Fostering Learning in Large Programmes and Portfolios: Emerging Lessons from Climate Change and Sustainable Development

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Failure to incorporate reflexive learning in the process could manifest itself in misguided policy positions and an inability to assess the changing science of climate change, with serious consequences for practitioners and funding, and missed opportunities for sharing lessons for addressing climate change impacts.[4] (p. 630)

[T]ypically funded through a single mechanism and address a common, broad theme, such as community resilience or women’s empowerment. They are implemented across different locations by different organisations, and may target different population groups and employ different interventions, but are grouped together under a common set of high-level objectives, often under a single results framework. Importantly, there is an expectation of some level of interaction between the projects.[13] (p. 4)

- (1)

- Reviewing the theories that have shaped approaches to reflexive learning in large climate change and resilience-building programmes;

- (2)

- Conducting a comparative learning review of the design principles, challenges and lessons emerging from efforts to integrate reflexive learning processes into large, highly distributed climate change and resilience-building programmes for development.

2. Learning as a Unifying Theme in Response to Complexity and Uncertainty

2.1. Theoretical Framings of Learning in Climate and Resilience Programmes

3. Study and Methods

3.1. Introduction to the Review

3.2. Methods

3.3. Linking Learning Theories to Large and Programmes and Portfolios

4. Results

4.1. Framing and Situating Learning in Programme Design

4.2. Learning Themes Emerging from Practice

4.2.1. Joint Enterprise

4.2.2. Mutual Engagement

4.2.3. Shared Repertoire

5. Discussion

5.1. Multi-Project Programmes as Communities of Practice

5.2. Implications for Nested Programmes

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Souza, K.; Kituyi, E.; Harvey, B.; Leone, M.; Murali, K.S.; Ford, J.D. Vulnerability to climate change in three hot spots in Africa and Asia: Key issues for policy-relevant adaptation and resilience-building research. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2015, 15, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). Adaptation Finance Gap Update Report 2015; United Nations Environment Program: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015; Available online: http://web.unep.org/adaptationgapreport/2015 (accessed on 19 January 2017).

- McMichael, A.J.; Butler, C.D.; Folke, C. New visions for addressing sustainability. Science 2003, 302, 1919–1920. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boyd, E.; Osbahr, H. Responses to climate change: Exploring organisational learning across internationally networked organisations for development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Ali, M.B.; Mphepo, G.; Chaves, M.; Macintyre, T.; Pesanayi, T.; Joon, D. Co-designing research on transgressive learning in times of climate change. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 20, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Agency for International Development (USAID). USAID Learning Lab. Available online: https://usaidlearninglab.org/about-usaid-learning-lab (accessed on 13 February 2017).

- United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID). Global Learning for Adaptive Management (GLAM). Available online: https://devtracker.dfid.gov.uk/projects/GB-1-205148 (accessed on 13 February 2017).

- Climate Change Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Climate Change and Social Learning Initiative. Available online: https://ccafs.cgiar.org/climate-change-and-social-learning-initiative (accessed on 13 February 2017).

- Armitage, D.; Marschke, M.; Plummer, R. Adaptive co-management and the paradox of learning. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, A.; Salib, M. Literature Review of the Evidence Base for Collaborating, Learning, and Adapting. 2016. Available online: https://usaidlearninglab.org/library/literature-review-evidence-base-collaborating,-learning,-and-adapting (accessed on 30 October 2016).

- Ornemark, C. ‘Learning Journeys’ for Adaptive Management—Where Does It Take Us? Available online: http://gpsaknowledge.org/knowledge-repository/gpsa-note-learning-journeys-for-adaptive-management-where-does-it-take-us/#.WBc44i2LS70 (accessed on 11 January 2017).

- Kristjanson, P.; Harvey, B.; Van Epp, M.; Thornton, P.K. Social learning and sustainable development. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2014, 4, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffardi, A.B.; Hearn, S. Multi-project programmes: Functions, forms and implications for evaluation and learning. In Methods Lab Working Paper; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2015; Available online: https://www.odi.org/publications/10181-multi-project-programmes-functions-forms-and-implications-evaluation-and-learning (accessed on 19 January 2017).

- Kolb, D. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report; Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pachauri, R.K., Meyer, L.A., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wilby, R.L.; Dessai, S. Robust adaptation to climate change. Weather 2010, 65, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessai, S.; Hulme, M.; Lempert, R.; Pielke, R. Climate prediction: A limit to adaptation? In Adapting to Climate Change: Thresholds, Values, Governance; Adger, N., Lorenzoni, I., O’Brien, K., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; pp. 64–78. [Google Scholar]

- Polasky, S.; Carpenter, S.R.; Folke, C.; Keeler, B. Decision-making under great uncertainty: Environmental management in an era of global change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2011, 26, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ensor, J.; Harvey, B. Social learning and climate change adaptation: Evidence for international development practice. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2015, 6, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.; Ludi, E.; Carabine, E.; Grist, N.; Amsalu, A.; Artur, L.; Bachofen, C.; Beautement, P.; Broenner, C.; Bunce, M.; et al. Planning for an Uncertain Future: Promoting Adaptation to Climate Change through Flexible and Forward-Looking Decision Making. Available online: https://www.odi.org/publications/8255-adaptation-climate-change-planning-decision-making (accessed on 15 September 2016).

- Head, B.W. Wicked problems in public policy. Public Policy 2008, 3, 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbert, M.; Gupta, J. The split ladder of participation: A diagnostic, strategic, and evaluation tool to assess when participation is necessary. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 50, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Turner, N.J. Knowledge system resilience. Hum. Ecol. 2006, 34, 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschakert, P.; Dietrich, K.A. Anticipatory learning for climate change adaptation and resilience. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitas, N.; Reyers, B.; Cundill, G.; Prozesky, H.E.; Nel, J.L.; Esler, K.J. Fostering collaboration for knowledge and action in disaster management in South Africa. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 19, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbacioglu, S.; Kapucu, N. Organisational Learning and Self-adaptation in Dynamic Disaster Environments. Disasters 2006, 30, 212–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkiss, P.; Hunt, A.; Savage, M. Early Value-for-Money Adaptation: Delivering VfM Adaptation Using Iterative Frameworks and Low-Regret Options; Global Climate Adaptation Partnership (GCAP) for Evidence on Demand: London, UK, 2014. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/338360/Early-VfM-Toolkit.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2016).

- Gonsalves, A. Lessons learned on consortium-based research in climate change and development. In CARIAA Working Paper #1; International Development Research Centre: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014; Available online: https://idl-bnc.idrc.ca/dspace/bitstream/10625/52501/1/IDL-52501.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2016).

- Rodela, R. The social learning discourse: Trends, themes and interdisciplinary influences in current research. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 25, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diduck, A. The learning dimension of adaptive capacity: Untangling the multi-level connections. In Adaptive Capacity and Environmental Governance; Armitage, D., Plummer, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 199–221. [Google Scholar]

- Vinke-de Kruijf, J.; Pahl-Wostl, C. A multi-level perspective on learning about climate change adaptation through international cooperation. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, L. Rethinking ‘organizational’ learning. In Dimensions of Adult Learning: Adult Education and Training in a Global Era; Foley, G., Ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: London, UK, 2004; pp. 201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Lindeman, E. The Meaning of Adult Education; New Republic, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress; The Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed; Penguin Books: London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, G. Learning in Social Action: A Contribution to Understanding Education and Training; Zed Books: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jordi, R. Reframing the concept of reflection: Consciousness, experiential learning, and reflective learning practices. Adult Educ. Q. 2011, 61, 181–197. [Google Scholar]

- Boud, D.; Keogh, R.; Walker, D. What is reflection in learning? In Reflection: Turning Experience into Learning; Routledge Falmer: London, UK, 1985; pp. 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C.; Schön, D. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective; Addison Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C. Knowledge for Action. A Guide to Overcoming Barriers to Organizational Change; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. Communities of practice and social learning systems. Organization 2000, 7, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Paas, L.; Parry, J.-E. Understanding Communities of Practice: An Overview for Adaptation Practitioners. Available online: http://www.seachangecop.org/node/1935 (accessed on 19 January 2017).

- Cundill, G.; Roux, D.J.; Parker, J.N. Nurturing communities of practice for transdisciplinary research. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyall, C.; Bruce, A.; Marsden, W.; Meagher, L. The role of funding agencies in creating interdisciplinary knowledge. Sci. Public Policy 2013, 40, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, P.W.; Graham, L.J. The ‘Russian doll’ approach: Developing nested case-studies to support international comparative research in education. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2013, 36, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundill, G.; Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Mukute, M.; Belay, M.; Shackleton, S.; Kulundu, I. A reflection on the use of case studies as a methodology for social learning research in sub Saharan Africa. NJAS Wageningen J. Life Sci. 2014, 69, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raybould, J.; Buffardi, A.B.; Pasanen, T.; Harvey, B.; Clarke, J.; Pollard, A. Fostering a culture of evidence-based learning in large programmes and portfolios. In Proceedings of the United Kingdom Evaluation Society Annual Conference 2016, London, UK, 27–28 April 2016.

- Rog, D.J. Designing, managing, and analyzing multisite evaluations. In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation, 2nd ed.; Wholey, J.S., Hatry, H.P., Newcomer, K.E., Eds.; Jossey Bass/Wiley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 208–236. Available online: http://www.themedfomscu.org/media/Handbook_of_Practical_Program_Evaluation.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2017).

- Coe, J.; Majot, J. Monitoring, Evaluating and Learning in NGO Advocacy: Findings from Comparative Policy Advocacy MEL Review Project. 2013. Available online: https://www.oxfamamerica.org/static/media/files/mel-in-ngo-advocacy-full-report.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2017).

- Collaborative Adaptation Research Initiative in Africa and Asia (CARIAA). M&E and Learning Strategy; International Development Research Centre: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pathways to Resilience in Semi-Arid Economies (PRISE). M&E Strategy; Internal Document; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Building Resilience and Adaptation to Climate Extremes and Disasters (BRACED). BRACED Knowledge Manager: Our Vision for Building Resilience to Climate Extremes and Disasters; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Climate Change Compass. Inception Report; IMC Worldwide and Itad.: London, UK, 2016.

- Smith, M.L.; Reilly, K. (Eds.) Open Development: Networked Innovations in International Development; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014.

- Pathways to Resilience in Semi-Arid Economies (PRISE). PRISE Memorandum of Understanding; Internal Programme Document; Pathways to Resilience in Semi-Arid Economies: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, B.; Langdon, J. Re-imagining capacity and collective change: Experiences from Senegal and Ghana. IDS Bull. 2010, 41, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coakes, E.; Smith, P. Developing communities of innovation by identifying innovation champions. Learn. Org. 2007, 14, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschakert, P.; Das, P.J.; Pradhan, N.S.; Machado, M.; Lamadrid, A.; Buragohain, M.; Hazarika, M.A. Micropolitics in collective learning spaces for adaptive decision making. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 40, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valters, C.; Cummins, C.; Nixon, H. Putting Learning at the Centre: Adaptive Development Programming in Practice; ODI Working Paper; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.odi.org/publications/10367-putting-learning-centre-adaptive-development-programming-practice (accessed on 20 January 2017).

| Definition | Contribution to Learning | |

|---|---|---|

| Joint enterprise | Shared understanding of the goals or expectations that bind members together. Continuously negotiated and to which all members feel accountable. | Determines the level of investment and learning energy within the community. |

| Mutual engagement | Brings members together across their inherent diversity. Promotes the establishment of norms and collaborative relationships. | Determines the depth of social capital, trust, and reciprocity within the community upon which learning processes can rest. |

| Shared repertoire | Tools, stories, discourses, born of joint enterprise and mutual engagement, that belong to and define the community. Resources to make meaning of research questions, findings and applications. | Determines the shared ways of understanding that the community can use in reflecting and re-orientating practice. |

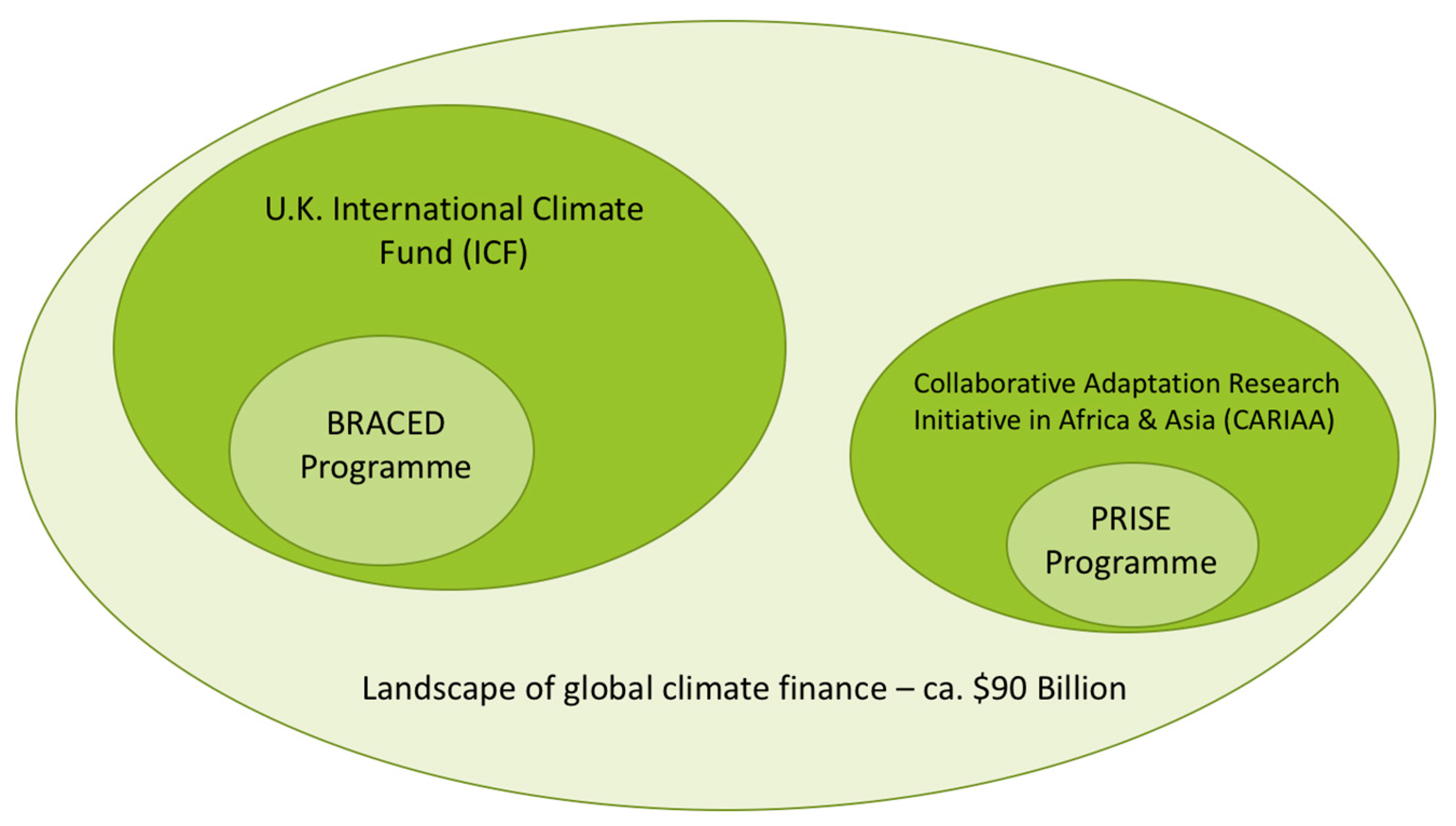

| Initiative/Programme | Funder(s) | Budget | Implementing Partners | No. of Projects | No. of Countries | Duration | Key Themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICF: International Climate Fund | U.K. Government through: DFID (63%); BEIS (35%); Defra (3%) (rounded figures) | £3.87 billion (2011–2015) | Hundreds of partners including multilateral agencies, CSOs, partner governments and other agencies | 200+ being implemented | 35 | From 2011 onwards | Climate change mitigation, resilience, forestry |

| BRACED: Building Resilience and Adaptation to Climate Extremes and Disasters | DFID through the ICF | £140 million (£110 million currently programmed) | 15 implementation consortia and 1 knowledge management consortium, 100+ implementing organisations | 15 | 13 | 3 years (plus project development and inception phase) | Resilience including: Climate and weather information, social protection, governance and natural resource management, gender |

| CARIAA: Collaborative Adaptation Research Initiative in Africa and Asia | DFID and International Development Research Centre (IDRC) | CAD$70 million (£43.3 m (conversion rate at time of writing) | 4 consortia, 18 core consortium partners and 40+ collaborating institutions. | The 4 consortia are considered the core “projects” | 16 | 7 years (2 years development and inception, 5 years implementation) | Vulnerability in climate change hot spots areas |

| PRISE: Pathways to Resilience in Semi-Arid Economies | DFID and IDRC through CARIAA | CAD$13.5 million (£8.4 million) | 4 core partner organisations; 3 country research partners | 7 key projects | 6 | 5 years | Inclusive, climate resilient development in semi-arid lands |

| Stated Role of Learning | Participants | Key Learning Mechanisms | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CARIAA | “CARIAA is explicitly designed to capture learning on the process of producing adaptation research and supporting its use in policy and practice. This involves testing the CARIAA Theory of Change through implementation, the findings of which will be used by the CARIAA Team and consortia to inform their program strategies, as well as produce learning on processes of wider interest to the sector […]. The learning framework does not aim at measuring performance for the sake of accountability, but to learn more about how the program model is contributing to a particular set of outcomes” [53] (p. 18). | Programme staff at IDRC; members of all four consortia; CARIAA advisory committee members | Facilitated annual learning review (in-person) with all consortia; thematic working groups (in-person/online); online knowledge-sharing platform |

| PRISE | Learning is one of the main purposes of information collected through the [monitoring and evaluation] strategy. It should help PRISE members, other CARIAA members and the wider research community better understand the effectiveness of the programme. “Learning will particularly focus on the more uncertain elements of the programme—i.e., the stakeholder engagement and research uptake. Insights from learning will in turn feed back into the programme management cycle” [54]. | Consortium members and IDRC programme staff | Annual meeting (in-person); project and country-level meetings (in-person/online); thematic working groups (in-person/online); CARIAA’s knowledge platform |

| BRACED | “Learning, reflection and iteration are core features of effective knowledge production and management, and inform the way we design and implement all of our activities aimed at building resilience. We do this through: working with Implementing Partners to support action-reflection cycles and document learning around specific implementation processes; conducting evaluation and research within and beyond BRACED to identify the essential building blocks that enable resilient systems to develop and sustain themselves; and testing qualitative and quantitative methods to monitor and measure changes in resilience” [55]. | Knowledge manager team; members of all consortia; other resilience initiatives | Facilitated annual learning events (in-person); thematic dialogues (online/in-person); action research by knowledge manager and consortia; online knowledge sharing platform; evaluations |

| ICF | The Compass programme aims to capture insights from ICF-funded programmes to inform the design and development of programmes that are timely, relevant and effective in tackling climate change and reducing poverty. Ultimately, we want to learn from the experience of the ICF portfolio to inform and improve organisational decision-making. Our approach focuses on understanding why, how, in which circumstances and for which groups of people programmes are more or less effective. | DFID programme managers; policy advisers and other decision-makers; the Compass team | Co-development of learning questions; facilitated collaborative learning approaches to support critical reflection (online/in-person); realist evaluation [56] |

| Joint enterprise |

|

| Mutual engagement |

|

| Shared Repertoire |

|

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harvey, B.; Pasanen, T.; Pollard, A.; Raybould, J. Fostering Learning in Large Programmes and Portfolios: Emerging Lessons from Climate Change and Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2017, 9, 315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9020315

Harvey B, Pasanen T, Pollard A, Raybould J. Fostering Learning in Large Programmes and Portfolios: Emerging Lessons from Climate Change and Sustainable Development. Sustainability. 2017; 9(2):315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9020315

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarvey, Blane, Tiina Pasanen, Alison Pollard, and Julia Raybould. 2017. "Fostering Learning in Large Programmes and Portfolios: Emerging Lessons from Climate Change and Sustainable Development" Sustainability 9, no. 2: 315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9020315

APA StyleHarvey, B., Pasanen, T., Pollard, A., & Raybould, J. (2017). Fostering Learning in Large Programmes and Portfolios: Emerging Lessons from Climate Change and Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 9(2), 315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9020315