1. Introduction

Recent years have seen several drastic climate policy shifts in a number of countries, most notably the dismantling of climate policies implemented by the Obama administration in the United States by the Trump administration. Similar drastic policy changes led by conservative governments in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom show a pattern of political volatility that is inherent to the political and institutional structure of so-called majoritarian countries, which refers to democratic systems that are characterized by a two-party minimal majority political system. This paper will aim to shed some light on the relationship between political and institutional structures and climate policy outcomes.

The transport sector accounts for about 14% of global CO2 emissions and it combines a number of other interesting factors. It is a key subject of energy security concerns, a major contributor to local air pollution, creates substantial road safety issues, and traffic congestion affects economic development negatively. Considering the role that sustainable transport polices can play in addressing these issues, it is puzzling that countries have made very differing levels of progress in this policy area. It is argued that a number of factors contribute to different policy outcomes. Differing pressures from climate change, air quality, congestion, safety, or energy security are likely to influence the time and scale of policy responses, but institutional and political structures determine the consistency and continuity of policy action. The combination of economic and environmental policy objectives makes the transport sector a particularly interesting case for an in-depth analysis of climate change policies. Transport climate change mitigation polices will be used as an example to examine, in more detail, the differences in policy making in different institutional settings.

The political environments can be very different from country to country, which affects the capacity to implement sustainable transport and other climate change mitigation measures. This study aims to explore the relevance of several political science theories to the climate and energy policy context to identify key factors that influence the policy environment in this area. There are a number of studies examining the influence of the concepts of corporatism, coordinated market economy, consensus democracy, epistemic communities, European integration, and centre-left and green party strength on environmental performance [

1,

2]. Most studies focus on higher-level environmental performance indicators and their relationship to specific institutional settings [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. This paper builds on these studies and aims to explore potential relationships between institutional frameworks and their impact on policy agenda setting and the implementation of policies and specific outcomes in the transport sector, which has often been described as one of the hardest to decarbonise [

8,

9,

10].

Some of the key institutional indicators are being explored in this paper, which will aim to shed some light on the relationship between institutional arrangements and potential influence on efforts to decarbonise the transport sector. While this will not show a linear relationship between the institutional settings and outcomes, it aims to highlight potential factors that can be considered for a governance framework that can address the complexity of a sector that requires integrated and long-term policy action at all levels of government to meet climate change targets that are in line with a stabilization well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels [

10].

2. Methodology: Factors for Continuity and Change

Social, environmental, energy, and economic drivers to implement policies that increase the efficiency of the transport sector are substantial. However, different policy environments have different effects on the implementation of certain policy measures. While some countries have strong and innovative local sustainable transport policy measures implemented, they lack progress on the national level or vice-versa [

11]. There is a large number of local and national policy measures that are ready to be implemented to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and deliver on wider sustainable development benefits [

11,

12,

13]. The reason why measures are not taken-up at their potential level relates to a number of factors, such as finance, but some are directly related to the policy environment and the institutional structure of a particular country or city. Sustainable mobility polices, such as fuel and vehicle taxation, urban planning and public transport infrastructure, are highly visible and politically sensitive issues, which require strong political support, sufficient capacity at the administrative level, consensus among key actors and stakeholders and a stable policy environment to appear on the policy agenda and to remain in place as they rely on investments that are only cost-effective over the medium to long-term [

11,

14].

A better understanding of relevant aspects related to the policy environment and institutional structures in which sustainable mobility measures are being considered, can help in the policy design and implementation. An initial analysis of several potential factors of a transport climate change policy framework will be explored in this paper, to build on aspects of policy integration, coalitions, and institutional structures that influence the policy environment.

Several potential factors will be presented in this paper to provide some indications on the policy environment as it is influenced by uncertainty, a shared set of methods and values that is vital for policy agenda setting, usually delivered through epistemic communities. This paper considers these several factors as vital contributors to enable epistemic communities to influence policy agenda setting and for policy continuity. These factors draw on political science theories focusing in particular on political consensus, corporatism, coordinated market economy, consensus democracy, and veto players. These concepts are applied to the climate change and energy policy context. Additional influencing factors are assumed to be the level of integration into the supra-national policy framework of the European Union and the strength of centre-left parties and green parties. This includes an analysis of the level of dependence of climate change mitigation policies iwith support from these parties and if and how policies evolve following changes of government. This analysis is intended to provide an input into the wider climate policy debate by aiming to highlight several governance and institutional issues and their potential to affect the climate and transport policy environment. The strategies needed to get transport onto a 1.5/2 °C stabilisation pathway require an integrated policy approach and a multilevel governance approach [

12,

15,

16,

17,

18].

3. The Relevance of Institutional Political Science Approaches

Consensual political institutions as outlined by Lijphart [

19] may lead to higher levels of policy continuity, which in turn would have positive effects for the success of climate change mitigation strategies in the transport sector. This approach also adopts the theoretical concept of “encompassing organisations” [

20] and examines the relationships between political and societal actors and their ability or inability to negotiate policies that are based on broad majorities in both politics and society. Crepaz [

21] argues that multiparty coalition governments with proportional representation and negotiation are more effective in lowering unemployment and inflation and hence creating a more favourable socio-economic environment. Lijphard and Crepaz [

19,

22] provide conceptual frameworks and supporting evidence that governments with consensual, inclusive, and accommodative constitutional structures and wider popular cabinet support act more politically responsibly than more majoritarian, exclusionary, and adversarial countries.

In countries with corporatist institutional structures, major policy issues are negotiated in a concerted effort by organised interests. Studies in this domain usually focus on the interaction between unions and employer organisations to negotiate socio-economic policies. Policy coordination among organised interests facilitates favourable policy outcomes, which relates in the case of this study to lower levels of greenhouse gas emissions in the transport sector. According to this, a high level of corporatism may influence the implementation and improvement of policies with a long-term focus. There are a number of elements which may support this, for example: comparatively encompassing interest groups, a consensual social partnership, and a broad acceptance of government regulation due to a history of strong penetration of the state in areas such as the labour market and social policy [

4]. Interest groups are integrated into the policy process in a corporatist country and broaden the basis of policies, which creates a high level of continuity that is required for long-term investments. This coalition building locks groups into certain policy directions that further enhance policy progress, which is almost self-reinforcing [

23,

24]. As a response to economic downturn, high unemployment, and inflation rates triggered by the 1970s oil price shocks, several countries with an open economy used corporatist structures to cope with increasing policy pressures [

24,

25,

26].

The concept of coordinated market economies is very similar to the general concept of corporatism, as it relies on formal institutions to regulate the market and coordinate the interaction of firms and their relations with suppliers, customers, and employees [

27]. Coordinated market economies can be characterised as having long-term relations between key actors in the economy. A particular focus in research has been the relationship between trade unions and employer associations. These long-term, cooperative relations provide coordinated market economies with a comparative advantage that positively affects the policy continuity and policy capability of a country in a similar way as corporatist structures do.

Hall and Soskice [

27] argue that the hands-off policy approach and uncoordinated interaction between policy makers, and economic and societal actors, characterises liberal market economies and puts these countries at a relative disadvantage compared to coordinated market economies. The strong interlinks between industry, banks, government, and non-governmental organisations in coordinated market economies are considered to cause inertia, but can also result in continuity and policy stability [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. The analysis of the potential relationship of carbon intensity and continuity and coherence indicators gives some indication of clusters of countries that represent certain institutional arrangements and governance structures and their transport CO

2 emissions per capita. Pluralist and less consensus oriented countries, such as the US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, have higher levels of per capita transport CO

2 emissions than nations with a strong focus on consensus building after deliberation, such as Austria, Sweden, Germany, and Switzerland. Countries such as the UK and France have both, leading to low levels of CO

2 emissions. For these countries it is argued that the membership in the European Union acts as a factor of policy stability [

32,

33]. In addition, cohabitation (France) and the strength of the Labour Party (UK) when it was in power, are considered to have contributed to emission reductions in these two countries in the early 2000s [

34]. A follow-up analysis assessing changes after the United Kingdom will have left the EU, may further provide indications of the role of the EU in policy stability, following the UK´s decision to leave the European Union. The divide between various countries becomes even more obvious when comparing the level of consensus in various EU and non-EU member countries regarding increasing or decreasing emissions reductions in the respective transport sectors, which reflects the actual progress in low-carbon transport policy (or the lack thereof). This is becoming particularly obvious when comparing climate policy approaches in the EU and the US, which will be outlined in

Section 5 after some of the factors outlined in this section have been analysed in a set of multivariate-variate correlations.

4. Institutional Factors and Their Relationship to Policy Outputs and Outcomes

4.1. Epistemic Communities, Societal Consensus, and the Uncertainties of Climate Change Impacts

While the basic physics of anthropogenic climate change are scientifically robust, there remains uncertainty over the scale and timing of climate change impacts, which makes policy making much more complicated than in other areas [

12]. The adoption of a precautionary approach is therefore vital and the “lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation” [

35]. The debate has moved in many countries from climate science to climate action. Since the First Assessment Report was published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 1990, some countries have steadily progressed climate change mitigation policies, while others have experienced substantial political volatility in this area. Uncertainty about the potential impacts of climate change makes decision-making very difficult and complex. A critical factor from the policy makers’ perspective is the impact chain, characterised by increasing scientific uncertainty, which is related to the complex nature of the global climate system [

8]. While the scientific understanding of the impact pathway has improved, climate change policies are often stalled by uncertainty about risks [

36]. Issues such as climate change require particular sorts of information, which are not based on ideology, guesswork, or raw scientific data, but are a human interpretation of social and physical phenomena [

37,

38]. It is argued that epistemic communities are vital in providing this information to enable policy action and consensus building. The members of an epistemic community share the same values and understanding of causal relationships, which creates the foundation for policy decisions in consensus or compromise [

24,

39,

40]. An epistemic community can produce consensual knowledge, even if the level of scientific evidence is uncertain or inconclusive [

38,

41].

Epistemic communities are a “network of professionals with recognized expertise and competence in a particular domain and an authoritative claim to policy-relevant knowledge within that domain or issue-area” [

38]. Regardless of the professional background, epistemic communities have a shared set of normative and principled beliefs, which provide a value-based rationale for the social action of community members. They share causal beliefs, which serve as the basis for identifying linkages between possible policy actions and desired outcomes [

38]. Epistemic communities provide a key input into the policy process, which is particularly effective in certain institutional structures. In corporatist structures, participation in the policy process is limited to a small number of societal actors who collectively form an epistemic community that has a shared set of values. Members of this community are able to influence the policy agenda and they also provide policy stability, which makes shared methods and values an important factor for a common agenda on which climate policies are being developed.

4.2. Consensus Focused Democratic Institutions

A central element of many consensus democracies is a corporatist institutional structure that allows a more coordinated approach to policy making with a small number of large peak organisations [

25]. This closed shop approach enables the formation of epistemic communities as it substantially limits the number of players that need to be convinced. The potential comparative advantage of consensus democracies also relates to a number of other elements that characterise these countries, such as the “shadow of state regulation” [

5] and a broad acceptance of government regulation due to a history of strong penetration of the state in areas such as the labour market and social policy [

26]. The institutional structures of a consensus democracy are the primary drivers behind political stability and continuity that creates better environmental policies over the long term [

3,

42]. Corporatist institutional arrangements characterised by a strong relationship between large encompassing groups enable decision makers to negotiate policy in a way that is distinctively different from policy making in pluralist, majoritarian democracies [

21]. These groups are integrated into the policy process in a country with a corporatist structure and broaden the basis of policies, which creates a high level of continuity that is required for long-term investments [

43]. Such coalition building locks groups into certain policy directions that further enhance policy progress, which is almost self-reinforcing [

23,

24].

The institutions that enable a broader consensus amongst politicians and society are described by a large number of scholars using different approaches and definitions. This study aims to apply these theories in a combined approach which will allow an assessment of institutional relationships that is broader than the isolated approaches used in many previous studies. It aims to relate one particular institutional feature to socio-economic or more specific policy outcomes.

Democratic systems can largely be divided into two major categories: majoritarian and consensus democracies [

19,

22,

44]. Majoritarian system are characterised by the concentration of power in one-party and minimal winning majority cabinets, a two-party system, non-proportional election systems, interest organisation pluralism, centralised forms of government, unicameral parliaments, constitutional flexibility, absence of judicial review, and executive control of the central bank. Consensus democracies on the other hand are characterised by coalition government, balance between executive and legislative power, proportional representation, interest group corporatism, federalism, bicameralism, constitutional rigidity, judicial review, and independence of the central bank [

44]. These combinations are not a definitive list of characteristics, but an indication of typical elements of countries that can be described as majoritarian or consensus democracies.

Due to its characteristics it could be argued that a majoritarian democracy is decisive and able to implement climate change mitigation measures faster than a consensus focused counterpart. This argument may have some merit when looking at the amendments to the vehicle fuel efficiency standards introduced by Australia, Canada, and the US in recent years. All three countries are typical majoritarian democracies and changes in the standards have been introduced in the US and Australia by Democratic and Labour-led governments, respectively. Canada´s regulation is aligned with the US standards. This shows that change is possible and can be implemented fairly swiftly in majoritarian systems, but this relies on support of the minimal majority, which may change and with that, possibly support for the policy. This paper argues that the decisive factor of success for climate change mitigation policies is the reliability of the policy environment over the long term. It challenges the theory that majoritarian democracies are more effective and argues that consensus orientated democracies are more likely to be successful in moving towards sustainable development over the long term. This has become particularly obvious when looking at the high level of political volatility of the position of the United States in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), adopted in 1992 by George H.W. Bush although with watered down targets, followed in 1997 with the Kyoto Protocol as major milestone, first signed and actively supported by Al Gore on behalf of the US administration and then abandoned by the George W. Bush administration. With insufficient parliamentary support, the Obama administration struggled to pass major climate change legislation, but helped championing the Paris Agreement in 2015, from which the Trump administration withdrew in 2017, making it the only country in the world except for Syria and Nicaragua not being part of this global climate change agreement. While sometimes being slow in the adoption of climate policy measures [

45,

46], the EU has maintained a steady and gradually improving approach to climate change mitigation policy that has endured many elections at the member states and EU level. This shows a link between institutional and climate change indicators and provides an indication that consensus democracies can outperform majoritarian democracies by creating a more stable policy environment through more efficient institutional relationships [

19]. It is argued that consensus democracies are even more responsive and decisive than majoritarian systems, at least over the longer term, because of the more coordinated interaction with societal actors [

21]. This positive impact on the stability of the policy environment depends on a number of elements that are characteristic for a country with a corporatist structure, for example: comparatively encompassing interest groups, the ‘shadow of state regulation’, and a broad acceptance of government regulation due to a history of strong penetration of the state in areas such as the labour market and social policy [

4].

Corporatist institutional arrangements are characterised by a strong relationship between large encompassing interest organisations that enable decision makers to negotiate policy in a way that is distinctively different from policy making in pluralist, majoritarian democracies. The difference between corporatist and pluralist institutional arrangements has been studied for many years. However, there is still debate about corporatism creating more positive impacts, in particular on socio-economic performance [

29,

47] as opposed to negative effects [

48,

49]. Corporatist intuitional interaction is considered to have less collective protests and strikes [

50], which gives an indication of political stability. It can be claimed that corporatism is beneficial for climate change policy development if the encompassing groups have vital interests that foster environmentally sustainable policies. These groups are integrated into the policy process in a corporatist country and broaden the basis of policies, which creates a high level of continuity that is required for long-term investments. This coalition building locks groups into certain policy directions that further enhance policy progress, which is almost self-reinforcing [

23,

24]. Based on this analysis consensus oriented democratic institutions and encompassing corporatist structures are considered to be highly relevant factors for the framework presented in this paper.

4.3. European Integration

The interrelations between European and domestic politics and policies create a new dimension for societal and political actors [

51,

52,

53]. The European level opens new opportunities, but potentially also constrains the pursuit of specific political interests. This provides societal actors with an opportunity to advocate for policy measures, for example, climate change mitigation policy measures even if the particular issue has no or little priority on the domestic political agenda [

32]. Even more important are the formal institutions of the European Union, which provide the opportunity for new policy initiatives. They also create a policy environment that is less dependent on national elections and hence less likely to become subject to radical change after an election [

54]. The “logic of appropriateness” [

53] and processes of persuasion in the European Union are mediated by the influence of change agents who persuade others to adjust national interests to the overarching European framework and a European political culture which aims for political consensus and cost-sharing [

32]. The European Union influences climate and energy polices of its member states both directly and indirectly [

30,

51,

52]. Due to its supra-national character, the European Union is a significant policy driver. How much influence this driver has in comparison with, for example, the United Kingdom and Germany. Both are members of the European Union, differ significantly in their level of corporatism, but have similar developments in energy intensity in the transport sector. Hence it could be assumed that membership in the European Union is a contributing factor to more political continuity. Considering the role of the European Union for example in the area of EU-wide fuel efficiency regulations, it is fair to say that European institutions are not only a contributing, but a driving factor to more political continuity in this policy area.

Integration into the European Union as a factor of political continuity touches on various concepts, in particular rational choice institutionalism and constructivist institutionalism (see for example: [

32,

51,

52]. In contrast, participation in international forums and international governance structures, most notably the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) influences national climate policy strategies, but to a much smaller degree as the withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement and the Kyoto Protocol before showed. Pressures on countries for acting on climate change in international negotiations may vary depending on the country’s role in the international community and its track record on climate change policies. This may influence a country’s motivation to implement policies that curb emissions. International agreements are relatively weak compared to the supranational structure of the EU. Hence, it is assumed that the integration into international agreements only has little influence on the ability of countries to deliver on long-term climate change policy goals, while the integration into supranational structures (as of now only the EU is a supranational body) does play a significant role for the governance framework presented in this paper.

4.4. Influence of Centre-Left Parties and Green Parties

Several authors suggest that the strength of centre-left and green parties has a significant impact on the effectiveness of environmental policies [

53,

54,

55,

56]. Green parties’ central, if not defining, political objective is environmental protection. Hence, their political representation and influence in Parliament and government is likely to impact positively on climate change policies. Centre-left parties are the more likely coalition partners for Green parties and also tend to be more interventionist in their policy making [

56,

57,

58]. Several papers indicate that the dependence on centre-left and Green party-strength is less relevant for policy outcomes than the higher level of continuity in corporatist countries and consensus democracies. This could be linked to the integration of climate change mitigation and energy security as important policy objectives by the societal actors. With regard to the framework to be developed in this paper, a reliance on Centre-Left Parties and Green Parties to adopt and implement climate change policies would indicate a potential for swifter action, but would bear the risk of political volatility if policies are not based on a broader societal and political consensus.

5. Example: Vehicle Fuel Efficiency Regulation in the EU and US

To illustrate the role of institutional factors, this section provides an example from one of the key policy interventions to improve the efficiency of the light-duty vehicle fleet—fuel efficiency standards. This type of regulation aims to ensure a supply of efficient vehicles and, even more importantly, aim to limit the level of fuel consumption throughout the vehicle fleet.

The USA was the first country to introduce vehicle fuel economy standards, in as early as 1975, just two years after the first oil crisis, in the form of the US Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standard, which requires car manufacturers to meet sales-weighted average fuel economy standards for light vehicles sold domestically. This mandatory standard was effective in improving vehicle fuel efficiency for around a decade, with the fleet-average fuel economy of passenger cars rising from approximately 15 miles per gallon (15.68 L/100 km) in 1975 to approximately 28 mpg by 1989 (8.4 L/100 km). After oil prices recovered in the 1980s and policy-makers’ attention in this area decreased, so did the effectiveness of the CAFE standards. A number of factors contributed to this, most notably that CAFE standards remained unchanged for more than two decades and failed to include light trucks (SUVs). In 2009, when the political environment was more favourable to policy action in this area, the Obama administration adopted a uniform federal standard that required an average fuel economy standard of 35.5 miles per US gallon (6.63 L/100 km; 42.6 mpg‑

imp) by 2016 with an extended target being adopted by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) of an average of 36 miles per gallon by 2025 for cars and light trucks, which was adopted just days before the new administration took office. However, one of the very early steps in the Trump administration’s term was a review of EPA standards and regulations and the Clean Power Plan, which may well lead to a “review, and if necessary, revise or rescind” regulations that may place “unnecessary, costly burdens on coal-fired electric utilities, coal miners, and oil and gas producers” [

58].

The EU moved from voluntary arrangements with the automobile industry to regulation later than the US. The Regulation EC 443/2009 was based on a target of 120 g CO

2/km for the European car industry by 2015 and an extended target was adopted of 95 g/km of CO

2 by 2021 [

59]. While the regulations have several shortfalls, and are in some respects (e.g., vehicle testing) weaker than their US counterparts, there is a constant process to improve and upgrade these regulations and supporting measures [

59]. Considering that the responsibility for these regulations lies at the European Union level, partisan considerations are less of a relevant factor as members of the European Commission and the European Council are from various political parties. The approach to integrate European peak organisations early in the policy process leads to several concessions, but also to a broader coalition on which decisions are being based. Energy efficiency regulations need to be based on a durable and stable policy and political environment as they require large, long-term investments into research and innovation. A structured non-partisan approach that incorporates the perspectives of peak organisations representing relevant societal and economic actors is more likely to create this stable policy environment [

34]. In the specific case of vehicle fuel efficiency, the lower levels of the historic emissions and standards in the EU may be one indication of continued and sustained policy progress. These targets are enshrined in EU legislation that went through an extensive consultation process and was adopted by the broad majority in the European Parliament and among the EU member states in European Council. The relatively strong targets adopted in the US adopted through executive action have no legislative backing and may be revised or repealed as part of the broader move of the Trump administration to roll back environmental and climate change policy.

6. Example: Urban Mobility Solutions in India and Brazil

Political volatility can affect national and local level policy environments. While there has been extensive work carried out on the relationship between institutional structures and socio-economic outcomes in many industrialized countries, similar analyses for emerging economies are still rare. The urban mobility SOLUTIONS network has worked with several key emerging economies, including India and Brazil. The two countries are dynamic democracies that face substantial challenges from rapid urbanization and economic development.

Brazil is the largest economy in Latin America and has put forward a relatively ambitious Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) as part of the UNFCCC process, i.e., reducing CO

2 emissions by 37% reduction below 2005 levels by 2025 [

60]. On the federal level, however, there are a number of inconsistencies in the policy approach, such as the halving of the budget of the Ministry for the Environment [

61]. On the local level, there are a number of cities that have been working very proactively on sustainable mobility solutions for many years, such as the city of Curitiba that established the world’s first Bus Rapid Transit system. As part of the SOLUTIONS project, the city of Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais, Brazil) worked with partners on the implementation of several sustainable urban mobility measures, such as traffic calming, low/speed zones, and promoting cycling in the city. While Belo Horizonte (population: 2.4 million, with 5.7 million in the official metropolitan area) has seen a seismic political shift in 2016, there is some stability in the city’s policy environment, which is building on a coalition between staff within the local government administration who remained largely in their positions and an active civil society that coordinates well among the various interest groups working on different policy objectives (air quality, safety, access, etc.).

India, the largest democracy in the world, has also seen rapid economic development and urbanization with some of the challenges deriving from such air pollution and road congestion being particularly prominent. The Government of India has set out a number of programs at the federal level in the areas of renewable energies, transport, and urban development. At the local level, city authorities often lack the intuitional capacity or even the mandate to shape the mobility system of the city. The city of Kochi (Kerala, India, population: 2.1 million in the metropolitan area) has also been part of the SOLUTIONS network and has worked on measures to increase the walkability in the city and identify last-mile connectivity solutions linked to the Metro and waterway systems that are being built or upgraded [

62]. While all three levels of government (union, state, and city) have seen political change over the duration of the project, there has been a relative level of stability, which was built again on staff within the administration that remained in their positions, an active civil society, but also the Kochi Metro Rail Ltd. Kochi, India, a legal entity (special-purpose vehicle) tasked to deliver on the Metro Rail project, which effectively acts as a Unified Metropolitan Transport Authority for the city.

7. Analysis

Consensual political institutions may lead to higher levels of policy continuity, which in turn would have positive effects for the success of climate change mitigation strategies in the transport sector. This approach also adopts the theoretical concept of “encompassing organisations” [

20] and examines the relationships between political and societal actors and their ability or inability to negotiate policies that are based on broad majorities in both politics and society. Multiparty coalition governments with proportional representation and negotiation can be more effective in lowering unemployment and inflation and can create a more favourable socio-economic environment [

21]. Lijphard and Crepaz provide conceptual frameworks and supporting evidence that governments with consensual, inclusive, and accommodative constitutional structures and wider popular cabinet support act more politically responsibly than more majoritarian, exclusionary, and adversarial countries [

20,

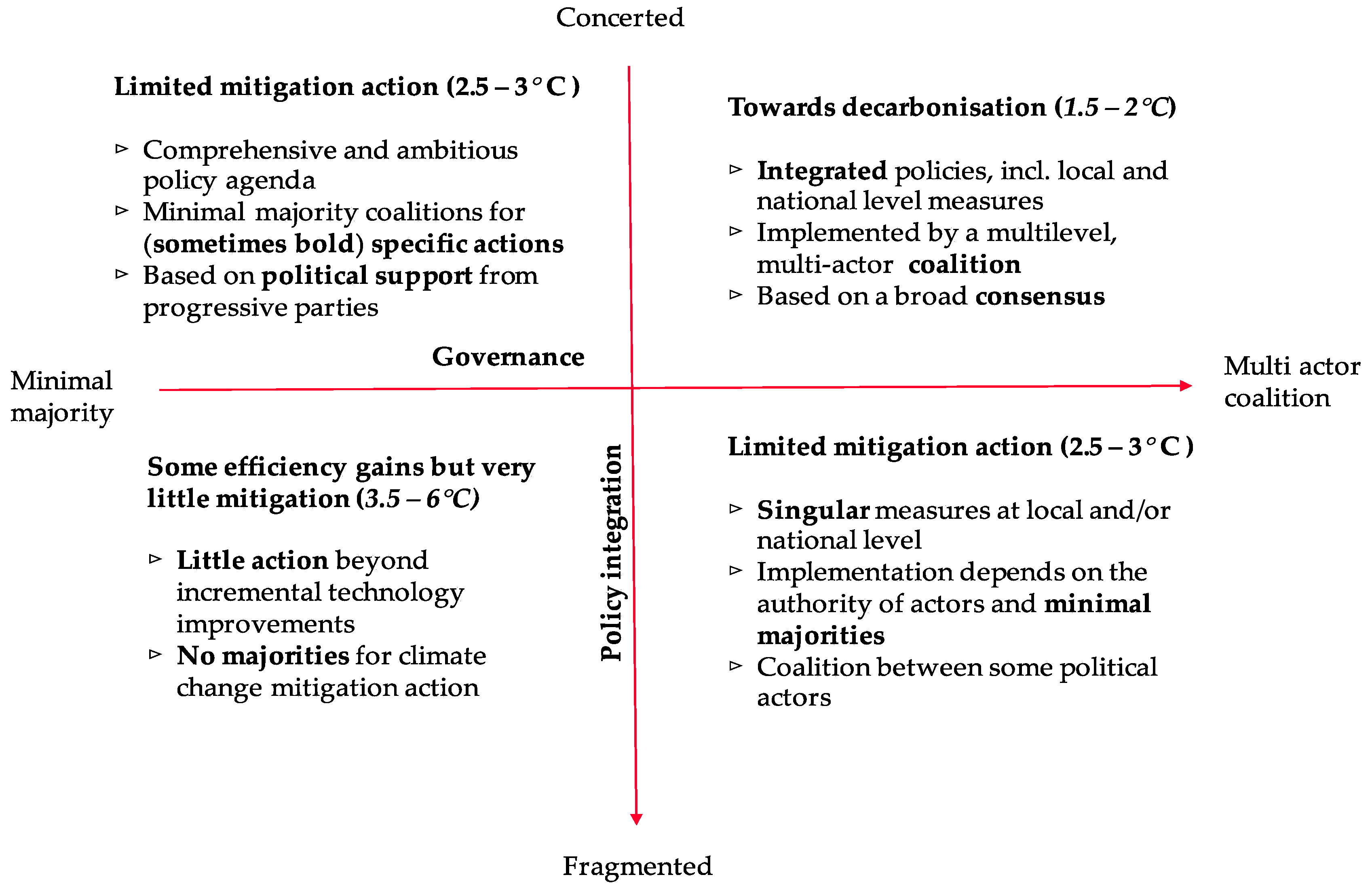

21]. Based on the analysis presented in this paper a transport climate change policy framework can be summarized as shown in

Figure 1, building on aspects of policy integration, coalitions, and institutional structures that influence the policy environment.

The objective of this framework is to show the linkages between policy approaches and governance aspects, stressing the point that an integrated policy approach that addresses the objectives of key actors and stakeholders can help reach a broader consensus on sustainable, low-carbon transport policy. It also aims to highlight that such a consensus and integrated approach is vital to reach global climate change goals.

The indicative pathways of the various governance approaches are in line with the assessment that climate change mitigation in the transport sector will only be able to move towards a 1.5 °C or 2 °C scenario if all available measures at the local and national level are being implemented in an integrated way [

12,

15]. If short-term technology shifts would be sufficient to reach the required greenhouse gas emission reductions, minimal majority coalitions could deliver bold and swift political action if political parties in favour of climate change policies can muster a majority. However, a combined, long-term structural, technological and behavioural transition is needed for the transport sector to actively contribute to global climate change targets and deliver on wider sustainable development benefits. Hence, an integrated policy and governance approach is needed that builds on coalitions and can endure political change to address the complex nature of the transport sector.

8. Conclusions

Sustainable transport policies need an agreement on the necessity for policy intervention and a strategic, coherent, and stable policy environment. Policy interventions within the transport sector, like fuel and vehicle taxation, can be extremely politically sensitive, even more so when they are associated with only one policy issue, such as climate change that may only be relevant for some political actors. They need a powerful political commitment to appear for the transport policy agenda and to remain there ensuring that investments in cost-efficient sustainable mobility measures can endure over the medium to long-term. Maintaining such a stable policy environment is very challenging and highly dependent on political and institutional structures. Among industrialised countries, only the EU and (most of) its member states, Switzerland, and Norway have shown relatively high levels of stability in the area of sustainable and efficient transport policies. Countries such as the US, UK, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia have experienced remarkable shifts in policy priorities and approaches, in particular when related to climate change mitigation. These political and institutional patterns do not re-appear in the same form in many developing and emerging economies. While political tensions and ideologies within the political spectrum, for example in India, Mexico, and Brazil are similar in some policy areas, the close interlink of low-carbon transport policies with other key policy objectives such as air quality, congestion, road safety, and access creates political pressure that allows for a certain level of continuous progress towards sustainable mobility solutions in particular at the local level. This could be a vital contribution to a broader mix of local, national, and (where applicable) supra-national measures that help mitigate political volatility to some extent at the different levels of government and foster policy coherence. Similarly, the cases of India and Brazil show how coalitions can be formed at the local level to provide a certain level of stability in the policy environment.