1. Introduction

Cities are hubs for ideas, commerce, culture, and innovation, as well as living place for half of humanity. They are also confronted with many challenges such as demographic or climatic change, congestion, a declining infrastructure, pollution, or poverty. Therefore, at the United Nations Sustainable Development Summit, in September 2015, world leaders decided to focus on the 17 Sustainable Development Goals for making cities more resilient [

1]. A city may then be considered resilient, when all urban actors (governmental representatives as well as citizens) share sufficient know-how and creativity, in order to manage extraordinary situations [

2]. Adger [

3] introduces the term

social resilience and defines it “as the ability of groups or communities to cope with external stresses and disturbances as a result of social, political and environmental change”. Self-organization, collective action and social-learning processes are supposed to activate and promote identification of explicit social strengths and connections to place, and thus are seen as supportive factors of community resilience [

4]. Likely, in their recent work on urban resilience and climate change adaption, Kim and Lim [

5] examine resilience from an evolutionary perspective and as a socio-political process, and identify “collective decision-making”, “cooperative behaviour and planning”, as well as “collective learning”, and “governance as a political process involving society at large” as key components of resilience building processes. The term evolutionary, they state, includes “flexibility, diversity and adaptive learning” and refers less to the adaptability to sudden, external shocks, but more to an ongoing change of a system [

5,

6]. All these resilience factors hold much promise for social learning processes [

7,

8,

9], whereby it is not a linear progression or a certain state which is to be achieved, but the process of searching, foresighted learning, action, and innovation itself [

9]. These insights prompt the question of how to develop flexible urban governance structures and institutions that effectively organize the interaction and learning processes of urban actors to support urban resilience and sustainability [

2].

The involvement of citizens in urban decision-making and planning processes has already widely turned into common practice. Public participation is expected to increase legitimacy, quality, acceptance, and efficacy of decisions [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14], and to foster empowerment of citizens [

15,

16]. Thus, citizen participation is even appraised as a key element towards sustainability and resilience on the local level [

17,

18]. While generally acknowledging participation as a crucial factor in future policy and decision-making, various studies point out shortcomings and disappointing results of the participatory processes [

15]. In practice, citizen involvement focuses on problems that have been pre-defined by political and administrative representatives, who invite citizens to collaborate on case-related solution finding [

19]. Citizens themselves are usually neither empowered to actively prompt and initiate participatory processes nor are they involved in negotiation processes regarding problem definition [

13] and long-term processes of institutional change. Processes usually remain controlled by public government [

15], which fails in “being open and adaptive to initiatives that emerge from the dynamics of civil society itself” [

15]. This gives rise to the assumption that there is currently untapped potential for future involvement of citizens to improve urban resilience, which might be leveraged by reconsidering (power) relations and interaction between government and society.

Most scientific contributions and practice guidelines within the field of participation refer to Arnstein’s pioneering work from 1969—the ladder of citizen participation [

20]—which still dominates the way to think about the nature of participation [

21]. Her approach grasps participation as the distribution of case-related decision-making power from government to citizens and is widely criticized to restrict participatory processes in terms of problem definition and space for negotiation and cultural change [

13,

22]. Since 1969, of course circumstances and understandings of how to govern a city have undergone fundamental transformations. These include first and foremost the shift from government (hierarchical and central steering, “top-down”) to governance (interactive policy-making, involving society, network perspective, “bottom-up”).

Concurrently, another discourse gains importance in urban planning, which, in contrast to participation, does not originate from a governmental perspective but from the citizens’ point of view: the growing attention to collective action, self-organization, and the management of urban commons [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. In his discussion on the interconnection between social and ecological resilience, as an example of resilient institutions, Adger [

3] highlights the “ability of institutions of common property management to cope with external pressure and stress”. Considering this resilience perspective, participatory practices in urban development might also benefit from insights from the commons research.

Therefore, the core question of this research is, if and how the discourse on collective action and urban commons—in particular Elinor Ostrom’s design principles for the sustainable management of the commons [

28]—may provide insights to ease restrictions in thinking about participation from a governmental perspective and to effectively design and organize long-term collaboration in urban development. It focuses less on different types of shared urban resources, but imagines the whole city itself as a commons that needs collaboration, social learning, and experimentation for its long-term sustainability and resilience.

2. Methods and Structure of the Paper

Based on a comprehensive literature review, the paper critically examines these two different, yet related, discourses on urban governance: participation [

10,

21,

22,

29] and self-organized collective action [

15,

23,

28,

30,

31]. Both address the interaction of citizens and government, albeit from different perspectives: on the one hand from the viewpoint of the government, selectively handing some of its power over to citizens, on the other hand from the perspective of citizens who self-organize for a collective management of urban commons (for structure and methodological approach of the paper see

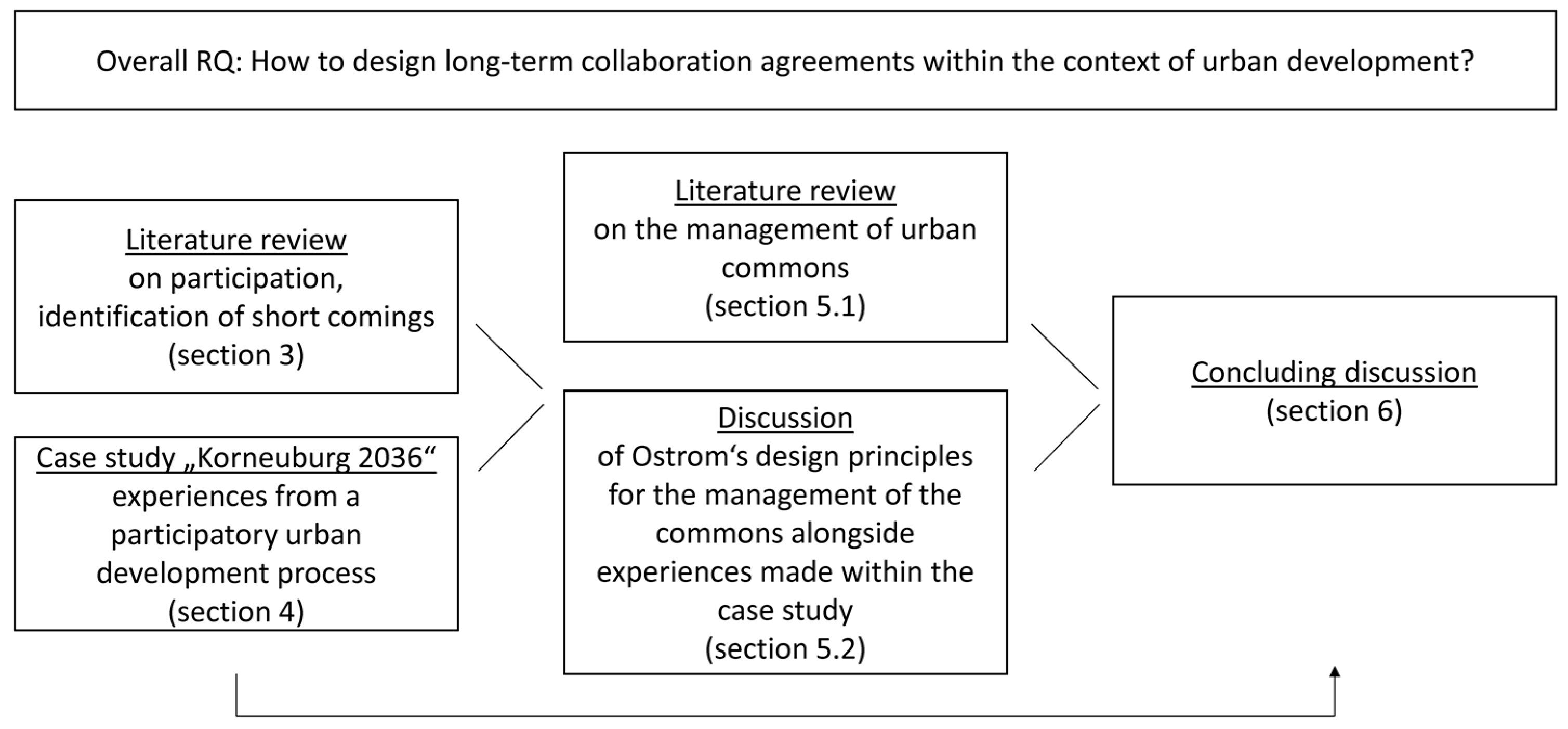

Figure 1).

Section 3 reviews the critical discussion of Arnstein’s metaphor of the ladder of citizen participation. It questions the metaphors’ limitations and the need for reinterpretation from the resilience perspective alongside four key fields of action, which were derived and condensed from literature.

Based on an empirical case study of the Austrian city of Korneuburg, it is examined if and how the collective action literature may help overcome some of the self-criticisms and shortcomings of the participation discourse. In

Section 4, we present a three-year transdisciplinary urban development project that the authors have been involved in as researchers. The project has developed from a self-organized citizen initiative to a broad participatory process—involving actors from government, city administration, all political parties, citizens, as well as an external interdisciplinary team of experts from two universities and a private consultancy—which ended in a long-term collaboration agreement between citizens and the municipal government. It is a commitment to share responsibility for future urban development, and its regulatory framework has neither been defined from a classic governmental point of view, nor from the perspective of only self-organizing citizens.

Section 5 briefly introduces the discourse about the urban commons and the eight design principles, which Ostrom derived from a profound analysis of case studies [

28]. Her design principles are discussed alongside the experiences from the case study, focusing on their relevance for related questions which could not be answered with the help of participation literature and experience. In other words, the design principles did not inform the participatory practice of the case study from the beginning, but were used as an analytic framework to discuss the case from an ex-post perspective. The concluding discussion intends to build a bridge between the framework of participation and the collective management of urban commons in order to contribute much needed insights on how to co-manage cities to improve their sustainability and long-term resilience.

3. A Review on Public Participation—The Cracks in the Ladder

Most attempts to frame and classify citizen participation refer to Arnstein’s pioneering work from 1969, the ladder of public participation, describing a continuum of increasing stakeholder involvement [

12,

14,

21]. It stems from a time when governments were used to making decisions on their own and just slowly began to involve citizens. Thus, Arnstein [

20] intended to offer a simplified typology of citizen participation, illustrating “the extent of citizens’ power in determining the end product” as hierarchical rungs, ranging from levels of non-participation (manipulation and therapy) through levels of “tokenism” (informing, consultation, and placation) to levels of citizen power (partnership, delegated power, and citizen control). Arnstein accentuates that, restricted to the first two levels, participation is not to be expected to change the status quo [

20]. Thus, the hierarchical metaphor of a ladder suggests higher levels of participation to be preferable to those on lower rungs, and citizen power to be seen as the overall goal of participation, on the one hand [

22,

29,

32]. On the other hand, participation mainly remains good will and offer by public authorities, who decide when, how, and to what extent to hand over power and to involve citizens in case-related decision-making. Arnstein’s work formed the base for widespread further research [

12,

33] and also for the implementation of participatory procedures in practice.

Numerous scientific contributions point out shortcomings and weak points of participatory practice and formulate a number of suggestions for best practice participation [

12] or refine Arnstein’s ladder metaphor in different ways [

22,

32,

34]. In line with other contributions [

21,

30], we argue that even a bigger step—not only on, but beyond the ladder—needs to be taken to overcome restrictions in conceptual thinking about the nature of participation, which up to now has been determined from the viewpoint of governmental control and power re-allocation, and to reshape the underlying ontology and epistemology of participation [

21].

As the relationship between state and citizens is undergoing a profound process of change in post-modern societies [

35], and Arnstein’s hierarchical conception of participation fails to capture the full complexity of this transformation; this is probably the major source of criticism [

21,

22,

29,

31]. The mere focus on the allocation of power might even lead to an adversarial picture of participation, as “contest between two parties” [

22], a “power struggle between citizens to move up the ladder” and the government [

21], and “based on the idea of a conflict between the

powerful and the powerless” [

15]. Thus, it is reinforcing the traditional dichotomy between those who govern and those who are governed. Such a competitive relationship is supposed to prohibit and exclude opportunities for trustful collaboration, sharing experience and knowledge, harnessing multiple perspectives, and shared decision-making [

22,

36]. The following sections provide a synopsis of critical examinations of the participatory framework in four key fields of sustainable urban development, which underpin the need for a broader approach and new perspectives in thinking about participation.

3.1. The Importance of Common Problem Identification and Framing

Urban development is increasingly challenged by complex problems with ambiguous problem definitions or unclear, conflicting, and dynamically changing goals and multiple stake-holding [

20,

37]. Referring to change, disturbance, complexity, and uncertainty, resilience scholars emphasise the inclusion of diverse types of knowledge, experiences, and approaches of those who are affected by decisions, not only in solution-finding, but also and foremost in problem perception and identification [

37,

38,

39,

40]. One expression of traditional participation processes is the hierarchical division of responsibilities. This implies that authorities define the nature of the problem [

15], the way to handle it, and thus a priori set the scope for citizen involvement. This “failure to consider the essential role of users in framing problems and not simply in designing solutions” [

22] contrasts with findings from various participatory experiences but also resilience literature, which highlight the importance of involving citizens as soon as possible, when there is maximum scope and openness for co-creation of a diversity of response options through social learning [

14,

37,

39,

40,

41,

42].

While “existing problem definitions or alternatives often remain unquestioned, they shape participatory processes in important ways” [

21,

32] and “existing dominant frameworks are reproduced and reinforced.”[

13] This results in a call for a re-conceptualization of roles, responsibilities, and purposes of those involved, “not along the lines of participation mediated in terms of power […] but as a process of social learning about the nature of the issue itself and how it might be progressed” [

21]. In the beginning of a project there is the key opportunity to shape a process, when ground rules are established in a collaborative manner.

It is also known from findings of group dynamics that especially this first phase of common problem framing, defining, and structuring the process and creating trust is of special importance for the success of a process and leads to greater identification with the issue itself, and thus to greater motivation for collaboration [

42]. Yet, in Arnstein’s model, the need to devote time and common expertise to problem definition and to build consensus around the agenda and goals are not considered.

3.2. The Value of the (Learning) Process

Problem solving does not occur by delegating power but through intense processes of knowledge exchange and social learning [

43,

44,

45]. Social learning and experimentation are key strategies for building resilience [

5,

39,

40]. Thus, decision-making has become a social issue, which embraces the mobilization of different knowledge sources in a social learning process [

32]. Collins and Ison [

21] even propose social learning as the highest level of participation, i.e., adding to the sequence of information, consultation and participation at the level of social learning.

Instead of adding another rung to the ladder, other critics fundamentally question Arnstein’s approach to measure successful participation in terms of its extent (the more power delegated to citizens, the better). Not achieving citizen control thus might be conceptualized as failure or delegitimization of a process [

21]. Instead of shifts in power relations, several scholars highlight the quality, dynamics, and flexibility of the process as measures for participation success [

21,

22,

29,

36,

42,

46]. For successful process design it seems to be less important to what extent citizens get involved, but rather to co-define the adequate method, the relevant actors and the extent of their involvement for each phase of a process to ensure social learning among governmental and non-governmental actors. Effective processes can mix information, consultation, or decision making successfully [

29]. Thus, Arnstein’s focus on power allocation, “limits effective responses to the challenge of involving users […] and undermines the potential of the user involvement process” [

22].

3.3. The Need for Institutionalization and Reliability of Participatory Practice

A continuous and stable, long-term, and process-oriented involvement of citizens may be the core driver for the future adaptability of cities to challenging situations or uncertain future change. As Berkes [

47] states, ad hoc public participation cannot be considered as urban co-management, but it requires “some institutionalized arrangement for intensive user participation in decision-making”. Long-term processes of (social) learning (see

Section 3.2 above) and joint problem framing (

Section 3.1), as well as the building of associated capacities and skills of all actors involved, take time and require trustful and reliable structures. Thus, “constructing an effective co-management arrangement is not only a matter of building institutions”, but also building trust between the parties and social capital in general is of high relevance [

47].

Several scholars point at the limitations of traditional on-off participation and highlight shortcomings of Arnstein’s approach in terms of establishing continuity, trust building, and long-term empowerment of citizens [

22,

34]. Regularity and continuation of public participation are even expected as “prerequisite for greater identification with political decisions and use of offered participation” [

14,

19]. And indeed, “supporting and promoting, high-quality, ongoing public participation is a key growing concern of local governments” [

18].

3.4. Community Initiated Processes and Self-Organization

Climate change, demographic change, and the recent economic crisis contribute to the complexity and uncertainty of urban development. Due to this complexity and uncertainty, political action and decisions become less traceable and understandable for citizens, which can result in a growing distance between political action and the citizens’ lives. And indeed, one can observe scepticism about formal authority, an increasing wish for autonomous collective action to co-design cities based on a shift in social values from subordination towards self-organization [

19]. Self-organization emerges from citizens themselves, who initiate, work, and decide on projects autonomously, while governmental actors are not involved at all or assume a supportive role. Creating opportunities for self-organization is a key-strategy for building resilience [

37,

39,

40].

Arnstein’s approach focuses on a governmental perspective of participation. In this conceptualization, citizens themselves do not prompt and initiate participatory processes actively (apart from reactive protest and resistance against governmental action). Even for citizen control, the highest rung of the ladder, symbolizing decision-making power handed over to participants, still has the government holding the origin, structuring, and control of the process. Self-organized autonomous citizens as “active agents, interacting with each other and organizing themselves in order to get things done, both for themselves and for others in their environment” [

30] do not fit into Arnstein’s conceptualization.

4. Case Study “Korneuburg 2036”

The following sections provide an overview of a broad participatory process in the Austrian city of Korneuburg. It was realized within the framework of a transdisciplinary urban development project from April 2012 to December 2015, which was financed by the city itself and the urban renewal programme of the provincial state of Lower Austria.

4.1. Description of the City and the Project Background

Korneuburg is a medium scale district capital in Lower Austria with about 13,000 inhabitants and is located at the Danube river next-door to the metropolis of Vienna. It grappled with an unbalanced municipal budget, considerable population increase due to its vicinity to Vienna, as well as having heterogeneous interests and perceptions of its identity and image between the poles of urbanity and village quality of living [

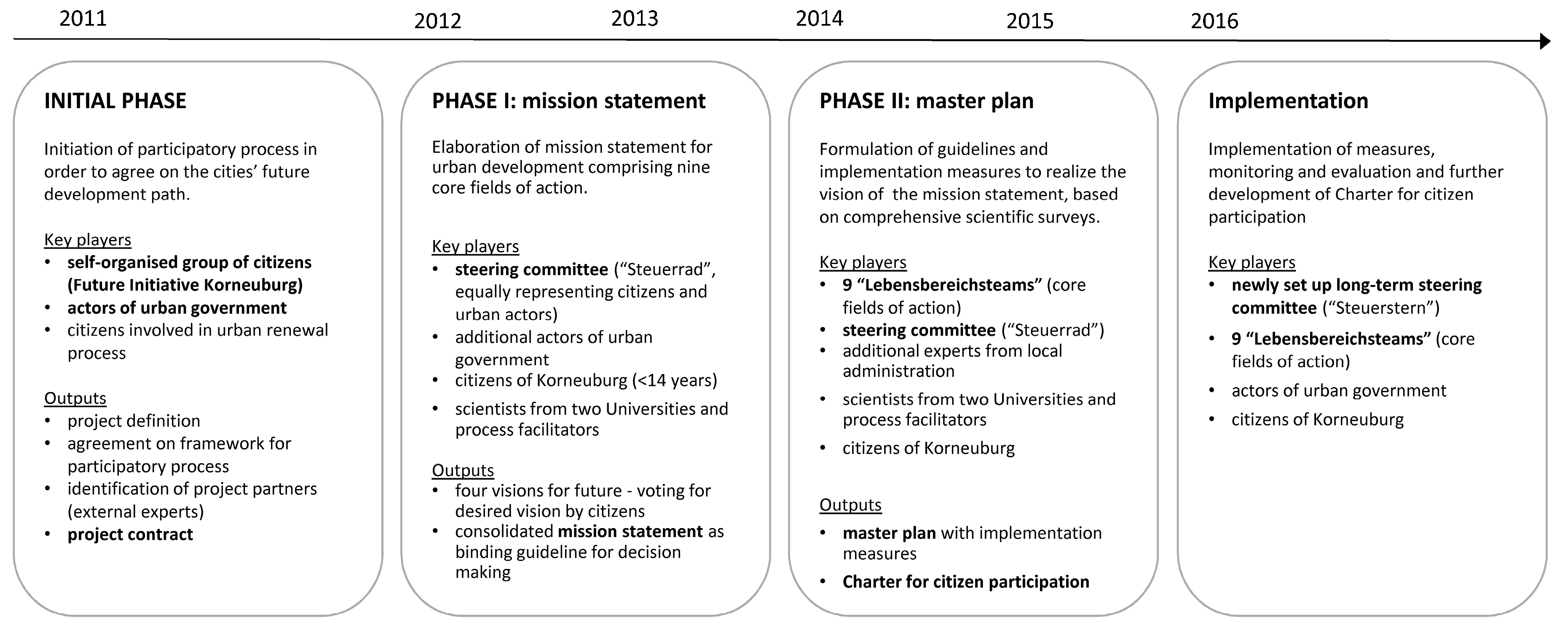

42]. Moreover, the city had to find sustainable solutions for various demanding tasks such as recurrent flooding of the Danube, groundwater pollution, and the controversial plans for building an additional motorway exit. Starting in 2011, a group of self-organized citizens convinced the municipal government to develop a mission statement for urban planning in close collaboration with citizens and external experts (phase 1: “Leitbild” as shown in

Figure 2; for details see [

42,

48]). The city committed itself to the mission statement as a binding guideline for decision-making in future urban planning (e.g., for land use zoning, traffic, and social infrastructure planning). It was to ensure a targeted development of the city, instead of uncontrolled growth. In phase 2, a master plan was developed in the same participatory manner comprising guidelines and measures for implementation of the desired vision for the next 20 years. As a complementary “spin-off product,” a Charter for citizen participation—an agreement for future collaboration between the city and its citizens—has been elaborated and anchored within the master plan.

All project phases were supported by scientists from two universities and various disciplines, as well as professionals in facilitation and moderation. The scientific experts provided methodological support (such as the use of scenario technique in phase 1), relevant data and knowledge as a basis for formulating implementation measures (especially in phase 2) and continuously attended almost all meetings of the steering committee and thus participated intensively in the process of knowledge exchange and social learning (for the role of scientists and the transdisciplinary process see [

42]).

4.2. The Role and Dynamics of Citizen Participation in the Course of the Process

Initiated by self-organized citizens and implemented as a broad participation project, the process generated considerable self-reinforcing tendencies over time. Each and every step gave an impetus for further development and for searching ways to consolidate newly evolving ideas and structures. During the formulation of the mission statement (phase 1), the vision of a new cooperative culture between citizens and municipal government was identified as a central pillar for future urban governance. Thus, in phase 2, when elaborating the master plan, the issue of participation became a cross-sectional topic considered in designing implementation measures in all of the nine fields of action. Finally, a collaboration agreement was formulated, including rules and quality criteria for future citizen participation (Korneuburger Charter of citizen participation).

During all project phases, citizens collaborated at eye-level with representatives of all four political parties and the city administration. This very open and trustful atmosphere can be mainly traced back to the communicative competences and constellation of actors involved, as well as by a carefully chosen eye-level approach by facilitators and external experts. Although the mayor’s party has held and even increased the overall majority within the local council in an election at the middle of the project, they continued to focus very much on cooperation and consensus between all political parties and urban stakeholder groups.

The initial phase of problem framing, selection of external experts, and project definition depended more on informal interaction. During phases 1 and 2, a steering committee (so called “Steuerrad” resp. “steering wheel”) had been installed to assume the responsibility for the process progress. Besides the mayor and representatives of all political parties and local administration, an equal number of citizens were involved (one mayor, six representatives of local government, seven citizens) plus two representatives for each person (42 persons in total). The steering committee made all strategic and content-related decisions in the project (consensus oriented) and prepared all issues for the local council, who of course had the final say at project milestones. Thus, citizens were not only involved on the level of solution finding, but in all strategic planning of the process right from the beginning. The city council was very supportive in the open-ended process and agreed to a binding direct vote, where all citizens of 16 years or older could decide between four different scenarios for Korneuburg in 2036. These scenarios were the outcome of a broader participation process involving hundreds of citizens via school and city events in phase 1 and formed the basis for the mission statement.

All project-related outcomes resulted in unanimous decisions within the city council (approval of the mission statement, the master plan, the Charter for citizen participation, as well as decisions on how to proceed with the process by all four parties represented in the council). This confirms the high level of trust and acceptance of the committee’s work by the municipal government. Additionally, nine teams for each of the core fields of action were established (“Lebensbereichs”-teams, LB-teams), such as urban planning, mobility, communication and participation or health, each jointly led by one citizen and one politician (both members of the Steuerrad). While membership in the steering committee was limited to a closed group, who were participating continuously, the LB-teams were open to all citizens/municipal representatives interested in the respective topic. These groups were responsible for elaborating concrete implementation measures for their respective action fields that were in line with the mission statement and were then finally integrated into a master plan defining the actions and responsibilities for the next 20 years.

4.3. The Charter for Citizen Participation—A Guideline for Future Collaboration

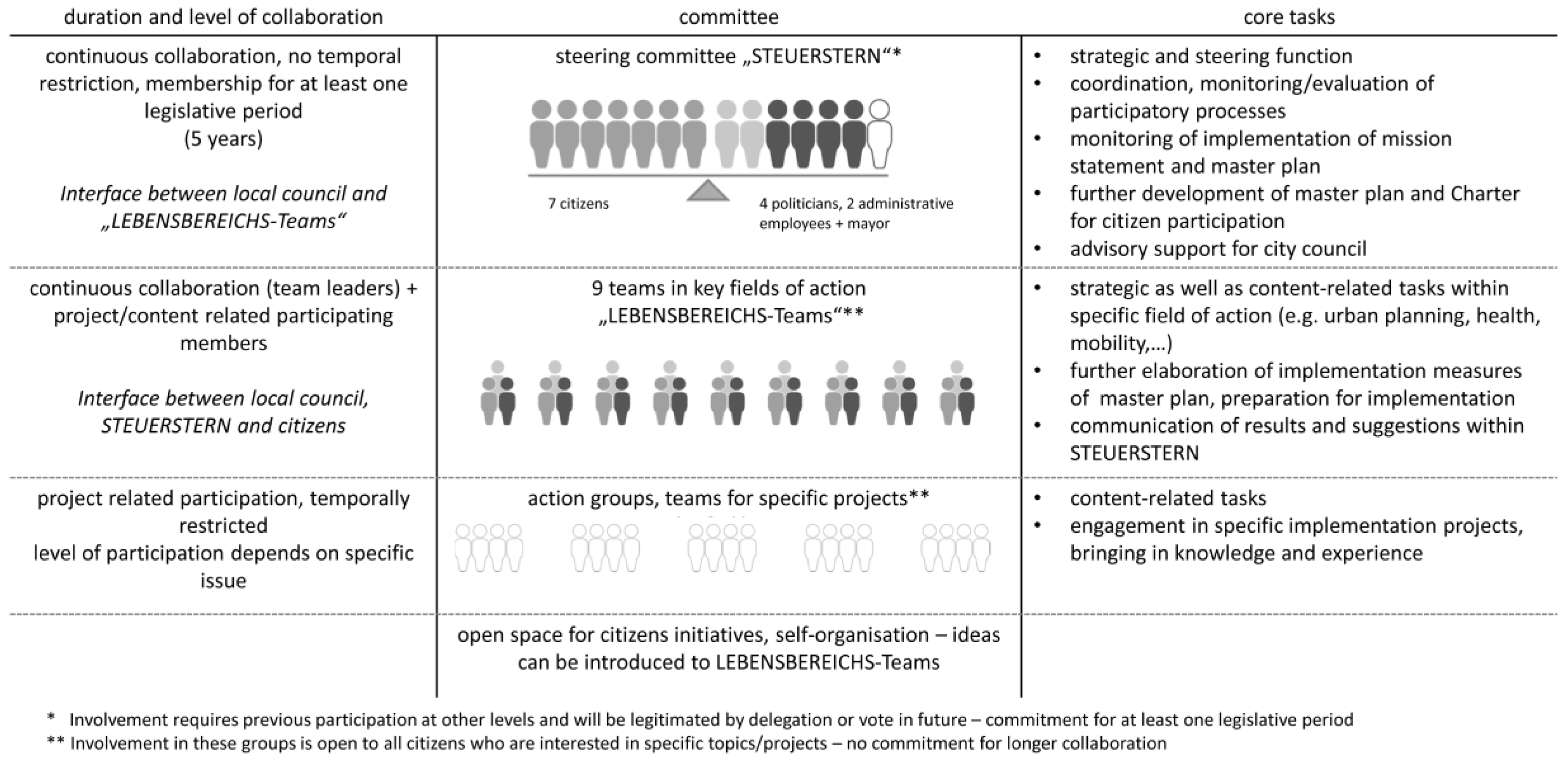

After completing the master plan at the end of 2015, the city’s membership within the urban renewal programme expired. Therefore, in phase 2 a Charter for citizen participation was elaborated on to ensure long-term collaboration between citizens and the government, as agreed on in the Leitbild. With this Charter, the urban government committed itself to a regulatory framework for long-term urban co-management between the city and its citizens. Centrepiece of the Charter was a follow-up group of the steering committee that supervised the implementation of the master plan and the mission statement as well as long-term citizen participation. The so called “Steuerstern” unites the steering committee from phase 1 and 2 and the advisory board of the expiring urban renewal programme. Citizens and municipal actors were again equally represented in the committee (7 citizens among 14 members). The commitment of the local council to an ongoing cooperation with this committee paves the way for future urban co-management.

Figure 3 shows that besides this committee—which required membership for a certain period and asked for a high level of time commitment, cooperativeness, and certain openness to learning processes and innovation—low-threshold offers for citizen participation were also provided.

Besides the implementation of these various committees, the annual publication of a forward-looking project list built another core element of the Charter for citizen participation. With this list, the city council obligated itself to an early communication of projects, which were planned for implementation within the next year. It not only provided transparent information of upcoming city activities, but also revealed where citizen participation was considered as being helpful from the perspective of the city council. With the new Charter, and for the first time in the city’s history, citizens also had the right to claim for becoming involved in certain activities listed in the project list. The actual planning and supervision of participatory processes lay within the responsibility of the Steuerstern committee, which should guarantee early collaboration and joint problem and process definition.

4.4. Challenges and Boundaries in Terms of Participatory Practice

The case study shows that what had started as a more or less typical example of citizen participation (phase 1, case-related, clearly defined goals, and operational framework for participatory development of a mission statement), had developed its own dynamics and thus had come up against boarders of conventional participation projects. While designing long-term co-management structures, especially the institutionalization of the Steuerstern steering committee, some mayor questions arose, which were of high relevance but also bore high uncertainty. Core questions were related to the issue of legitimacy and transparency of the committee: (i) Who is in and out—membership criteria? (ii) How and why are members of the committee legitimated to represent citizens’ interests within this committee for a longer period? (iii) How to ensure continuity within the steering group on the one hand and to remain open for new members on the other hand? (iv) How to ensure transparency and clarity of decisions made? (v) How to handle the management of time resources in a responsible way—as most of the work of the citizens was done voluntarily and unsalaried, while representatives from the city administration or council members often did it during their working hours?

Summing up, Korneuburg is breaking new grounds when institutionalizing long-term citizen participation. Instead of traditional project-related participative procedures (e.g., for the planning of a specific park or a pedestrian zone), the Charter regulates the co-management of the city by collaborative strategic planning and decision-making processes and shared responsibility for the city between citizens and authorities. While findings from participation literature and practice help to define procedures of project-related involvement of citizens, they provide little help in how to design appropriate rules for long-term co-management within the steering committee, blurring the boundaries between government (i.e., the representative democratic system) and citizens. In order to discuss these questions, we turn to theories on collective action and the sustainable management of commons to seek for valuable input, as presented in the following section.

6. Discussion of the Institutions for Urban Co-Management

Sustainability and resilience of urban systems heavily depend on the ability of urban actors to interact, deliberate, and collaborate [

3,

5,

59], as well as to continuously adapt and transform their institutional structures [

5,

60]. While the project-related involvement of citizens into urban development can be considered as state-of-the-art, we claim that long-term and reliable—but also flexible and forward-thinking—collaboration between urban actors (citizens, politicians and municipal administration) is required, in order to build networks of adaptive capacity. Urban co-management for resilience is thus very much based on learning by doing and processes of “trial and error” [

47].

Based on experience of our case study, we examined how such co-management agreements can evolve to address weaknesses of traditional case-based participation procedures, pre-defined by governmental authorities. We summarise weaknesses of short-term participation processes, based on critical literature on Arnstein’s conceptualization of the ladder of participation [

20] and pose the question of whether Ostrom’s design principles for the management of the commons [

28,

52] can support the design of long-term co-management institutions. As our results rely on a single case study of a co-management agreement implemented quite recently, it is much too early to draw final conclusions. Only the future will show the long-term success or failure of the co-management Charter of Korneuburg. Furthermore, it would need insights from more cities to distinguish context-specific aspects such as agency and local communication culture from generalizable institutional patterns. Due to these limitations the following discussion can only provide very preliminary theses that have to be tested in future research.

It is not the intention of our research to consider the framework of participation as outdated or useless. Instead, the wealth of experiences had over the decades remains useful to provide insights for case-related cooperation between citizens and urban government, where responsibility and decisive power remain in the hands of governmental actors. However, the traditional conceptualization of participation provides little insight into how long-term co-management processes of the diverse actors can be organized at eye-level [

21,

22,

29,

32], and thus indicates untapped potential for building resilient cities based on a broad range of knowledge, ideas, and resources of citizens willing to share responsibility for their city. To this end, Ostrom’s design principles provided some orientation for designing long-term co-management agreements based on self-organization and shared responsibility. For our case study they helped us to reflect upon the collaboration of the last three years and to find reference points for future institutional development. Especially the design principles 1, 3, 4, 6 and 7 (social boundaries, collective-choice arrangements, monitoring, conflict-resolution, and minimum recognition of rights) were confirmed by our case study as highly relevant, despite the lack of attention they gained in traditional participation literature. A main future challenge in developing the Korneuburg Charter of citizen participation will be to define procedures to balance the requirements of legitimacy and continuity on the one hand and flexibility and openness on the other hand (social boundaries), and to create low cost conflict resolution mechanisms (6). Nested organizations (8)—i.e., mainly the extension of the learning and collaboration process beyond Korneubug’s boundaries to other cities—also deserve attention. Less clear is the picture regarding the need for personal gains (2) and sanctions (5).

Ostrom’s design principles focus first and foremost on self-organized communities of users, and consider governments and formal regulations as external, contextual factors. Therefore, Ostrom’s design principles can only provide limited help in re-designing the power-relations between society and government. In contrast, Arnstein focuses on governments delegating power to citizens. The city of Korneuburg, however, searches for ways to manage eye-level collaboration at the interface between governance actors and self-organized citizens. As Boonstra and Boelens [

15] point out, new paths’ in participation—as those Korneuburg and other cities are experimenting with—may help to bridge the perceived gap between government and citizens. A shift from mere “top down” or mere “bottom up” towards a “middle-ground” might be the way to enter collaborative arenas, where the advantages of each are realised through a commitment to seeking solutions in a social learning process, openness to new ideas, responsiveness and pragmatism, as well as equity and diversity among horizontal and vertical links [

29].

The Korneuburg case also nicely illustrates the evolutionary character of institutions of urban co-management. Thus, the monitoring, evaluation, and further development of collaboration rules themselves should be given major attention in future research, as it “might be desirable to have institutions that are not persistent but may change as social and ecological variables change” [

61]. Institutions should therefore be “designed to allow for adaption because some current understanding is likely to be wrong […]. Fixed rules are likely to fail because they place too much confidence in the current state of knowledge” [

57]. Therefore, we also caution against panaceas. Each city will have to create institutions for urban co-management that root in past conventions of local collaboration, and consider experiences from elsewhere as the design principles or co-management institutions from other cities that are continuously tested, monitored, and adapted in a continuous evolutionary process. In the words of Berkes [

47], getting to co-management is “a long voyage on a bumpy road” and it “emerges out of extensive deliberation and negotiation, and the actual arrangement itself evolves over time”.

7. Conclusions

Referring back to social resilience, creativity, and self-organization, these elements can enable the capability of an urban system to re-organize and adapt to newly emerging challenges and circumstances. Therefore, developing self-organizing and flexible urban governance institutions is a crucial success factor for urban resilience building. The case study of Korneuburg highlights that building institutions for urban co-management requires thinking outside the box of pre-configured, case-related liaisons of power distribution between urban actors towards more continuous and reliable relationships at eye-level. The design principles can support the building of stable, albeit flexible, co-management structures to co-create trust and knowledge in long-term social learning experiences, to encourage creativity and experimentation by drawing on diverse resources and ideas, to facilitate multiple perspectives on preferred future development, and to trigger cultural change by negotiating new ways of decision making and opening the scope for active and self-organized citizens.

The case study showed that resilience building is much about innovation and experimentation and may be achieved only through evolutionary processes, involving various actors and integrating different types of knowledge. The existence of open learning arenas, self-organizing co-management structures and the scope for trustful collaboration and knowledge integration in an urban governance system can therefore be considered as key assessment criteria for urban resilience. Future urban research may have to focus more on transdisciplinary approaches in order to grasp the complexity of biophysical challenges, but also allow for meaningful social learning processes and the co-development of sustainable and future-oriented urban solutions.