Effect of Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) Measures on Active Living and Fear of Crime

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Crime Prevention through Environmental Design

2.2. Fear of Crime

2.3. Fear of Crime in Relation to Health

3. Conceptual Framework, Research Questions, and Hypotheses

(1) Do CPTED Measures Mitigate Residents’ Fear of Crime?

(2) Do CPTED Measures Encourage Residents’ Walking Activities?

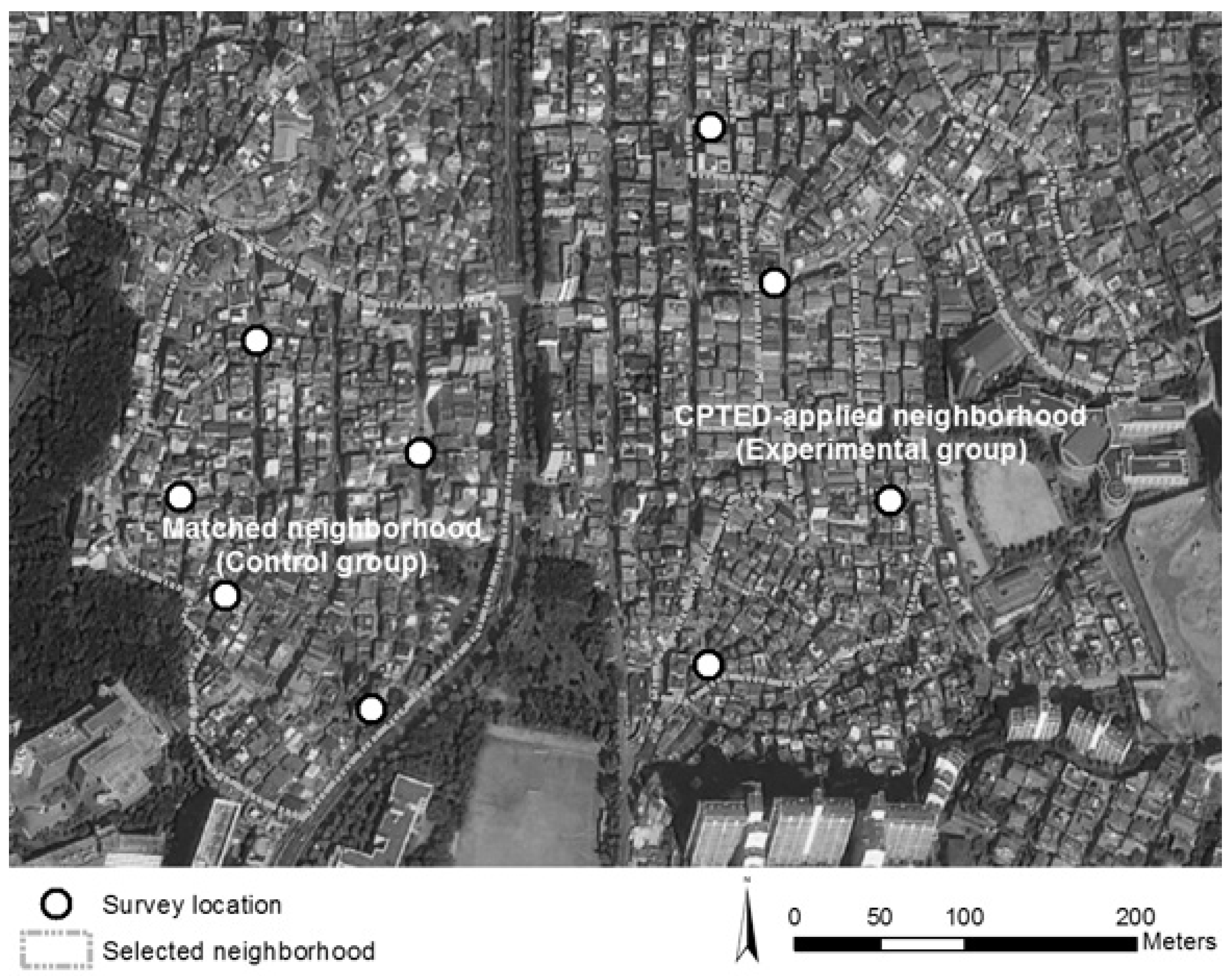

4. Setting and Method

4.1. Context

4.2. Survey Design and Data

4.3. Measures and Descriptive Statistics

4.4. Behavioral Modeling

5. Results

6. Implications and Conclusions

6.1. Implications

6.2. Shortcomings and Future Research

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Cozens, P.M.; Saville, G.; Hillier, D. Crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED): A review and modern bibliography. Prop. Manag. 2005, 23, 328–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-K.; Yoon, Y.-J.; Ahn, K.-H. A Study on Urban Crime in Relation to Land Use Patterns. J. Korea Plan. 2014, 49, 151–167. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Marzbali, M.H.; Abdullah, A.; Razak, N.A.; Tilaki, M.J.M. The influence of crime prevention through environmental design on victimisation and fear of crime. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 3, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyeyemi, A.L.; Adegoke, B.O.; Sallis, J.F.; Oyeyemi, A.Y.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I. Perceived crime and traffic safety is related to physical activity among adults in Nigeria. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzbali, M.H.; Abdullah, A.; Razak, N.; Tilaki, M. Validating crime prevention through environmental design construct through checklist using structural equation modelling. Int. J. Law Crime Justice 2012, 40, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.; Marzbali, M.H.; Tilaki, M. Predicting the influence of CPTED on perceived neighbourhood cohesion: Considering differences across age. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasuya, T.; Tamagawa, H. A study on the relations between criminal behaviors in purse-snatching and urban spaces. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2012, 16, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakip, S.; Abdullah, A. Measuring crime prevention through environmental design in a gated residential area: A pilot survey. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 42, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, C.R. Crime Prevention through Environmental Design; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt, R.E. Crime prevention through environmental design-a management perspective. Can. J. Criminol. 1983, 25, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, O. Defensible space: Crime Prevention through Urban Design; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.Q.; Kelling, G.L. Broken windows. Atl. Mon. 1982, 249, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, D.D.; Meeks, J.W.; Taylor, R.B. The physical environment of street blocks and resident perceptions of crime and disorder: Implications for theory and measurement. J. Environ. Psychol. 1992, 12, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D.; Wandersman, A.; Rich, R.; Taylor, R. The physical environment of street crime: Defensible space, territoriality and incivilities. J. Environ. Psychol. 1993, 13, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, L.; Junger, M.; Ongena, Y. The relation between residential property and its surroundings and day-and night-time residential burglary. Environ. Behav. 2014, 25, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, M. Fear of victimization: Why are women and the elderly more afraid? Soc. Sci. Quart. 1984, 65, 681–702. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, J.A.; Huebner, B.M.; Bynum, T.S. Fear of crime and criminal victimization: Gender-based contrasts. J. Crim. Justice 2006, 34, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, C.G.; Chalfin, A. Fear of walking outdoors: A multilevel ecologic analysis of crime and disorder. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 34, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, A.; Marzbali, M.H.; Tilaki, M.J.M.; Bahauddin, A. An assessment of the incivilities thesis: Examining gender differences. Int. J. Arts Sci. 2014, 7, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J. Validating new measures of the fear of crime. Int. J. Soc. Res. Meth. 2005, 8, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covington, J.; Taylor, R. Fear of crime in urban residential neighborhoods. Sociol. Quart. 1991, 32, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, D.M.; Furr, L.A.; Spine, M. The effects of neighborhood conditions on perceptions of safety. J. Crim. Justice 2002, 30, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Schweitzer, J.H.; Kim, M.J. The relationship of community characteristics to actual and perceived crime in urban neighborhoods. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2002, 6, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, R.; Azad, A.; Wirasinghe, S.C.; Hansen, S. Analysis of the influence of urban rail stations on neighbourhood crime. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2013, 17, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzbali, M.H.; Abdullah, A.; Tilaki, M.J.M. The effectiveness of interventions in the built environment for improving health by addressing fear of crime. Int. J. Law Crim. Justice 2016, 45, 120–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medway, D.; Parker, C.; Roper, S. Litter, gender and brand: The anticipation of incivilities and perceptions of crime prevalence. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valera, S.; Guàrdia, J. Perceived insecurity and fear of crime in a city with low-crime rates. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallal, P.C.; Reis, R.S.; Parra, D.C.; Hoehner, C.; Brownson, R.C.; Simões, E.J. Association between perceived environmental attributes and physical activity among adults in Recife, Brazil. J. Phys. Act. Health 2010, 7, S213–S222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallmann, B.; Bucksch, J.; Froboese, I. The association between physical activity and perceived environment in German adults. Eur. J. Public Health 2012, 22, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, R. Neighborhood disorder, perceived safety, and readiness to encourage use of local playgrounds. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 34, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weden, M.M.; Carpiano, R.M.; Robert, S.A. Subjective and objective neighborhood characteristics and adult health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 1256–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.G.; Cho, Y. Relationship between perceived neighborhood characteristics and vigorous physical activity among adult Seoul residents. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2009, 42, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arango, C.M.; Páez, D.C.; Reis, R.S.; Brownson, R.C.; Parra, D.C. Association between the perceived environment and physical activity among adults in Latin America: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.J.; Hong, S.Y. Likert type scale construction to fear about crime. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2007, 46, 191–222. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Golob, T.F. Structural equation modeling for travel behavior research. Transp. Res. B Meth. 2003, 37, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, D.; Davidson, N. Modifying the built environment: The impact of improved street lighting. Geoforum 1995, 25, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Operational Definitions | |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Construct | ||

| Fear of crime | I1: Frightened to pass through narrow alleys | |

| I2: Surprised if there’s someone on an almost deserted street | ||

| I3: Desire to detour if approaching a narrow alley | ||

| Endogenous Variables | ||

| Walking frequency | In a typical week, how many times do you walk in your neighborhood? | |

| ln (Walking frequency) | Natural log-transformed of walking frequency plus 1 | |

| Exogenous Variables | ||

| CPTED | CPTED (0 = not implemented; 1 = implemented) | |

| Access control | CCTV | There are sufficient CCTVs around the location (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) |

| Natural surveillance | Street lighting | Street lighting around the location is sufficiently bright (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) |

| Fence removal | Fence removal (0 = no; 1 = yes) | |

| Transparent fence | Presence of transparent fence (0 = no; 1 = yes) | |

| Territoriality | Mural | Presence of mural (0 = no; 1 = yes) |

| Paving pattern | Paving patterns or colors (0 = no; 1 = yes) | |

| Activity support | Community park | Presence of community park (0 = no; 1 = yes) |

| Community center | Presence of community center (0 = no; 1 = yes) | |

| Maintenance | Maintenance | Well maintained without vandalism or graffiti (0 = no; 1 = yes) |

| Occupied | Well-occupied area without any unused building or space (0 = no; 1 = yes) | |

| Socioeconomic status | Male | Gender (0 = female; 1 = male) |

| Age | Resident’s age | |

| Residence | Residence period (month) | |

| ln (Residence) | Natural log-transformed residence period | |

| Owner | Home ownership (0 = rent or lease; 1 = ownership) | |

| College | Educational level (0 = high school or lower; 1 = college or higher degree) | |

| High income | High monthly household income (>$5000) (0 = otherwise; 1 = yes) | |

| Middle income (base) | Middle monthly household income ($2000–5000) (0 = otherwise; 1 = yes) | |

| Low income | Low monthly household income (<$2000) (0 = otherwise; 1 = yes) | |

| Variables | Total | CPTED Mean (SD) | Non-CPTED Mean (SD) | Diff. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | Min. | Max. | |||||

| Fear of crime | I1 | 617 | 2.56 (1.21) | 1 | 5 | 2.46 (1.16) | 2.67 (1.26) | −0.21 * |

| I2 | 617 | 2.76 (1.26) | 1 | 5 | 2.76 (1.23) | 2.77 (1.29) | −0.01 | |

| I3 | 617 | 2.67 (1.29) | 1 | 5 | 2.62 (1.27) | 2.71 (1.30) | −0.10 | |

| Walking frequency | 617 | 7.00 (4.66) | 0 | 70 | 6.97 (4.37) | 7.03 (4.93) | −0.05 | |

| ln (Walking frequency) | 617 | 1.98 (0.42) | 0 | 4.26 | 1.98 (0.43) | 1.99 (0.40) | −0.01 | |

| CPTED | 617 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Access control | CCTV | 617 | 2.83 (1.06) | 1 | 5 | 2.97 (1.09) | 2.69 (1.01) | 0.28 * |

| Natural surveillance | Street lighting | 617 | 3.05 (1.01) | 1 | 5 | 3.17 (1.03) | 2.92 (0.99) | 0.25 * |

| Fence removal | 612 | 0.23 | 0 | 1 | 0.38 | 0.09 | 0.30 * | |

| Transparent fence | 612 | 0.22 | 0 | 1 | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.14 * | |

| Territoriality | Mural | 612 | 0.22 | 0 | 1 | 0.33 | 0.11 | 0.22 * |

| Paving pattern | 612 | 0.38 | 0 | 1 | 0.70 | 0.06 | 0.64 * | |

| Activity support | Community park | 612 | 0.22 | 0 | 1 | 0.32 | 0.11 | 0.21 * |

| Community center | 612 | 0.22 | 0 | 1 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.16 * | |

| Maintenance | Maintenance | 612 | 0.98 | 0 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.05 * |

| Occupied | 612 | 0.94 | 0 | 1 | 0.97 | 0.91 | 0.06 * | |

| Socioeconomic status | Male | 610 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.02 |

| Age | 598 | 48.41 (19.66) | 11 | 92 | 51.17 (18.64) | 45.72 (20.28) | 5.45 * | |

| Residence | 571 | 162.1 (165.4) | 1 | 912 | 157.3 (151.5) | 168.0 (178.3) | −21.0 | |

| ln (Residence) | 571 | 4.47 (1.29) | 0 | 6.82 | 4.50 (1.21) | 4.45 (1.38) | 0.05 | |

| Owner | 516 | 0.61 | 0 | 1 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.00 | |

| College | 481 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.03 | |

| High income | 384 | 0.11 | 0 | 1 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.06 | |

| Mid income | 384 | 0.42 | 0 | 1 | 0.40 | 0.44 | −0.04 | |

| Low income | 384 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 | 0.47 | 0.49 | −0.02 | |

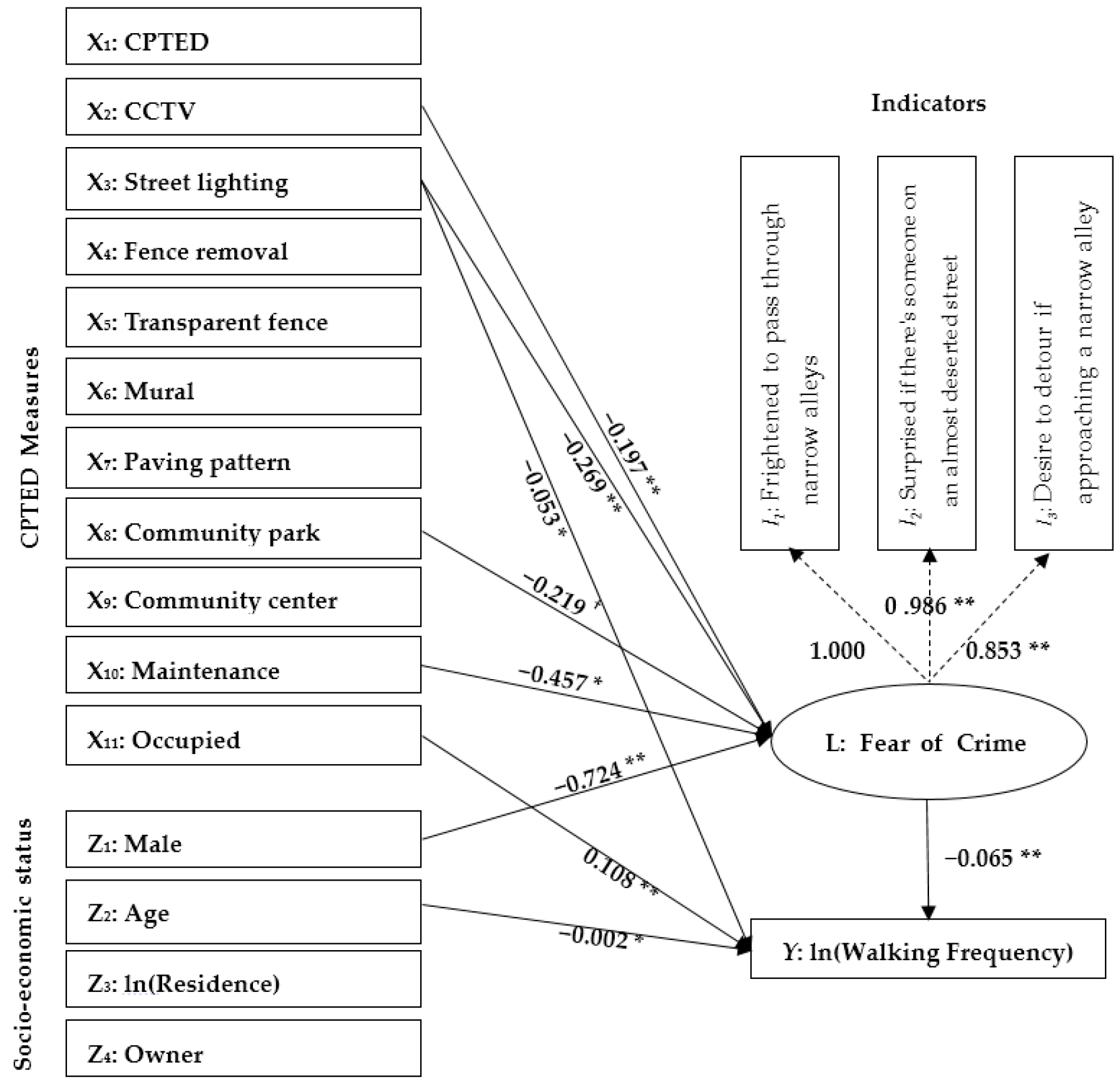

| Model 1: CFA (n = 617) | Model 2: SEM (n = 494) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | (Robust SE) | p-Value | Coef. | (Robust SE) | p-Value | |

| Measurement model | ||||||

| Latent variable: Fear of crime | ||||||

| I1: Frightened to pass through narrow alleys | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| I2: Surprised if there’s someone on an almost deserted street | 0.911 ** | (0.067) | 0.000 | 0.986 ** | (0.063) | 0.000 |

| I3: Desire to detour if approaching a narrow alley | 0.800 ** | (0.062) | 0.000 | 0.853 ** | (0.069) | 0.000 |

| Structural model | ||||||

| Exogenous variable: Fear of crime | ||||||

| CPTED | 0.012 | (0.139) | 0.929 | |||

| CCTV | −0.197 ** | (0.055) | 0.000 | |||

| Street lighting | −0.269 ** | (0.043) | 0.000 | |||

| Fence removal | −0.107 | (0.114) | 0.347 | |||

| Transparent fence | 0.050 | (0.115) | 0.665 | |||

| Mural | 0.132 | (0.111) | 0.238 | |||

| Paving pattern | 0.066 | (0.141) | 0.640 | |||

| Community park | −0.219 † | (0.126) | 0.081 | |||

| Community center | 0.180 | (0.120) | 0.132 | |||

| Maintenance | −0.457 * | (0.223) | 0.040 | |||

| Occupied | 0.110 | (0.233) | 0.636 | |||

| Male | −0.724 ** | (0.088) | 0.000 | |||

| Age | 0.003 | (0.003) | 0.353 | |||

| ln (Residence) | 0.025 | (0.041) | 0.551 | |||

| Owner | 0.003 | (0.103) | 0.973 | |||

| Exogenous variable: ln (Walking frequency) | ||||||

| Fear of crime | −0.065 ** | (0.024) | 0.008 | |||

| CPTED | −0.026 | (0.052) | 0.613 | |||

| CCTV | 0.015 | (0.016) | 0.340 | |||

| Street lighting | −0.053 * | (0.021) | 0.015 | |||

| Fence removal | 0.057 | (0.049) | 0.244 | |||

| Transparent fence | 0.034 | (0.056) | 0.549 | |||

| Mural | 0.046 | (0.053) | 0.388 | |||

| Paving pattern | −0.038 | (0.052) | 0.459 | |||

| Community park | −0.052 | (0.048) | 0.281 | |||

| Community center | 0.038 | (0.057) | 0.506 | |||

| Maintenance | 0.042 | (0.043) | 0.332 | |||

| Occupied | 0.108 ** | (0.040) | 0.007 | |||

| Male | −0.048 | (0.038) | 0.202 | |||

| Age | −0.002 * | (0.001) | 0.039 | |||

| ln (Residence) | 0.013 | (0.016) | 0.407 | |||

| Owner | 0.043 | (0.033) | 0.198 | |||

| Constant | 1.874 ** | (0.107) | 0.000 | |||

| (32) | 48.144 | 0.033 | ||||

| RMSEA | 0.032 | |||||

| CFI | 0.977 | |||||

| TLI | 0.952 | |||||

| SRMR | 0.015 | |||||

| Indirect Effects | Direct Effects on Walking Frequency | Total Effects on Walking Frequency | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects on Fear of Crime | Effects of Fear of Crime on Walking Frequency | Indirect Effects on Walking Frequency | |||

| CCTV | −0.197 | (−0.197) × (−0.065) = 0.013 | - | 0.013 | |

| Street lighting | −0.269 | (−0.269) × (−0.065) = 0.017 | −0.053 | −0.036 | |

| Maintenance | −0.457 | −0.065 | (−0.457) × (−0.065) = 0.030 | - | 0.030 |

| Occupied | - | - | 0.108 | 0.108 | |

| Male | −0.724 | (−0.724) × (−0.065) = 0.047 | - | 0.047 | |

| Age | - | - | −0.002 | −0.002 | |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.S.; Park, S.; Jung, S. Effect of Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) Measures on Active Living and Fear of Crime. Sustainability 2016, 8, 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8090872

Lee JS, Park S, Jung S. Effect of Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) Measures on Active Living and Fear of Crime. Sustainability. 2016; 8(9):872. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8090872

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jae Seung, Sungjin Park, and Sanghoon Jung. 2016. "Effect of Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) Measures on Active Living and Fear of Crime" Sustainability 8, no. 9: 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8090872

APA StyleLee, J. S., Park, S., & Jung, S. (2016). Effect of Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) Measures on Active Living and Fear of Crime. Sustainability, 8(9), 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8090872