Enabling Value Co-Creation in the Sharing Economy: The Case of Mobike

Abstract

1. Introduction

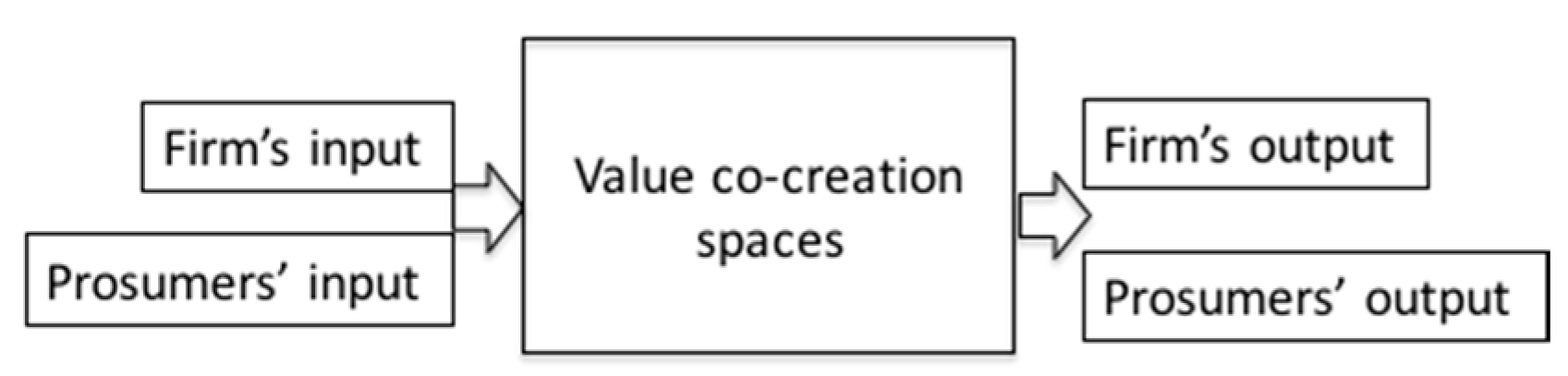

2. Prosumer, Value Co-Creation and Social Innovation in the Sharing Economy

3. Methods and Data

3.1. Case Study Context

3.1.1. The Development of FFBS

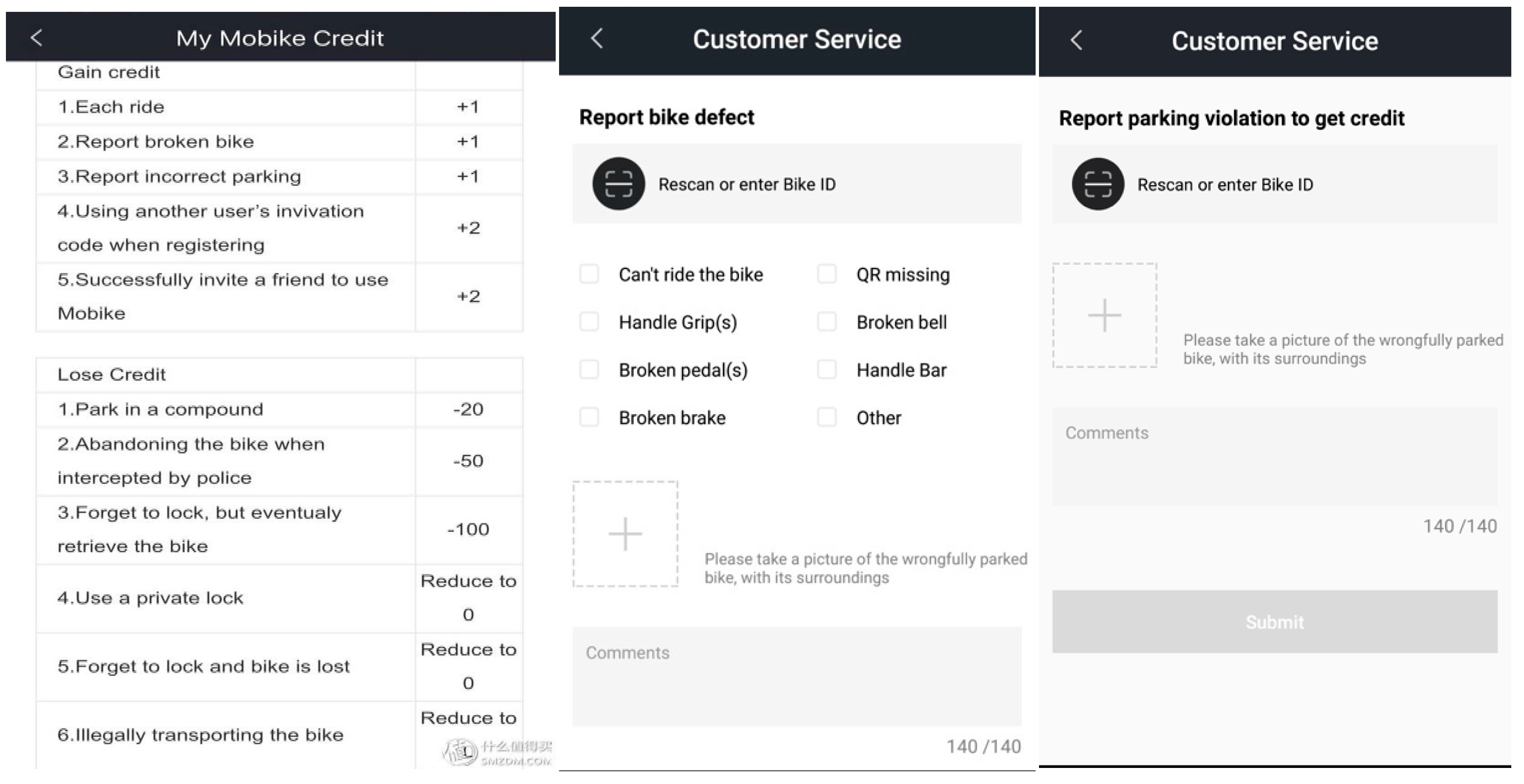

3.1.2. Mobike and Value Co-Creation Behavior

3.2. Mixed Methods

3.2.1. Stage One: Qualitative Exploration

3.2.2. Stage Two: Quantitative Factors

4. Data Analysis

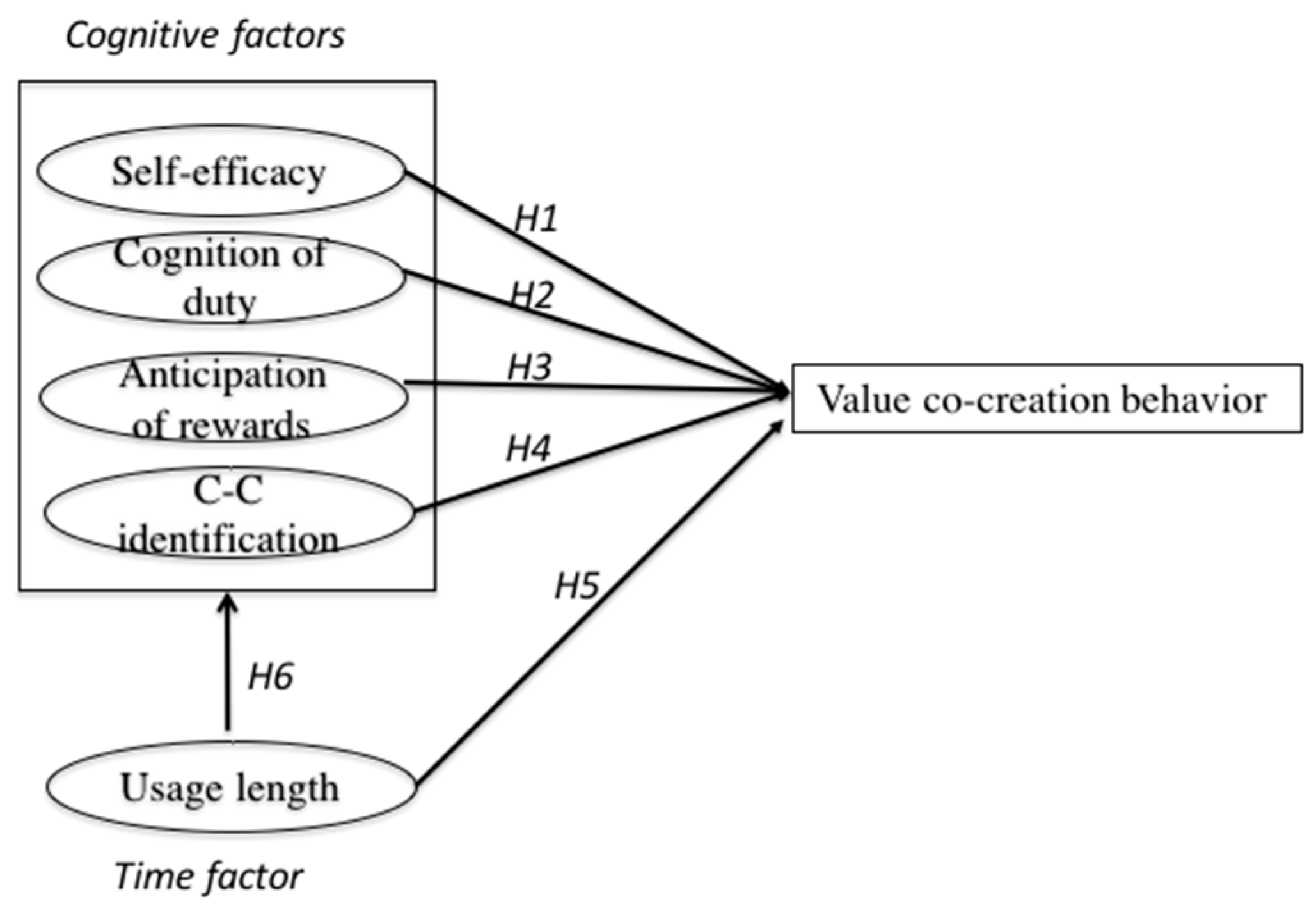

4.1. Hypotheses

4.1.1. Cognitive Factors in Value Co-Creation

“The rules are clear to me, I know what I can do and how to do it [correct use and the reporting of incorrect use].”—31 years old, female, 5 months use of Mobike

“I know the rules about how to use the bike and the whole credit score system. So I can communicate with the management team effectively [regarding reporting misbehaviors].”—34 years old, male, 4 months use of Mobike

“The principle of sharing is to consider the convenience of the next user.”—35 years old, female, 7 months use of Mobike

“It’s not only the company’s responsibility but everyone using the system [to make sure that rules are implemented].”—29 years old, male, 7 months use of Mobike

“If the system is in a bad condition, I will be affected when using the bike.”—24 years old, female, 5 months use of Mobike

“I love the bike and the service that solves our urgent ‘last mile’ transport problem, so I will help to maintain the system… The bike is stylish and high quality, and it is a green mobility, just what I want.”—19 years old, male, 5 months use of Mobike

“I like the company for its innovative ideas. Using its service can show my taste.”—26 years old, male, 6 months use of Mobike

“I’m a ‘Mobiker’. I consider myself as belonging to a group of people with similar values, who have influence on my behavior.”—34 years old, male, 4 months use of Mobike

“If I did reporting, I could get a higher score.”—24 years old, male, 4 months use of Mobike

“Though the credit prize is not high and useless by now, I feel good by getting positive response of my action… I’m proud of what I do, it’s positive energy that the other users will appreciate.”—37 years old, female, 7 months use of Mobike

“It is fun and also good for the society.”—28 years old, male, 5 months use of Mobike

“It is like a real AR [Augmented Reality] game. I enjoy it so much!”—34 years old, male, 4 months use of Mobike

4.1.2. Time as a Factor in Value Co-Creation

“It takes time and encountered experience to understand and implement the rules. [Before a mature understanding] some people are reluctant to do so.”—41 years old, male, 7 months use of Mobike

4.2. Testing the Hypothesis

4.2.1. Measures

- Section 1 selects for value co-creation participants by asking the question, “Have you participated in the reporting of bike defects and/or parking violation?” (0 = never, 1 = yes).

- Section 2 tests H1 (self-efficacy), H2 (cognition of duty), H3 (C–C identification, and H4 (anticipated rewards). All measures were adapted from literature and modified to fit the current study, that asked the respondent to react to designed statements on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree [67,69,77,78];

- Section 3 assesses H5 and H6 by asking questions about the respondent’s usage length of the Mobike service.

4.2.2. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Enabling Factors for Value Co-Creation

5.1.1. The Cognitive Factors

- Most sharing BMs are based on carefully crafted and adjustable rules, empowering frequent and timely interactions between users and the value co-creation system. The service providers normally assume that users understand the rules and follow them, even though a system of penalties is also set to remind and educate people [33]. Our data show that prosumers’ self-efficacy about the rules of the scheme varies, which has a corresponding impact on their possibility and degree of value co-creation. Firms should actively encourage and empower value co-creation by helping prosumers build self-efficacy in relation to the rules of the sharing scheme, and by making such rules and the systemic impacts of rule-oriented behavior as comprehensible as possible.

- Both the qualitative and quantitative data suggest that a milestone between passive prosumption and active value co-creation exists and correlates to the level of cognition of duty. Active prosumers consider themselves as an important component of the BM and its positive social implications, therefore invest time learning the rules quickly and join peer groups in order to be able to provide valid reporting assistance to the system. In other words, while the rules set the context, the development of duty cognition provides inner drivers to transform passive prosumers into active value co-creators.

- Anticipated rewards are necessary to sustain prosumers’ value co-creation behavior. The sense of personal responsibility within a cultural milieu may inspire people towards self-transcending actions like value co-creation, yet some expected rewards are important to incentivize prosumers to continue such behavior. As our data show, rewards can take different forms. Some are in the form of credit in the scoring system; some are in the form of enjoyment (e.g., the excitement of playing virtual reality games for some Mobike users). A engaged, nuanced and reciprocal nuanced approach is required from the firm to understand the needs of different user groups and to ensure the rewards are appropriate and lead to desirable value co-creation.

5.1.2. The Time Factor

- the latent period (below 1 month);

- the rising period (1–3 months);

- the formative period (4–6 months);

- the stable period (more than 6 months).

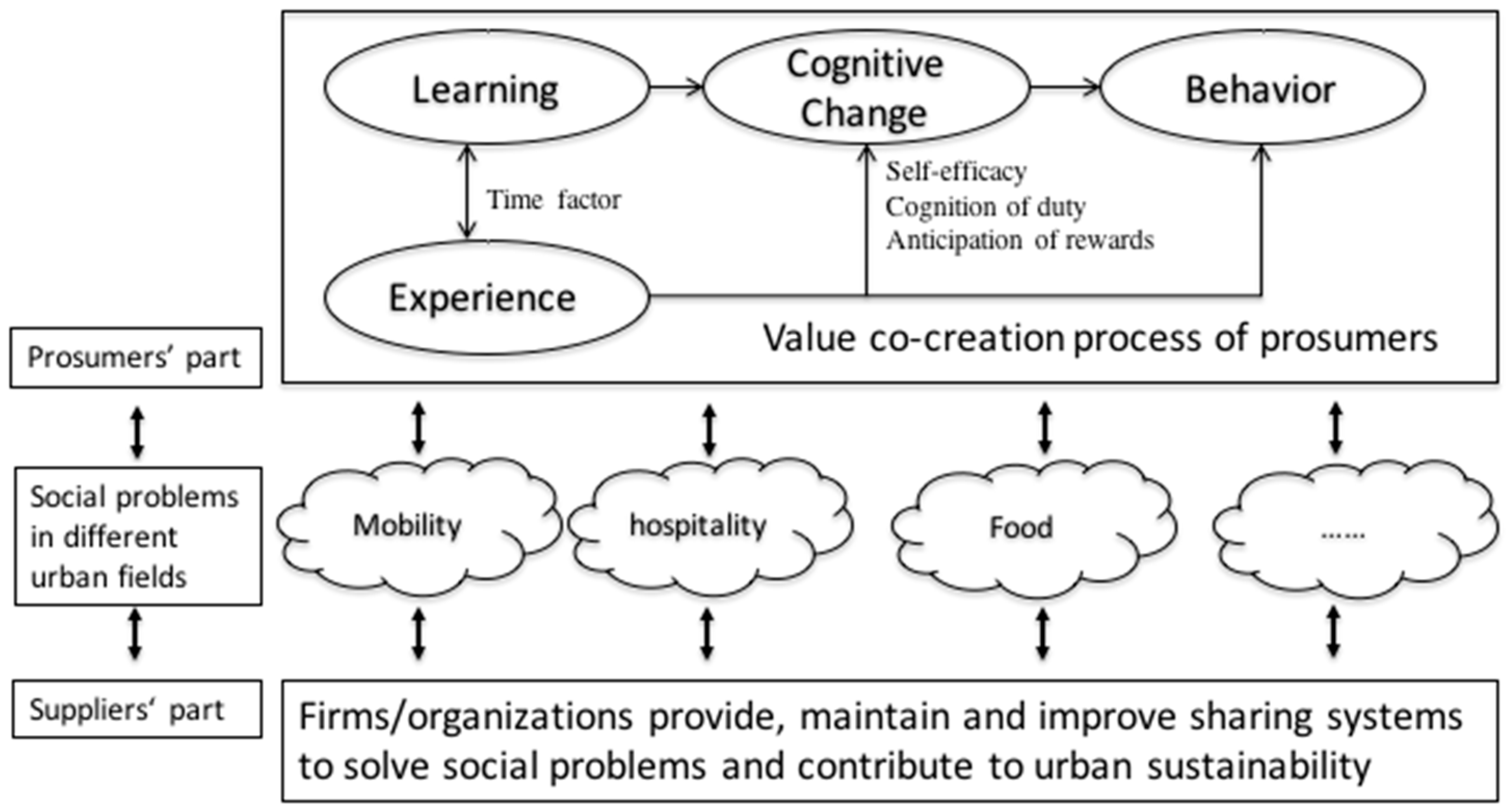

5.2. A Proposed Value Co-Creation Framework in the Sharing Economy

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Belk, R. You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lamberton, C.P.; Rose, R.L. When is ours better than mine? A framework for understanding and altering participation in commercial sharing systems. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2012, 76, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, N.A. The social logics of sharing. Commun. Rev. 2013, 16, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathan, W.; Matzler, K.; Veider, V. The sharing economy: Your business model’s friend or foe? Bus. Horiz. 2016, 59, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.D.; Kietzmann, J. Ride on! Mobility business models for the sharing economy. Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, J.; Mclaren, D. Sharing Cities: A Case for Truly Smart and Sustainable Cities; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sundararajan, A. The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefers, T.; Lawson, S.J.; Kukar-Kinney, M. How the burdens of ownership promote consumer usage of access-based services. Mark. Lett. 2016, 27, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, S.J.; Gleim, M.R.; Perren, R.; Hwang, J. Freedom from ownership: An exploration of access-based consumption. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2615–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.J.; Upham, P.; Budd, L. Commercial orientation in grassroots social innovation: Insights from the sharing economy. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 118, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.; Muñoz, P. Sharing cities and sustainable consumption and production: Towards an integrated framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayna, T. Understanding the challenges of the digital economy: The nature of digital goods. Commun. Strateg. 2010, 1, 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifkin, J. The Zero Marginal Cost Society; St. Martin’s Griffin: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Botsman, R. The Sharing Economy Lacks a Shared Definition. Available online: https://www.fastcoexist.com/3022028/the-sharing-economy-lacks-a-shared-definition (accessed on 28 February 2017).

- Ritzer, G. Prosumption: Evolution, revolution, or eternal return of the same? J. Consum. Cult. 2014, 14, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joore, P.; Han, B. A multilevel design model: The mutual relationship between product-service system development and societal change processes. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzer, G. The “new” world of prosumption: Evolution, “return of the same,” or revolution? Sociol. Forum 2015, 30, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffler, A. The Third Wave; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie, R.J.; Ilic, A.; Juric, B.; Hollebeek, L. Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzer, G.; Jurgenson, N. Production, consumption, prosumption: The nature of capitalism in the age of the digital prosumer. J. Consum. Cult. 2010, 10, 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, S. Blurring the boundaries: Prosumption, circularity and online sustainable consumption through freecycle. J. Consum. Cult. 2015, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellekom, S.; Arentsen, M.; Gorkum, K.V. Prosumption and the distribution and supply of electricity. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2016, 6, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.F.; Storbacka, K.; Frow, P. Managing the co-creation of value. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. From goods to service(s): Divergences and convergences of logics. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2008, 37, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, E.; Tronvoll, B.; Gruber, T. Expanding understanding of service exchange and value co-creation: A social construction approach. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayna, T.; Striukova, L. Involving consumers: The role of digital technologies in promoting ‘prosumption’ and user innovation. J. Knowl. Econ. 2016, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celata, F.; Hendrickson, C.Y.; Sanna, V.S. The sharing economy as community marketplace? Trust, reciprocity and belonging in peer-to-peer accommodation platforms. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2017, 10, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, R.A.; Punj, G. Repercussions of promoting an ideology of consumption: Consumer misbehavior. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 1239–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefers, T.; Wittkowski, K.; Benoit, S.; Ferraro, R. Contagious effects of customer misbehavior in access-based services. J. Serv. Res. 2015, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhi, F.; Eckhardt, G.M. Access-based consumption: The case of car sharing. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 881–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, B.; Chung, H. A framework for designing co-regulation models well-adapted to technology-facilitated sharing economies. Santa Clara High Technol. Law J. 2015, 31, 23–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hartl, B.; Hofmann, E.; Kirchler, E. Do we need rules for “what’s mine is yours”? Governance in collaborative consumption communities. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2756–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. Sharing. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 36, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertler, K.; Tasso, N. Dare to Share: User Value Co-Creation in the Sharing Economy. Master’s Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Edbring, E.G.; Lehner, M.; Mont, O. Exploring consumer attitudes to alternative models of consumption: Motivations and barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 123, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenelle, A.J. Sharing economy workers: Selling, not sharing. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2017, 10, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schor, J.B. Does the sharing economy increase inequality within the eighty percent? Findings from a qualitative study of platform providers. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2017, 10, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srnicek, N. Platform Capitalism; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Standing, G. The Corruption of Capitalism: Why Rentiers Thrive and Work Does Not Pay; Biteback Publishing: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Rong, K.; Mangalagiu, D.; Thornton, T.F.; Zhu, D. Co-evolution between urban sustainability and business ecosystem innovation: Evidence from the sharing mobility sector in Shanghai. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia Cardona, A.; Mugge, R.; Schoormans, J.P.; Schifferstein, H.N. Characteristics of Smart PSSs: Design Considerations for Value Creation. In Proceedings of the CADMC 2013: 2nd Cambridge Academic Design Management Conference, Cambridge, UK, 4–5 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five Misunderstandings about Case-Study Research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S.A.; Guzman, S.; Zhang, H. Bikesharing in Europe, the Americas, and Asia: Past, present, and future. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2010, 2143, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, E. Bikeshare: A review of recent literature. Transp. Rev. 2016, 36, 92–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungblad, S. Openbike: The design craft of future bike sharing. In Proceedings of the Crafting the Future European Academy of Design Conference, Göteborg, Sweden, 17–19 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss, S.; Paul, F.; Bogenberger, K. Empirical analysis of munich’s free-floating bike sharing system: Gps-booking data and customer survey among bikesharing users. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 11–15 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chagnon, K. America’s bike-share programs. Bicycling, 9 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gist, M.E. Self-efficacy: Implications for organizational behavior and human resource management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Measuring the involvement construct. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Conceptualizing involvement. J. Advert. 1986, 15, 4–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M.R.; Kim, A.; Laroche, M. From sharing to exchange: An extended framework of dual modes of collaborative nonownership consumption. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2016, 1, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Brodie, R.J. Wine service marketing, value co-creation and involvement: Research issues. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Harrison, S.H.; Corley, K.G. Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 325–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Bergami, M.; Marzocchi, G.L.; Morandin, G. Customer–organization relationships: Development and test of a theory of extended identities. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardador, M.T.; Pratt, M.G. Identification management and its bases: Bridging management and marketing perspectives through focus on affiliation dimensions. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindfleisch, A.; Burroughs, J.E.; Wong, N. The safety of objects: Materialism, existential insecurity, and brand connection. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 36, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einwiller, S.A.; Fedorikhin, A.; Johnson, A.R.; Kamins, M.A. Enough is enough! When identification no longer prevents negative corporate associations. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smelser, N.; Swedberg, R. Handbook of economic sociology. Eur. J. Mark. 1994, 47, 705–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, G.W.; Zmud, R.W.; Kim, Y.G.; Lee, J.N. Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological factors, and organizational climate. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlins, M. Stone Age Economics, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Habibi, M.R.; Davidson, A.; Laroche, M. What managers should know about the sharing economy. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.Z. Beyond uncertainties in the sharing economy: Opportunities for social capital. Eur. J. Risk Regul. 2016, 7, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huotari, K.; Hamari, J. Defining Gamification: A Service Marketing Perspective. In Proceedings of the International Academic Mindtrek Conference, Tampere, Finland, 3–5 October 2012; pp. 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. A diffusion of innovations. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 1963, 17, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Social learning and personality development. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1963, 23, 634–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergragt, P.J.; Brown, H.S. Sustainable mobility: From technological innovation to societal learning. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1104–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Born, A. The assessment of optimistic self-beliefs: Comparison of the Chinese, Indonesian, Japanese, and Korean versions of the general self-efficacy scale. Psychologia 1997, 40, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Meuter, M.L.; Bitner, M.J.; Ostrom, A.L.; Brown, S.W. Choosing among alternative service delivery modes: An investigation of customer trial of self-service technologies. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, P.; Mai, R.; Hoffmann, S. When do materialistic consumers join commercial sharing systems. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4215–4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, N.R. Stream renovation: An alternative to channelization. Environ. Manag. 1978, 2, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim Ghani, W.A.; Rusli, I.F.; Biak, D.R.; Idris, A. An application of the theory of planned behaviour to study the influencing factors of participation in source separation of food waste. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 1276–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stine, R.A. Graphical interpretation of variance inflation factors. Am. Stat. 1995, 49, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahearne, M.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Gruen, T. Antecedents and consequences of customer-company identification: Expanding the role of relationship marketing. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 574–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrom, E. Background on the institutional analysis and development framework. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Value Co-Creation Spaces | User Process | Reporting Process | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roles and Issues | Finding a Bike | Placing and Unlocking | Riding | Return | ||

| Service provider | Mobike Company | Mobike Company | Mobike Company | Mobike Company | User A | |

| The last user | User A | User A | Mobike Company | |||

| User A | ||||||

| Service obtainer | User A | User A | User A | The next user | Users | |

| Mobike Company | Mobike Company | |||||

| Potential issues of devaluation | Difficulties to find a bike, Defective bike | Defective App | Illegal riding | Defective App Illegal parking | User’s participation | |

| Variables | Categories | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 2 (n = 457) | ||

| Gender | Male | 52.08 |

| Female | 47.92 | |

| Age | 16–18 | 2.84 |

| 19–25 | 26.48 | |

| 26~30 | 33.26 | |

| 31~40 | 29.98 | |

| 41~50 | 4.60 | |

| 51~60 | 1.75 | |

| >60 | 1.09 | |

| Mean/SD | 29.83/4.27 | |

| Married | Yes | 43.11 |

| No | 56.89 | |

| Children | Yes | 31.95 |

| No | 68.05 | |

| Education | Up to secondary school | 3.28 |

| High school | 10.07 | |

| Bachelor’s degree or some college | 79.43 | |

| Graduate degree | 7.22 | |

| Income (yearly, CNY) | <30,000 | 14.88 |

| 30,000 to 60,000 | 21.01 | |

| 60,000 to 150,000 | 40.26 | |

| 150,000 to 250,000 | 9.19 | |

| >250,000 | 1.97 | |

| N/A | 12.69 |

| Factor Categories | Enabling Factors | Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive factors | Self-efficacy | Using the rules to remind and educate the other users |

| Providing assistance through the rules | ||

| Cognition of duty | Duty of providing convenience to the next user | |

| Duty of providing help to the system | ||

| Company–consumer identification | The bike and the FFBS service is good | |

| The company does the right thing | ||

| Belonging to a same group with other users | ||

| Anticipated rewards | Feeling good | |

| Increased credit score | ||

| Time factor | Usage length | Need time to learn and change |

| Independent Variables | Questions/Items/Scales |

|---|---|

| Predictor variables | |

| H1. Self-efficacy [ 77] | I have competence in assistance. |

| I have competence dealing with the problems. | |

| I can affect other users’ behavior. | |

| H2. Cognition of duty [78] | In my opinion, users have duty to provide assistance to the system. |

| H3. C –C identification [67] | I am somewhat associated with Mobike. |

| I have a sense of connection with Mobike. | |

| I consider myself as belonging to the group of people who are in favour of Mobike. | |

| Customers of Mobike are probably similar to me. | |

| Employees of Mobike are probably similar to me. | |

| Mobike shares my values. | |

| Being a customer of Mobike is part of my sense of who I am. | |

| Using Mobike will help me express my identity. | |

| H4. Anticipation of rewards [69] | I will receive rewards in return for my report. |

| I will receive a good feeling in return for my report. | |

| H5 and 6. Usage length | How long have you used the bike-sharing system? |

| Range from 1 = “<1 month” to 4 = “>6 months”. | |

| Control variables | |

| Gender | 0 = Female, 1 = Male. |

| Age | Range from 1 = “16–18” to 7 = “>60”. |

| Education | Range from 1 = “Up to secondary school” to 4 = “Graduate degree”. |

| Independent Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Wald | B | Wald | B | Wald | |

| H1. Self-efficacy | 0.531 ** | 5.341 | 0.555 ** | 4.601 | 0.54 ** | 4.024 |

| H2.Cognition of duty | 0.438 *** | 19.022 | 0.325 *** | 8.715 | 0.294 *** | 6.697 |

| H3.C –C Identification | 0.115 | 0.446 | 0.037 | 0.038 | −0.117 | 0.318 |

| H4. Anticipated rewards | 0.58 *** | 10.367 | 0.414 ** | 4.144 | 0.314 * | 2.832 |

| H5. Usage length | 1.095 *** | 74.75 | 1.097 *** | 69.207 | ||

| Control Variables | ||||||

| Age | −0.289 ** | 6.132 | ||||

| Gender | 0.189 | 0.592 | ||||

| Education | −0.287 | 1.483 | ||||

| Nagelkerke’s R2 | 0.184 | 0.404 | 0.448 | |||

| Independent Variables | Below 1 Month n = 106 | 1–3 Months n = 123 | 4–6 Months n = 136 | Above 6 Months n = 92 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Wald | B | Wald | B | Wald | B | Wald | |

| Self-efficacy | 0.404 | 0.393 | 0.022 | 0.002 | 0.999 * | 2.831 | 0.692 | 1.017 |

| Cognition of duty | 0.005 | 0 | 0.159 | 0.813 | 0.693 ** | 5.893 | 0.522 * | 2.755 |

| C–C Identification | −0.034 | 0.007 | −0.094 | 0.07 | −0.279 | 0.289 | 0.295 | 0.148 |

| Anticipated rewards | 0.616 | 1.252 | 0.612 * | 3.053 | −0.34 | 0.376 | 0.365 | 0.369 |

| Control Variables | ||||||||

| Age | −0.053 | 0.04 | 0.017 | 0.007 | −0.657 ** | 6.342 | −1.085 ** | 6.125 |

| Gender | 0.878 | 2.471 | 0.324 | 0.593 | −0.472 | 0.58 | 0.02 | 0.001 |

| Education | 0.347 | 0.187 | −0.954 ** | 5.678 | 0.097 | 0.031 | 0.34 | 0.3 |

| Nagelkerke’s R2 | 0.148 | 0.178 | 0.411 | 0.303 | ||||

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lan, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, D.; Mangalagiu, D.; Thornton, T.F. Enabling Value Co-Creation in the Sharing Economy: The Case of Mobike. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1504. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091504

Lan J, Ma Y, Zhu D, Mangalagiu D, Thornton TF. Enabling Value Co-Creation in the Sharing Economy: The Case of Mobike. Sustainability. 2017; 9(9):1504. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091504

Chicago/Turabian StyleLan, Jing, Yuge Ma, Dajian Zhu, Diana Mangalagiu, and Thomas F. Thornton. 2017. "Enabling Value Co-Creation in the Sharing Economy: The Case of Mobike" Sustainability 9, no. 9: 1504. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091504

APA StyleLan, J., Ma, Y., Zhu, D., Mangalagiu, D., & Thornton, T. F. (2017). Enabling Value Co-Creation in the Sharing Economy: The Case of Mobike. Sustainability, 9(9), 1504. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091504