approximately 91.4% and 81.0%, respectively. It can be seen that as the number of visible satellites increases, the computation time of the FSMF method grows more rapidly than that of the proposed method. This is because the FSMF method employs a global traversal strategy when selecting the initial satellite subset, resulting in a substantial increase in computation time as the number of visible satellites increases. For the ABMF station, although the GDOP performance of the optimal method is slightly better than the other methods (with GDOP differences remaining within 0.1), the computation time of the optimal method skyrockets when compared to the proposed and FSMF methods. Therefore, the proposed method demonstrates lower computational complexity while maintaining higher positioning accuracy.

4. Conclusions

We propose a fast satellite selection method based on hierarchical clustering and iterative optimization. In experiments with fixed satellite subset sizes, results show that the proposed method outperforms the FSMF algorithm in both GDOP performance and satellite selection efficiency. In experiments with different required GDOP thresholds, the proposed algorithm can construct a comparatively smaller subset of satellites to satisfy the different accuracy thresholds with more stable selection results than that of FSMF algorithm. To further validate the effectiveness of the algorithm, experiments were conducted using real-world satellite data provided by IGS from three different stations (ABMF, URUM, and DUMG). The results show that when selecting eight satellites, for the DUMG and URUM stations, the GDOP differences between the proposed method and FSMF are very small, with average differences of 0.0136 and 0.0174, respectively. Accordingly, the proposed method reduces the computation time by about 91.4% and 81.0% compared to the FSMF method. For the ABMF station, the optimal method required more computation time compared to both the proposed and FSMF methods. Therefore, the proposed algorithm can more swiftly and efficiently select an optimal satellite subset to meet positioning accuracy requirements than the other algorithms examined, reducing computational complexity and enhancing real-time performance.

Author Contributions

L.G. and D.J. provided the initial idea and designed the experiments for this study; W.L., and L.H. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; X.L., Y.Z., L.L. and M.X. helped with the result discussions and writing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Major Instrument Project of National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42127802), State Grid Hebei Power Fund project of China (Grant No. SGHEXA00SJJS2310532), the High Resolution Earth Observation Systems of National Science and Technology Major Projects (Grant No. GFZX0406120204).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Xi’an Branch of China Academy of Space Technology for collecting the data used in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| GDOP | Geometric Dilution of Precision |

| GNSS | Global navigation satellite system |

| BDS | BeiDou Navigation Satellite System |

| UERE | user equivalent range error |

| N | North |

| E | East |

References

- Gao, W.; Zhou, W.; Tang, C.; Li, X.; Yuan, Y.; Hu, X. High-precision services of BeiDou navigation satellite system (BDS): Current state, achievements, and future directions. Satell. Navig. 2024, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Y. A fast GNSS satellite selection algorithm for continuous real-time positioning. GPS Solut. 2022, 26, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, Z.; Gao, J.; Yao, Y. A fast rotating partition satellite selection algorithm based on equal distribution of sky. J. Navig. 2019, 72, 1053–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cheng, Y.; Cheng, C.; Li, S.; Li, Z. Research on satellite selection strategy for receiver autonomous integrity monitoring applications. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, C. Signal Occlusion-Resistant Satellite Selection for Global Navigation Applications Using Large-Scale LEO Constellations. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Gao, J.; Li, Z.; Li, F.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y. New Satellite Selection Approach for GPS/BDS/GLONASS Kinematic Precise Point Positioning. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Cao, Y.; Liu, J.; Benslimane, A. Localization and navigation in autonomous driving: Threats and countermeasures. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2019, 26, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrik, A.; Utama, G.; Gunawan, A.A.S.; Chowanda, A.; Suroso, J.S.; Shofiyanti, R.; Budiharto, W. GNSS-based navigation systems of autonomous drone for delivering items. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliken, R.J.; Zoller, C.J. Principle of operation of NAVSTAR and system characteristics. Navigation 1978, 25, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shing, H.D. A closed-form formula for GPS GDOP computation. GPS Solut. 2009, 13, 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, Y.; Wang, J. A closed-form formula to calculate geometric dilution of precision (GDOP) for multi-GNSS constellations. GPS Solut. 2016, 20, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihara, M.; Okada, T. A satellite selection method and accuracy for the global positioning system. Navigation 1984, 31, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Mao, X.; Li, S. BDS/GPS satellite selection algorithm based on polyhedron volumetric method. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE/SICE International Symposium on System Integration, Tokyo, Japan, 13–15 December 2014; pp. 340–345. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Delgado, N.; Nunes, F.D. Satellite selection method for multi-constellation GNSS using convex geometry. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2010, 59, 4289–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.X.; Cai, T.J. An satellites selection algorithm based on elevation and azimuth. Ship Electron. Eng. 2009, 29, 73–75. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, J. A fast satellite selection algorithm: Beyond four satellites. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2009, 3, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.K. Unsupervised learning-based satellite selection algorithm for GPS–NavIC multi-constellation receivers. GPS Solut. 2022, 26, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digumurthi, S.V.P.; Bhargav, A.H.; Babu, K.H.; Kumar, V.R. Clustering based PDOP Analysis for GPS and NavIC Combined Constellation. In Proceedings of the 2023 8th International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES), Coimbatore, India, 1–3 June 2023; pp. 1458–1463. [Google Scholar]

- Cong, L.; Abidat, A.I.; Tan, Z.Z. Analysis and simulation of the GDOP of satellite navigation. Dianzi Xuebao Acta Electron. Sin. 2006, 34, 2204–2208. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Xu, C.; Zhang, P.; Hu, C. A modified satellite selection algorithm based on satellite contribution for GDOP in GNSS. In Advances in Mechanical and Electronic Engineering: Volume 1; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 415–421. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Li, K.; Chai, L.; Liang, L.; Tian, C.; Xu, K. Fast satellite selection algorithm for GNSS multi-system based on Sherman–Morrison formula. GPS Solut. 2023, 27, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Deng, Z.; Xi, Y.; Dong, H.; Zhan, Z.; Gao, Z. A satellite selection algorithm for GNSS multi-system based on pseudorange measurement accuracy. In Proceedings of the 2013 5th IEEE International Conference on Broadband Network & Multimedia Technology, Guilin, China, 17–19 November 2013; pp. 165–168. [Google Scholar]

- Jinling, W.; Nathan, K.L.; Lu, X. Impact of the GNSS Time Offsets on Positioning Reliability. J. Glob. Position. Syst. 2011, 10, 165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, Z.Y.; Gao, Z.; Wang, S.J. A new method for satellite selection with controllable weighted PDOP threshold. Surv. Rev. 2017, 49, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Wang, J.; Huang, Q. Mathematical minimum of Geometric Dilution of Precision (GDOP) for dual-GNSS constellations. Adv. Space Res. 2016, 57, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, A.; Ou, G.; Li, G. Fast satellite selection method for multi-constellation Global Navigation Satellite System under obstacle environments. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2014, 9, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, K.; Kabir, M.H.; Kim, J.; Shin, W. GDOP-Based Low-Complexity LEO Satellite Subset Selection for Positioning. IEEE Syst. J. 2024, 18, 989–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Xie, X.; Sun, C. A fast satellite selection algorithm for positioning in LEO constellation. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 73, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Delgado, N.; Duarte Nunes, F.; Seco-Granados, G. On the relation between GDOP and the volume described by the user-to-satellite unit vectors for GNSS positioning. GPS Solut. 2017, 21, 1139–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Gao, R.; Akhavan, H. An ensemble hierarchical clustering algorithm based on merits at cluster and partition levels. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 136, 109255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, X.; Xi, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, X.; Lu, Z. Comprehensive survey on hierarcical clustering algorithms and the recent developments. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 8219–8264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Yang, Y. Positioning configurations with the lowest GDOP and their classification. J. Geod. 2015, 89, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Zhang, X.L. A fast satellite selection approach for satellite navigation system. Dianzi Xuebao Acta Electron. Sin. 2010, 38, 2887–2891. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbeth, D.; Felux, M.; Circiu, M.S.; Caamano, M. Optimized selection of satellite subsets for a multi-constellation GBAS. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Technical Meeting of The Institute of Navigation, Monterey, CA, USA, 25–28 January 2016; pp. 360–367. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, L.; Xiaohong, Z.; Fei, G. Ambiguity resolved precise point positioning with GPS and BeiDou. J. Geod. 2017, 91, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).