Social Support and Commitment within Social Networking Site in Tourism Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. SNS Use in the Tourism Context

2.2. Commitment to SNS

2.3. Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions

2.4. Perceived Social Support

2.5. Satisfaction with Tourism Experience

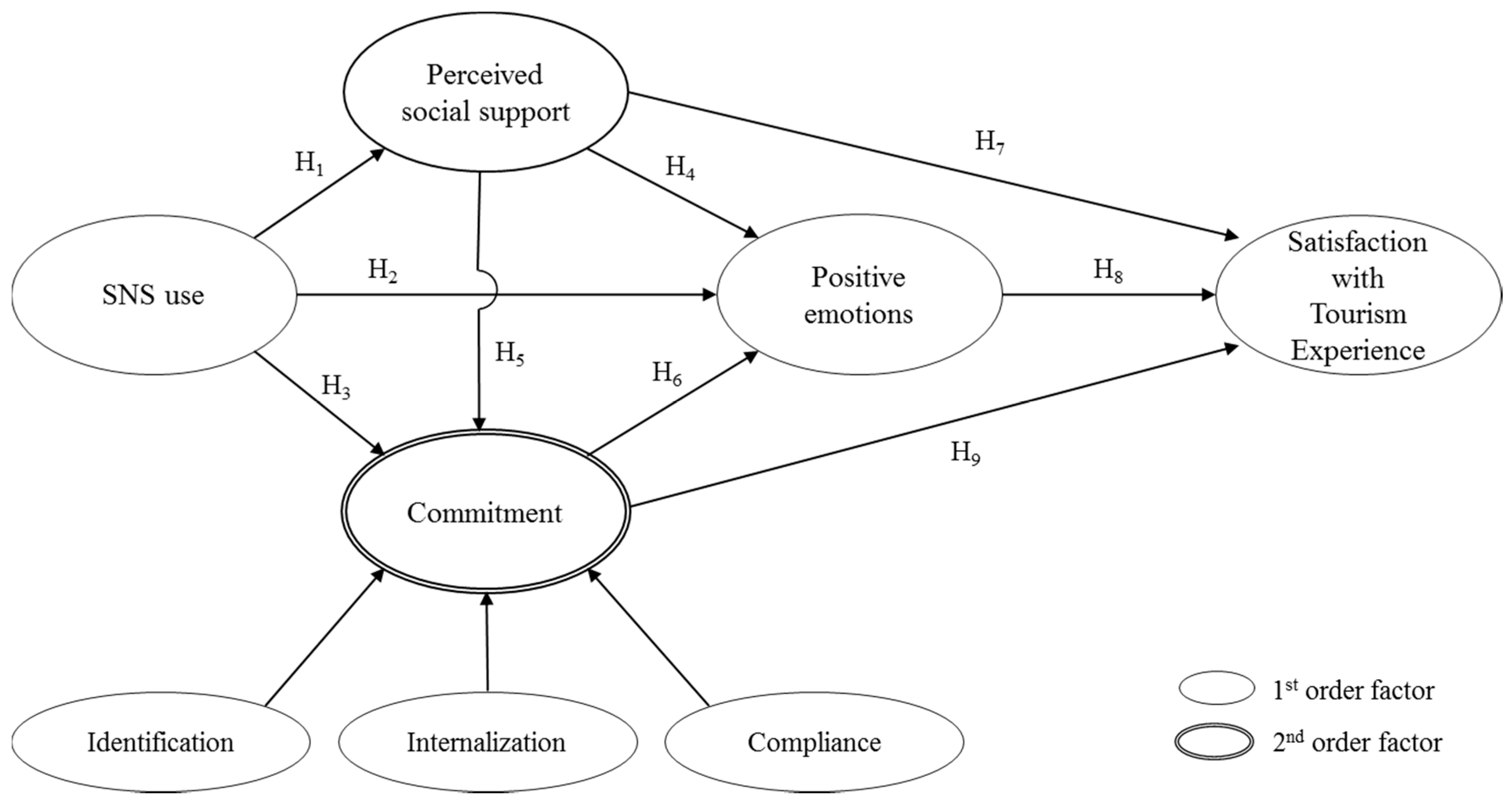

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

3.1. SNS Use

3.2. Perceived Social Support

3.3. Commitment

3.4. Satisfaction with Tourism Experience

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Instrument Development

4.2. Data Collection

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Measurement Model

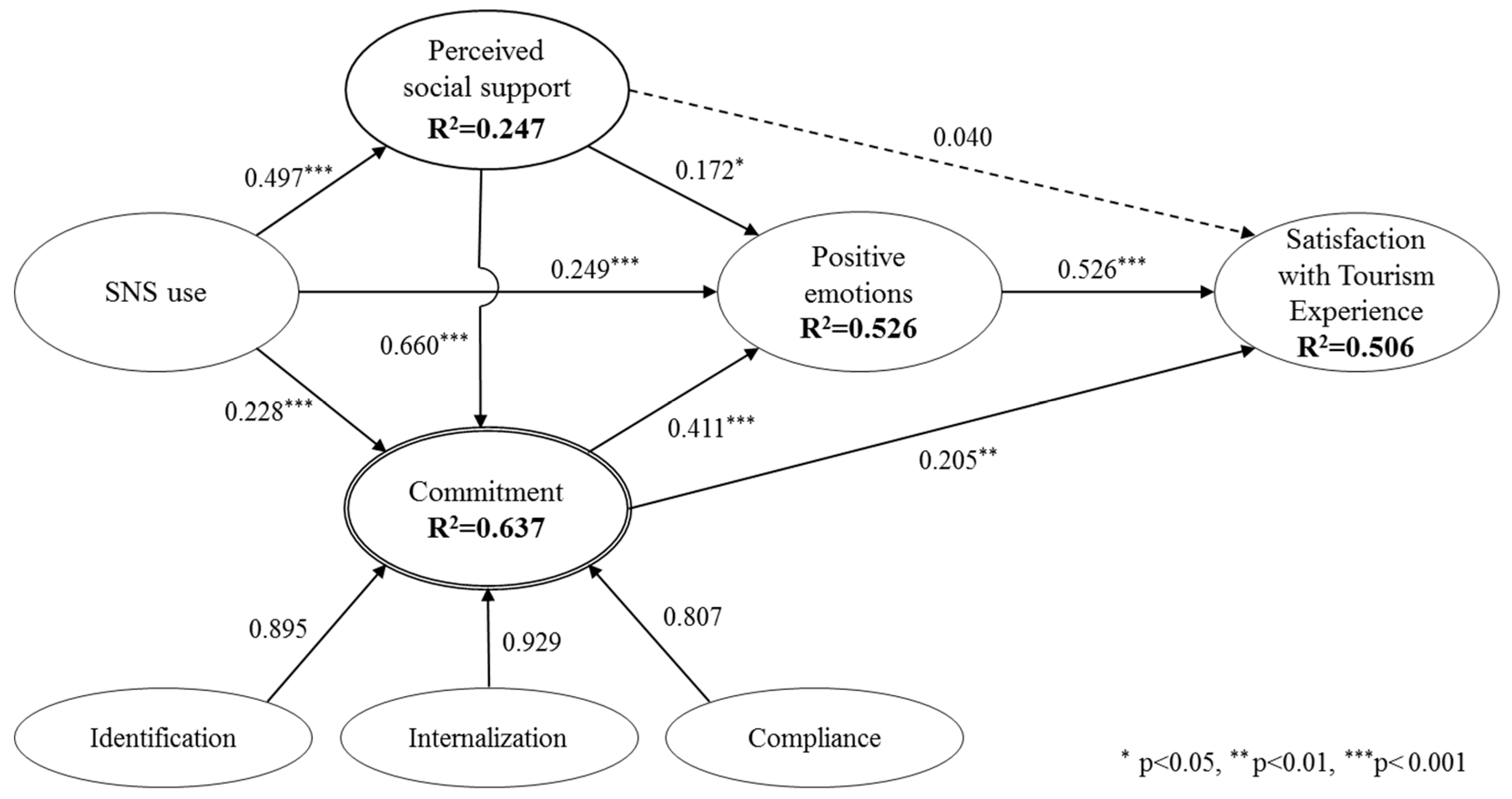

5.2. Structural Model

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Future Research

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiang, Z.; Gretzel, U. Role of social media in online travel information search. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Law, R. Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—The state of eTourism research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Kang, M.; Lee, W. Differences in consumer-generated media adoption and use: A cross-national perspective. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2008, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.J.; Ozkaya, E.; LaRose, R. How does online social networking enhance life satisfaction? The relationships among online supportive interaction, affect, perceived social support, sense of community, and life satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 30, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akar, E.; Topçu, B. An examination of the factors influencing consumers’ attitudes toward social media marketing. J. Internet Commer. 2011, 10, 35–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackshaw, P. The Pocket Guide to Consumer Generated Media. 2005. Available online: http://www.clickz.com/showPage.html?page=3515576 (accessed on 11 November 2017).

- Statista. 2017. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/278414/number-of-worldwide-social-network-users/ (accessed on 20 October 2017).

- Cheung, C.M.; Chiu, P.Y.; Lee, M.K. Online social networks: Why do students use facebook? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, K.E.; Waller, R. Social networking goes abroad. Int. Educ. 2007, 16, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.C. Online social network acceptance: A social perspective. Internet Res. 2011, 21, 562–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.E.R. The Facebook paths to happiness: Effects of the number of Facebook friends and self-presentation on subjective well-being. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 14, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalpidou, M.; Costin, D.; Morris, J. The relationship between Facebook and the well-being of undergraduate college students. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 14, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitak, J.; Ellison, N.B.; Steinfield, C. The ties that bond: Re-examining the relationship between Facebook use and bonding social capital. In Proceedings of the IEEE 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Kauai, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2011; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, D.; Law, R.; Van Hoof, H.; Buhalis, D. Social media in tourism and hospitality: A literature review. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellarocas, C. The digitization of word of mouth: Promise and challenges of online feedback mechanisms. Manag. Sci. 2003, 49, 1407–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Schuett, M.A. Determinants of sharing travel experiences in social media. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Tussyadiah, I.P. Social networking and social support in tourism experience: The moderating role of online self-presentation strategies. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Zhong, D. Using social network analysis to explain communication characteristics of travel-related electronic word-of-mouth on social networking sites. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, R.; Baggio, R.; Piattelli, R. The effects of online social media on tourism websites. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2011; Law, R., Fuchs, M., Ricci, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Park, N.; Kee, K.F.; Valenzuela, S. Being immersed in social networking environment: Facebook groups, uses and gratifications, and social outcomes. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 729–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Basu, C.; Hsu, M.K. Exploring motivations of travel knowledge sharing on social network sites: An empirical investigation of US college students. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitas, O.; Yarnal, C.; Adams, R.; Ram, N. Taking a “peak” at leisure travelers’ positive emotions. Leis. Sci. 2012, 34, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwortnik, R.J.; Ross, W.T. The role of positive emotions in experiential decisions. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2007, 24, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, C.W.; Wyer, R.S., Jr. Affect, appraisal, and consumer judgment. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filep, S.; Deery, M. Towards a Picture of Tourists’ Happiness. Tour. Anal. 2010, 15, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pühringer, S.; Taylor, A. A practitioner’s report on blogs as a potential source of destination marketing intelligence. J. Vacat. Mark. 2008, 14, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Park, S.; Fesenmaier, D.R. The role of smartphones in mediating the touristic experience. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Fesenmaier, D.R.; Johnson, S.L. The effect of feedback within social media in tourism experiences. In Design, User Experience, and Usability. Web, Mobile, and Product Design; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 212–220. [Google Scholar]

- Kelman, H.C. Compliance, identification, and internalization: Three processes of attitude change. J. Confl. Resolut. 1958, 2, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Nam, K.; Koo, C. Examining Information Sharing in Social Networking Communities: Applying Theories of Social Capital and Attachment. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, B.J.; Zhang, M.; Sobel, K.; Chowdury, A. Twitter power: Tweets as electronic word of mouth. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 2169–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Bowen, J.T.; Makens, J.C. Marketing for Hospitality and Tourism; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, B.; MacLaurin, T.; Crotts, J.C. Travel blogs and the implications for destination marketing. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.C.; Kim, Y. Determinants of consumer engagement in electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) in social networking sites. Int. J. Advert. 2011, 30, 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Sigala, M.; Xiang, Z.; Koo, C. Smart tourism: Foundations and developments. Electron. Mark. 2015, 25, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, S.; Sellitto, C.; Cox, C.; Buultjens, J. Trust perceptions of online travel information by different content creators: Some social and legal implications. Inf. Syst. Front. 2011, 13, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, K.H.; Lee, Y.; Gretzel, U.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Trust in travel-related consumer generated media. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Höpken, W., Gretzel, U., Law, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.J.; Lee, C.K.; Bonn, M. The effect of social capital and altruism on seniors’ revisit intention to social network sites for tourism-related purposes. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Han, H. The relationship among tourists’ persuasion, attachment and behavioral changes in social media. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 123, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, K.; Kim, T.T.; Karatepe, O.M.; Lee, G. An exploration of the factors influencing social media continuance usage and information sharing intentions among Korean travellers. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, H.J.; Molloy, J.C.; Brinsfield, C.T. Reconceptualizing workplace commitment to redress a stretched construct: Revisiting assumptions and removing confounds. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 130–151. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Li, H. Understanding mobile SNS continuance usage in China from the perspectives of social influence and privacy concern. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 37, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, Y.; Galletta, D. A multidimensional commitment model of volitional systems adoption and usage behavior. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 22, 117–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.C.; Choi, S.M. Electronic word-of-mouth in social networking sites: A cross-cultural study of the United States and China. J. Glob. Mark. 2011, 24, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dholakia, U.M.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Pearo, L.K. A social influence model of consumer participation in network-and small-group-based virtual communities. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2004, 21, 241–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; King, L.; Diener, E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 803–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, E.L. Levels of analysis and the organization of affect. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 247–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijda, N.H. The Laws of Emotion; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, H.; Willming, C.; Holdnak, A. “We’re Gators... Not Just Gator Fans”: Serious Leisure and University of Florida Football. J. Leis. Res. 2002, 34, 397–425. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S. Love, anthropology and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugade, M.M.; Fredrickson, B.L. Regulation of positive emotions: Emotion regulation strategies that promote resilience. J. Happiness Stud. 2007, 8, 311–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.Y.; Lu, H.P. Why people use social networking sites: An empirical study integrating network externalities and motivation theory. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1152–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom. Med. 1976, 38, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikal, J.P.; Grace, K. Against abstinence-only education abroad: Viewing Internet use during study abroad as a possible experience enhancement. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2012, 16, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, R.D. Social Support, Person-environment Fit, and Coping. In Mental Health and the Economy; Ferman, L.A., Gordus, J.P., Eds.; W E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research: Kalamazoo, MI, USA, 1979; pp. 89–138. [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne, C.D.; Stewart, A.L. The MOS social support survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991, 32, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, B.H.; Bergen, A.E. Social support concepts and measures. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 69, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Hsu, C.H. The impact of customer-to-customer interaction on cruise experience and vacation satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2010, 49, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klooster, E.; Go, F. Leveraging computer mediated communication for social support in educational travel. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Hitz, M., Sigala, M., Murphy, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brent Ritchie, J.R.; Wing Sun Tung, V.; Ritchie, R.J. Tourism experience management research: Emergence, evolution and future directions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 23, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trauer, B.; Ryan, C. Destination image, romance and place experience—An application of intimacy theory in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Huang, S.; Chen, X. Effects of Service Fairness and Service Quality on Tourists’ Behavioral Intentions and Subjective Well-Being. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 290–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhofer, B.; Buhalis, D.; Ladkin, A. A Typology of technology-enhanced tourism experiences. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Jamal, T. Conceptualizing the creative tourist class: Technology, mobility, and tourism experiences. Tour. Anal. 2009, 14, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkhorst, E.; Den Dekker, T. Agenda for co-creation tourism experience research. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriely, N. The tourist experience: Conceptual developments. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.; Pea, R.; Rosen, J. Beyond participation to co-creation of meaning: Mobile social media in generative learning communities. Soc. Sci. Inf. 2010, 49, 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Mediating tourist experiences: Access to places via shared videos. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, N.B.; Steinfield, C.; Lampe, C. The benefits of Facebook “friends”: Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J. Comput. Med. Commun. 2007, 12, 1143–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, K.; Goulet, L.S.; Rainie, L.; Purcell, K. Social Networking Sites and Our Lives; Pew Research Center’s Internet & Americal Life Project: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Volume 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Towards understanding members’ general participation in and active contribution to an online travel community. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-López, E.; Bulchand-Gidumal, J.; Gutiérrez-Taño, D.; Díaz-Armas, R. Intentions to use social media in organizing and taking vacation trips. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Measuring customer value in online collaborative trip planning processes. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2010, 28, 418–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Roth, M.S.; Madden, T.J.; Hudson, R. The effects of social media on emotions, brand relationship quality, and word of mouth: An empirical study of music festival attendees. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.S.; Lee, H. Understanding the role of an IT artifact in online service continuance: An extended perspective of user satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Modeling participation in an online travel community. J. Travel Res. 2004, 42, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.Y.; Buhalis, D. A study of online travel community and Web 2.0: Factors affecting participation and attitude. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2008; Höpken, W., Gretzel, U., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. 267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, R.K.; White, K.M. Predicting adolescents’ use of social networking sites from an extended theory of planned behaviour perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1591–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, C.; Coyne, J.C.; Lazarus, R.S. The health-related functions of social support. J. Behav. Med. 1981, 4, 381–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, J.D.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. The effect of tourism services on travelers’ quality of life. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.W. Social support and life satisfaction. Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabilit. 2006, 10, 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Greenglass, E.R.; Fiksenbaum, L. Proactive coping, positive affect, and well-being: Testing for mediation using path analysis. Eur. Psychol. 2009, 14, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köbler, F.; Riedl, C.; Vetter, C.; Leimeister, J.M.; Krcmar, H. Social Connectedness on Facebook: An explorative study on status message usage. In Proceedings of the 16th Americas Conference on Information Systems, Lima, Peru, 12–15 August 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Klingensmith, C.L. 500 Friends and Still Friending: The Relationship between Facebook and College Students’ Social Experiences. 2010. Available online: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/psychology_honors/22/ (accessed on 11 November 2017).

- Vieno, A.; Santinello, M.; Pastore, M.; Perkins, D.D. Social support, sense of community in school, and self-efficacy as resources during early adolescence: An integrative model. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2007, 39, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manago, A.M.; Taylor, T.; Greenfield, P.M. Me and my 400 friends: The anatomy of college students’ Facebook networks, their communication patterns, and well-being. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 48, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toma, C.L. Affirming the self through online profiles: Beneficial effects of social networking sites. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–15 April 2010; pp. 1749–1752. [Google Scholar]

- Bigné, J.E.; Andreu, L. Emotions in segmentation: An empirical study. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 682–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clore, G.L.; Huntsinger, J.R. How emotions inform judgment and regulate thought. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2007, 11, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N. Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, R.V. E-tribalized marketing?: The strategic implications of virtual communities of consumption. Eur. Manag. J. 1999, 17, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, M.; Hofacker, C.F.; Goldsmith, R.E. The influence of personality on active and passive use of social networking sites. Psychol. Mark. 2011, 28, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V. Determinants of perceived ease of use: Integrating control, intrinsic motivation, and emotion into the technology acceptance model. Inf. Syst. Res. 2000, 11, 342–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.L.; Lin, J.C.C. Acceptance of blog usage: The roles of technology acceptance, social influence and knowledge sharing motivation. Inf. Manag. 2008, 45, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Cha, S.Y.; Park, C.; Lee, I.; Kim, J. Getting closer and experiencing together: Antecedents and consequences of psychological distance in social media-enhanced real-time streaming video. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 1365–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Zach, F.J. The role of geo-based technology in place experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 780–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelman, H.C. Processes of opinion change. Public Opin. Q. 1961, 25, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, M.K.; Thatcher, J.B. Moving beyond intentions and toward the theory of trying: Effects of work environment and gender on post-adoption information technology use. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 427–459. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbing, D.W.; Anderson, J.C. An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. J. Mark. Res. 1988, 25, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, H.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D. A practical guide to factorial validity using PLS-Graph: Tutorial and annotated example. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 16, 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.M.; Kim, Y.; Sung, Y.; Sohn, D. Bridging or Bonding? A cross-cultural study of social relationships in social networking sites. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2011, 14, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utz, S.; Beukeboom, C.J. The role of social network sites in romantic relationships: Effects on jealousy and relationship happiness. J. Comput. Med. Commun. 2011, 16, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Choudhury, M.; Counts, S.; Horvitz, E. Predicting postpartum changes in emotion and behavior via social media. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Paris, France, 27 April–2 May 2013; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 3267–3276. [Google Scholar]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Odeh, K. The role of tourists’ emotional experiences and satisfaction in understanding behavioral intentions. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grappi, S.; Montanari, F. The role of social identification and hedonism in affecting tourist re-patronizing behaviours: The case of an Italian festival. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1128–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palau-Saumell, R.; Forgas-Coll, S.; Sánchez-García, J.; Prats-Planagumà, L. Tourist Behavior Intentions and the Moderator Effect of Knowledge of UNESCO World Heritage Sites the Case of La Sagrada Família. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Prayag, G. Patterns of tourists’ emotional responses, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Items | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SNS use | USE1 | I spent time browsing travel information and tourism experiences shared by others in the SNS. | |

| USE2 | I spent time sharing travel information and my own tourism experiences in the SNS. | ||

| Perceived social support | SUP1 | I can count on the SNS friends for helping me understand things. | |

| SUP2 | I do not feel alone because I have SNS friends. | ||

| SUP3 | I think I can count on the SNS friends for helping me doing something. | ||

| SUP4 | I think I can count on the SNS friends for helping me with my questions. | ||

| Positive emotions | EMO1 | I find using the SNS to be enjoyable. | |

| EMO2 | The actual process of using the SNS is pleasant. | ||

| EMO3 | I have fun using the SNS. | ||

| Commitment | Identification | IDN1 | In general, I am very interested in what the SNS group members think about sharing my knowledge and information through social media. |

| IDN2 | I feel a sense of belonging to the SNS group when I share my knowledge and information through SNS. | ||

| IDN3 | I feel I will fit into the SNS group when I share my knowledge through SNS. | ||

| Internalization | INT1 | The reason I prefer use of SNS is primarily based on the similarity of my values and those represented by the SNS. | |

| INT2 | The reason I prefer SNS to other communication tools is because of its value. | ||

| INT3 | What the use of the system stands for is important for me. | ||

| Compliance | CPL1 | Unless I am rewarded for sharing knowledge and information on SNS in some way, I may spend less time to share knowledge and information. | |

| CPL2 | How hard I work on SNS is directly related to how much I am rewarded. | ||

| CPL3 | In order for me to get the responses I want on SNS, it is necessary to express the right behavior or attitude on social media. | ||

| Satisfaction with tourism experience | EXP1 | My overall evaluation on the most recent destination experience is positive. | |

| EXP2 | My overall evaluation on the most recent tourism experience is favorable. | ||

| EXP3 | I am satisfied with the most recent tourism experience. | ||

| Characteristics | Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 203 | 52.5 |

| Female | 184 | 47.5 | |

| Age | 19–29 | 51 | 13.2 |

| 30–39 | 121 | 31.3 | |

| 40–49 | 106 | 27.4 | |

| 50–59 | 69 | 17.8 | |

| Over 60 | 40 | 10.3 | |

| Education | Middle and high school | 71 | 18.3 |

| Two-year college | 73 | 18.9 | |

| University | 214 | 55.3 | |

| Graduate school | 29 | 7.5 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 265 | 68.5 |

| Single | 120 | 31.0 | |

| No answer | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Occupation | Student | 41 | 10.6 |

| Office worker | 93 | 24.0 | |

| Services | 73 | 18.9 | |

| Technician | 49 | 12.7 | |

| Professional | 24 | 6.2 | |

| Civil servant | 6 | 1.6 | |

| Businessman | 22 | 5.7 | |

| Homemaker | 71 | 18.3 | |

| Other | 5 | 1.3 | |

| Monthly Income | Less than 1 million won * | 22 | 5.7 |

| 1–1.9 million won | 56 | 14.5 | |

| 2–2.9 million won | 92 | 23.8 | |

| 3–3.9 million won | 69 | 17.8 | |

| 4–4.9 million won | 83 | 21.4 | |

| More than 5 million won | 65 | 16.8 | |

| SNS Use | 1–2 times per month | 12 | 3.1 |

| 1–2 times per week | 54 | 14.0 | |

| 1–5 times per day | 156 | 40.3 | |

| 5–10 times per day | 74 | 19.1 | |

| Over 10 times per day | 91 | 23.5 | |

| Average SNS use per day | Less than 30 min | 85 | 22.0 |

| Over 30 min–less than 1 h | 145 | 37.5 | |

| Over 1 h–less than 2 h | 95 | 24.5 | |

| Over 2 h–less than 3 h | 34 | 8.8 | |

| Over 3 h-less than 5 h | 19 | 4.9 | |

| Over 5 h | 9 | 2.3 | |

| Total | 387 | 100.0 | |

| Construct | Composite Reliability | AVE | Cronbach’s α | Mean | STD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNS Use | 0.856 | 0.749 | 0.903 | 4.152 | 1.04 | |

| Perceived Social Support | 0.930 | 0.769 | 0.886 | 4.340 | 1.05 | |

| Positive Emotions | 0.947 | 0.856 | 0.888 | 4.703 | 0.91 | |

| Commitment | Identification | 0.930 | 0.816 | 0.882 | 4.391 | 0.98 |

| Internalization | 0.932 | 0.820 | 0.881 | 4.282 | 1.04 | |

| Compliance | 0.873 | 0.697 | 0.901 | 4.183 | 1.00 | |

| Satisfaction with tourism experience | 0.937 | 0.833 | 0.897 | 4.776 | 0.92 | |

| Items | USE | SUP | IDN | INT | CPL | EMO | EXP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USE 1 | 0.864 ** | 0.398 ** | 0.479** | 0.398 ** | 0.326 ** | 0.528 ** | 0.508 ** |

| USE 2 | 0.867 ** | 0.462 ** | 0.441 ** | 0.466 ** | 0.413 ** | 0.447 ** | 0.385 ** |

| SUP 1 | 0.434 ** | 0.809 ** | 0.628 ** | 0.538 ** | 0.429 ** | 0.558 ** | 0.492 ** |

| SUP 2 | 0.431 ** | 0.859 ** | 0.643 ** | 0.662 ** | 0.470 ** | 0.493 ** | 0.425 ** |

| SUP 3 | 0.429 ** | 0.923 ** | 0.673 ** | 0.663 ** | 0.521 ** | 0.537 ** | 0.442 ** |

| SUP 4 | 0.447 ** | 0.912 ** | 0.655 ** | 0.672 ** | 0.506 ** | 0.563 ** | 0.470 ** |

| IDN 1 | 0.505 ** | 0.631 ** | 0.882 ** | 0.664 ** | 0.502 ** | 0.599 ** | 0.503 ** |

| IDN 2 | 0.484 ** | 0.691 ** | 0.923 ** | 0.697 ** | 0.497 ** | 0.606 ** | 0.502 ** |

| IDN 3 | 0.452 ** | 0.686 ** | 0.904 ** | 0.684 ** | 0.510 ** | 0.606 ** | 0.521 ** |

| INT 1 | 0.432 ** | 0.675 ** | 0.673 ** | 0.894 ** | 0.604 ** | 0.510 ** | 0.484 ** |

| INT 2 | 0.451 ** | 0.627 ** | 0.661 ** | 0.913 ** | 0.574 ** | 0.604 ** | 0.508 ** |

| INT 3 | 0.473 ** | 0.663 ** | 0.716 ** | 0.910 ** | 0.624 ** | 0.614 ** | 0.520 ** |

| CPL 1 | 0.315 ** | 0.421 ** | 0.405 ** | 0.531 ** | 0.859 ** | 0.330 ** | 0.321 ** |

| CPL 2 | 0.376 ** | 0.485 ** | 0.478 ** | 0.558 ** | 0.891 ** | 0.374 ** | 0.326 ** |

| CPL 3 | 0.373 ** | 0.465 ** | 0.505 ** | 0.568 ** | 0.747 ** | 0.461 ** | 0.429 ** |

| EMO 1 | 0.504 ** | 0.553 ** | 0.608 ** | 0.595 ** | 0.424 ** | 0.907 ** | 0.594 ** |

| EMO 2 | 0.523 ** | 0.583 ** | 0.636 ** | 0.597 ** | 0.441 ** | 0.942 ** | 0.629 ** |

| EMO 3 | 0.535 ** | 0.567 ** | 0.611 ** | 0.576 ** | 0.431 ** | 0.926 ** | 0.689 ** |

| EXP 1 | 0.475 ** | 0.477 ** | 0.510 ** | 0.520 ** | 0.431 ** | 0.607 ** | 0.897 ** |

| EXP 2 | 0.450 ** | 0.493 ** | 0.541 ** | 0.513 ** | 0.373 ** | 0.659 ** | 0.927 ** |

| EXP 3 | 0.487 ** | 0.458 ** | 0.489 ** | 0.491 ** | 0.378 ** | 0.624 ** | 0.914 ** |

| Construct | USE | SUP | EMO | IDN | INT | CPL | EXP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USE | 0.865 | ||||||

| SUP | 0.497 ** | 0.877 | |||||

| EMO | 0.560 ** | 0.610 ** | 0.925 | ||||

| IDN | 0.530 ** | 0.740 ** | 0.668 ** | 0.903 | |||

| INT | 0.501 ** | 0.726 ** | 0.636 ** | 0.754 ** | 0.906 | ||

| CPL | 0.428 ** | 0.549 ** | 0.465 ** | 0.555 ** | 0.662 ** | 0.835 | |

| EXP | 0.512 ** | 0.518 ** | 0.689 ** | 0.563 ** | 0.557 ** | 0.430 ** | 0.913 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Estimates | t-Value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | SNS use → Perceived social support | 0.497 | 13.413 | Supported |

| H2 | SNS use → Positive emotions | 0.249 | 5.219 | Supported |

| H3 | SNS use → Commitment | 0.228 | 5.604 | Supported |

| H4 | Perceived social support → Positive emotions | 0.172 | 2.133 | Supported |

| H5 | Perceived social support → Commitment | 0.660 | 18.336 | Supported |

| H6 | Commitment → Positive emotions | 0.411 | 6.427 | Supported |

| H7 | Perceived social support → Satisfaction with tourism experience | 0.04 | 0.531 | Rejected |

| H8 | Positive emotions → Satisfaction with tourism experience | 0.526 | 9.634 | Supported |

| H9 | Commitment → Satisfaction with tourism experience | 0.205 | 2.587 | Supported |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chung, N.; Tyan, I.; Chung, H.C. Social Support and Commitment within Social Networking Site in Tourism Experience. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2102. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9112102

Chung N, Tyan I, Chung HC. Social Support and Commitment within Social Networking Site in Tourism Experience. Sustainability. 2017; 9(11):2102. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9112102

Chicago/Turabian StyleChung, Namho, Inessa Tyan, and Hee Chung Chung. 2017. "Social Support and Commitment within Social Networking Site in Tourism Experience" Sustainability 9, no. 11: 2102. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9112102

APA StyleChung, N., Tyan, I., & Chung, H. C. (2017). Social Support and Commitment within Social Networking Site in Tourism Experience. Sustainability, 9(11), 2102. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9112102