1. Introduction

It has been widely acknowledged that residents’ attitudes are important for the sustainability of tourism developments because they live in proximity to the resources and often have grown to be dependent upon them [

1]. They stand to gain or lose from their involvement in such developments, both as individuals and communities, depending upon their ability to continue to use their existing livelihood strategies and adopt new ones based upon novel tourism opportunities. Findings are contingent, reflecting the attributes of communities and the options that are available to them. Thus, generalization is difficult and this is a strong reason to advocate for public involvement in situations where local lives may be impacted. One way of seeking their input is through undertaking resident surveys.

The creation of parks and protected areas, including World Heritage Sites, provides both challenges and opportunities for residents living in and around the sites. Often they experience dislocations in their use of resources and sometimes they are removed from the protected area in an effort to protect it by reducing pressures on natural resources [

2,

3,

4]. Thus, the well-being of residents is of growing concern in situations of protected area designation.

The situation that is addressed in this paper is particularly challenging because it involves a previously mobile group of people that have been required to become sedentary as part of a World Heritage designation strategy. Pastoralists, who formerly roamed across the grasslands with their animals, have been re-settled in new communities where the raising of animals is more difficult but the provision of social services, such as medical care and education, is easier. It is expected that their former pastoral livelihood will be replaced by the provision of tourism services. It is important to understand how they interpret these major changes in their lifestyles and livelihoods.

Accordingly, the present study takes the Bogda World Natural Heritage area in northwestern China as a case study, with the objective of assessing local residents’ attitudes and perceptions towards participation in heritage conservation, and to research the means by which to promote positive attitudes and participation. In order to address these topics, a questionnaire survey with local residents was conducted and the results are reported below. Their implications for heritage conservation and the well-being of informants are discussed. The results of the empirical study can be provided to policy makers and managers for use in the sustainable conservation of the grasslands. The study contributes to the literature on community participation at natural heritage sites through exploration of the experiences of a previously nomadic group of pastoralists.

2. Literature Review

Community-based natural resources management and biodiversity conservation have been applied in many parts of the world [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Some previous related studies have focused on community involvement and relationships between a protected area and the community, and it has been concluded that participatory approaches and collaboration can promote positive relationships between management agencies and local people, thereby supporting protection of the reserve [

9,

10,

11]. Moreover, several studies have shown that local attitudes are a key factor that influences relationships between communities and protected areas [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. From a review of 105 published documents focusing on wildlife conservation, community involvement and protected area–community relationships, it emerged that relationships are mostly influenced by attitudes [

18]. Therefore, the assessment of peoples’ attitudes towards conservation and perceptions of management activities have become important inputs into conservation. Community attitudes towards conservation are affected by some factors, including household size, sources of income, education level and age [

19,

20], human-wildlife benefits [

21], and where livestock are important source of sustenance, size of the herd [

22].

It is important to research the means by which positive attitudes and the willingness of communities to participate in conservation can be fostered. The perceptions of local people towards conservation policies and related management interventions, as well as possible options for conflict resolution, were analyzed for the Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, a World Heritage Site in the Indian Himalayas [

23]. This study indicated that if the development interests of the local people are marginalized for a long period of time, they may adopt actions which are detrimental to the goal of protection. The complexities of community participation in natural resource management, ranging from interrelations among stakeholders to resource ownership, have been explored in the Kasanka Game Management Area, Zambia [

24]. Elsewhere, in Mexico, levels of local participation have been compared across protection schemes, particularly regarding payment-based and community-initiated strategies, revealing that community-based conservation areas, even when providing economic benefits to local people, do not always facilitate wider involvement of community members in conservation [

25]. One of the key success factors for sustainable conservation is the level of awareness of the heritage value of the resources by the stakeholders, particularly local people [

26].

3. Methodology

The case study methodology that is employed will be discussed under two parts. First the study area will be described and its selection will be justified. Then, the methods of data acquisition will be presented.

3.1. Study Area

Bogda World Natural Heritage is located in the central part of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, China, in the eastern part of the Tianshan Mountains (

Figure 1). Its central geographic coordinates are 43°50′00″ N, 88°17′12″ E, with the core area covering 38,739 ha and the peripheral buffer zone area covering 41,547 ha (

Figure 1). The main conservation features at Bogda include the mountainous natural landscapes, the mountain forest ecosystem, rare and endangered wild animals and their habitats, as well as the rich presence of glaciers, rivers and lakes.

Bogda mountain ecosystem plays a very important role in soil and water conservation, and in water resource protection, among the environmental services that it provides. Guided by estimations of the carrying capacity, in order to alleviate grazing conflicts and to restore the grassland environment, as well as to maintain the sustainable development of the mountain ecosystem, a policy of settlement of pastoralists and grazing restrictions was first implemented in the Bogda region in 2005. The complete prohibition of grazing in the core zone at the heritage site was implemented by 2012.

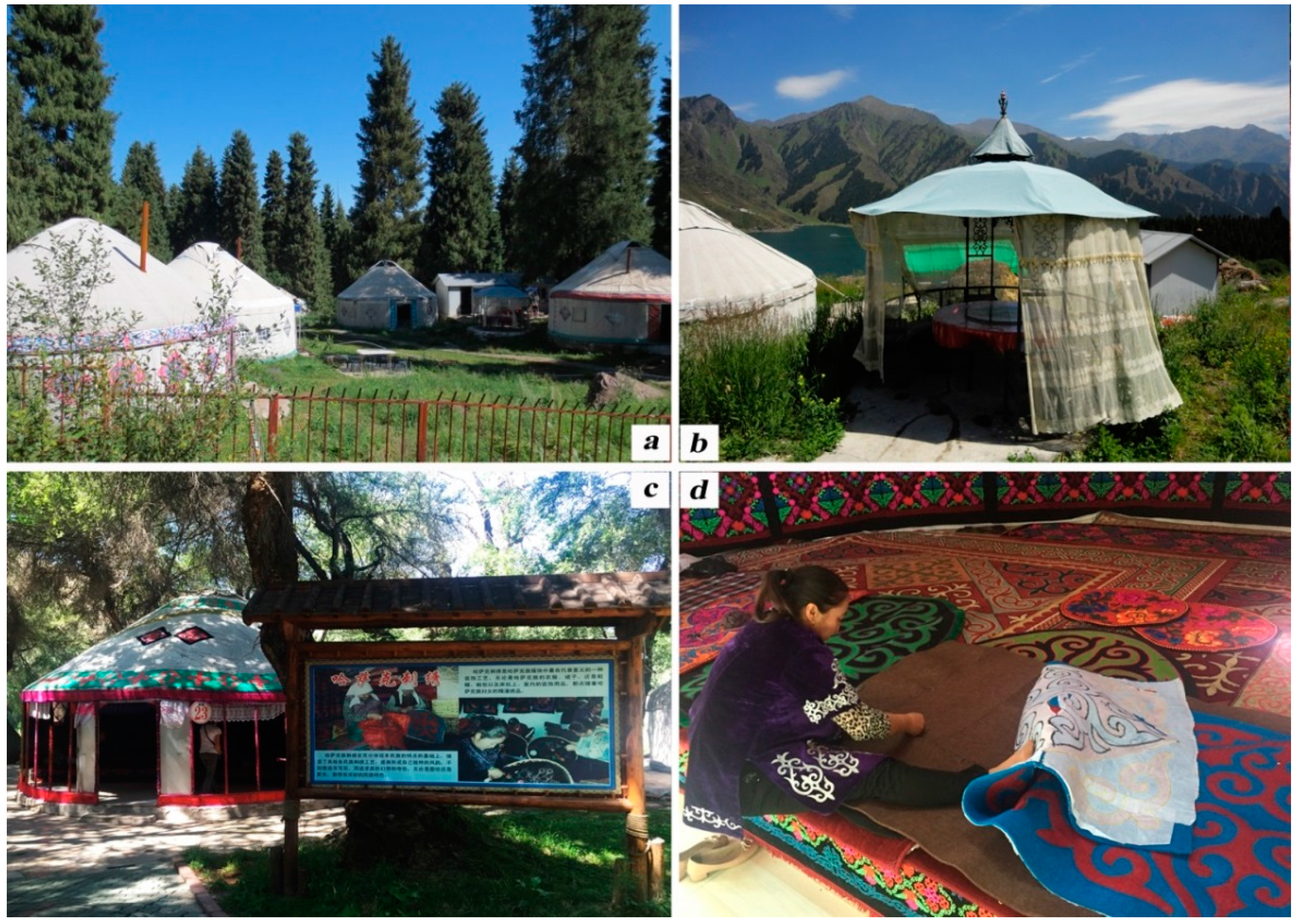

Since the implementation of the grazing ban at the Bogda heritage site, the livelihoods of the pastoralists have changed, shifting from nomadism to engagement in tourism. The formerly nomadic people were settled in two sedentary communities, the Bogda Kazakh ethnic community and the Kuokehula Kazakh ethnic community, which in the buffer zone of Bogda heritage site (

Figure 2). Local people of the two communities main operations are song and dance performances, managing the displays at arts and crafts events, sales of souvenirs and characteristic ethnic foods and beverages.

3.2. Survey

A preliminary field survey of residents’ perceptions was first conducted by the authors during the period of 28 to 31 July 2015. The pre-survey was directed at the local community of the Bogda heritage site. It was aimed at verifying whether the questionnaire was logical and goal-oriented.

After the pre-survey, a formal household questionnaire survey was undertaken during the period of 8 to 22 August 2015. The questionnaire was administered by the authors, and supplemented by face-to-face interviews, thereby improving the quality of the answers as well as the response rate.

The questionnaire is divided into three parts: the first part mainly involves the demographic questions of respondents, including gender, age, education, family composition, household income and income sources, and so on; the second part investigates the attitudes and perceptions of the community residents to the values of the Bogda heritage site, and participation in heritage conservation; and the third part investigates the factors affecting the community residents’ willingness to participate in heritage conservation, means of participation and compensation.

There were a total of 159 households in the residential communities in the buffer areas of the Bogda heritage site in 2015. The authors approached a household and asked whether he/she was available and willing to answer the survey. If a resident did not cooperate, the author thanked him or her and approached the next household. If a respondent was willing to answer the survey, a questionnaire sheet was given to him/her to complete. Most of the Kazakh residents were able to communicate and were able to complete the questionnaire. Where language barriers existed, Kazakh college students who had received Chinese language education assisted with translation.

A total number of 120 household questionnaires were collected, of which 106 valid questionnaires were completed, constituting an effective rate of 88%. Fourteen invalid questionnaires were excluded from the analysis owing to inconsistent or incomplete responses. This sample size was appropriate to assess the attitudes and perceptions of local residents towards their participation in the protection of the heritage site.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Sample Characteristics

Men (61%) were more willing to accept the survey and express views than women, reflecting the fact that they are the main voice of the family (

Table 1). More than half (56%) of the interviewees are aged between 36 and 50. Such people are important pillars of their families, earning an income and taking on family responsibilities, such as educating children and supporting the elderly. Kazakh families attach great importance to the education of their children and almost all of the interviewees had received junior high school (43%) or high school (46%) education. Most (65%) of the respondents’ families had either four or five members. Almost half (47%) of the households have an annual income below CNY 30,000 (US $4625). The main source of household income is the provision of tourist reception service.

4.2. Perceptions of the World Natural Heritage

During the Bogda World Natural Heritage nomination process, the administrators carried out numerous publicity activities among the residents for heritage conservation. Therefore, more than half (55%) of the respondents claim to understand that World Natural Heritage must be strictly protected (

Figure 3), and 15% of the respondents are aware that World Natural Heritage status is a kind of honor and brand, and this makes them proud of where they live. However, approaching a third (30%) of respondents lack a clear understanding of what World Natural Heritage really means.

Questions: What are your perceptions about World Natural Heritage?

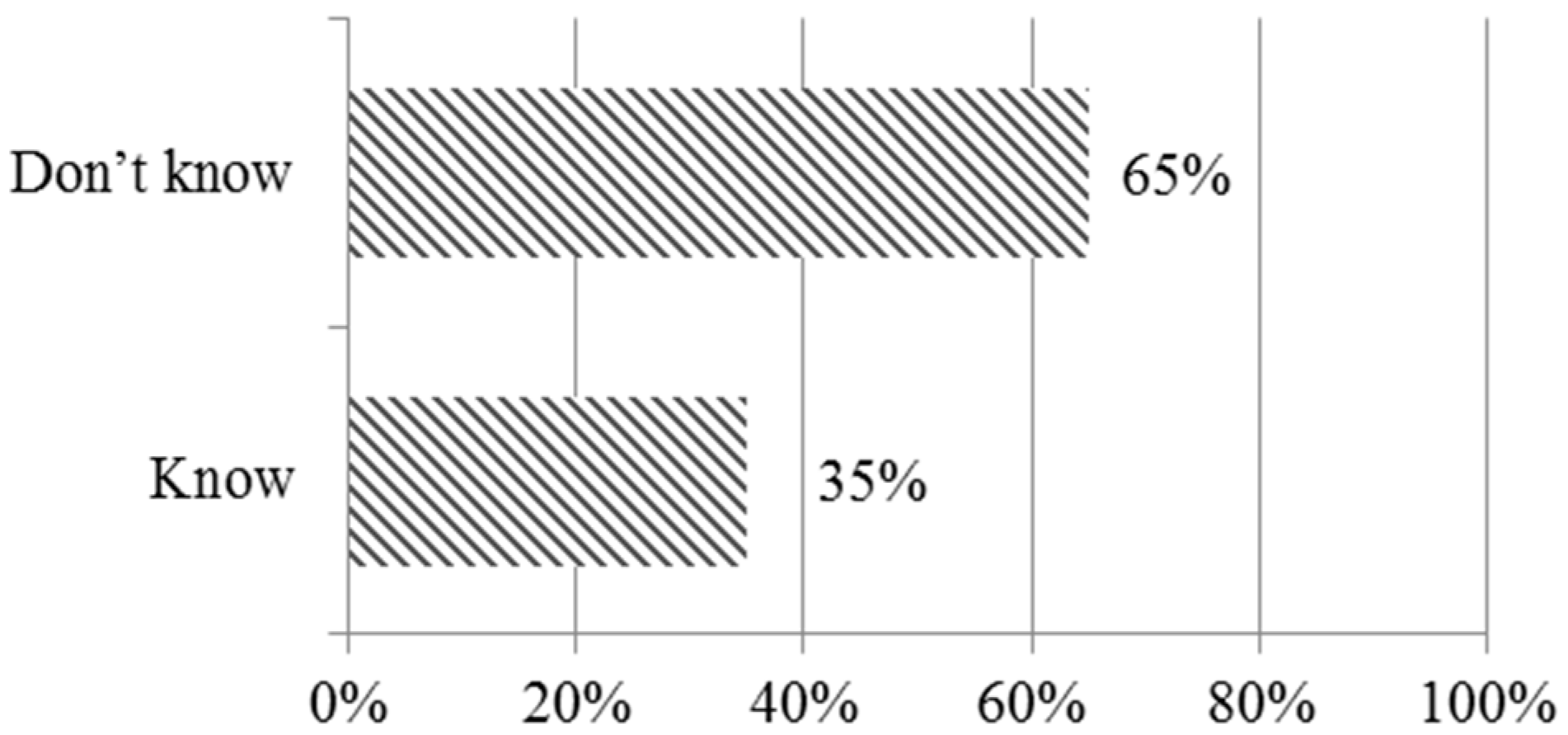

Most (65%) of the respondents do not understand the notion of “outstanding universal value” or its relevance to the Bogda heritage site. On the other hand, 35% of the respondents believed that the glaciers, lakes, forests and wild animals should be protected. However, this probably stems from the traditional concepts of Kazakh pastoralists which support environmental protection, rather than a clear cognition of World Heritage values (

Figure 4).

Question: Do you know about the outstanding universal values of Bogda heritage site?

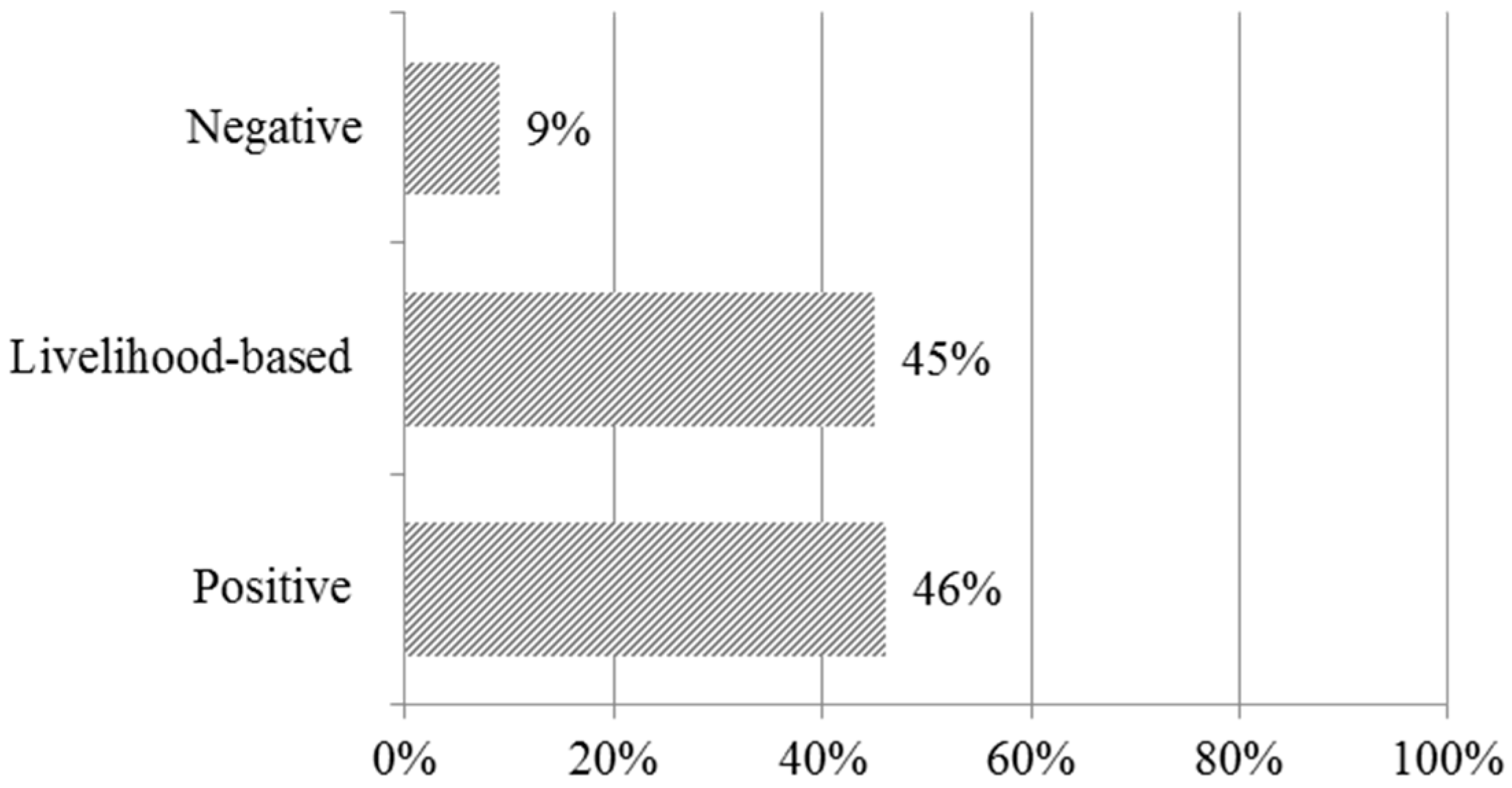

4.3. Attitudes towards Community Participation in Heritage Conservation

The protection of the Bogda heritage site is ultimately inseparable from the lifestyles and involvement of local residents and a strong relationship exists between the interests of the community residents and heritage conservation. They and their ancestors have been sustained by the Bogda environment for generations. In the survey, 46% of respondents show a positive attitude towards participation in the conservation of the Bogda heritage site. Furthermore, essentially the same proportion (45%) of respondents asserted that they are willing to participate in heritage conservation under the premise that their normal life will not be affected. Only a minority (9%) claimed that they wish to have nothing to do with the heritage conservation (

Figure 5).

Questions: Would you like to participate in heritage conservation?

The greatest contribution that community residents had made for heritage protection, was their role in the implementation of the grazing ban policy, which effectively alleviated pressure on the grasslands and facilitated ecosystem restoration. They abandoned the lifestyle that Kazakhs had followed for generations, altering their lifestyle from nomadism to the provision of tourism services.

Table 2 provides reasons for respondents’ willingness to participate in heritage protection and implement the grazing ban policy. Almost one fifth (18%) of respondents believe that they would be compensated for participating, such as through receipt of the grassland ecological protection award following the grazing ban. A smaller (15%) proportion simply state that they are willing to obey the government’s policies and regulations regarding heritage conservation. More than a third (35%) believes that the conservation of Bogda heritage site will protect and ensure the survival of their beautiful homeland. Almost as many (32%) assert that the Bogda heritage site has been left to them by their ancestors, so they are obligated to protect it for future generations in order that it can exist for ever. The investigation shows that the most of the residents are willing to participate in heritage conservation, because they have high attachment to it, particularly as a place where Kazakh people have lived for generations.

4.4. Participatory Approaches and Compensation

Table 3 shows the main means through which residents are willing to participate in protection of the heritage. Just under a fifth (17%) was willing to change their activities to keep negative impacts at the lowest level. For example, in order to protect the grassland vegetation at the heritage site, they abandoned traditional animal husbandry, choosing to be employed in tourism within a restricted area. Almost a third (31%) claimed that they will take the initiative to stop environmentally destructive behaviors, including littering by tourists, and trampling of grass. A small proportion (13%) are willing to participate in protection as staff, such as protecting the forests, supervising the grasslands, controlling fire, and patrolling the mountains, amongst other daily protection and management tasks. A similar proportion (12%) asserted that they are willing to participate in demonstration meetings related to planning and major projects, such as the development of heritage tourism, and changes land use, hoping that the administrators and development company would seek the views and suggestions of residents. Just over a quarter (27%) indicated that they are willing to supervise the management and development process of the Bogda heritage site as the host. These results show that most of the residents are willing to take proactive protection measures.

The pastoralists at the Bogda heritage site have abandoned the grazing land where their ancestors had raised animals, given up the lifestyle that had been passed on from generation to generation. They were redeployed and required to adopt a new lifestyle in order to protect the environment and its biodiversity. For this they deserve to receive compensation. As can be seen from

Table 4, the residents hope to obtain compensation for their role in the protection of the heritage site. A third (33%) indicated the need for financial assistance, hoping that the value of the grassland ecological protection award would be higher. A third (34%) hoped that employment opportunities will be provided, i.e., that their children will be able to work as part of the management committee or development company. A small proportion (9%) wished to obtain training in reception skills so as to improve and benefit from the tourism operation. Somewhat similar proportions hoped that support policies will be introduced to ensure a reliable supply of customers (12%) and that the government will help them to solve problems (13%), such as medical treatment, education facilities, and employment for people with disabilities.

5. Discussion

5.1. Relationships between Residents and the World Natural Heritage

The survey results show that approximately a third of respondents have no idea what World Natural Heritage really means, and most of the respondents do not understand the World Natural Heritage values of Bogda. Probably stemming from the traditional concepts of Kazakh pastoralists, which support environmental protection, more than half of the residents recognize that the Bogda World Natural Heritage should be well protected. Their awareness and knowledge regarding the natural resources of the area can underpin positive attitudes towards engagement of the local community in conservation activities. However, following successful nomination, the administrators of the heritage site need to explain and publicize the heritage values, reasons for protection of the heritage and the meaning of World Heritage to residents.

5.2. Relationships between Residents and Heritage Conservation

The study indicates that there is potentially a synergistic relationship between heritage resources conservation and the community residents. Firstly, the main reason that they are willing to participate in the conservation of heritage resources is not because Bogda has been designated a World Heritage Site; rather it is because Bogda has been their homeland for generations and they appreciate its environmental values. Secondly, if they are to support the conservation initiative, then it is important that they not be disadvantaged. While the adaptive ability of the residents is not consistent, as is shown in differences in abilities to operate and manage tourism reception service. Families with insufficient labors and reception skills tend to take a negative attitude towards conservation policy, as seasonal income from tourism cannot cover their annual family living expenditures.

5.3. Relationships between Community Development and Heritage Conservation

The community residents are redeployed and required to transform from a traditional nomadic lifestyle to participants in the tourism industry in order to protect the eco-environment and biodiversity. The residents bear the responsibility of the heritage conservation, so as to avoid reducing the initiatives of heritage conservation, they deserve to receive compensation and obtain fair interests. While one-time financial compensation is considered to be a short-term mechanism which is not sustainable in the long term. An ongoing compensation mechanism is required that rewards the community for participation in heritage conservation. In order to realize the sustainable relationships between heritage conservation and community development that is required, the administrators of the heritage site should adopt policies to mobilize the positive attitudes of residents towards participation in the conservation of natural resources by supporting tourism initiatives that may provide an ongoing source of employment and income.

As a minimum, sustainable development implies that attention is given to each of environmental, economic and socio-cultural matters. In the case in question, the sedentarization of a nomadic population of herders will reduce pressures on the grasslands as a whole, at the cost of increased impacts in and around the villages from both residents and tourists. However, such pressures may be managed more easily when they are concentrated.

Economically, a predominantly subsistence economy has been replaced by one that requires cash. In the short-term, compensation payments go some way to meeting monetary needs. From a longer perspective, it remains to be seen if tourism can provide reliable jobs and incomes to support the new settlements. Unless tourism is developed well or other sources of income are found, there is a risk that one form of poverty will be replaced by another.

Socio-culturally, the way of life of the nomads has been dislocated and their lifestyles have been changed. They stand to gain from greater access to medical assistance, education, electricity and other aspects of the modern world. Paradoxically, tourists are likely to be more interested in their traditional than modified ways, so in order to gain from tourism, they will need to re-create and re-position a lost culture and share it in forms that are accessible to visitors.

6. Conclusions and Implications

This paper has examined the perceptions and attitudes of pastoralists in northwest China who have been re-settled as a result of their rangelands being incorporated into a World Heritage Site. Though poor materially, for generations they have survived within a magnificent environmental setting. Now their lives have been dislocated and they are expected to support themselves in a new way, probably through tourism. They have very limited knowledge of the plans that exist for their pasturelands, although they appreciate its many values, and they are willing to support environmental protection, in part because it fits with their traditional perspectives on environmental husbandry.

Local community has a strong stake in the local heritage site and may be an important force in its conservation, management and development. Positive and sustainable relationships between a heritage site and the community can promote its protection. A “Community co-management framework” should be established to promote an atmosphere of open communication, ensure the voluntary participation of the community, and guarantee decisions by consensus, rather than the enforcement of decisions made by outsiders using legal and political means. For this to occur, a number of other initiatives will need to be taken, so that residents can participate in the making of decisions for the protection and management of the heritage site. A “community co-management framework” should include the following:

Employment and skills training should be provided for the residents, as well as access to capital, so as to guide them in adjusting their production system and lifestyle, and gradually ease their dependence on natural resource utilization.

The local residents are familiar with the natural environment of the heritage site. Thus, the local knowledge can be used in the day-to-day management of the forestry administration, in fire control and patrols, amongst other protection tasks. Residents can also be employed in monitoring to reduce acts of poaching and illegal felling, and to provide information for the monitoring of environmental pollution, prevention of natural disasters and undertaking heritage resource surveys at the heritage site.

When making relevant management decisions, such as the implementation of major projects, tourism planning, community planning, and border adjustment, residents should be encouraged to participate in meetings regarding land use planning and tourism development planning at the heritage site, so that the administrators can learn from them and understand their desires and abilities.

Due to their environmental knowledge and awareness of the need for conservation of resources, the community residents can gradually be transformed from the receivers of education about heritage to disseminators of information regarding heritage values to visitors, thereby contributing in new ways to the protection of heritage and harmonious development of heritage protection and community development.

At present, the study residents are in the early stages of adapting to their new situation and it is unclear whether, what or when initiatives will be taken to ease their adjustment. Thus, there is a need to monitor both what is done, and residents’ reactions to policy and management changes, in order to better their conditions, learn from experience and identify actions that may be relevant to other natural heritage locations.

Acknowledgments

The research was funded by the Western Doctoral Foundation of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. XBBS201210), Science and Technology Service Network Initiative of CAS (KFJ-SW-STS-181) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41301163). We also thank all of the respondents who completed the questionnaires.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to designing the research and the questionnaire, as well as writing the manuscript. Fang Han, Hui Shi, Qun Liu carried out the suvey. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- West, P.; Brechin, S.R. Resident Peoples and National Parks: Social Dilemmas and Strategies in International Conservation; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cernea, M.M.; Schmidt-Soltau, K. Poverty Risks and National Parks: Policy Issues in Conservation and Resettlement. World Dev. 2006, 34, 1808–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, S.K.; Weber, K.W. Managing resources and resolving conflicts: National parks and local people. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 1995, 2, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.; Geisler, C. The social consequences of protected areas development for resident populations. Soc. Nat. Resour. 1990, 3, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinen, M.N. Park—People Relations in Kosi Tappu Wildlife Reserve, Nepal: A Socio-economic Analysis. Environ. Conserv. 1993, 20, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, J.N.; Kellert, S.R. Local attitudes toward community-based conservation policy and programmes in Nepal: A case study in the Makalu-Barun Conservation Area. Environ. Conserv. 1998, 25, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbadegesin, A.; Ayileka, O. Avoiding the mistakes of the past: Towards a community oriented management strategy for the proposed National Park in Abuja-Nigeria. Land Use Policy 2000, 17, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persha, L.; Fischer, H.; Chhatre, A.; Grawal, A.A.; Benson, C. Biodiversity conservation and livelihoods in human-dominated landscapes: Forest commons in South Asia. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 2918–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newmark, W.D.; Leonard, N.L.; Sariko, H.I.; Gamassa, D.M. Conservation attitudes of local people living adjacent to five protected areas in Tanzania. Biol. Conserv. 1993, 63, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, N.U. Local people’s attitudes towards conservation and wildlife tourism around Sariska Tiger Reserve, India. J. Environ. Manag. 2003, 69, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCleave, J.; Espiner, S.; Booth, K. The New Zealand People—Park Relationship: An Exploratory Model. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2006, 19, 547–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zube, E.H.; Busch, M.L. Park–people relationships: An international review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 19, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, M.-J.; Gagnon, C. An assessment of social impacts of national parks on communities in Quebec, Canada. Environ. Conserv. 1999, 26, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Chen, L.; Lu, Y.; Fu, B. Local people’s perceptions as decision support for protected area management in Wolong Biosphere Reserve, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 78, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirivongs, K.; Tsuchiya, T. Relationship between local residents’ perceptions, attitudes and participation towards national protected areas: A case study of Phou Khao Khouay National Protected Area, central Lao PDR. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 21, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ye, Y.; Wu, Q.; Jin, L.; Zhang, H. Residents’ Environmental Conservation Behaviors at Tourist Sites: Broadening the Norm Activation Framework by Adopting Environment Attachment. Sustainability 2016, 8, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, M.M.; Kari, F.B.; Yahaya, S.R.B.; Al-Amin, A.Q. Impact of residents’ livelihoods on attitudes towards environmental conservation behaviour: An empirical investigation of Tioman Island Marine Park area, Malaysia. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2014, 93, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutanga, C.N.; Vengesayi, S.; Muboko, N.; Gandiwa, E. Towards harmonious conservation relationships: A framework for understanding protected area staff-local community relationships in developing countries. J. Nat. Conserv. 2015, 25, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyman, S.L. The role of tourism employment in poverty reduction and community perceptions of conservation and tourism in southern Africa. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadd, M.E. Conservation outside of parks: Attitudes of local people in Laikipia, Kenya. Environ. Conserv. 2005, 32, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebua, V.B.; Agwafo, T.E.; Fonkwo, S.N. Attitudes and perceptions as threats to wildlife conservation in the Bakossi area, South West Cameroon. Int. J. Biodivers. Conserv. 2011, 3, 631–636. [Google Scholar]

- Kideghesho, J.R.; Roskaft, E.; Kaltenborn, B.P. Factors influencing conservation attitudes of local people in Western Serengeti, Tanzania. Biodivers. Conserv. 2007, 16, 2213–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maikhuri, R.K.; Nautiyala, S.; Raob, K.S.; Saxena, K.G. Conservation policy people conflicts: A case study from Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve (a World Heritage Site), India. For. Policy Econ. 2001, 2, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutamba, E. Community Participation in Natural Resources Management: Reality or Rhetoric? Environ. Monit. Assess. 2004, 99, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez-López, M.E.; García-Frapolli, E.; Pritchard, D.J. Local participation in biodiversity conservation initiatives: A comparative analysis of different models in South East Mexico. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 145, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norzaini, A.; Sharina, A.H.; Ibrahim, K. Public Education in Heritage Conservation for Geopark Community. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 7, 504–511. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).