Addressing “Wicked Problems” through Governance for Sustainable Development—A Comparative Analysis of National Mineral Policy Approaches in the European Union

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. EU Policy Challenges and Responses to the Sustainable Mineral Supply

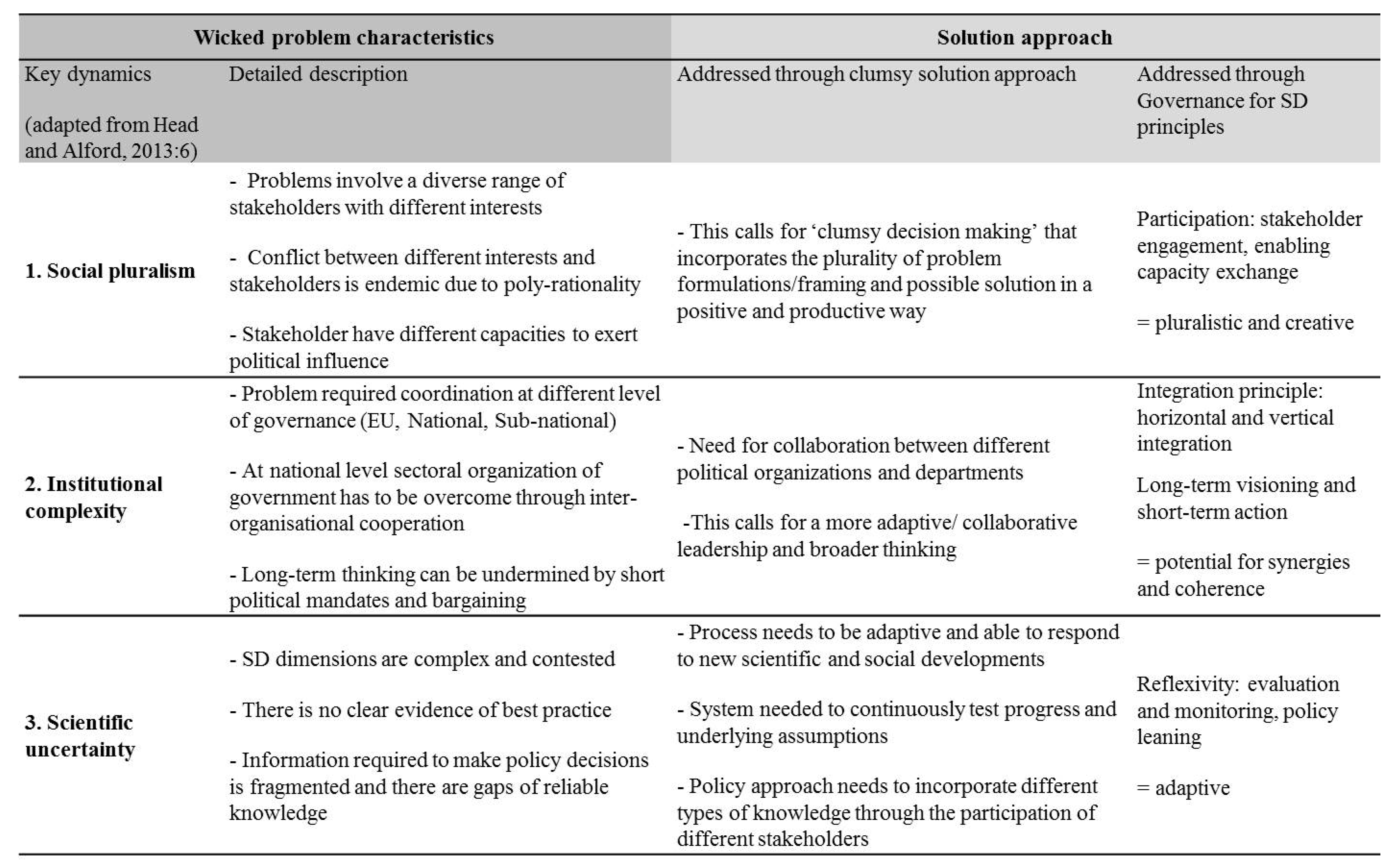

3. “Wicked Problems” and Their “Clumsy” Solutions

4. Governance for SD Principles as a Clumsy Solution Approach for Sustainable Minerals Supply

- (1)

- Are governance for SD principles an intrinsic part of NMS?

- (2)

- To what extent do different ministries collaborate, and what are the processes and mechanisms that define their involvement?

- (3)

- To what extent do NMS integrate non-governmental actors in design and implementation?

- (4)

- How comprehensive and elaborated is the translation of long-term planning into individual actions?

- (5)

- To what degree do NMS include policy assessment tools?

5. Methods

- A Multiple single-outcome study [65] (pp. 710–713) that focuses on investigating within-case (different governance for SD features within NMS) and across-case evidence (comparisons of 5 NMS). This, ultimately, gives insights on the multiple (range of phenomena i.e., features characterising governance for SD) single outcome (governance for SD).

- Small-N qualitative comparisons that take into account the complexity of underlying dynamics and complex configurations of factors within a particular context [66] (p. 301).

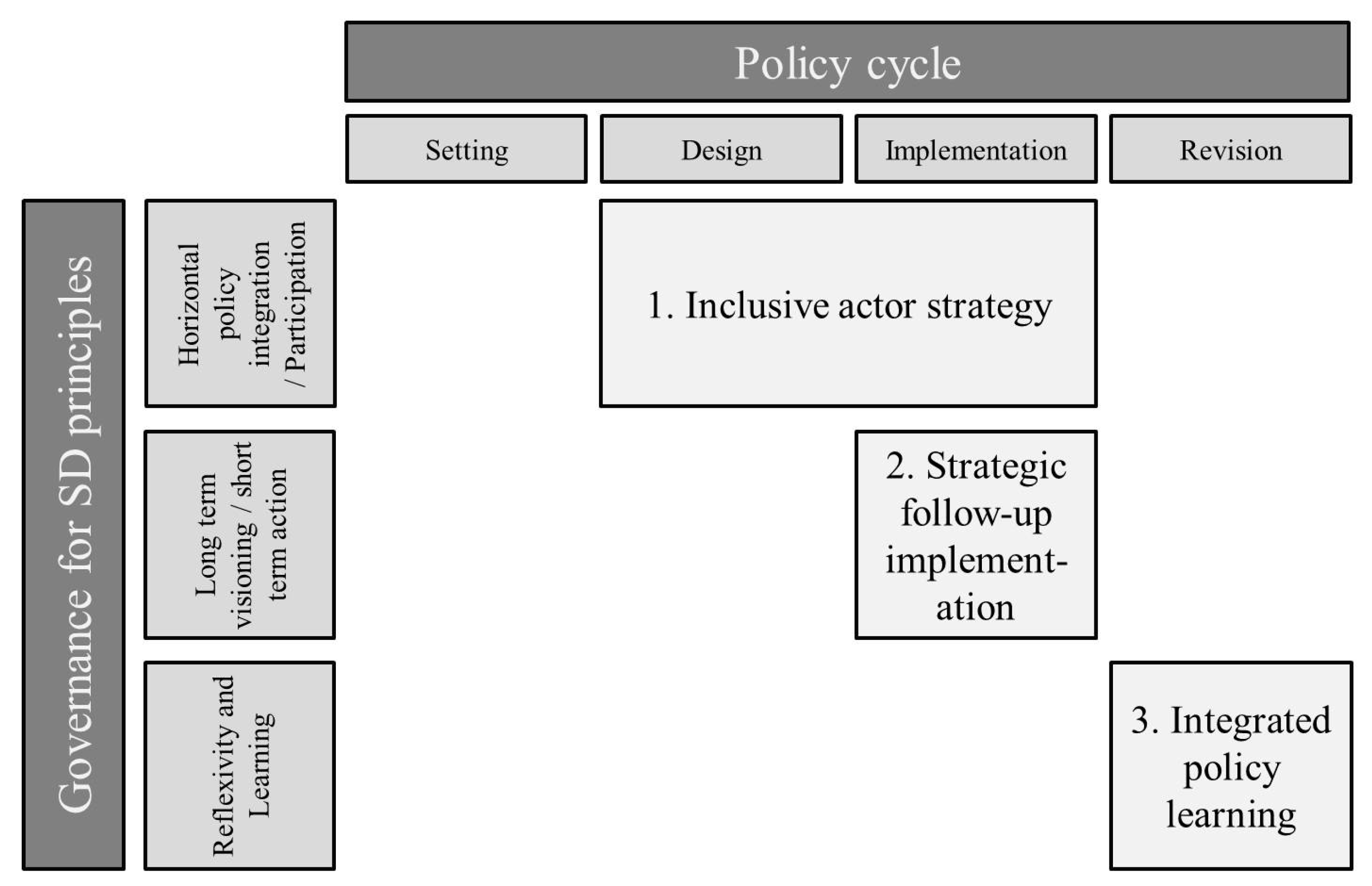

- Key feature 1: Inclusive actor strategy (related to principles: horizontal policy integration and participation);

- Key feature 2: Strategic follow-up implementation (related to principle: long-term visioning and short-term action);

- Key feature 3: Integrated policy learning (related to principle: reflexivity and learning).

- “Inclusive actor strategy” investigates government actor (category 1) and Non-government actor (category 2) involvement during the NMS design phase;

- “Strategic follow-up implementation” stresses the degree to which concrete follow up actions are foreseen (category 1) and to what extent time frames for implementation are linked to them (category 2); and

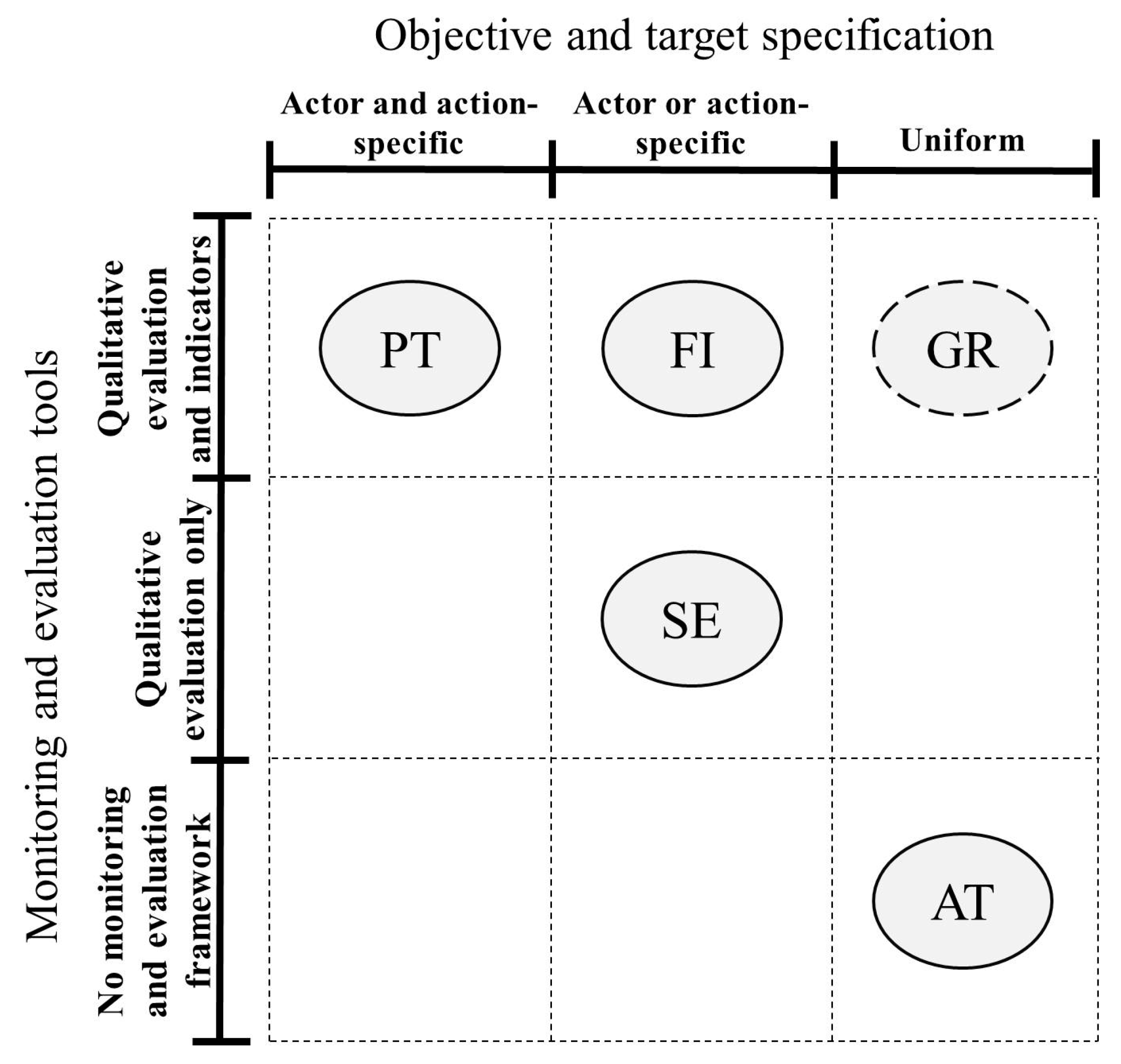

- “Integrated policy learning” deals with the degree of goal and target specification (category 1), as well as the availability of policy assessment tools, such as monitoring and evaluation mechanisms (category 2).

6. Results

6.1. Policy Genealogy and Driving Forces

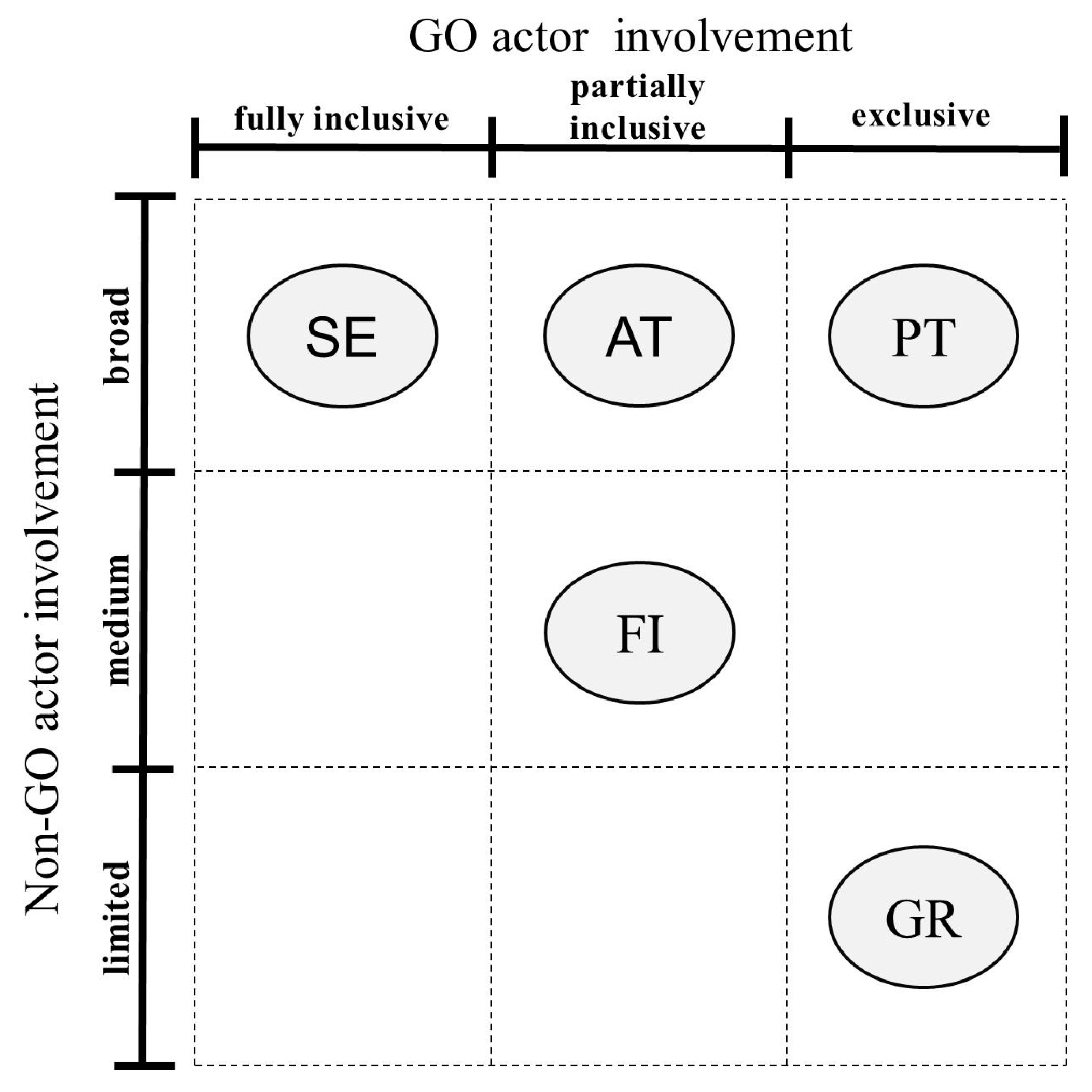

6.2. Inclusive Actor Strategy

6.2.1. Participation of Actors in Strategy Design

6.2.2. Participation of Non-GO Actors in Strategy Implementation

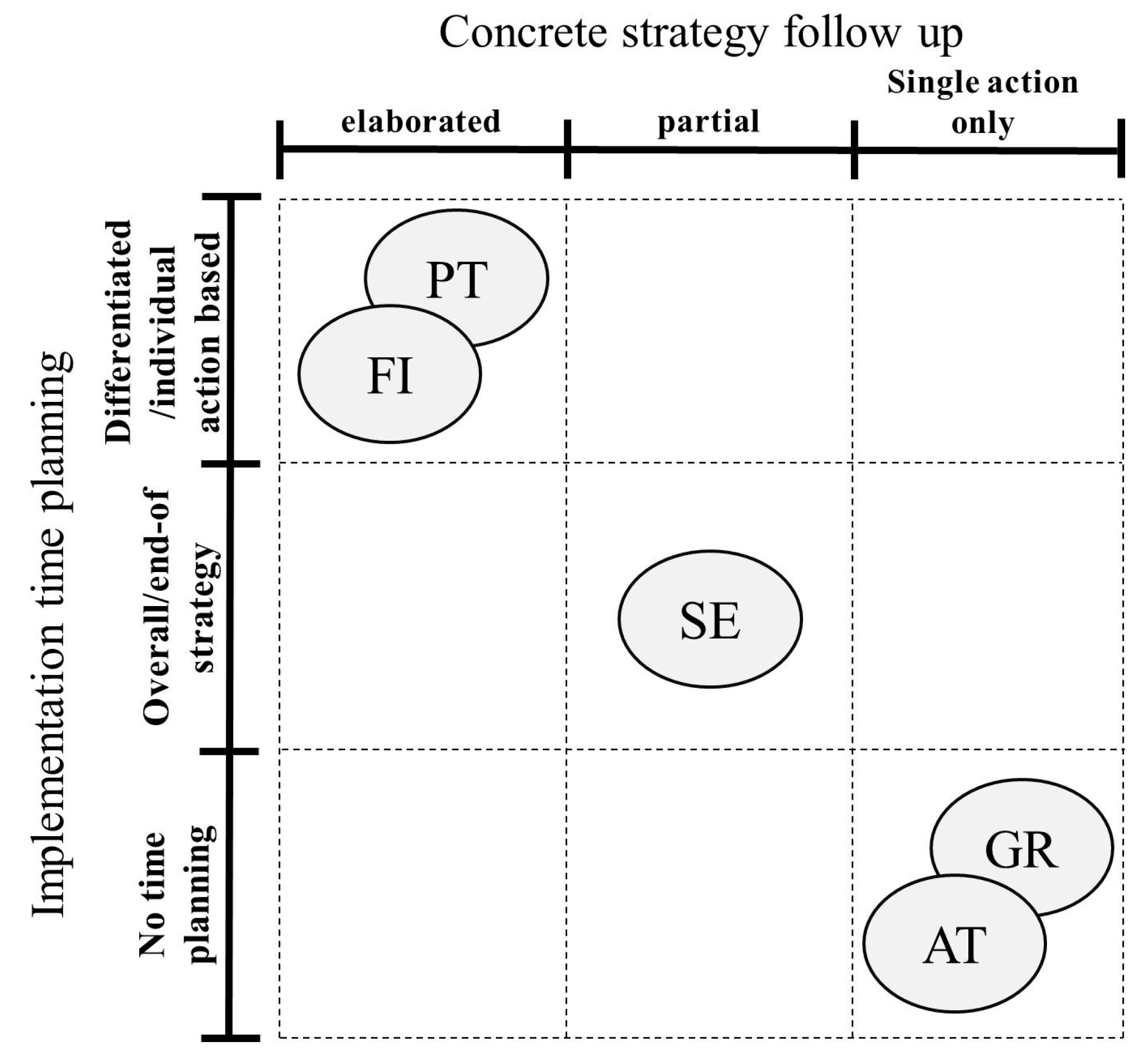

6.3. Strategic Follow-Up Implementation

6.4. Integrated Policy Learning

7. Discussion

- Sustainable mineral supply is characterised by “wicked problem” dynamics, such as different actor interests and capacities (“social pluralism”), organisational fragmentation or silo-thinking (“institutional complexity”). Thus, the more inclusive strategies of Sweden, Austria and, to a lesser extent, Finland and Portugal, support respective “clumsy” solution approaches or, more specifically, more deliberative or participatory policy-making. As also outlined by Everingham et al. [4] (pp. 597–598), these NMS potentially contribute to (i) responsibility sharing; (ii) increased legitimacy for steering; (iii) design and implementation of policy instruments (e.g., land use planning tools or licensing procedures considering civil society interests); or (iv) translating these efforts or attitudes into a local context, where social license to operate is particularly relevant. Creating this arena and culture for participatory decision-making in NMS potentially facilitates trust and cooperation among actors in sustainable mining projects on the ground [5,60,64]. Conversely, in Greece, where, according to Menegaki and Kaliampakos [8] (p. 1437), “reactions against mining remain intense”, efforts on participatory policy-making are marginal compared to other EU MS NMS and, thus, may cause less favourable framework conditions.

- Mining sector challenges, such as mining impacts on ecosystems, or business investment decisions for prospection, have to deal with institutional complexity and unknown long-term dynamics in the future. Thus, a “clumsy” solution approach needs to consider both long-term visioning and short-term action, as well as integrative implementation. In that sense, Finland and Portugal provide a best practice case through a balanced combination of (i) long-term envisioning (i.e., a set of broad objectives), and, at the same time; (ii) strategic design for concrete actions (i.e., policy action plan) that provide clarity for future policy developments [77]. As outlined by Head and Alford [13] (p. 731), flexible framework conditions (degrees of financial and steering freedom for individual action) combined with collaborative leadership (i.e., multi-actor consortia), as applied by Sweden, Finland and Portugal, allow for more adaptive and context-specific implementation.

- The fact that there exists no blueprint for a sustainable extractive sector, and that information needed to take adequate policy decisions is fragmented (“scientific uncertainty”), requires continuously evaluating and adapting current practices. Thus, applying integrated policy learning approaches (e.g., combining qualitative and quantitative evaluation) allows for both reflexivity and learning. Essentially, countries, such as Sweden and, to a lesser extent, Finland, facilitate this flexibility through a comprehensive policy revision process and reduce uncertainty by bringing in collective knowledge from more inclusive policy design and implementation. Contrastingly, Hertin et al. [78] (p. 1185) argue that the actual synergetic relationship is questionable, as, for example, more instrumental and formal policy learning approaches can act as a barrier to open deliberation and the utilization of stakeholder knowledge.

8. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- European Commission. Tackling the Challenges in Commodity Markets and on Raw Materials; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. On the Review of the List of Critical Raw Materials for the EU and the Implementation of the Raw Materials Initiative; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission—DG Growth. Raw Materials, Metals, Minerals and Forest-Based Industries. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/raw-materials/index_en.htm (accessed on 22 June 2017).

- Everingham, J.-A.; Pattenden, C.; Klimenko, V.; Parmenter, J. Regulation of resource-based development: Governance challenges and responses in mining regions of australia. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2013, 31, 585–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Moffat, K. A balancing act: The role of benefits, impacts and confidence in governance in predicting acceptance of mining in Australia. Resour. Policy 2015, 44, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringezu, S.; Potočnik, J.; Schandl, H.; Lu, Y.; Ramaswami, A.; Swilling, M.; Suh, S. Multi-scale governance of sustainable natural resource use—Challenges and opportunities for monitoring and institutional development at the national and global level. Sustainability 2016, 8, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderholm, K.; Söderholm, P.; Helenius, H.; Pettersson, M.; Viklund, R.; Masloboev, V.; Mingaleva, T.; Petrov, V. Environmental regulation and competitiveness in the mining industry: Permitting processes with special focus on Finland, Sweden and Russia. Resour. Policy 2015, 43, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegaki, M.; Kaliampakos, D. Dealing with nimbyism in mining operations. In Mine Planning and Equipment Selection, Proceedings of the 22nd Mpes Conference, Dresden, Germany, 14–19 October 2013; Drebenstedt, C., Singhal, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 1437–1446. [Google Scholar]

- Tiess, G. Towards a european minerals policy. In General and International Mineral Policy: Focus: Europe; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2011; pp. 459–519. [Google Scholar]

- Marinescu, M.; Kriz, A.; Tiess, G. The necessity to elaborate minerals policies exemplified by Romania. Resour. Policy 2013, 38, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, M.L.; Fitzpatrick, P.; Fonseca, A. Unstable shafts and shaky pillars: Institutional capacity and sustainable mineral policy in Canada. Environ. Politics 2014, 23, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, K.; Zhang, A. The paths to social licence to operate: An integrative model explaining community acceptance of mining. Resour. Policy 2014, 39, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, B.W.; Alford, J. Wicked problems: Implications for public policy and management. Adm. Soc. 2015, 47, 711–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. On the Implementation of the Raw Material Initiative; Report of the European Commission, COM(2013) 422 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Enterprise, EAC. Sweden’s Minerals Strategy for Sustainable use of Sweden’s Mineral Resources that Creates Growth throughout the Country; Government Office of Sweden: Stockholm, Sweden, 2012.

- Jordan, A. The governance of sustainable development: Taking stock and looking forwards. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2008, 26, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadowcroft, J. National sustainable development strategies: Features, challenges and reflexivity. Eur. Environ. 2007, 17, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zeijl-Rozema, A.; Cörvers, R.; Kemp, R.; Martens, P. Governance for sustainable development: A framework. Sustain. Dev. 2008, 16, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Material Resources, Productivity and the Environment; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schandl, H.; Fischer-Kowalski, M.; West, J.; Giljum, S.; Dittrich, M.; Eisenmenger, N.; Geschke, A.; Lieber, M.; Wieland, H.; Schaffartzik, A. Global Material Flows and Resource Productivity; Assessment Report for the Unep International Resource Pane; Pre-Publication Final Draft; United Nations Environment Programme: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wellington, T.-A.A.; Mason, T.E. The effects of population growth and advancements in technology on global mineral supply. Resour. Policy 2014, 42, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. The European Environment, State and Outlook 2015; Synthesis Report; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; de Vries, W.; de Wit, C.A. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sievers, H.; Tercero, L. European Dependence on and Concentration Tendencies of the Material Production; Polinares: EU Policy on Natural Resources, Working Paper; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The Raw Materials Initiative, Meeting Our Critical Needs for Growth and Jobs in Europe; Report of the European Commission, COM(2008) 699 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Making raw materials available for europe’s future wellbeing. In Proposal for a European Innovation Partnership on Raw Materials by the European Commission; COM(2012) 82 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Öhrlund, I. Future Metal Demand from Photovoltaic Cells and Wind Turbines: Investigating the Potential Risk of Disabling a Shift to Renewable Energy Systems; STOA—Science and Technology Assessment Report; Science and Technology Options Assessment (STOA): Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Improving Framework Conditions for Extracting Minerals for the EU; Report of the European Commission, Report of the RMSG Ad-Hoc Working Group on Exchanging Best Practices on Land Use Planning, Permitting and Geological Knowledge Sharing; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner, J.; Howlett, M. Introduction: Understanding integrated policy strategies and their evolution. Policy Soc. 2009, 28, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, J.M. A national mineral policy as a regulatory tool. Resour. Policy 1997, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittel, H.W.J.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, D. The era of management is over. Ecosystems 2001, 4, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, S. Jack Beale Memorial Lecture on Global Environment Wicked Problems: Clumsy Solutions—Diagnoses and Prescriptions for Environmental Ills; Institute for Science, Innovation and Society, ANSW: Sydney, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Carley, M.; Christie, I. Managing Sustainable Development, 2nd ed.; Earthscan Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, C.; Cimorelli, A. A demonstration of the necessity and feasibility of using a clumsy decision analytic approach on wicked environmental problems. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2013, 9, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verweij, M.; Douglas, M.; Ellis, R.; Engel, C.; Hendriks, F.; Lohmann, S.; Ney, S.; Rayner, S.; Thompson, M. Clumsy solutions for a complex world: The case of climate change. Public Adm. 2006, 84, 817–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, T. Wicked problems and clumsy solutions: Planning as expectation management. Plan. Theory 2012, 11, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voß, J.-P.; Newig, J.; Kastens, B.; Monstadt, J.; Nölting, B. Steering for sustainable development: A typology of problems and strategies with respect to ambivalence, uncertainty and distributed power. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2007, 9, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, S.; McAllister, M.L. An integrated approach to mineral policy. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2001, 44, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, B.W. Evidence, uncertainty, and wicked problems in climate change decision making in Australia. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2014, 32, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.S.; Neis, B. The rebuilding imperative in fisheries: Clumsy solutions for a wicked problem? Prog. Oceanogr. 2010, 87, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuleman, L.; Niestroy, I. Common but differentiated governance: A metagovernance approach to make the sdgs work. Sustainability 2015, 7, 12295–12321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan-Peter, V.; René, K. Sustainability and Reflexive Government: Introduction; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lafferty, W.M. Introduction: Form and Function in Governance for Sustainable Development; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Meadowcroft, J. Who is in charge here? Governance for sustainable development in a complex world. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2007, 9, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S. In pursuit of sustainable development: A governance perspective. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference of the European Society for Ecological Economics (ESEE), Slovenia, Ljubljana, 29 June–2 July 2009; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, G. Governance for sustainable development: Concepts, principles and challenges. In Eurofound Expert Meeting: Industrial Relations and Sustainability; European Commission: Belgium, Brussels, 2009; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, R.; Parto, S.; Gibson, R.B. Governance for sustainable development: Moving from theory to practice. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 8, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiroyama, H.; Yarime, M.; Matsuo, M.; Schroeder, H.; Scholz, R.; Ulrich, A.E. Governance for sustainability: Knowledge integration and multi-actor dimensions in risk management. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, G.; Steurer, R. Horizontal Policy Integration and Sustainable Development: Conceptual Remarks and Governance Examples; ESDN Office: Vienna, Austria, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Steurer, R. Strategies for sustainable development. In Innovation in Environmental Policy? Integrating the Environment for Sustainability; Jordan, L.A.A., Ed.; Edward Elgar: London, UK, 2008; pp. 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, K. Transparency and Accountability in Science and Politics—The Awareness Principle; Palgrave MacMillan: Bassingstoke, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri, A.; Hjorth, P. Planning for sustainable development: A paradigm shift towards a process-based approach. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 15, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, O.R. Beyond regulation: Innovative strategies for governing large complex systems. Sustainability 2017, 9, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreas Endl, G.B. A Stakeholder Perspective on Sustainable Raw Materials Management; Institute for Managing Sustainability: Vienna, Austria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bridge, G. Contested terrain: Mining and the environment. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2004, 29, 205–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, P.; Fonseca, A.; McAllister, M.L. From the whitehorse mining initiative towards sustainable mining: Lessons learned. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, G.; Basu, A.J. Devising indicators of sustainable development for the mining and minerals industry: An analysis of critical background issues. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2003, 10, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, G.; Murck, B. Sustainable development in the mining industry: Clarifying the corporate perspective. Resour. Policy 2000, 26, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtegha, H.; Cawood, F.; Minnitt, R. National minerals policies and stakeholder participation for broad-based development in the southern African development community (SADC). Resour. Policy 2006, 31, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, L.R.; Dubey, B. Global scenarios of metal mining, environmental repercussions, public policies, and sustainability: A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 43, 2352–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, V.; Miljković, J.; Subić, J.; Jean-Vasile, A.; Adrian, N.; Nicolăescu, E. Sustainable land management in mining areas in Serbia and Romania. Sustainability 2015, 7, 11857–11877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiainen, H. Contemplating governance for social sustainability in mining in greenland. Resour. Policy 2016, 49, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prno, J.; Slocombe, D.S. Exploring the origins of ‘social license to operate’ in the mining sector: Perspectives from governance and sustainability theories. Resour. Policy 2012, 37, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerring, J. Single-outcome studies. Int. Sociol. 2006, 21, 707–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkin, J. The comparative method. In Theory and Methods in Political Science, 3rd ed.; Marsh, G.S.D., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Seawright, J.; Gerring, J. Case selection techniques in case study research: A menu of qualitative and quantitative options. Political Res. Q. 2008, 61, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A.; Strauss, A.L. Basics of Qualitative Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory; Sage Publishing: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. In Basics of Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, I. Grounding Grounded Theory: Guidelines for Qualitative Inquiry; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Leavy, P. The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research; Oxford University Press: Cary, NC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat, Statistical Office of the European Communities. Annual Detailed Enterprise Statistics for Industry (Nace Rev. 2, B-E); Statistical Office of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat, Statistical Office of the European Communities. Material Flow Accounts; Statistical Office of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, T. Survey of Mining Companies; Fraser Institute: Vancouver, BC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dooley, G.; Leddin, A. Perspectives on mineral policy in Ireland. Resour. Policy 2005, 30, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertin, J.; Turnpenny, J.; Jordan, A.; Nilsson, M.; Russel, D.; Nykvist, B. Rationalising the policy mess? Ex ante policy assessment and the utilisation of knowledge in the policy process. Environ. Plan. A 2009, 41, 1185–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, M.; Wortley, L.; Potts, R.; Dedekorkut-Howes, A.; Serrao-Neumann, S.; Davidson, J.; Smith, T.; Nunn, P. Environmental sustainability: A case of policy implementation failure? Sustainability 2017, 9, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadowcroft, J.; Steurer, R. Assessment practices in the policy and politics cycles: A contribution to reflexive governance for sustainable development? J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordbeck, R.; Steurer, R. Multi-sectoral strategies as dead ends of policy integration: Lessons to be learned from sustainable development. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2015, 34, 737–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steurer, R.; Martinuzzi, A. Towards a new pattern of strategy formation in the public sector: First experiences with national strategies for sustainable development in Europe. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2005, 23, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, P.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Sauer, A.; Bornemann, B.; Burger, P. Governing towards sustainability—Conceptualizing modes of governance. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2013, 15, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnouts, R.; van der Zouwen, M.; Arts, B. Analysing governance modes and shifts—Governance arrangements in Dutch nature policy. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 16, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessen, P.P.J.; Dieperink, C.; van Laerhoven, F.; Runhaar, H.A.C.; Vermeulen, W.J.V. Towards a conceptual framework for the study of shifts in modes of environmental governance—Experiences from The Netherlands. Environ. Policy Gov. 2012, 22, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, W.M.; Meadowcroft, J. Introduction. In Implementing Sustainable Development: Strategies and Initiatives in High Consumption Societies; Lafferty, W.M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bulkeley, H.; Jordan, A.; Perkins, R.; Selin, H. Governing sustainability: Rio + 20 and the road beyond. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2013, 31, 958–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Governance for SD Principle | Short Description |

|---|---|

| Integration principle | Policy integration (horizontal) balances economic, social and environmental interests and policies in a way that trade-offs (or negative effects) between them are accounted for or minimised, and synergies (or win-win-win opportunities) are maximised within political institutions [50,51]. |

| Policy integration takes place among multiple levels, or hierarchies, across political-administrative levels (vertical), as well as territorially (i.e., from European to national, down to sub-national political-administrative levels). | |

| Participation | Inclusion of non-governmental stakeholders in public policy-making can have ethical, political (public legitimacy) and knowledge reasons [52]. Quantity versus quality of participation needs to be considered. |

| Long-term visioning and short-term action | Generational impacts and nature of societal transition processes call for the consideration of longer time spans. |

| A process of elaborated planning is needed to translate these long-term oriented visions into practical implementation in the more immediate future. This constitutes a major challenge due to the ambiguity of long-term goals and uncertainty about knowledge and systems development [38,45]. Meadowcroft [45] argued that this could be addressed by developing longer term operational objectives and breaking these down into intermediate ones and measurable targets. | |

| Reflexivity and learning | Unknown dynamics of large scale system transformations, such as the transition towards a sustainable extractive sector call for reflexive processes aimed at “reconsidering existing practices, critically appraising current institutions and exploring alternative futures” [17]. |

| Central to this process is the establishment of effective monitoring and evaluation systems and subsequent “continuous adaptive learning” [53]. Young [54] summarises this approach as a separate governance strategy through the process of goal setting that serves to galvanize the efforts of participants within a specific timeframe and with the benefit of an operational metric for measuring progress. |

| Austria | Sweden | Finland | Portugal | Greece | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic extraction of metal ores in 2016 (tonnes) | 3319.089 | 79,028.485 | 21,972.056 | 11,881.668 | 4572.629 |

| Domestic extraction of metal ores (per cent change 2000–2016) | +45.36% | +65.57% | +558.14% | +14.02% | −4.96% |

| Domestic extraction of non-metallic minerals in 2016 (tonnes) | 108,641.427 | 99,591.772 | 98,433.49 | 101,071.714 | 57,288.256 |

| Domestic extraction non-metallic minerals (per cent change 2000–2016) | −7.96% | +33.09% | −7.54% | −20.44% | +65.27% |

| Jobs in mining and quarrying in 2014 (employed persons) | 6265 | 10,847 | 6318 | 9355 | 6037 |

| jobs in mining and quarrying (per cent change 2008–2014) | −1.23% | +12.14% | +19.16% | −30.32% | +4.39% |

| Policy Perception Index in 2014 (Rank among 122 jurisdictions) | No data available | 4th | 2nd | 40th | 82nd |

| Inclusive Actor Strategy | Strategic Follow up Implementation | Integrated Policy Learning | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Endl, A. Addressing “Wicked Problems” through Governance for Sustainable Development—A Comparative Analysis of National Mineral Policy Approaches in the European Union. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1830. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101830

Endl A. Addressing “Wicked Problems” through Governance for Sustainable Development—A Comparative Analysis of National Mineral Policy Approaches in the European Union. Sustainability. 2017; 9(10):1830. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101830

Chicago/Turabian StyleEndl, Andreas. 2017. "Addressing “Wicked Problems” through Governance for Sustainable Development—A Comparative Analysis of National Mineral Policy Approaches in the European Union" Sustainability 9, no. 10: 1830. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101830

APA StyleEndl, A. (2017). Addressing “Wicked Problems” through Governance for Sustainable Development—A Comparative Analysis of National Mineral Policy Approaches in the European Union. Sustainability, 9(10), 1830. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101830