Livelihood Implications and Perceptions of Large Scale Investment in Natural Resources for Conservation and Carbon Sequestration: Empirical Evidence from REDD+ in Vietnam

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of the Study

1.2. Climate Change and Local Communities in Vietnam: Setting the Scene

1.3. Aim and Outline of the Study

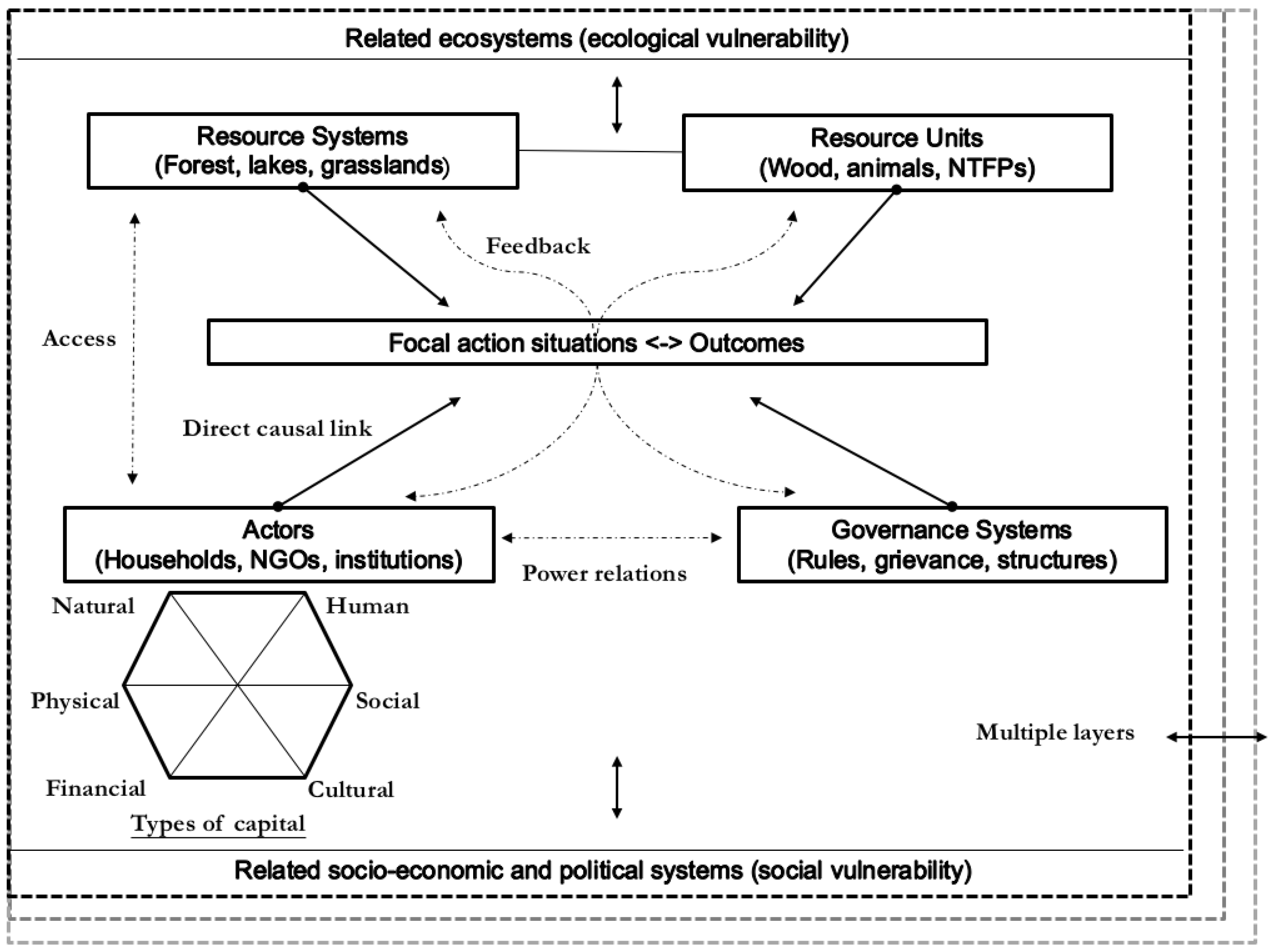

2. Theoretical Framework: Assessing Livelihood Implications and Perceptions

3. Research Context and Methods

3.1. Forest Governance and REDD+ in Vietnam

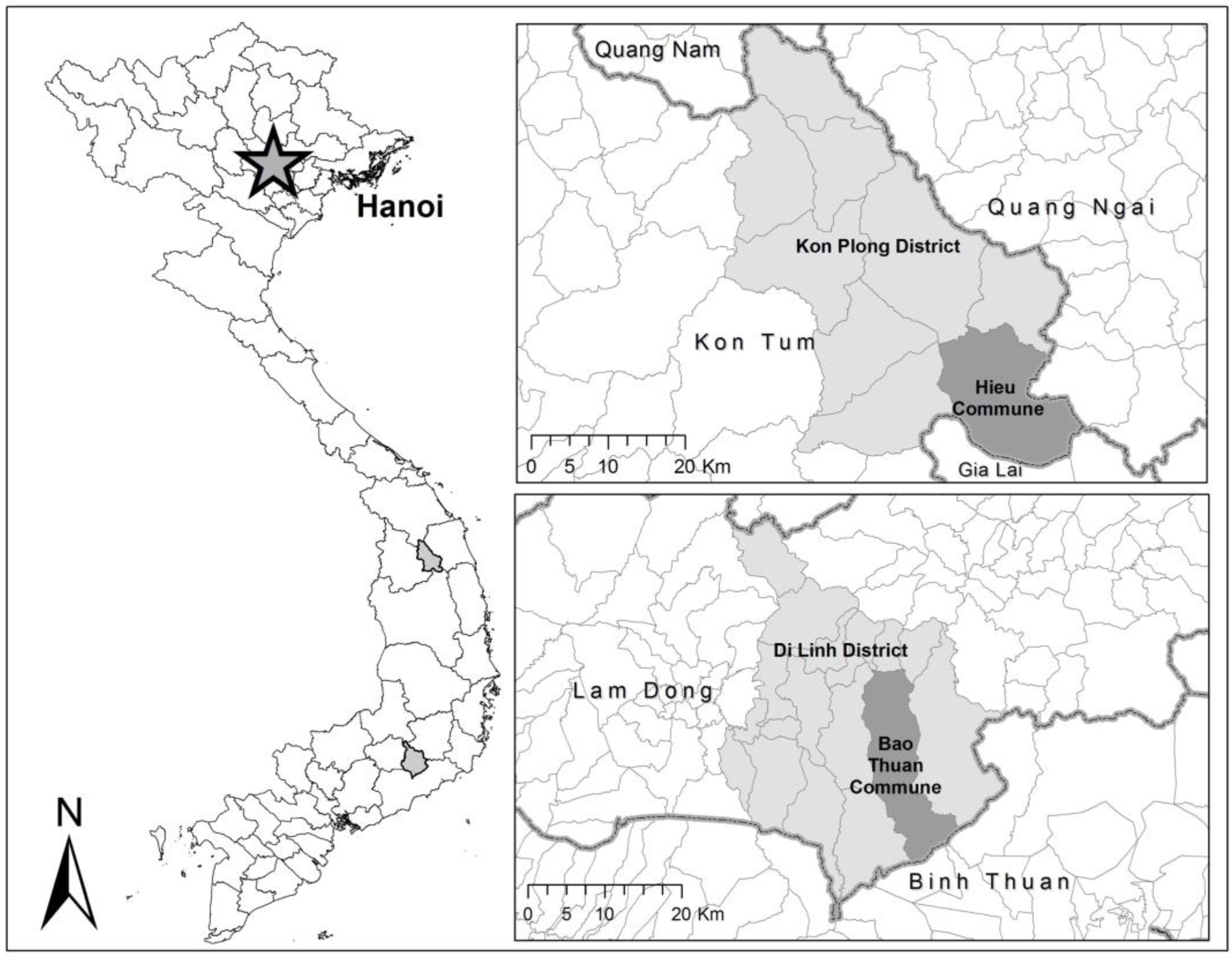

3.2. Selection Criteria for the Research Sites

3.3. Methodology and Operationalisation

3.4. Research Context

4. Results

4.1. Drivers of Change: REDD+

4.2. Livelihood Strategies and Capabilities

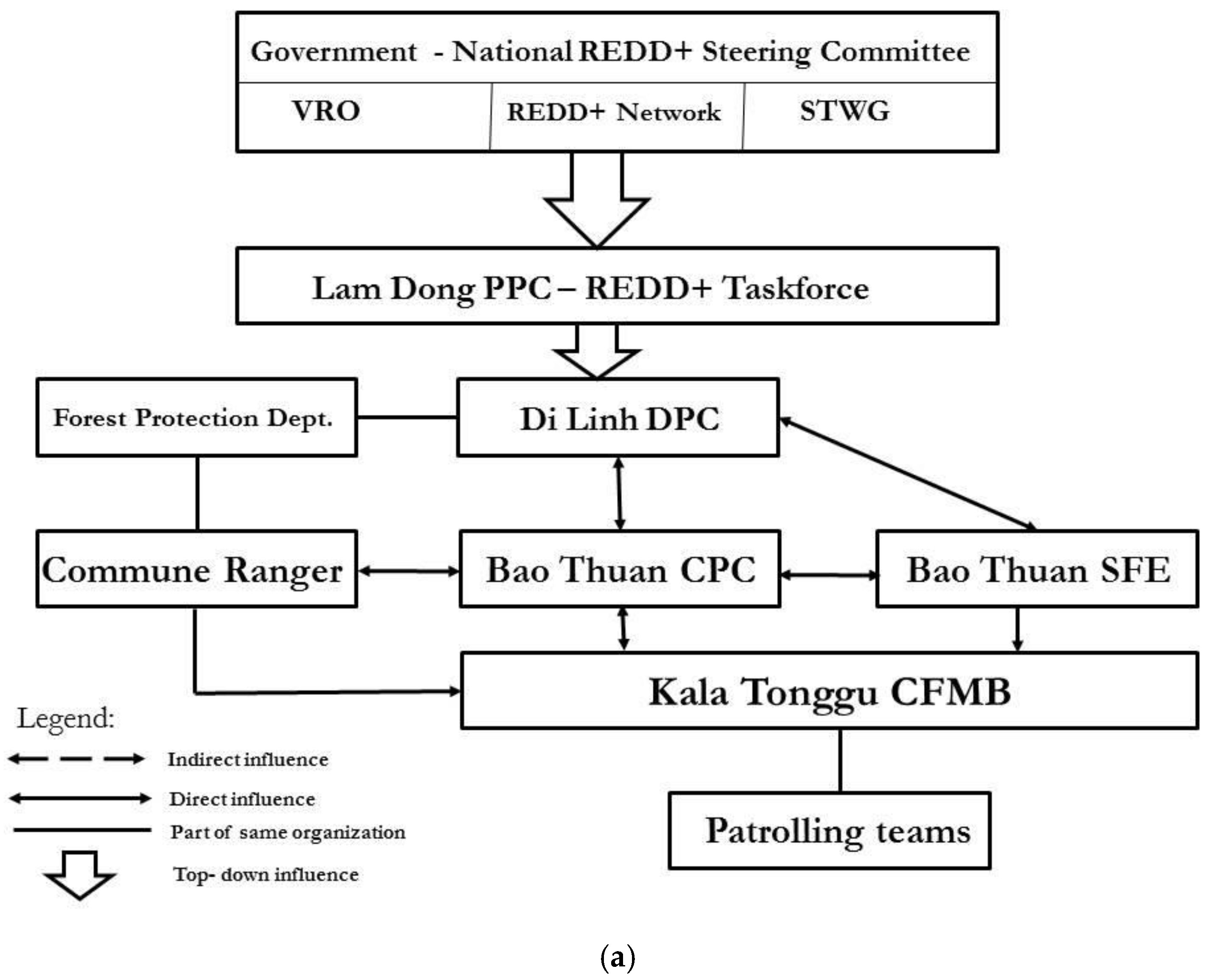

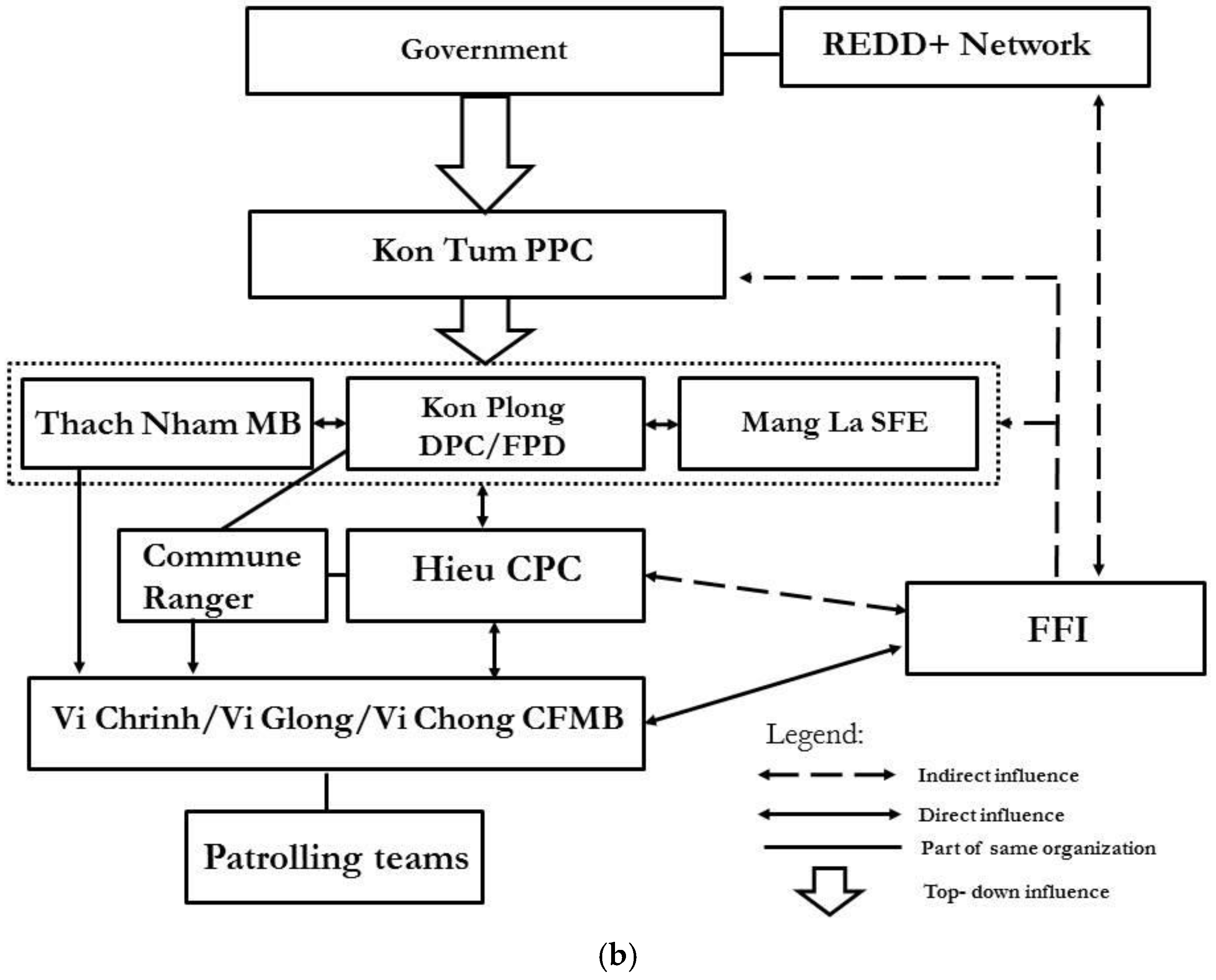

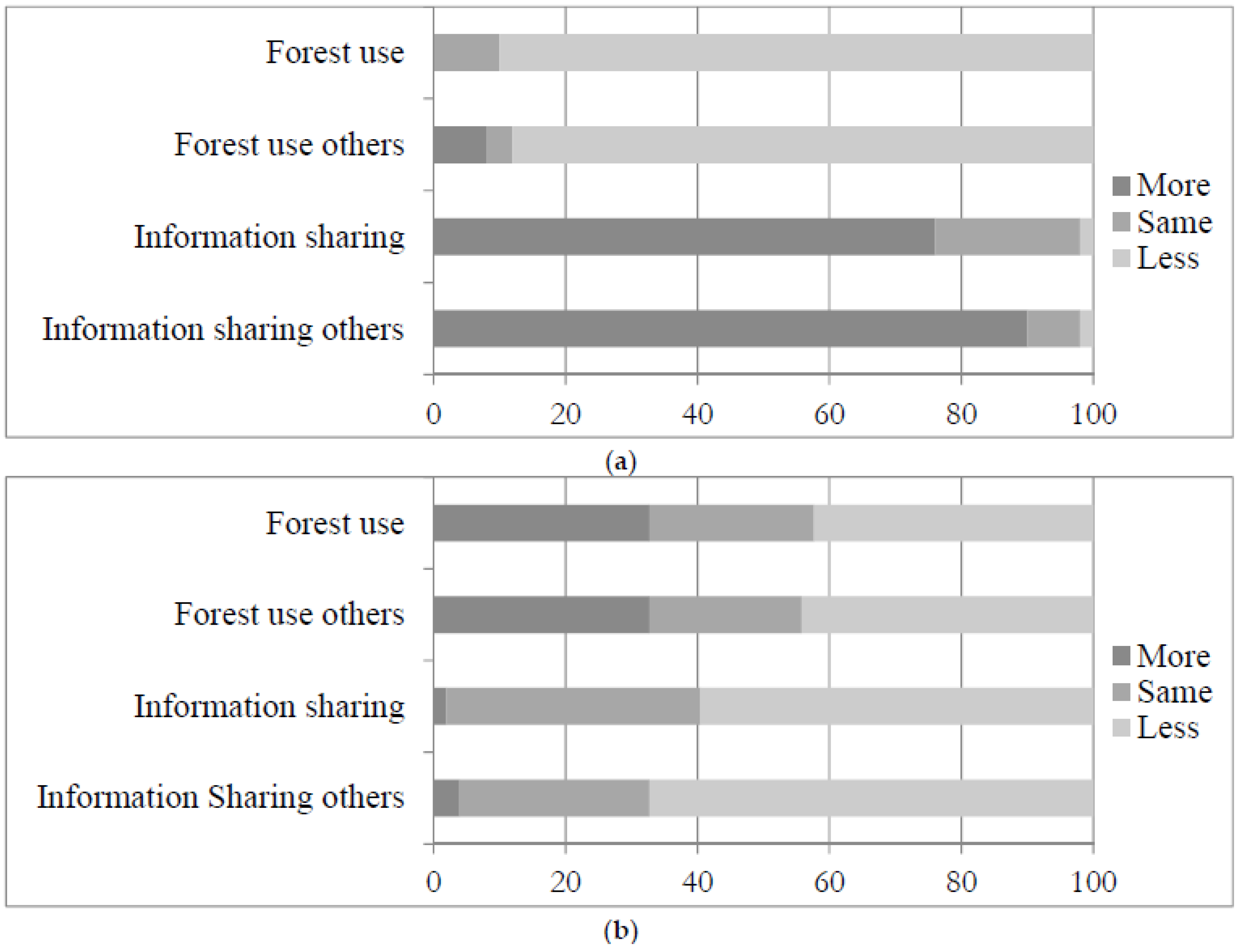

4.3. Governance Systems and Actors

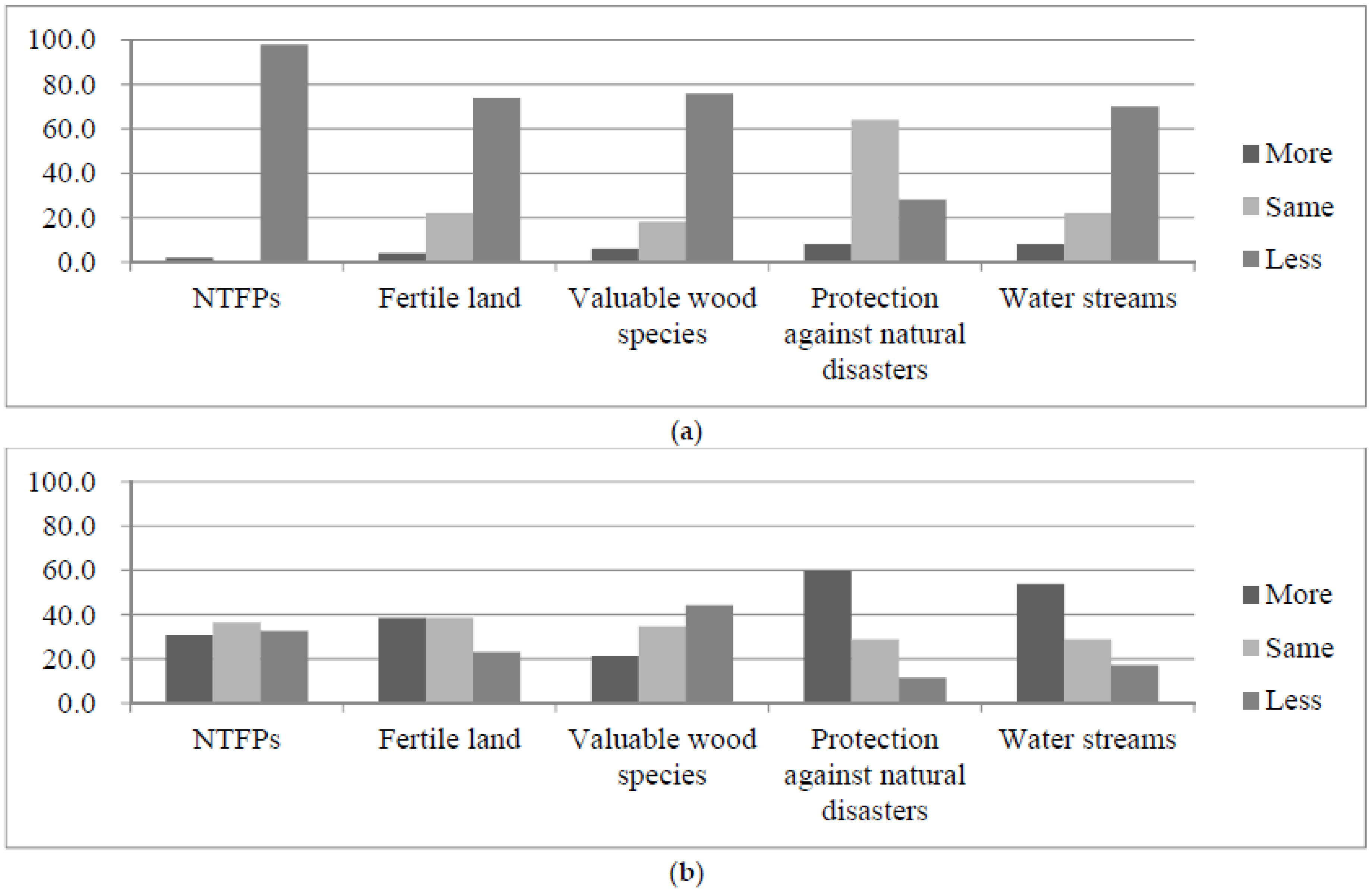

4.4. Resource Systems and Units

4.5. Focal Action Situations and Outcomes

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Concluding Remarks and Contribution to the Literature

5.2. Policy Recommendations

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Steffen, W.; Grinevald, J.; Crutzen, P.; McNeill, J. The anthropocene: Conceptual and historical perspectives. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2011, 369, 842–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 13. Available online: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/climate-change-2/ (accessed on 5 August 2017).

- Rahlao, S.; Mantlana, B.; Winkler, H.; Knowles, T. South Africa’s national REDD+ initiative: Assessing the potential of the forestry sector on climate change mitigation. Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 17, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, M.H.; Do, T.H.; Pham, M.T.; van Noordwijk, M.; Minang, P.A. Benefit distribution across scales to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in Vietnam. Land Use Policy 2013, 31, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, J.I.; Dauvergne, P. The Global south in environmental Negotiations: The politics of coalitions in REDD+. Third World Q. 2013, 34, 1307–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, O.P.; Hendriks, A.; Rand, D.G.; Nowak, M.A. Think global, act local: Preserving the global commons. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoomers, A.; Otsuki, K. Addressing the impacts of large-scale land investments: Re-engaging with livelihood research. Geoforum 2017, 83, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrak, M.M.; Marafa, L.M. Ten years of REDD+: A critical review of the impact of REDD+ on forest-dependent communities. Sustainability 2016, 8, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Corbera, E.; Hunsberger, C.; Vaddhanaphuti, C. Climate change policies, land grabbing and conflict: perspectives from Southeast Asia. Rev. Can. Etudes Dev. 2017, 38, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heynen, N.; McCarthy, J.; Prudham, W.S.; Robbins, P. Neoliberal Environments: False Promises and Unnatural Consequences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zoomers, A.; Van Westen, G.; Terlouw, K. Looking forward: Translocal development in practice. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2011, 33, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoomers, A.; Van Westen, G. Introduction: Translocal development, development corridors and development chains. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2011, 33, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairhead, J.; Leach, M.; Scoones, I. Green grabbing: A new appropriation of nature? J. Peasant Stud. 2012, 39, 237–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoomers, A.; van Noorloos, F.; Otsuki, K.; Steel, G.; Van Westen, G. The Rush for land in an urbanizing world: From land grabbing toward developing safe, resilient, and sustainable cities and landscapes. World Dev. 2017, 92, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Thome, P.; Nguyen, T.H.; Pham, T.L.; Jarva, J.; Nuottimäki, K. Climate change in Vietnam. In Climate Change Adaptation Measures in Vietnam; Springer: Medford, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- CIA World Factbook. Country Profile: Vietnam. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/vm.html (accessed on 10 September 2017).

- Asian Development Bank. Indigenous Peoples/Ethnic Minorities and Poverty Reduction in Vietnam; Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- De Haan, L.J. The livelihood approach: A critical exploration. Erdkunde 2012, 66, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, L.J.; Zoomers, A. Exploring the frontier of livelihoods research. Dev. Chang. 2005, 36, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Commodities and Capabilities; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R.; Conway, G.R. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century; Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex: Brighton, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R. Poverty and livelihoods: Whose reality counts? Environ. Urban. 1995, 7, 173–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, D. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: What Contribution Can We Make; Department for International Development: London, UK, 1998.

- Scoones, I. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis; Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex: Brighton, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, F. Household strategies and rural livelihood diversification. J. Dev. Stud. 1998, 35, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, A. Social capital and development. In The Companion to Development Studies; Hoddor: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- De Haan, L.J.; Zoomers, A. Development geography at the crossroads of livelihood and globalisation. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2003, 94, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakdapolrak, P. Livelihoods as social practices–re-energising livelihoods research with Bourdieu’s theory of practice. Geogr. Helv. 2014, 69, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, L.J. Livelihoods in development. Rev. Can. Etudes Dev. 2016, 38, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.; Mearns, R.; Scoones, I. Environmental entitlements: Dynamics and institutions in community-based natural resource management. World Dev. 1999, 27, 225–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. From community-based resource management to complex systems: The scale issue and marine commons. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Gibson, C.C. (Eds.) Communities and the Environment: Ethnicity, Gender, and the State in Community-Based Conservation; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- De Bruijn, M.; van Dijk, H. Climate and society in Central and South Mali. In Sahelian Pathways. Climate and Society in Central and South Mali, 1st ed.; De Bruijn, M., van Dijk, H., Kaag, M., van Til, K., Eds.; African Studies Center: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Holling, C.S.; Berkes, F.; Folke, C. Science, sustainability and resource management. In Linking Social and Ecological Systems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. A diagnostic approach for going beyond panaceas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15181–15187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGinnis, M.D. Building a Program for Institutional Analysis of Social-Ecological Systems: A Review of Revisions of the SES Framework; Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E.; Cox, M. Moving beyond panaceas: A multi-tiered diagnostic approach for social-ecological analysis. Environ. Conserv. 2010, 37, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallopín, G.C. Linkages between vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A General framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderies, J.M.; Janssen, M.A.; Ostrom, E. A framework to analyse the robustness of social-ecological systems from an institutional perspective. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, P.; Dressler, W.; Mahanty, S. REDD+ for Red Books? Negotiating rights to land and livelihoods through carbon governance in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. Geoforum 2017, 81, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElwee, P.D. Payments for environmental services as neoliberal market-based forest conservation in Vietnam: Panacea or problem? Geoforum 2012, 43, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikor, T.; Nguyen, T.Q. Why may forest devolution not benefit the rural poor? Forest entitlements in Vietnam’s central highlands. World Dev. 2007, 35, 2010–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castella, J.C.; Boissau, S.; Thanh, N.H.; Novosad, P. Impact of forestland allocation on land use in a mountainous province of Vietnam. Land Use Policy 2006, 23, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, B.V.; Catacutan, D.C.; Ha, H.M. Importance of national policy and local interpretation in designing payment for forest environmental services scheme for the Ta Leng River Basin in Northeast Vietnam. Environ. Natl. Res. Res. 2014, 4, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.L.; Trinh, N.T. Description of Communities Participating in the EU-REDD+ Project in Kon Plong District, Kon Tum Province, Vietnam, Technical Report No. 1; Fauna and Flora International: Kon Tum, Vietnam, 2012; unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Forwet. Survey Report on Forest Contracts to Da Sar Commune and Forestland Allocation to Communities in Bao Thuan and Phu Hoi Communes, Lam Dong Province; Research Center for Forests and Wetlands: Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation on Organisation, Management, Activities and Benefit Sharing in the Community Forest of Kala Tonggu Village, Bao Thuan Commune; Commune People’s Committee (CPC) of Bao Thuan: Di Linh, Vietnam, 2012; unpublished.

- Dang, T.L. Personal Communication; Fauna and Flora International: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fauna and Flora International (FFI). Policy Bulletin No. 3–REDD+ Pilot Project: Key Lessons Learned for Expanding the National REDD+ Model and Its Implementation; FFI: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- The United Nations Collaborative Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (UN-REDD). Manual for Interlocutors: To Conduct FPIC Village Consultation Meetings; UN-REDD: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2012; Available online: http://www.unredd.net/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_details&gid=7674&Itemid=53 (accessed on 5 August 2017).

- The United Nations Collaborative Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (UN-REDD). UN-REDD Viet Nam Phase II Programme: Operationalising REDD+ in Viet Nam; UN-REDD: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP); Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Personal Communication; UNDP & FAO: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- The Center for People and Forests (RECOFTC). Evaluation and Verification of the Free, Prior and Informed Consent Process under the UN-REDD Programme in Lam Dong Province, Vietnam; RECOFTC: Bangkok, Thailand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Salemink, O. The Ethnography of Vietnam’s Central Highlanders: A Historical Contextualization 1850–1990; RoutledgeCurzon: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, G.C. The Highland People of South Vietnam: Social and Economic Development, 1st ed.; Rand Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Traedal, L.T.; Vedeld, P.O.; Pétursson, J.G. Analyzing the transformations of forest PES in Vietnam: Implications for REDD+. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 62, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrak, M.M.; Marafa, L.M. The role of sacred forests and traditional livelihoods in REDD+: Two case studies in Vietnam’s Central Highlands. In Shifting Cultivation Policies: Balancing Environmental and Social Sustainability, 1st ed.; Cairns, M., Ed.; Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International (CABI): Wallingford, UK, 2017; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Maraseni, T.N.; Neupane, P.R.; Lopez-Casero, F.; Cadman, T. An assessment of the impacts of the REDD+ pilot project on community forests user groups and their community forests in Nepal. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 136, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, A. Diversification by Smallholder Farmers: Viet Nam Robusta Coffee. Agricultural Management, Marketing and Finance Working Document; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cerbu, G.A.; Sonwa, D.J.; Pokorny, B. Opportunities for and capacity barriers to the implementation of REDD+ projects with smallholder farmers: Case study of Awae and Akok, Centre and South Regions, Cameroon. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 36, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, E.; Linnerad, K.; Banister, D. The Imperatives of sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 25, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Site: | Kala Tonggu (n = 50) | Hieu (n = 52) |

|---|---|---|

| Dimension: | ||

| REDD+ project | Multilateral (UN-REDD) | NGO (FFI-REDD+) |

| Demographics |

|

|

| Poverty rate | 12.5% (2013) | 75% (2012) |

| Forestland | Natural forestland: 537 ha. | Natural forestland: 18,984 ha of which 2988 ha was degraded (2014). |

| Existing forest management structure | Kala Tonggu was involved in PFES, CBFM (500 ha, Red Book since 2011) and forest patrolling (Green Books). | Only Vi Chrinh village owned a community Red Book (808 ha, since 2008), some other villagers had Green Books. |

| Ethnicity | K’ho people formed the majority. | M’nam people formed the majority. |

| General livelihood strategy | Mainly coffee smallholders. | Mainly swidden agriculturalists. |

| Connectivity | Relatively well connected to Dalat City. Located besides a provincial road and Dong Nai River | Relatively isolated. Three-hour drive to Kon Tum town–the provincial capital. |

| Research Site: | Kala Tonggu | Hieu |

|---|---|---|

| Dimension: | ||

| Time period | Pilot site of UN-REDD since 2010 (78 villages in Lam Dong province were targeted). | FFI-REDD+ started in 2011 and lasted until 2014 in the commune. |

| Targeted forest area | 537 ha in the village (Forest targeted for protection and reforestation covered 8954.98 ha in entire Bao Thuan commune). | 18,984 ha. |

| REDD+ activities and funding |

|

|

| Focus and approach | Clear focus on carbon sequestration and community carbon monitoring. A do-no-harm approach. | Resembled more an Integrated Conservation and Development Project. Carbon sequestration was one of the many development goals of this project. |

| REDD+ promotional video | https://goo.gl/AjwA3e | https://goo.gl/pUdN4t |

| Kala Tonggu | Per Cent | No Land or Red Book | Government Policy | Lack of Skills and Knowledge | No Time | Personal Choice | No/Other Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swidden agriculture | 100 | - | - | - | - | - | 100 |

| Intensive cultivation | 100 | 26.0 | - | 16.0 | 26.0 | 30.0 | 2.0 |

| Logging for housing | 100 | - | 50.0 | - | - | 26.0 | 24.0 |

| Logging for selling | 100 | - | 66.0 | - | - | 28.0 | 6.0 |

| Coffee plantations | 2.0 | - | - | - | - | - | 100 |

| Collecting NTFPs | 50.0 | - | 76.0 | - | - | 24.0 | - |

| Hunting and catching animals | 100 | - | 44.0 | - | - | 44.0 | 12.0 |

| Hieu | |||||||

| Swidden agriculture | 26.9 | 50.0 | - | - | - | - | 50.0 |

| Intensive cultivation | 88.5 | 32.6 | - | 34.8 | - | - | 32.6 |

| Logging for housing | 34.6 | - | 83.3 | - | - | - | 16.7 |

| Logging for selling | 100 | - | 100 | - | - | - | - |

| Coffee plantations | 88.5 | 52.1 | 10.9 | - | 10.9 | 10.9 | 15.2 |

| Collecting NTFPs | 42.3 | - | 59.1 | - | 36.4 | 4.5 | |

| Hunting and catching animals | 86.5 | - | 60.0 | - | 26.7 | 11.1 | 2.2 |

| Forest Classification | Kala Tonggu | Hieu | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strictly formal | Protection forest | Estimated size | 500 | 204 |

| Location | 56.0 | 51.0 | ||

| Boundary | 48.0 | 39.2 | ||

| Special-use forest | Estimated size | ? | ? | |

| Location | 4.0 | 25.5 | ||

| Boundary | 4.0 | 17.6 | ||

| Formal and customary | Community forest | Estimated size | 484.4 | 1524.8 |

| Location | 64.0 | 78.4 | ||

| Boundary | 58.0 | 58.8 | ||

| Shifting cultivation forest (individual plot) | Estimated size | 0.5 | 5.9 | |

| Location | 98.0 | 88.2 | ||

| Boundary | 98.0 | 76.5 | ||

| Customary | Watershed protection forest | Estimated size | ? | ? |

| Location | 8.0 | 35.3 | ||

| Boundary | 8.0 | 17.6 | ||

| Ghost forest | Estimated size | - | 15.8 | |

| Location | - | 88.2 | ||

| Boundary | - | 74.5 | ||

| Key Dimension: | Policy Steps and Key Questions |

|---|---|

| Formal and customary forest boundaries and systems | How does REDD+ restructure local and indigenous landscapes?

|

| Formal and customary institutions | How does REDD+ restructure the existing forest governance infrastructure in a community?

|

| Temporal dynamics of livelihoods | What kind of livelihood alternatives does REDD+ provide and can REDD+ cope with the temporal dynamics of community livelihoods?

|

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bayrak, M.M.; Marafa, L.M. Livelihood Implications and Perceptions of Large Scale Investment in Natural Resources for Conservation and Carbon Sequestration: Empirical Evidence from REDD+ in Vietnam. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101802

Bayrak MM, Marafa LM. Livelihood Implications and Perceptions of Large Scale Investment in Natural Resources for Conservation and Carbon Sequestration: Empirical Evidence from REDD+ in Vietnam. Sustainability. 2017; 9(10):1802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101802

Chicago/Turabian StyleBayrak, Mucahid Mustafa, and Lawal Mohammed Marafa. 2017. "Livelihood Implications and Perceptions of Large Scale Investment in Natural Resources for Conservation and Carbon Sequestration: Empirical Evidence from REDD+ in Vietnam" Sustainability 9, no. 10: 1802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101802

APA StyleBayrak, M. M., & Marafa, L. M. (2017). Livelihood Implications and Perceptions of Large Scale Investment in Natural Resources for Conservation and Carbon Sequestration: Empirical Evidence from REDD+ in Vietnam. Sustainability, 9(10), 1802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101802